- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Finding the courage to share a difficult story

My story in today’s Daily is the hardest I’ve ever written.

To report it, I needed to talk to people who lost family in a tragic bus crash in Canada that killed 16 members of the Humboldt Broncos hockey team in 2018. And I needed to ask them how they felt about the possibility of forgiveness for the driver who was responsible.

As a reporter for The Christian Science Monitor, where one of our driving missions is to shine light, I’m used to finding sources who are eager to tell me their stories. But this one raised particularly difficult questions. I got far more rejections than invitations to talk. Some of the responses were full of anger – directed squarely at me and this newspaper.

At times I was deeply hesitant to continue. Were we, a newspaper founded on the promise to “injure no man,” in fact doing just that?

Many consider “the media” to be arrogant and self-serving. But most of the journalists I know are full of self-doubt. We feel a deep responsibility when writing about someone’s life, and it’s a terrible feeling to get it wrong. In my early career, as a foreign correspondent in Mexico in a job I loved, that burden felt so heavy at times that I considered leaving.

Years later, this story had me once again questioning everything I was doing. I sat for days trying, and failing, to write the first sentence.

And then the words of Christina Haugan came to mind.

Her husband, the team’s widely adored head coach, had been killed in the crash. We had spoken about whether it was hard for her to talk about her journey of forgiveness, knowing it hurts other families who don’t feel the same way. She, like every person in this piece, was adamant that her journey is not the only one – or that she is somehow better because she has forgiven.

But, she said, if she can help just one person – anyone, anywhere in the world, who is grappling with unthinkable grief – it’s worth it to speak out. And it was with those words that I found the courage to share her story.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Can Joe Biden win back Americans’ confidence?

As the president gears up for an expected reelection bid, he can tout accomplishments from low unemployment to new infrastructure projects. But 4 in 10 Americans say they’re worse off than two years ago.

President Joe Biden’s first two years in office have been a study in contrasts.

The nation has avoided a recession, and unemployment is at historic lows. But inflation, while declining, remains high – and a stunning 41% of Americans say they’re worse off today than they were two years ago.

President Biden restored the United States’ image as a strong global leader in supporting Ukraine against Russia, following a disastrous pullout from Afghanistan. And the Democrats bucked history in November’s elections, adding to their Senate majority and only barely losing control of the House. While divided government foretells gridlock and a slew of investigations, the Republican-held House also provides Mr. Biden with a foil. There’s a reason first-term presidents of both parties have often won reelection after losing ground in the midterms.

Still, Mr. Biden faces a difficult political road ahead. Arguably, his biggest political vulnerability centers on a factor over which he has no control: his age. When the nation’s first octogenarian president delivers his State of the Union address Tuesday night, attention will be trained as much on his demeanor as on his words.

“The big question that looms large over this moment is, is he up to the task of running again?” says David Barker, a professor of government at American University.

Can Joe Biden win back Americans’ confidence?

President Joe Biden’s first two years in office have been a study in contrasts: of highs and lows, triumphs and tragedies, stability and chaos.

The nation has so far avoided a recession, and economic forecasts are looking rosier, with unemployment at historic lows. But inflation, while declining, remains high – and many Americans are still hurting. A stunning 41% say they’re worse off today than they were two years ago.

President Biden restored the United States’ image as a strong global leader in supporting Ukraine against Russia, following a disastrous pullout from Afghanistan in 2021. But the latest clash of superpowers – in which a suspected Chinese spy balloon traversed the entire U.S. before being shot down – underscores an increasingly adversarial relationship with China that could deteriorate quickly.

In contrast with the tumultuous White House of former President Donald Trump – already an announced candidate for 2024 – Mr. Biden has surrounded himself with loyal advisers who rarely leak to the press, creating a sense of stability in uncertain times.

And in perhaps his biggest political triumph, beyond beating Mr. Trump in 2020, Mr. Biden’s Democrats bucked history in November’s midterm elections, adding to their Senate majority and only barely losing control of the House. While the return of divided government foretells legislative gridlock and a slew of investigations, including into Mr. Biden’s son Hunter, the Republican-held House also provides Mr. Biden with a foil. There’s a reason past first-term presidents of both parties have gone on to win reelection after losing ground in the midterms.

Still, Mr. Biden – by all indications planning to run for reelection – faces a difficult political road ahead. Arguably, his biggest political vulnerability centers on a factor over which he has no control: his age. When the nation’s first octogenarian president delivers his State of the Union address Tuesday night, attention will be trained as much on his demeanor, clarity, and energy as on his words.

“The big question that looms large over this moment is, is he up to the task of running again?” says David Barker, a professor of government at American University. “He has to continue to project as much vigor and strength and vibrancy as he can, and hopefully not stutter, hopefully not stumble over his words or look in any way inarticulate.”

Biden defenders note that he’s always been gaffe-prone, and has dealt with a stutter since childhood. What’s more, aging is highly individual; plenty of Americans work into their 80s. But running for president – and being president – is another matter, especially with the return of in-person events and constant travel. Even for younger candidates, the pace can be grueling. Presidents running for a second term can campaign by governing, but just being president visibly ages the best of them.

At last week’s gathering in Philadelphia of the Democratic National Committee, Mr. Biden’s age was a topic of conversation. Even some of these loyal party members expressed concerns, but on balance most came down on the side of favoring a reelection bid. Chants of “four more years” rang out.

The Democratic electorate seems much more skeptical. Only 37% of the party’s voters currently want Mr. Biden to run again, down from 52% right before the midterms, according to a new Associated Press-NORC poll.

When confronted with concerns about his age, Mr. Biden typically offers a defiant comeback: “Watch me.” But on Tuesday night, speaking during prime time before a joint session of Congress in what’s widely seen as a soft launch of his 2024 campaign, the president also wants Americans to listen.

Touting his accomplishments

Mr. Biden will have plenty to tout from the past year, beyond a strong labor market: progress in combating COVID-19; infrastructure projects around the country funded by the bipartisan, $1.2 trillion bill that passed in 2021; and the Inflation Reduction Act, which addresses climate change and prescription drug costs, among other provisions.

The president is also sure to celebrate bipartisan passage of measures on marriage rights for LGBTQ and interracial couples; gun safety; semiconductor manufacturing; and benefits for veterans exposed to burn pits. And he will decry the overturning of Roe v. Wade last June, which had enshrined a nationwide right to abortion for nearly 50 years. Divided government makes federal legislation impossible; action on reproductive rights is now firmly state by state.

U.S. support for Ukraine will feature prominently, as it did in Mr. Biden’s first State of the Union speech last March, days after the Russian invasion. U.S. funding has passed with bipartisan support, but as the war drags on with no end in sight, the president may find it a heavier lift to keep the funds and weapons flowing. Numerous polls show declining public support for aid to Ukraine, especially among Republicans.

One issue Mr. Biden is almost sure to avoid Tuesday night is the classified documents found in his home in Wilmington, Delaware, and his former office in Washington, spurring the appointment of a special counsel. The discovery has effectively deprived Mr. Biden of a talking point against Mr. Trump – also found to have classified documents in his home and also under investigation by a special counsel – should they face each other in 2024.

Far more politically consequential are the issues that affect daily life. And strengthening the economy is by far Americans’ No. 1 policy priority, as seen in the latest Pew poll, with 75% of Americans citing it. Three years since the start of the pandemic, COVID-19 is now a priority for only 26%.

Still, Mr. Biden will have to walk a fine line between crowing about successes and being mindful of those who are struggling, be it people who have to work three jobs to make ends meet or those who have lost family to COVID-19. That’s where the president’s skill at showing empathy will surely come in.

Mr. Biden’s public approval ratings have been well below 50% since the summer of 2021, a source of frustration for the president’s allies.

“He’s still so underestimated in terms of what he’s gotten accomplished,” says Celinda Lake, a Democratic pollster on Mr. Biden’s 2020 campaign.

Ms. Lake cites infrastructure investments as popular with voters and applauds the president’s recent trips around the country highlighting bridges, tunnels, and other projects.

“Democrats give him credit, but swing voters are still not paying that much attention to what he’s gotten done,” Ms. Lake says. “They’re very focused on, ‘What are you doing for me next?’ They’re very unhappy with things, and so therefore don’t tend to process the accomplishments much.”

Confrontation vs. conciliation

The optics of this year’s State of the Union will be different in a key way: Sitting behind the president will be the new Republican speaker of the House, Rep. Kevin McCarthy of California. The two met last week, the start of a monthslong debate over Congress’ need to raise the government borrowing limit – the debt ceiling – to avoid a catastrophic default. Republicans are demanding spending cuts in return.

The debt ceiling negotiations are one of many areas where Americans say they want the two parties to work together for the common good. Ditto with the porous southern U.S. border. But it’s not so simple. Voters also want their leaders to be “fighters” – to stand up for their beliefs.

Henry Olsen, a senior fellow at the conservative Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, says he’ll be watching Tuesday to see how the president strikes a balance between confrontation and conciliation.

“Biden, I think, needs to show both,” Mr. Olsen says. “He needs to show confrontation to draw the general-election contrast and to make the progressive left satisfied with him. He needs to show conciliation for the general election as well.”

The only question, he adds, is “What’s the balance?” If it’s 80% confrontation and 20% conciliation, that lowers the chance of getting things done. “If it’s 60-40 in favor of conciliation, that raises the discord on the left.”

Mr. Biden will rely on his decades of Washington experience as he tries to thread that needle. He’ll also rely on his inner circle of longtime advisers – now minus his longtime chief of staff, Ron Klain, who stepped down last week in a tearful goodbye ceremony. The president’s new chief of staff, Jeff Zients, is hailed for his executive ability – most recently, as COVID-19 response coordinator – but isn’t seen as having the political savvy of Mr. Klain.

The chief of staff transition might seem like so much “inside the Beltway” minutiae, but it matters, says Chris Whipple, who interviewed many key players, including the president himself, for his new book, “The Fight of His Life: Inside Joe Biden’s White House.”

“This is a really battened down, disciplined, leakproof, on-script White House most of the time,” he says, and as Team Biden gears up for the reelection campaign, having an effective chief of staff “makes all the difference.”

Even after “all the stuff they’ve dealt with,” Mr. Whipple says, “now comes the hard part.”

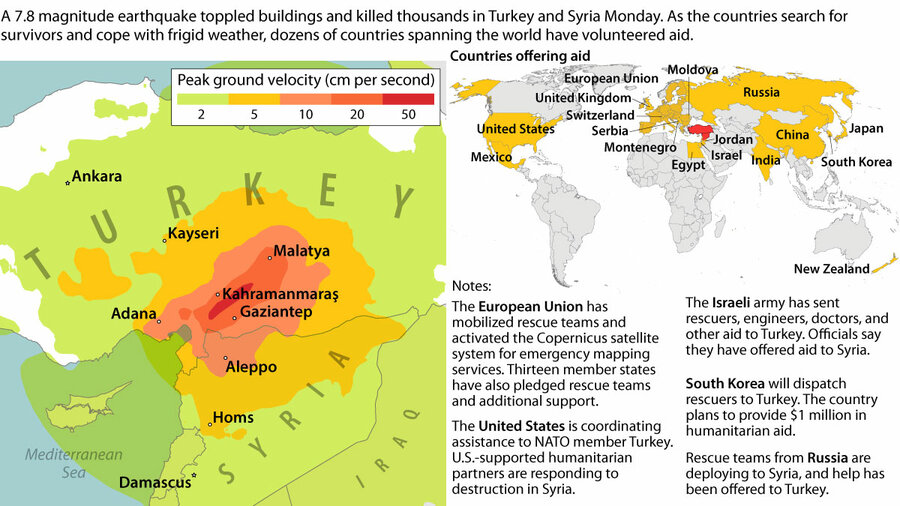

Turkey and Syria’s earthquake triggers a global outpouring

In a time of great need, even countries that have chilly relationships with Turkey and Syria have stepped up to help. Here’s a snapshot of how the world has responded.

United States Geological Survey, Associated Press

Why is democratic India helping Russia avoid Western sanctions?

Russia’s ability to endure sanctions relies on the reluctance of countries like India to join the West’s economic embargo. The trade channels being formed could have lasting geopolitical effects.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Much of the Global South – including key countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America – has declined to join the anti-Moscow sanctions regime, and has instead chosen to maintain active political and commercial relations with Russia.

India, a fast-growing, secular, English-speaking Asian democracy with an increasingly Westward-leaning popular culture, serves as a prime example as to why the West is not getting buy-in for sanctions.

Early in the war, U.S. diplomats made strenuous efforts to convince Delhi to condemn Russian actions in Ukraine, or at least limit its long-standing political and trading relationship with Russia. Indian leaders refused to vote against Moscow in the United Nations or to join in any level of the sanctions campaign. Instead it accepted Russian offers of price discounts, which led to a vast increase in India’s imports of Russian oil.

“Basically, India is protecting its national interests,” says Nandan Unnikrishna, an expert with the independent, Delhi-based Observer Research Foundation. “It’s known that we have conveyed our private displeasure to the Russians, but we’re not joining any unilateral sanctions. It seems to me that the U.S. has accepted this and the kind of pressure they were putting on India last March hasn’t figured in recent contacts.”

Why is democratic India helping Russia avoid Western sanctions?

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine a year ago, the West has tried to curtail Moscow’s ability to finance the war by restricting its lucrative energy exports.

Over that same time, Asia’s biggest democracy, India, has ramped up its imports of Russian oil by a whopping 33 times.

The future world order may turn on realignments like this.

Much of the Global South – including key countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America – has declined to join the anti-Moscow sanctions regime, and has instead chosen to maintain active political and commercial relations with Russia. This is part of the reason the Russian economy has so far avoided the intended body blows, but it is also reshaping global trading patterns in ways that might outlast the conflict.

In particular, Russian efforts to evade the restrictions that come with using the U.S. dollar in international transactions may be accelerating the process of dethroning the dollar as the world’s established reserve currency, with vast implications for U.S. financial and political leadership down the road.

India, a fast-growing, secular, English-speaking Asian democracy with an increasingly Westward-leaning popular culture, serves as a prime example as to why the West is not getting buy-in for sanctions – and how the world may realign.

“India is not happy with what Russia did,” says Nandan Unnikrishnan, an expert with the independent, Delhi-based Observer Research Foundation. “But in the longstanding relationship we have with Russia, they have repeatedly proven to be good partners for India. India does not want to lose a friend. As for the moral argument the Americans often cite, well, we don’t accept that. It hardly bears mentioning that we can think of zillions of examples of Western hypocrisy.”

Protecting national interests

Early in the war, U.S. diplomats made strenuous efforts to convince Delhi to condemn Russian actions in Ukraine, or at least limit its long-standing political and trading relationship with Russia. While privately making clear its disagreement with Russia’s war – a view shared by much of India’s elite – Indian leaders refused to vote against Moscow in the United Nations or to join in any level of the sanctions campaign. Instead it accepted Russian offers of price discounts, which led to a vast increase in India’s imports of Russian oil.

“Basically, India is protecting its national interests,” says Mr. Unnikrishnan. “It’s known that we have conveyed our private displeasure to the Russians, but we’re not joining any unilateral sanctions. It seems to me that the U.S. has accepted this and the kind of pressure they were putting on India last March hasn’t figured in recent contacts.”

But the structure of Russia-India trade, which has languished since the collapse of the USSR, may be set to change due to Russia’s refusal to use the dollar in its transactions with India.

Moscow favors a “ruble-rupee” trade mechanism, which may be more complicated and costly than doing business in dollars, but it evades the U.S. financial controls that go with dollar transactions, and strengthens the bilateral relationship with India. With the huge increase in Russian oil imports to India, Moscow is building up a massive surplus of rupees that Delhi hopes it will invest in India or use to buy more Indian products.

“The immense increase in Russian energy exports to India looks like a lasting phenomenon. India needs it,” says Nivedita Kapoor, an Indian expert currently with the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. “If the ruble-rupee mechanism is fully worked out, it should lead to a big increase in Indian products being exported to the Russian market.”

Though India does not produce some of the items Russia desperately needs due to Western sanctions, such as microchips, it does make plenty of others.

“Right now the focus is on pharmaceuticals, electronics, machinery, chemical products, medical instruments, and agricultural products,” says Dr. Kapoor. “We have already been exporting these goods to Russia, and there is potential for major increases. ... It may be harder to expand the list due to the threat of secondary sanctions. In this environment, the Indian private sector looks at Russia as a risky market. But the immediate potential is very big.”

Mr. Unnikrishnan says that one way to avoid the long arm of U.S. sanctions – which would hit any attempt to export items with U.S. parts or technology to Russia – is to set up distinct businesses that deal only with the Russian market, as is reportedly already being done in China.

“Some Indian businesses are exploring ways to set up separate production facilities, only for export to Russia. The Indian government is already in the process of certifying Indian generic pharmaceuticals for export to the Russian market,” he says. “There are a lot of ways that joint India-Russia collaboration and trade can be expanded.”

“A costly and inefficient economic strategy”

Current Russian policy is to push for abandoning dollar trade in every area, and there has been a lot of talk about creating an alternative currency, perhaps for use among the BRICS trading bloc.

It’s all easier said than done, says Konstantin Sonin, a Russian expatriate professor at the University of Chicago.

“De-dollarization would be very costly to implement,” he says. “People use the U.S. dollar because it’s a more stable, reliable, and liquid currency than any other. There is a premium to be paid for using riskier assets. Nothing Russia can do is likely to dislodge the U.S. dollar from this role. The main threats to the dollar are potential internal instability in the U.S., which might undermine the dollar’s value, or the possibility that some other big country, like China, might develop a viable alternative.”

He says that countries like India are taking advantage of Russia’s current weakness to drive hard bargains, for cheap energy and increased exports to Russia, that benefit their own economies. Russia accepts this because its options have been limited by the global sanctions regime imposed by Western powers.

“This makes sense for Russia only as part of a war-fighting strategy in isolation from the West,” says Dr. Sonin. “Otherwise it’s a costly and inefficient economic strategy for Russia to pursue in the long term.”

Dr. Kapoor argues that there is only one way that the benefits of increased Indo-Russian trade can be permanently locked in.

“The best solution would be for Russia to make an early end to this war,” she says. “We can envisage a situation where Western companies have already exited the Russian market, and burned their bridges, while the Indian private sector no longer regards business with Russia as a risky proposition, carrying the threat of secondary sanctions. All that would go away for us, but we need to see an end to this war.”

A deeper look

What does forgiveness mean? A Canadian bus crash, five years later.

Where does punishment end and healing begin? In the wake of a tragic bus crash, Canada grapples with accountability, justice, and mercy for a remorseful driver.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 16 Min. )

Because of Jaskirat Singh Sidhu, Christina Haugan’s husband is dead.

Five years ago, the inexperienced semi driver barreled across the Canadian prairie through a blinking rural crossroad stop sign, colliding with the bus of the beloved Humboldt Broncos junior hockey team that her husband coached. Sixteen people died.

But last year, Ms. Haugan’s thoughts kept returning to Mr. Sidhu, who was sentenced to eight years in prison and is now facing deportation to his native India.

“As much as my life changed that day, so did his,” Ms. Haugan says. Mr. Sidhu and his wife will “never be the same either.”

Some of survivors and victims’ families view the possible deportation of Mr. Sidhu as a cruel form of double punishment, forged in an out-of-touch, “tough-on-crime” era. Yet the idea of forgiving Mr. Sidhu, or stopping his deportation, remains divisive. Exalted for its healing potential, forgiveness can also amplify grief and blame. The focus trying to heal from the tragedy, Humboldt’s mayor says, has meant that even broaching the subject of forgiveness, or the merits of Mr. Sidhu’s deportation, has been largely sidelined from public conversation in the small Saskatchewan town.

“It’s easy to say that you forgive him. But it’s maybe a little bit harder to actually, genuinely want good for him ... and to be able to live that out,” says Ms. Haugan.

What does forgiveness mean? A Canadian bus crash, five years later.

Because of Jaskirat Singh Sidhu, Christina Haugan’s husband is dead.

But every April 6, she feels tugged toward the inexperienced semi driver who, on that day in 2018, barreled across the Canadian prairie through a blinking rural crossroad stop sign, and collided with the bus of the beloved Humboldt Broncos junior hockey team that her husband coached.

Mr. Sidhu’s moment of dangerous inattention killed 16 people. From the start, the tragedy was experienced as Canada’s – as if it happened to everyone who heads onto the ice, everyone who sends their kids on a bus, anyone who knows what it means to feel Canadian.

Every year on that anniversary, Ms. Haugan feels enveloped by the love of a nation.

But on last year’s anniversary amid the annual outpouring of message after message of support, her thoughts kept returning to Mr. Sidhu, who was sentenced to eight years in prison and is now facing deportation to his native India.

“I was like, I bet you no one ever thinks about them,” Ms. Haugan says of her decision to send off an email to Mr. Sidhu’s wife.

It was short – just to say she was thinking of them, she says: “As much as my life changed that day, so did his. I just think someone needs to kind of remember them on that day, because ... they’ll never be the same either.”

Her defining moment resonates for many as the nation asks itself whether it, too, can find mercy for Mr. Sidhu as he fights against deportation and for a chance to stay in Canada despite what he did.

The collective grieving over the Humboldt tragedy still occupies outsize space in Canadian thought. Many continue to blame the driver who caused it all. Others, including victims themselves, say Mr. Sidhu is serving his time and that deportation is essentially a double punishment, a law etched in a “tough on crime” era that is inconsistent with Canada’s identity as a tolerant nation.

As the fifth anniversary of the catastrophic crash approaches, the notion of forgiveness – as Canada weighs whether it will find a place for Mr. Sidhu or reject him outright – remains a fraught value. Exalted for its healing potential, it can also amplify grief and blame.

“It is such a tragedy because both sides are so compelling,” says Alice MacLachlan, a philosophy professor at York University who studies apologies and moral repair. “I have a mystified admiration for parents who have forgiven him and complete understanding for those who haven’t.

“At the same time,” she adds, “this is someone who did something unbelievably awful but took full responsibility for it and accepted the harshest possible sentence ... and because of his citizenship status, which isn’t anything about who he is as a person, is much more vulnerable to the state as a result.”

Mr. Sidhu had only been on the job as a semi driver for three weeks as he rolled through the flat landscape of farms and prairie, loaded with 900 bales of peat moss. He’d gotten his commercial license to help put his wife, Tanvir Mann, through dental hygienist school – and the crash happened during his first week driving alone.

There is no question of fault. As he drove toward the intersection with Highway 35, where the Humboldt team was heading to playoffs, he was fixated on the tarps behind him, flapping over his cargo, and failed to notice – in clear afternoon daylight – five signs signaling the intersection, including the 4-foot-wide stop sign itself, with a flashing red light.

As Mr. Sidhu crossed into the highway intersection, the Humboldt bus, which had no stop sign, could not avoid the collision. In addition to those killed – the youngest just 16 years old – 13 others were injured. Some still can’t walk today.

Mr. Sidhu was convicted of 16 counts of dangerous driving causing death and 13 counts of dangerous driving causing bodily harm. In giving him eight consecutive years in jail – an unprecedented sentence for a collision that was not deliberate or involving impairment or distraction like using a cellphone – Judge Inez Cardinal said she was accounting for the magnitude of harm done.

“The loss of those killed and injured is staggering,” she wrote in her decision.

The crash generated an immediate global outpouring. A local hairdresser in Humboldt started a GoFundMe page; within days it generated $15 million (Canadian; U.S.$11 million), one of the largest sums in crowdfunding history. The little town of Humboldt amassed so many letters of love, hand-stitched blankets, children’s thick crayon drawings, and signed hockey jerseys – totaling 11,000 items – it mounted everything in an art gallery (on the second floor, to allow community members to avoid reminders).

Anita Dahlgren’s son Kaleb sustained a traumatic brain injury and survived. From her tidy home in Saskatoon, her petite goldendoodle, Murphie, on her lap, she reflects on the support in the wake of the crash. She recalls “the compassion and the love ... and just feeling surrounded with goodness.”

Several years later, many question if “goodness” should be shown today to Mr. Sidhu.

He is not a Canadian citizen but a permanent resident. So when he was sentenced to a term of imprisonment of more than six months, his chances of staying in Canada were put at risk. His immigration lawyer Michael Greene is fighting back.

Mr. Sidhu, who arrived in Canada in 2013, has stood as a sympathetic character from the start. He pleaded guilty to all charges laid against him, to avoid a trial and more harm to the families, even though he could have had an opportunity to plea-bargain, Mr. Greene says.

Families recall Mr. Sidhu’s clear remorse as he looked them straight in the eye when they read their victim impact statements – amid tearful descriptions of lost potential and rage, during which the notion of forgiveness on both sides took center stage.

“I despise you for taking my baby away from me,” one father said in a transcript published in the Saskatchewan press. “You don’t deserve my forgiveness.” Ms. Haugan, who publicly forgave him at that hearing, recalls the way he held his head up and looked each family in the eye. “It didn’t matter whether it was one like mine, ... or one that was incredibly angry and telling him he basically didn’t deserve to live,” she says. “I think it was just to me, it was so respectful.”

A Journey Without Judgment

One community’s struggle to come to terms with enormous loss became a powerful story about forgiveness – including of people not quite ready yet to forgive. That made it the most universal of stories. Reporter Sara Miller Llana spoke with host Clay Collins about her process, and about producing the hardest story she’d ever done.

Mr. Sidhu, who was granted day parole in July, and his wife Ms. Mann declined an interview request through their lawyer, in part because they’ve been criticized for doing more harm when they speak to the media and because of ongoing civil litigation against them, Mr. Greene says.

Ms. Mann, now a Canadian citizen, started an online campaign in August to help fund their legal fight to stay in Canada, calling her husband “the best man I know.” It has generated about $45,000 (Canadian; U.S.$36,600) – and some backlash. “Canada does not want you here and the fact that people are contributing to this is absolutely ridiculous,” reads one comment.

But most leaving donations from $20 to $500 have left the couple messages of support: “I cried that day, like every other Canadian. ... No one will ever forget that day ... but forgiveness is a gift you give to yourself.” “Stand firm with the knowledge that there are Canadians who have compassion.”

In March 2022, the Canada Border Services Agency referred Mr. Sidhu to the immigration board to proceed with deportation without the right to appeal. Mr. Greene is now requesting leave in the immigration case – or a chance to argue in federal court to appeal the decision. “Leave” is granted in only a minority of cases, he acknowledges.

The right of appeal in deportation proceedings was curtailed over the past two decades. Under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act of 2001, any foreigner receiving a sentence of two or more years lost the right to appeal, and then under the Conservative government of Stephen Harper in 2013, the threshold was reduced to six months. That’s a low ceiling that could include an offense as minor as smashing a window during an anti-globalization protest, says David Moffette, a professor studying the intersection of immigration and criminal law at the University of Ottawa.

Under criminal law, a person can’t be punished twice. Deportation is legally classified as an administrative procedure. But in reality it is understood as punishment, argues Dr. Moffette: “It’s a form of exile as a criminal punishment.”

He believes this case could become a test in which the country examines the fairness around the appeal system for foreigners. The process has received scant attention in part because it affects so few people, Dr. Moffette says. Roughly 1,000 removal orders are issued for serious criminality a year, according to government data. So it’s simply not been on the radar, he says, until now.

“I’ve been practicing now for close to 40 years, and this is probably the most difficult case on many levels that I’ve had,” says Mr. Greene. “I think forgiveness and second chances are a big part of our history and our culture. And I would like to see that reflected [here].”

Forgiveness is a process, but sometimes it can be encapsulated in a single moment.

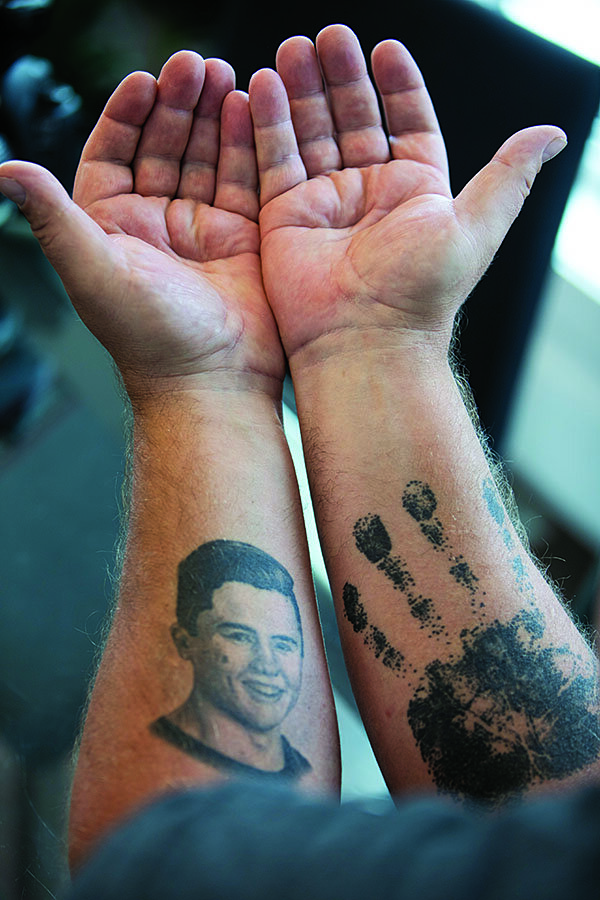

For Scott Thomas, that moment came in the back office of a makeshift courtroom at a community gymnasium in Melfort, Saskatchewan, where families of the Humboldt tragedy read aloud their victim impact statements in 2019, almost a year after the crash.

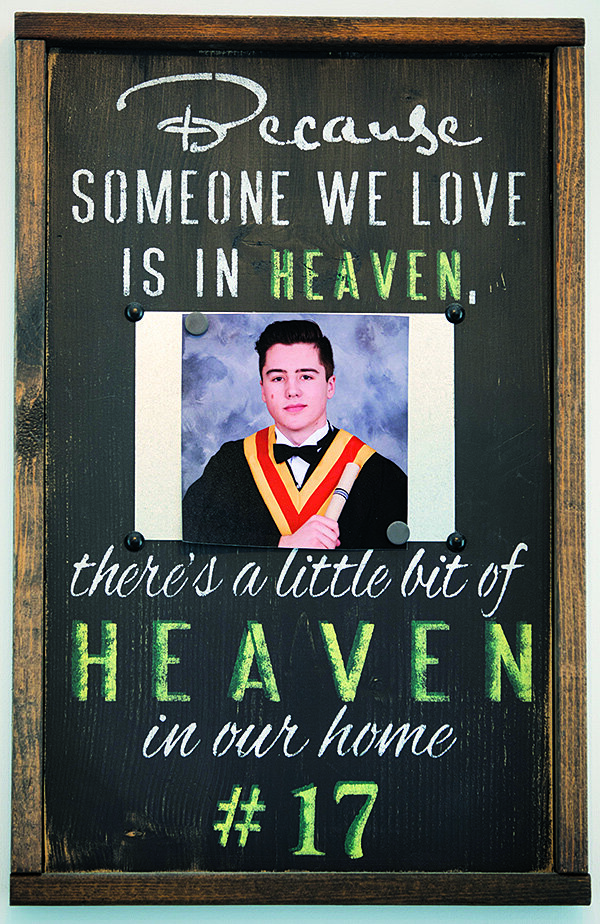

Scott and Laurie Thomas lost their son Evan in the collision. Their suburban Saskatoon home is a sanctuary to a child they remember as selfless with a sophisticated sense of humor. The landing on their stairwell is decorated with the first pair of skates he ever wore on the ice at age 2 – and the last, at age 18.

“I walked into the [courtroom] space, and Jaskirat immediately fell down on one knee and grabbed both my hands and just started weeping like a little baby. He was just bawling,” says Mr. Thomas, a chiropractor who cuts a large figure. His arms are tattooed with signs of Evan, including an inky handprint that was stamped at the funeral home so that the father would have a “piece of him alive” forever.

“I don’t know how long I let him stay there,” Mr. Thomas recounts. “But then I just grabbed him by the shoulders and picked him up, and we hugged each other. ... It felt to me like a father hugging his son. And as I was hugging him it was like, ‘Dude, what did you do? You should have known better’ type thing, right? It felt like I was hugging my boy and my heart broke for him, and I know his heart was broken, too.” He even handed him his cellphone number in case Mr. Sidhu ever needed it.

The Thomases haven’t spoken to Mr. Sidhu since. But when his lawyer, Mr. Greene, asked them to submit a letter to help fight deportation, neither hesitated.

Mr. Thomas calls deportation “the easy way out” for the nation – its politicians and the trucking industry. In fact he often imagines taking the stage with Mr. Sidhu – the two fighting together for safer roads and stricter rules for truck drivers.

Mandatory training for commercial drivers, for example, was not in place in the province at the time of the crash.

“I’d like to get in front of some decision-makers and have him lay out how ridiculously easy it was for him to get behind that truck, and then for me to kind of take over the conversation and say, ‘This is the result of that decision.’”

The couple know that they are on a journey different from that of many other “angel families,” as they call themselves. They can hardly explain it, except that they have a deep conviction that it is Evan himself guiding them, and that the freeing nature of forgiveness, for them, must mean they are on the right path, says Ms. Thomas.

It’s enabled them to put all of their energy into their son’s legacy.

“Part of why we forgive is because we can hear him telling us that this is the right thing to do,” she says. “I think the hardest part for me is five years later, I don’t want people to forget how great my kid was.”

But forgiveness is an unwelcome conversation among many in the group – and no place more so than in Humboldt.

On a frigid night last November, locals gather in the noisy brightness of the Elgar Petersen Arena to see the Broncos face off against the Notre Dame Hounds. Most of the Broncos come from elsewhere – as is the case on rosters of junior teams across western Canada, full of aspiring university or professional players.

Each season the players become part of the fabric of this 6,000-strong community, billeted in family homes, working at the local Boston Pizza and supermarket, and the youngest players attending the local high school. They help shovel snow, organize floor hockey for community members with disabilities, and walk shelter dogs weekly.

The tragedy remains front and center here. At the entrance to the ice, banners with the names of the victims hang from the pillars. The team jerseys were redesigned with the word “Believe” on the sleeve – a nod to late coach Darcy Haugan’s motto that he hung on a yellow kick plate in the locker room before the 2018 playoffs (a banner that then-assistant coach Chris Beaudry took to the hospital when the boys were recovering, sending it home only when the last player was released 11 months afterward).

Like the 2022-2023 team, the community focuses on moving forward because the subject of Mr. Sidhu is divisive, says Humboldt Mayor Michael Behiel.

“We don’t have as many of those discussions in public because they’re such controversial subjects. Everybody has an opinion, and it goes both ways. It ends up creating more controversy and more hard feelings than it’s resolving,” he says. “So it’s more important that we focus on healing.”

And many have put their efforts toward just that – advocating awareness about organ donations or for stricter rules for roadways and the trucking industry. When another tragedy befell Saskatchewan last year in a nearby Indigenous community – 11 people were killed in a knife rampage just 75 miles north – two of the mothers who lost sons in the bus crash quickly mobilized, delivering donated paper products, meats, and vegetables out of people’s gardens.

Broncos survivor Kaleb Dahlgren wrote the book “Crossroads: My Story of Tragedy and Resilience as a Humboldt Bronco,” a national bestseller and tale of resilience that he has taken to stages across Canada. He also founded an advocacy organization called Dahlgren’s Diabeauties for children diagnosed with diabetes, as he was. He had to give up dreams of playing competitive ice hockey – he can’t even jog across a street to make a walk light anymore – but he says he never asks himself “why.”

That’s not to say it’s easy – he talks daily with teammates from the Broncos who haven’t recovered from brain injuries. And he carefully avoids the subject of “forgiveness” because it’s too hard on some families.

“It took me a while to accept and understand that nobody heals the same way and that’s OK – that it’s completely OK to heal your own way and there’s no right or wrong way,” Mr. Dahlgren says.

The value of forgiveness is often considered crucial to moving forward – a belief as old as the Bible that took particular hold in public discourse during the 20th century.

But it can sometimes compound grief.

In Humboldt, under the media spotlight, it almost felt like a tool of coercion to some parents. Many refused interview requests by the Monitor, particularly on the subject of forgiveness, which they say paints Mr. Sidhu as the victim and themselves somehow as the ones at fault.

“Not all the parents were against forgiveness. But not all the parents were on board either,” says the Rev. Joseph Salihu, the priest at the Roman Catholic parish of St. Augustine’s in Humboldt at the time of the crash. “And it was difficult for them. They were not prepared, and no one should place a value judgment on that.”

The expectation of forgiving is not always applied equitably, says Dr. MacLachlan, the philosophy professor.

“We are uncomfortable with the idea of an unforgiving victim, because it’s almost like there’s something wrong or problematic or a sort of failure to be self-actualized in remaining angry,” says Dr. MacLachlan. “There’s much to admire about forgiveness. There can be something really important in refusals to forgive.”

It gets even more complicated when multiple families are involved, says Everett Worthington, a professor of psychology at Virginia Commonwealth University.

He says forgiveness is just one way that those grieving can reduce what he labels the “injustice gap,” but it’s not the only way. That gap can be reduced with justice, divine justice, forbearance, and acceptance, too.

“Forgiveness is a choice that we can make, and is only one of the ways that we can deal with this lingering sense of injustice,” he says. “What I always say to people is not everybody has to forgive, and that takes a lot of the morality out of it ... because people feel very resentful if you suggest that they have to forgive. They may not want to forgive.”

He adds, “We shouldn’t expect them to be in the same place.”

Those speaking out against Mr. Sidhu’s deportation say they worry about the pain it causes others. Mr. Beaudry, the assistant coach who was behind the bus in his own car when the crash happened and continues to work to overcome trauma, says that he faced Mr. Sidhu at his sentencing. They hugged each other. “And then he broke down, and him and I just hugged. And his wife came in, and hugged us, and we just held each other. And it was like I knew when I let go of him. He was going to jail. ... I was going back to my mind that was still angry and in pain and stuff. But when we were holding each other, everything felt safe.”

He says he knows these words might directly anger some families, but the stakes of the deportation are too high to keep silent, he says: “I don’t want to see them in pain. It’s never my intention. But I cannot not say what’s real for me. I’m not going to keep my voice quiet.”

Ms. Haugan, whose two boys were just 9 and 12 when they lost their father, remembers feeling plenty of rage. Her first victim impact statement was essentially an angry rant. But then, sitting at her kitchen table, she put her pen down midsentence.

Guided by faith, the values she and coach Darcy Haugan instilled in their household, and by her sons whom she didn’t want burdened by anger, she committed to forgiveness. “It was like this huge weight was lifted off me, like I didn’t have to find a reason, I didn’t have to find someone to blame.”

At first forgiveness was a daily choice: “For a while, I had to kind of think about it consciously. And I had to say it every day: ‘I’m not going to be angry. I’m not going to go down that road.’”

Eventually she understood she wanted to distinguish between the commitment she made to forgive and putting it into action. That’s why she’s offered, in whatever way she can, to help Ms. Mann and Mr. Sidhu find a happy future – in Canada.

“It’s easy to say that you forgive him. But it’s maybe a little bit harder to actually, genuinely want good for him and want the best for him and to be able to live that out,” she says.

“My personal opinion is that deporting them does no good. What purpose does it serve? It doesn’t serve a purpose. Like Darcy’s gone. We’re trying to live our lives the best we can. And that’s what I want for them, too.”

Essay

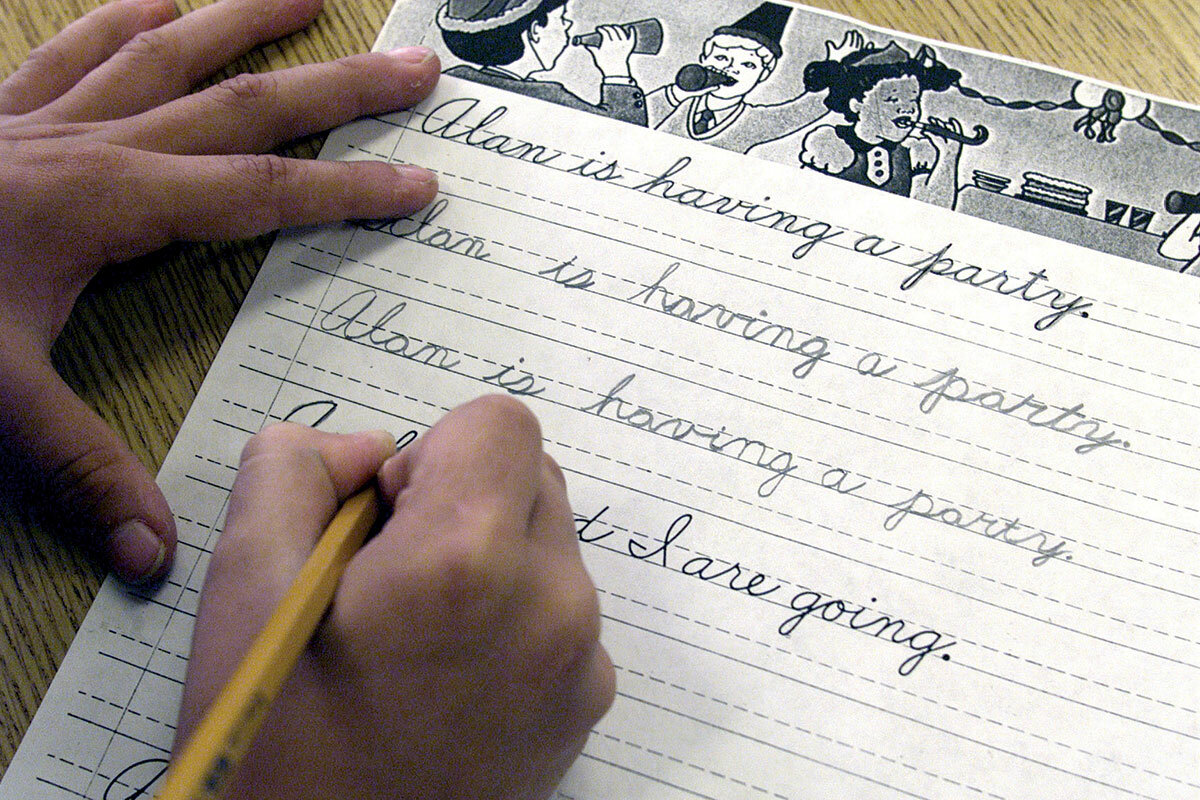

A curlicue of hope for cursive writing

Sometimes the beauty of a thing is obscured by the fact that one is obliged to learn it. It’s a joy to see a child embrace a skill that used to be required – cursive handwriting – just because they like it and it’s “weird.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Sue Wunder Contributor

Cursive was an obligatory lesson in my day. Connecting all the letters in a word in a wobbly flow was fun for me. I was a natural.

Cursive was no longer required when my grandson entered school. But one day when Connor was about 8, he watched me pen a letter to a friend.

“How do you do that?” he asked, his brow furrowed. “Can I learn it?”

Sports were Connor’s passion. He hadn’t shown much interest in school except for art class, where he excelled. Library books with cursive exercises were borrowed, and Connor bent over them with a concentration normally reserved for console games.

When he turned in his first assignment written in cursive, his teacher called me up: “How did he learn that?”

Connor didn’t have to learn it. So why had he, I asked him recently. “It was just weird, different,” he said. “I wanted to do it.” It was faster than printing, too, leaving more time for sports.

Cursive is old-school. But as an object of study, it wouldn’t be out of place in art class, in history class, or even in the free-flowing quiet of a desktop – an actual desktop – at home.

A curlicue of hope for cursive writing

I can still see and feel the sheets of white, blue-lined paper on which I learned cursive writing. Cursive was an obligatory lesson of early education in my day. Connecting all the letters in a word in a wobbly flow and with my own individualistic slant struck me as excellent fun, and I was a natural. I hardly recall printing, once I’d learned to write.

Cursive was still taught when my son entered elementary school, but was no longer required by the time my grandson entered school. Computer keyboards had supplanted handwriting, and children took to them swiftly.

Grandson Connor was soon coaching me on computers’ advantages and possibilities. Cursive was old-school.

But one day when Connor was about 8, he watched me as I penned a letter to a friend. “How do you do that?” he asked, his brow furrowed. He might well have been puzzling over an illuminated medieval manuscript.

I was taken aback. How, indeed? I’d been taught, I said, and I’d had lots and lots of practice. “Can I learn it?” he asked.

Sports, especially soccer, were Connor’s passions. While he did enjoy school, he hadn’t shown much interest in anything but art class, where he excelled.

Art class was an ideal launch point: He was already into the creative flow of a pencil or crayon on paper. Library books with cursive exercises were still to be had, and he began bending over them with a concentration normally reserved for console games and Pokémon cards.

When he turned in his first school assignment written in cursive, his teacher called me up: “How did he learn that?”

To me, learning cursive is like learning to pedal a bike or glide into turns on skis. Once you have it down, it’s a lasting skill.

Connor saw cursive as a compelling new art form. He didn’t have to learn it, which may have helped to open his portal of interest. When I asked him recently what he remembered about his boyhood fascination with cursive, he said, in his laconic way: “It was just weird, different. ... I wanted to do it.”

I didn’t recall which teacher had commented on his first cursive paper – and neither did he, because “so many of them said I had really nice handwriting.” He didn’t do it to impress. He did it because he wanted to.

Connor persisted. He evolved his own handwriting style and flow. He also found that cursive was faster than printing: It saved him time for things like soccer. Printing was to cursive what tiptoeing across a frozen pond is to ice-skating. He was hooked, and he continued to invent and embellish his script.

Cursive may not be integral to school curricula any longer. We are where we are, now, in the arc of human communication. But I hope cursive handwriting continues to attract and engage children, at least some of them, the way it did my grandson – with no more prompting than seeing someone use it to fill a sheet of paper with news for a friend.

As an object of study, script writing wouldn’t be out of place in an art class, in a history class, or even in the free-flowing quiet of a desktop – an actual desktop – at home.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The bonds that earthquakes can’t shake

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Within hours after the earthquakes in Turkey and Syria early Monday, more than 60 nations pledged support. The swift international response offers a counterpoint to fears that the world is increasingly divided by conflict. Yet at the earthquake’s epicenter, the Turkish city of Gaziantep, another lesson is on display, one that shows humanity need not be bound by ethnic or sectarian identities.

Gaziantep is a thriving city of Kurds, Syrians, and Turks – communities that have faced constant division elsewhere in the region. Over the past decade, the city welcomed half a million Syrians displaced by a war. City officials made a decision to see the migrants as a resource rather than a burden – and as a catalyst for improving services.

That social cohesion is now at work in Gaziantep. The city’s mosques and many civic venues have been opened to everyone. “Municipal workers have been distributing water, bread and warm rice,” writes CNN reporter Eyad Kourdi. Or as the city’s mayor, Fatma Şahin, says, “We are the guardian of all our residents,” with a special obligation to migrants.

Cinder blocks may crumble. But a community’s compassion, empathy, and inclusion are less easily shaken.

The bonds that earthquakes can’t shake

Within hours after the devastating earthquakes in southern Turkey and northern Syria early Monday, more than 60 nations pledged support. That compassion even reached across enemy lines. Israel has said it would send aid to Syria. Russians and Ukrainians living in Turkey are working together to assist Turkey’s most damaged cities.

The swift international response offers a counterpoint to fears that the world is increasingly divided by conflict and competition. Yet at the earthquake’s epicenter, the Turkish city of Gaziantep, another lesson is on display, one that shows humanity need not be bound by ethnic or sectarian identities.

More than 10,000 years old, Gaziantep is a thriving industrial city of Kurds, Syrians, and Turks – communities that have faced constant division and conflict elsewhere in the region. Over the past decade, the city welcomed half a million Syrians displaced by a civil war. Residents and city officials made a conscious decision to see the migrants as a resource rather than a burden – and as a catalyst for improving services like water, health care, housing, and education for everyone.

That social cohesion is now at work in Gaziantep’s rescue and recovery from the earthquake. The city’s mosques and many civic venues have been opened to everyone. “Municipal workers have been distributing water, bread and warm rice,” writes CNN reporter Eyad Kourdi from the city. Or as the city’s mayor, Fatma Şahin, told the World Urban Forum last June, “We are the guardian of all our residents,” with a special obligation to migrants.

Urban experts have taken note. “Gaziantep addressed an important question: Do refugees cause social, political, and economic destabilization?” wrote Önder Yalçın, the city’s former director of migration, in an essay for the German Marshall Fund. The city concluded that destabilization was the result of poor leadership rather than refugees. That insight led to a strategy to emphasize social justice and human rights.

“We are aiming for social cohesion, because Turkish and Syrian people are going to live together here, and if you only help Syrians, there is going to be tension,” Mr. Yalçın told The Guardian in 2019. “We said: ‘When you help Syrians in the same neighborhoods where Turkish people have the same needs, you have to help them, too.’”

That approach leads to shared uplift. “If inclusion is managed effectively and at all levels of a community, it can create a lot of wealth,” notes Roi Chiti, the coordinator for the Inclusive Cities, Communities of Solidarity project, in a Center for Global Development blog post.

In a region already torn by several conflicts, the earthquakes have compounded existing humanitarian crises. Yet as the recovery and reconstruction begins, leaders in the devastated areas can look to Gaziantep. The mayor, Ms. Şahin, was recently ranked the third-most successful mayor in Turkey in a survey. Cinder blocks may crumble. But a community’s compassion, empathy, and inclusion are less easily shaken.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Know the truth, find freedom – a promise

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Bobby Lewis

We’re all divinely empowered to discern the spiritual facts that bring about healing – as a man experienced firsthand after an alarming breathing difficulty arose.

Know the truth, find freedom – a promise

I was out on a backpacking trip when I started to have difficulty breathing at night. When I would fall asleep, I would stop breathing and wake up with a start. It was concerning, so I began doing something I’ve consistently found helpful in times of trouble: praying about it.

There’s a well-loved teaching of Christ Jesus that says, “You will know the truth, and the truth will make you free” (John 8:32, Revised Standard Version). This encourages us that we can find freedom from things that are discordant by knowing the truth about God, divine Spirit, and by understanding our identity as Spirit-created and therefore spiritual. Created in the image and likeness of Spirit, we reflect the wholeness and harmony of the Divine.

As I prayed, inspiration came that Jesus’ teaching wasn’t only instruction about what we should do, but a promise – a promise about what God is doing. The presence of God, the goodness of God, the love of God, are ever active.

I felt in that moment an assurance that God, Truth itself, would reveal whatever truths about God and myself I needed to know in order to be free from this condition that was interrupting normal rest. I started to hear the passage in thought with a comforting emphasis on “will” – “You will know the truth, and the truth will make you free.”

Referring to another of Jesus’ teachings, Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, writes in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “Jesus’ promise is perpetual” (p. 328). Science and Health also assures, “The promises will be fulfilled” (p. 55). It’s not a question as to whether or not God will reveal truth to us. It’s a promise, because infinite Truth reveals itself continually.

What I was receiving on that backpacking trip was the feeling of God’s presence and healing love that extended beyond just acknowledging those things. It was a certainty of the allness of divine good, of Love and Truth. As I prayed, this certainty grew, and there was simply no more room for fear about the symptoms or what they meant for my health.

And I did find freedom. The symptoms that for a number of nights in a row had been uncomfortable and frightening, ended. I was able to rest normally, hike, and enjoy the time spent moving through those beautiful mountains.

“This awakening is the forever coming of Christ, the advanced appearing of Truth, which casts out error and heals the sick,” is the way Science and Health characterizes this kind of experience (p. 230). The Christ, Truth, reveals to us the ever-presence of Spirit, the healing all-power of divine Love, the divine Principle that is as fully available and accessible for each of us right now as it was for those to whom Jesus ministered.

Divine Truth is a change agent that quiets fear and restores well-being. It is liberating to know that divine Love is loving us in ways that reveal to us the truth of our intact spiritual wholeness. Opening our hearts to receiving the truths that God is imparting, moment by moment, brings freedom.

Here’s a poem inspired by these ideas and this experience:

Set free

“Know the truth”

an instruction, yes

a promise too? yes

an instruction

to affirm the truths

already received

to hold sacred

in prayer

what is knowna promise too

that just what is needed

in this moment

about the Divine

about me

about them

about all

will be revealed

and receivedthe promises

will be

fulfilled.

A message of love

Leaning in to help

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when we talk to women whose lives have been turned upside down by Taliban decrees.