As the national capital, Washington is the place aspiring and veteran navel-gazers converge, endlessly analyzing wrinkles in American politics that average Americans don’t even see.

It’s an art and an industry. Ideally, they would value the perspectives of farmers and firefighters, teachers and truck drivers – welcoming their ideas and refining them through all this thinking and talking.

But sometimes those ideas instead get mired in bureaucracy, hierarchy, or party politics. And now, amid deepening partisanship, many feel the wheels of Congress have largely ground to a halt. That has led to a crisis of public confidence in the institution. Only 2% of Americans today have a “great deal” of trust in Congress, the lowest figure in 50 years of Gallup polling.

Civilians don’t have the luxury of letting things grind to a halt in their trades, businesses, or local PTAs. They have to keep solving problems, or face the consequences. So as the new Congress begins today, we offer the perspectives of three individuals who have navigated crises in which stalemate or failure was not an option.

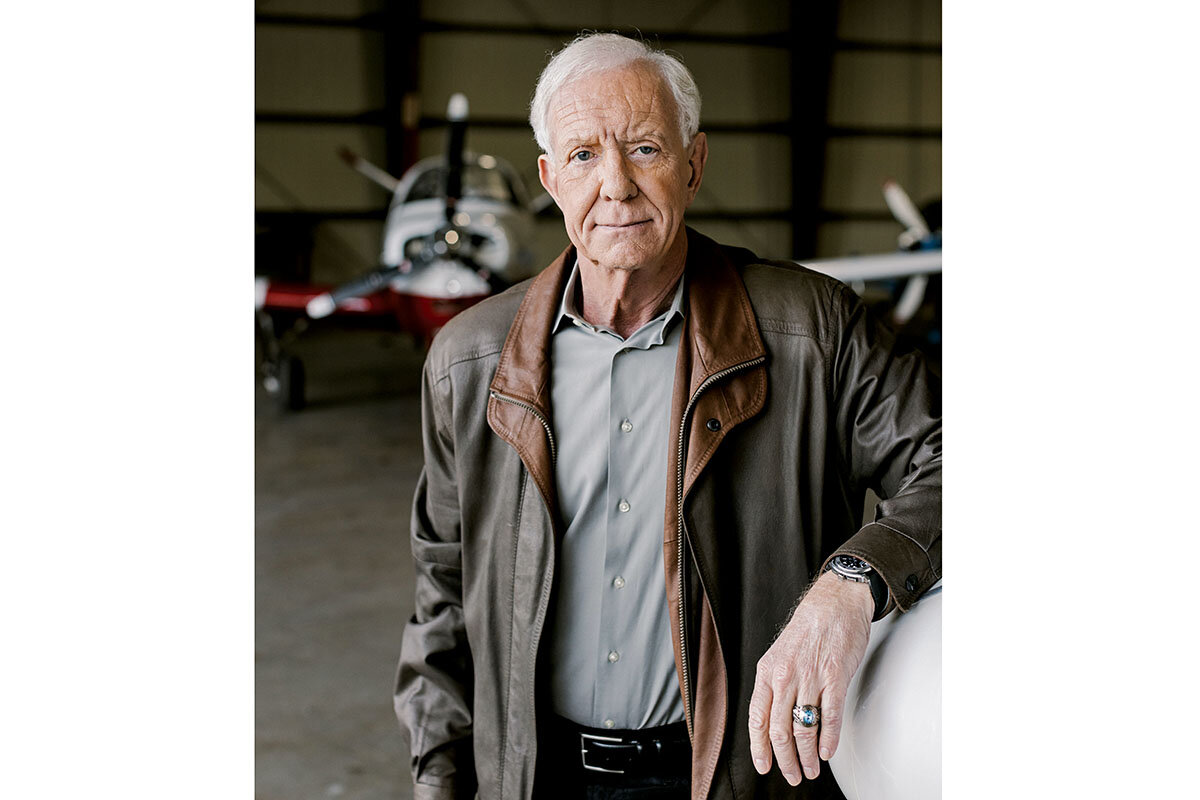

Capt. C.B. “Sully” Sullenberger, the US Airways pilot who made a forced landing on the Hudson River in January 2009, addresses the importance of continuing to take decisive action even when you don’t have good options.

Antoinette Tuff, a bookkeeper in 2013 at a Georgia elementary school who single-handedly thwarted a school shooting, points out that it’s not only Congress that sets the tone for the country. It starts with each one of us, at home, says Ms. Tuff, now working as a leadership coach.

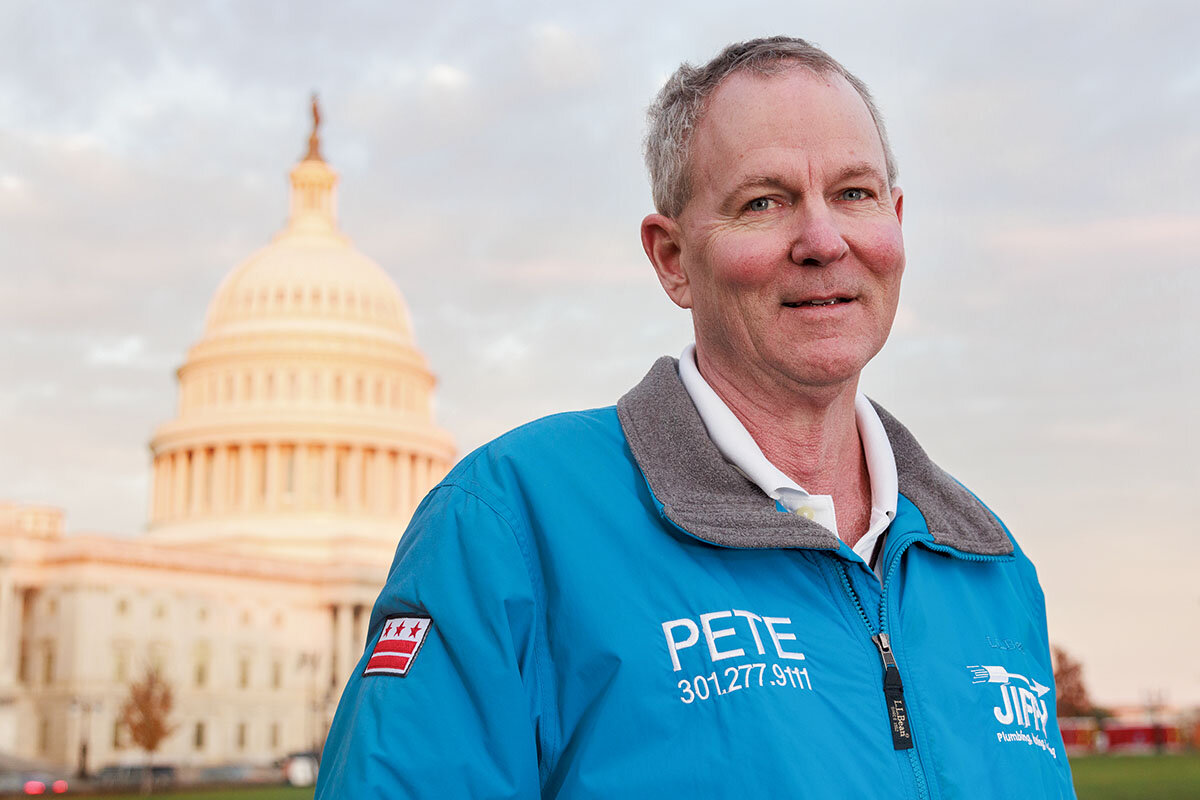

And Pete Kristiansen, a veteran plumber in Washington who has worked for famous writers, CEOs, and nearly every foreign embassy in the nation’s capital, shares how more urgency and pragmatism could get Congress’ plumbing working again.

These individuals have faced crisis head-on, and demonstrated the responsibility, integrity, and compassion needed to lead in the moment. Many consider them heroes, but we did not choose them for their titles, nor for their political affiliation or perspective, but rather for their ability to remain poised in high-pressure situations and keep the trust of the people they were hired to serve. Here, they distill the lessons they have learned and apply them to an increasingly polarized Congress. They make the case to top lawmakers about why this type of leadership is needed today, based on their diverse viewpoints in society

“Sully”: In togetherness, there is responsibility

Just after takeoff, the geese hit. The plane shuddered. Flames burst out of the engines. The pilot, quickly losing altitude, turned down the Hudson River. Then he addressed the passengers.

“This is the captain,” he said. “Brace for impact.”

Capt. C.B. “Sully” Sullenberger’s calm, authoritative decision-making during the 208 seconds between the bird strike and landing in the Hudson that day in January 2009 instantly made him a global hero.

While flying a jet is admittedly different from shepherding America’s 535 elected representatives, members of a gridlocked Congress may draw lessons from his decisive leadership.

An ex-fighter pilot with decades of experience, Captain Sullenberger knew that the sudden loss of engine thrust required him to prioritize the most important problems and ignore everything else. Even as the plane’s warning systems were blaring, “Terrain, terrain, pull up!” he was judging the optimal angle and timing for touchdown. He took an “extravagant” three or four seconds to choose his few words to prepare the crew and project courage to the passengers who were about to land in a river on a frigid January day.

“You keep on solving problems as long as you can, with as much altitude or airspeed as you have,” says Captain Sullenberger, who together with co-pilot Jeff Skiles and their crew saved all 155 people on board.

As the new Congress begins in January, leaders take their seats in America’s cockpit at a time when many see flashing red lights across the dashboard. Constituents want a course correction. And he has a few ideas about how to prioritize the challenges at hand, address them with persistence and discipline, and maintain courage and confidence even as the warning systems sound.

That requires a leadership that serves a cause greater than oneself, and to remember – like that planeload of people he piloted to safety – we’re all in this together. “When we share common values, and common humanity, there’s little we cannot accomplish,” he says.

A long-term optimist but short-term realist, Captain Sullenberger sees grave threats to American democracy, including politicians questioning the outcomes of elections for their own gain.

“We’ve all gotten a real wake-up call,” he says. “We’ve had the biggest civics lesson of our lives.”

That requires Democrats and Republicans to put aside policy differences and save our democracy, says the pilot, who after years as a registered Republican left the party and came out strongly against the GOP and the president during the Trump administration. He is now a Democrat.

Actively defending American democracy isn’t a partisan issue, but a moral one, he says. “It is a black-and-white question of right and wrong, and a question on which no one can be neutral without being morally bankrupt or cowardly,” says Captain Sullenberger, who would like to see Congress formalize long-standing norms that have been disregarded of late. One example he’s personally familiar with is the Senate holding up confirmation of dozens of presidential nominees, including his own June 2021 nomination and December 2021 confirmation as ambassador to the Council of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO).

So how do you build a bipartisan coalition to save democracy in such divided, hyperpartisan times?

Personal diplomacy. Taking the time to get to know someone and building trust. When you find ways to work together on projects with a specific purpose, and succeed, he says, that opens the way for more collaboration. For example, as the U.S. ambassador to ICAO, he helped to build consensus among a number of nations to resolve an airspace boundary issue in the Middle East.

In addition to trust, other key components he cites are agreeing on facts and making evidence-based decisions. In the ICAO discussions over the airspace boundary issue, for example, providing a detailed description of the operation of air traffic control helped bring others on board. The council was also able to build consensus on the threat of climate change through scientific data and understanding, he adds.

Sometimes horse-trading is necessary, he admits. It may not be perfect, but you can build on it later. On that clear January day when he had three minutes to save a plane full of people, none of his options were good. “I chose the least bad option,” he says. “And I was glad to have it.”

What helps in politics, he adds, is identifying shared values, finding the lowest common denominator to build on, and avoiding tribalism.

Among the core values he sees as important are saving the climate, striving for justice, and providing education. He doesn’t plan to run for office himself, but he’d like to see good candidates who can articulate the importance of these values in concrete, specific terms. Take climate change, which he describes as a “literally existential crisis” that threatens the future of the human species. Though the parties differ on their approach to climate issues, he sees the scales tipping toward “acknowledging reality,” in part because the changing climate is something people can see personally, nationally, and globally.

Citizens and voters need to be informed and engaged, too, he adds. It’s not a time for “sleepwalking” through one’s civic duties.

“We have to tell people what the stakes are, and why it matters, and how life will be better if we do these things together,” he says. “And there’s really no alternative to it. Everything else is failure.”

A plumber’s integrity: Urgency and pragmatism

Decades of work in the shadow of the U.S. Capitol give “Pete the Plumber” – Pete Kristiansen – a strong perspective on how Congress might be more effective.

If Pete Kristiansen weren’t colorblind, he might be flying 30,000 feet above American politics, fulfilling his youthful dream of becoming a pilot. Instead, he’s on his hands and knees in the nation’s capital, sniffing drains and solving the plumbing woes of important people – from foreign diplomats and congressional staffers to famous authors and CEOs. He also sees a side of America many elites don’t, walking into the living rooms and bathrooms of people living in humble circumstances, sometimes too poor to pay their heating bills.

Mr. Kristiansen thinks people like him could bring some wisdom to the gilded halls of the U.S. Capitol, where a little blue-collar street sense could go a long way. Moreover, after decades of responding daily to emergencies, he says plumbers possess a sense of urgency and pragmatism often lacking in Congress.

“We’re different; we have to get things done,” he says in his office, where he starts at 5 a.m. six days a week. “We’re there to solve a problem.”

On a recent morning, he pulls out of the office parking lot at 5:48, equipped with tools, S. Pellegrino, and a can of Pringles.

Ten minutes later, he swings his lanky legs out of his truck and steps into the moist soil of a partially excavated driveway. Shining a flashlight around, he sees the drainage isn’t working right and the sewer pipe is corroded. He advises the bleary-eyed owner pacing in front of a parked Bobcat that she needs a new trench drain – and may need to dig up everything and replace the pipe, too.

“Unfortunately, this can be expensive,” Mr. Kristiansen warns her.

The tradesman now called “Pete the Plumber” by homeowners across the Washington area, got his start as a University of Maryland student looking to earn pocket money. Construction was a good way to do it, at least for a tough kid who spent winters repairing fences on his parents’ Thoroughbred farm in Maryland. The day Ronald Reagan’s inauguration was moved inside the Capitol rotunda because of subzero wind chills, Mr. Kristiansen was earning $11 an hour on an outdoor job. He’d been in that rotunda once, as an elementary school student. “A big round room,” he recalls.

He worked hard in school and got B’s and C’s. But he’s mastered the plumbing, gas fitting, and HVAC codes – a stack of reading thicker than most congressional bills. And he’s the guy at a party who finds a corner to read the almanac. Ask him the capital of Madagascar, and he not only immediately responds – correctly – Antananarivo, but also holds forth on the country’s woes with deforestation and gemstone mining.

And he’s worked in nearly every embassy in Washington – seen the inner sanctums, the fancy dinners, even a sitar concert. It’s like traveling the world, without boarding a plane.

He was one of the first people to enter the long-abandoned Lithuanian Embassy after the country won its independence from Moscow. When the Lithuanians had his company throw a bathtub out of an upper-floor window, the Cubans next door thought a bomb had gone off. But he’s friendly with the Cubans, too; they always send him a Christmas card.

When the United States withdrew from Afghanistan in 2021, he called up an Afghan contact to check in; two days later, they were sitting on cushions in the embassy together, eating a traditional meal as the government fell to the Taliban.

And yet, he thinks it’s a mistake for the U.S. to get so involved abroad. “I don’t think there’s anything wrong with Congress other than we’re spending a lot more on other countries than on us,” says Mr. Kristiansen, who fundamentally supports government and always tells his accountant to give Uncle Sam all the taxes he needs. “Money could certainly be better spent – not building a school on the side of a mountain in a war-torn country that no one’s going to use,” he says, referring to Afghanistan, where the Taliban has since banned girls from attending high school and university.

Take people who got hooked on opioids. “We lost a generation in West Virginia,” he says. “Everyone seems to think, ‘Oh, that’s OK, it’s West Virginia.’”

Or take the people who lost their jobs during the pandemic, he says. Why was Congress sending stimulus checks to people making $120,000 a year when others lost their homes because they couldn’t afford rent?

“I’m a firm believer in exceptions to help people,” says Mr. Kristiansen.

As he returns to his office, a man on a bike comes whizzing past. Mr. Kristiansen yells, “Hey, hey, hey!” The man, who lives under a nearby bridge, circles back to chat. As they catch up, Mr. Kristiansen grabs a Clif Bar from the box in his back seat and hands it out the window.

“Aw, thanks,” the guy says.

“There’s a guy who lives under a bridge,” muses Mr. Kristiansen after they part. That’s not one of the problems he can solve today. And he knows it could take Congress more than a day, too. But he’d like to see lawmakers step it up.

“I understand laws enacted by Congress are big, important things. But we do big, important things, too, with gas and sewers,” says Mr. Kristiansen, who earlier in the day pointed out a six-figure job his company had done recently. “So if we can get things done, they should, too.”

The compassion in seeing everyone in a new light

Thanks to Antoinette Tuff, Decatur, Georgia is not a name forever joined with Uvalde, Parkland, and Newtown. With her coaxing, a would-be school shooter put down his weapon, and all 800-plus students were saved. So while gun safety is the No. 1 issue she’d like to see the new Congress take up, she also sees a role for everyday citizens in establishing a better tone in the country.

“I think it starts at home,” says Ms. Tuff. For her, that means starting her day with God, and following the example Jesus set when he quieted a storm with “Peace, be still.” “Then,” she says, “you can leave your home in a peace when the wind is raging.”

On Aug. 20, 2013, she woke up at 4 a.m. As usual, she read the 23rd Psalm: “The Lord is my shepherd. ... Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil.”

Ms. Tuff, distraught after her husband of 33 years had left her for another woman, had repeatedly tried to take her own life. She was working three jobs, yet just had to borrow money to get her car out of the shop. She didn’t know yet that later that day, the phone would ring with more bad news. It was the bank: Unless she could come up with $14,000, it would repossess her house, her car, and her furniture.

“I’m just sitting there like, ‘OK, God, what do I do now?’” recalls Ms. Tuff, who at the time was a bookkeeper at the Ronald E. McNair Discovery Learning Academy in this Atlanta suburb.

Then the school secretary called. Ms. Tuff was needed to fill in. She dried her tears and went to the front office.

A few minutes later, Michael Hill walked in with an AK-47 and a backpack full of ammunition rounds. “We’re all going to die today,” he announced.

She was terrified, but her motherly instinct kicked in – not just for the students, but for the 20-year-old gunman. “At the end of the day ... he’s somebody’s child,” she says.

As he approached the door to the adjacent teachers’ lounge and was about to start shooting, she recalls telling him, “Mmm-mm, we’re not doing that today.”

And thus began an extraordinary encounter between a Black woman who had hit rock bottom and a young white man struggling with mental illness, an encounter that ended with him surrendering to police.

“We’re not going to hate you, baby,” she said nine minutes into her 911 call, as the young man indicated he was willing to stand down. “It’s going to be all right, sweetie – I just want you to know that I love you though, OK?

“And I’m proud of you – that’s a good thing that you just givin’ up. And don’t worry about it – we all go through something in life,” she added.

Now, nearly a decade later working as a leadership coach, she describes a country in turmoil, with disgruntled employees, irate customers, road rage, and active shooters on the rise. It’s not just schools, either; she points to the recent Walmart shooting in Virginia in which an employee killed six others and then himself. She sees a nation focused on self, which has lost the compassion it once had.

And that turmoil, focus on self, and lack of compassion are reflected in Congress, too: “I think we just forgot that we was the United States of America,” she says.

Ms. Tuff calls in every day at 5 a.m. to a prayer line on which she joins with others to pray for, among other things, the individuals in Congress, the protection of them and their families, and guidance in their work. It shouldn’t be about self, or political party, she says. “I think we need to say, ‘What’s going to be the best for the people?’”

And a key way she’d like to see them do that is by asking, “Who is this bill going to affect?” and then bringing those people to the table and giving them a voice. For example, she says, school meetings tend to feature upper management – the superintendent, the board of education. But they don’t typically involve the teachers or secretaries, cafeteria staff or custodians. That more inclusive approach requires compassion and a confidence that welcomes others’ ideas, rather than feeling threatened by them.

Sometimes people don’t see their own – or others’ – value until they’re tested, adds the woman who went from being a struggling bookkeeper to being a guest of Michelle Obama at the State of the Union address.“You’re going to see yourself in a whole new light,” says Ms. Tuff.

So maybe it’s not such a bad thing that the United States of America is being tested. Maybe Congress and the citizens it serves will come to see themselves in a new light, too.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to clarify Capt. Sullenberger's current political affiliation.