- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Gun rights: Supreme Court brings Second Amendment to the streets

- For Russian public, how full a view of war do front-line reporters give?

- Citizen building: What’s the best way to help students soar in a democracy?

- Can you be feminist and ‘pro-life’? The women who say yes.

- ‘Heal everybody’: Rapper Kendrick Lamar as caretaker of culture

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How we talk about tough issues

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

From start to finish, today’s issue of The Christian Science Monitor Daily has some very meaty things to chew on: the Supreme Court’s major ruling on gun laws, how Russians see their war in Ukraine, education’s role in democracy, and abortion. For many Americans, these issues are about more than policy. They speak to the course of the nation and personal well-being.

The tendency can therefore be to cast such issues in stark, almost apocalyptic terms. That’s understandable. These are difficult, visceral issues. But a recent article in Vox offers something more to consider. It looks at how societies talk about climate change and what effect that has on children. The article cites a 2021 study, which finds that more than half those polled between ages 16 and 25 said climate change had “doomed” humanity. The article states: “Some ‘climate anxiety’ is the product of telling kids – falsely – that they have no future.”

The author concludes: “I have yet to find a children’s book that frames the climate crisis … as a challenge, but one like the many that humanity has overcome, and one that our kids can overcome by learning about the world and inventing new solutions.”

That conclusion seems relevant to more than just children and climate change. What are the stories we are telling ourselves as adults – about abortion or gun laws? Our article on abortion today highlights someone who rejects stereotypes and urges collaboration across different viewpoints. Her perseverance and respect are some of our most powerful tools in addressing abortion – or any intractable issue. And they make for a very different kind of story.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Gun rights: Supreme Court brings Second Amendment to the streets

The Supreme Court’s ruling Thursday underscores just how dramatically judicial interpretation of the Second Amendment has shifted in recent decades.

-

Patrik Jonsson Staff writer

-

Harry Bruinius Staff writer

In its biggest Second Amendment decision in over a decade, the Supreme Court today said that Americans have a right to carry a handgun in public.

Today’s 6-3 ruling continues a throughline toward prioritizing Second Amendment rights for individuals. About half of U.S. states have adopted permitless or “constitutional carry,” and Americans purchased a record number of guns – 23 million – in 2020 during the pandemic.

The country has continued to wrestle with how to reduce gun deaths, which also reached a record high in 2020, at a time when firearms have proliferated and the Second Amendment has become a top priority among conservatives. The ruling comes the same week that the first gun safety bill in roughly 25 years is making its way through the Senate with bipartisan support.

“Anybody who says they’re surprised hasn’t been keeping up,” says Michael Lawlor, a criminal justice professor who co-sponsored the nation’s first red flag law in Connecticut in 1999.

The ruling won’t impede progress on federal gun control measures, like the bipartisan bill, or all state efforts to limit where guns can be carried and by whom, he believes. Those policies are now, in his view, arguably more urgent.

Gun rights: Supreme Court brings Second Amendment to the streets

In its biggest Second Amendment ruling in over a decade, the U.S. Supreme Court today said that Americans have a right to carry a handgun in public.

As it enters the final week of a controversial term – the court is expected to push federal law to the right in a number of areas, including abortion and climate regulation – the ruling in this closely watched case significantly expands gun rights. Delivered along the high court’s ideological divide, the decision also comes a month after a mass shooting at a Texas elementary school left 21 people, including 19 children, dead – a fact not lost on the dissenting justices.

Today’s ruling continues a throughline in America toward prioritizing Second Amendment rights for individuals. Half of U.S. states have adopted permitless carry or constitutional carry, which offers few, if any, restrictions on purchasing or carrying a handgun. Americans purchased a record number of guns – 23 million – in 2020 during the pandemic. There are an estimated 400 million guns in a country of 332 million people, or 120 guns per 100 residents.

The country has continued to wrestle with how to reduce gun deaths, which also reached a record high in 2020, at a time when firearms have proliferated and the Second Amendment has become a top priority among conservatives. The ruling comes the same week that the first gun safety bill in roughly 25 years is making its way through the Senate with bipartisan support.

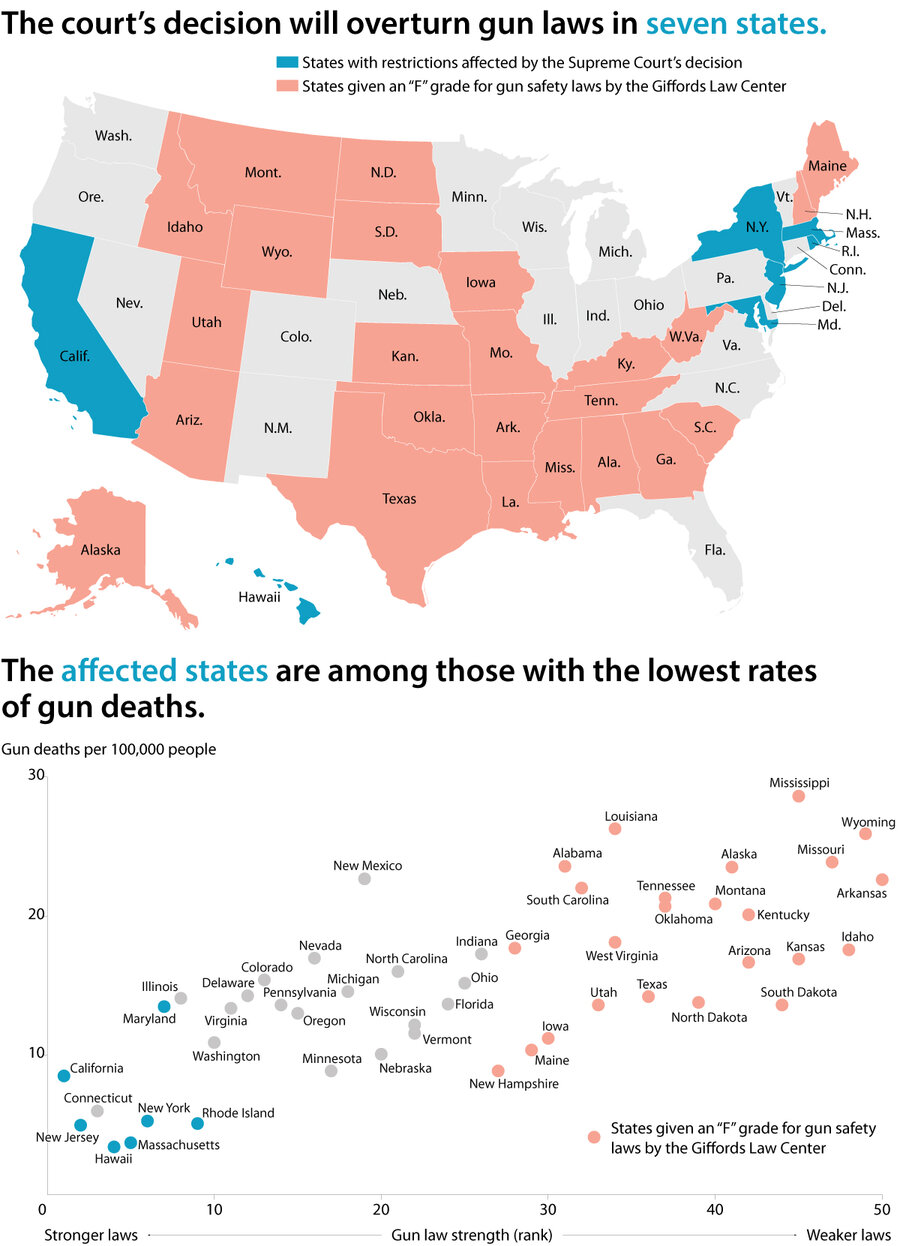

The 6-3 ruling in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen strikes down a New York regulation requiring individuals to have “proper cause” to carry a handgun outside the home. State licensing officials decided what qualifies as proper cause. Six other states have similar rules, which the court said today do not pass constitutional muster.

“We now hold, consistent with Heller and McDonald, that the Second and Fourteenth Amendments protect an individual’s right to carry a handgun for self-defense outside the home,” wrote Justice Clarence Thomas in the court’s majority opinion, citing the court’s two most recent gun cases.

Those decisions – District of Columbia v. Heller in 2008, and McDonald v. Chicago in 2010 – established an individual right to keep a handgun in the home, and applied that right to state and local laws, respectively. Today’s decision extends that right further, albeit with some restrictions that the court specifically outlines.

The outcome was not a surprise to watchers of the court and its conservative supermajority.

“Anybody who says they’re surprised hasn’t been keeping up,” says Michael Lawlor, a criminal justice professor at the University of New Haven, who co-sponsored the nation’s first red flag law in Connecticut in 1999.

He does add, however, that “the ruling makes a point to say that states can have reasonable rules, including limiting firearms in sensitive places like schools, airports, and things like that.”

The ruling won’t impede action on federal gun control measures like the bipartisan bill, or all state efforts to limit who can carry guns and where, he believes. But those kinds of policies are now, in his view, arguably more urgent.

“The country at the moment is flooded with guns,” he says. “There are way more guns in circulation than there are responsible gun owners. The goal of public policy should be to narrow that gap.”

In 2020, there were a record 45,222 gun-related deaths in the United States, according to the Pew Research Center. Of these, 54% were suicides and 43% were murders. Per capita, this represents 13.6 gun deaths per 100,000 people – still less than the peak number of 16.3 gun deaths per 100,000 people in 1974.

In a concurrence to today’s ruling, Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice Roberts specified that it only applies to the gun restrictions in six states with laws similar to New York’s. Those happen to include the states with the nation’s lowest rates of gun deaths: Massachusetts, with 3.7 deaths per 100,000 people; and Hawaii, with 3.4, as well as Rhode Island, New Jersey, and California, plus the District of Columbia.

Giffords Law Center

New York has long had one of the lowest rates of gun fatalities in the nation, with a rate of 5.3 gun-related deaths in 2020. The state with the highest rate was Mississippi, with 28.6 deaths per 100,000 people, followed by Louisiana (26.3) and Wyoming (25.9).

History’s role going forward

In 2008, the Supreme Court significantly changed its interpretation of the Second Amendment. In the 5-4 ruling in Heller, the majority determined for the first time that the Constitution protects an individual right to keep a handgun in the home. The decision provoked a torrent of unanswered questions, including how governments can regulate firearm ownership. In scrutinizing those policies in the years since, lower courts have coalesced around a two-step framework combining historical analysis with a determination of whether a policy achieves a compelling or important government interest.

Today’s ruling cuts that framework in half.

“Despite the popularity of this two-step approach, it is one step too many,” wrote Justice Thomas.

“Only if a firearm regulation is consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition may a court conclude that the individual’s conduct falls outside the Second Amendment’s ‘unqualified command,’” he added.

While the decision is relatively limited, in terms of seven states being immediately affected, the shift in how courts must now interpret gun policies is hard to overstate, says Joseph Blocher, co-director of the Center for Firearms Law at Duke University Law School in Durham, North Carolina.

“Substantively the case is relatively narrow, but methodologically it is enormously broad,” he says.

Deciding Second Amendment cases purely on the basis of history and tradition is “going to involve a whole lot of judicial intuition and discretion and lack of transparency,” he adds.

“Now lower courts have to evaluate whether a city or state can prohibit guns in a day care center, for which there is no rich historical record,” he continues. “We’re in for a lot of open questions on what is constitutional.”

The majority does state that there are limits on the right to bear arms. It is “settled,” for example, that people can’t carry firearms in “sensitive places” like courthouses and polling places, wrote Justice Thomas.

Courts can determine “new and analogous sensitive places are constitutionally permissible” based on history, he continued. But expanding the definition of sensitive places “to all places of public congregation that are not isolated from law enforcement defines the category of ‘sensitive places’ far too broadly.”

In his dissent, Justice Stephen Breyer – joined by the two other members of the court’s liberal wing – highlighted the questions that interpretive method leaves unanswered. “Where does that leave the many locations in a modern city with no obvious 18th- or 19th-century analogue? What about subways, nightclubs, movie theaters, and sports stadiums?” he asked. “The Court does not say.”

“As technological progress pushes our society ever further beyond the bounds of the Framers’ imaginations, attempts at ‘analogical reasoning’ will become increasingly tortured,” he continued.

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Bruen underscores just how dramatically Second Amendment jurisprudence has shifted in recent decades.

“When I started writing about this stuff in the ’90s, you were laughed at for making the argument that the Second Amendment is the right of an individual to own a firearm,” says Glenn Reynolds, a professor at the University of Tennessee College of Law.

“Now conventional wisdom has turned around to the point where [that individual right] commands two-thirds of the Supreme Court,” he adds. “I always tell my students, it is amazing how much power the force of ideas have in the world.”

What next for gun control debate

The Bruen decision has arrived as America’s gun control debate has reached a particularly heated moment. As Congress moves closer to passing the first package of federal gun regulations in a quarter century, the nation is still processing recent mass shootings in Uvalde, Texas; and Buffalo, New York, the latter of which killed 10 people.

Justice Breyer opened his dissent by noting that 45,222 Americans were killed by firearms in 2020, and that gun violence “has now surpassed motor vehicle crashes as the leading cause of death among children and adolescents.” Later, he listed nine high-profile mass shootings from the past 10 years.

Some of his colleagues downplayed or dismissed that statistical and anecdotal context.

In a footnote, Justice Thomas responded with a quote from the 2010 McDonald opinion that the right to bear arms “is not the only constitutional right that has controversial public safety implications.”

In a separate concurrence, Justice Samuel Alito questioned the relevance of statistics on mass shooting events, suicides by firearms, and the use of guns in domestic disputes. The New York law at issue “obviously did not stop that perpetrator” of the Buffalo shooting, he wrote. “There can be little doubt that many muggers and rapists are armed and are undeterred” by the New York law, he added.

The link between gun control policies, or the lack thereof, and gun violence is tenuous. But the states that will likely be directly affected are also those with some of the country’s lowest rates of gun deaths.

This context was at the forefront of criticism of the Bruen opinion today. President Joe Biden said in a statement that he was “deeply disappointed” in the ruling.

The decision “contradicts both common sense and the Constitution, and should deeply trouble us all,” he added. “In the wake of the horrific attacks in Buffalo and Uvalde, as well as the daily acts of gun violence that do not make national headlines, we must do more as a society – not less – to protect our fellow Americans.”

In his own statement, New York Mayor Eric Adams promised to do just that.

With steps including a review of how the city defines “sensitive locations,” he said New York “will work together to mitigate the risks this decision will create once it is implemented.”

The Bruen decision “may have opened an additional river feeding the sea of gun violence, but we will do everything we can to dam it,” he added. “We cannot allow New York to become the Wild West.”

The reaction from New York so far seems to preview where the gun policy debate will now move.

The Bruen ruling today “is going to force, very much against their will, states that have discretionary issue like New York to change their ways,” says Professor Reynolds. “I expect there will be a campaign of massive resistance to that, which will probably require further enforcement” from the Supreme Court.

However it unfolds from here, more than a decade since its last examination of the Second Amendment, the Supreme Court has once again transformed the debate over American gun policies.

“It’s a monumental decision,” says Richard Aborn, president of the Citizens Crime Commission of New York City.

“It’s the first time in the history of the United States that a court has ruled that there’s an individual right to carry a concealed firearm,” he adds. “It doesn’t get much bigger than that.”

Editor's note: This story was updated to correct the name of the University of New Haven.

Giffords Law Center

For Russian public, how full a view of war do front-line reporters give?

Russia’s war correspondents are shaping their nation’s view of the Ukraine invasion. The story they are telling is not rose-colored, but is it trustworthy?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

To understand the events of the war in Ukraine, the Russian public relies on dozens of reporters who have been embedded with the armies of Russia and its separatist allies.

These embeds – who travel with Russian forces, follow military guidelines, and appear to fully support the Russian cause – offer millions of Russians their observations, assertions, and basic narratives in detailed and graphic daily reports. Opinion polls suggest that majorities of Russians increasingly trust these reports.

That doesn’t mean sanitizing the reporting. Leading war correspondent Alexander Sladkov, who intensively covered Russia’s devastating two-month siege of the Donbas port city Mariupol, spared his viewers none of the horrific destruction and gruesome scenes of a city in flames amid brutal street-by-street combat.

Anatoly Tsyganok, an independent military expert, says the aggregate work of Russian war journalists sheds a lot of light on the nature of the conflict. “You can’t get a full picture of what is really happening if you exclude what is being reported by one of the sides,” he says. “I get my information from every possible direction, and I can say that Russian correspondents ... are as professional as any in the West.”

For Russian public, how full a view of war do front-line reporters give?

Alexander Sladkov has been covering military conflicts for Russia’s main state TV channel for three decades. The burly, bearded, motorcycle-riding ex-military officer is considered by many to be Russia’s top war correspondent.

Now, he’s one of dozens of reporters, including several women, who have been embedded with the armies of Russia and its Donbas separatist allies to report on Russia’s war in Ukraine over the past four months.

Millions of Russians see the conflict, often in detailed and graphic daily reports, through the observations, assertions, and basic narratives formed by these reporters who travel with Russian forces, follow military guidelines, and appear to fully support the Russian cause. Opinion polls suggest that majorities of Russians increasingly trust these reports.

While a handful of independent Russian journalists, such as Meduza’s Lilya Yapparova, have produced some compelling alternative coverage by striking out on their own in Ukraine, the Russian reporters mostly offer a view of the war at odds with that of their Western counterparts. But their coverage is nonetheless more than simple propaganda; it reflects a combination of journalistic methods and a Russian understanding of the world.

“Everyone knows that I’m a person who wouldn’t report anything that I’m not 100% certain of,” Mr. Sladkov says. “I am not an information warrior – I know that there are lots of such people – but I am a reporter. These days I get a lot of time [on the premier Channel One news program] because interest is very high. Nobody tells me what to report.”

“No need to explain ... what war is”

Mr. Sladkov, who intensively covered the devastating two-month siege of Mariupol, a Donbas port city on the Azov Sea that was defended by Ukrainian forces for the past eight years, spared his viewers – and the subscribers to his Telegram channel – none of the horrific destruction and gruesome scenes of a city in flames amid brutal street-by-street combat. He actually went out of his way to show the forests of sad, temporary graves of civilians caught in the crossfire that sprang up in apartment courtyards amid the smoke and relentless gunfire.

He says it’s not surprising that Russian audiences can look at all that horror without flinching, much less questioning their state’s purpose. “Russia has been constantly at war for decades. There is no need to explain to society what war is,” he says. “Every schoolboy can tell you the difference between a tank and an APC [armored personnel carrier], and identify all different sorts of weapons and what they are for.”

There was the Soviet war in Afghanistan in the 1980s, two devastating wars in the separatist Russian region of Chechnya, a brief but bloody conflict with Georgia in 2008, a highly kinetic Russian intervention in Syria since 2015, and an ongoing war against Kyiv in the Donbas for the past eight years, which the Russians claim the present “military operation” is designed to bring to a victorious end.

Mr. Sladkov has covered most of those wars. He was also embedded with United States infantry in Afghanistan and Iraq, where he says he learned much of what he knows about his trade.

Though he served 10 years in the Soviet army, he insists that he is not a soldier. And he says that his relations with the military are often “complicated” regarding where he can go and what he can report. “Of course there are military secrets, and you do need to keep a balance. If I have a weakness, it’s that I probably haven’t looked hard enough at the people, the civil population, who are trapped in the middle of the war. It’s not just about the troops.”

A supportive public

Though embedded journalists like Mr. Sladkov and Alexander Kots, another leading war correspondent interviewed for this story, enjoy massive advantages in terms of access to the troops and the front lines, as well as mega-audiences at home, nobody denies that the format is restrictive.

“Our war correspondents work according to the rules of wartime, and they must know how to behave on the battlefield,” says Viktor Baranets, a former official Russian military spokesman who is now the military columnist for the Moscow daily Komsomolskaya Pravda. “The journalist must accept the rules, and never deviate from them. A battlefield is not a playground.”

Mr. Baranets adds: “Personally, I think the Russian public gets more information than it should. As for casualties, I would never declassify this data before the operation ends. Why give the enemy the pleasure of hearing about our losses? We can square everything when it’s over.”

The improving levels of trust in the Kremlin’s decisions, engendered by official war reporting, seem reflected in recent public opinion surveys. A poll published this month by the state-funded Public Opinion Foundation found that 78% of Russians express confidence in President Vladimir Putin, reversing a prewar slide in his standing, while 85% identified themselves as “patriots.”

Another June poll, by the independent Levada Center, found that majorities of Russians pay close attention to events in Ukraine, and growing numbers are turning to state TV for their primary news about the conflict. A study by the internet research firm Mediascope supports that. The Levada poll found that 53% of respondents believe that TV coverage of the war is “objective.” Only a third said they rely on internet sources for their information about the war.

“I didn’t set out to report on war crimes”

There are things that embedded Russian correspondents don’t do: providing information about casualties, or graphically showing Russian losses. Neither will they finger Russian service members for crimes, whether looting, corruption, rape, or murder. Mr. Sladkov defends the record of the Russian military for punishing its own criminals – he cites the case of Yuri Budanov, a Russian officer convicted of murdering a Chechen woman during the first Chechen war – but insists it’s up to courts, not himself, to make such judgments.

When Russian troops were accused of war crimes in the Ukrainian city of Bucha in April, Mr. Kots, who had been there at the time of the Russian withdrawal, went public to say that he saw no bodies in the streets. He suggested that Ukrainian punitive squads who entered later actually did the killing. Though evidence impugning Russian troops has mounted since, he still stands by his claim.

Ms. Yapparova, a war correspondent with the Latvia-based opposition outlet Meduza, has a different perspective. She says she went to Bucha following the Russian withdrawal with no intention other than to find out what happened.

“It seemed to me that the priority should be [to document] the human suffering,” she says. “There might be a lot of unclear situations, facts that need to be established, but it was quite obvious what was happening, and who the aggressor is. I didn’t set out to report on war crimes committed by my own country’s army. I just turned on my tape recorder and that’s what I found myself doing. I was doing my job.”

Journalists and patriots

Anatoly Tsyganok, an independent military expert, says it’s a pity that Western countries have mostly banned or curtailed Russian-sourced reportage from reaching their own populations. There is no doubt that the aggregate work of Russian war journalists sheds a lot of light on the nature of the conflict, including the Russian conviction that it is a war to liberate the Russian-speaking people of the Donbas from Ukrainian nationalist oppression, he says.

In the battle of Mariupol as described by Russian war correspondents, it was mainly the forces of the Donetsk People’s Republic who fought their way through the city, which they consider their own territory. Their main opponent was the notorious Azov Regiment, who set up their fighting positions in homes and schools, leading to their destruction. In Russian reportage, the surviving civilian population emerged to express gratitude for their liberation. The degree of truth in this narrative may only be determined by historians, but it’s what most Russians today appear to believe.

“You can’t get a full picture of what is really happening if you exclude what is being reported by one of the sides,” says Mr. Tsyganok. “I get my information from every possible direction, and I can say that Russian correspondents, like Sladkov, are as professional as any in the West.”

Somewhat ominously, Mr. Sladkov and Mr. Kots believe that Russia is locked in an existential struggle against the entire West, not just the pro-Western regime in Kyiv, and both think the war will be long and hard, lasting at least five years.

“I am a patriot of my country, and I understand that there is no choice but to go forward to victory,” says Mr. Kots.

Ms. Yapparova, the independent journalist, says she doesn’t approve of her embedded colleagues. “Sladkov works for a huge, wealthy propaganda machine. I’m just a journalist.” But she does have one essential point of agreement with him. “I still consider Russia to be a great country. And I am a patriot of Russia.”

A deeper look

Citizen building: What’s the best way to help students soar in a democracy?

Are we better off as a nation investing in a system where talented students can soar, or one in which everyone is educated equally? Can’t we have both? Boston offers a case study. Part 3 in a series.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

-

By Kelly Field Contributor

A fight in Boston over the future of training gifted students is at once an intensely local dispute, and part of a broader national debate about meritocracy and access to public education.

That debate, which goes back decades, centers on what most strengthens the social, political, and economic fabric of a democratic nation. Is it an education system that sorts students by academic ability – often giving top students more resources and the opportunity to move ahead quickly – or one in which classrooms embrace all students in the expectation that equal access will drive a much broader number of kids higher and widen opportunity?

The gifted program in Boston is a lifesaver that ought to be expanded, so more students like hers can benefit, says parent Cathy Ware.

But some critics argue that children from Black, Latino, and Indigenous communities are underrepresented in accelerated offerings. Also, sorting high-achieving students into separate classrooms is a “total mismatch” for today’s global knowledge economy, says Michael Horn, an adviser on the future of education. He suggests that the best approach is to tailor instruction to individual students – via technology, for example.

“We ought to be keeping access to the ability to soar,” he says, “but putting a heck of a lot more resources and belief into the fact that many more can.”

Citizen building: What’s the best way to help students soar in a democracy?

When Cathy Ware’s son was in the third grade, he struggled to stay engaged and was frequently disruptive.

But when he tested into Boston’s gifted and talented program, known as Advanced Work Class, in the fourth grade, his behavior problems vanished. No longer bored, he loved school.

As Ms. Ware sees it, the decades-old program is a lifesaver that ought to be expanded, so more students can benefit from its challenging curricula.

“Kids who need to go farther, faster, that’s a special need, just like a kid who is having trouble reading,” she says.

But Edith Bazile, an education activist and former Boston Public Schools teacher, says AWC, which disproportionately enrolls white and Asian children, should be dismantled. She’s pushing district leaders to invest, instead, in Excellence for All, a newer competitor meant to bring rigorous coursework to whole classrooms of students, without entry test requirements.

In Ms. Bazile’s view, Advanced Work Class is blatantly inequitable, and the parents and teachers fighting to preserve it are “hoarding resources, instead of thinking about how to expand opportunity for everyone.”

The fight over the future of the two programs is at once an intensely local dispute, and part of a broader national debate about meritocracy and access to public education. That debate, which goes back to the birth of gifted education in the 19th century, centers on what most strengthens the social, political, and economic fabric of a democratic nation. Is it an education system that sorts students by academic ability – often giving top students more resources and the opportunity to move ahead quickly – or one in which classrooms embrace all students in the expectation that equal access will drive a much broader number of kids higher and widen opportunity?

For some, educators, it’s a false dichotomy.

“That tension has been around for years – the trade-off between excellence and equity,” says James Borland, a professor of education at Columbia University’s Teachers College. “I don’t think we need to choose between them.”

The debate in Boston over how to support younger students comes as elite exam high schools on both coasts are rethinking their reliance on grades and test scores in admissions decisions. Some schools have changed their entrance criteria, aiming to expand access to more Black and Latino students. But those schools have faced pushback – and lawsuits – from some parents and alumni, who say the changes discriminate against Asian Americans and undermine the notion of merit.

And Boston is not the only city wrestling with what to do about gifted education in the early grades. In New York City last year, outgoing mayor Bill de Blasio announced a plan to phase out gifted education for elementary schoolers in favor of “accelerated” learning for all students. His successor, Eric Adams, opted to expand the gifted and talented program instead.

When gifted classrooms and schools were created in the late 1800s, they were seen as a way to ensure that the nation’s most promising students reached their full potential. Subsequent studies have found that for some students, the programs have done just that.

Yet the approach has long been criticized for underrepresenting talented Black, Latino, and Indigenous students and increasing segregation in the nation’s public schools. Some say the programs take resources away from needier students.

Michael Horn, an author and adviser on the future of education, says sorting high-achieving students into separate classrooms might have worked in the past, when Americans didn’t need a college credential to earn a living wage. But it’s a “total mismatch” for today’s global knowledge economy, in which all students need to be educated to a higher level to succeed.

The solution, Mr. Horn says, lies in training teachers to better tailor their instruction to individual students’ strengths and weaknesses – a common pedagogical practice known as “differentiation.”

But catering to kids with widely different abilities isn’t easy, especially in large classes with only one teacher. Often, parents of high-achieving children in regular classrooms worry that their kids are being overlooked by their overburdened teachers, who must focus their energy on students who are struggling.

“The students who get the least attention are the ones who are doing well,” says Ms. Ware, whose son was often told to read a book when he was done with his work.

Questions about equity

In a recent study of the Excellence for All program, which is in classrooms in grades four through six, teachers said they felt exhausted trying to “serve all students’ needs to the best of their ability.” Asked what could make the program more successful, they collectively responded: “more bodies in the classroom.”

More homogeneous “accelerated” classrooms, like the ones that Advanced Work Class creates for fourth through sixth graders, are easier for teachers to manage. Advanced students, like Ms. Ware’s son, can tackle complex texts and math problems, without having to wait for the rest of the class to catch up.

“It feels more like teaching high school English than a typical elementary class,” says Roxanne Saravelas, a longtime AWC teacher in the William Ohrenberger school in West Roxbury, a neighborhood in Boston. In the last full school year before the pandemic, her students showed levels of academic growth in English language arts that were well above school, district, and state averages, with Black and Latino students performing at the same level as their white peers, according to data she shared.

“This could be something that could help close the achievement gap, if it were targeted to children of color who are showing academic promise,” Ms. Saravelas says.

A recent review of Advanced Work Class found that it boosts high school graduation and college enrollment rates, particularly among Black and Latino students. That increase does not seem to be due to teacher quality – though accelerated classrooms often employ veteran teachers – or to the positive “peer effects” of being surrounded by high-ability peers. Rather, it seems that enrolling in Advanced Work Class sets students of color on a trajectory for success, making them more likely than similar students in regular classrooms to meet milestones like taking the SAT – and less likely to fall off the track to graduation in the 11th or 12th grade.

For years, though, Black and Latino kids have made up a minority of students enrolled in Advanced Work Class. During the 2020-2021 academic year, Black and Latino students accounted for close to three-quarters of students in Boston Public Schools, but just under a quarter of students in the fourth grade cohort of AWC.

“The supreme irony is that this program underrepresents the very group that the benefits are largest for,” says Sarah Cohodes, an associate professor of economics and education at Teachers College, and author of the study.

It was this glaring disproportionality that led a team of researchers commissioned by Boston Public Schools nearly a decade ago to recommend that the district convert all classrooms in grades four to six to Advanced Work Class “with high expectations and rigorous coursework” – and prompted then-Superintendent Tommy Chang to create Excellence for All to fulfill that goal.

Dr. Chang, who came to Boston from Los Angeles shortly after the researchers released their report in 2014, says he was shocked to discover that the district was still sorting students in elementary school. Most districts stopped “tracking” students into separate classrooms in the early grades decades ago, he says.

He recalls walking the halls of one elementary school early in his tenure and seeing an AWC class on one side of the hall, and the “regular” class on the other.

“It was very clear, it was separated by race, and unequal opportunities were being offered,” he says.

Excellence for All, which aims to improve instruction in writing and math – while expanding students’ access to enrichments like coding, robotics, and world languages – was created “to challenge the idea that we needed to give students a test and segregate them to get high rigor,” says Colin Rose, then an assistant superintendent in charge of reducing racial inequities in Boston Public Schools. “Advanced Work Class,” he adds, is “antithetical to the values we are promoting for equity.”

A consideration: student morale

Though Dr. Chang never formally proposed eliminating Advanced Work Class, rumors that he might alarmed parents like Prince Charles Alexander, who see the program as the surest route to Boston’s elite exam schools. Mr. Alexander, a recording and mixing engineer whose work has garnered Grammy Awards and nominations, credits much of his professional success to Boston Latin School, and he wanted his twins, now 10, to be ready to attend.

“When people tell you that you’re good, you feel good. When people tell you you’re doing well, you feel like you can do well,” says Mr. Alexander, who teaches at the Berklee College of Music. “My life has been colored by Boston Latin because I feel like I succeeded at something that was hard to do.”

His boy-girl twins, who were ultimately admitted to the Ohrenberger Advanced Work Class in the fourth grade, “understand that AWC is pulling them towards a certain excellence,” he says.

Still, Mr. Alexander, who is Black, recognizes that the affirmation his children get from Advanced Work Class has a flip side, and he’s troubled by the program’s racial imbalance.

“You’ve got the AWC kids saying ‘I got it going on,’ and you have the other kids saying ‘I don’t,’” he says. “That’s one of the problems of creating an elite class within a school with a large minority population, when the elite class is primarily nonminority.”

Julia Bott, the principal of the Ellis Mendell Elementary School in Roxbury, another Boston neighborhood, saw those dynamics at play in her own school before it joined Excellence for All. When children abandoned her school in fourth grade for a school offering Advanced Work Class, the remaining students would make comments about how the smart kids were leaving, she says.

“What does that do to a child when, in the fourth grade, they start to internalize beliefs about their intellectual capacity?” she says.

When the district rolled out Excellence for All in 2016, Ms. Bott jumped at the chance to join. A firm believer in inclusion, she’d done away with separate classes for students with disabilities, but found some teachers were struggling to target instruction in the upper elementary grades, when the gaps between students grew larger. Excellence for All aligned with her own values, and provided her teachers with training in writing instruction and math.

That first year, 13 schools joined Excellence for All, including three that switched from Advanced Work Class to do so. Today, there are 15 schools that offer Excellence for All, and four that offer Advanced Work Class, down from 22 in 2014.

When the pandemic hit, the district stopped administering the AWC entrance exam, allowing schools to choose between offering the program to all students, and letting students opt into it. Last summer, a working group on the program’s future recommended that the district permanently suspend testing into Advanced Work Class, but stopped short of calling for the program’s elimination. District leaders will bring their own recommendations and implementation plan to the school committee this fall, a spokesperson says.

In the meantime, a natural experiment in inclusion is playing out in the Ohrenberger school, where admission to Advanced Work Class has been open to all students for the past two years. Some of the fourth graders now in the program were recommended by teachers; others requested a spot.

Ms. Saravelas, one of two AWC teachers there, says it’s been more challenging teaching this year’s fourth graders than a typical cohort, though it’s hard to say how much of that is due to the disruptions of the pandemic.

“We are giving those kids who are raising their hands the opportunity to give it a try,” she says.

Meanwhile, Mr. Horn, the author, says both sides of the debate over gifted education are “missing an opportunity to create a model that personalizes for each student.”

He argues that new technologies, which allow children to work independently while teachers roam the classroom, checking on their progress and providing support, have made personalized learning easier than it used to be.

“We ought to be keeping access to the ability to soar,” he says, “but putting a heck of a lot more resources and belief into the fact that many more can.”

This story is the third in a four-part series:

Part 2: How should schools teach children what it means to be an American?

Part 3: Are we better off as a nation investing in a system where talented students can soar, or one in which everyone is educated equally? Can’t we have both?

Part 4: How has parental participation in public schools shaped U.S. education?

Can you be feminist and ‘pro-life’? The women who say yes.

The founder of New Wave Feminists breaks stereotypical labels, describing herself as a “pro-life” feminist. She’s also ready to cooperate with those who see things differently, as long as their collaboration promotes dignity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Destiny Herndon-De La Rosa, founder of the “pro-life” group New Wave Feminists, shows up for our Zoom interview in a black T-shirt reading “Dad Bod” falling off her shoulder. She fits the part of an organization that bills itself as “Badass. Prolife. Feminists.”

Yet the likelihood that the U.S. Supreme Court will send the debate about abortion back to the states doesn’t feel like a victory to her.

“Our work actually isn’t going to change one bit if Roe is overturned because our whole point is not necessarily in regards to legality. It’s about the reality women are facing,” she says. “I see leaders taking away options, but they’re not necessarily supplementing them with other options for women.”

If Roe is overturned, she says, it will split the country further between states that offer abortion sanctuary and those that pull “trigger laws” to effectively end it – with all the resources from the anti-abortion camp heading to the sanctuary states to fight abortion.

“The problem with that is there are still going to be pregnant women in states like Mississippi, Texas, or Louisiana. There’s women in those states who need housing, transportation, child care, and health care, especially in rural areas.”

Can you be feminist and ‘pro-life’? The women who say yes.

Destiny Herndon-De La Rosa, founder of the “pro-life” organization New Wave Feminists, would seem at the cusp of hard-won victory.

She’s a resident of Dallas, and in 2021 her state passed the so-called heartbeat bill, which essentially prohibits women in Texas from getting an abortion beyond six weeks of pregnancy – a law celebrated by the anti-abortion movement nationally.

Now, less than a year later, the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which is expected any day, could roll back the constitutional guarantee that allows women in all 50 states to seek abortions up to fetal viability.

But the activist says she doesn’t feel like the winner here. Even if the Dobbs decision returns the abortion debate back to the states – likely resulting in about half of them prohibiting or severely restricting the right – she says she sees it as a small battle won in a war she’s still losing.

“We’re not trying to defund Planned Parenthood. We’re not trying to overturn Roe. Our work actually isn’t going to change one bit if Roe is overturned because our whole point is not necessarily in regards to legality. It’s about the reality women are facing,” she says. “I see leaders taking away options, but they’re not necessarily supplementing them with other options for women.”

The anti-abortion and abortion-rights camps have been pitted against each other, perhaps like never before, as the Supreme Court decision nears. But the position of New Wave Feminists shows how complex the reproductive environment will become – with no clear winners and losers. At the same time, perhaps optimistically, some see hope that complexity may carve out space for cooperation to help all women, especially those who are most vulnerable.

Sparked by a billboard

We meet over Zoom, since I’m in Toronto and Ms. Herndon-De La Rosa is in Dallas. She shows up in a black T-shirt reading “Dad Bod” falling off her shoulder. She fits the part of an organization that bills itself as “Badass. Prolife. Feminists.”

We start with the term “pro-life feminism,” which many feminists scoff at. (In fact, when I wrote a cover story asking “Can you have women’s rights without abortion rights?” the vast majority answered with a resounding no.)

That doesn’t surprise her. New Wave Feminists was briefly a sponsor of the 2017 Women’s March on Washington until it was uninvited over its anti-abortion views. Yet Ms. Herndon-De La Rosa does sound like a feminist – one whose raison d’être isn’t just opposing abortion – as she rails against “the patriarchy.”

New Wave Feminists was formed on a fluke. Ms. Herndon-De La Rosa remembers driving down a Texas roadway with her 5-year-old son in the early 2000s when they passed a billboard advertising a restaurant, using women’s breasts in the form of chicken wings. “My feminist rage just went off,” she says. She and two friends penned a furious letter to the city council, signing off as “New Wave Feminists” to add gravitas. They scored their first victory: The offensive part was painted over.

Ms. Herndon-De La Rosa says she’s always been “pro-life.” She found herself pregnant at 16 and kept the baby.

With regard to New Wave Feminists, though, “the pro-life part came after the fact. And I debated it,” she says.

She finally included it as a main platform for the organization after realizing how little room the feminist movement gave to anti-abortion voices. “I knew it was going to be unpopular. I had no idea it was going to be quite so unpopular.”

Since then her views have evolved to advocate a “consistent life ethic,” a movement opposed to violence of any kind – from abortion to unjust war to capital punishment – that was popularized in the 1980s by the Roman Catholic Church.

I had never heard the term, so I looked it up and was struck by how its top issues sounded a lot like those of the reproductive justice movement, which I’d just reported on. In particular, the groups’ stances against police brutality and violent discrimination against vulnerable groups overlap. The main difference between them: One supports access to abortion and the other doesn’t, and that’s a gaping difference, especially for those who fall on the hard line of either spectrum.

Ms. Herndon-De La Rosa told me they work with a consistent life ethic group called Rehumanize International, which is based in Pittsburgh, where New Voices for Reproductive Justice, featured in my earlier story, is also based. So I called Herb Geraghty, executive director of Rehumanize International. He says he hasn’t worked with the reproductive justice group but knows of it and certainly would collaborate in many areas, like against police brutality, despite its abortion-rights position.

The “Venn diagram” of abortion attitudes

Rehumanize International and New Wave Feminists dispel stereotypes that all anti-abortion groups are church-attending Evangelicals or conservative Catholics. Geraghty started to understand his position against abortion in high school, around the same time he began to identify as a member of the LGBTQ community and as an atheist. “I sort of became reluctantly pro-life. I definitely wasn’t happy about it. I did not think it was cool,” he says.

New Wave Feminists counts college students, pacifists, independents, and agnostics in its ranks, as well as a religious following (although Ms. Herndon-De La Rosa says she lost many Protestants after she publicized her stance as “a very vocal ‘Never Trumper’”). She also says some abortion-rights activists work with her in Texas. They look away from her anti-abortion position, while providing “car seats and cribs and strollers and wipes and formula and diapers to women in need,” she says.

Lanae Erickson, senior vice president for social policy, education, and politics at the Third Way in Washington, which seeks consensus on tough issues, says politics fails to capture the “Venn diagram” of attitudes about abortion. “People’s feelings around these issues are complex, and politics makes them overly black and white. And so we put people in different categories, and the policymakers that represent them have very little overlap and are much more polarized than the general population.”

Ms. Herndon-De La Rosa, formerly Republican and now an independent, says she found herself stuck in the “Republican/Democrat binary,” in which she couldn’t find space to talk about humane treatment for immigrants, for example. She blames politicians for weaponizing women’s reproduction for their own political gain, starting in her home state.

“Texas could have invested in creating a true life culture that made it possible for women to choose life. And instead, it just pushed through a restrictive heartbeat bill,” she says. “One of the first things that I said [when it was passed] was, ‘I don’t think that this is going to save babies. I think it’s going to save politicians.’”

Now Ms. Herndon-De La Rosa says if Roe is overturned, handing abortion decisions back to states, it will split the country further between states that offer abortion sanctuary and those that pull “trigger laws” to effectively end it – with all the resources from the anti-abortion camp heading to the sanctuary states to fight the practice.

“The problem with that is there are still going to be pregnant women in states like Mississippi, Texas, or Louisiana. There’s women in those states who need housing, transportation, child care, and health care, especially in rural areas.”

Commentary

‘Heal everybody’: Rapper Kendrick Lamar as caretaker of culture

As Pulitzer-Prize winning rapper Kendrick Lamar takes his talents in a new direction, what does his body of work suggest about his influence on culture – and his own perseverance?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

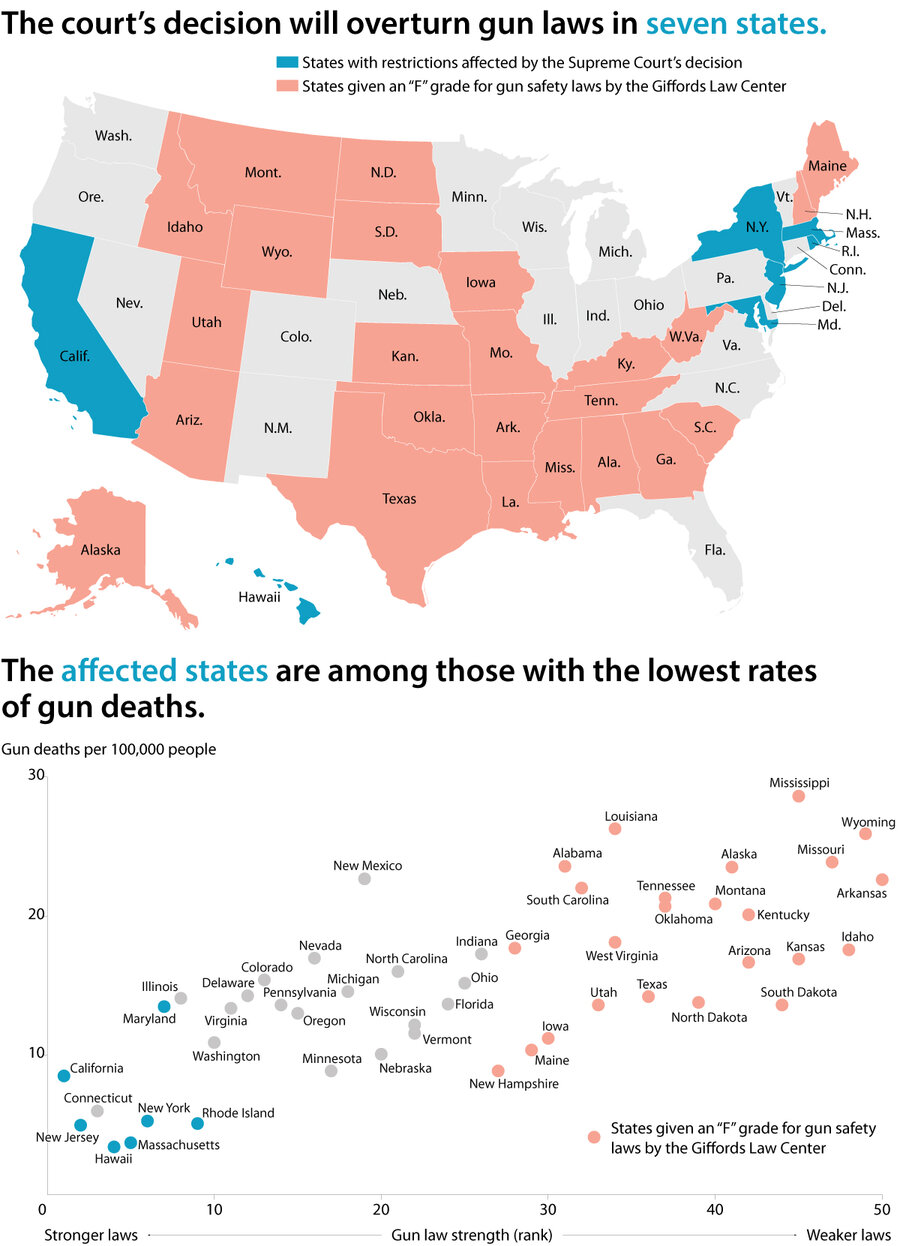

Prior to the debut last month of his latest album, “Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers,” rapper Kendrick Lamar released the fifth installment of his video series “The Heart.” Laced over a sample of Marvin Gaye’s “I Want You,” he provides a critical analysis of what “culture” means to Black people in America.

The video is Mr. Lamar at his cinematic and empathetic best, and it confirms why he is so beloved among fans. He has a way of humanizing tragedy, which is a lost art.

Even in the midst of massive celebrity, Mr. Lamar feels like he’s one of us. He doesn’t sound passé or preachy. He is as relevant and raw as ever, which constitutes so much of his legacy.

His lyrics, while profane, are piercing. Even when he approaches topics from flawed ideology, his sins are forgiven because of a willingness to convey the realities of life – his own and that of a society’s. As described on “Mother I Sober” off the new album:

I’m sensitive, I feel everything, I feel everybody

One man standin’ on two words, heal everybody.

‘Heal everybody’: Rapper Kendrick Lamar as caretaker of culture

Oftentimes, the best way to look at a cultural icon is through the prism of their contemporaries. Kendrick Lamar, arguably the best rapper in the industry and unarguably a Pulitzer Prize winner, took this a step further in one of his recent presentations.

Prior to the debut last month of his latest album, “Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers,” Mr. Lamar released the fifth installment of his series “The Heart” in a way befitting his legend. He uses deepfakes to morph into the likes of O.J. Simpson, Will Smith, Jussie Smollett, and Kanye West – plus the late Kobe Bryant and Nipsey Hussle. Laced over a sample of Marvin Gaye’s “I Want You,” he provides a critical analysis of what “culture” means to Black people in America.

He then ties that notion into a touching and tragic tribute for Mr. Hussle, a fellow rapper, who was killed in 2019 by a man whose trial is underway now in Los Angeles. The video is Mr. Lamar at his cinematic and empathetic best, and it confirms why he is so beloved among fans. He has a way of humanizing tragedy, which is a lost art, even in the age of mass media, relentless access, and the seemingly endless cycle of death and destruction.

The artist uses celebrities – no, celebrity – as an allegory for his own complex and controversial career. The same can be done to outline his upbringing and rise to superstar status. Mr. Lamar is a native of Compton, California, which is also where Venus and Serena Williams grew up. We have learned about the sisters as wunderkinds, who have since dominated tennis both as athletes and entrepreneurs. Where the Williams sisters were fathered into the game by their biological patriarch, Mr. Lamar had two chief figures who led him into celebrity – incomparable producer Dr. Dre, who only a few months ago headlined a nostalgic Super Bowl halftime show, and Anthony “Top Dog” Tiffith, who discovered the musician as a 16-year-old up-and-coming rapper.

His future plans also mirror those of Shawn “Jay-Z” Carter, who has gone from “best rapper” status to so much more than rap. We don’t just recognize him as a rap impresario: Through his partnerships with the NFL and others, we note his status as mogul and business adviser. Mr. Lamar has confirmed that his latest album will be his last on the label Top Dawg Entertainment, as he wants to become more of an entrepreneur.

It was almost 20 years ago when Jay-Z said that “The Black Album” would be his last, a marketing ploy, for certain, and yet, it announced that he would be more than an entertainer. Whether “Mr. Morale” will be Mr. Lamar’s last is less important than his growth as a person.

Even in the midst of massive celebrity, Mr. Lamar feels like he’s one of us. Five years after his last album release, he doesn’t sound passé or preachy in his songs or the video. He is as relevant and raw as ever, which constitutes so much of his legacy.

His lyrics, while profane, are piercing. Even when he approaches topics from flawed ideology, his sins are forgiven because of a willingness to convey the realities of life – his own and that of a society’s. As described on “Mother I Sober” off the new album:

I’m sensitive, I feel everything, I feel everybody

One man standin’ on two words, heal everybody.

He is not perfect, but he is a pastor of sorts. As displayed on “The Heart Part 5,” he is full of fire and brimstone, then suddenly compassionate. He is a modern-day Tupac Shakur, conflicted, conscious, unrelenting. California love, indeed.

Where Mr. Shakur’s life was tragically cut short at age 25, Mr. Lamar just celebrated his 35th birthday with family and friends. While he is still relatively young, it feels as if he has lived a few lifetimes.

Adversity will do that to you. As described by the musician in various lyrics, he has dealt with everything from depression to sex addiction to proximity to various abuses. Where that journey may have doomed a lesser man, it seemingly made Mr. Lamar stronger. The way that he wears his heart on his sleeve, not just fashionably, but functionally, is a refreshing example in a world that would rather say, as Charles Barkley once did, “I am not a role model.”

Humanity, hope, and healing. These are the cornerstones of Kendrick Lamar’s legacy, and if the last words of his latest album are any indication, he is ready to prioritize self-reflection over community critique:

Sorry I didn’t save the world, my friend

I was too busy buildin’ mine again.

Ken Makin is the host of the “Makin’ A Difference” podcast.

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to correct information about Serena and Venus’ time in Compton, California. They grew up there.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A turn away from political violence

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In its public hearings, the House panel investigating last year’s attack on the U.S. Capitol has sought to establish that there is no credible basis for claiming the 2020 presidential election was stolen. “Until we get a grip on telling people the truth,” Illinois Rep. Adam Kinzinger, one of two Republicans on the committee, warned his colleagues Tuesday, political violence may continue.

Many Republican officials and candidates are still encouraging their supporters to believe the lie of election fraud that motivated the mob on Jan. 6, 2021. Yet as in many countries recovering from a major conflict, the value of truth as a remedy for violence resides less in official narratives than in the contrition shown by individuals who had embraced violence as a legitimate means of political expression.

This idea of relying on remorse may now be changing the tone of justice in the United States as courts hear cases of more than 800 people, so far, charged with crimes related to the Capitol attack as well as violence during anti-police protests in 2020. Some of those trials are showing that empathy may be a more powerful tool of justice than fear of punishment in breaking a person’s attraction to violence.

A turn away from political violence

In its public hearings, the House panel investigating last year’s attack on the U.S. Capitol has sought to establish that there is no credible basis for claiming the 2020 presidential election was stolen. “Until we get a grip on telling people the truth,” Illinois Rep. Adam Kinzinger, one of two Republicans on the committee, warned his colleagues Tuesday, political violence may continue.

Many Republican officials and candidates are still encouraging their supporters to believe the lie of election fraud that motivated the mob on Jan. 6, 2021. Yet as in many countries recovering from a major conflict, the value of truth as a remedy for violence resides less in official narratives than in the contrition shown by individuals who had embraced violence as a legitimate means of political expression.

This idea of relying on remorse may now be changing the tone of justice in the United States as courts hear cases of more than 800 people, so far, charged with crimes related to the Capitol attack as well as violence during anti-police protests in 2020. Some of those trials are showing that empathy may be a more powerful tool of justice than fear of punishment in breaking a person’s attraction to violence.

Consider this exchange in a federal court in Portland, Oregon, on Tuesday. The defendant, Malik Fard Muhammad, had traveled from Indiana in 2020 to participate in mass protest rallies against police violence. When the event turned tense, he threw Molotov cocktails at officers. U.S. District Judge Marco Hernandez wanted to understand why.

“I was just wondering what your thought process was that suddenly put you in the position where you thought that this was OK, this was the thing to do, where people could get hurt or killed. I’m having trouble grasping how you got there.”

“I’m having trouble with it, too,” Mr. Muhammad said. “I felt unheard and dismissed and things just escalated to the point that I can’t take back.” He added: “I just regret my decisions. ... I’m here now to atone for them.”

A similar approach may be working in the most serious charges yet brought against defendants tied to the Capitol mob. Eleven people face charges of sedition and obstruction of official proceedings. Among the accused are the leader of an extremist group called the Oath Keepers and several of his foot soldiers. All allegedly espoused violence and arrived at the Capitol armed. Two have already pleaded guilty.

One, a man from Georgia named Brian Ulrich, wrote in an encrypted chatroom prior to the attack, “And if there’s a Civil War, then there’s a Civil War.” Fifteen months later, standing before U.S. District Judge Amit Mehta in Washington, D.C., he fought to compose himself as the judge read the terms of an agreement for his cooperation that did not shield him from high fines and prison. “Mr. Ulrich,” the judge asked, “do you need a moment.” The defendant urged Judge Mehta to continue. “It’s not going to get any easier.”He then took a moment to weep.

At a time when threats of violence against public officials seem to be on the uptick and many Jan. 6 defendants are taking plea deals to avoid jail time, the courtroom exchange between Judge Mehta and Mr. Ulrich offered a hint of something different – a turn away from violence and the lie that sparked it, marked by remorse and a magistrate’s compassion.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Being a lie detector

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By David Tomko

An openness to the spiritual facts about God and His creation brings about healing and harmony.

Being a lie detector

The Bible is full of accounts of human needs being met solely through turning to God in prayer. These include the provision of food and shelter, the healing of disease, and safety from danger. These experiences span a range of peoples, locales, governments, and centuries. So what do they have in common aside from God and prayer?

In my study of Christian Science, I’ve found that the commonality is Christ, which Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, describes as “the true idea voicing good, the divine message from God to men speaking to the human consciousness” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 332). This divine message existed before Christ Jesus’ time and continues today. It is God’s truth and love correcting the lie of mortality – the lie of life and truth in matter – so that the spiritual harmony, already present, can be perceived.

Jesus clearly demonstrated the efficacy and reliability of detecting and correcting a material lie in order to uplift and improve human experience. He varied the prayer to address the individual need. But the truth being expounded – the truth of God and His constant care – did not vary. And the result was always the same: A lie about God’s creation was destroyed, and human experience shifted to manifest the immortal truth that man is governed by God alone.

We can be lie detectors and eliminate lies masquerading as truth in our consciousness. We recognize the lie by seeing clearly that any inharmony, however it is presented, could not be the truth about God’s always-harmonious creation, which the Bible describes as spiritual and good. Then we replace the material lie with the spiritual reality.

Mrs. Eddy writes (referring to Jesus), “Our Master, in his definition of Satan as a liar from the beginning, attested the absolute powerlessness – yea, nothingness – of evil: since a lie, being without foundation in fact, is merely a falsity; spiritually, literally, it is nothing” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 108).

How encouraging to know that evil is not included in God’s creation at all. Therefore, there is nothing permanent about evil – it is a lie about God and His creation. A mistaken concept.

Of course, there are times when recognizing the nothingness of a lie can be challenging – when a problem seems especially threatening, attention-getting, or stubborn. But we can confidently claim Truth’s dominion over any lie, since Truth is God, All, and therefore everywhere present.

Recently, after enjoying a dinner with my family, I went outside to put the grill away. I did not realize that it had been left on and had continued to heat during the entire time we were eating. As I touched the grill, I burned my hand, and the pain was immediate and intense.

I declared, pretty energetically and loudly, what I knew to be true about God’s creation, including me, as constantly maintained in harmony, constantly protected in divine Love. The pain abated quickly as I contemplated the spiritual facts. Material belief argues for accident as a possibility, pain as an outcome, and recovery as a process. It suggests that a gap in God’s protection of His creation could exist and allow my harmony to be undermined.

I prayed to realize what God knew of this situation. Because God is Spirit, His control had to be exactly the opposite of the material lies being presented as facts. Divine Love, encompassing its creation, does not allow for accidents or any inharmony. No gap in protection can exist.

Relief came when I detected the lie and remained firmly, vehemently rooted in what I knew was true. Within an hour all pain had left my hand, and by the time I went to bed that evening, there remained only a slight discoloration, which was fully gone when I awoke the following morning.

Whether a discordant situation seems to require shouting the truth of God’s, Spirit’s, perfect creation or a quieter listening to God to hear divine Truth and uncover the lie, we can trust that perfect Love, God, is forever at hand meeting our needs. Our confidence can always rest in Truth’s undefeated record of dispelling the lies of mortality and bringing harmony to light.

Adapted from an article published in the June 6, 2022, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Putting for birdie

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when our Henry Gass talks to an artist who wants you to lower the bat, take off the blindfold, and appreciate the piñata – an art form that dates back hundreds of years.