- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- After quake, Syrians lost outside aid. They’re working to help themselves.

- Nicaragua prisoner release: Win or loss on human rights?

- An Arkansas town pins its hopes on a teen mayor

- ‘You can’t heal what you don’t reveal’: Archives as a path to justice

- With after-school center, trans activist Sumi Das seeks kinder future

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

With mysterious objects downed, a story beyond the usual bounds

I’ve spent much of my career covering the Pentagon and writing stories about military aviation. Yet the news of recent days, with the U.S. Air Force downing four objects floating over North America, is a story beyond the bounds of anything I have ever encountered.

I’ve never heard an official say, in all seriousness – as White House spokesperson Karine Jean-Pierre said yesterday – that in a particular event, extraterrestrials were not involved.

“Wanted to make sure the American people knew that,” she said.

OK. So what is going on?

On Tuesday Biden administration officials briefed the Senate on what they know now. They remain confident the first object shot down was a Chinese spy balloon. The other three, they don’t know.

They haven’t recovered debris from them. Nor did fighter pilots who shot them down get a good look.

Imagine a supersonic jet – an F-16 can hit 1,300 mph – flying by a floating blob that’s barely moving. Audio from the pilots who intercepted the object over Lake Huron reveals they struggled with visual identification.

“Looks like something. ... It’s hard to tell, it’s pretty small,” said one.

Senators said a crucial question remains where these objects are coming from.

A range of entities, from companies to academic organizations, operate objects at high altitude for research. Is that what readjusted U.S. radars are now seeing?

Among the answers Tuesday’s briefing did provide was that “this has been going on for years,” said Republican Sen. John Kennedy of Louisiana.

“The only thing I feel confident saying right now is that if you are confused, you understand the situation perfectly.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

After quake, Syrians lost outside aid. They’re working to help themselves.

The Feb. 6 earthquake in Turkey rocked rebel-held northwest Syria as well. Locals are doing the best they can to deal with the disaster, but aid is in short supply due to the region's isolation.

When the earthquake hit on Feb. 6, the displaced Syrians living along Syria’s northern border with Turkey had no choice but to fend for themselves.

Many of the 4.5 million people who live in the rebel-controlled strip of land have moved homes more than once, fleeing their country’s 11-year civil war. They depend entirely on United Nations-coordinated international aid coming across the border.

The earthquake brought such aid to a complete halt – and it only resumed, partially, days later.

This is partly because the Syrian nongovernmental organizations that implement the distribution of the aid, both those in Turkey and those in Syria, have themselves been hard-hit by the earthquakes.

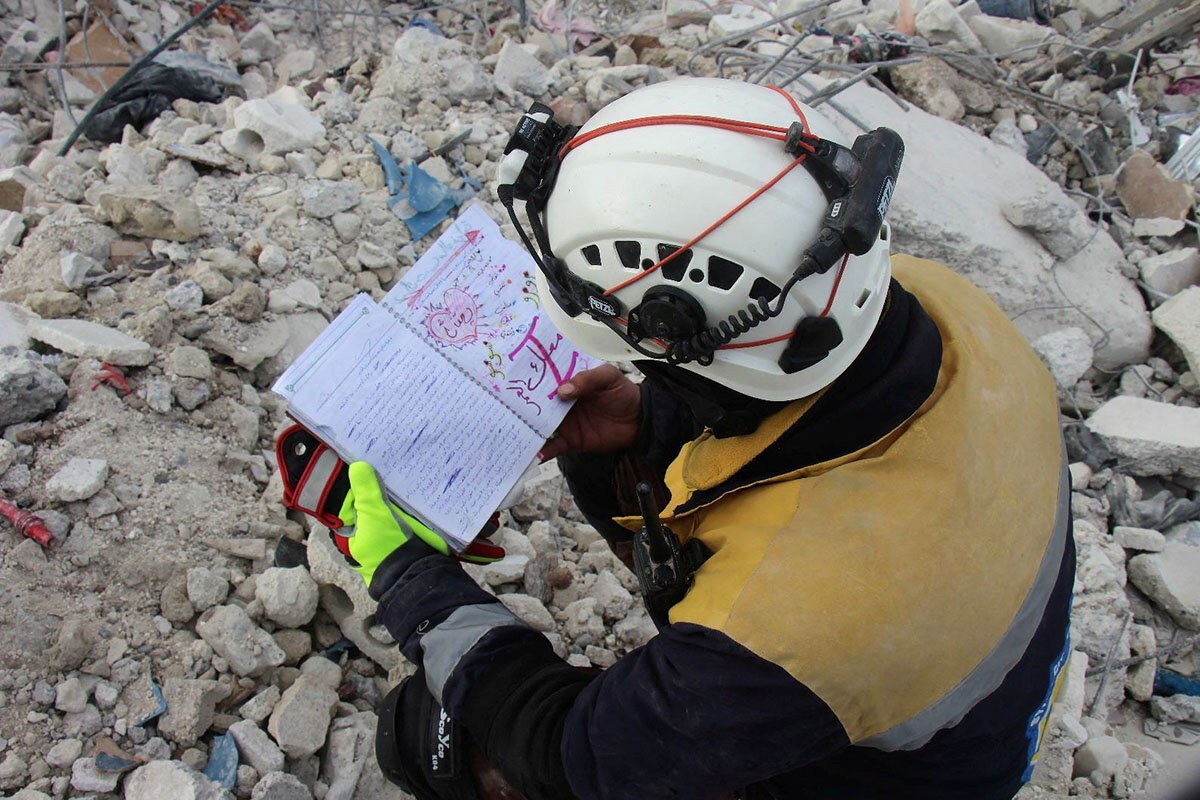

But as has been the case in the aftermath of Russian or Syrian air strikes, barrel bombs, and chemical attacks, it has been the White Helmets – volunteer rescue workers – who were the first on the scene, with many in the community offering what help they could.

“We saw great things from the Syrian community,” Mohammed al-Shebli, the White Helmets’ spokesperson, says. “All of them chipped in in this crisis. Some gave us fuel. Some gave us their cars. They gave us supplies.”

After quake, Syrians lost outside aid. They’re working to help themselves.

For a full week, Thamar Abu Nayla and a group of fellow volunteers scrambled through the rubble of Jandaris, a town in northwest Syria shattered by the recent earthquakes, using the few tools they had: picks, shovels, and their bare hands.

“Jandaris is devastated,” says Mr. Abu Nayla, in a telephone interview. “All the buildings are destroyed. All the streets are destroyed.” Those who did survive, he says, were left facing subzero temperatures and a glacially slow flow of international aid.

“We didn’t ask for food aid or water. We wanted [equipment to] help save people in the first 48 hours,” Mr. Abu Nayla explains. “Those who did not die from the impact of rubble died from the cold. People feel like the whole world abandoned them.”

A top United Nations official agrees. “We have so far failed the people in Northwest Syria,” U.N. Undersecretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Martin Griffiths said over the weekend. “They rightly feel abandoned, looking for international help that hasn’t arrived. My duty and our obligation is to correct this failure as fast as we can.”

Many of the 4.5 million people who live in the rebel-controlled strip of land along Syria’s northern border with Turkey have moved homes more than once, fleeing their country’s 11-year civil war. They depend entirely on United Nations-coordinated international aid coming across the border.

The earthquake brought such aid to a complete halt – and it only resumed, partially, days later.

This is partly because the Syrian nongovernmental organizations that implement the distribution of the aid, both those in Turkey and those in Syria, have themselves been hard-hit by the earthquakes. Some of their staff members were killed, many others have lost their homes and operations have been badly disrupted. Roads in the region are not always passable.

But the aid holdup is primarily a result of diplomatic wrangling. The Syrian government and its ally, Russia, have refused to allow U.N.-coordinated humanitarian aid to cross into northwest Syria except through one border point, at Bab al-Hawa.

On Monday, in negotiations in Damascus with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, Mr. Griffiths won his agreement to a deal that will open two more crossing points for three months.

For Tarek Alikhwan, who runs a Syrian NGO working in Turkey, this is welcome news but not enough. “From the humanitarian perspective this is very good,” he says. “For sure it will make a difference for the people affected by the earthquake. This also shows how easy it is for Bashar al-Assad to just say yes to cross-border aid.”

Stephane Dujarric, spokesman for U.N. chief Antonio Guterres, said he was pleased that “all parties concerned in the conflict put politics aside.”

Fending for themselves

For the tens of thousands of displaced people in northwestern Syria, this is too little, too late. An estimated 5,700 people in Syria have died, the bulk of them in the rebel-held area, either from injuries sustained during the earthquake or from the cold since then. Graves are being dug faster than tents are being raised.

As so often in the past, as they fled the civil war, these displaced Syrians have had no choice but to fend for themselves. And as has been the case in the aftermath of Russian or Syrian air strikes, barrel bombs, and chemical attacks, it has been the White Helmets – volunteer rescue workers – who were the first on the scene. For many Syrians, the heroism and speed of that response stands in sharp contrast to lackluster international efforts.

Until Sunday, Mr. Abu Nayla and his motley crew focused on rescuing survivors from the rubble, but with little success. They managed only to save two families and, miraculously, a 3-month-old baby, still alive after 148 hours trapped in her crushed home.

But Mr. Abu Nayla has been able to use his pickup truck to distribute basic supplies donated by local people less hard hit than the residents of Jandaris. Mindful that survivors there have nowhere to cook, they offer canned foods, such as mortadella, cheese, and halawa, a sweet Syrian breakfast staple.

He says they have also manufactured and pitched four makeshift tents, using donated material and the skills of a local tailor and welder, because no tents are available at the local market.

“It’s nowhere near enough but it is what we can do,” Mr. Abu Nayla says. “People are giving everything they can to help. Those who have a little, give a little. Those who have more, give more.”

Mohammed al-Shebli, the White Helmets’ spokesperson, says search and rescue operations continue in some areas, even though no one has been found alive in the past 48 hours. Of the organization’s 3,300 members, about 2,600 specialize in search and rescue, but they lacked the equipment and fuel to operate on the necessary scale.

Under normal circumstances, White Helmet teams discourage onlookers from helping to pull people out of the rubble. But these have not been normal circumstances, and they sought help wherever they could find it.

“We need to speed up”

“We saw great things from the Syrian community,” Mr. Shebli says in a telephone interview. “All of them chipped in in this crisis. Some gave us fuel. Some gave us their cars. They gave us supplies.”

In the absence of sophisticated equipment such as CO2 sensors or rescue dogs, nervous neighbors combed the rubble in Jandaris, listening for signs of life. White Helmet and other volunteers worked round-the-clock to save those they could, and agonized hours sharing the final moments of those they could not rescue.

They took down wills, a dictated letter from a granddaughter to her grandmother, phone numbers, and personal messages, Mr. Shebli says, his voice full of frustration. “Imagine: You can see a person who is alive and hear that person, but you can’t help.”

Making matters worse, many of the individuals the White Helmets did manage to rescue from the rubble died later due to lack of proper medical care. Some have lost or risk losing limbs, among them Sham, a girl who survived with her siblings but lost her mother.

Mr. Alikhwan of the IYD International Humanitarian Relief Association shares the mood of frustration. But outside help can still make the difference between life and death, he says.

“Syrian NGOs are trying to respond to the situation, but we depend on international aid,” he adds, criticizing the slow pace of action from the international community when there are projects ready to go.

“There is a bit of help, but in such small amounts it is embarrassing,” he says. “We need to speed up the help, increase the volume, and facilitate cross-border aid deliveries.”

Nicaragua prisoner release: Win or loss on human rights?

Political exiles navigate two currents: the relief of safety against the loss of home. Prisoners released from Nicaragua to the U.S. must confront the limitations of what they can accomplish from afar.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega released 222 prisoners last week, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken praised it as a step “toward addressing human rights abuses” in Nicaragua.

The group includes high-profile politicians, journalists, activists, and students who spent months behind bars on trumped-up charges by the Ortega government before they were put on a plane and sent to Washington. Certainly for the prisoners and their families, relief abounds that they are now free. But they were also stripped of their Nicaraguan citizenship.

They now face the complicated duality of exile – relief in personal safety, or in some cases reuniting with family, contrasting with the challenge of losing a home and leaving others behind – and are likely to confront limitations in democracy-building with Mr. Ortega’s power consolidated.

“The release of the 222 people who were living under terrible circumstances for a prolonged period of time is a huge humanitarian gain,” says Richard Feinberg, professor emeritus of international political economy at the University of California, San Diego. “But, if you’re looking at the politics ... I think Daniel Ortega has rid himself of the leadership of the opposition; strengthening, not weakening, his authoritarian grasp on Nicaraguan politics.”

Nicaragua prisoner release: Win or loss on human rights?

Ulises Mendieta, a young Nicaraguan journalist, knows something about exile – particularly what can and cannot be accomplished living in it.

For nearly three years, he has helped build a Nicaraguan news site, collaborating with sources back home to cover national politics and share information beyond President Daniel Ortega’s party line. It’s work that puts sources – and his loved ones still in Nicaragua – at risk, but it allows him to push for a “free” Nicaragua, he says.

Now, many more will be faced with navigating how to advocate for democracy and freedom of information in the increasingly authoritarian Central American nation when living abroad. On Feb. 9, 222 Nicaraguans, including high-profile politicians, journalists, activists, and students, were sent into exile after months and sometimes years behind bars on often sham or trumped-up charges brought by Mr. Ortega’s repressive government. They were put on a U.S. charter flight to Washington, D.C.

As these individuals face the complicated duality of exile – relief in personal safety, or in some cases reuniting with family, contrasting with the challenge of losing a home and leaving others behind – they are also likely to confront limitations in democracy-building with Mr. Ortega’s power consolidated.

“The release of the 222 people who were living under terrible circumstances for a prolonged period of time is a huge humanitarian gain,” says Richard Feinberg, professor emeritus of international political economy at the University of California, San Diego. “But, if you’re looking at the politics ... I think Daniel Ortega has rid himself of the leadership of the opposition; strengthening, not weakening, his authoritarian grasp on Nicaraguan politics.”

There’s “no counterweight to the local government,” explains one Nicaraguan academic, who spoke on the condition of anonymity given the repercussions for critiquing Mr. Ortega’s government. “Even compared to other dictatorships in Latin America, local resistance is extremely weak in Nicaragua,” he says, adding that this weakness restricts how successfully Nicaraguans can push for democratic change from outside the country’s borders.

Mr. Ortega, a former revolutionary, rose to fame in the 1970s and ’80s after helping the Sandinista Revolution topple a decadeslong dictatorship. He went on to lead for 11 years following the 1979 overthrow. But since 2006, when he won the presidency once again, he has centralized power (even making his wife his vice president), chipped away at free expression, shuttered media outlets and nongovernmental organizations, and cracked down on political dissent, especially since anti-government protests erupted in the spring of 2018.

Many of the political prisoners released last week were arrested and charged in the lead-up to the widely discredited 2021 presidential vote. The broad arrests – and the exodus of many objectors – eliminated any semblance of competition for Mr. Ortega, ushering in his fourth consecutive term.

The U.S. has responded to the human rights violations by imposing sanctions on Mr. Ortega and his family, as well as against high-ranking government officials and the mining and gold sectors.

Many foresee a difficult year ahead, with economic growth projected at less than 2% amid growing inflation. Nearly 604,500 Nicaraguans fled between 2018 and 2022, half of that in 2022 alone, according to Nicaraguan news site Confidencial.

A win for human rights?

In this month’s prisoner release, as soon as they arrived in the U.S. the Ortega government stripped them of their Nicaraguan citizenship. Spain offered citizenship, and the U.S. has granted the individuals two years of humanitarian parole, allowing them to remain in the U.S. and apply for asylum, if they choose.

In a statement Feb. 9, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken praised the release as a step “toward addressing human rights abuses” in Nicaragua. But back home Mr. Ortega echoed a long-touted idea that anyone opposing his government was in the pocket of the U.S., saying Washington should “take their mercenaries.” Over the weekend, hundreds of thousands marched in Nicaragua, celebrating the “sovereignty of their country” and the expulsion of “the terrorists,” as state-run news sites referred to the former prisoners, parroting Mr. Ortega.

“This is a moment of great uncertainty,” says the Nicaraguan academic. “It would be a mistake to assume this is the first step to some great opening or loosening of the police state. It could just as well be the opposite; [Mr. Ortega] taking this as a first step toward tightening things further.”

The release took everyone by surprise, with relatives of former political prisoners in the U.S. rushing to Washington to embrace their loved ones. Many had believed they would never see their family again. Amid the relief and elation are questions around what happens next.

Few are hopeful for positive change inside Nicaragua in the short term. The government has spent the past several years “building out their security apparatus’ control throughout the entire country, adding to their networks of informants within Nicaragua,” says Kai Thaler, an assistant professor focusing on authoritarianism at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “It’s really, really hard to organize or engage in new protests, because people now know, ‘alright, even if I’m not a very prominent person, I can still wind up in jail, facing torture and mistreatment,’” he says.

On top of that, the government has all but erased civil society, closing more than 400 NGOs since the 2018 protests.

“It’s really bittersweet,” says Mr. Mendieta, the journalist, now with asylum in Costa Rica. “There’s the joy from the news of the political prisoners’ release, but at the same time, the realization that the regime has created an environment of self-censorship, and everyone feels its weight. You can’t say anything on social media, you can’t say anything to your neighbors. Even if Ortega were to go tomorrow, it will be hard to re-create a culture of freedom of expression and respect for human rights.”

For some, that is where the released prisoners and other Nicaraguans living abroad come in.

Activism in exile

Some are already speaking out. José Ricardo Muñoz López, a young political activist involved with the Nicaraguan Democratic Force who was imprisoned for four months, told Voice of America he plans to hold demonstrations against Mr. Ortega’s repression globally, demanding the release of remaining political prisoners in Nicaragua. But once his humanitarian parole expires in two years, he wants to “return to Nicaragua, to defend social justice,” he said.

“There is always diaspora activism and activism in exile. The problem for Nicaragua’s opposition for a while has been unity,” says Dr. Thaler. “Now the challenge is going to be, if they’re going to continue speaking out in exile, how that is coordinated, or what people see as potential options for still achieving political change inside Nicaragua.”

Mr. Mendieta says he doesn’t expect everyone who was exiled to commit to publicly fighting for Nicaragua’s future. Although he was never imprisoned, his journey out of Nicaragua came with its share of challenges. “They are in a vulnerable situation, and they need to first take care of themselves and their loved ones,” he says.

But “Nicaraguans have heart” and those forced to leave home “will always want a free Nicaragua,” he says. He expects that anyone, whether they’re exiled or make the difficult choice to leave, is going to “fight in his or her own way, to do what they can for the future of Nicaragua,” he says, “even if they aren’t super visible.”

Stepping Up

An Arkansas town pins its hopes on a teen mayor

Generation Z is stepping up in national politics and state legislature – and in this small Arkansas town. Instead of heading away to college, 18-year-old Jaylen Smith ran for mayor, and won.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

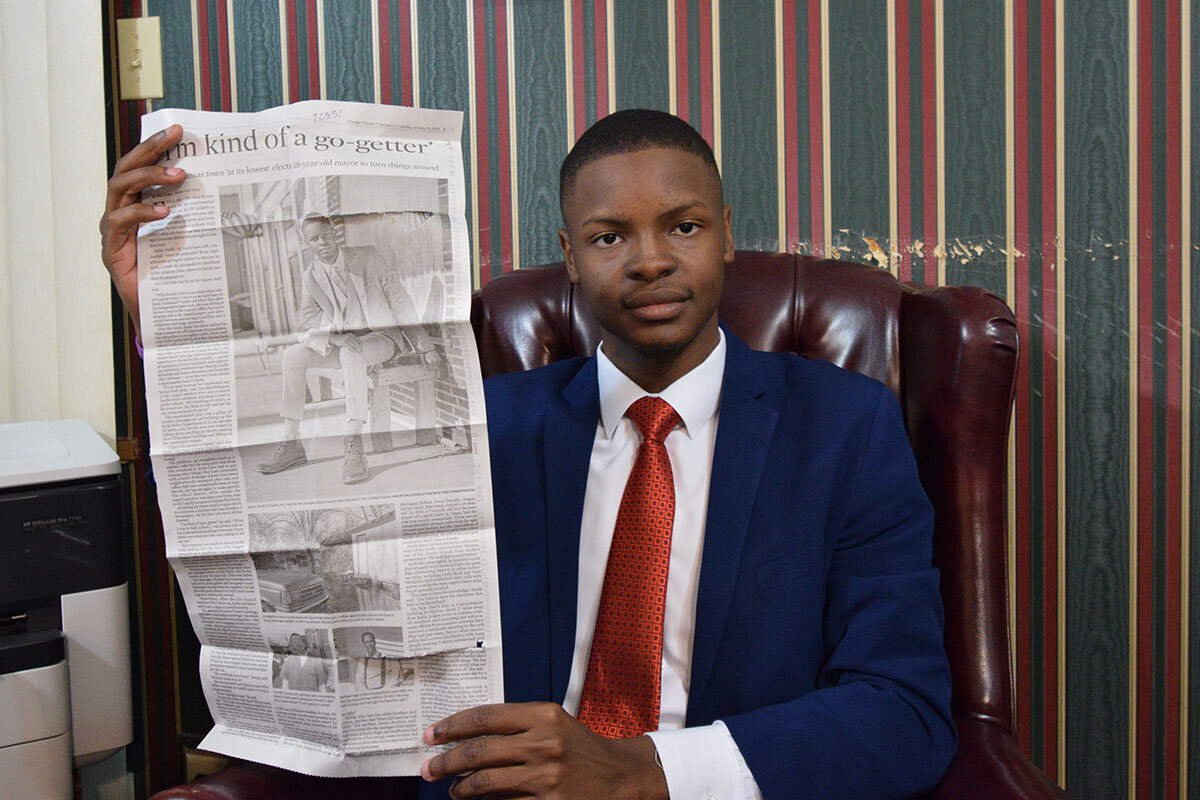

Jaylen Smith works with his door open to the street, an invitation to his town. Last year, the mayor of Earle, Arkansas, was a high school senior. Then he won a runoff election, pledging to staff police 24 hours a day, tear down derelict buildings, and bring back a supermarket.

He’s not the first teen mayor in the U.S. – Hillsdale, Michigan; Mount Carbon, Pennsylvania; and Roland, Iowa, are among cities that elected leaders right out of high school. But Mr. Smith is the youngest Black mayor in the country.

Mr. Smith is part of a growing number of civically engaged members of Generation Z, says Layla Zaidane, president and CEO of the Millennial Action Project. In the past year, the number of millennials running for office increased by about 57%, says Ms. Zaidane, while the number in Generation Z nearly tripled.

“Young people choosing to run towards our political system,” she says, is a result of the “twin forces of frustration that things aren’t better and a sense of agency that they can make it better.”

Outside, Mr. Smith can’t walk down the street without bumping into someone who – even if they’re raising a concern – can’t help hugging him, or telling him how proud they are of him.

The City Council meeting that night – Mayor Smith’s first – is standing room only.

He ends with a quote from the Bible to applause: “Let us not weary in doing well, for a new season we shall reap.”

An Arkansas town pins its hopes on a teen mayor

Many teenagers consider their wardrobes a statement of their identity. For 18-year-old Jaylen Smith, that means a suit instead of jeans and a backpack. Today, the new mayor of Earle, Arkansas, has dressed with special care: a navy two-piece suit, crisp white shirt, and brown dress boots. His tie is red.

Tonight, he will call the City Council to order for the first time as mayor. He’s also heading into Memphis – 30 miles away – to buy his own car, a Nissan Altima.

“If you want to get somewhere, you have to act and dress like it,” he says. “And that’s what I did.”

If he’s nervous about his big speech, it doesn’t show as he does his job from an office with decor from the mid-20th century, from the burgundy-and-green striped wallpaper to the fake fruit vines wrapped around the brass sconces. The computer on his desk may be the only thing that, like Mr. Smith, hails from the 21st.

He works with his door open to the street, an invitation to his town.

Whether he’s in his office, on the road, or stopping at a parking lot to pick up chicken salad – and pause for a selfie with the guy selling it – Mr. Smith is always on the phone. Dialing a number, he talks to a woman whose house just burned down. “Is there anything we can do for you,” he asks. He listens to her response, nodding, and promises he’ll call the Red Cross.

He’s not the first teen mayor in the U.S. – Hillsdale, Michigan; Mount Carbon, Pennsylvania; and Roland, Iowa, are among cities that elected leaders right out of high school. But Mr. Smith is the youngest Black mayor in the country, according to the U.S. Conference of Mayors. He won in a runoff election, pledging to staff police 24 hours a day, tear down derelict buildings, and bring back the supermarket that closed down a few years back.

Driving past Crawfordsville, a town about 15 minutes from Earle, he explains that his parents – as well as grandparents and cousins – lived there before moving to Earle, where he grew up, in 2000. Mr. Smith was born five years later.

Mr. Smith graduated from Earle High School in 2022. Instead of packing for college and leaving, he spent the rest of the year campaigning door to door and shadowing mayors around the state.

Perhaps more notable than Mr. Smith’s age is his choice not to leave Earle. As he tells Christopher Conway, his former high school counselor, “I always wanted to change my community before moving on to my next phase of life,” he says.

“That’s right,” agrees Mr. Conway. “Your goal is always to build up Earle.”

Earle, Arkansas, population 1,800, may seem frozen in time by a lack of money and a declining population. The sense of community buy-in and optimism is clear in the halls of the elementary and high schools, and the well-attended City Council meeting – with an agenda including reports from the police chief and the water and sanitation department, and a debate about zoning.

Tucked on the side of Highway 64, Earle boasts three dollar stores and two schools, and a small grocery store that’s been around since 1945. The number of abandoned buildings suggest that Earle has seen better days – that Mayor Smith is pledging to revive.

Earle rose out of the post-Civil War timber boom that gave life to so many other small towns dotted along Southern railroads. Today, the town is majority Black. But its painful history includes lynchings and a race riot over school conditions, not to mention its namesake, landowner Josiah Francis Earle, who was active in the Ku Klux Klan.

Eugene Richards, a photographer, writer, and filmmaker, found himself in Earle in the late 1960s as a member of Volunteers in Service to America. At the time, Earle was separated into white and Black, he says, “divided by the classic railroad tracks.”

Mr. Richards and several VISTA volunteers helped start a paper, Many Voices, which reported on Black political action and the Ku Klux Klan. He was friends with the Rev. Ezra Greer and his wife, Jackie Greer, civil rights activists who led a march protesting segregated schools in 1970. When the marchers were confronted by an angry white crowd, five Black marchers were wounded – including two women who were shot.

After that day, Mr. Richards says, “Time went on and things slowly changed.”

Mr. Richards, who compiled photos and interviews for a 2020 book about the town, says that while the violence of segregation may be in the past, Earle faces new challenges.

“There’s a weariness – the town is going down very fast,” he says.

As student government president for his last three years at Earle High School, Mr. Smith implemented tutoring programs and an advocacy committee for students with learning disabilities. He was also a student advocate for special education students, and dealt with his own learning disability while in school. Those activities taught him how to get resources from the state, he says. After a visit to Washington, D.C., for a mayoral conference, he’s optimistic about receiving more federal grants as well.

Mr. Smith is part of a growing number of civically engaged members of Generation Z, says Layla Zaidane, president and CEO of the Millennial Action Project.

In the past year, the number of millennials running for office increased by about 57%, says Ms. Zaidane. The number in Generation Z nearly tripled.

“Young people are choosing to run towards our political system and actually [put] their own hat in the ring,” she says, chalking that impetus up to the “twin forces of frustration that things aren’t better and a sense of agency that they can make it better.”

Between learning the ropes of public office and taking a college course online as he pursues his degree – one class at a time for now – Mr. Smith doesn’t have much free time.

His phone rings again. This is the part of the job he doesn’t like: being pressured for favors. In this case, he stands his ground over the open clerk position. Every applicant has to turn in an application, he says firmly. “I’m not going to hunt it down.”

Off the phone, he runs down his goals as mayor. He wants to improve public safety, including fully staffing the police department, currently at two full-time and four part-time officers; set up public transportation; and tear down those abandoned houses.

He’s already spoken with a local business that has agreed to help demolish houses, and he’s confident he’ll find resources to achieve the rest of his goals. “They’re there,” he says.

Back in Earle, he turns to answering correspondence, finding grants to apply for, and, of course, picking up the steady stream of phone calls on both of his cellphones. He starts working on another “first”: filling out a funeral resolution. After searching online to no avail, he picks up his phone and dials. “Hey Pop,” he says, taking a drink of Coke. “What did you tell me I need for a funeral resolution?”

That done, Mr. Smith turns to the next task. He asks a friend who just walked in, Lacordo Hemphill, for a favor. Can he run out and get him some Ritz crackers and a bag of spicy Doritos to eat with his chicken salad?

Mr. Smith may have the job and suit, but he still has the lankiness and appetite of a teenage boy, subsisting on chips and soda as he sorts through city paperwork and responds with patience to citizens’ complaints and concerns.

He pivots back to his computer monitor, as gospel music plays in the background.

While Mr. Smith, a Democrat, aspires to higher office, he says he isn’t focused on party politics. He attends local Democratic and Republican party meetings to “see how they both do,” he says.

Mr. Smith opens an envelope and a check falls out of the card inside. He dusts chip dust from his fingers and makes another call: “What do I need to do with checks that come in the mail?”

“I can’t accept money as an elected official,” he explains after. “But I can donate it to the city.”

Donald Russell, a retired truck driver, was skeptical when Mr. Smith announced his campaign. But after getting to know him, he has “high hopes.”

And Mr. Smith “has a lot of community support,” he says. “This is his city.”

His friend Mr. Hemphill says he’s excited to see a young person in local politics – maybe even more so than Mr. Smith himself. Now he’s more inclined to vote and go to community meetings, he says.

Outside, Mr. Smith can’t walk down the street without bumping into someone who – even if they’re raising a concern – can’t help hugging him, or telling him how proud they are of him, “Mr. Mayor,” the “good kid.”

Thirty minutes before the council meeting, Mr. Smith stands up, puts on his suit jacket, locks the door, and crosses the street to the council chamber. People trickle in after him – one asks to take a photo together. Every seat is full, and residents are standing at the back. Mr. Smith opens the meeting, occasionally leaning over to check next steps and procedure with his more experienced companions. Then he stands to deliver his speech, announcing his goals to fully staff all police shifts and institute a neighborhood watch program.

He ends with a quote from the Bible to nods, murmurs of approval, and applause from the room: “Let us not weary in doing well, for a new season we shall reap.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to clarify that Mr. Richards helped cofound the newspaper Many Voices.

‘You can’t heal what you don’t reveal’: Archives as a path to justice

How should history affect the future? The Riverside Church in New York is turning to its extensive archival collections not only for an honest assessment of its past but for guidance on its next steps.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Maisie Sparks Contributor

Among The Riverside Church’s archival collections are a Bible printed in 1493 and stained-glass windows from the 16th century. But just as valuable to the church, established in 1930, are its thousands of institutional documents, committee minutes, sermons, membership records, and photographs that capture a unique slice of American history.

While Riverside’s collections have long been used by local, national, and international researchers, today the church itself is exploring these materials to analyze the trajectory of its stance on issues of racial justice.

Members and staff have drawn on the archives as the basis for a seven-week online lecture series, “Remember and Repair: Expanding Racial Justice and Equity in Church and Society,” and for social justice writing workshops.

The interdenominational church has also examined the archives to track the makeup of its own membership, noting that until the 1950s or ‘60s, it was almost exclusively white and wealthy.

“Our past is integral to our identity,” says Diane Russo, the archives’ director. “We’re looking at our journey – all the good and the bad – to assess who we are as a congregation. We want to see how we’ve dealt with things. It’s important for us to do this work to help figure out where we’re going in the future.”

‘You can’t heal what you don’t reveal’: Archives as a path to justice

No one would argue that a Bible printed in 1493, stained-glass windows from the 16th century, and Heinrich Hofmann’s 1890 masterpiece “Christ in Gethsemane” aren’t valuable assets. But just as valuable to The Riverside Church, established as an interdenominational church in 1930, are its thousands of institutional documents, committee minutes, sermons, program booklets, membership records, audio and video recordings, and photographs that capture the development of liberal Christianity and a unique slice of American history.

It’s a history seen through the eyes of a New York City church grappling in real time with the changes happening in society. With documents from predecessor churches dating back to 1841, Riverside’s collections have long been used by local, national, and international researchers, historians, and journalists as primary sources. Today, the church itself is making greater use of its archival materials to analyze the trajectory of its stance on issues of racial justice.

“Our past is integral to our identity,” says Diane Russo, who came to Riverside four years ago as director of its archives. “We’re looking at our journey – all the good and the bad – to assess who we are as a congregation. We want to see how we’ve dealt with things. It’s important for us to do this work to help figure out where we’re going in the future.”

“You can’t heal what you don’t reveal,” is a chant echoed by Martha Wiggins, a congregant who has been accessing the archives to create educational programming. Earlier this year, she and a planning team used materials from the archives to design a seven-week online lecture series, “Remember and Repair: Expanding Racial Justice and Equity in Church and Society.” A focus of the series was to help congregants and friends look at the church’s racial history with a sharp, critical lens.

“The archives helped us take a more factual than anecdotal approach to history,” Ms. Wiggins says. “Many people think of an archive as housing a lifeless past, but it breathes, ... it speaks to us of our beginnings and our unfinished work. It houses stories that are begging to be excavated and shared.”

“Materials to interrogate our history”

One way Riverside’s stories are being told is through its social justice writing workshops and their ensuing publications. The workshops were launched during the pandemic, which laid bare many of the inequities in health care and social services that severely affected marginalized communities. For Riverside’s fourth workshop, the planners collaborated with Ms. Russo to identify photographs, media, and works of art that could be used to spark creativity and prompt the writing process.

“We wanted to give people who have been drawn to justice work a creative way to communicate who has inspired them,” says longtime Riverside member Luvon Roberson, who designed the online workshops with her team. “In turn, these writers will inspire others to see writing as part of the justice journey.”

Rarely seen photos of Nelson Mandela, Maya Angelou, Coretta Scott King, Betty Shabazz, and church members at a protest rally were starting points for writing about social justice.

“The archives gave us evidence, ... materials to interrogate our history,” says Ms. Roberson. “We need to know about efforts that championed the good and the right. History has shown us that there can be downturns where injustice and oppression become overwhelmingly present. During that time, it’s important to counter injustice with truth.”

Riverside’s early leaders were considered more progressive on theological issues of the day, as well as on issues of social and racial justice. Yet the archives show little change in the church’s racial makeup during its first three decades, which is consistent with most churches of that era.

“We’ve found maybe one African American in the choir and an instance of a couple of African Americans who came to our worship services,” Ms. Russo says of photos from the 1940s and ‘50s. “We didn’t have diversity in terms of economic class either; the church was on the wealthier side.”

The philanthropist and oil magnate John D. Rockefeller Jr. was a primary benefactor when the current edifice was erected in the late 1920s.

Things started to change in the 1950s and ‘60s. One indicator is the number of photos and recordings of racially diverse individuals who have spoken from the church’s pulpit. From 1961 to 1967, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at the church six times and delivered from its chancel his “Beyond Vietnam” address, which decried that war on moral and economic grounds. Over the years, the church has recorded and kept photographs of speakers such as Nelson Mandela, Marian Wright Edelman, Jesse Jackson, Desmond Tutu, Fidel Castro, Maya Angelou, the Dalai Lama, and Cesar Chavez.

A call for reparations

One lesser known but perhaps equally impactful pulpit orator was civil rights activist James Forman. On May 4, 1969, he interrupted the Sunday morning service to make a series of demands for white congregations to pay reparations to African Americans. “Because the church was recording the service, we have this event on tape as well as news clippings – and the church’s response,” says Ms. Russo. “This collection is incredibly important because it had repercussions and it’s relevant to today’s world.”

“Riverside’s journey toward justice is not a straight line; it zigs and zags,” adds Carol Fouke-Mpoyo, who worked with Ms. Russo and others to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Mr. Forman’s “Black Manifesto,” reflecting on its significance then and now. “We didn’t want to present a myth about being a perfect social justice voice; we wanted to look at the complexity of our history. We needed to look at where we failed and where we succeeded. What we’re trying to do is use the materials in our archives to inform ... the truthful telling of our own history.”

Combing through its archives is also challenging the church to examine its iconography, including pieces that have significant historical and financial value. Looking through decades of committee minutes and other reports has uncovered the context in which visual images were chosen. “Why were certain images used?” questions Ms. Fouke-Mpoyo. “What do we make of art that doesn’t reflect our current diversity? ... Are any images seriously problematic? These kinds of questions can be teaching moments. ... They are part of the process, helping us determine who we want to be.”

Central to The Riverside Church’s process of discovery and identity is harvesting more of the history stored in its archives. To aid that effort, Ms. Russo and the archives’ three-member staff launched a digitized platform this year that showcases its fine art collections, sculptures, photographs, newsletters, sermons, media, and other materials. The new site allows easier access to anyone wanting to dive into the church’s collections.

“The archives are meant to inspire people to uncover the past and be transparent,” Ms. Russo wrote later in an email. “There can be many historical perspectives, but we aim to be as objective as possible. Examining history can often be challenging and leave us with many questions. Our aim is to talk about it, reflect on it, and allow it to inspire a way forward.”

Difference-maker

With after-school center, trans activist Sumi Das seeks kinder future

In eastern India, an after-school center run by trans women is helping kids reconnect with learning. It is also forging compassion and solidarity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Anmol Arora Contributor

Since 2020, transgender rights activist Sumi Das has been running a unique learning center – known locally as the Gurukul – from the ground floor of her West Bengal home. Students are hand-picked based on family need, and receive free tutoring, meals, and extracurricular classes such as dance and yoga.

In a country where public schools struggle with overcrowding and low resources, after-school programs like the Gurukul can fill gaps in education and help children engage with school, say policy experts. And for the center’s trans volunteers and staff, working with children can be a much-needed reprieve from the stigma they experience in mainstream society.

Ms. Das also sees the learning center as a tool to foster mutual compassion between trans people and other vulnerable communities in her area.

In India and elsewhere, bullying and harassment leads many young trans people to drop out. With about half the workers at the Gurukul being trans, Ms. Das hopes students will remember how their caretakers made them feel loved and respected – and that they’ll treat their trans peers the same.

“When we just work within the community for ourselves, that won’t lead to any change,” she says. “If we work with and for the whole society, the actual change will come.”

With after-school center, trans activist Sumi Das seeks kinder future

Arbina Khatun makes about $3 a day working at a small convenience store with her husband in the West Bengal village of Ghughumari.

She knows her 6-year-old son, Shyan Mia, could benefit from a private tutor, but at $12 to $25 a month, the family could never afford it. “I do not have any income apart from what we earn from the shop,” she says. “We use that to feed ourselves.”

So instead she sends him to a nearby learning center founded by transgender rights activist Sumi Das and referred to as the Gurukul.

Ms. Das founded the center in 2020 when schools closed during COVID-19 lockdowns. Shyan is one of 24 children from underprivileged families who come to this unique facility for meals, tutoring, and extracurricular activities. Ms. Khatun says the center also gave her son warm sweaters and socks during winter.

After-school programs like the Gurukul can fill gaps in public education and help children better engage with school, education policy experts say. For the center’s trans volunteers and staff, working with children can be a much-needed reprieve from the stigma they experience in mainstream society.

Ms. Das hopes the learning center can foster mutual compassion between trans people and other vulnerable communities in her area.

“When we just work within the community for ourselves, that won’t lead to any change. If we work with and for the whole society, the actual change will come,” she says.

Building the Gurukul

Ms. Das has lived and worked in this region of eastern India for over a decade. She left home at age 14 and moved to a nearby railroad junction. “At that time, I started doing sex work for just 15 rupees [less than $1] to get food to eat,” says Ms. Das.

Gradually, she got involved with the local hijra community – one of many trans, intersex, and gender-diverse communities with distinct family structures and customs in India – and with HIV/AIDS and human rights activism.

In 2009, she founded the Moitrisanjog Society, a rural collective of trans and gender-nonconforming people who support each other and advocate for employment and health care access. The Gurukul became an offshoot of this effort, and was designed as a way to branch out and build solidarity with other marginalized groups during the pandemic.

“We wondered what work we can do with and for the ‘mainstream’ community,” says Ms. Das. “That is how we came up with this center.”

Some parents were reluctant to send their kids to the facility, which is set up on the first floor of Ms. Das’ residence, saying, “If my child studies at a hijra household, they will also become a hijra,” recalls Ms. Das. But others saw value.

The current students have been hand-picked based on family need. Several are children of migrant and daily wage workers, and another has a mother dealing with mental health challenges. Despite hardships, these parents had a safe place to send their kids during lockdowns.

Now that public schools have reopened, the Gurukul has shifted to after-school programming. Children arrive by 3 p.m. for additional lessons in core subjects such as Bengali, math, and science, as well as training in dance, yoga, and art. At 7 p.m., they have dinner before returning home.

In a country where public schools struggle with overcrowding and fail to offer much in the way of extracurricular enrichment, it’s a level of education that can be tough to come by.

Educational intervention

India promises free and compulsory elementary education, but in many areas, schools fall short of government standards. For instance, the Right to Education Act mandates a ratio of 1 teacher to 30 students in lower primary classes, yet the teacher-pupil ratio in government-aided schools in West Bengal is 1-to-73.

“The kids do not get the same attention in school,” says Shamima Hasan, who has a master’s degree in English and is one of three teachers offering daily academic tutoring at the Gurukul. “They are able to focus on their studies here.”

Sudipta Bagchi, a dance instructor who volunteers at the learning center at least twice a month, agrees that it offers families unique opportunities.

“The kids in the village here are strangers to many things. So they have that excitement [for the class],” says Ms. Bagchi, adding that the children are always enthusiastic and cooperative during dance lessons, despite her classes being somewhat sporadic.

Parul Sharma, education specialist at UNICEF Jharkhand, says that nongovernmental organization-run education initiatives such as the Moitrisanjog Gurukul can help supplement the government’s efforts for universal and high-quality education, especially after COVID-19 interruptions.

These programs’ importance “is getting amplified as many children need to be reconnected with learning and need additional psychosocial support,” she says.

But Ms. Sharma adds that after-school programs are only stopgap measures, and what happens during the six to eight hours of classroom time is more critical to children’s development. The best outcome, she says, would be to integrate these initiatives into the larger education system and adopt some of their best practices, in part because the mainstream school system can reach a much larger population.

The program’s reach is a concern for Ms. Das and her team as well. They want to expand the facility but face funding issues. Current donations don’t cover the $220 per month needed to pay for program essentials, including meals and teacher honorariums, but Ms. Das is committed to keeping the initiative afloat.

To her, it’s not just about giving vulnerable children a fighting chance, but also about introducing the next generation of youth to trans people and planting seeds of compassion.

Envisioning a kinder future

In India and elsewhere, young trans people report significant levels of bullying and harassment in school, leading many to drop out. With about half the workers at the Gurukul being trans, Ms. Das hopes students will remember how their caretakers made them feel loved and respected – and that they’ll treat their trans peers the same.

In the meantime, the center also serves as a sort of haven for Ms. Das and other trans people involved in the project.

“I feel lonely day and night,” says Iswar Chanda, who helps with the facility’s administration. “Everyone says I am a man, and I don’t have the right to motherhood. But I know I can be a mother.”

Between errands, Ms. Chanda takes every opportunity to shower students with love. She says even brief moments of connection help satisfy that maternal instinct.

Subho Das (no relation to Sumi Das) also loves caring for the children. Working as the Gurukul’s cook provides the teenager a reprieve from her home environment, where she faces hostility due to her gender identity, particularly from her elder brother.

“He rebukes me for dressing and being the way I am,” she says. “I don’t know what to do. My sense of self is not the same as that of men; it is like that of a woman. I can’t do anything about it.”

The kids, on the other hand, affirm her identity. They compliment her dancing when she drops in on dance classes. She playfully admonishes them when they run around during dinnertime, but once they settle down, they’re always appreciative of her cooking.

“I wake up in the morning, [and] I wait for them to come,” says Subho Das. “I keep on thinking about how I can spend time with them.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Europe’s weapon against Russian disinformation

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

One of Ukraine’s strengths against Russia has been truth-telling – about Moscow’s real intent and covert actions, whether in cyberspace or in combat zones. Last week, the country was equally forthcoming in helping Moldova, its weaker neighbor with whom it shares a 759-mile border. President Volodymyr Zelenskyy warned that Russia had a specific plan “to break the democracy of Moldova.”

The next day, a Russian missile did indeed fly over Moldovan airspace. Also, Moldova’s prime minister, Natalia Gavrilița, resigned, citing “so many crises caused by Russian aggression in Ukraine.” Moldovan President Maia Sandu quickly nominated her former defense adviser, Dorin Recean, as prime minister while praising the outgoing one. Mr. Zelenskyy’s intelligence alert may have temporarily thwarted a Russian plot to control Europe’s poorest country.

In recent years, Moldova has made progress in providing accurate information to counter the false narratives spread in Moldova by Russia. The European Union, NATO, and the United States have helped beef up Moldova’s cybersecurity and the country’s campaign against disinformation.

For Moldova, a bit of truth-telling by Ukraine may have saved the day.

Europe’s weapon against Russian disinformation

One of Ukraine’s strengths against Russia has been truth-telling – about Moscow’s real intent and covert actions, whether in cyberspace or combat zones. Last week, the country was equally forthcoming in helping Moldova, its weaker neighbor with whom it shares a 759-mile border. President Volodymyr Zelenskyy warned that Russia had a specific plan “to break the democracy of Moldova and establish control over Moldova.”

The next day, a Russian missile did indeed fly over Moldovan airspace. Also, Moldova’s prime minister, Natalia Gavrilița, and her government resigned, citing “so many crises caused by Russian aggression in Ukraine,” such as high energy prices, inflation, and an influx of refugees.

Yet Mr. Zelenskyy’s intelligence alert may have temporarily thwarted a Russian plot to control Europe’s poorest country. Moldovan President Maia Sandu quickly nominated her former defense adviser, Dorin Recean, as prime minister while praising the outgoing one. “We have stability, peace and development, where others wanted war and bankruptcy,” said the president, who has led the effort for Moldova to join the European Union.

In recent years, Moldova has made progress in providing accurate information to counter the false narratives spread in Moldova by Russia and pro-Russia oligarchs and politicians in the former Soviet state. The EU, NATO, and the United States have helped beef up Moldova’s cybersecurity and the country’s campaign against disinformation. Pro-Russia television stations have been curtailed. Pro-Russia protests last fall to oust the government failed. And this winter, Moldova has found alternative energy sources in response to Russia’s curbs on gas exports.

“Moscow’s campaign against the Sandu government is a prime example of hybrid warfare,” Iulian Groza of the Institute for European Policies and Reforms told Der Spiegel. “Instead of tanks, the Russians are using energy and disinformation.”

In much of Europe, Russia has used lies in an attempt to destabilize democracies, especially in the Baltic states. France has helped lead the EU effort against Russian disinformation.

“We must be driven by the desire to defend and promote access to good-quality information for the greatest number,” said Catherine Colonna, France’s minister for Europe and foreign affairs.

“The first requirement is truth,” she said in a speech last month. “Dialogue is possible only if it relies on a shared vision of truth, realities, and facts. But as we’re all aware, our ability to bring out this shared vision is currently the target of concerted attacks.” In Moldova’s case, a bit of truth-telling by Ukraine may have saved the day.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Will I see you again?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Melissa Hayden

When a loved one is lost, we can turn to God – who cares for each of us, eternally – for inspiration that comforts, heals grief, and replaces unsettling questions with peace of mind.

Will I see you again?

That question, “Will I see you again?” frequently came to thought for several months after my husband passed on. The question was both tantalizing and unsettling.

I was deeply comforted by the weekly Bible Lessons found in the Christian Science Quarterly, which constantly fed me with ideas that encouraged me to feel God’s ever-present care. Still, I felt a sometimes-not-so-subtle curiosity about whether my path and my husband’s would cross again after my own passing.

Christ Jesus’ resurrection proved his message of eternal life, and his followers continued to share that message after Jesus’ ascension. The Apostle Paul declared, “The gift of God is eternal life through Jesus Christ our Lord” (Romans 6:23).

A question and answer from “Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, begins, “After the change called death takes place, do we meet those gone before? – or does life continue in thought only as in a dream?” The answer states, in part, “When we shall have passed the ordeal called death, or destroyed this last enemy, and shall have come upon the same plane of conscious existence with those gone before, then we shall be able to communicate with and to recognize them” (p. 42).

I realized I was wondering whether my husband and I could perhaps continue where we’d left off. And I yearned to see my husband healthy and happy again. Interestingly, I also discovered that I secretly hoped he would have outgrown some annoying habits as well. Then our future life together would be perfect!

Considering these wistful imaginings, I recognized the subtle suggestion that some part of good had died at the same time my husband passed, or maybe had even been missing while he was still alive. But Christian Science teaches that good never ends, never diminishes, and is never fragmented, because good is God, and God is eternal. There is no separation of man – which includes all of us as God’s, Spirit’s, beloved children, made in His image – from God, or man from man, since all of creation is spiritual and included in one seamless whole.

So the good in our life is never filtered through a mortal or taken away through mortality’s inevitable ending. Deity’s unchanging nature and provision are consistent and fully present at all times.

Not long after I gained these insights, the curiosity ceased, along with any last vestiges of grief. I understood more thoroughly that we have, here and now and in infinite ways and means, all that we could ever need – God’s care for us is always providing the spiritual ideas and inspiration needed. We don’t for one moment have to guess whether we will find completeness at some future time. We could never be less than complete as God’s spiritual likeness.

I also realized that I was content with all the wonderful husbanding that my dear heavenly Father was providing me every moment. Since that time, I’ve seen innumerable instances of divine Love’s tender care in the exact moment it was needed. I am confident in Love’s same tender care for my husband. It’s been five years since my husband’s passing, and I can honestly say that any wistfulness or grief is long gone.

Spiritual growth is an essential aspect of God’s loving purpose for us, and it is experienced most naturally when we are obedient to the divine Principle of good, which is God. It may be tempting to feel that good needs to come at some future time. But divine goodness is actually available now in multifarious and ongoing ways. We are never separated from good. And the same is true of those who have passed. We don’t reunite as mortals in some future life. We are all united spiritually, for all time, in the Life that is eternal.

Every moment of our existence is governed by God, cared for by divine Love; every need is met by Spirit. It always has been, and never will be otherwise.

Adapted from an article published in the May 6, 2019, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

From one heart to another

A look ahead

Come back tomorrow, when we will have a story on the resilience of children following the earthquake in Syria and Turkey.