- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Ten years after bombing, Boston runs on

Noelle Swan

Noelle Swan

Few things say spring has sprung in Boston like Marathon Monday.

This year, the annual Boston Marathon on April 17 carries added significance as the city marks 10 years since two young men detonated makeshift bombs near the finish line on April 15, 2013. The explosions killed three people and seemingly ripped a hole in the social fabric of the city.

Monitor illustrator Karen Norris was running her first marathon that day and was abruptly stopped from completing the race. The turmoil that surrounded the bombings left Karen, like many Bostonians, “in a dark place.”

At the same time, she was buoyed by the support she found, particularly from fellow runners. And before long she committed to trying again the following year.

“We can’t live in fear,” she says. “You fall off your bike, you get back on it.”

So in 2014 she plodded across the state once more and achieved the belated triumph of crossing the finish line. Along the way she was reminded of what had drawn her to the marathon in the first place: “I felt like I was a part of something much bigger than myself.”

A decade later, memories of the day still weigh heavily, and yet, “There’s been so much progress and healing and camaraderie,” she says. “I feel like we gained a new perspective – on ourselves personally and as a city.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Dominion v. Fox: What could it mean for press freedoms?

The truth is the North Star of journalism, and the Supreme Court has carved out broad protections to allow reporters to do their work. A defamation trial brought against Fox News could have wide-ranging ramifications.

This week is set to bring a major test of modern freedom of the press in an era of disinformation.

Fox News argues that it was simply airing newsworthy allegations when it repeated conspiracy theories about the 2020 presidential election. The defamation case brought by Dominion Voting Systems represents a “profound threat to the First Amendment,” Fox’s lawyers argue. If Fox loses, they say, it would be a disaster for freedom of the press.

In one respect, the outcome is not in doubt: A judge has already ruled that conspiracy theories about Dominion and its voting machines constitute defamation per se. But a high legal bar still remains: The company must prove that Fox acted with actual malice.

The $1.6 billion defamation suit, originally set to begin Monday, has been delayed while the parties consider whether to settle.

There is a lot more than money at stake. The case revisits the widespread conspiracy theories about election fraud, and the extent to which disinformation is threatening the country’s democratic institutions.

Some free speech advocates are concerned a jury ruling against Fox could have a chilling effect on journalism. But others maintain that giving its audience what it wanted, even at the expense of the truth, should render Fox News legally vulnerable.

Dominion v. Fox: What could it mean for press freedoms?

This week is set to bring a major test of modern freedom of the press in an era of disinformation.

The case of Dominion Voting Systems v. Fox News has its roots in conspiracy theories aired about voting machines after Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election.

Fox News argues that it was simply airing newsworthy allegations when it repeated those falsehoods. The defamation case brought by Dominion represents a “profound threat to the First Amendment,” Fox’s lawyers argued in a filing. If it loses, the network argues, it would be a journalistic disaster, opening networks and newspapers to all kinds of lawsuits.

In one respect, the outcome is not in doubt: A Delaware judge has already ruled that conspiracy theories about Dominion and its voting machines aired by Fox News are false and constitute defamation per se.

“The statements at issue were dramatically different than the truth,” said Superior Court Judge Eric Davis in a ruling. “In fact, although it cannot be attributed directly to Fox’s statements, it is noteworthy that some Americans still believe the election was rigged.”

But a high legal bar still remains: The company must prove that Fox acted with actual malice.

The $1.6 billion defamation suit, originally set to begin today, has been delayed reportedly while the parties consider whether to settle.

There is a lot more than $1.6 billion in damages at stake. For one thing, the Dominion case revisits the widespread conspiracy theories about election fraud, and the extent to which these lies and the broader problems of disinformation are threatening the country’s democratic institutions.

Some free speech advocates are concerned a jury ruling against Fox could indeed have a chilling effect on journalists’ constitutional duty to inform the public. But others maintain that giving its audience what it wanted, even at the expense of the truth, should render Fox News legally vulnerable.

“From my perspective, I think Dominion should win this case, because I do think this is a clear case of actual malice,” says Genelle Belmas, professor of journalism at the University of Kansas. “I think the judge laid it out with help from Dominion pretty clearly in this case. But in the larger sense, that doesn’t fix the problem of disinformation, and it could be weaponized, potentially weaponized, against press freedoms.”

“And if Fox wins, then, of course, that can be weaponized, too,” she continues, citing recent discussions about the case in which a Fox victory could be framed as vindicating the lies about the 2020 election.

The Dominion case comes at a moment when some thinkers and government officials – especially conservatives – are starting to question the extent of the news media’s special free speech protections.

New York Times v. Sullivan

For nearly 60 years, the nation’s legal traditions have more or less shielded news outlets from costly defamation lawsuits brought by anyone deemed a “public figure,” even when the information is false and damages that figure’s reputation.

As a technical legal term, “actual malice” has long set a sky-high bar for any public figure to sue a news organization for defamation. Coined in the seminal 1964 Supreme Court case New York Times v. Sullivan, the term was defined as publishing any defamatory information with “knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.” The Supreme Court has also defined actual malice as publishing a “calculated falsehood.”

“Times v. Sullivan does set a high bar,” says Professor Belmas. “When I talk to my students about it, I always give them the famous quote from Justice [William] Brennan’s majority decision, about the First Amendment being ‘a profound national commitment’ to a principle of free speech: ‘debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open.’”

The case was not about the Times’ journalism, but about an advertisement placed by an Alabama civil rights organization, soliciting donations for Martin Luther King Jr.’s legal defense. The ad described clashes between protesters and police, and contained factual inaccuracies. A local official successfully sued the newspaper for libel under Alabama law.

The Supreme Court overturned the Alabama court’s decision 9-0, and used what was a minor case to proclaim this larger principle about the meaning of free speech and freedom of the press. Just the specter of defamation could cause a “chilling effect” on public debate, so in this case a unanimous Supreme Court set a significant legal barrier for public officials trying to sue news organizations.

In subsequent decisions, the Supreme Court expanded the scope of the actual malice standard to include “public figures,” as well as “limited public figures” who are thrust into the “vortex” of public debate.

“There’s a line in Sullivan that I really love that basically says, quoting from another case, ‘Whatever is added to the field of libel is taken from the field of free debate,’” says Andrew Geronimo, director of the First Amendment Clinic at Case Western Reserve University School of Law in Cleveland.

“But the idea of actual malice is that the news media should be able to talk freely about public figures, and most particularly in Times v. Sullivan, our government officials, and we should be able to get some things wrong,” he continues. “We should rely not upon a court punishing somebody with a monetary judgment, or an injunction barring them from speech. We should be relying upon more speech, and people should be able to win out in the marketplace of ideas.”

“Effective immunity from liability”?

Like the idea of a marketplace of ideas, however, the principles that underlie the special legal protections for news organizations have come under assault. The news media needs to be reined in, many believe, not afforded special privileges in the public square.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, has also taken direct aim at Times v. Sullivan, backing legislation that would make it easier for plaintiffs to prove actual malice. Calling for “media accountability,” he supports legislation that would also limit the definition of a “public figure,” allowing some plaintiffs to seek damages from the news media under the less stringent standard of negligence.

“We’ve seen over the last generation legacy media outlets increasingly divorce themselves from the truth and instead try to elevate preferred narratives and partisan activism over reporting the facts,” Governor DeSantis said during an event on defamation in February. “When the media attacks me, I have a platform to fight back. When they attack everyday citizens, these individuals don’t have the adequate resources to fight back. In Florida, we want to stand up for the little guy against these massive media conglomerates.”

At least two conservative Supreme Court justices have also attacked the Sullivan decision. Justice Clarence Thomas has criticized the actual malice standard from an originalist perspective, saying not only is the principle not in the Constitution, but it also has no historical precedents.

“The proliferation of falsehoods is, and always has been, a serious matter,” wrote Justice Thomas in a 2021 dissent from a case that dismissed the defamation claims of an Albanian public figure. “Instead of continuing to insulate those who perpetrate lies from traditional remedies like libel suits, we should give them only the protection the First Amendment requires.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch, too, says it is time to take another look at the actual malice standard. He argues that the news media landscape has changed so profoundly since the 1960s that media’s special protections – “an effective immunity from liability,” he wrote – may actually be dangerous in the digital age, in which there are far fewer economic resources to invest in reporting, fact-checking, and editorial oversight.

“What started in 1964 with a decision to tolerate the occasional falsehood to ensure robust reporting by a comparative handful of print and broadcast outlets has evolved into an ironclad subsidy for the publication of falsehoods by means and on a scale previously unimaginable,” he wrote.

There is a certain irony that many conservative thinkers want to scale back a protection that would help Fox in this case, and many conservative media outlets have criticized Governor DeSantis’ efforts.

But there has been a general consensus among legal experts that the evidence presented in the Dominion case just might be enough to clear the high bar of actual malice.

The case has unveiled a host of text messages and emails between Fox personalities and company executives that seem to reveal they did know the allegations were false, calling them everything from “absurd” to “bat---- crazy.”

“I do think this is a clear case of actual malice, which is either knowing falsity or acting with reckless disregard to the truth,” says Ms. Belmas at the University of Kansas. “But even if Dominion wins, it doesn’t fix the underlying problems with the media.”

Last week, the judge took the rare step of sanctioning Fox for withholding evidence during discovery, including recordings by a former Fox employee. And Judge Davis is weighing appointing a special master to investigate potential legal misconduct by the network’s attorneys. On Friday, Fox’s lawyers formally apologized to the judge.

A Fox victory could be less a win for free speech than a symbol of the need for more legal accountability for news organizations.

Mr. Geronimo agrees that the Dominion lawsuit offers “the most compelling evidence of actual malice that I think I’ve seen in a defamation case.” But there are also other compelling reasons to defend Fox’s coverage of issues brought forward by prominent political leaders, which are newsworthy in themselves, he says.

“I don’t think you could find anybody that would disagree that, if we’re using electronic voting systems and they’re compromised, we should be able to talk about that,” Mr. Geronimo says. “We should be able to raise concerns about foreign interference in our elections, whether or not these machines are capable of doing what they say they’re doing, whether or not they’re being tampered with.”

Saudis, Houthis shake hands, but Yemen peace demands more

The Saudi-Iran regional rivalry has hung heavily over Yemen’s tragic civil war. But removing the proxy layer of the complex conflict is not enough to secure peace, analysts caution. That requires including other factions.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Just weeks after China brokered a rapprochement between rivals Saudi Arabia and Iran, a senior Saudi official arrived in Sanaa, Yemen, to shake hands and negotiate with the Iran-backed Houthi rebels, Saudi Arabia’s longtime adversaries.

Years of fighting in Yemen have created one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises and resulted in the deaths of more than 377,000 Yemenis by the end of 2021, the United Nations calculates. The U.N. envoy for Yemen, Hans Grundberg, called the Saudi-Houthi talks “the closest Yemen has been to real progress towards lasting peace.”

Yet even as the Sanaa handshake and talks have sparked hope for progress toward peace, experts say the Saudi-Houthi negotiations focus on just one aspect of a complex conflict and exclude other parties.

“Negotiations between the Yemenis will be imbalanced; it will not be among equals,” says researcher Abdulghani al-Iryani. “The Houthis have no intention of preserving the Yemeni state as a united state; they have no intention of sharing power with anyone in a meaningful way.”

“They want their own state on the territory they control,” he adds, and to ignore the rest of the country’s lands, which “will eventually turn into ungoverned spaces, open for Al Qaeda and Islamic State.”

Saudis, Houthis shake hands, but Yemen peace demands more

Throughout eight years of war in Yemen, the scene that unfolded a week ago appeared unthinkable: A senior official from Saudi Arabia arriving in the capital, Sanaa, to publicly shake hands, smile, and negotiate with sworn enemies – the Iran-backed Houthi rebels who control the capital and the northwest of the country.

Saudi Arabia’s military intervention against the Shiite Houthis began in 2015. Bolstered by extensive American military and intelligence support, it came to include 25,000 air raids, according to a count by the Yemen Data Project. The years of fighting created one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises and resulted in the deaths of more than 377,000 Yemenis by the end of 2021 from both war and hunger, the United Nations calculates.

The Houthis have made Saudi Arabia and its coalition allies pay a high price for their failed bid to return to the capital the internationally recognized government after it was ousted by the Houthis. They have launched more than 1,000 missiles and 350 drones into Saudi territory, increasingly deeply since 2019, prompting Riyadh to search for a way out of its military quagmire.

The accelerated moves follow just weeks after a high-profile rapprochement brokered last month by China between rivals Saudi Arabia and Iran – both of which turned Yemen’s civil war into a proxy battleground to expand their regional influence.

Mohammed al-Bukaiti, a Houthi leader, said on Twitter that a Houthi-Saudi peace deal would be “a triumph for both parties,” and he urged turning “the page of the past.”

And the U.N. envoy for Yemen, Hans Grundberg, told The Associated Press that the talks are “the closest Yemen has been to real progress towards lasting peace.”

Yet even as the Sanaa handshake and talks have sparked hope for progress toward peace in Yemen, bolstered by an initial exchange of some 900 prisoners that began on Friday, experts say the Saudi-Houthi negotiations focus on just one aspect of a complex conflict.

Yemen analysts caution that, while Saudi-Houthi talks are a critical first step toward removing the proxy layer of the conflict, they ignore the other layers of Yemen’s war by excluding other factions. In particular, that includes the internationally recognized government, ruling now from exile in Saudi Arabia, and a separatist militia backed by the United Arab Emirates called the Southern Transitional Council.

Risk of more conflict

The result may be continued conflict among Yemenis, the analysts warn, since any side deal the Houthis reach with the Saudis will give the Iran-backed faction little incentive to abandon their long-held strategic aim of controlling the entire country, or to embrace an inclusive peace process.

“The missile attacks against Saudi Arabia by the Houthis have achieved their goal, which is to pressure the Saudis into surrender,” says Nadwa al-Dawsari, a Yemen expert with the Middle East Institute in Washington.

“This started with the Saudis wanting to completely reverse the [2014] Houthi coup in three weeks, and it ended with senior Saudi officials in Sanaa literally pleading with the Houthis to accept any concessions to simply sign a deal ... to help the Saudis have a face-saving exit out of Yemen,” says Ms. Dawsari.

“The Saudis going to Sanaa is a statement of surrender, a statement of defeat, even if it’s packaged as an attempt to reach peace and end the Yemen conflict,” she says.

In Sanaa, Saudi ambassador to Yemen, Mohammed al-Jaber, met the chief of the Houthi Supreme Political Council, Mahdi al-Mashat, and said the visit aimed to “end the Yemen crisis” with a “comprehensive political solution.”

“There is slight hope that this might lead to resolving some issues, such as salary payments [to civil servants in Houthi-controlled territory] and opening the airports,” says Ms. Dawsari. “But beyond that, Yemenis know this means handing over Yemen to the Houthis, and many are terrified of that scenario.”

“The Saudis and Emiratis have been an obstacle,” she adds. The UAE at first joined the Saudi-led coalition but broke away in 2019 and backed its own militia, resulting in further tension as the UAE and Saudi Arabia have increasingly competed for dominance among Persian Gulf Arabs.

“Even though they helped prevent the Houthis from expanding militarily at the beginning of the war, their competing agendas divided and massively weakened the anti-Houthi camp,” notes Ms. Dawsari.

That has left the Houthis able to extract concessions within the context of U.N. and other peace efforts since 2014, while giving little in return. The Houthis have rejected previous unilateral Saudi cease-fires, but a six-month, U.N.-brokered truce that ended last October still largely holds.

“If the negotiations in their current form succeed, they won’t lead to a durable peace, because the Saudis will have granted de facto recognition to the Houthis ... while excluding other parties,” says Abdulghani al-Iryani, a senior researcher at the Sanaa Center for Strategic Studies, contacted in Amman, Jordan.

“Negotiations between the Yemenis will be imbalanced; it will not be among equals,” says Mr. Iryani. “The Houthis will say, ‘This is what we will give you; take it, or leave it.’”

He says he expects the Houthis to offer an amnesty for the government-in-exile to return, after years of cursing its members as “Saudi mercenaries,” for example, and a symbolic number of Cabinet posts allotted to them in a Houthi-led government, though real power will stay in Houthi hands.

“The Houthis have no intention of preserving the Yemeni state as a united state; they have no intention of sharing power with anyone in a meaningful way,” says Mr. Iryani. “They want their own state on the territory they control,” and to ignore the rest of the country’s lands, which “will eventually turn into ungoverned spaces, open for Al Qaeda and Islamic State.”

Speed of Saudi concessions

After such a heavy investment by Saudi Arabia in the Yemen war, for so many years, analysts have been surprised by the scale and speed of Saudi concessions, which they attribute in part to improving Houthi military capabilities, backed by Iranian expertise.

“By 2019 and 2020, after the increase of Houthi reach into Saudi Arabia, the Saudis were saying, ‘We will withdraw and just let the Yemenis fight it out,’ but it got even more complicated with the Houthis reaching all the way to Riyadh and becoming even more threatening,” says Mr. Iryani.

“I don’t think the Saudis just want to get out, because the Houthis will continue to be a strategic threat to Saudi,” he says.

Dealing with that strategic conundrum may be Saudi Arabia’s biggest concern, as it builds up its Vision 2030, a vast array of spending and building projects the kingdom bills as a “unique transformative economic and social reform blueprint” that is “opening Saudi Arabia up to the world.”

“The Saudis realize that, if they want to exit the conflict, they will have to make great concessions to the Houthis,” says Veena Ali-Khan, a Yemen specialist with the Brussels-based International Crisis Group.

“What is increasingly clear is that the Saudis want to withdraw themselves from Yemen,” says Ms. Ali-Khan. “The Houthis recognize this, so they are trying to extract as many concessions as possible, and it seems to be working.”

The Saudis have been shifting from a military strategy to a diplomatic one.

“What is going to impact their Vision 2030, and prevent tourists coming into the kingdom, is Houthis firing missiles across its border,” says Ms. Ali-Khan.

“So what they see as winning is not necessarily that the Houthis cease to exist, but just ensuring that there is a friendlier Houthi on the border that won’t fire missiles,” she says.

Is kicking out wildcat miners enough to save the Amazon?

Brazil’s president is doubling down on protecting the Amazon – crucial for combatting global warming. But policing illegal activities may not be enough.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Ana Ionova Contributor

In a high-profile crackdown, Brazilian authorities have raided more than 200 wildcat mines – known as garimpo – across the Amazon’s Yanomami reserve in recent weeks, arresting miners and seizing supplies. The aim is to expel some 20,000 illegal miners who have invaded the reserve since 2019, when former President Jair Bolsonaro largely did away with regulations in support of opening the rainforest to mining and ranching.

Placing the environment at the center of his agenda, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has vowed to halt deforestation, punish those illegally exploiting the forest, and reverse the damage done under his predecessor.

Despite the bold strategy, some 330 square miles of forest were razed in the first three months of the year. Observers say attention needs to move beyond crackdowns to include offering economic alternatives for those who turn to this kind of work in the first place.

“The problem in the Amazon is an economic one – and deforestation is a symptom of it, not the cause,” says Danicley de Aguia, a campaigner with Greenpeace Brazil. “You might be able to slash the deforestation rate again. But if there’s no other option, at the first sign of weakening enforcement, it jumps back up again.”

Is kicking out wildcat miners enough to save the Amazon?

Deep in the Brazilian Amazon in early February, wildcat miners sped down the Uraricoera River slicing through the Yanomami Indigenous reserve in three motorboats packed with barrels of gasoline and plastic foam boxes of meat.

The supplies were meant to fuel an illegal gold mine tucked in the heart of Brazil’s largest Indigenous territory. But their journey was abruptly cut short. “Everyone stop!” shouted an armed officer as police overtook the men’s boat. They raised their arms in surrender.

“There’s so much food here. ... All of these sacks here are full of food,” one officer said later, as he examined the supplies his team seized. “All the while the Yanomami are starving.”

In a high-profile crackdown, Brazilian authorities have raided more than 200 wildcat mines – known as garimpo – across the Yanomami reserve in recent months, arresting miners, seizing supplies, and setting machinery ablaze. The aim is to expel some 20,000 illegal miners who have invaded the reserve since 2019, ushering in disease, deforestation, hunger, and conflict – and transforming the Yanomami into a symbol of the widespread destruction gripping the world’s largest rainforest.

The offensive is part of a plan by President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to pivot toward protection in the Amazon, after years of rapid destruction under the administration of Jair Bolsonaro. Placing the environment at the center of his agenda, Lula, as the president is commonly referred to, has vowed to halt deforestation, punish those illegally exploiting the forest, and reverse the damage done under Mr. Bolsonaro, who avidly supported opening the Amazon to mining and ranching.

“The commitment is, by 2030, to have zero deforestation in the Amazon. And I will pursue this with all my might,” Lula said earlier this year.

Keen to send a clear message from the start, Lula made expelling the wildcat miners from the Yanomami reserve one of his first major acts since taking office on Jan. 1. He has promised to carry out similar operations in at least six other Indigenous reserves in the coming months.

Despite the bold strategy, some 330 square miles of forest were razed in the Amazon in the first three months of the year, data from Brazil’s space agency showed earlier this month, marking the second-highest rate of deforestation on record and suggesting that those bent on destroying the rainforest have little intention of giving up. As Lula doubles down on protecting the forest, observers say attention needs to move beyond crackdowns on illegal mining to include offering economic alternatives for those who turn to this kind of work in the first place.

“This change in government feels like a sigh of relief,” says Martha Fellows, a researcher at the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM). But, she adds, “the culture of destruction still persists. Unfortunately, this is a culture that doesn’t disappear overnight.”

Decades-old battle

From above, the Yanomami reserve looks like a patchwork of emerald canopy and vast craters filled with murky pools of wastewater. There, the tussle over land can be traced back to the 1970s, when loggers and miners first began trickling in.

By the 1990s, when federal authorities declared the area an Indigenous reserve, it was already overrun by some 40,000 illegal miners –about twice the number thought to be operating there today.

João Moreira arrived in Yanomami in the late 1980s, hoping to strike it rich in a gold mine. It was hard, punishing work; many of the men who toiled alongside him were poor and illiterate, with few other economic prospects.

“Those who come to the Amazon are living through hardship and searching for opportunity,” he says. “And the garimpo gives them that opportunity to dream and to get ahead in life. It’s like you’ve won the lottery.”

He remembers flying from the state capital Boa Vista to the Indigenous land on a small plane, over the dense forest cover, toward the illegal landing strip near the mine. “There was nothing there, just jungle, jungle, jungle” he recalls in a phone interview from Planalto da Serra, in the state of Mato Grosso, where he now lives.

Police tried to expel Mr. Moreira’s group once, but the men just came back when the dust settled. Finally, in 1992, authorities succeeded in removing the outsiders, including Mr. Moreira, and returning the land back to the tens of thousands of Yanomami people who have lived there for centuries, some of them in voluntary isolation from the outside world.

But in 2019, as Mr. Bolsonaro moved to loosen environmental policing, illegal miners saw an opportunity to descend on the territory once again. “The Brazilian state has an obligation to protect Indigenous lands,” says Edinho Batista, coordinator of the Indigenous Council of Roraima, where the Yanomami reserve is located. “But what we saw during the last four years was the exact opposite. That’s how we got to this crisis.”

In the wake of the latest crackdown in the reserve, many illegal miners have voluntarily left. Mr. Moreira himself left the gold trade many years back, opening a construction firm. But he doubts the miners pouring out of the reserve now will give up for good.

“They’re just going to come back, or go to another part of the Amazon,” he says. “Many don’t know how to do anything else.”

A new chapter

Under Mr. Bolsonaro, deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon soared to its highest level in 15 years, as emboldened intruders rushed to raze and burn slices of the forest. Mr. Bolsonaro regularly railed against environmental protections, arguing they only got in the way of development, and he gutted agencies of the resources and staff needed to protect both the rainforest and the people who depend on it. Local bases staffed by environmental enforcement agents shuttered across the Amazon, leaving a vacuum that criminals easily exploited.

On the international stage, Lula has made big promises to crack down on deforestation, to punish those encroaching on the forest, and to turn Brazil into a leader in the global scramble to avert a climate crisis.

“The Amazon has one of the largest carbon stocks in the world, so it’s crucial for the regulation of the climate,” says Ms. Fellows of IPAM. “We do have to think globally. ... The Amazon isn’t relevant just locally to us.”

Lula’s track record offers reason to hope: During his first two terms in office, between 2003 and 2010, the leftist leader helped slash deforestation by 80% and turned Brazil into a global champion in forest conservation.

Since returning to office, he has revived an international fund that once financed conservation projects, but was suspended in 2019 amid soaring deforestation, freezing over $500 million in aid.

He has toughened up policing, too. In the first three months of the year, fines for deforestation jumped 219%, according to the Ministry of Environment. And in the Yanomami reserve, agents have so far seized 84 barges and boats, two planes, 172 generators, a mining rig, and 3,000 gallons of fuel.

“You’re sending the message that garimpo won’t be tolerated – and all of a sudden, illegal miners start thinking twice about whether it might be bad for business,” says Danicley de Aguia, a campaigner with Greenpeace Brazil.

Still, environmentalists say bold crackdowns may not be enough. Effectively policing the Brazilian Amazon, which stretches across millions of miles, is notoriously difficult – and costly. It can take environmental agents days, whether by motorboat or rough dirt road, to reach illegal mines and ranches tucked deep in the jungle.

Offering alternatives

To truly root out illegal extraction in the Amazon, Mr. de Aguia says, the government must develop economic alternatives that make preserving the forest more attractive.

“The problem in the Amazon is an economic one – and deforestation is a symptom of it, not the cause,” he says. “You might be able to slash the deforestation rate again. But if there’s no other option, at the first sign of weakening enforcement, it jumps back up again.”

The Amazon is one of Brazil’s most politically and economically neglected regions, with millions living below the poverty line. With huge swaths isolated from the rest of the country, many residents struggle to access basic services like health care and schooling.

Lula has advocated for investing in green jobs and exploring the rainforest for new ingredients that can be used in medicines and cosmetics. He says communities can earn income from the forest by selling exotic fruits and nuts, but the plan has been criticized for being vague.

“We need economic solutions in the Amazon,” says Mr. de Aguia. “It’s always the hand of the poor man that picks up the chainsaw.”

Difference-maker

Dig It! Coffee Co. serves independence in a cup

People with disabilities often have limited options for advancement. A Las Vegas employer aims to pair dignity with opportunities for growth.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

When Taylor Chaney graduated from college, opportunities opened up. The same was not true for her younger sister, Lindsay, who has Down syndrome.

After Lindsay aged out of the school system, her family realized there were not many quality options for her to continue growing and gaining independence as an adult.

Mrs. Chaney spent a year researching the types of programs available for people with disabilities in Nevada and neighboring states. She found little.

In 2018 she opened The Garden Foundation, a nonprofit that provides personalized programs and services, such as art therapy, sign language courses, and fitness classes.

Out of that foundation, which so far has served about 50 adults, grew Dig It! Coffee Co., a Las Vegas cafe that employs adults with disabilities, providing a sense of dignity and competitive wages that can be difficult to find elsewhere.

Alecia Fife says Dig It has been a “blessing” for her daughter, Allie, who works as an assistant barista and has gained social confidence and some financial independence.

“It’s just done a lot for our daughter,” she says. “It’s been amazing to watch.”

Dig It! Coffee Co. serves independence in a cup

Before the customer even reaches the counter, Taylore Sears greets her with gratitude.

“Thank you for coming in!” Ms. Sears says from behind the register at Dig It! Coffee Co. in downtown Las Vegas.

The woman orders a chocolate-strawberry latte, prompting Ms. Sears, an assistant barista, to ask the follow-up questions coffee connoisseurs have come to expect: “What kind of milk would you like?” and “Would you like it hot or iced?”

The interaction breezes along with pleasantries exchanged as the woman pays and waits for her warm beverage. It’s a scene that unfolds at coffee shops across the globe, except in this case, the business has a purpose that extends far beyond just serving customers. Dig It employs adults with disabilities, providing a sense of dignity and competitive wages that can be difficult to find elsewhere.

The coffee shop opened in September, bringing to life a vision long held by its owner, Taylor Chaney. The Las Vegas native has made it her mission to provide more opportunities for people with different abilities, like her younger sister, Lindsay, who has Down syndrome.

“I get applications daily,” she says. “It’s amazing, but it’s also heartbreaking because I knew that there was a large gap, but it is insurmountable.”

Mrs. Chaney’s advocacy work in the disability community began after Lindsay aged out of the school system. Her family realized there were not many quality options for Lindsay to continue growing and gaining independence as an adult. After a negative experience at a day program, the women’s father retired so he could stay home with Lindsay. That didn’t sit right with Mrs. Chaney, who had attended college and was working as a sales manager for an insurance broker. Opportunities and choices that had fallen her way after graduation did not exist for Lindsay.

So Mrs. Chaney turned down a relocation offer with the insurance broker and spent a year researching the types of programs available for people with disabilities in Nevada and neighboring states. Her takeaway: Not much had been done to move the disability community forward in 50 years.

In 2018, just months after their father suddenly died, Mrs. Chaney opened The Garden Foundation. The nonprofit provides personalized programs and services, such as art therapy, sign language courses, and fitness classes.

The organization has served about 50 adults, which Mrs. Chaney says is a smaller number by design. She says The Garden Foundation aims to go “really deep” with clients in what she describes as “boutique, high-quality care.”

“They’re not just a person within the system,” she says. “We know each other’s birthday and what they like and don’t like.”

As part of its life skills programming, The Garden Foundation launched a coffee cart to foster money handling and customer service skills, Mrs. Chaney says. Clients operated Blooms & Brew – a nod to the fresh flowers they sold alongside coffee – in the same office building as the nonprofit.

It was a hit with both customers and clients, Mrs. Chaney says, inspiring a search for a brick-and-mortar location.

Jonathan Zamora, owner of a distributor called Sin City Coffee & Beverage, helped her find Dig It! Coffee Co.’s spot in a trendy area downtown known as the Arts District. Nearby businesses include a vegan taco restaurant, a vintage clothing store, antique shops, art galleries, bars, and other eateries.

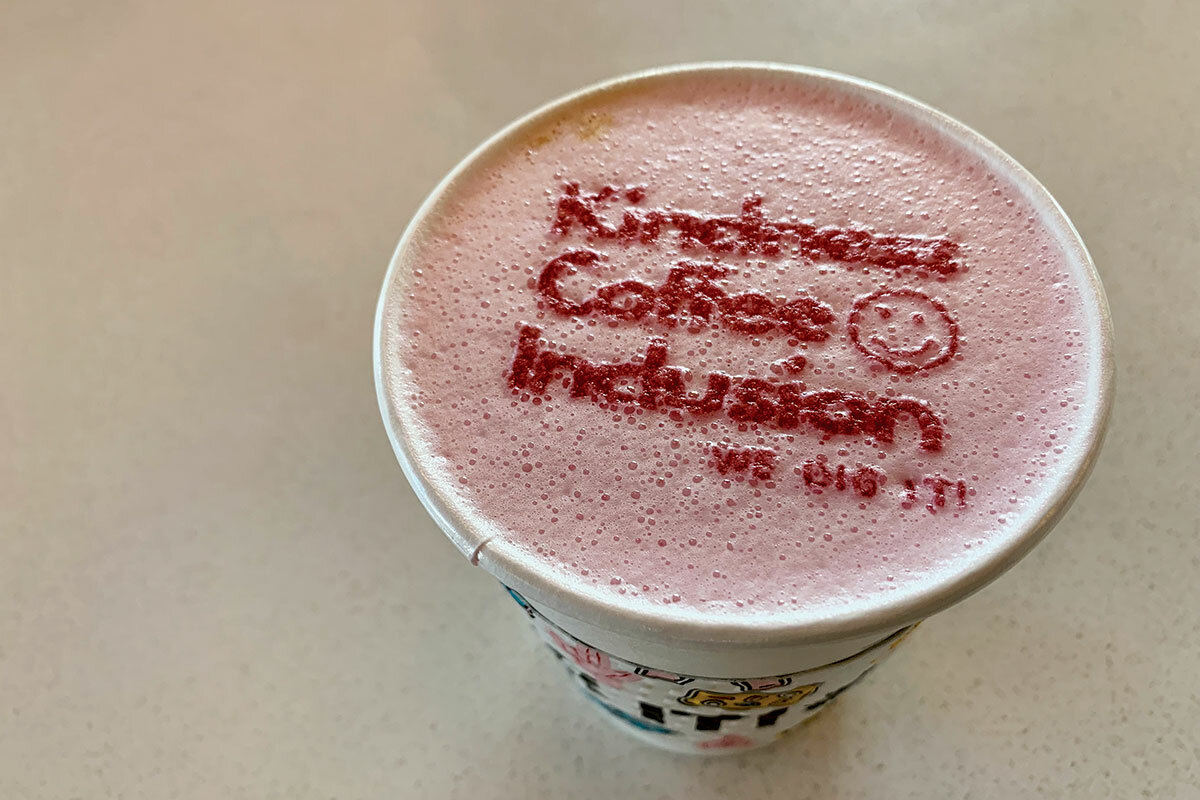

Positivity abounds in Dig It, where flowers, smiley faces, and a light-up sign that says “Not Typical” decorate the interior. The shop’s motto – “Kindness, Coffee, Inclusion” – appears as art on the tops of frothy beverages.

Mr. Zamora describes Mrs. Chaney as someone who “never stops” in her pursuit to build a more inclusive community.

“She has big, big possibilities to be as successful in business and also be successful in changing people’s lives,” he says.

Apart from giving people with disabilities a nurturing work environment where they can grow and learn, Mrs. Chaney says she is also proud to pay the assistant baristas above minimum wage. They earn $10.50 per hour, plus tips, which usually brings that rate up to $15 or $16. That can be difficult to find, as the U.S. Department of Labor allows businesses to pay subminimum wage to employees with disabilities.

Alecia Fife says Dig It has been a “blessing” for her daughter, Allie, who works as an assistant barista and has gained social confidence and some financial independence. Ms. Fife filmed Allie beaming with pride as she received her first paycheck.

“It’s just done a lot for our daughter,” she says. “It’s been amazing to watch.”

Allie typically works here two days a week, taking customers’ orders from behind the counter. She has learned how to make coffee and make friends – pointing out that the best part of her job is “the people I work with.”

Ms. Sears, the assistant barista, has also honed her skills operating the point-of-sale system, and she doesn’t shy away from recommending various menu items. Her favorite part of the job? “Talking to customers,” she says.

The benefits run both ways, says Mrs. Chaney, adding that she enjoys watching customers, some of whom haven’t spent time around people with disabilities, experience that interaction. She hopes that one day the coffee shop is less the exception and more the norm when it comes to hiring people with disabilities.

“I love that everyone’s heart can be touched in a different way,” she says.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Despite Sudan fighting, a society reshapes itself

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Just a few days ago, civil society and military leaders in Sudan were poised to set the African nation on a carefully negotiated path back to democracy. Instead the country’s two top generals, who joined forces to seize power 18 months ago, have turned on each other.

The fighting that erupted Saturday comes at a time when the Horn of Africa is already dealing with multiple security challenges. Yet rather than marking the end of popular hopes for a return to civilian government in Sudan, the outbreak between the rival military factions shows how deeply rooted those democratic aspirations have become. As a doctor in Khartoum, the capital, told Le Monde today, “This is not our war.”

The outbreak of fighting in Sudan has raised united calls from the international community for a swift return to peaceful negotiations. But for Sudan’s civil society groups, the power struggle between two warring generals is almost secondary. Their work of building a society shaped by democratic values goes on.

Despite Sudan fighting, a society reshapes itself

Just a few days ago, civil society and military leaders in Sudan were poised to set the African nation on a carefully negotiated path back to democracy. Instead the country’s two top generals, who joined forces to seize power 18 months ago, have turned on each other.

The fighting that erupted Saturday comes at a time when the Horn of Africa is already dealing with multiple security challenges. Yet rather than marking the end of popular hopes for a return to civilian government in Sudan, the outbreak between the rival military factions shows how deeply rooted those democratic aspirations have become. As a doctor in Khartoum, the capital, told Le Monde today, “this is not our war.”

Across Africa, an uptick in coups in recent years has strengthened pro-democracy movements and efforts to instill democratic values in African armed forces. In the past five years, 26 African countries have joined in an association of parliamentary committees working to strengthen civilian military oversight. African civilian and military leaders, meanwhile, are working through regional security blocs and the African Union to professionalize armed forces under civilian command.

Those efforts, the Africa Center for Strategic Studies notes, reflect an attempt to earn public trust by instilling values such as “integrity, honor, expertise, sacrifice, and respect for citizens” in African militaries. They mirror public attitudes. The latest Afrobarometer survey of attitudes about democracy found that, across 34 countries, 68% of Africans prefer democracy to any other system of government, while large majorities reject military rule (74%) or one-person rule (77%).

Tellingly, in countries where militaries have seized power in recent years, the generals have felt compelled to promise transitions back to democracy. In Sudan, one of the warring generals admitted last year that the coup he backed in 2021 was wrong. The other said, “soldiers belong in the barracks, and parties go to elections.”

Negotiated transitions in countries that have fallen recently under military rule have met repeated delays and obstacles. A constitutional referendum in Mali, for instance, was indefinitely postponed in March. Yet for the democratic forces set in motion by African coups in recent years, such setbacks have strengthened resolve.

“The Malian population has enormous energy and appetite for a change,” Korotoumou Thera, executive director of a Malian civil society group for women, told the United States Institute of Peace last week. Organizations like hers, she said, “act as cement in the consolidation of peace and security.”

The outbreak of fighting in Sudan has raised united calls from the international community for a swift return to peaceful negotiations. But for Sudan’s civil society groups, the power struggle between two warring generals is almost secondary. Their work of building a society shaped by democratic values goes on.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Spirals of sadness aren’t inevitable

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

We can rely on the light of God, good, to lift us out of the darkness of hopelessness or unhappiness – as a young woman experienced after facing recurring periods of sadness.

Spirals of sadness aren’t inevitable

Recent reports have brought to attention that many teenage girls are feeling a greater degree of sadness and hopelessness. For instance, a teen telling her story on a program I was watching spoke of finding herself becoming swallowed up in looking for approval on social media. Not feeling able to pull herself away, she began to do things that negatively affected her well-being, and her life began to spiral downward. Thankfully, she saw her need for help, and with much support from others, she was able to come out of the darkness.

The need for healing of this issue really struck me. So right then I reached out to God in prayer, as I have found this helpful so many times in my study and practice of Christian Science.

The words “circle harmoniously” came to me. I recognized this phrase as being from “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science and of the Monitor, so I looked it up and found this: “Day may decline and shadows fall, but darkness flees when the earth has again turned upon its axis. The sun is not affected by the revolution of the earth. So Science reveals Soul as God, untouched by sin and death, – as the central Life and intelligence around which circle harmoniously all things in the systems of Mind” (p. 310).

What a comfort to consider God – who is all-powerful, all-present good – as divine Mind and Life itself, and the true center of existence. As God’s children, we are in fact the spiritual expression of God’s love, harmony, and wisdom. Our true identity never includes sadness and hopelessness, because there is no place for these – either as cause or effect – in the infinite divine Life.

What strength lies in the spiritual fact that we are subject to the governing law of Life! It gives us a sure foundation to reject and overcome influences and thoughts that aren’t consistent with the joy and harmony of “the systems of Mind.” Such thoughts don’t come from God, and therefore don’t have the power they may seem to.

Many years ago as a young adult, I experienced periods of sadness. Although there wasn’t one thing that seemed to bring these on, I would find myself overcome with a sense of darkness, as though a shade had been pulled down in a room and no light could shine in.

I took heart in the biblical promise that “God is light, and in him is no darkness at all” (I John 1:5). This gave me the spiritual authority and impetus to reject the sadness as not coming from God, and therefore not an inevitable part of my thinking. When I prayed this way, the mental shade would lift and I would feel a joy pour in like the warmth of the sun.

This joy felt so powerful that I knew it was more than a human emotion. It was from God, and something that we all reflect naturally as God’s children. God being the only legitimate Mind and Life, the only governing cause or determinant of our identity, the natural outcome is joy and peace that aren’t dependent on material circumstances.

As I continued praying about these episodes, they ultimately stopped for good.

Even when sadness feels overwhelming, God – infinite good – remains untouched, and our nature as His deeply loved children – expressing divine goodness and joy – remains unaltered. A downward spiral is not inevitable for anyone – of any demographic. We can each let God’s love and guidance into our heart, opening the way to a firmly rooted contentedness and peace that balances and uplifts all our activities.

Viewfinder

Fleet street

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Tomorrow, we’ll have news from Israel, where Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is under intense pressure over security, extremist threats, and his government’s stability. And we’ll have some poetry collections to recommend as well.