- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Chicago mayoral race spotlights cities’ post-pandemic struggles

- Short on food and funds, working-class Pakistanis rely on resilience

- China’s Ukraine dilemma: Broker peace or boost Putin?

- Sobfests, pop songs: TikTok upends France’s literary landscape

- Growing winter food – and community spirit – in a geothermal greenhouse

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Filling some holes left by newspaper closures: More online newsrooms

Ali Martin

Ali Martin

Chances are, you read your news on a digital device: a smartphone, tablet, or computer. You’re definitely reading this electronically. The Monitor’s daily print edition shifted entirely online in 2009 – the first nationally circulated newspaper to do so.

Fourteen years later, the digital transformation of news is in full effect. The number of online newsrooms across the United States hovers around 550, according to a 2022 report by Northwestern University. More than 60 were started in the three years before the report.

“This is a crossroads. No question,” says Margot Susca, an assistant professor of journalism, accountability, and democracy at American University in Washington.

But the expansion of digital doesn’t come close to replacing the loss of local newspapers. The Northwestern report averages closures at more than two a week; at least 2,500 newspapers have shuttered since 2005. Yet despite the rise in so-called news deserts – communities with limited or no access to local coverage – Dr. Susca is optimistic.

“What’s born from that crisis is innovation, opportunity, and a huge amount of work that’s being done across the country by foundations, scholars, and entrepreneurs that is very exciting right now,” she says.

Ken Doctor, a veteran journalist and news industry analyst, is one of those entrepreneurs. He started Lookout Santa Cruz, which recently marked two years in operation. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Mr. Doctor said he’s hopeful the startup will be profitable this year. So far, the traditional combination of subscriber fees and advertising has been bolstered by a significant amount of nonprofit seed funding.

“We know our model works, given sufficient time and money – the secret for all good start-ups,” he says in an email to the Monitor, referring to Lookout’s viability. “What’s most important going forward is community-based knowledge and relationships.”

Dr. Susca also puts community engagement at the heart of journalism’s new age. “We can’t have long-term a new system ... that is based on wealthy people,” she says, noting the investment model that she credits for the loss of local papers.

“What are community members willing to pay for?” she says. “That’s the key question moving ahead.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Chicago mayoral race spotlights cities’ post-pandemic struggles

Lori Lightfoot is the first pandemic-era mayor attempting to run for reelection in a major city. The campaign is a window into how Chicago has – and has not – rebounded from the COVID-19 crisis, with problems like crime now top of mind.

Less than one year after Lori Lightfoot triumphantly took office as Chicago’s first Black female mayor and one of America’s most prominent LGBTQ leaders, COVID-19 brought life in her city to a screeching halt.

Ms. Lightfoot, like other mayors across the country, found herself managing mask mandates, school closures, and vaccine distribution, along with surging crime and mass protests against racism and police brutality.

Now, with an unfavorability rating that’s more than double her favorability, she’s trying to persuade her constituents to give her another term. Tuesday’s vote may serve as an indicator of how well cities like hers are rebounding from the public health crisis. More broadly, the election is spotlighting a city grappling with a sense of urban decline, as Chicago, like many major cities, confronts partially empty downtowns and issues of public safety, policing, and race.

“When you ... upend [people’s] lives, as we had to do during the course of the pandemic, that causes a lot of anxiety. And I think there’s still an undercurrent of that,” Ms. Lightfoot says in an interview with the Monitor. “It’s absolutely informing people’s perceptions of, ‘Is the city going in the right direction or not?’”

Chicago mayoral race spotlights cities’ post-pandemic struggles

At campaign events across Chicago’s South and West sides, Democratic Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s supporters all drive home the same point: Don’t judge her on the past four years. Think, instead, about what she could do in the next four.

“You can’t change nothing in four years,” says local Alderman Emma Mitts to a cheering crowd in West Garfield Park, an area with the city’s highest homicide rate. “In a pandemic? Even being a sister?”

It’s an atypical message for an incumbent politician – but then, nothing was typical about Mayor Lightfoot’s first term. Less than one year after the former president of the Police Board triumphantly took office as Chicago’s first Black female mayor and becoming one of America’s most prominent LGBTQ leaders, COVID-19 brought life in her city to a screeching halt.

Ms. Lightfoot, like other mayors across the country, was on the pandemic’s front lines. She found herself managing mask mandates, school closures, and vaccine distribution, along with surging crime and mass protests against racism and police brutality. She engaged in high-profile fights with fellow Democrats in Springfield and powerful left-leaning unions, while also being attacked in conservative media.

Politically, almost no big-city mayor made it through those years unscathed. Former Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti’s approval rating dropped nearly 20 percentage points, while New York Mayor Bill de Blasio left office with a lower favorability rating among New Yorkers than former President Donald Trump. Term-limited Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney made news last summer when, after a July Fourth shooting, he said he’ll “be happy” when he’s not in charge anymore.

Ms. Lightfoot, with an unfavorability rating that’s more than double her favorability, is one of the few who’s trying to persuade her constituents to give her another term. As such, Tuesday’s vote may serve as an indicator of how well cities like hers are rebounding from the public health crisis – and whether politicians weighted down by that tumultuous time can have a second act. More broadly, the election is spotlighting a city grappling with a sense of urban decline, as Chicago, like many major cities, confronts partially empty downtowns and issues of public safety, policing, and race.

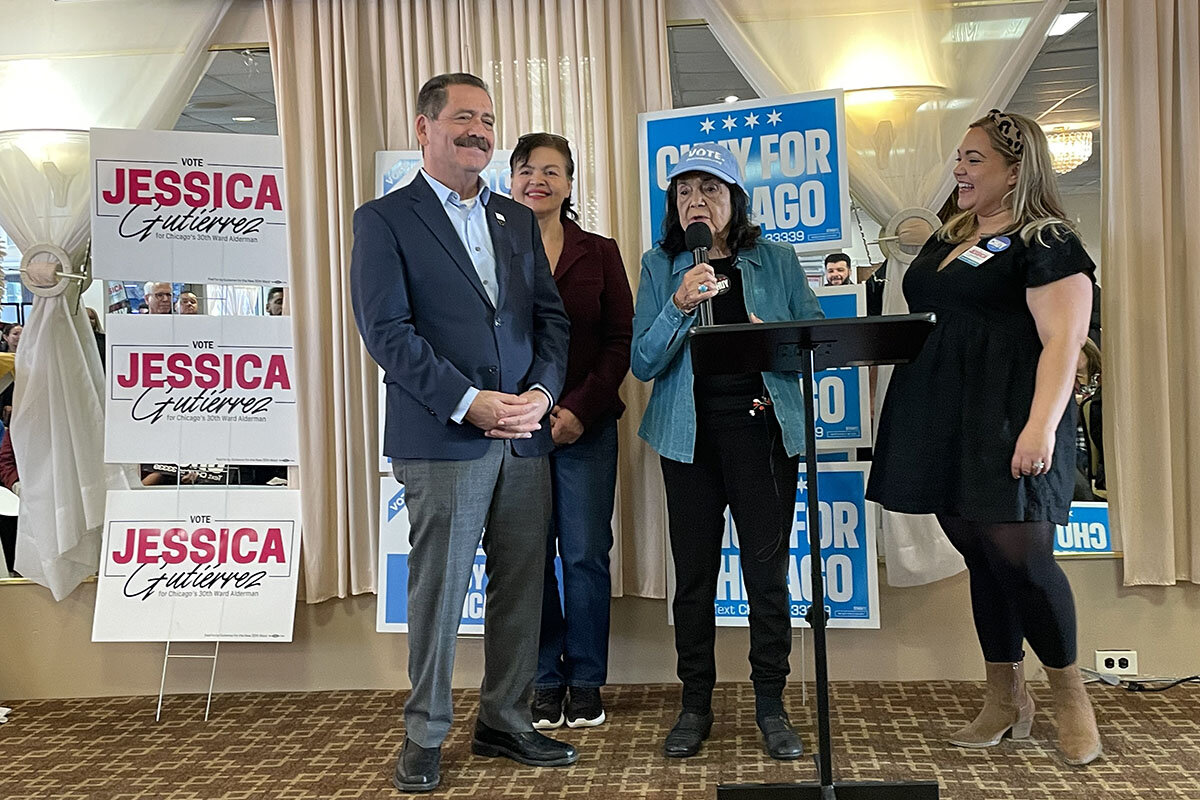

With nine candidates running – all of them Democrats – polls suggest the race is largely between four: Ms. Lightfoot; U.S. Rep. Jesús “Chuy” García, who represents part of the city; Paul Vallas, who served as Chicago’s budget director and CEO of Chicago Public Schools in the early 1990s; and Brandon Johnson, a Cook County commissioner and former teacher. Some analysts are bearish on Ms. Lightfoot’s chances of even making it to an April runoff election between the top two vote-getters if no candidate wins an outright majority.

“Of course, we made mistakes along the way,” Ms. Lightfoot says in an interview with the Monitor following the West Side event. “But we learned from those mistakes, and I think that’s made me a better leader.”

“When you take the certainty of people’s lives, and you upend those lives as we had to do during the course of the pandemic, that causes a lot of anxiety. And I think there’s still an undercurrent of that in the city,” says the mayor. “It’s absolutely informing people’s perceptions of, ‘Is the city going in the right direction or not?’”

Crime and public safety

To that question, almost three-fourths of Chicago voters answered no in a recent poll. While the health crisis itself has receded and life has gone back to normal in many ways, specific problems that flowed from the pandemic remain front and center.

Public transportation ridership rates are still far below what they were pre-pandemic, with many residents complaining of delays, dirty trains, and an unsafe environment. Enrollment in Chicago’s public schools, which saw three teacher strikes in the space of three school years, continues to fall.

At campaign events across the city, voters repeatedly cited public safety as their top concern. With homicides hitting a 25-year high in 2021 and carjackings and thefts up across the city, more citizens are now worried about crime than about criminal justice reform, the economy, education, immigration, and taxes – combined. Several companies have closed shops or offices in Chicago, citing crime as a driving factor.

“It’s a new level of desperation and hopelessness that, I think, is playing a big factor in the rise of crime,” says Representative García, one of Ms. Lightfoot’s opponents, in an interview. “It’s impacting all of our lives.”

Like other U.S. cities, Chicago saw mass protests over police brutality following the murder of George Floyd by police officers in Minneapolis in May 2020. Some of those protests turned violent, leading Ms. Lightfoot to impose a citywide curfew and ask the governor to call in the Illinois National Guard.

Still, critics say Ms. Lightfoot was too slow to act, enabling looting and damage to dozens of businesses. “When she let them riot a second time on Michigan Ave., I was done,” says Bill, a Chicago voter who declined to give his last name.

Just like the Democratic Party as a whole, Chicago’s mayoral candidates offer a range of policy solutions to address the crime problem. The fact that not one of them is talking about “defunding the police” speaks to how much voters’ priorities have changed over the past few years.

Mr. Johnson is emphasizing the need to fund more youth employment opportunities and mental health services. Ms. Lightfoot, Mr. García, and Mr. Vallas are all promising to hire more police officers and ensure that the department is fully funded.

Mr. Vallas, in particular, is running as a “pro-police” candidate.

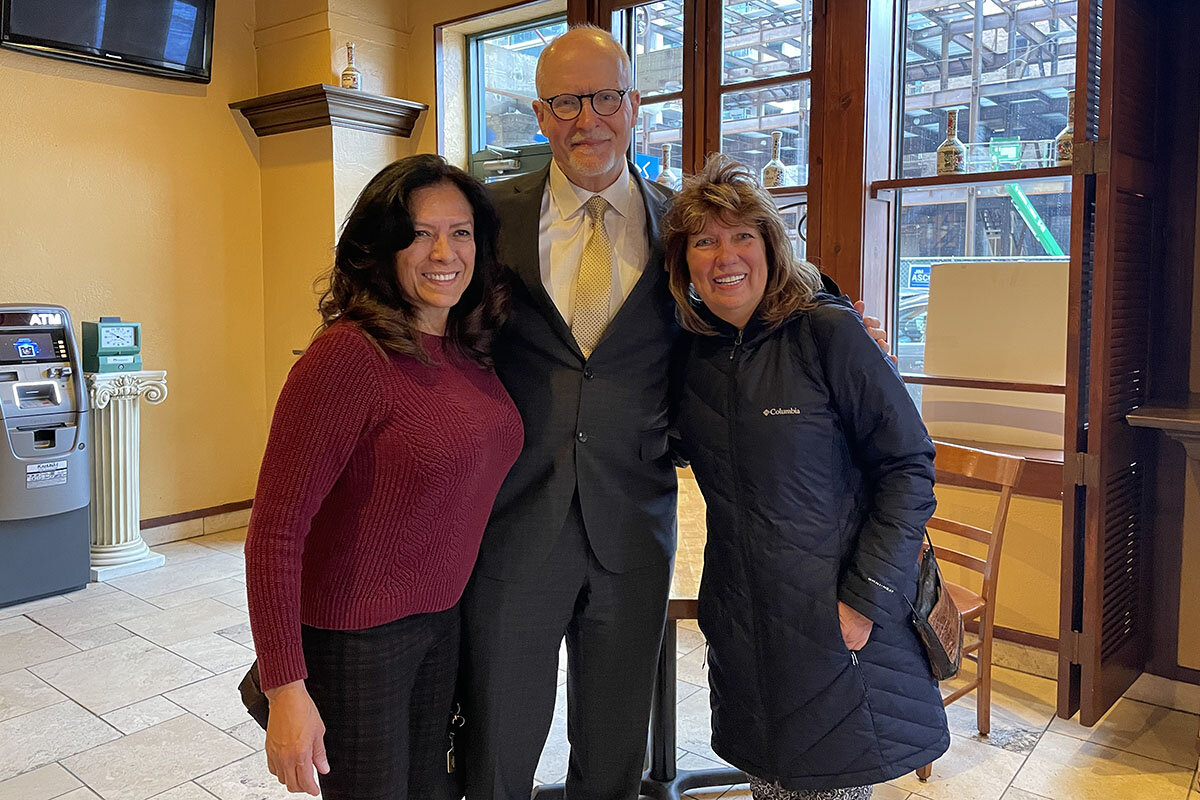

“After the George Floyd riots, [Ms. Lightfoot] literally destroys proactive policing. Suddenly the police are being restrained,” says Mr. Vallas, in an interview at a Greek restaurant that one voter characterizes as a “cop bar.”

“Public safety is the number one, two, and three problems,” Mr. Vallas continues, periodically pausing the conversation to shake hands with a voter or pose for a photo. “Lori Lightfoot inherited a lot of problems ... but I think that bad decisions made things worse.”

Fights with unions

Several voters here agree that Ms. Lightfoot was dealt a “bad hand,” but then made it worse.

“It showed the quality of her leadership,” says Jennifer Frei, a consultant attending a Vallas campaign event at a bar in Logan Square with her husband, Gerald Wilk, a retired carpenter. The two haven’t decided which candidate to vote for, but they aren’t eager for a second Lightfoot term.

“She just won’t be able to get anything done,” says Ms. Frei, referring to Ms. Lightfoot’s lack of allies in the city.

Since taking office, the mayor and former prosecutor has found herself at odds with Illinois’ Democratic Gov. J.B. Pritzker as well as fellow Democrats in the City Council. She’s had high-profile disputes with the Fraternal Order of Police, which has endorsed Mr. Vallas, as well as the Chicago Teachers Union, which has endorsed Mr. Johnson.

Both unions sparred with Ms. Lightfoot over COVID-19-related issues, with the FOP opposing a vaccine mandate and the CTU striking in 2021 and 2022 for more COVID-19 protections. The relationship between Ms. Lightfoot and the city’s teachers has been particularly acrimonious, with the mayor accusing the teachers of holding the city’s children “hostage” with their work stoppages and the leader of the teachers union saying Ms. Lightfoot was on “a one-woman kamikaze mission to destroy our public schools.”

Some say the disputes had less to do with the pandemic and more to do with Ms. Lightfoot’s aggressive personal style.

“I’m not so sure how much [the pandemic] had to do with her troubles,” says John Mark Hansen, a political scientist at the University of Chicago. “She’s had a very, very difficult time with the City Council. She’s had a couple of floor leaders quit on her – and that never happens. People who were strong allies of her, who said, ‘I’ve had enough.’”

Supporters contend that Ms. Lightfoot, as a Black, openly gay woman, faces a double standard. Chicago, after all, has a long tradition of brash mayors – including Richard J. Daley, who ran the city for two decades and was dubbed “the last of the big city bosses,” and Rahm Emanuel, the famously foul-mouthed former chief of staff to President Barack Obama, who had his own conflicts with the teachers union.

“When [Mr. Emanuel] cursed out CTU, no one said anything,” says Monica Faith Stewart as she leaves a campaign event for Ms. Lightfoot on Chicago’s South Side. “They just expect women to eat tea and crumpets.”

Real People, Real Voices

How does a political reporter go about gathering vox pop that’s meaningful – authentic personal perspectives that contribute value to stories, and don’t just parrot pre-cooked talking points? Story Hinckley speaks with host Clay Collins about the persistence, balance, and respect that the work requires.

Michael Mayden, walking out with half a dozen “Lori Lightfoot for Chicago” yard signs tucked under his arm, nods his head in agreement.

“The pandemic hasn’t changed the role of the mayor, but it made the media stereotype her,” says Mr. Mayden. “They’re biased against a Black woman leading this city.”

But Mr. Johnson, in an interview at a pastry shop in Wicker Park, says it’s too late to repair the damage.

“If the mayor had one challenge, people might have mercy on her,” says Mr. Johnson. But “she’s had multiple tussles. I don’t know if there is anyone that she gets along with.”

Racial politics

In the final weeks of the race, Ms. Lightfoot has focused many of her attacks on Mr. Johnson, who has picked up millions of dollars in donations from the teachers union and others. In a city that is both highly diverse and highly segregated, Ms. Lightfoot has leaned into identity politics, bluntly telling Black constituents that a vote for Mr. Johnson, who is also Black, would likely only serve to elevate a non-Black candidate.

“Any vote coming out of the South Side for somebody not named Lightfoot is a vote for Chuy García or Paul Vallas,” said Ms. Lightfoot at a recent event. She added that Black voters who didn’t support her should “stay home” and not vote, a comment she later walked back.

Critics accuse Ms. Lightfoot of being racially divisive. In 2021, she made waves when she announced that she would only grant interviews to reporters of color, describing the Chicago press corps as “overwhelmingly white” – a stance that drew a lawsuit from a conservative group.

But racial politics are shaping other campaigns as well. Waiting for Mr. García to speak at an event in Belmont Cragin, an almost 80% Hispanic neighborhood, Maria Reyes, a preschool director who lives in the area, says she’s supporting Mr. García because “as Latinos, we want to support him.”

Ms. Reyes adds that she would like to see “equal opportunities for everyone – not just the South Side.” The comment is a reference to Ms. Lightfoot’s Invest South/West development initiative, which brought at least $2.2 billion to the city’s historically Black neighborhoods.

Ms. Lightfoot repeatedly highlights that initiative in her campaign stops in these two areas, where Ms. Mitts and other supporters encourage Black voters “to show up like never before.”

As dozens of supporters filter out of the hall, the campaign blasts Lizzo’s “About Damn Time” over a speaker – a song the chart-topping star wrote to “celebrate our survival, and celebrate how far we’ve come” over the past few years.

Reflecting back on her crisis-inflected term, Ms. Lightfoot tells the Monitor that the pandemic made long-standing challenges from health care to housing to food insecurity suddenly “acute and urgent” – which, in a way, was a needed catalyst for change. And while “we haven’t solved every problem by a long shot,” she argues Chicago made real strides “coming together, not only as a city government, but with our partners in the community.”

“There’s a lot of lessons learned that I’m probably frankly going to be unpacking for the rest of my life,” she says.

Short on food and funds, working-class Pakistanis rely on resilience

Amid Pakistan’s escalating financial crisis, a visit to a working-class neighborhood in Lahore reveals daily struggles and deep wells of resilience.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Pakistan’s import-dependent economy was already reeling from the sharp increase in oil prices caused by the war in Ukraine when monsoon floods destroyed millions of acres of farmland last year. Now, with the nation low on food and unable to pay its hefty import bill, working-class Pakistanis must summon every ounce of resilience to feed their families.

As inflation hits a 48-year-high, the price of wheat flour, the most basic of staples in Pakistan, has nearly tripled to around 150 rupees ($0.57) per kilogram. Vendors in Ghulam Mohammad Bhatti Colony, a working-class neighborhood in the center of Lahore, are going door to door buying stale rotis so they can break them down into cheaper flour to sell on the market. Other residents are relying on their community and picking up odd jobs.

For some, even the possibility of Pakistan defaulting – a certainty, experts say, if the country can’t secure emergency aid from the International Monetary Fund – isn’t enough to shake their resolve.

“The thing is, when I came into this world I had nothing and when I leave it, I’ll have nothing,” says resident Javed Ahmed Khan, who sells mosquito control equipment. “If you can control your desires, you can get by with just about anything.”

Short on food and funds, working-class Pakistanis rely on resilience

In the center of Lahore – the city affectionately known as the beating heart of Pakistan – lies a working-class neighborhood called the Ghulam Mohammad Bhatti Colony. It is built across what once was a narrow streamlet with water so clean that the community used it to wash their clothes and bathe children.

“It was beautiful,” says resident Ahsan Bhatti. “There were trees on either side of the water and every evening people used to gather around and sit in the shade.”

Things began to change in the 1990s, when gated communities and industrial parks were constructed nearby and their sewage systems started flowing into the water. Today, Ghulam Mohammad Bhatti Colony finds itself encircled by three of the city’s most exclusive neighborhoods – Model Town, the Defence Housing Authority, and the Pak-Arab Housing Scheme – but children here walk barefoot through rundown streets, avoiding the garbage-strewn trench, once a flowing stream, and scavenging food from other rubbish.

Income inequality is nothing new in Pakistan, yet it’s being thrown into a harsher spotlight as a severe cost-of-living crisis forces working-class Pakistanis to summon every ounce of resilience. Inflation has reached a 48-year-high with consumer prices up 27.6% compared to the same time last year, and the price of wheat flour, the most basic of staples in Pakistan, has nearly tripled to around 150 rupees ($0.57) per kilogram. Some in Ghulam Mohammad Bhatti Colony are going door to door buying stale rotis so they can break them down into cheaper flour to sell on the market. Others are relying on their community and picking up odd jobs to feed their families.

“You see that mound of gravel there?” says primary school teacher Khurram Javed, pointing in the distance. “After I’m done speaking to you, I’ll go over there and offer to get rid of it at a price. That’s what it’s come down to. Last night, the only way I was able to eat was by cleaning a gutter.”

Mounting crises

Pakistan’s import-dependent economy has suffered a number of external shocks over a short period. The monsoon floods, which destroyed millions of acres of farmland and disrupted agricultural supply chains, came when the economy was already reeling from the sharp increase in oil prices caused by the war in Ukraine. This further exacerbated the country’s chronic balance of payments problem, with the result that Pakistan did not have enough foreign currency in its reserves to pay its hefty import bill.

“Because we didn’t have any dollars coming in, food items that were being imported from abroad would get stuck at our ports,” explains economics and finance commentator Shahbaz Rana, based in Islamabad. “When suppliers within Pakistan saw that there was a commodity shortage in the market, they started hoarding these food items and caused an escalation in price.”

Talks with the International Monetary Fund ended on Feb. 9 without a deal, though officials say they were given a road map for reforms needed to unlock the $1.1 billion in emergency aid. Meanwhile, food and medicine shortages – which come as Pakistan’s security situation deteriorates and power outages wrack cities – have many working-class people pointing fingers at their rulers.

“It’s the army and the government that are robbing this country,” says local barber Mohammad Rizwan. “They’re the ones who have multiple cars worth tens of millions of rupees.”

A United Nations report published in 2021 estimated that perks given to the elite amounted to approximately $17.4 billion.

“What I earn here isn’t enough to feed my family,” Mr. Rizwan adds. “Every month I’m falling further and further in debt, and it’s a good thing that the house I live in belongs to the family or I’m sure I would be out on the street.”

So acute is the crisis affecting the neighborhood that parents are taking children out of schools and putting them to work. Muhammad Afzal Raza, the principal of the local high school, says that many residents cannot even provide their children with pens and paper. “Most parents really do want to send their children to school, but the fact is they simply can’t afford it,” he says.

In spite of these difficulties, however, members of the community refuse to be despondent.

Faith and community

Emmanuel Sardar, one of the community’s Christian residents, says that his faith in God stops him from worrying about the future. “We believe that Allah is the one who is responsible for sustaining us and that he knows best how much to give us.”

Faith is likewise a source of strength for Hina Ansari. “What are our hardships compared to the ones faced by our Prophet in the early days of Islam?” says the mother of five who has lived in the neighborhood for more than 10 years. “Why should we complain about poverty? No! We have to work and get ahead.”

Ms. Ansari supplements her husband’s monthly salary of 20,000 rupees by stitching clothes in their apartment and working as an agent for the local marriage bureau. It was initially a struggle to convince her husband to allow her to work.

“People think that if a woman goes out to work, she’ll meet all sorts of other women who won’t have the right sort of character,” she explains. “But I told him that everything I’d do, I’d do for my children and that I’d never do anything to compromise his honor.”

There is even a sense that financial distress has brought the community closer. “I owe about three months’ rent,” admits resident Emmanuel Masih. “But my landlords are understanding. I believe that when you’re good to people and keep good relations with people, they are also willing to help you out. And whenever we get money, we drop all our other expenses to pay off what we owe in rent.”

For some, even the possibility of Pakistan defaulting – a certainty, experts say, if the country can’t secure the IMF bailout – isn’t enough to shake their resolve.

“The thing is, when I came into this world I had nothing and when I leave it, I’ll have nothing,” says Javed Ahmed Khan, who sells mosquito control equipment. “If you can control your desires, you can get by with just about anything.”

Patterns

China’s Ukraine dilemma: Broker peace or boost Putin?

Chinese leader Xi Jinping faces a dilemma whose resolution will define his country's role in the world: to seek a peacemaking role in the Ukraine war, or provide his ally Vladimir Putin with weapons.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Ned Temko

As Chinese leader Xi Jinping returns to the world stage, now that the pandemic is over, he faces a dilemma. What to do about the war in Ukraine? The approach he takes will impact more than the conflict itself. It could alter the direction of world politics once it is over.

Mr. Xi is due to deliver a “peace speech” on Friday, one year to the day after Russia’s tanks, armor, and troops poured across the border into Ukraine.

But the Chinese leader faces a fundamental choice, underscored this week when U.S. officials revealed intelligence reports that he is considering providing arms and munitions to Vladimir Putin.

Will Beijing seek to position itself as the key player in an eventual negotiated settlement? Or will it become Russia’s indispensable military ally in trying to turn the tide of the war?

Messrs. Xi and Putin share a common interest in constraining Washington’s power and influence.

But if Mr. Xi – reportedly planning a trip to Moscow – offers weaponry to Mr. Putin, that would cross a “red line” in Europe’s relationship with China, the top European Union diplomat said last week. And Europe is China’s biggest market.

Mr. Xi’s challenge will be to balance his country’s political interests with its economic ones.

China’s Ukraine dilemma: Broker peace or boost Putin?

On the first anniversary this week of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, attention has been focused on dueling speeches by two leaders deeply invested in its outcome, Russian President Vladimir Putin and U.S. President Joe Biden.

But the emergence of a third voice could turn out to matter even more – that of China, Mr. Putin’s main ally and the United States’ true superpower rival.

After 12 months spent largely on the sidelines, Chinese leader Xi Jinping has in recent days begun to signal his intention to take a more active role. He is reportedly planning a visit to Moscow in the coming months.

How Mr. Xi chooses to approach the war in Ukraine will impact more than the conflict itself. It could alter the direction of world politics once it is over.

On the diplomatic front, Mr. Xi is due to deliver a “peace speech” on Friday, one year to the day after Russia’s tanks, armor, and troops poured across the border into Ukraine.

But the Chinese leader faces a fundamental choice, underscored this week when U.S. officials revealed intelligence reports that he is considering providing arms and munitions to Mr. Putin.

Will Beijing seek to position itself as the key player in an eventual negotiated settlement? Or will it become Russia’s indispensable military ally in trying to turn the tide of the war?

The prism through which Mr. Xi will make that call is clear: his own nation’s interests, and in particular his core vision of a rising 21st-century China displacing the U.S. and its allies from their post-World War II position of dominance.

But it is an especially difficult choice because of the seismic changes in world politics caused by Mr. Putin’s so-far unsuccessful campaign to take over Ukraine.

Those changes, alongside pandemic pressures at home, explain Mr. Xi’s uncharacteristic political hibernation over the past year, offering occasional rhetorical succor to his beleaguered ally but otherwise choosing to stay out of the fray.

When Mr. Xi’s top foreign policy representative, Wang Yi, visited Europe last week, the envoy was left in no doubt about the geopolitical fallout from the war.

Mr. Xi has long assigned Europe a central role in his project to expand his nation’s global clout. The 27-nation European Union is Beijing’s largest trade partner and, with the U.S., has been key to China’s rise.

Until February last year, Mr. Xi envisaged European countries inexorably asserting more autonomy from Washington, potentially helping to insulate China from a worsening of its own U.S. ties.

But the war has revived a trans-Atlantic sense of common values and common cause.

Foreign Minister Wang arrived at the annual Munich Security Conference calling for a return to economic business as usual with Europe, and urging Europeans to distance themselves from what he suggested was self-interested U.S. hawkishness on Ukraine. He was met with a collective cold shoulder and a stern warning not to ship arms to Russia.

In a meeting with the Chinese envoy, Josep Borrell, the EU’s chief diplomat, said that providing military support to Mr. Putin would be “a red line in our relationship.”

Mr. Xi now faces the task of defining his country’s relationship with Russia.

Twelve months ago, that must have seemed straightforward. In a 5,000-word joint statement during Mr. Putin’s visit to China for the Beijing Winter Olympics, the two leaders pledged a friendship “without limits” and mapped out a shared vision of a world order in which America was just one major country among others.

They criticized what they portrayed as a pretentious Western notion of “democracy” that trampled on other countries’ sovereignty, and denounced American “military blocs” as a threat to other nations’ security.

But since the war broke out, and as it turned against the Russians, Mr. Xi and other Chinese officials have rarely gone beyond echoing the overall Kremlin narrative, implying that NATO’s expansion plans made the invasion an act of Russian self-defense.

Mr. Xi’s conundrum now is that he still values the political underpinning of his relationship with Russia: the two sprawling neighbors share a common interest in constraining Washington’s power and influence. Mr. Wang, who visited Moscow after his European mission, unequivocally reaffirmed the alliance, portraying it as rock-solid.

Yet the Chinese leader also knows that providing Mr. Putin with weaponry would likely be fatal to prospects of reversing the downward spiral in relations with Washington and cause a major rift with European countries as well. Beijing would likely face added Western sanctions and find itself painfully isolated from its major markets.

Mr. Xi has been weighing his options for months, doubtless hoping he could avoid making a clear decision so heavily laden with consequences.

That’s where the “peace speech” comes in. It is very unlikely to find much traction in the short run, especially with Russia now poised to mount its largest military operation in Ukraine since the invasion.

But it is a signal that finding a way to end the war that Mr. Putin began is not only in Ukraine’s interest, or that of America and its allies.

It’s in China’s as well.

Sobfests, pop songs: TikTok upends France’s literary landscape

France’s publishing industry is staunchly conservative, but now young influencers on TikTok are using the hashtag #BookTok to create a newfound enthusiasm for reading – and challenging the way literature is consumed.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Colette Davidson Special correspondent

In France, where literary critique gets its own national radio program and publishing houses are staunchly traditional, one popular platform is turning the country’s literary landscape on its head.

With its viral #BookTok hashtag, TikTok has swept the publishing world here, changing the way French literature, especially novels for young adults, is sold and consumed. BookTokeurs post videos of themselves sobbing as they recount recent reads, gleefully unboxing book purchases, offering three-minute literary critiques, and using voice-overs and the latest pop songs to narrate their thoughts on the latest release.

The #BookTok hashtag took off in the United States in 2020, with emotive videos created by a handful of young women. Since then, TikTok’s influence on publishing has exploded. Amazon has a TikTok Book Club, and Barnes & Noble stores across the U.S. dedicate a section to #BookTok recommendations.

In France, some publishers remain skeptical of #BookTok’s value, questioning whether it’s only about pumping up book sales and promoting lowbrow books.

But those who get on board are seeing their sales rise exponentially. And through their contagious passion, the mostly young, female #BookTok influencers are generating a newfound enthusiasm for reading.

Sobfests, pop songs: TikTok upends France’s literary landscape

In her recent TikTok video, 19-year-old Victoire Ducluzeaud sobs in rapid-fire snapshots, as she recounts her recent reading experiences. In one clip, black mascara streaks down her cheeks as she waves a thick paperback in front of the camera, crying, “Why?!” In another, she can barely get the words out between tears, “How could he have done such a thing?”

The video sobfest has received nearly 75,000 views, and readers can’t get enough. In this particular clip, comments range from, “Give us your top five books that make you cry!” to “Now I feel less alone.”

Ms. Ducluzeaud’s videos, which she has posted multiple times per day since 2021, are part of the latest phenomenon to hit France’s publishing world: #BookTok.

What began in the United States has now crossed the ocean to change the way French literature – especially novels for young adults – is being consumed. In addition to crying, BookTokeurs post videos of themselves gleefully unboxing book purchases, offering three-minute literary critiques, and using voice-overs and the latest pop songs to narrate their thoughts on recent reads.

While some publishers here are skeptical of #BookTok’s value, those who get on board are seeing their sales rise exponentially. In France, where literary critique gets its own national radio program and publishing houses are staunchly traditional, the popular platform is slowly turning the country’s literary landscape on its head. And through their contagious passion, the mostly young, female #BookTok influencers are generating a newfound enthusiasm for reading.

“BookTokeurs are being taken seriously now,” says Camille Cardoso, a community manager for three French publishing houses’ social media accounts. “Publishers are starting to see that they have an impact, that their opinion counts. ... Their videos shatter the distance. ... We feel their emotions,” she says. “Most publishers who work with young adult literature now know that partnering with influencers is absolutely essential to sell books.”

“A strong and fast evolution”

The #BookTok hashtag took off in the U.S. in 2020, with emotive videos created by a handful of young women, including Cait Jacobs of @caitsbooks and Ayman Chaudhary of @aymansbooks. In one clip, Ms. Chaudhary wails comically, holding her copy of Madeline Miller’s “The Song of Achilles,” before throwing it against the wall. The same novel was included in a list of “Books that will make you sob,” posted by Selene Velez on @moongirlreads_, and the viral videos caused a spike in the book’s sales nine years after it was first published. Since then, TikTok’s influence on publishing has exploded. Amazon has a TikTok Book Club, and Barnes & Noble stores across the U.S. dedicate a section to #BookTok recommendations.

In France, it’s nearly impossible to calculate the number of new TikTok book lovers, with accounts popping up daily. But in September, 376,000 of the 13 billion TikTok videos associated with the #BookTok category worldwide came from French users. And those in the literary industry here are taking notice of the platform’s success.

“We are constantly trying to adapt and evolve with the trends,” says Agnès Fradet, a digital project manager for youth literature at the Editis publishing house. “TikTok has had such a strong and fast evolution. We see someone crying for a few seconds in a video and then a book sells 3 million copies. We’ve had to adapt.”

Editis, like most publishing houses for young adult literature, now has its own TikTok account alongside its Instagram and Facebook presence. The publisher regularly sends copies of books to influencers – either through unpaid or paid partnerships – to increase publicity and sales. Often, the decision of which books to translate into French is based on what does well on TikTok.

Publishers are only one part of the puzzle, however, and booksellers like the Presqu’île bookstore in Strasbourg now offers a #BookTok search function on its website. The annual Book Fair of Youth Literature in Montreuil has its own TikTok account.

Authors are using the platform as a place of exchange. Joël Dicker – winner of France’s Prix Goncourt in teen literature in 2012 – opened a TikTok account in October, telling users, “I really think we need to be on all channels that allow people to read and be read.”

Those efforts are slowly translating into sales. According to the Centre National du Livre (National Book Center), 18% of French people ages 7 to 25 choose books based on having heard about them on social media such as Instagram and TikTok.

French publisher Hachette Romans recently saw its first TikTok bestseller with its translated version of Tillie Cole’s “A Thousand Boy Kisses.” Even though it came out in 2016, the book sold 9,000 copies in the last six months after it was featured on social media.

Publishers credit these types of success stories not to Instagram – which functions based on photos and well-crafted stories – but to TikTok and its specific ability to break down barriers.

“With Instagram, it’s very aesthetic and thought out, but TikTok is much more immediate,” says Ms. Fradet of Editis. “We see the person’s emotions right away; there’s no filter. It’s much more accessible than a classic literary critique one might read.”

Questioning BookTok’s impact

Still, some question the seriousness of the #BookTok phenomenon – whether it’s more about pumping up book sales or if it’s truly affecting how French people, particularly youths, read.

“I do wonder if BookTok is having the most impact on young people who already read regularly, or if it’s actually pushing those who don’t read at all to read more,” says Sylvie Vassallo, the director of the Youth Book Fair in Montreuil. “In the end, there’s nothing harmful about it. Anything that helps people read more is a positive thing.”

BookTok has also been criticized as promoting “lowbrow” literature, since more #BookTok influencers post about young adult fiction in the fantasy or romance genres than the classics, like Proust or Voltaire.

While many of the videos are less than 30 seconds long and focus on one aspect of a book – like how the user felt reading a racy scene, or what it’s like to spend the whole day immersed in a book – others are more serious critiques. And that has created questions about what literary criticism, a sacred beast in France, means today.

“[BookTok] isn’t literary critique. It’s about selling books,” says Arnaud Viviant, a literary critic for La Masque et la Plume, a national public radio program on France Inter that has existed since 1955. “Pretty soon, quality readers will be like whales: an endangered species. And we need good readers to have good writers.”

But that isn’t necessarily the opinion of those doing it. Pauline Locufier, who at 19 years old has 45,000 followers on her account @lectrice_a_plein_temps, has considered becoming a critic one day – even if she understands that her TikTok posts are more book summaries than true critiques.

“Some people tell me, ‘You should be reading the classics,’ but young adult fiction is what I prefer,” says Ms. Locufier. “I’m always reading literary reviews and observing critics. I want to learn the right vocabulary and have their presence. They are the reference in the industry.”

Ms. Ducluzeaud says she posts to TikTok for the pure love of books and sharing. She has always enjoyed reading, and posting to her 174,000-odd followers via her @nous_les_lecteurs account has allowed her to go even further. In 2021, she read 149 books and in 2022, she read 219.

Since she started posting about her reading adventures online, she has made friends with people across France and the world.

“So many people have written me saying, ‘I had stopped reading but thanks to you, I started again,” says Ms. Ducluzeaud. “I just want to share my passion.”

Difference-maker

Growing winter food – and community spirit – in a geothermal greenhouse

A child’s question prompted this urban farm to seek a greenhouse for winter growing – and for strengthening a community.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

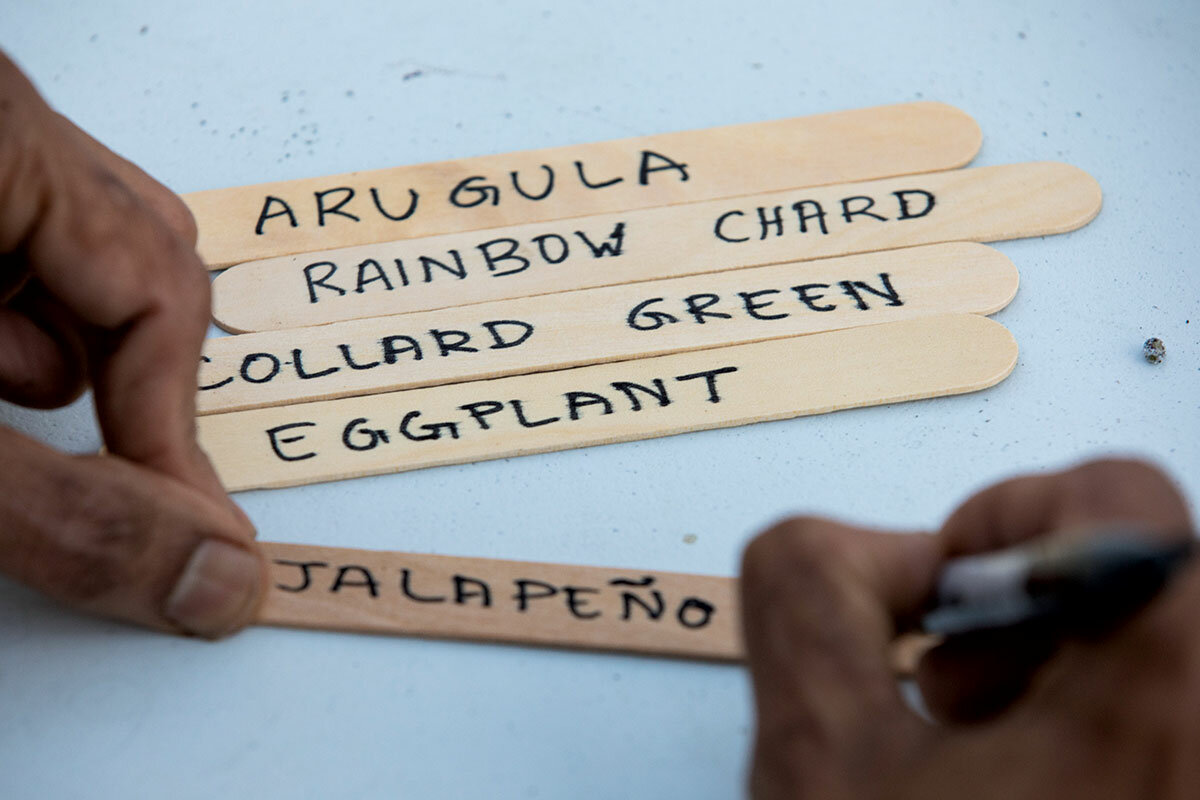

Tucked near a highway underpass, a greenhouse glows faintly in the cold night. Inside, volunteers stand in the warmth, crowded around two pizzas topped with homegrown basil. Rows of potted greens, herbs, peppers, eggplants, and even strawberries line shelves along the walls.

The greenhouse is a new project of Eastie Farm, an educational urban farm in East Boston. Focused on feasible climate action, the nonprofit – and its new greenhouse – provides the surrounding community with greater control over its food supply.

The geothermal greenhouse operates as a heat exchange, circulating a fluid below the frost line to gather warmth. Inspiration for the greenhouse sparked during one of Eastie Farm’s nature classes taught to local students: Kids wanted an opportunity to get outside and farm in the colder months.

The farm gives residents agency in a community that faces both high rates of food insecurity and climate-related risks of coastal flooding.

“Eastie Farm is a great example of innovative urban agriculture,” says Shani Fletcher, director of GrowBoston, Boston’s Office of Urban Agriculture. “I think we need to try everything we can ... to both make our city climate-resilient and to mitigate climate change.”

Growing winter food – and community spirit – in a geothermal greenhouse

Tucked near a highway underpass, a greenhouse glows faintly in the cold night. Inside, volunteers stand in the warmth, crowded around two pizzas topped with homegrown basil. Rows of potted greens, herbs, peppers, eggplants, and even strawberries line shelves along the walls.

The greenhouse is a new project of Eastie Farm, a nonprofit educational urban farm founded in 2016 and housed in East Boston. Focused on feasible climate action, the nonprofit – and its new greenhouse – provides the surrounding community with greater control over its food supply. The building runs on geothermal energy and is the first of its kind in New England. As a model of what 21st-century development could look like, the greenhouse represents a practical application of geothermal, an often inaccessible technology.

“Everything that we do, we try to make sure that it has a relevance here and now, and it serves the purpose for the people who are living here today,” says Kannan Thiruvengadam, the director of Eastie Farm. “This technology is already possible. You don’t have to wait for tomorrow or the day after.”

The geothermal greenhouse operates as a heat exchange. Below the frost line, Earth’s temperature stays at a steady 50 to 60 degrees Fahrenheit year round. A fluid composed of water and antifreeze is pumped up from the ground, runs through a compressor, passes over a warm coil, and finally blows into the greenhouse as warm air. The fluid then heads back underground, forming a closed loop system.

Warmth in the winter

By drawing the temperature below the frost line up and into the greenhouse, the system warms in the winter and cools in the summer. Add in some warmth from sunshine, and winter temps in the greenhouse can be as high as 70 degrees.

Inspiration for the greenhouse sparked during one of Eastie Farm’s nature classes taught to local students: Kids wanted an opportunity to get outside and farm in the colder months. “They even asked, ‘Come on, there must be something we can grow in the wintertime,’” Mr. Thiruvengadam remembers. “I said, ‘Grow ice!’”

There was no one to guide Eastie Farm through the project – because it hadn’t been done before. Greenhouses are typically powered by propane and aren’t all that green, despite their name. They leak warm air in the winter and are often abandoned or used as storage in the hot summer months.

Funding entities and contractors alike were unsure how to help. Information was crowdsourced. On Oct. 13 – at 9:37 in the morning – the greenhouse began to fill with warm air, without any help from fossil fuels.

Greenhouse manager Will Hardesty-Dyck aims to use the 1,500-square-foot enclosure to grow year-round, for about 2,000 pounds of produce yearly.

Inside the greenhouse, string lights crisscross the ceiling underneath an insulation layer that is pulled tight to trap the daylight’s long-gone heat inside the building. The smell of soil fills the space with the feeling of spring.

“I just really love growing plants,” Mr. Hardesty-Dyck says. “That makes me tick – and then being able to do that in this sort of organization where we’re really engaging with people and addressing needs.”

The neighborhood Eastie Farm serves is as unique as its greenhouse. East Boston is a community that suffers a disproportionate burden of climate hazards. The peninsula is home to Boston Logan International Airport, houses stores of petroleum-derived products, and is at risk of climate-related flooding. It also experiences a high level of food insecurity.

Mr. Hardesty-Dyck is already fielding requests to house budding saplings as well as to cultivate culturally relevant foods that may not be available – at least not fresh – at supermarkets. South and Central American community members have asked for tropical and subtropical fruits, such as mamoncillo. There have also been requests for herbs such as cilantro and mint, a common ingredient in Moroccan tea.

Communal purpose

Eastie Farm aims to ensure that there is no stigma for immigrant and other community members in accessing good food – an effort rooted in the idea that economic insecurity is at the heart of food insecurity. By partnering with local farms that share their values, Eastie Farm provides a community-supported agriculture (CSA) program with three levels: paid, subsidized, and free.

“The reality is that we don’t have a lot of access to fresh fruits and vegetables. So the farm really is a great way to expose yourself to a variety that you don’t easily get in the stores that we have,” says Bessie King, a CSA subscriber and East Boston resident.

Eastie Farm challenges the conventional definition of an urban farm.

“Urban farms have more to harvest from their proximity to a lot of consumers and from their connections with rural farms than just by maximizing what [they grow] in every square inch,” Mr. Thiruvengadam says.

Shani Fletcher, director of GrowBoston, Boston’s Office of Urban Agriculture, agrees. “Eastie Farm is a great example of innovative urban agriculture,” she says. “I think we need to try everything we can ... to both make our city climate-resilient and to mitigate climate change.”

One of the pillars of the nonprofit is education. Students can learn about the greenhouse effect and its meaning for the planet while standing in a greenhouse and experiencing it hands-on. The farm also manages four school gardens, which give students “ownership or buy-in to the school community,” says Sam Pichette, a fifth grade teacher at Bradley Elementary whose students have participated in nature classes here. “It helped to strengthen ties between the students and to the community they live in.”

Eastie Farm gives residents agency in a community that faces overdevelopment and gentrification, says Ms. King. “A place like Eastie Farm is a beacon of hope because it’s run by community members; it’s run by volunteers; it’s run by fellow farms that are all local.”

At the end of the night, everyone lines up to take home small bags of assorted greens. “Party favors!” says a smiling volunteer in a bright pink coat. It is the beginning of many expected greenhouse crops.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Binding a nation’s wounds with forgiveness

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In a democracy, can forgiveness help mend political divides? The answer might be found in Kyrgyzstan, a Central Asian country of some 7 million people, with more than 100 ethnic groups and a history of overthrowing elected leaders.

Last Saturday, the president, Sadyr Japarov, quietly brought together five former presidents in neutral territory, the United Arab Emirates, for a meeting “with the aim of strengthening national unity,” as he put it. Each of the five did not know ahead of time that they would be meeting.

By most accounts, the conclave went well. Mr. Japarov called on the Kyrgyz people to be “forgiving and set aside the hard feelings and complaints of the past.” His main focus was to have enough harmony among these top politicians to convince a diverse people not to fall for the politics of division.

His gesture of political accord still needs to play out. The nation must find a balance between legal justice and forgiveness. Yet with plenty of problems for this former Soviet state, Mr. Japarov offered this: “If we want to strengthen our sovereignty, independence and develop Kyrgyzstan, let’s put aside the past, our grievances and our complaints.”

Binding a nation’s wounds with forgiveness

In a democracy, can forgiveness help mend political divides? The answer might be found in Kyrgyzstan, a Central Asian country of some 7 million people, with more than 100 ethnic groups and a history of overthrowing elected leaders.

Last Saturday, the current president, Sadyr Japarov, quietly brought together five former presidents in neutral territory, the United Arab Emirates, for a four-hour secret meeting “with the aim of strengthening national unity,” as he put it. Each of the five did not know ahead of time that they would be meeting.

By most accounts, the conclave went well. “For a long time, I have been harboring the idea that we can perhaps join forces and become one nation if we bring together all our presidents, who were initially elected by people and then came to a sad end,” Mr. Japarov wrote on his Facebook page.

He called on the Kyrgyz people to be “forgiving and set aside the hard feelings and complaints of the past.” One former president, Kurmanbek Bakiev, lives in Moscow after being found guilty in absentia over the killing of civilians during an uprising that ousted him in 2010. Another, Almazbek Atambayev, was only released from prison on Feb. 14.

A third, Askar Akayev, also lives in Moscow after being overthrown in the 2005 Tulip Revolution. A fourth, Sooronbai Jeenbekov, was forced to leave office in 2020. The country’s only female president, Roza Otunbayeva, served on an interim basis.

Mr. Japarov, who promised similar meetings of “reconciliation and accord,” said that he alone could not allow Mr. Bakiev, who faces a long prison sentence, back into the country. “The relatives of those who were killed should forgive at first,” he said. “If he comes, he will be taken into custody. We must abide by the decision of the court,” he said, citing a need for rule of law.

His main focus was to have enough harmony among these top politicians to convince the diverse population of Kyrgyzstan not to fall for the politics of division.

“My only thought was for the supporters of each president, for the inhabitants of the seven regions [of Kyrgyzstan] to concentrate [their energies] in one direction, to leave politics to one side, to think about the development of the nation, of the economy,” he said, according to his press secretary.

His grand and perhaps only symbolic gesture of political accord still needs to play out. The nation still needs to find a balance between legal justice and the healing effects of forgiveness. Yet with plenty of problems for this former Soviet state, Mr. Japarov offered this: “If we want to strengthen our sovereignty, independence and develop Kyrgyzstan, let’s put aside the past, our grievances and our complaints.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Can the world be saved?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Trinka Wasik

Turning to a spiritual view of life helps us more tangibly experience the healing, saving power of Christ.

Can the world be saved?

I traveled to Israel recently and took a tour with a lovely woman who showed me Bethlehem and Jerusalem. We talked a lot about Jesus and what he did for the world. She asked me, “Do you believe he was the Messiah?” I told her I did. She said, “I don’t. The Messiah was supposed to save the world, and the world hasn’t been saved.”

I understood what this woman was saying. So much of humanity continues to cry out for salvation. But, I wondered, does the world need to be “saved”?

The Bible says, “He spake, and it was done; he commanded, and it stood fast” (Psalms 33:9). To believe in an all-powerful, all-good creator refutes any suggestion that people could possibly improve upon what was made. The creation God made, as stated in the first chapter of Genesis, is good. Period.

So what needs to be saved? It’s humanity’s view of the world that needs to be redeemed. Jesus, as the Messiah, demonstrated the ability to see the world from the point of view of God, Spirit, and witness its spiritual perfection. Mary Baker Eddy says of Jesus in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “He did life’s work aright not only in justice to himself, but in mercy to mortals, – to show them how to do theirs, but not to do it for them nor to relieve them of a single responsibility” (p. 18).

In this way, we must work out our own salvation, as the Bible says. This means gaining a new sense of divine Love’s reality through Jesus’ teachings and example – the true view of our relationship to God and to our fellow man. Salvation is the demonstration of our harmonious, all-blessing at-one-ment with God and all the good that God creates.

The healings Jesus’ accomplished were individual. When he healed a blind man, he didn’t at once heal all the blind people throughout the world. Considering this has been helpful with my desire to relieve suffering in the world. I have found that as I align my thinking with the allness and goodness of God and cherish everyone’s salvation, not only do I find peace, but the situation at hand also improves, often in unexpected ways.

In the early 1990s, my husband and I were diagnosed as infertile, and we decided to adopt a child from Russia. While we were in the country, the Russian government closed adoptions to Americans, and we went home childless after meeting the children in need. It was heart-wrenching.

Back home, an acquaintance told us of a woman whose husband had recently left her and who felt her only option was to look for adoptive families for some of her children. We decided one of her little boys was perfect for us, and wholeheartedly agreed to take him in, but there were several other families the mother was considering. As desperation began to again settle in, I prayed.

I prayed to know that God knew what was best for this child and was caring for him. The answer came clearly to me: “This child can never be separated from his true Father.” I knew that God would meet all his needs perfectly.

And then I thought of those children in Russia, and I knew that this message of the universality of God’s love also applied to them. I next thought of children throughout the world who seemed to be lacking. I finally saw that I, too, am God’s beloved child. Nobody could ever be separated from our divine Parent, God. The Christ-spirit is present with all of us to align our thoughts with God’s perfection in ways exactly suited to each individual.

Three days later I learned that the boy’s father had decided to keep him. I felt I had caught a glimpse of the universal truth about God’s relationship to His children, and that was followed by an unmistakable individual proof of that truth. It wasn’t very long after this that I joyfully discovered that I was pregnant.

It is up to each of us to strive to see the allness and goodness of God. Christ, Truth, does save. And in striving for our own salvation, we can’t help but include our trust in God’s salvation for all.

Adapted from an article published in the Feb. 13, 2023, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

‘Little Cone’ grows stronger

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when Scott Peterson, reporting from Ukraine, looks at how one year of war has unified the people, generating stories of courage and resilience.