- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

In Today’s Issue

- Beset by challenges, can Biden turn things around?

- US and NATO allies get creative in aid for Ukraine

- Safe in Paris, Ukrainian artists try to inspire French compassion amid war

- Giving Black women in pop their due: Q&A with author of ‘Shine Bright’

- How a minor league team got more followers than the Yankees

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

In war, the call to help never ends

Anastasia Chukovskaya understands the challenges that Ukrainians fleeing Russia’s invasion face. As you may recall from a piece I wrote in April, she and her husband, Russians who live in Budapest, Hungary, leaped into action to help refugees arriving in their city with little idea what to do next.

I checked in with her over the weekend, and it's clear they’ve stayed busy. Ms. Chukovskaya’s persistence has helped many families find shelter and resulted in the Learning Without Borders school that supports 60 Ukrainian students, 15 Ukrainian teachers, and 10 Hungarian staff members. Now, she’s tackling a new challenge: providing food to struggling refugees.

“It makes me so stunned that there are food-deprived people,” she says. “I can’t believe food can be such an issue in such a time.”

Thus her new effort: hunhelp.com. Refugee applications speak to the need – the family in Mariupol who lived with their baby in a basement for a month after their apartment was burned down, the older couple who fled a town occupied by Russians. One woman wants to work, but can’t leave her adult son, who has a disability, alone.

Ms. Chukovskaya works with whomever she can – small nongovernmental organizations, large aid groups, businesses whose employees run donation drives. Hurdles loom large: minimal state aid, bureaucratic restrictions, overwhelming demand, even public perceptions about favoring foreigners over poor Hungarians. “There is a shop which gives us supplies in several cities, but they are not public about it,” she says.

Yet as of this week, her organization has fed 1,000 people. “I would love it to be 10,000 to 20,000,” she says.

Indeed, as she looks to the winter, her focus is on scaling up – and she’s persisting in keeping refugees’ needs in the public eye as the war grinds on. So she and her colleagues crowdfund and cajole, tapping any contacts she can think of, anywhere. “I am a network builder,” she says. “My friends say, ‘This is how social capital works.’ I am very fortunate in that sense.”

She worries the war feels like “old news” to many people now. “But I also have had messages asking, ‘Is it too late to help?’ Every day brings a lot of disappointment, but also brings a lot of support.

“I see I should go where the need is urgent.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Beset by challenges, can Biden turn things around?

President Joe Biden won because he was seen as a unifier. Now, even many Democrats say they want a different kind of leader. But other presidents have had rough starts – and recovered.

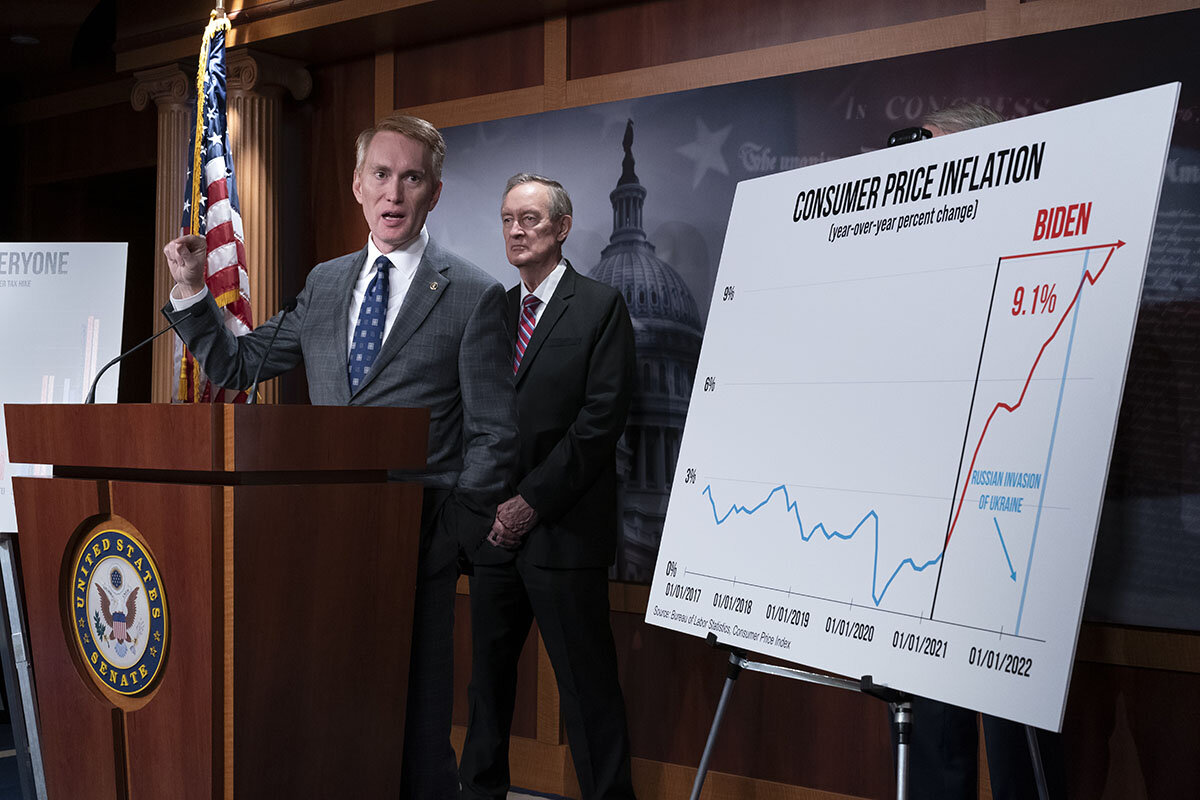

President Joe Biden can’t seem to catch a break. Inflation is crushing consumers, while recession looms over the economy. Gun violence is raging, and COVID-19 cases are rising. The baby formula shortage persists, and so on.

Mr. Biden’s average job approval rating at this point in his tenure – 38.5% – is now the lowest of any president since World War II.

If Ronald Reagan was the Teflon president – bad news often just slid off, it seemed – Mr. Biden may be the Velcro president. Everything sticks.

It’s worth noting that the party that wins the White House almost always loses seats in congressional elections two years later. Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama all won reelection despite losing ground in their first midterms.

Mr. Biden, in some ways, has the worst of all possible worlds. His party controls both houses of Congress, creating the appearance of power, but Democrats’ extremely narrow majorities make it very difficult to get anything done.

“The person in charge always gets way too much credit when things are good, and way too much blame when they’re bad,” says former Republican strategist Dan Schnur. “Biden’s not all that unique in this regard.”

Beset by challenges, can Biden turn things around?

President Joe Biden can’t seem to catch a break. Inflation is crushing consumers, and gas prices, while going down, are expected to rise again – possibly just in time for the November midterms. The R-word, recession, looms over the economy. Gun violence is raging. COVID-19 cases are rising again. The baby formula shortage persists. And on and on.

All American presidents live or die, politically, by the headlines – whether or not the bad news is their fault. But President Biden seems to have it worse, with the lowest average job approval rating at this point in his tenure – 38.5% – of any president since World War II.

If Ronald Reagan was the Teflon president – bad news often just slid off, it seemed – Mr. Biden is the Velcro president. Everything sticks.

“The person in charge always gets way too much credit when things are good, and way too much blame when they’re bad,” says former Republican strategist Dan Schnur. “Biden’s not all that unique in this regard. What’s different is the level of unhappiness, not just from the other side or even from swing voters, but from his own base.”

Indeed, the latest New York Times/Siena College poll shows Mr. Biden’s job approval at just 70% among Democrats. And a whopping 64% of party members say they want someone else as their standard-bearer in the next presidential election.

Mr. Biden’s age, close to 80, is his biggest liability, according to the poll. Democrats ranked it as the top reason to find an alternative for 2024. It’s not just the number itself – it’s the sense that he’s slowed down. Taking a tumble from his bike last month while on a getaway in Delaware, photos and video of which went viral, didn’t help.

Democratic activists want a fighter, says Mr. Schnur, who teaches at the University of Southern California and the University of California, Berkeley and is now a political independent. “They want someone who will yell and scream and threaten the other side with destruction. That’s not who Biden is.”

Ironically, two years ago, Democrats nominated Mr. Biden because he was seen as a unifier, not a partisan warrior – an experienced Washington hand who could defeat President Donald Trump and bring back “normalcy.” Mr. Biden succeeded in unseating Mr. Trump, and now many party activists seem to want their own version of the former president.

But for the time being, Mr. Biden occupies the Oval Office, and the question is, can he get his presidency back on track? And are there any lessons from history that he can take to heart?

It’s worth noting that the party that wins the White House almost always loses seats in congressional elections two years later – sometimes a lot of seats. Mr. Reagan didn’t become the Teflon president until after his party did poorly in the 1982 midterms, when the recession of the early ’80s – with unemployment topping 10% – helped Democrats net 26 House seats and one Senate seat.

Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama all won reelection despite losing ground in their first midterms. Presidents Jimmy Carter and George H.W. Bush, by contrast, were one-termers.

Mr. Biden – or the Democratic nominee, if Mr. Biden opts out – could well go the way of Presidents Carter and Bush, particularly if the economy is still wracked by high inflation in 2024 and possibly in recession. The Democrats can be credibly blamed for underestimating the risk of inflation as they spent big in 2021. And the old Clinton-era campaign mantra that sent the first President Bush into retirement after one term still holds: “It’s the economy, stupid.”

Control of Congress – but barely

Mr. Biden, in some ways, has the worst of all possible worlds. His party controls both houses of Congress, creating the appearance of power, but Democrats’ extremely narrow majorities make it very difficult to get anything done.

Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, a Democrat representing one of the most Republican states in the country, crushed his party’s dreams Thursday when he declined to back Mr. Biden’s climate change measures in an already slimmed-down Build Back Better bill. In a 50-50 Senate, with the vice president as the tiebreaker, one dissenting Democrat is all it takes to squash a deal. Now the party is trying to pass an even smaller spending package focused on health care, lowering prescription drug costs and maintaining insurance subsidies in the Affordable Care Act.

That’s not nothing – far from it, say Democratic strategists, who urge Mr. Biden and his surrogates to publicize his administration’s accomplishments and project optimism heading into November. And yes, they add, Democrats have to bring the fight, particularly on matters of profound consequence, such as the Supreme Court’s June decision that overturned the nationwide right to abortion. The White House’s seemingly muted initial response to the ruling confounded some Democrats, especially after the leaked draft of the decision provided advance warning.

Karen Finney, former communications director for the Democratic National Committee, says Mr. Biden and the Democrats have a positive story to tell, and rattles off issues: On COVID-19, there’s the nationwide distribution of vaccines and therapeutics. On infrastructure, there’s the years-in-the-making passage of bipartisan legislation that will bring tangible benefits around the country. On guns, there’s the just-passed gun safety measure – the first to pass in decades, and again, with bipartisan support.

“Governing is still campaigning in so many ways,” Ms. Finney says. “You have to get out there and say, ‘Here’s what we’ve done; here’s what we’re going to do.’ Make it about the future.”

Ann Lewis, former communications director in the Clinton White House, urges perspective in the face of bad polls.

“I’m a Biden optimist,” Ms. Lewis says. The polls that show most voters see the nation as on the wrong track are “a national feelings thermometer,” she adds. “But as we get closer to the election, they will reflect a choice. Joe Biden will do better when it’s a choice.”

Even now, she notes, Mr. Biden would beat Mr. Trump 44% to 40% in a rematch if the election were held today, according to the Times/Siena poll.

As for progressive groups that are already openly calling on Mr. Biden not to run for reelection, Ms. Lewis is dismissive. “They tend to be the kind of people who’ve always believed that if only Democrats would say what they think, we’d do better,” she says.

Looking to this November, one critical factor is whether Mr. Trump announces another run for the presidency before the midterms. If he does, most Democrats see that as a gift to their side, giving their party a foil to run against.

A series of gaffes

Still, the at-times bad optics around Mr. Biden’s public actions are a regular source of discomfort for Democrats. The president’s fist bump Friday with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman – a man Mr. Biden once pledged to treat as a “pariah” over the 2018 murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi – will be the enduring image of a visit that likely won’t bring immediate benefit to Americans.

Foreign policy, in general, isn’t likely to boost Mr. Biden’s domestic political fortunes, not even his widely praised role in rallying NATO after Russia invaded Ukraine. More often, it’s the blunders abroad – such as the United States’ chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan last summer – that voters remember.

Closer to home, Mr. Biden’s at-times shaky performance as a public communicator can be hard to escape. On July 4, at a picnic on the South Lawn of the White House for military families, Mr. Biden’s remarks barely touched on the mass shooting that had taken place that day in Highland Park, Illinois.

But presidential historians aren’t ready to write Mr. Biden off.

“Politics obviously changes very fast, and political fortunes can turn around very quickly,” says Matthew Dallek, a professor at the George Washington University Graduate School of Political Management. “That’s not to predict that Biden’s will – I have no idea,” he adds. “But I don’t think Biden is as much of an outlier at this moment as he might appear to be.”

The attacks on Mr. Biden’s age and acuity may be resonating more because of the many challenges the country faces. And, Professor Dallek says, “on a handful of issues Biden has appeared to be slow to react or not as aggressive as maybe some of his critics would like him to be.”

That’s a different dynamic from, say, former Presidents Clinton or Obama, who were seen as rising leaders of a new generation. But Mr. Dallek notes, “The narrative sometimes flips and there’s a comeback story. I’m not ready to write Biden off, at least just yet.”

US and NATO allies get creative in aid for Ukraine

Does the term “proxy war” apply to a conflict that is formally between Russia and Ukraine? Whatever you call it, the U.S. and NATO are using ingenuity to affect the outcome while keeping war at arm’s length.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Russian President Vladimir Putin has repeatedly accused the United States of waging a proxy war in Ukraine, and he’s not entirely wrong, U.S. military analysts say.

But the definition of proxy war is a loose thing. In aiding Ukraine, the U.S. and its NATO allies have national security interests that go beyond Ukraine’s own freedom and territorial integrity. Still, military experts note that Russia invaded Ukraine without provocation and against international warning. NATO is not arming proxies to stir up wars they wouldn’t otherwise be engaged in.

The U.S. and NATO are “obviously pushing some red lines” in efforts to impede the Russian invasion, but “we ought to do that,” says Sean McFate, a professor at National Defense University who served in the U.S. Army. To date, this has involved tapping into a deep well of ingenuity to do everything from getting weapons into the hands of fighters to training them off the battlefield.

As fighting in Ukraine stalemates, “covert” resourcefulness should increasingly come into play as well, many military analysts say. “We will need to fight a sneaky war,” says Dr. McFate. At the same time, avoiding direct NATO engagement is key to avoiding escalation of the conflict.

US and NATO allies get creative in aid for Ukraine

Russian President Vladimir Putin has repeatedly accused the United States of waging a proxy war in Ukraine – most recently on July 7 – and he’s not entirely wrong, U.S. military analysts say.

But proxy war is a very loose thing in international law, and whether the U.S. is in one with Russia, many add, matters less than whether the U.S. and its NATO allies can continue to push red lines without prompting a Russian reprisal that officially draws the alliance into war.

“If you ask lawyers, or a military general, they all have a different answer on whether or not this is a proxy war. It’s very relative,” says Sean McFate, a professor at National Defense University who served in the U.S. Army. “The answer is that it’s where Putin’s ego ends and Russian foreign policy begins. It’s a moving line that depends very much on perception.”

True, if Russia was giving aid to Al Qaeda in Iraq, “we’d view this as going over some line perhaps,” Dr. McFate notes. That said, while the U.S. was attacked by Al Qaeda, Russia invaded Ukraine without provocation and against international warning – and NATO is not arming proxies to stir up wars they wouldn’t otherwise be engaged in.

And while the U.S. and NATO are “obviously pushing some red lines,” he adds, “we ought to do that.” To date, this has involved tapping into a deep well of ingenuity to do everything from getting weapons into the hands of fighters to training them off the battlefield.

As fighting in Ukraine stalemates, “covert” resourcefulness should increasingly come into play as well, many military analysts say. “We will need to fight a sneaky war, with maximum plausible deniability,” says Dr. McFate. “We layer the fog of war and move through it for our red-line pushing.”

At the same time, this will necessarily involve asking some tough questions about how far NATO is willing to go to help Kyiv win. “It’s one thing to say that the U.S. and Ukraine share an interest in ensuring that Russia isn’t able to wage future aggression,” says Anthony Pfaff, the research professor for strategy, the military profession, and ethics at the Strategic Studies Institute of the U.S. Army War College.

“But the kinds of costs we may be willing to pay for those things is very different.”

A Twitter-based handbook

When war broke out in Ukraine, retired Maj. John Spencer started tweeting advice for civilians who wanted to “go out and resist” the Russian invasion in any way they could.

Chair of Urban Warfare Studies at West Point’s Modern War Institute, Mr. Spencer, who had served two combat tours in Iraq, sought to encourage would-be fighters by noting that in 2016, it took more than 100,000 U.S. and coalition troops nine months to recapture Mosul from an estimated 5,000 to 10,000 Islamic State fighters, many of whom were wearing flip-flops.

The tweets were collected into a “manual for the urban defender,” which was posted online by the Ukrainian government. (Mr. Spencer signed over the copyrights for free.)

The handbook urges Ukrainians to block roads with anything available, from dump trucks to trash, and never to sit around. “You’d be surprised at the depth and length of a tunnel a team of civilians can dig in just a few days,” he writes.

To address dire defensive circumstances, the manual offered tips for booby-trapping homes, including knocking out floorboards beneath easy-to-access windows, cutting electricity at night (since dark offers an advantage to homeowners), and running razor wire at neck level across doorways to slow down intruders and provide a brief window for escape from Russian soldiers.

With weapons and advice flowing into Ukraine, Mr. Spencer is philosophical about whether it qualifies as a proxy war. “The definition of ‘proxy’ is very loose. Clearly Ukraine is fighting Russia for us, for Europe, for democracy,” he says. “When we supply them with weapons, how is that different to supplying the mujahideen?”

That said, it’s “not like they’re asking anyone to fight for them,” he notes. “And it’s not like we’re arming proxies to start and fight wars that they wouldn’t otherwise be engaged in.”

Past lessons on insurgency

In the months to come, Mr. Spencer imagines that Ukrainian fighters will draw upon “years of Special Forces and paramilitary lessons going back to World War II about how to create resistance in occupied areas.”

The U.S. practiced counterinsurgency warfare for nearly two decades in its most recent wars. Now NATO needs to turn those lessons around fighting as insurgents, says Dr. McFate of National Defense University.

There was an old adage in Kabul, for example, that while the Americans had the watches, the Afghan insurgents had the time.

“If you’re David and the enemy is Goliath, you can weaponize time, and win by not losing,” he says. “As long as there’s a resistance movement – even if Russia does take Kyiv – Russia can never claim victory. And we can easily maintain that.”

Poland and Romania could also host NATO bases where Ukrainian “guerrillas can cross the border covertly. We arm, equip them, give them rest. We keep them alive,” Dr. McFate adds. “And as long as they’re alive, Putin isn’t winning.”

At the same time, “we shouldn’t be stupid,” he warns.

Reckless measures, in his estimate, include NATO “overtly placing soldiers in Ukraine, or boots in the air, or boots at sea.” If NATO vehicles or vessels were fired upon, it could launch “a tripwire that sucks NATO officially into that war – and that is really bad news, especially if Putin thinks he can get away with a limited nuclear war in the name of defense.”

What role for a rocket system?

In an existential war, Ukraine is going to be willing to pay a far higher price for its freedom than NATO. And so, given the support they’re providing Kyiv, the U.S. and its NATO allies must be clear with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy about what the alliance is willing – and not willing – to do, says Dr. Pfaff of the U.S. Army War College.

Ukrainian forces, for example, have been supplied with their most advanced weapons system to date, courtesy of the U.S. government.

The High Mobility Artillery Rocket System, or HIMARS, developed for the U.S. Army, is now the longest range of Ukraine’s ground weapons, at nearly 50 miles. The U.S. has supplied it with the understanding that it be used to strike Russian targets within Ukraine – but not within Russia.

“Giving them HIMARS is a fine thing to do if you just have dead Russian soldiers, but not if you have dead Russian civilians” as a result of artillery barrages into Russian territory, says Dr. Pfaff.

Yet Kyiv could easily argue that using HIMARS against Russians outside Ukraine is the only way to win, he adds.

“They haven’t made that argument yet, but I can see them turning around and looking at us and saying, ‘We need to do this.’”

The U.S. and NATO must plan for these scenarios in advance – and make clear their own red lines with Kyiv – particularly since the West’s military intervention allows Ukraine “to do things it might not otherwise do,” Dr. Pfaff notes.

These are key considerations as Mr. Putin promised recently that his war has just begun. “Everybody should know that largely speaking, we haven’t even yet started anything in earnest,” he told Russian parliamentary leaders.

“Basically, it’s kind of a simple formula,” Dr. Pfaff says. “The more support we give Ukraine – and the more effective that is – the more the Russians are going to want to escalate.”

Editor’s note: A sentence in this article has been updated to correct John Spencer's rank; he is a retired major.

Safe in Paris, Ukrainian artists try to inspire French compassion amid war

By providing a safe haven for Ukrainian artists, France is offering them a feeling of home while also creating a connection between the French public and some of Ukraine’s prized cultural offerings.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Innumerable Ukrainian artists and cultural figures have found themselves in exile in France since the Russian invasion began on Feb. 24. They join the nearly 100,000 Ukrainian refugees currently in France and the more than 5 million across Europe.

As the war continues into its fifth month, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has expressed concern that the world is experiencing “Ukraine fatigue,” telling Canadian students at the end of June, “Don’t forget about what’s happening in Ukraine.”

Art has been one way of humanizing the conflict, as more Ukrainian artists flee home and continue their craft in exile. The effect of their art has been twofold. For artists, making and sharing their work has been a way to channel difficult emotions surrounding the war. For the French public, experiencing Ukrainian art and culture has put a personal face on the war and built compassion for a resolutely independent Ukraine.

“You can’t just keep showing the same images of war on the news,” says Viktoriia Gulenko of the Cultural Center of Ukraine in France. “Our goal is to show a positive image of Ukraine and open up our cultural traditions to the French, in order to build a lasting link between people.”

Safe in Paris, Ukrainian artists try to inspire French compassion amid war

Kristina Kadashevych sails into the air in a pale blue leotard, legs outstretched in a leap. As her feathery frame floats back to the ground, her fellow company members stand in position, arms raised delicately overhead.

This is just a rehearsal for the Kiev City Ballet, whose 38-member-strong company has been in exile in France since arriving for a national tour just as the war in Ukraine began. But Ms. Kadashevych says that every time she performs for a live audience, she is overcome with emotions.

She’s from the eastern city of Zaporizhzhia, whose nuclear power plant was taken over by Russians in March. It was around then that her family fled to the west of Ukraine, and she decided to leave her parents and 3-year-old son to join the Kiev City Ballet in Paris.

“It’s horrible to be away from my son, but I needed to work,” says Ms. Kadashevych, after a rehearsal at the Théâtre du Châtelet, where City Hall has lent the dancers practice space. “In some ways, dancing helps me to stop thinking about [the war]. When you’re dancing, you only think about dancing. But when I see people waving Ukrainian flags at the end of a show, every time I begin to cry.”

Dancers from the Kiev City Ballet are just some of the innumerable artists and cultural figures who have either fled Ukraine or found themselves in exile in France since the Russian invasion began on Feb. 24. They join the nearly 100,000 Ukrainian refugees currently in France and the more than 5 million across Europe.

As the war continues into its fifth month, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has expressed concern that the world is experiencing “Ukraine fatigue,” telling Canadian students at the end of June, “Don’t forget about what’s happening in Ukraine.”

Art has been one way of humanizing the conflict, as more Ukrainian artists flee home and continue their craft in exile. The effect of their art has been twofold. For artists, making and sharing their work has been a way to channel difficult emotions surrounding the war. For the French public, experiencing Ukrainian art and culture has put a personal face on the war and built compassion for a resolutely independent Ukraine.

“You can’t just keep showing the same images of war on the news. After a while, people get tired and they don’t respond to it anymore,” says Viktoriia Gulenko, the director of the Cultural Center of Ukraine in France, which has held numerous events in the last months.

“Our goal is to show a positive image of Ukraine and open up our cultural traditions to the French, in order to build a lasting link between people. It’s only by way of culture that we can achieve this.”

“Being here is like connecting the dots”

Around 20 women – a mix of French and Ukrainian – are seated around a long card table, bent over their wooden spoons and paint palettes. Olena Shaposhnyk, a professional artist who arrived from the city of Dnipro three months ago, moves around the table in a vibrant blue blazer, stopping sporadically to give instructions.

This workshop at Paris’ Cultural Center of Ukraine is on the traditional Petrykivka painting style, included in UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage since 2013. It is often used to decorate the facades of buildings and houses, with symbolic images like the tree that represents a growing family or – today’s lesson – the sunflower, a symbol of protection.

“Ukrainian culture and art are incredibly rich, their ability to use color is extraordinary. Just look at their scarves, the embroidery, the jewelry,” says participant Odile Kudryk, a Frenchwoman whose mother was Ukrainian. “I have this strong desire to be with the Ukrainian people right now, but obviously I can’t go there. Being here is like connecting the dots.”

The feeling is mutual for Ukrainians far from home during the conflict. Anastasia Gerasymovska, who came to Paris from the west-central city of Vinnytsia eight years ago, says she’s never done this type of painting before. “I’ve seen this since I was a little girl. It really brings me back home.”

Paris’ Cultural Center of Ukraine, like other nonprofits here, has greatly increased its programming since the war began to meet the demands of the French to learn more about Ukrainian culture. Their audiences and participants are a mix of Ukrainians and French.

They recently asked Ukrainian artists living here to express their emotions about the war in a politically charged mural on one of the center’s interior walls, in partnership with students from the Paris Academy of Fine Arts.

The center’s director, Ms. Gulenko, says they’ve worked hard to find a balance between pure art and hidden messages, to keep the public engaged but also combat misinformation. A March Ifop poll showed that more than half of French people believed at least one Russian propaganda narrative about the war.

Equally, the #KidsDrawPeace4Ukraine project sits at the crossroads between art and hard news, and has worked to build empathy for Ukrainians among the youngest members of the public. The joint effort of news organizations around the world calls on young people to create art that wishes peace and love for the children of Ukraine. The drawings, which are posted on social media, have been an outlet for children to express their compassion and support for Ukrainians.

The project has since asked refugee children to create their own images, and adults have noticed that, oftentimes, the drawings from French and Ukrainian children are no different from one another.

“There is a magnetic power in art and pictures,” says Aralynn Abare McMane, executive director of Global Youth & News Media, a French nonprofit that organized the project. “[This project] really helped people see the children’s hopes for peace. They felt connected. From Ukrainians, we heard, ‘it’s great to know someone is thinking of us.’”

Singing about the war

Just as the nonprofit world mobilizes to teach the French about Ukrainian art and culture, the French government has, in turn, committed to supporting Ukrainian artists and cultural professionals exiled by the war. In March, the Ministry of Culture pledged €1.3 million ($1.32 million) to help cultural refugees, which includes an emergency reception system, support for artistic creation, and help with French language learning.

The French artistic community has also come together in support of Ukraine, with cultural institutions like the National Opera, the Paris Philharmonic, and the Avignon Festival expressing their solidarity. On March 4, the country’s public television operator France Télévisions broadcast a live, five-hour-long vigil in support of Ukraine at the Théâtre National de Chaillot in Paris.

In that vein, Estelle Delavennat, a Paris-based singer, helped organize an event in early July at a local bookstore, where French and Ukrainian artists joined forces in song, theater, and folklore.

“The feedback from the people who attended was obviously great. There was a man who was so sad that he’d forgotten to record one of the theater scenes because it captivated and moved him so much,” says Ms. Delavennat.

“Cultural events can help the French public better understand what’s happening in Ukraine right now by allowing them to take the long view and see the larger perspective, whether it’s in the form of music, cinema, or theater.”

Up on the top floor of the Ukrainian Cultural Center, three panels of tropical-colored stained-glass windows shimmer as Julia Poliuliah plays the piano and sings traditional Ukrainian folk songs for a small audience. Many are about war, and Ms. Poliuliah says that, like Ms. Kadashevych of the Kiev City Ballet, she has used art as a way of processing her emotions about the conflict.

Her 57-year-old father recently joined Ukraine’s military effort – even after a stint in the hospital diagnosed with severe COVID-19 – after seeing so many young men risking their lives for their country. She can’t help but worry.

“Before the war, these songs were historical for me. Now, it’s completely different,” says Ms. Poliuliah, who moved to Paris before the war began. “When I sing about a couple where the man leaves for war, I can’t keep my feelings inside. Now, when I sing, I cry. I dream that this war ends immediately.”

Books

Giving Black women in pop their due: Q&A with author of ‘Shine Bright’

Motivated by a determination to set the record straight, journalist and author Danyel Smith stakes a claim for the pivotal role of Black women in pop music.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

-

By Ken Makin Contributor

Journalist and podcaster Danyel Smith uses her voice to uplift and celebrate the Black women whose histories and careers typically started with less wealth and opportunity than those of white pop stars.

Her latest book is as much a memoir as it is an appreciation for Black women in music. “Shine Bright: A Very Personal History of Black Women in Pop” weaves together Ms. Smith’s upbringing in Oakland, California, with the childhoods of icons such as Aretha Franklin, Gladys Knight, and Mariah Carey.

“There’s so much ambition in the sound,” she says. “I began to ask myself, ‘Where does this come from? Why is it so intense? Why is it so successful? Why is it so influential?’ And one of the many things is that many of the women were born into segregation.”

She continues, “I wanted to know where that sound, that striving for bigness and perfection came from. And I think it comes from being treated unfairly, being treated with ugliness, being forced into a caste system.”

Ms. Smith is determined to provide historical context. “Music doesn’t just come out of nowhere. When we were in the fields, it came from the pain of all of that. So why wouldn’t the sound of Black pop come from something as well?”

Giving Black women in pop their due: Q&A with author of ‘Shine Bright’

Journalist Danyel Smith is determined to claim the rightful place of Black women in pop music. It’s a subject she knows inside out, as both a cultural critic and a self-described super fan. She uses her voice to uplift and celebrate the women whose histories and careers typically started with less wealth and opportunity than those of white pop stars.

Her tenacity has led her to create and produce the podcast “Black Girl Songbook.” Her career has included stints as a senior producer at ESPN and editor at Billboard, Time Inc., and Vibe. She also has two novels to her credit: “More Like Wrestling” and “Bliss.”

Her latest book is as much a memoir as it is an appreciation for Black women in music. “Shine Bright: A Very Personal History of Black Women in Pop” weaves together Ms. Smith’s upbringing in Oakland, California, with the childhoods of icons such as Aretha Franklin, Gladys Knight, and Mariah Carey.

She spoke recently with the Monitor about her determination to set the record straight, her commitment to journalism and advocacy, and how Black women are the linchpin of pop music.

What inspired you to write the book?

I don’t know if I wanted to write it as much as I felt there were things that needed to be said. There are many things in the world of music, journalism, and music criticism that are written around, and I wanted to approach them directly, particularly in regard to Black women in pop music.

It began to feel like a pull, like a duty to create the book; it was similar to the pulls that I felt working in editorial and working for publications like Vibe. Over the course of my career, it feels like I’ve been in service to the culture in one way or another. That’s a long way of saying that “Shine Bright” is a service to the culture and I feel called to it.

You’re speaking about service through reporting, but also advocacy. Can you talk about that?

So often, what gets attached to the idea of advocacy is that somehow you are not being fair to all parties, or that you are somehow biased toward one group. I just don’t think that is true. Advocacy means I have a familiarity with the culture, the context, the characters, the situations, and the history.

What that means for me is I know just how much of all of that has been overlooked with regard to Black people and in particular Black women. I felt very similarly about the art of hip-hop. When I first got into my career, everyone – and by everyone I mean the mainstream media and culture – was referring to hip-hop as a fad. It wasn’t a “real art form.” It was “terrible.” Everybody was going to go downhill into hell immediately because of the sound of the music. I knew that not to be true. I knew the power of rap almost from its beginnings. I had an inkling of what was to come based on the history of the music that Black people create, whether it’s rhythm and blues, jazz, soul, or pop, we continue to create things that influence global culture.

So it didn’t take a genius to realize that’s what was coming with rap. I also just knew experientially how it was making me as a Black woman feel. So I don’t think that advocacy is a bad word. I feel like advocacy is a banner of truth and it’s getting to what’s actually real. And yes, I have practiced [advocacy] as often as I can, I practice it now, I practiced it then, and I will practice it in the future.

How has being overlooked shaped your life personally?

It’s affected me in all ways on all days. It’s never not affected me and it’s not that I’m guessing. I’ll just give one example. It’s affected me financially over the course of my career. And I say this because I’m married to a man who has had the same jobs that I’ve had in this business. And so I’m privy to what his salary has always been as compared to what mine has always been. It’s insane the difference, and he’s a Black man. I can’t imagine the difference, or I should say, I can very clearly imagine, how much more different it would be if he was a white male.

What was your creative process like in curating the book?

It changed as I became more committed to getting it done. At first, it seemed like a cool project that I needed to do, so I would devote the time to it, and that was convenient for me. I was teaching and then I was at ESPN, and I was doing a lot of writing, editing, and producing at ESPN. It didn’t leave a lot of time for doing my best work outside of the main job. But then when I started working again with (publisher) Chris Jackson at One World, he was asking me why I wasn’t finishing the book, and I had no good answer for him, especially because I wanted to finish it. And he said, “I think you need to claim your space as a Black woman in pop music and write about your experiences as it relates to the experiences of the women that you have so beautifully written these biographical essays about.” And after a little resistance, I took that advice.

I had great support from my husband. I had great support from my sister and that gave me the courage to resign from ESPN and work on my book full time. And it really was an amazing experience. I put myself on a pretty religious schedule of rising at 4 a.m. and writing until 11:00 a.m. It was so great. My morning mind is lush so I was getting stuff done. And when I say writing from 4 to 11, it’s a combination of research and writing, and then it became a combination of research and refining. And then I finally finished, it was a battle at the end, but I’m finally finished and really it’s changed my life.

The book reads not only like an anthology, but also like a journey into Black history. Was that inevitable?

I don’t think that you can talk about culture without talking about the sociopolitical climate. And my book is very specifically about Black pop created by Black women. There’s so much ambition in the sound. ... I began to ask myself, “Where does this come from? Why is it so intense? Why is it so successful? Why is it so influential?” And one of the many things is that so many of the women were born into segregation. I wanted to know where that sound, that striving for bigness and perfection came from. And I think it comes from being treated unfairly, being treated with ugliness, being forced into a caste system.

In the case specifically of [singer] Marilyn McCoo, her [pregnant] mother used to take a train all the way up to New Jersey to go to a Black gynecologist there, wait till her infants were old enough to travel, and then go back down South where [McCoo] was raised. To me, that is just an incredible story not to know about a woman who has eight Grammys and influenced the culture as McCoo and The Fifth Dimension did. These are just the kind of details that are amazing to me that we just don’t know.

I had to write about the fact that Diana Ross’ family spent time struggling in the projects [in Detroit]. The benefits of the GI Bill were rarely if ever made available to Black soldiers returning home. So [Ross’ father] had to come back home and figure it out for himself, when the white veterans coming home were getting their college tuition paid for and receiving low interest loans to buy homes. But he had to be in the projects with his family, and that has an effect on Diana, as much as growing up listening to people like Dinah Washington and Billie Holiday had on her sound and her desire to become a Supreme. I mean, that’s a hell of a name. Even the Primettes [the group’s first name] is a hell of a name.

So that’s why it’s so important to have that kind of historical context. Music doesn’t just come out of nowhere. When we were in the fields, it came from the pain of all of that. So why wouldn’t the sound of Black pop come from something as well?

Terms such as “pop” and “diva” are used in a derisive fashion, but you use them with a sense of empowerment. How were you able to do that?

It’s super funny to me that when Black people achieve or arrive at some type of cultural destination, now that destination isn’t as cool or as wonderful as it was before Black artists arrived there. One of those spaces is the top of the pop charts. It was the ultimate thing that you could do outside of winning a Grammy in the music business, going No. 1, and then Motown started doing it with regularity. The Supremes battled the Beatles, and they were going punch for punch in the ’60s. And we see how much more the Beatles are uplifted than the Supremes are in our culture.

In the 1970s, you have disco. The spine of disco is Black women. And so it was immediately looked upon by even a lot of conservative Black mainstream figures as something less than, not as good as proper rhythm and blues, which is all disco is – it’s just rhythm and blues. It’s Black music. And then mainstream white artists looked upon disco as just a field from which to pluck inspiration and basically regurgitate it.

And then you get to the ’80s. And this is the one that really flipped because what Motown, and then disco, set up was the culture-shattering careers of Michael Jackson, Whitney Houston, Mariah Carey, and Lionel Richie, who achieved the kind of pop success that had never been achieved before. So then all of a sudden “pop” became a dirty word. Going pop was “whack” and you were “selling out.” So yes, I want to reclaim pop. ... It means being the most popular. Pop is the people’s choice and Black pop is the world.

I’m in the business of reclaiming that as I reclaim “diva,” as you mentioned, which is a whole thing that deserves its own book, honestly, but yes, reclaiming all of that, like stop calling stuff other than what it was. I’m fascinated by acceptance speeches and I need to find it, I was watching in real time when Carlos Santana … held [his] award up and said something to the effect of, “All of this is Black music and all of this comes from Africa.” So yes, I’m in the business of reclaiming Black women’s time.

How did you find a balance in your book between sorrow and solace? Or, as Maze might put it, “Joy and Pain”?

There’s a reason why many people consider that song to be one of Black America’s national anthems. It’s an emotional topic for me because music is such a great hiding place. You don’t have to hear the world. A lot of times, you don’t have to hear your own thoughts. Then you begin to allow yourself and the music to kind of become one. You have your favorites, what makes you feel better. You know, what gets you amped up. What saves your life. And then if you’re as lucky as I am, you become a super fan of the work itself, of what it takes to make music, and you let that inspire you over the course of your own life and inspire you to do your best work.

And I think I said in the introduction, where I would be in my life if not for music? I know so many Black people of my generation and Gen X who say they don’t know where they would be in their life without hip-hop. I’ve spent a career trying to explain, and I try to explain and shine bright. And I don’t know the degree to which I am successful in explaining what music really does for us, how it serves us and we serve it. But all I can continue to say is that it saves my life. So of course there’s joy and pain and there’s everything in it.

Is there anything or anyone else that you wanted to get in the book?

I wanted to get everybody in the book. The only way that I was able to finish the book was to limit it to the Black women in pop who have meant the most to me and my sister, who have meant the most to my mother and her sister, and who have meant the most to my grandmother and her sister. That’s the only way. And when I say meant the most to me, I mean the most to me professionally and personally, but there’s a zillion women. I would love to write a whole series of books just about Sade. It was hard not to write more about Aretha Franklin and as it is, her chapter and Whitney’s chapter is, like my editor called it, a book within a book. Oh my goodness. There’s not enough Mary J. Blige, not enough Ella Fitzgerald, Donna Summer, Linda Peaches from Peaches and Herb, Jody Watley, the list goes on.

How a minor league team got more followers than the Yankees

Even as baseball slips from its mantle as national pastime, the Savannah Bananas are reimagining it. It doesn’t matter if you win or lose, as long as everyone feels as if they belong at the game.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Even as baseball is in a slump, the Bananas, which field amateur players hoping to play in front of scouts, have 60,000 folks on their waiting list. And their antics are TikTok gold. Their cheerleaders: the dad-bod-glorious “Man-Nanas.” The dance troupe, the “Banana Nanas,” is made up of people over age 65. The team has over 3 million social media followers. That’s more than the Yankees. Did we mention they wear yellow kilts?

“Baseball is in a crisis, and it tells us about our society: We want a quick fix, fast action or entertainment,” says sports historian Thomas Zeiler, co-author of “National Pastime: U.S. History Through Baseball.” “And that really is what this Savannah team hit on: ‘Listen, this is baseball. But what we are really about is entertainment.’”

The team’s success can be traced back to what owner Jesse Cole’s father, Kerry, once told him: “Swing hard, in case you hit it.”

The rise of the Bananas as a social media phenomenon contrasts sharply with deeper woes with baseball writ large.

In that light, the team, some baseball historians say, is offering a return to a sandlot mentality. The club and its fans aren’t just a reminder of the game’s past. They may be a glimpse of its future.

How a minor league team got more followers than the Yankees

When Brian Nichols had a shot at hopping on the Savannah Bananas “world tour” this year, the guy known as the “Sexy Sax” didn’t hesitate.

As the musician traveled to far-flung locales like ... Alabama to showcase the team’s unique take on baseball – Banana Ball – he could hardly believe what he was seeing.

An obscure team from the Coastal Plain League was selling out other teams’ stadiums. And the crowds were going bananas.

“What kind of a sports team goes on a world tour?” says Mr. Nichols from behind golden Ray-Bans. “When we go into these stadiums where 200, 300 people usually show up and we sell it out, people notice. We’re modernizing baseball.”

OK, he’s partial. But the Bananas are truly in a league of their own. They are a team with appeal – and their own brass band.

Even as baseball is in a slump, the Bananas, which field amateur players hoping to play in front of scouts, have 60,000 folks on their waiting list. And their antics are TikTok gold. Their cheerleaders: the dad-bod-glorious “Man-Nanas.” The “Banana Nanas” are a dance troupe over age 65. The team has over 3 million social media followers. That’s more than the Yankees. Did we mention they wear yellow kilts?

“Baseball is in a crisis, and it tells us about our society: We want a quick fix, fast action, or entertainment,” says sports historian Thomas Zeiler, co-author of “National Pastime: U.S. History Through Baseball.” “And that really is what this Savannah team hit on: ‘Listen, this is baseball. But what we are really about is entertainment.’”

The team’s success since it launched in 2016 can be traced back to what owner Jesse Cole’s father, Kerry, once told him: “Swing hard, in case you hit it.”

The rise of the Bananas as a social media phenomenon is contrasting sharply with deeper woes with baseball writ large.

In that light, the team, some baseball historians say, is offering a return to a sandlot mentality. The club and its fans aren’t just a reminder of the game’s past. They may be a glimpse of its future.

“It’s great to see people thinking about putting the fans first and having it be an entertainment product where people can participate in a communal event for the night and go home with a smile on their face,” says Patrick Brown, a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C., and a lifelong baseball fan.

Today, the sport, critics contend, seems as confused as the rest of the country about where it is going.

Major League Baseball games are getting longer as at-bats drone on. Scoring is down. Players live in different ZIP codes from their fans. Advertisers appear happy as long as the TV shows folks in the stands behind home plate. The crickets in the rest of the stadium don’t seem to matter to the bottom line.

“‘We’re healthy, our revenue streams are up, but we know it’s no longer the national pastime,’” one MLB executive recently told Dr. Zeiler, a historian at the University of Colorado-Boulder.

University of Pittsburgh sports historian Rob Ruck predicts a “national sports recession” if fans keep decamping.

In that way, he says, the Bananas are starting to look like sandlot saviors.

“The Savannah team has tapped into the reaction [of] ... people who love sport for a lot of good reasons, but hate the business of sport,” says Dr. Ruck, author of “The Tropic of Baseball.” “It’s kind of a return to the past, which sounds like it would be a healthy antidote to what’s going on in the present.”

Mr. Cole, the 30-something owner who cites P.T. Barnum as an inspiration and wears a yellow tux, traces Bananaland to one moment: A 23-year-old coach of a minor-league team in the Carolinas, he sat bored in the dugout, waiting for the game to end so he could go home.

He wondered: Why can’t the game change? It turns out that many of his innovations fit a tradition in early baseball of regional rules. Among them: Games have a two-hour time limit, fans can catch fly balls for outs, and players can steal first base. At the same time, the Bananas are thoroughly tuned to a TikTok world.

“The Bananas are doing the best of both: They are getting the spontaneity and joy and ragtagness of early baseball with the modern sense of time,” which is far faster than when the game was invented before the Civil War, says Sarah Gronningsater, a historian at the University of Pennsylvania.

Dr. Gronningsater says the Bananas were first brought to her attention in her history of baseball class by a British student who spotted the team on TikTok.

The seeming spontaneity on the field is intended to create moments. But each game is carefully scripted, says Mr. Cole. Miscues, misfires, and mistakes are valued as much as when things go right. Players and staff are encouraged to be themselves – just to the power of 10.

There’s a dancing first-base coach who admittedly knows more about backflips than baseball. Meanwhile, the janitor became one of the dugout coaches during last year’s championship season. There’s the slowest race in the world: crawling toddlers! Concessions are included as part of the ticket. Grayson Stadium, where Jackie Robinson once played and Babe Ruth hit a home run, is free of ads and billboards. Instead, there’s a Fan Wall, covered with fan signatures.

They are also Coastal Plain League champions who spit-roasted the Holly Springs Salamanders 9-2 on Tuesday night, with Bananas players splitting at-bats with choreographed shimmying contests with local dancers.

The Salamanders looked helplessly on from a scrum of folding chairs that served as their dugout. It can’t help but raise comparisons to another team famous for its flair, athleticism, and globetrotting ways.

“Like at a [Harlem] Globetrotters game, you almost feel bad for the other team,” says Dr. Zeiler.

“You feel lucky just to get a ticket,” says Vik Manocha, a college student who grew up on nearby Wilmington Island. “There’s just a buzz about a team that’s really trying to change baseball.”

However, not every one in the stand prizes showmanship over sportsmanship. A lifelong baseball fan, Jim Joyce remembers going to Savannah Redlegs games in the mid-1950s with his father.

“I can only muster up energy to come to one game a year, and, look at me, I’m leaving after the fifth inning,” says Mr. Joyce. “It’s something, but it isn’t baseball.”

“I agree baseball needs reform,” he adds. “I’d accept a pitching clock [to speed up at-bats]. Can’t a guy just hope for a happy medium?”

Not that night. Behind him, an entire stadium can be heard singing along to Coldplay’s “Yellow,” cellphone lamps lit.

“’Cause you were all yellow,” the crowd booms.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Italian pride in a leader’s humility

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Elected leaders face a profusion of mega-pressure points these days – inflation, heat waves, high debt, or the pandemic. Many governments have fallen, as in Bulgaria, Britain, and Israel. Others are faltering, as in Ecuador and the United States with President Joe Biden. In Italy, a country notorious for its rapid turnover of prime ministers, the government of Mario Draghi appears to be on the brink of collapse after 17 months of rare unity. Yet a compelling counterforce could keep him in power.

Last Thursday, the prime minister offered to quit after splits emerged in his cross-party coalition. President Sergio Mattarella wisely refused the resignation. That gave enough time for an upwelling of support for Mr. Draghi and his unusual style of consensus leadership in a nation rife with fractious politics.

Hundreds of mayors signed a petition backing him. Many industrialists and unionists joined the chorus. European leaders also weighed in. Mr. Draghi stands out in Italy because of his humility and tendency to ask questions first. He displays a willingness to listen hard in order to find common ground.

Amid so many crises in democracies, Mr. Draghi offers a lesson in stability, innovation, and competence.

Italian pride in a leader’s humility

Elected leaders face a profusion of mega-pressure points these days – inflation, heat waves, high debt, or the pandemic. Many governments have fallen, as in Bulgaria, Britain, and Israel. Others are faltering, as in Ecuador and the United States with President Joe Biden. In Italy, a country notorious for its rapid turnover of prime ministers, the government of Mario Draghi appears to be on the brink of collapse after 17 months of rare unity. Yet a compelling counterforce could keep him in power.

Last Thursday, the prime minister offered to quit after splits emerged in his cross-party coalition. President Sergio Mattarella wisely refused the resignation. That gave enough time for an upwelling of support for Mr. Draghi and his unusual style of consensus leadership in a nation rife with fractious politics.

Hundreds of mayors signed a petition backing him. Many industrialists and unionists joined the chorus. European leaders also weighed in. Mr. Draghi, a U.S.-trained economist and former head of the European Central Bank, had earned a reputation for saving the euro currency during a crisis a decade ago. In addition, the European Union cannot afford a crisis in the eurozone’s third-largest economy.

Mr. Draghi stands out in Italy because of his humility and tendency to ask questions first. He displays a willingness to listen hard in order to find common ground. Those qualities are especially needed in his drive to pass reforms mandated by the EU to receive pandemic-related subsidies.

Opponents find it difficult to pin down his political views. “My personal destiny matters absolutely not at all,” he said last year. But he is always open and transparent about the range of potential solutions, a quality of leadership that was necessary when he led Europe out of its financial crisis.

His coalition of “national unity” may fall someday or he may decide to simply retire. For now, amid so many crises in world democracies, Mr. Draghi offers a lesson in stability, innovation, and competence. Italy seems to appreciate that for now.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Let God direct your giving

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Karyn Mandan

When our efforts to help others are motivated by a desire to bear witness to God’s goodness, they naturally become more joyful and renewing, rather than overwhelming and frustrating.

Let God direct your giving

Many people today feel stressed and put upon. Parents, teachers, caregivers and others feel drained. They’re giving time, but too often not finding joy in the giving.

At one point in my life, giving of myself to friends who needed help frequently became a joyless burden, summoning up feelings of being used. But things turned around when I learned how to listen first to what God was telling me to do.

One day I woke up with that “here we go again” feeling. I’d offered to help a friend, and I already felt overextended before even getting out of bed! Why did I keep doing this? Being the ideal friend seemed to mean jumping in to fill someone’s need and never disappointing anyone. I felt responsible for everyone else’s well-being. But to “rescue” them often involved doing the work that was actually theirs to do – and in the process sacrificing my time, energy, and joy.

I found encouragement, though, in a message of the Bible: that no one is deficient. This includes us and anyone we may be helping. We abound with the good freely given to us by God. Made in the image of the one infinite divine Mind, we’re each the brilliant and completely spiritual expression of God. We naturally manifest such God-given qualities as wisdom, creativity, strength, purpose, and joy. And the divine intelligence that endows us also provides the opportunities to put these qualities to use – for our benefit and that of others.

Christ Jesus was the supreme example of giving to others out of his God-given spiritual capacities – healing and providing for others. He referred to the “burden” he carried as light, and he invited us to carry it, too: “Come to me, all of you who are weary and over-burdened, and I will give you rest! Put on my yoke and learn from me. For I am gentle and humble in heart and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy and my burden is light” (Matthew 11:28-30, J.B. Phillips New Testament).

Jesus wasn’t personally responsible for other people. But he did take responsibility for how he saw them. Looking beyond apparent brokenness and deprivation, he found – and proved – God’s inexhaustible gift of health and strength, always present and working on behalf of everyone.

In my situation, this was the breakthrough. I realized that there was a difference between being responsible for everyone else and taking responsibility for how I saw them. One is sometimes joy-less, the other is joy-full!

The concept that we are man-made and self-made is a limited, material view of creation. It highlights lack that needs to be materially compensated for. But we all have a God-given ability to spiritually discern what God has put in place – abundant good – and to enjoy its benefits!

I decided to rely on this spiritual sense to guide me. Whenever there was an opportunity to give of myself, I first asked, “Why am I giving?” And through prayer, the answer became less about the need to feel appreciated by others, and more about seeing others as God sees them – whole and fulfilled. It was about being in a position to bear witness to their spiritual manifestation of God-created perfection. And I realized that was enough.

With this shift in motive, I felt free to step up and joyfully volunteer. And when something didn’t feel as though it was mine to do, I could decline without feeling I’d let someone down. Doing right by God has sustained me in every decision. Learning how to be a truly good friend – loving unselfishly and without expectation of anything in return – has revealed what I actually needed: a clearer sense of who I am, who everyone is, as God’s capable, joy-filled, spiritual offspring.

Mary Baker Eddy, who established the Monitor to benefit humanity, wrote in her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “Giving does not impoverish us in the service of our Maker, neither does withholding enrich us” (p. 79). Getting clear and unambiguous about the one relationship – the direct relation we all have to our infinite source, God – and seeing others as God sees them leads to selfless, joyful expression. Following divine guidance in giving to others nourishes, inspires, and renews us.

The New Testament in Modern English by J.B. Phillips copyright © 1960, 1972 J.B. Phillips. Administered by The Archbishops’ Council of the Church of England. Used by permission.

A message of love

Cooling off

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Tomorrow, come back for a look at a peanut paste product, long known as “Plumpy’Nut,” that has played a key role in reducing child malnutrition in Africa. Now, its reach is being tested by a disrupted supply chain and spiking ingredient prices due to the war in Ukraine.