- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Electoral Count Act: Can reform protect democracy?

First the bad news: Evidence presented by the Jan. 6 committee has shown how former President Donald Trump and his allies tried to manipulate current laws to disrupt the presidential election process.

Now some good news: There’s a serious effort underway in Congress to fix holes in one crucial statute to try and deter such an attempt from happening again.

At issue is the Electoral Count Act, a rickety antique passed in 1887 that governs the official counting of Electoral College votes and the naming of the president-elect. It’s poorly written and vague in important spots.

On Wednesday, a bipartisan group of senators proposed a package of new legislation to modernize the 135-year-old law.

The bills would tighten existing wording to help ensure that each state submits only one conclusive slate of Electoral College electors. No fake slates of self-designated “electors,” as Trump allies produced following the 2020 vote.

They would state that the role of the vice president is “solely ministerial” when counting electoral votes. That would write into direct language the conclusion that many electoral scholars – and former Vice President Mike Pence – have already reached.

The legislation would also make it more difficult for members of Congress to object to a state’s electors – and more difficult for state legislators to override their state’s popular vote.

Some experts don’t agree with everything the package proposes. They worry the fixes might close some holes and open new ones. The Jan. 6 committee has notably said it is considering its own Electoral Count Act reforms.

A compromise might well emerge here. For now, the existing effort is at least a “massive improvement” over the status quo, according to Matthew Seligman, a Yale Law School fellow who’s studied the issue for years.

“I think it’s our last best hope,” he tweeted this week.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Jan. 6 summer hearings wrap up: What did we learn?

After eight hearings, the basic outline of what took place in the run-up to and on Jan. 6 remains the same. But new details could serve to sharpen a case against the former president.

The Jan. 6 House select committee wrapped up the last of eight summer hearings Thursday night, in which it sought to demonstrate that former President Donald Trump bears responsibility for the attack on the U.S. Capitol.

If one thinks of this investigation as a connect-the-dots puzzle, the outline was already known before the committee began its work. But they put forward many more dots – via hundreds of interviews and 140,000 documents gathered – in an attempt to present a sharper final picture of presidential culpability.

Over the course of six weeks, the committee sought to prove that Mr. Trump is unfit for public office, and that he willfully deceived his supporters in a desperate bid to stay in power.

Legal scholars disagree on whether the evidence could lead to criminal charges against the former president. Still, many say the hearings have provided a valuable public record.

“These are very disturbing and at times breathtaking accounts,” says Jonathan Turley, a constitutional law professor at George Washington University who has been critical of the committee’s lack of GOP-appointed members and robust questioning. “The evidence ranges from the horrific to the heroic.”

Jan. 6 summer hearings wrap up: What did we learn?

It was the season finale, if not the end of the series. Last night, the Jan. 6 House select committee wrapped up the last of eight summer hearings, in which they sought to demonstrate that former President Donald Trump bears responsibility for the attack on the U.S. Capitol.

The final hearing focused directly on what Mr. Trump was doing for the 187 minutes between when the Capitol was breached and when he released a video from the Rose Garden urging rioters to go home.

If one thinks of this congressional investigation as a connect-the-dots puzzle, the basic outline was already known before the select committee began its work. But the committee put forward many more dots – via hundreds of witness interviews and 140,000 documents gathered – in an attempt to present a sharper final picture of presidential culpability.

Over the course of six weeks, the committee sought to prove that Mr. Trump, who is widely expected to announce a 2024 presidential run, is unfit for public office, and that he willfully deceived his supporters about his electoral defeat in a desperate bid to stay in power.

“He is preying on their patriotism,” said Vice Chair Liz Cheney, a Wyoming Republican, in her closing statement of the prime-time hearing. “On Jan. 6, Donald Trump turned their love of country into a weapon against our Capitol and our Constitution.”

The committee also suggested Mr. Trump might bear criminal responsibility, though legal scholars disagree on whether the evidence presented by the panel warrants bringing charges against the former president. Some now see a strong case against Mr. Trump, potentially for multiple crimes, ranging from defrauding the public to assisting an insurrection. Those charges could be further bolstered by the countless hours of depositions not yet released, which may include additional relevant details.

“Either he realized he lost or deliberately hid the truth from himself. And then he proceeded to do everything that he could possibly do without any regard for harm to other people, or to the country, without any regard to the law in order to overturn the election,” says Laurence Tribe, a professor emeritus of constitutional law at Harvard University. “All of this adds up to very serious federal crimes.”

Others say that while the hearings have exposed reprehensible, even immoral, behavior on the part of the former president, they fell short of establishing criminal culpability.

“A president’s failure to ‘do the right thing,’ – and that’s a direct quote from the committee – is a political rather than criminal judgment,” says Jonathan Turley, a constitutional law professor at George Washington University who has been critical of the committee’s lack of GOP-appointed members and robust questioning.

Still, while he doesn’t see a strong legal case against Mr. Trump, he says the hearings have played a valuable role in creating a comprehensive record of the events leading up to Jan. 6 and the attack on the Capitol.

“The committee has contributed a great deal in making details and accounts public,” says Professor Turley. “These are very disturbing and at times breathtaking accounts. The evidence ranges from the horrific to the heroic.”

Many of the hearings included graphic images of the violence of that day, scenes which were often difficult to watch. Several police officers who had battled the crowds at the Capitol attended the hearings in person and at various times could be seen with their heads in their hands. At the conclusion of most hearings, the committee members would file off the dais to shake hands with – or in many instances embrace – the witnesses, thanking them for sharing their stories.

Last night, Representative Cheney praised the witnesses who had been willing to come forward, including Cassidy Hutchinson, the young aide to former White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows. “She knew all along that she would be attacked by President Trump and by the 50-, 60-, and 70-year-old men who hide themselves behind executive privilege,” she said. “But like our witnesses today, she has courage, and she did it anyway.”

Outlines now filled in

The broad contours of Mr. Trump’s rhetoric and actions leading up to Jan. 6 have been known for more than a year. Amid a rapid scaling up of mail-in voting during the pandemic, he began questioning the validity of the 2020 election results before voting even started. Then he persisted in falsely claiming that he had won, even after all but one of the 62 lawsuits his team brought had failed or been thrown out. He pressured the Department of Justice to find evidence of fraud, and when Attorney General Bill Barr said there was none on a scale to overturn the election, the president turned to state election officials, who likewise did not find any such evidence.

Then, in what many saw as a last-ditch and unconstitutional attempt, he tried pressuring state legislators to nominate alternative slates of electors. The idea was that when Congress met on Jan. 6 to count the Electoral College votes, a process overseen by Vice President Mike Pence, they could delay or overturn Joe Biden’s victory. When Mr. Pence made clear that morning that he did not believe he had the constitutional authority to unilaterally accept or reject the electoral votes, Mr. Trump encouraged the massive crowd rallying near the White House to march to the Capitol. As rioters breached the building and engaged with law enforcement, he did nothing to stop the violence for hours.

The committee filled in new details within that narrative arc, bringing Republican lawyers, state election officials, and state legislators to testify in person, as well as former White House officials. Together with selected clips of videotaped depositions of former Trump aides, the committee outlined a pattern of behavior that they say demonstrated Mr. Trump willfully deceived his supporters into believing the election was stolen, and deliberately sent angry protesters, some of whom he knew to be armed, to disrupt the proceedings at the Capitol and pressure Mr. Pence and members of Congress as they began counting the Electoral College votes.

Monitor Backstory: Covering Jan. 6

What happened on Jan. 6, 2021, at the U.S. Capitol? The answers are shaded by deeply held perspectives. How can a journalist cover such an event and its fallout without being prejudicial? The Monitor’s Christa Case Bryant speaks with host Samantha Laine Perfas about the sense of fairness that guides her reporting work, and how that helps define the Monitor’s approach.

Some of the most attention-grabbing details of the eight hearings came from Ms. Hutchinson, the White House aide, who testified that Mr. Trump was told some of the protesters were armed but had nevertheless asked the Secret Service to let them into his rally, saying they weren’t there to hurt him. She also related an account she’d been told by another official, that when Mr. Trump was informed he could not join the protesters at the Capitol, he tried to grab the steering wheel of the presidential vehicle and lunged for the neck of a Secret Service agent – an account that both Mr. Trump and, reportedly, Secret Service agents have denied. And she testified that when the president was told some rioters were yelling, “Hang Mike Pence,” Mr. Trump said he thought the vice president deserved it – something she pieced together from two conversations she had heard.

Last night’s testimony included an audio clip, distorted for security reasons, of someone identified only as a “White House security official,” who said that Secret Service agents in the Capitol on Jan. 6 became afraid for their lives, relaying goodbyes to their families, and warning that they might need to use lethal force to protect Mr. Pence.

Diverging views

While only two of the committee’s nine members are Republicans, and both are outspoken critics of Mr. Trump, nearly all of the testimony was given by Republicans who had supported or worked for the former president. Still, many Trump supporters have criticized the highly scripted nature of the hearings and lack of cross-examination to explore other possible motives or interpretations, or to evaluate the accuracy of witnesses’ recollections of an intense day more than 18 months ago.

Ms. Cheney addressed those criticisms in her remarks last night. “Do you really think that Bill Barr is such a delicate flower that he would wilt under cross-examination?” she asked, and then went through a list of other members of Mr. Trump’s inner circle who had testified. “Of course not. None of these witnesses are.”

Professor Tribe – who once taught two committee members, Reps. Adam Schiff and Jamie Raskin, and is friends with both – says the hearings have provided stronger evidence than the impeachment proceedings on whether Mr. Trump incited an insurrection. He says it could now be “quite easily proven” that the former president defrauded the American people and obstructed a congressional proceeding. He even sees a pathway for prosecuting more serious crimes, including engaging in and assisting an insurrection against the authority of the United States, which would render Mr. Trump ineligible to ever hold office again, as well as seditious conspiracy, punishable by 20 years in prison.

Professor Turley disagrees, expressing skepticism that any of the crimes enumerated by Professor Tribe could be proven in court. He notes, for example, that the District of Columbia’s attorney general already investigated Mr. Trump for insurrection and never brought charges.

“The committee members said at the outset that they had uncovered what Representative Schiff called compelling evidence of criminal conduct by President Trump,” he says. “We have yet to see that evidence materialize.”

One question to consider is what else the Jan. 6 committee may have gleaned from witness depositions that it chose not to include in the tightly focused presentations to the nation.

“What was on TV was for the general public – not for a judge or for legal experts. And therefore, it’s understandable that they tried not to spend too much time on details that might matter in court,” says Ilya Somin, a professor at George Mason University in Virginia who researches constitutional law. “I would guess that many of those kinds of things were in fact asked about in the depositions.”

A deeper look

Merch, tours, hope: Inside the modern economics of a rock band

Musicians are revered for their creativity and artistic skill. But in the current economic climate and music scene, “making it” has as much to do with perseverance as musicianship.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 15 Min. )

While never flashy, there used to be a well-trodden path for less-than-famous rock bands, a middle tier of fame and fortune that could support a middle-class lifestyle: Go on tour, sell records. Mostly sell records, though. But in today’s age of music streaming, the digital-only economy rewards the biggest acts.

Without people paying for albums, a new emphasis has been put on tours and merchandise sales – and finding so-called super fans who will pay for anything and everything, from music to monthly Patreon subscriptions.

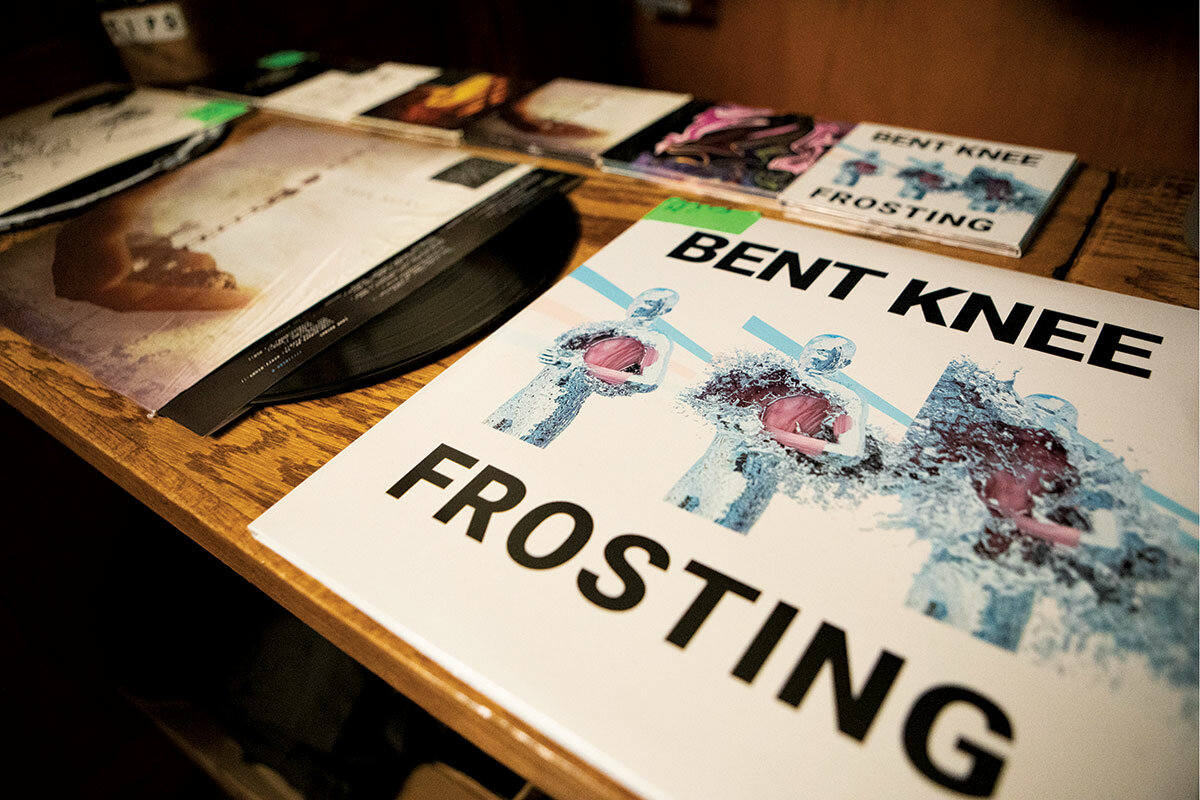

Our staff writer went on tour with Bent Knee, a rock band from Boston that is intimately familiar with the new strains put on musicians. After years of shoestring tours, the trip was the last one for bassist Jessica Kion and her husband, guitarist Ben Levin.

The remaining four musicians of Bent Knee will continue to play on. Through a combination of playing shows and doing side gigs, the musicians are doing OK. Multi-instrumentalist and producer Vince Welch just purchased a home with his wife, singer and keyboardist Courtney Swain. If anything, this short summer tour demonstrated that the benefits can still outweigh the hardships, even amid the changed financial landscape.

“We came out for this supershort tour that wasn’t publicized hard ... and everyone walked home with a decent paycheck and had a great time,” says violinist Chris Baum. “There’s a lot of optimism right there.”

Merch, tours, hope: Inside the modern economics of a rock band

On a stretch of highway under construction near Chicago’s downtown skyscrapers, horns blare in standstill traffic. As seven lanes of cars funnel into one, a black van inches along in the 90-degree heat. The van’s occupants have just finished work and are now slumped in their seats. Rush hour? No, it’s half-past midnight.

Ninety minutes earlier, the four men and two women had finished entertaining roughly 120 people who came to hear their rock band, Bent Knee, play a small, sweaty venue named Schubas Tavern. It was the latest stop in a nine-date tour, their first as headliners since the pandemic upended the live arts world.

Over a decade of touring, Bent Knee has endured plenty of scrapes on the road. There was the time in 2018 they drove through a blizzard in Wyoming. Their van skidded off the road on black ice and flipped onto its side.

“It took five seconds,” recalls multi-instrumentalist and producer Vince Welch.

“The two scariest details that stick with me are, one, the fact that I couldn’t open the driver’s side door because the wind was so strong,” says lanky guitarist Ben Levin. “The other chilling detail is that Jessica was hanging from her seat belt. Vince had to physically ...”

“Catch me,” finishes bassist Jessica Kion.

Mr. Levin and Ms. Kion are married. Onstage they’re a goofy duo, playfully hip-bumping each other. For once, Mr. Levin isn’t smiling. He can’t forget their near miss in Wyoming and the reason they kept driving in a whiteout, not willing to pull over for a night.

“This emphasis that you just can’t miss the gig, because if you miss a gig it’s a huge cost liability – that almost killed us,” he says.

Every night across America, countless bands operating on a shoestring budget abide by the ethos that the show must go on. They can’t afford to do otherwise. These musicians are the original gig workers. Bent Knee realizes that it’s not likely to be on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine or on a Marvel movie soundtrack. Its goal is more modest: to make a living wage as musicians by building a robust fan base that is willing to pay to hear its music and see it play.

This used to be a well-trodden path for rock bands, a middle tier of fame and fortune that could support a middle-class lifestyle. Today it’s harder than ever to break out of obscurity. Simply put, the digital economy rewards the biggest acts, leaving the rest to chase the crumbs.

“You have two economies in the music industry now,” says Andrew Leff, a professor at the University of Southern California’s Thornton School of Music in Los Angeles, who used to manage rock bands. “You have the economy which I’ll call Big Music, which is the 1%, and then you have the 99% of everybody else, which Bent Knee is part of. And the industry doesn’t care about the other 99% anymore, which is why groups like Bent Knee are doomed. And I say that not out of cynicism because, listen, I love Bent Knee.”

Bent Knee doesn’t make it easy on itself. Its genre-bending art rock is hard to label – and to market to the masses. But underappreciated, idiosyncratic acts have historically lit the creative bonfires that rejuvenate the mainstream music industry, from disco to grunge and beyond.

To get this far, Bent Knee has squared its shoulders against the doubters, found alternate sources of income, and dug into deep reserves of grit. The question is whether this is enough to ride out the post-pandemic uncertainty and keep the band going.

“I think a big theme for the band for many years is just to persevere,” says the band’s singer and keyboardist Courtney Swain. “It’s a big bond that we’ve formed through that.”

The morning after the Chicago show, the band hits the road for Pontiac, Michigan. Sound check is at 4:30 p.m.

The van hurtles down Interstate 94 beneath an oceanic sky dotted with small archipelagoes of clouds. On the sides of the highway, strips of peeled tires look like rubber roadkill. Turkey vultures swirl above billboards in which smiling attorneys promise bonanza payouts for injury lawsuits.

The band only stops once to fill the van’s tank. Unfurling themselves from the vehicle, the musicians head to the bathroom. Inside the gas station, the lunch options range from fossilized doughnuts to hot dogs that have been tanned orange from sitting under heat lamps.

Yes, it’s every bit as romantic as it sounds. But for violinist Chris Baum, it’s life on the open road – and he loves it. “I’ve seen more of the world than most people will in their lifetimes,” he says.

“I like the ‘being in-motion,’” says Ms. Swain, who grew up in Japan and is now married to Mr. Welch, the multi-instrumentalist.

The singer co-founded Bent Knee with Mr. Levin in 2009 while they were both students at Berklee College of Music in Boston. The band’s name is a playful portmanteau of their first names: Ben and (Cour)tney. Mr. Levin, gregarious by nature, recruited the other members in the college cafeteria.

As the six musicians holed up together to write songs, they became a mutual support group. Each began to share formative experiences. Gavin Wallace-Ailsworth had grappled with depression. Mr. Baum lost his father fairly young. Mr. Levin endured summer camps that he likens to “Lord of the Flies.”

The band that emerged from these sessions shares a quirky sense of humor; they played with bags over their heads on a recent livestreamed show. Their diverse musical influences - Kiss, Fiona Apple, Kendrick Lamar, Nine Inch Nails – go into a blender that produces songs like “Queer Gods,” a 2021 release in which sugary auto-tuned pop is backed by heavily distorted mariachi horns. By contrast, a song like “Bone Rage” is powered by defibrillator jolts of guitar, a glitchy high-hat rhythm, and operatic interludes. Predictability isn’t their strong suit.

Bent Knee’s big break came in 2016 when a subsidiary of Sony Music signed Bent Knee for two albums. The Wall Street Journal and The Boston Globe wrote features about the group. Bigger bands asked it to tour as their support act.

Going out on the road is what rock ’n’ roll is all about. For decades, musicians went on tour in the United States and overseas to promote their latest albums, but most of their income came not from concerts but from vinyl and then CD sales. That was the business model.

But once music became digitized, first as downloads and then as streams, people started paying less for it. It was easy to share digital files. It was also easy to pirate music. Today millions of people subscribe to streaming platforms like Spotify; millions more simply listen for free on YouTube and other digital platforms.

Artists like Drake with millions of followers can rake in big money from licensing tracks to streaming platforms. But a single stream is worth peanuts: roughly $0.0038, according to the Union of Musicians and Allied Workers. Bent Knee has only one song that has been played more than 1 million streams on Spotify, which adds up to $3,800.

And that’s not even their paycheck: Spotify pays out to the song’s copyright owner, typically a record label. “The label takes 85% of that money and most artists are still on a 15% royalty, which was low even back in the physical [media] era,” says Mr. Leff, who used to manage Living Colour and King Crimson.

For most artists, touring is now the only viable path to making a living. Big names typically charge hundreds of dollars per ticket. For acts like Bent Knee, though, tickets cost $15 each. After promoters and venues take their cut, there’s not much left for six band members and a manager, which is why Bent Knee always brings boxes of T-shirts and records to sell to fans at concerts.

Odd as it sounds, band merchandise is what can make touring profitable. Still, there are only so many T-shirts you can sell at $40 a pop, which is why members of Bent Knee aren’t going to buy mansions with guitar-shaped swimming pools anytime soon.

The Pontiac show is on the second floor of a venue called The Crofoot in the heart of what feels like a ghost town. In 2009, General Motors shuttered its manufacturing plant here. Empty storefronts look as if they’ve been closed for decades. Towering overhead, a high-rise art deco building seems as lonely as a decommissioned lighthouse.

The motels and hotels where Bent Knee stays aren’t glamorous either. But a two-star Midwestern hotel with the euphemistic description of “unpretentious” sure beats the punk flophouses where it stayed in its early years.

“We slept in some janky places,” says Mr. Welch, who plays keyboards and also uses a laptop to spontaneously create sound designs onstage. “I’m pretty sure I would not be able to continue to tour like we were touring at the beginning.”

As prices rise, budgeting for multicity tours – van rental, insurance, hotels, and meals – gets tougher. Gas alone for this tour is likely to top $1,000. At least this time Bent Knee is the main act. It’s also done tours as support acts to other bands, which earn an even smaller cut since the idea is to gain exposure to new fans.

When the six musicians studied at Berklee, the importance of finding alternate revenue-making ventures was drilled into them.

Most employers won’t give full-time workers a month off to go on tour every year, says Mr. Levin. He hasn’t had a day job in years, or the regular salary that comes with it. Five years ago, he had to wear broken glasses with a rubber band holding the damaged lens in its frame.

Today he has over 150,000 subscribers to his channel on YouTube, which he parlays into online guitar courses that can net him $150 per hour. Mr. Baum is a session violinist. Mr. Wallace-Ailsworth, who has been profiled in Modern Drummer magazine, teaches music lessons over Zoom. And Ms. Swain plays keyboards in musical theater productions in Providence, Rhode Island, where she lives with Mr. Welch, who moonlights as a driver for a ride-hailing service.

A few years ago, Ms. Swain talked with her therapist about the stress of living on her erratic musician’s income.

“She gave me this printout, which was called a values worksheet, and on it was just all of these values about, like, I want to be part of a community; I want to be financially viable; I want to find meaning in my work; I want to have friends; I want to love somebody,” recalls the singer. “What that did for me was that I realized that I’m really successful and happy in the sense that I’m fulfilling a lot of my values.”

Ms. Swain says that although she wants people to hear her music, she’s making it for herself. But like virtually all performers, she enjoys the validation and morale boost she gets from an appreciative live audience.

That night in Pontiac, Ms. Swain’s voice swoops, dips, and glides through several octaves as effortlessly as the turn of a dial. The audience is smaller than in Chicago, but it’s a more energetic show. For a rock song called “Lovemenot,” Ms. Swain’s voice takes on a gnarly tone. During the crunchy guitar riff, Mr. Levin and Ms. Kion are bouncing up and down. Mr. Baum’s fringe hangs low as his frenzied bowing arm seesaws on the violin. The audience heaves like storm-tossed waves that are trying to batter against the stage. Ms. Swain shakes her long hair. She’s beaming.

Bent Knee is a big believer in a business model called 1,000 True Fans. In 2008, Wired magazine writer Kevin Kelly published an essay that posited the idea that if you can find a thousand “true fans” who “will purchase anything and everything you produce,” you can carve out a sustainable career in the arts.

It’s an idea that speaks to a strain of Silicon Valley techno-utopianism, a counterweight to the network effect of tech platforms and their winner-take-all culture. And it would seem to favor acts like Bent Knee that are far from blockbuster status. The band members are active on digital platforms that exist to facilitate that sort of connection between artist and fans. These include Bandcamp, a streaming and merchandise sales site for musicians; the crowdfunding site Kickstarter; and the subscription patronage service Patreon. Ms. Swain says that one fan used to pay her $100 per month via her personal Patreon page.

But some in the music industry are skeptical about how many struggling artists have actually managed to find their true fans who pay them $10 a month. One thousand doesn’t sound like a lot. But first you have to find them.

George Howard, a music industry veteran and professor at Berklee, reckons that a band would need to get its music in front of about half a million fans since only a sliver of them will qualify as hardcore enthusiasts. The kind of fan who will hand over their credit card details for recurring monthly payments.

“As they sort of cascade down to that funnel, most of them are like, ‘Yeah, I like this band OK, but there’s no way I’m adding to my Hulu bill, my Netflix bill, my whatever bill,’” says Mr. Howard, who co-founded a digital marketing firm and is a director of TuneCore, an independent music distributor.

Mr. Howard says that streaming platforms have data that can pinpoint “true fans,” but they don’t share that information with artists. He argues that blockchain technology, which powers cryptocurrencies, could eventually help bands get access to that information.

For now, Bent Knee is trying to deepen the connections with the fans that reach out to it.

On this tour, a pair of devotees who’d just graduated from high school flew from Florida to Cleveland to catch a show. One follower from Ohio is attending every show. Another admirer buys the band dinner every time they visit Michigan and has hosted them overnight at his home.

“They have an interesting rapport with fans that I haven’t seen with a lot of bands where they know, like, a lot of people’s names,” says Anthony Gesa, Bent Knee’s manager. “The band cares about the people who care about them.”

The fans, in turn, become evangelists. Lia Corrales, an astronomy professor, was introduced to Bent Knee by a friend in 2017. After the gig in Pontiac, her fifth Bent Knee show, she explains that she name-checks the band on her profile on dating apps. “For a long time when I was dating and on OkCupid, I would mention this band. I literally got people messaging me who were not good matches, but just saying, ‘Thank you for introducing me to this band.’”

When the Pontiac show is over, the band members chat with fans and autograph records. Ms. Kion is still buzzing from the energy of the gig. But her husband is in a more reflective mood. Before the show, he’d called his parents, who were in Boston pet-sitting the couple’s new dog, Rose. When the pit bull heard his voice over the speakerphone, she began to bark.

“It broke my heart,” says the guitarist. “I’ve got to get back to Rose.”

It’s not just the dog, though. And not just about Mr. Levin’s pensive mood in Pontiac. The guitar-and-bassist couple have already decided – call it a pandemic epiphany – that they’ve had enough of life on the road. And so, this is their last tour with Bent Knee.

“I used to be made for this,” says Mr. Levin. “I used to drive, like, 17 hours in a row, and I’d be like, ‘Yeah!’”

“Twenty-two [hours] is your record,” Ms. Kion says to her husband.

“My belief was there was a magic to travel,” says the guitarist. “Life happens, and you change.”

The duo broke the news to the others before the tour started. Each night onstage, Ms. Swain and Mr. Baum each pay tribute to the guitarist and bassist. There are visible lumps in throats.

The remaining four musicians plan to reconvene for a songwriting session in the fall. It will be an opportunity for Bent Knee, minus two original members, to once again reinvent its sound. It also plans to continue touring. Through a combination of playing shows and doing side gigs, the musicians are doing OK. Mr. Welch and Ms. Swain just purchased a home. If anything, this short summer tour demonstrated that the benefits can still outweigh the hardships.

“The band really hasn’t been active for the length of the pandemic, and we came out for this supershort tour that wasn’t publicized hard ... and everyone walked home with a decent paycheck and had a great time,” says Mr. Baum in a phone call a few days after the last date in New Jersey. “There’s a lot of optimism right there.”

Mr. Levin is still going to be making music, both solo and with his wife and other collaborators. He’s not going to miss all the hours in limbo in the back of the van or arriving at motels at 2 a.m. where his bedroom is flooded with water.

But when he thinks back to the final tour with Bent Knee, that’s not where his mind drifts. What he remembers is a brass marching band on a field in Michigan.

It’s the morning after the Pontiac concert, and the band has driven two hours outside Detroit to Adrian College, a liberal arts college. When it arrives, the college’s football field is a hive of activity, filled by more than 100 shirtless drummers and trumpet, bugle, and French horn players who make up The Cavaliers Drum & Bugle Corps. They’re rehearsing a production titled “Signs of the Times” that they are set to perform in an international championship in Indianapolis on Aug. 3. It features adaptations of pieces by Bach, the Steve Miller Band, Harry Styles – and Bent Knee.

Sitting in a press box in the stands, members of Bent Knee mouth “wow” to each other as The Cavaliers play a rendition of their song “The Floor Is Lava.” The players’ polished brass instruments gleam like mirrors. The sound blast is immense. Coaches in the stands choreograph the movement of the men on the field as they shift from one formation to the next.

During a rehearsal break, one of the coaches invites the band onto the field. Kevin LeBeouf is a Bent Knee fan – he was at the show the night before – and he had the idea of adapting four Bent Knee songs for brass instrumentation. He’s thrilled that they’ve come to the rehearsal. The Cavaliers form a ring around the band members, who sit on the 50-yard line, and Mr. LeBeouf conducts a rendition of another song, “Way Too Long.”

Afterward, The Cavaliers cheer for the band whose music they’ve played. Each member of Bent Knee is grinning; Ms. Kion looks teary. “It felt like one of our songs was used in a movie that was amazing, in a scene that perfectly fit,” she says later.

Mr. Levin stands up to address the assembled corps. He’s been thinking about what it means to quit Bent Knee and how music it’s created can take on a new life beyond the band.

“For me, this is like a bone-vibrating, soul-nourishing gift that I’ll never forget,” he says. “Maybe the closest you could ever imagine to being in the audience’s shoes after 12 years of doing this.”

A letter to

The meaning of Mandela, explained by a mother

The Monitor’s Africa Editor, a Nigerian married to a white South African, reflects in a letter to her children on the meaning of Mandela Day. Promoted as a call to charity, it would be better spent as a celebration of Mandela’s vision, she says.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

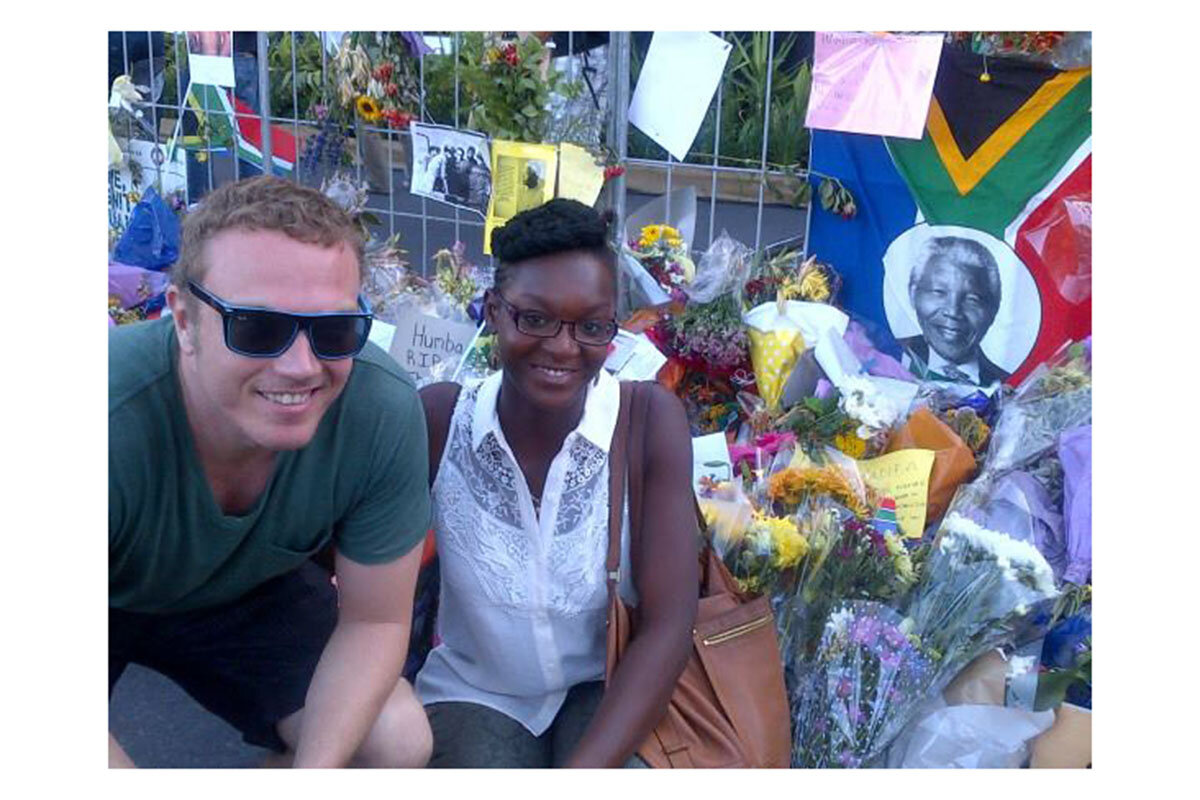

In a personal letter to her young children, the Monitor’s Johannesburg-based Africa Editor Monica Mark, who comes from Nigeria, explains what Mandela Day, celebrated this week, means to her and her white South African husband.

The annual commemoration of democratic South Africa’s first Black president’s legacy, marked by a call to charity, is sometimes hijacked by politicians seeking photo ops. And the country is very far from realizing the dream of a peaceful multiracial and just society that Mr. Mandela inspired.

She writes: “Mr. Mandela was neither the saint some people make him out to be, nor the sellout that others have painted him. He was simply a man who worked to be a vital part of a movement he realized was far bigger than he was. But he did not let bitterness destroy him, and if you draw anything from his story I hope it will be that it is possible to have so much grace for yourself that you have enough left over to extend even to those who grievously wrong you. ...

As you both grow older, mixed-race children of South African, British, and Nigerian heritage, I know you will start to understand the nuances of South Africa’s story, and of your own stories.

I hope we will have provided you with enough love, enough nurture, and enough wisdom that you will be able to go out into the world and live every day as Mandela Day.”

The meaning of Mandela, explained by a mother

Darling Daughter, dearest Son,

Earlier this week, I joined a group of moms in a preschool courtyard in our comfortable suburb of northern Johannesburg. We were there to help the 120-odd energetic, giggling kids scoop cups of lentils, rice, and soy mince into plastic bags that would then be handed out to families in need.

Across South Africa this week, thousands of schools, communities, businesses, and ordinary citizens carried out similar acts of charity in the name of Mandela Day, celebrating the legacy of democratic South Africa’s first Black president. Nelson Mandela saw his birthday as an opportunity for public service, hoping to inspire the next generation to take up the baton of social justice. “It’s in your hands now,” he famously said.

On television this week, we have seen South Africans of every age and race (and others – you know your mom is Nigerian and your dad is a white South African) carrying out these small acts of kindness that together are far bigger than the sum of their parts. We could almost believe that the whole nation had galvanized, even if just for one day, into living out the promise of its dream. We could almost forget the clouds of prejudice and hatred that are once again brewing over the land.

Yet it’s telling that ordinary people, not politicians, are behind this mass movement every year. And I hope you will be able to see through the folderol of politicians who use this day simply for photo opportunities.

The official Mandela Day website suggests, among other ideas, hosting a dinner where the meal budget is 5 rand ($0.3 cents) per person “as a way of identifying with the millions who live below the poverty line.” In South Africa, around 13 million people go to bed hungry every night.

Some people don’t have as much as we do, I explained to you, so we try to share with them. I told you this as we walked through a glitzy supermarket, pushing a laden trolley through gleaming rows. My explanation felt inadequate, and not just because you, my precocious girl, are only 3 years old. Afterward you were pensive, and I thought how upside down this world must seem through the eyes of an innately kind child.

Later, I bought a book for you, my easy-going son, for your first birthday. I flinched at the cost – 275 rand ($16) – but I bought it anyway because I wanted to treat you with a pop-up book you so love. That evening, I read about how a Mandela Day donation from a hydraulics firm enabled a rural school to open up its first-ever library. The school was in Marikana, where rich veins of platinum and diamonds thread the earth, but where the constitution’s promise of quality education for every child means little.

One day, your father and I will tell you as best as we can, the story of how things got this way in this country we have made our home.

But I would like to give you hope, too. The fire of freedom and justice still gleams through this broken world.

So I will also tell you about how, when Mr. Mandela died in December 2013, your father and I attended memorial services in Cape Town at which South Africans from every walk of life gathered to send Madiba to the ancestors. I wept as I listened to soaring songs of freedom.

In Grand Parade, the square where Mr. Mandela gave his first speech after 27 years of imprisonment, there unfurled a sea of tributes and flags.

We laid our own flowers. We took a photo of ourselves, smiling in the December sun and spirit of togetherness.

Sometime in the noise of that week, I went to visit a man called Ahmed Kathrada. Outside of South Africa, Mr. Kathrada isn’t as well known as Mr. Mandela, though we plan to make sure he is a household name as you grow up. Kathy, as he was known, was also a titan of the anti-apartheid movement who spent 26 years wrongly imprisoned. Yet he made time for me that December week.

He told me something that I’d like to pass on to you: “The ANC wasn’t only Nelson Mandela,” he said, of the African National Congress.

There was no rancor or judgment in his voice – days later he would struggle to compose himself as he spoke at the funeral of his former cell neighbor.

It was a passing comment but I think about it often.

Mr. Kathrada and Mr. Mandela understood that we are all part of a community and true progress comes from building a dream, a movement, or an ideal, brick by brick.

Mr. Mandela was neither the saint some people make him out to be, nor the sellout that others have painted him. He was simply a man who worked to be a vital part of a movement he realized was far bigger than he was. But he did not let bitterness destroy him, and if you draw anything from his story I hope it will be that it is possible to have so much grace for yourself that you have enough left over to extend even to those who grievously wrong you.

Mandela Day as a single day of the year or as a call to charity does not do justice to Mr. Mandela’s spirit. It is a value that must be lived as fully as possible each day. A vision that must be striven for until a wall is knocked down, an endangered being is safe, a promise is fulfilled.

As journalists, your father and I interview many people whose actions belie the grim headlines: the imam whose mosque gives out soup every day, not just on Mandela Day; the local electrician working in freezing conditions to get the lights back on; the woman who worked tirelessly to set up a world-class school in a township with no running water.

These unsung heroes provide true inspiration. There is much to be angry about, and I hope you will harness your anger so it propels you to change what you can.

As you both grow older, mixed-race children of South African, British, and Nigerian heritage, I know you will start to understand the nuances of South Africa’s story, and of your own stories.

I hope we will have provided you with enough love, enough nurture, and enough wisdom that you will be able to go out into the world and live every day as Mandela Day.

Listen

On a day of division, and beyond, a challenge to remain fair

Part of political division comes from ignoring others’ perspectives. What’s the answer? Serving facts without prejudice, and letting readers think for themselves. Here’s a conversation about our Jan. 6 coverage.

Nothing in recent history has underscored American divisiveness as emphatically as the events of Jan. 6, 2021.

The specific aims and motivations of those attending a protest-turned-riot at the U.S. Capitol surely varied. There were those who wandered the mall and marched to the Capitol, but didn’t go in. There were violent factions – those who sought to thwart a peaceful transition of power that they and a sitting president maintained had been wrongfully earned. That has brought calls for accountability. Hearings by a congressional committee have generated their own controversy.

Into all of that stepped a veteran Monitor reporter just a few days into her new assignment as congressional correspondent. Christa Case Bryant spoke to the Monitor’s Samantha Laine Perfas about the special challenge of the work, and about how the Monitor’s commitment to fairness in covering the news continues to guide her.

“The No. 1 thing you need to do if you want to be fair,” says Christa, “is constantly evaluating: Where are my blind spots? What am I missing? What perspectives am I not understanding or including?” Her sense of her contribution, and the Monitor’s: Work the space in the middle in a really thoughtful way.

“That brings out the best plausible arguments on either side of an issue and doesn’t prejudge what the reader should think about those,” says Christa, “but [instead] just pulls together the best thinking, the best, most relevant facts, and then [trusts] the reader to make an informed decision themselves about what they think about that. I think people are really yearning for that. And I think the Monitor is striving to do that.” – Samantha Laine Perfas, senior multimedia reporter

Note: This story is meant to be heard, but we appreciate that listening is not an option for everyone. You can find a full transcript here.

Monitor Backstory: Covering Jan. 6

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Post-pandemic workplaces that uplift

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

One visible measure of how the pandemic has changed society is in the places where people gather – or rather used to gather – to work together. The vacancy rate for office space hovers at near double the level of 2019, reflecting the enduring appeal of both remote and hybrid work. That is driving a focus on “repositioning” – or remodeling – buildings to make them a setting that workers enjoy.

Within offices, new designs underscore what business leaders see as a great shift: a redefining of work on the basis of spirituality. The rise of spirituality-driven organizations marks the beginning of an era “no longer defined by mechanization, isolation, competition, and self-interest, but by harmony, unity, spirituality, and shared destiny,” write Eden Yin, a business professor at the University of Cambridge, and Abeer Mahrous, a marketing professor at Cairo University.

After two years of working in isolation, many employees – particularly younger ones – are returning to work with a desire for connection and a renewed sense of higher purpose. And more businesses are trying to support the entire employee. If that offers a foretaste of a transformation across society, many trials of the pandemic will have led to an era of useful reflection on daily life.

Post-pandemic workplaces that uplift

One visible measure of how the pandemic has changed society is in the places where people gather – or rather used to gather – to work together. The vacancy rate for office space in the United States hovers at near double the level of 2019, reflecting the enduring appeal of both remote and hybrid work. That is driving a focus on “repositioning” – or remodeling – buildings to make them a setting that workers enjoy.

How old buildings are being made new reflects more than pandemic-related concerns, of course. Energy efficiency and other solutions for climate change come into play. Within offices, new designs underscore what business leaders see as a great shift: a redefining of work that tethers organizational strength to human wellbeing and worth.

The rise of spirituality-driven organizations marks the beginning of an era “no longer defined by mechanization, isolation, competition, and self-interest, but by harmony, unity, spirituality, and shared destiny,” write Eden Yin, a business professor at the University of Cambridge, and Abeer Mahrous, a marketing professor at Cairo University, in a paper published in the Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences.

After two years of working in isolation, many employees – particularly younger ones – are returning to work with a desire for connection and a renewed sense of higher purpose. That is resulting in office adaptations that improve mental well-being – design that creates more flow from inside to outside, color and lighting to lift moods, and shared work spaces to break down hierarchy and promote creativity and collaboration.

In Charlotte, North Carolina, the financial firm Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association has opened a new campus with walking trails, disc golf, and putting greens, according to Time magazine. “What really shifted with the pandemic was our focus on our outdoor spaces and amenities,” said Jennifer Cline, head of workplace strategy and execution.

Such elements, which can improve staff retention, point to a deeper shift that the pandemic has perhaps just accelerated. A growing number of studies are grappling with how to define spirituality in the workplace – not as a religious or denominational culture, but as a way of understanding how both commerce and humanity can move beyond the traditional yardsticks of data analytics and competitive market advantage.

“Spirituality is in fact an effective tool to make employees feel that they are an integral part of an organization,” notes a new study in the International Journal of Research and Development. “The unique characteristics that differentiate a spiritual organization from others are: strong sense of purpose, focus on individual development, trust and openness, employee empowerment and toleration of employee expression.”

In other words, more businesses are trying to support the entire employee. If that offers a foretaste of a transformation across society, many trials of the pandemic will have led to an era of useful reflection on daily life.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Just turn

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

As sunflowers naturally turn to the sun, so we can naturally soak in the healing, comforting light of God.

Just turn

My eyes take in the sunflowers,

emblazoned in jaunty rich gold. Angling

perfectly in one direction, turning

naturally, they reach for the sun

whose name they evoke.

Following the sun – no distraction

or deflection – they, strong and

stunning, soak in the light.

I think of how You, God – divine Soul,

the light of life – have created each

of us as Your serene child, spiritual,

unshadowed by fear, violence, destruction.

Turning to You like the sunflower

to the sun, we stretch toward the

shining truth of our spiritual nature.

Then we take hold of Your warm

outpouring of love that softens hearts,

heals, comforts, promises good.

Standing together, each of us drawn

irresistibly to the same spiritual light,

may we turn as one – emboldened – all

drinking in equally Your big blessedness.

A message of love

A steeplechase record

A look ahead

Thanks for ending the week with us. Come back Monday, when we’ll have a story examining the need for leadership in a chain of command as seen through the lens of the Uvalde tragedy.