From the beginning of the American republic, some Founding Fathers pushed for the establishment of an institution they thought crucial to the success of democracy: public education.

Self-government would require informed citizens, they felt. Important decisions would be in the hands of farmers and tradesmen, not courts and kings.

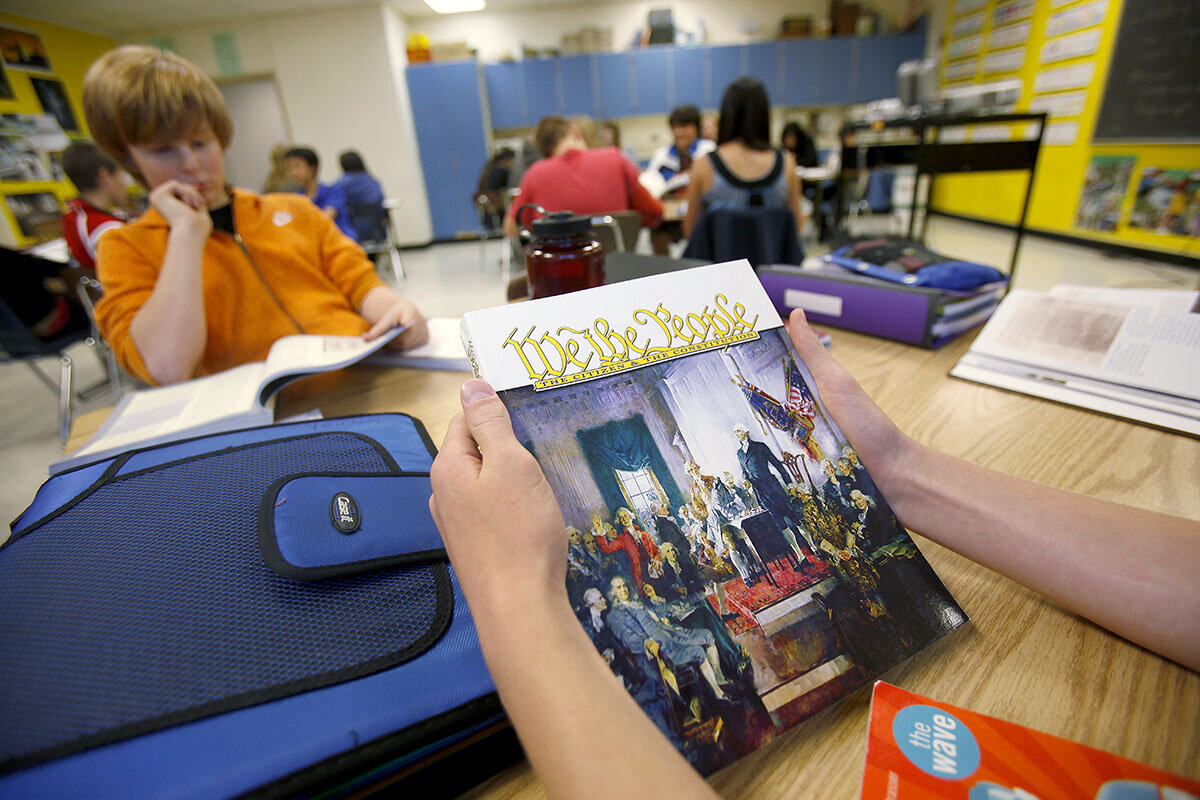

That meant the nation’s youth – the citizens of tomorrow – needed to learn the history and operation of republics. They needed practice disagreeing, debating, and then moving forward together, whether their views won or lost.

The “prospect of [a] permanent union” depended on education in the science of government, said George Washington. “The whole people must take upon themselves the education of the whole people,” said John Adams. “Above all things ... the education of the common people [should] be attended to,” said Thomas Jefferson.

Do today’s Americans agree on the importance of common schoolhouses? Do they hold anymore that public education is fundamental to U.S. democracy?

Many say they do. Polls show a majority of citizens generally give high marks to their local public schools and teachers. The vast majority of American children attend public schools for primary and secondary education.

But the pandemic years have been tough on public schools. Remote learning and physical isolation have taken a toll on test scores and driven many students out of the system altogether. The inequality in outcomes between rich and poor school districts has gotten worse.

Meanwhile, the nation’s political culture wars have elbowed their way into the classroom, as parents and administrators argue over issues dealing with gender, race, and basic U.S. history. The sort of civics education that directly teaches democratic principles and practice is getting squeezed out as curricula focus on preparing students for jobs and college.

The nation’s public schools are at a “turning point,” says Carl Hermanns, clinical associate professor at Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, Arizona State University, and co-editor of the book “Public Education: Defending a Cornerstone of American Democracy.”

Their status quo has been upended. They can seize the opportunity to improve and reinvent themselves. Or it is possible that the public education system may not survive in its present form.

“If it atomizes and ... public schools as we know them don’t exist anymore, what will happen is an open question,” says Professor Hermanns.

“One of the two foundational elements”

Citizens could certainly participate in democracy without public education. But public schools in the United States remain the foundation of the education of all but perhaps 13% of the student population, who attend private school or are home-schooled. And study after study has shown that the more education people have, the more they vote, and the more they participate in a nation’s political life.

There are some indications that year by year, education simply increases the general feeling that voting is a social and civic norm, the right thing to do.

“American public education is one of the two foundational elements of our democracy. The other is the ballot itself,” says Derek W. Black, a professor at the University of South Carolina School of Law and author of “Schoolhouse Burning: Public Education and the Assault on American Democracy.”

At the time of the American Revolution, elites remained nervous about opening up participation in choosing leaders to the common people, fearful that their participation would lead to mob rule and the rise of hucksters.

To many of the founders, schooling was the answer. Intelligent exercise of the franchise would hold democracy together.

“They believed that there was a common good, and that they’d find the common good together, through education,” says Professor Black.

That doesn’t mean public education was widespread in America from 1787 on. Despite the visions of Adams, Jefferson, and others, education in the early years of the nation was mostly limited to well-off white men – as was voting.

There are a lot of startup costs in the establishment of a school system, and many attempts to expand schooling foundered on the expense. In 1817, Jefferson proposed in his home state of Virginia to establish taxpayer-supported schools in every 5 or so square miles, teaching classical, European, and American history, as well as reading and arithmetic.

Jefferson’s effort did not pass. It took centuries for the vision of widespread public schools to be fully realized. Like voting rights, school rights grew step by step. At first limited to well-off white men, they expanded into lower incomes, other races, and women – sometimes sliding back, but by the civil rights era of the 1960s promised to all.

“You’ve got to have everybody educated from all walks of life in order for this [democracy] to work,” says William Mathis, senior policy adviser at the National Education Policy Center at the University of Colorado.

Shift from civics to job preparation

Civics education was an integral part of most public school curricula in the middle to later years of the 20th century. Teachers had the time and flexibility to dwell on more than just the basics of U.S. history and the structure of democratic government.

Yet the teaching of those subjects has “eroded” over the last 50 years, says the 2021 report from Educating for American Democracy (EAD), a diverse group of educators and scholars, partially funded by the U.S. Department of Education and the National Endowment for the Humanities, that is worried about this decline.

Across that same five-decade time period, partisan and philosophical polarization in the U.S. has increased, says the group. Social media and partisan news outlets have pumped dangerous amounts of political misinformation into the nation’s discourse. The public in essence may have lost the thread, with the majority functionally illiterate about our constitutional principles, according to the EAD report.

To this point, a 2017 survey by the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center found that only about 25% of Americans could correctly name all three branches of the U.S. government. One-third couldn’t name any branch of the government at all. Four years later, the Annenberg survey found that the number of Americans who could name all three branches had risen to 56%, and that 20% couldn’t name any branch at all.

“The relative neglect of civic education in the past half-century is one important cause of our civic and political dysfunction,” concludes the EAD report.

Why the slide in civics? Education experts say U.S. schools have been reoriented to focus on getting students ready to participate in the economy.

Thus, the rise of STEM – science, technology, engineering, and math – education. The Sputnik panic of 1957, when the nation was gripped by fear it was falling behind the Soviet Union in technical skills, has never completely abated. Studies still bemoan how U.S. children lag in math and science. Parents see STEM programs as gateways for better opportunity for their kids.

There is greater focus today on getting secondary students ready for college. Test-based educational reform has narrowed the focus of schools to narrower lesson plans focused on math and reading, lest their scores slide.

Amid all these pressures social studies, history, and other humanities topics have all become lower priorities. Government studies has often been de-emphasized.

“We have to remind ourselves over and over again that the whole point of compulsory free public education was to make citizens, was to produce people capable of self-government, and I think we forgot that because we talk [a lot about] the other two C’s ... career and college,” says Eric Liu, executive director of the Citizenship and American Identity Program at the Aspen Institute, and CEO and co-founder of Citizen University.

“Coming together in a shared space”

But public schools don’t just teach democratic habits through instruction, say their proponents. By their very design, American school systems are intended to model democracy, throwing together children from many walks of life in a single place for a common endeavor. They are supposed to learn people’s differences and other points of view.

“It’s a place where people from different backgrounds – and I mean everything from race and gender to religion and economics and general ideologies and different values – where people are all coming together in a shared space ... to see and value what it means to be an American,” says Sarah Stitzlein, professor of education at the University of Cincinnati and co-editor of the journal Democracy & Education.

But this communal aspect of public schools has faced challenges in recent years. To begin with, the pandemic too often physically isolated students, keeping them from the interactions that help them learn about each other. It drove down the overall number of students as well. About 1.3 million students have left public school systems since the pandemic began in 2020, according to one national survey. All but a handful of states have experienced enrollment declines over that period.

In addition, the culture wars have come for the schools, with state legislators and governors moving to control what can and can’t be taught about America’s racial history and sexism. Since January of last year, 42 states have introduced bills or taken other action that would circumscribe teaching on these sensitive subjects, according to a database maintained by Education Week. Seventeen of these states have imposed their bans.

This all takes place in the context of continued pressure from advocates of sweeping change in the way the nation educates its children to de-emphasize traditional public schools and greatly expand the use of charter and private schools.

Such radical decentralization would greatly affect the democracy-building mission of the public schools, say experts who support the traditional system. Among other things, it might expose students to less social and cultural diversity.

“I think the idea of ‘go find a better school that better matches your views to tone down the culture war’ is a huge danger to our society and to democracy,” says Dr. Hermanns.

But public schools really aren’t civic melting pots, say some right-leaning education analysts. They tend to be monolithic, segregated racially and socially, because they reflect the demographics of American communities.

And public schools are not alone in their ability to teach fundamentals of democratic involvement, says Michael Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute and co-editor of “How To Educate an American: The Conservative Vision for Tomorrow’s Schools.”

There’s evidence that private schools and charters “take their civic responsibility just as seriously as traditional public schools,” he says.

Needed: a shared conversation

More time devoted to teaching civics, social studies, and U.S. and world history. More emphasis on structured discussions and debate.

Those are the basic moves that scholars of democracy and education support to help strengthen schools’ role in developing citizens.

As to what specifically should be taught, there is far less consensus.

The bipartisan EAD effort does not lay out a specific curriculum. Instead it identifies categories that students should explore in discussions, from America’s role in the world in its history, to the nation’s social and institutional transformation over time, and the basics of civic participation.

“Fraught though the terrain is, America urgently needs a shared, national conversation about what is most important to teach in American history and civics, how to teach it, and above all, why,” says the EAD report.

One tool that might help students build their civic capacity is a sustained practice with meaningful disagreement in the classroom, says Ashley Berner, an associate professor and director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy.

Discussing controversial subjects is a learned skill, says Professor Berner. Teachers can foster an open climate for civil disagreement that does not threaten students’ identity.

“Civic tolerance is a learned behavior. We do not come by it naturally,” she says.

Professor Berner also favors pluralist educational systems, in which government funds a wide variety of schools, including religious schools, but maintains control over teaching standards, curriculum, and assessments.

Such systems “are common in democracies around the world,” she says.

In the United States, education is not a federal right. Such a right is enshrined in all 50 state constitutions, but not in the U.S. Constitution.

The nation should consider establishing such a right through the courts, Congress, or a constitutional amendment, says Kimberly Robinson, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law and editor of “A Federal Right to Education: Fundamental Questions for Our Democracy.”

America really has two educational systems, says Professor Robinson: one for upper- and middle-class students that works well, and one for low-income, rural, and many Black and Hispanic students that works much less well.

A federal right could provide leverage and attention to begin to counter that disparity.

“It’s important,” says Professor Robinson, “because the more educated a child is, the more likely they are to vote when they become an adult, and they are more likely to be engaged civically not just in elections, but in community service and other avenues and opportunities that help make our communities and our democracy stronger.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to include the most recent survey findings from the Annenberg Public Policy Center, and to clarify that the percentage of Americans attending public schools refers to the student population, rather than the entire population.

This story is the first in a four-part series:

Part 1: Do Americans agree on the importance of common schoolhouses? Do they still hold that public education is fundamental to democracy?

Part 2: How should schools teach children what it means to be an American?

Part 4: How has parental participation in public schools shaped U.S. education?