- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Across faiths, a call to honor your neighbor

Husna Haq

Husna Haq

Ding-dong!

It was the mid-’90s, in my childhood home in rural central New York, where we didn’t frequently get visitors. I peeked out the window to find a pair of suit-clad Jehovah’s Witnesses, and promptly retreated – from what I’d heard, most people avoided them. My dad opened the door wide, smiled, and welcomed them into the living room, offering them cups of tea. They shared their faith; then my dad shared his, Islam. The visit lasted close to an hour, and soon became a regular occurrence anytime Jehovah’s Witnesses knocked.

As a child, I would roll my eyes at the intrusions. Now, I treasure the openness, curiosity, and sincerity of both those visitors and my dad. Today, door-knocking is viewed with suspicion, and tragically, occasionally met with violence. Yet, this memory reminds me that faith traditions are rich with guidance on honoring the visitor and the neighbor, for good reason.

The early Jews’ experience as slaves in Egypt provides a fount of lessons in morality and compassion, evident in this passage from Leviticus: “You shall treat the stranger who sojourns with you as the native among you, and you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.” Perhaps most famous is the foundational commandment, “Love thy neighbour as thyself” (Leviticus 19:18).

In the New Testament of the Bible, Jesus tells the story of a Samaritan who cares for an injured traveler left for dead on the roadside – and ignored by two other passersby. “Which now of these three, thinkest thou, was neighbour unto him that fell among the thieves?” Jesus asks, receiving the response, “He that shewed mercy on him.” His advice? “Go, and do thou likewise” (Luke 10:36-37).

In Islam, neighbors and guests hold a place of high honor with specific and practical rights, including visiting them when ill, sharing food and gifts, and even tolerating annoyances. Muhammad said, “None of you will have faith until he loves for his brother, and his neighbor, what he loves for himself,” and “He is not a believer whose stomach is filled while his neighbor goes hungry.”

Across faiths, the advice is simple, yet profound: Compassion builds trust and community, values we can use today.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Debt limit: A political chasm over fiscal responsibility

Debt limit negotiations have often been framed around the espoused goal of compelling greater fiscal discipline. But this round is particularly high-stakes, with each side digging in.

President Joe Biden has called congressional leaders to the White House tomorrow to try to avert a default on the $31.5 trillion national debt, which could occur as soon as June 1.

“Somebody needs to go in there with a plan” – one that is realistic, not ideological, says former Democratic Sen. Kent Conrad, who helped negotiate a resolution to the 2011 debt limit crisis.

“Republicans don’t want to raise revenue. Democrats don’t want to touch entitlements. The hard reality is you have to have some of both,” adds Mr. Conrad. “That takes a bipartisan commitment, and a bipartisan approach.”

The scale of the problem is hard to fathom, but economists testifying at a recent congressional hearing tried to put it into perspective: A million dollars in $100 bills could fit in a backpack; by comparison, America’s $31.46 trillion debt would take up 31½ football fields with construction pallets stacked two deep, and each containing bills totaling $100 million. Another expert noted that within 30 years, interest on the debt could consume 70% to 100% of U.S. revenue.

The House Problem Solvers Caucus has proposed raising the debt ceiling through the end of 2023 to avoid default, and appointing a commission to get the nation’s fiscal house in order.

Debt limit: A political chasm over fiscal responsibility

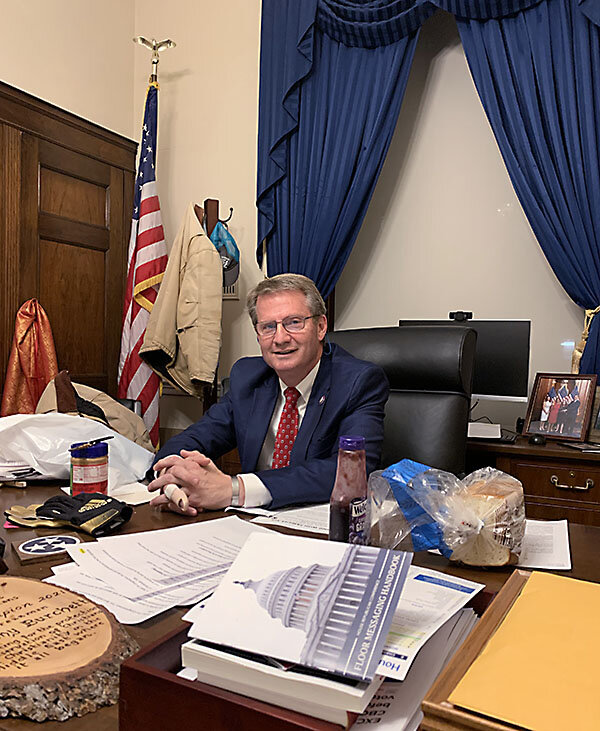

As the United States hurtles toward default on its record debt, Tennessee Rep. Tim Burchett is eating peanut butter and jelly sandwiches at his desk for dinner.

He doesn’t come from money. His parents – survivors of the Depression – lived within their means. So has his state, which is constitutionally mandated to balance its budget. Now he’s calling for the nation to do likewise, armed with a squirt bottle of Welch’s grape jelly in a town where dining out is de rigueur.

Congressman Burchett was one of four House Republicans who voted against a GOP bill two weeks ago that would raise the national debt limit by $1.5 trillion in exchange for spending cuts to help get the nation’s fiscal house in order. The debt currently stands at just under $31.5 trillion.

“I did not vote for [raising the debt limit] under Trump, and I thought it’d be very disingenuous if I did it here,” says Representative Burchett in a phone interview, pointing out that even under this latest Republican plan, the debt would continue to grow by about $1.5 trillion each year. “It’s going to destroy this country.”

Tomorrow congressional leaders will meet with President Joe Biden at the White House to try to avert a default on the debt, which would occur if the limit isn’t raised and could have long-term consequences for the U.S. economy and its global standing. The deeper issue is how to bring spending and revenue into better balance, as America’s rising debt – blamed on everything from the war on terror to Trump tax cuts to pandemic spending – exceeds World War II proportions for the first time.

“Somebody needs to go in there with a plan – and a plan that is realistic, not a plan that is ideological,” says former Sen. Kent Conrad, a North Dakota Democrat who helped negotiate a resolution to the last major debt limit crisis in 2011 as Senate Budget Committee chairman.

“Republicans don’t want to raise revenue. Democrats don’t want to touch entitlements. The hard reality is you have to have some of both,” adds Mr. Conrad, who now co-chairs the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Commission on Retirement Security and Personal Savings. “That takes a bipartisan commitment, and a bipartisan approach.”’

At an impasse

The near-term need – to boost the debt limit – doesn’t necessarily require a larger fiscal deal to be cut, though the two have often been paired. For Republicans demanding spending restraint, one option is to agree to a debt limit hike now and then pin their demands to other legislation, such as on appropriations later this year.

But for now the parties appear to be at an impasse.

House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, whose caucus includes hard-line fiscal conservatives who opposed raising the debt ceiling or wanted deeper spending cuts in exchange for doing so, has little wiggle room for bargaining. He got House Republicans to pass the Limit, Save, Grow Act on April 26 – albeit with just one vote to spare. But Democrats firmly oppose the GOP debt limit bill, which has virtually no chance of passing the Democrat-led Senate.

Unless a different solution is reached, the Treasury Department is expected to default on its obligations on or around June 1. Already the Treasury has been using “extraordinary measures” to pay federal bills, after hitting the congressionally mandated debt limit in January.

Experts warn that that would tarnish America’s creditworthiness, raise interest rates on everything from mortgages to car loans for years to come, and perhaps plunge the nation into a recession. It could also prompt a global shift away from the dollar as the currency of choice.

“Crashing the global economy if we don’t get what we want isn’t policymaking,” said Senate Budget Committee Chairman Sheldon Whitehouse, a Rhode Island Democrat, at a hearing May 4. “It’s hostage-taking.”

Nearly 32 football fields of $100 bills

A million dollars in $100 bills could fit in a school backpack; by comparison, the U.S. debt of $31.46 trillion would take up 31½ football fields with construction pallets stacked two deep and each containing bills totaling $100 million, said Jason Fichtner, chief economist of the Bipartisan Policy Center, at the Senate Budget Committee hearing last week.

At the same hearing, Brian Riedl of the Manhattan Institute said that current deficit projections would add $20 trillion to the debt over the coming decade, with the long-term picture even more sobering.

According to a forecast from the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, baseline deficits would rise to $114 trillion – mostly due to Social Security and Medicare shortfalls – over the next 30 years. Within that period, it would take half the nation’s tax revenues just to pay the interest on the national debt. If interest rates rise, interest costs could rise to 70% to 100% of tax revenues. That would be akin to having to put one’s full salary toward interest on a credit card, leaving no income to pay off the card or even cover purchases – thus adding to the bill, and the amount of interest owed.

Democrats see the solution as raising tax revenues, including by giving the IRS $80 billion for enhanced auditing power, among other things, and by proposing new taxes on the super-rich. Republicans see the main problem as runaway spending. In their Limit, Save, Grow debt limit bill, they proposed cutting most of the $80 billion for the IRS, repealing clean energy provisions and tax incentives, rescinding unspent COVID-19 relief funds, and increasing work requirements for recipients of Medicaid and other benefit programs.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the bill would save $4.8 trillion over the next decade. That would reduce projected deficits to $1.52 trillion per year, down by $480 billion per year. National debt held by the public would still grow, however, from 98% to 106% of gross domestic product – though less than the 118% currently projected.

The budget that President Biden proposed in March would cut the deficit by $3 trillion over the coming decade by raising revenues, including through a new minimum tax on billionaires and a repeal of Trump tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy, according to a White House fact sheet.

A possible solution

Former Senator Conrad, who was involved in multiple negotiations over the debt limit during his two decades in the Senate, says that the contours of the negotiations have been well defined for years. “Same song, second verse,” he half-jokes.

One solution he sees would be for members of Congress to raise the debt limit for a limited period and appoint a commission to work out the thornier issues of how to balance U.S. fiscal policy. Indeed, the House Problem Solvers Caucus has proposed just that, raising the debt ceiling through the end of the year while appointing a commission “to stabilize long-term deficits and debts.”

The Indian couple helping thousands of sugarcane cutters

Fighting modern slavery takes courage. One couple is using every tool available – including education – to combat bonded labor in India’s mammoth sugar industry.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Haziq Qadri Contributor

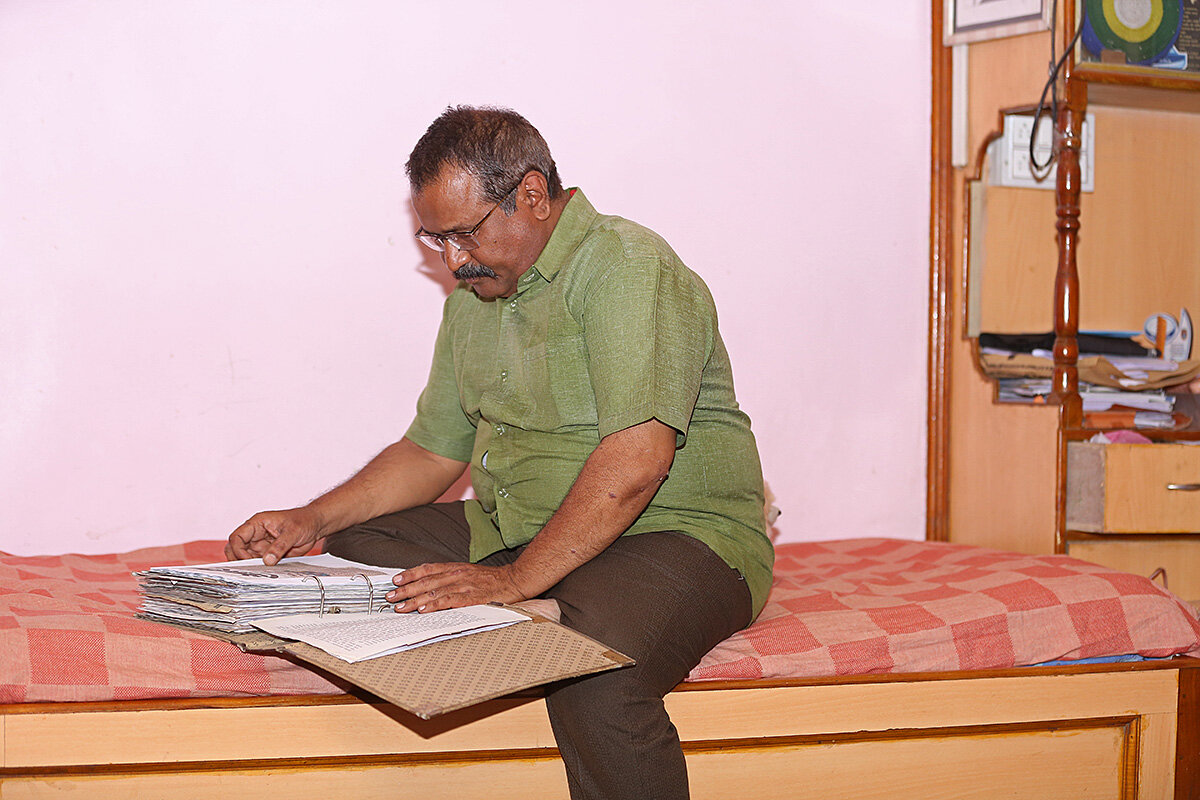

At home in the congested town of Beed, Ashok Tangade flips through the old case files of sugarcane cutters whom he and his wife, Manisha Tokle, helped rescue from bonded labor.

India is one of the world’s largest sugar exporters, with more than a million sugarcane cutters in Maharashtra state alone. Local reports highlight rampant issues of child labor, sexual violence, and debt bondage. Many sugarcane cutters in Beed are migrant workers, lured to the fields with the promise of higher wages and better working conditions. Once on-site, they can be trapped in predatory loans, creating a vicious cycle of bonded labor that can span generations if left unchecked.

Lawyer Sanjoy Ghose describes this as “the worst form of modern slavery,” and one explicitly outlawed under India’s 1976 Bonded Labour Systems (Abolition) Act. For decades, Mr. Tangade and Ms. Tokle have been working closely with sugarcane cutters across Maharashtra, partnering with police to extract laborers from abusive farms, and also educating them about their rights and how to fight for their own freedom.

“Since these laborers were mostly illiterate ... they would assume they were legally bound by the bond,” says Mr. Tangade. “Now the workers realize that they too are entitled to their rights, and that they cannot be held hostage by anyone.”

The Indian couple helping thousands of sugarcane cutters

In the early 1990s, Masu Avadh was chopping sugarcane in India’s Maharashtra state, trying to work off the debt his grandfather and father had both died trying to repay. Feeling ill, Mr. Avadh left the farm without informing the owner to buy medicine. When he returned, he was beaten.

That’s when a young couple intervened.

“When we learnt Avadh ... was working to repay the loan his grandfather had taken, we informed the police,” says Ashok Tangade, flipping through the old case files of sugarcane cutters he and his wife, Manisha Tokle, helped rescue from bonded labor. At their home in the small and congested town of Beed, the now middle-aged duo recalls how Mr. Avadh was freed not only from the farm owner’s clutches, but also from the familial debt.

Mr. Avadh is one of thousands of bonded laborers assisted by Mr. Tangade and Ms. Tokle, but many more remain in bondage – a practice illegal in India since the late 1970s.

About 50 million people work in India’s sugar fields, cutting cane for major international companies. There’s a paucity of precise data on bonded labor in sugar cane production specifically, but a 2019 study by the United Nations Development Programme and the Coca-Cola Company notes that most of India’s bonded laborers work in agriculture, and anecdotal evidence shows India’s sugar industry marred by exploitation and debt bondage. For the past three decades, Mr. Tangade and Ms. Tokle have been working closely with sugarcane cutters across Maharashtra, helping extract laborers from abusive farms, and also educating them about their rights and how to fight for their own freedom.

“Since these laborers were mostly illiterate and unaware of their rights, they would assume they were legally bound by the bond, and would work most of their lives for the contractor in abject conditions, bearing the atrocities,” says Mr. Tangade. “Now the workers realize that they too are entitled to their rights, and that they cannot be held hostage by anyone just because of their socio-economic status.”

Trouble in India’s sugar fields

India is one of the world’s largest sugar exporters, boasting over 700 operational sugar factories with a crushing capacity of about 34 million metric tons. There are more than a million sugarcane cutters in Maharashtra, and during the sugarcane season, many travel to Beed to work 15-hour days in extreme conditions, earning less than $4 daily. Reports have highlighted rampant issues of child labor, forced hysterectomies, and sexual violence, as well as debt bondage.

Indeed, a study of Maharashtra’s Beed region shows that 67% of the sugar cane cutters are indebted.

Some are lured to the fields with the promise of higher wages and better working conditions, but once on-site, workers are not allowed to take a day off and face fines for any leaves. Their loans are often not repaid due to either high interest rates or the lender’s abuse of power, resulting in a vicious cycle of bonded labor – a cycle that can span generations.

Senior Indian lawyer Sanjoy Ghose describes this kind of bondage as “the worst form of modern slavery,” and one explicitly outlawed under India’s 1976 Bonded Labour Systems (Abolition) Act. The law was designed, he explains, to end the multigenerational practice of trapping people in labor, and prevent cases like that of Mr. Avadh.

Yet advocates say bonded labor is still rampant in the sugar industry, as recent incidents in Maharashtra have shown.

A daring rescue

Last December, three children aged 13-14 were trafficked from central India’s Madhya Pradesh to Beed by a labor contractor who promised each child $60 and a mobile phone. The parents were not informed.

For weeks, they worked in sugarcane fields. Most days, they were given only one meal, and they were barred from speaking to their parents.

When they demanded to go home, things only got worse. “The contractor beat us up and said we could not leave until we finished the work,” says Sagar, one of the children. “We were scared.”

When a source tipped off Mr. Tangade to the children’s situation, the couple dispatched a team of police to relocate them to a safe house. There, police took their statements and called their parents. After registering a criminal case against the accused labor contractors, the children were sent home.

Sagar’s father, Bachnan Ulkey, says it was only because of Mr. Tangade’s efforts that the rescue was a success. When he and other parents arrived in Beed to retrieve their kids, they learned that the couple has been doing this for years.

“We are extremely thankful to Tangade and Tokle for rescuing Sagar,” says Mr. Ulkey. “This is not the first time they have rescued kids.”

Decades of advocacy

The duo has been working to eradicate caste-based bonded labor in Maharashtra since 1989. Back then, labor contractors or farm owners would hire the lower-caste or tribal laborers and make them sign an illegal bond.

Ms. Tokle says when they set out to work on behalf of sugarcane cutters, “our primary focus was to rescue them from bonded labor with the help of the police and court. It was a risky job because the factory owners were politically connected.”

Every job is different. Often, they start by going to the police, but if that doesn’t work, they use the media to raise awareness about the case. Other times, the couple reaches out to the sugarcane cutter directly and helps them advocate for themselves against their employer.

As busy as the couple is, there are signs of progress. One of the challenges they face is that sugarcane cutters are part of India’s vast informal workforce, and they can have difficulties accessing welfare programs. So the couple was pleased by the state government’s April 2022 announcement that over a million of Maharashtra’s sugarcane cutters will be issued identity cards, and that their children will be able to stay in hostels during the migration season to avoid academic interruption.

“The step was significant for the millions of sugarcane workers as it will help them access the welfare schemes and their children will get education,” Ms. Tokle says.

Ms. Tokle and Mr. Tangade also organize camps every year where they educate sugarcane cutters about their rights, and in 2019 the couple, along with sugarcane cutters and other advocacy groups, pressured the government into taking action to control the practice of unwanted hysterectomies.

Mr. Ghose, the lawyer, notes that eradicating bonded labor will require deeper, more systemic change. He wants to see local banks provide better access to loans for the rural poor to meet their daily needs so that they don't fall into debt traps, as well as more vigilant enforcement of the law.

But until then, Beed’s sugarcane cutters can count on Ms. Tokle and Mr. Tangade being in their corner.

“As long as we live, we will keep working,” says Mr. Tangade.

A letter from Moscow

Seeking asylum in the US? Make sure your cellphone is charged.

Seeking asylum is one of the most fraught moments in an individual’s life. Now the U.S. requires asylum-seekers to begin the process with a phone application that could exacerbate inequalities.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Seeking asylum is difficult in the best of times. Now the U.S. has turned to tech to streamline the process.

Since Jan. 12, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has required individuals seeking to enter the U.S. under exemptions to Title 42 – a temporary pandemic-era law that has been used to expel asylum-seekers and migrants over the past three years – to use their new CBP One mobile application.

Many critics say that the app, which will persist after Title 42 ends this week, is widening the digital divide. It demands asylum-seekers have access to a smartphone, internet or phone credit, literacy, and basic technological knowhow.

Advocates have tried to impart new skills to migrants and refugees in shelters across the U.S.-Mexico border. Their assistance can be as basic as taking a photo of the person trying to register on the app and uploading it. Others need translation help – CBP One is only available in English, Spanish, and Haitian Creole.

The simplicity of some of the questions and roadblocks underscores just how complicated relying on a digital app for such an at-risk and transient population can be. “It’s supposed to protect the most vulnerable, but for many it’s inaccessible,” says Lindsay Toczylowski, executive director of the Immigrant Defenders Law Center.

Seeking asylum in the US? Make sure your cellphone is charged.

The day has just begun in the historic center of Ciudad Juárez, at Mexico’s northern border. Among the food vendors and border-bridge traffic, pedestrians are angling their cell phones outward, then upward, then back down again. Some snap selfies; others grumble about their faulty connection.

But this is not merely a slice of life in 2023 – a society glued to its digital devices. These are migrants attempting to take the first step, as they do every day at 9 a.m. sharp, to claim humanitarian protection in the United States.

Welcome to America’s latest tech initiative: asylum via app.

Since Jan. 12, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has required individuals seeking to enter the U.S. under exemptions to Title 42 – a temporary pandemic-era law that has been used to expel asylum-seekers and migrants over the past three years – to use the new CBP One mobile application.

The app accepts appointments from Mexico for just several minutes each morning, and while the fortunate have scored spots with it quickly, it has put others at the whim of tech, its glitches and all. Widening the digital divide, the app demands asylum-seekers have access to a smartphone, internet or phone credit, literacy, and basic technological know-how. Critics say that doesn’t jibe with the reality for many here hoping to gain humanitarian protection in the U.S. And it adds more inequality and arbitrariness into a process that for most users is the most defining step of their lives.

David, a law student in his early 20s who says he fled political repression in Nicaragua last November, is unequivocal: “I hate the app,” he says, sprawled out under a lone tree on the Mexican bank of the Rio Grande on a recent April morning.

The ‘best country?’

With Title 42 expected to end this week, the app will persist – but there might be some relief. CBP announced changes on Friday that will go into effect May 10, including increasing the number of appointments available, allowing more time to complete the request process, and giving priority to people based on when they registered on the app. These changes cannot come fast enough for those like David.

Frustrated after two months of trying to get an appointment through the app, which constantly crashed right before confirming a time or simply wouldn’t load, he and two friends were considering climbing the U.S. border fence and turning themselves in to authorities for a chance to ask for asylum. One of them, Alex from Honduras, followed through, and says he was shot with rubber bullets and beaten with a firearm by Mexican officials. He lifts his sweatshirt to display his wounds. The young men say they fear Mexican police, broad cartel presence, and their growing vulnerability as the cash they set out with dwindles.

The U.S. “is supposedly the best country in the world, and they can’t make an app that works?” David asks. “I can connect to everything – music, social media, the news – but when I open CBP One it’s always loading? No. This was designed to fail.”

Across town in Ciudad Juárez in a migrant shelter, Keisy Plaza used to share those sentiments. That is, until she clinched an appointment for her family of four the week prior. The Venezuelan mother does a reenactment – screaming and clutching her face – of what it was like to finally see the little confirmation message noting her appointment for early May.

“I felt desperate before getting this appointment,” Ms. Plaza says.

At the Espacio Migrante shelter in Tijuana, the Immigrant Defenders Law Center (ImmDef) tried to impart new skills to the roughly 100 migrants and refugees in crowded rows. Know-your-rights and CBP One trainings and presentations are increasingly common at shelters across Mexico. But ensuring migrants have the most up-to-date information can feel like a game of chicken. “Just on our way down here today [President] Biden announced upcoming policy changes,” says Lindsay Toczylowski, executive director of ImmDef.

After the presentation, attendees are invited to stay for one-on-one meetings with 10 visiting U.S. lawyers. Their assistance can be as basic as taking a photo of the person trying to register on the app and uploading it. Others need translation help – CBP One is only available in English, Spanish, and Haitian Creole. The simplicity of some of the questions and roadblocks underscores just how complicated relying on a digital app for such an at-risk and transient population can be.

“It’s supposed to protect the most vulnerable, but for many it’s inaccessible,” says Ms. Toczylowski.

According to the latest CBP data, between January and March more than 74,000 people successfully scheduled appointments through the CPB One app, largely citizens from Mexico, Venezuela, and Haiti. U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas announced April 28 that while more appointments will be made available after May 11, when Title 42 expires, the consequences for approaching the border without using the app will become harsher, including expedited removal proceedings.

An orderly line

At another shelter on the outskirts of Tijuana, Belkis Rivera says when it comes to CBP One she simply feels exhausted. Her family fled Honduras a year ago after she says her husband and youngest daughter were beaten by local gangs for missing an extortion payment.

Before CBP One was launched, they’d spent 5 months on an informal list of asylum-seekers kept by the shelter, which would hear from U.S. officials each week how many people from the list could get an exception to present themselves at the border. Had the app not been launched, her family would have been up for their chance to speak with border agents next month. Now, she fears it could be another year.

“We are so grateful to be here,” she says of the shelter that’s provided food, beds, two church services a week, and activities for her children. “But I’m sleeping in a room with 800 people. I’m exhausted,” she says. “Then someone who just arrived will get an appointment that same week,” she trails off.

“I’m happy for them. But I understand why some people are quitting the app to cross illegally,” she says.

“Will we ever get our chance?”

End of gas stoves? New York is first to ban gas in new buildings.

Does responsibility lie in moving quickly to scale down emissions of natural gas, or in being cautious about the effects of energy mandates on consumers and the electric grid?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Hillary Chura Contributor

New York is the first state to begin banning natural gas in most new buildings – a move praised as pathbreaking by climate advocates but criticized by opponents as overbearing.

It’s part of a larger state plan to reach net-zero energy emissions by 2050.

Most Empire State residents support the goal of lowering greenhouse gas emissions, but gas-range aficionados don’t want to give up their open flame. Critics say this plan will be costly to consumers, could overtax the state’s energy grid, and doesn’t account for cold winters.

Natural gas burns cleaner than fossil fuels like coal and oil, but it can pollute just as much, depending on how much methane leaks from production to delivery.

Instead, the new law calls for heating buildings and their water with energy-efficient electric heat pumps. Supporters say the heat pumps are effective, save consumers money over time, and draw their electricity from a grid increasingly powered by renewable energy sources.

The policy’s rollout here will be closely watched. Already a number of cities have banned gas in new construction. While some Republican-controlled states have laws preventing local gas bans, Washington state has a ban imposed by its unelected Building Code Council.

End of gas stoves? New York is first to ban gas in new buildings.

New York is the first state to begin banning natural gas in most new buildings – a move praised as pathbreaking by climate advocates but criticized by opponents as overbearing.

It’s part of a larger state plan to reach net-zero energy emissions by 2050. Supporters hope other states will join.

Yet, while most Empire State residents agree that lowering greenhouse gas emissions is the right move, gas-range aficionados don’t want to give up their open flame. Critics say this plan will cost struggling consumers too much, could overtax the state’s energy grid, and doesn’t account for the severity of New York’s numbingly cold winters.

Natural gas is used widely to generate electricity here and around the country. It burns cleaner than fossil fuels like coal and oil, but can pollute just as much as coal, depending on how much methane leaks from production to delivery. The new law calls for energy-efficient heat pumps instead.

In 2021, slightly more than half of New York’s electricity came from clean sources like nuclear and renewables such wind, solar, hydro, and geothermal pumps, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. The state’s goal is 70% emissions-free electricity production by 2030 and 100% by 2040. In addition to helping solve climate change, advocates say boosting green energy will create jobs, improve indoor and outdoor air quality, and lower utility costs.

The policy’s rollout here will be closely watched. Already a number of cities from San Francisco to New York City have banned gas in new construction. While some Republican-controlled states have laws preventing local gas bans, Washington state has a ban imposed by its unelected Building Code Council.

How will the law work?

By 2026, most new buildings under seven stories will have to use electric heat pumps for controlling air temperatures and for hot water. Larger buildings will have to comply by 2029. Some businesses that require extreme high heat to operate are exempt. The law does not apply to existing buildings.

Buildings produce more greenhouse gases than any other category in New York – 32% of emissions versus 29% for transportation – according to the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation.

Will it lower emissions?

Initially, no. But it keeps new buildings from raising them. Bigger savings will come once existing buildings are retrofitted and the sale of gas appliances is banned, all part of the state’s net-zero-by-2050 plan. Those details have not been ironed out and could be derailed if, say, future governors have different priorities.

What will it mean for consumers?

Supporters say electric heat pumps are effective and save consumers money over time. Critics warn of unintended consequences and call for a more measured approach.

“The ban on natural gas hookups in new buildings will drive up housing costs and utility bills for consumers. Without greater detail and analysis [about the grid], this one size fits all plan is unrealistic, unaffordable and unreliable,” says Republican state Sen. Patrick Gallivan, by email.

It used to be that heat pumps were no match for eye-watering cold, but they have improved greatly over the past decade and are quite efficient, says Robert Howarth, an Earth systems scientist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and one of 22 members on the state’s Climate Action Council tasked with developing the state’s net-zero plan.

Still, plenty of builders remain dubious.

Heat pumps tend to be more efficient and cheaper to run than natural gas furnaces. In new homes, this means that electrifying things can make a lot of sense. But with older homes, it’s a bit trickier, in large part because of the upfront costs to renovate, says Melissa Lott, director of research at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

Can the grid handle more demand?

Supply will become a problem if the electric grid and alternative energy sources aren’t improved and expanded, according to the New York Independent System Operator, which manages the flow of electricity across the grid. The state’s energy cushion could narrow beginning in 2025 as some generators are deactivated and demand grows, says Kevin Lanahan, the company’s vice president of external affairs and corporate communications.

The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority says the state has enough projects in the pipeline to reach 2030 and 2040 goals.

That’s not sufficiently concrete for some.

“Sure, down the road, technology will catch up and move forward with electric, but we want proof [that it’s happening on pace]. And they can’t answer that,” says Michael Fazio, executive vice president of the New York State Builders Association, which works with residential builders.

While grid capacity is concerning, some big developers started shifting from gas homes to all-electric ones a few years ago in anticipation that the state and utilities will work out supply, says Michael Ohlhausen, managing director of architecture at The Hudson Companies, a developer of multifamily apartment buildings in New York City and Westchester County, just north of the city.

Low-rise residential builders, like Mr. Fazio’s members, are on board with the move toward zero emissions, but worry that buyers won’t want all-electric homes if reasonable gas-fueled ones exist – making it hard for his members to survive.

Are there obstacles to implementation?

In addition to the need to make sure the grid and alternative energy supplies are robust, there could be legal challenges.

This spring, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in California overturned a Berkeley, California, law that had the same goal as New York state’s but was implemented differently. Amy Turner, senior fellow at Columbia’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, says she does not expect New York’s 2nd Circuit Court to do the same, but the natural gas industry has deep pockets to bring suit.

How does the public feel about it?

Far more New Yorkers believe climate change is a serious problem than don’t believe, according to a February poll by Siena College and the natural gas-aligned New Yorkers for Affordable Energy – 77% compared with just 22%. But climate change is far less important than day-to-day issues – like cost of living, housing affordability, and crime.

“People are thoughtfully ambivalent,” says Donald Levy, director of the Siena College Research Institute, which conducted the survey. “Most are willing to pay something to help with climate mitigation – but not much. They like the state’s aggressive goals, but there’s a sense that ‘if other states aren’t doing this, why should I?’”

In Pictures

In Senegal, the kora ‘brings me closer to God’

By embracing the kora, a local instrument, the Roman Catholic monks at Keur Moussa changed the way they worshipped – and introduced generations of new listeners to a centuries-old sound.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By Guy Peterson Contributor

-

Nick Roll Contributor

In the countryside some 30 miles outside Dakar, Senegal’s bustling capital, melodic twangs rise up the white walls of Keur Moussa monastery. They slip out through the latticework near the roof – lyrical melodies filled out by warm bass notes.

Koras – the harplike instruments the monks are playing inside – have been used across centuries, by everyone from West Africa’s pre-colonial singing historians to modern jazz and rock groups today.

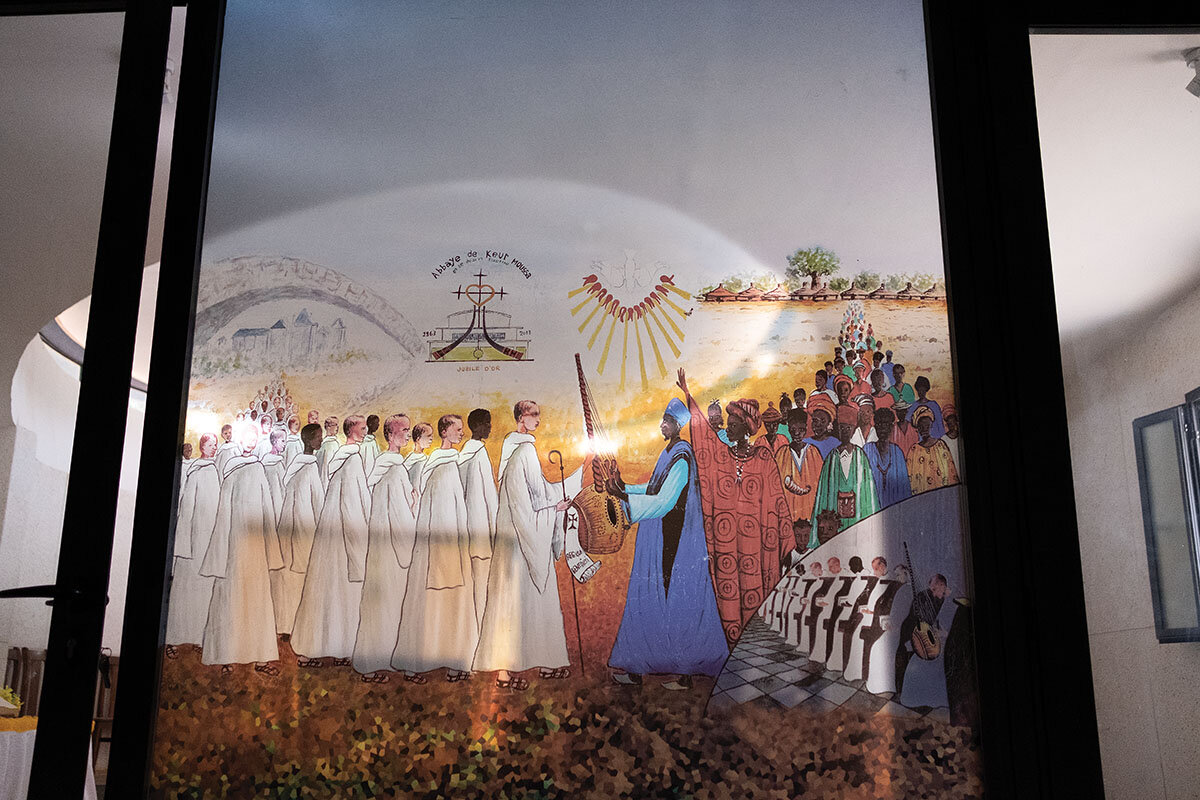

But the kora was little known in Senegal outside of the minority Mandinka ethnic group before the monks of Keur Moussa Abbey started using it. In the 1960s, they embraced the instrument, morphing their Gregorian chants into songlike prayers accompanied by the kora.

The kora fundamentally changed the monks’ worship. But the monks also transformed the kora, modernizing its tuning pegs and spreading its international popularity.

“It was work – it didn’t just happen,” says Brother Marie Firmin Wade, who builds koras at the monastery workshop.

Congregant Hélène Ngom, walking out of a recent Sunday mass, says, “It’s an instrument that when you listen to it, it takes you. When I listen to the kora, I rise, divinely. It brings me closer to God.”

In Senegal, the kora ‘brings me closer to God’

Morning sun filters into the monastery church as the melodic twang of two harplike instruments – known as koras – fills the air, combining with the voices of two dozen singing monks. The music rises up the white walls and out through the latticework near the roof – lyrical, looping melodies filled out by warm bass notes.

The kora has been used across centuries by everyone from West Africa’s pre-colonial singing historians to modern jazz and rock groups today.

But the kora was little known in Senegal outside of the minority Mandinka ethnic group before the monks of Keur Moussa Abbey started using it. In the 1960s, when the Roman Catholic Church was modernizing and just after Senegal had shaken off French colonial rule, the monks of Keur Moussa embraced the instrument, morphing their Gregorian chants into songlike prayers accompanied by the kora.

“It was work – it didn’t just happen,” says Brother Marie Firmin Wade, who builds koras. “That’s what has created all the liturgical richness of Keur Moussa. Because Keur Moussa has taken a bit from everywhere.”

Congregant Hélène Ngom, walking out of a recent Sunday mass, says, “It’s an instrument that when you listen to it, it takes you. When I listen to the kora, I rise, divinely. It brings me closer to God.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

For two of the world’s pariahs, more honey than vinegar

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For the second time in less than a year, a country that is a global pariah has reemerged from the shadows. Arab leaders yesterday accepted Syrian President Bashar al-Assad back into their regional alliance more than a decade after shunning him for alleged war crimes. The decision by the Arab League follows a similar thaw for Venezuela. Latin American leaders and the Biden administration have begun cautiously drawing President Nicolás Maduro into the international fold after years of isolation.

These moves toward engagement with Syria and Venezuela bring up challenging questions on how to help people living under repressive regimes achieve their preferred style of governance. Yet at another level, these two cases reflect how countries in the Middle East and Latin America are seeking to reset the terms of governance at a time when great-power rivalries are exacerbating problems in poorer countries.

The world is trying a new strategy with Syria and Venezuela: patient confidence-building. So far punitive coercion has not worked.

For two of the world’s pariahs, more honey than vinegar

For the second time in less than a year, a country that is a global pariah has reemerged from the shadows. Arab leaders yesterday accepted Syrian President Bashar al-Assad back into their regional alliance more than a decade after shunning him for alleged war crimes – including the use of chemical weapons – against his own people.

The decision by the Arab League follows a similar thaw for Venezuela. Latin American leaders and the Biden administration have begun cautiously drawing President Nicolás Maduro into the international fold after years of isolation.

These moves toward engagement with Syria and Venezuela bring up challenging questions on how to help people living under repressive regimes achieve their preferred style of governance. As the Gulf nation of Qatar argued yesterday – against the league’s decision – readmitting Mr. Assad should first require “a change on the ground that achieves the aspirations of the Syrian people.”

Yet at another level, these two cases reflect how countries in the Middle East and Latin America are seeking to reset the terms of governance at a time when great-power rivalries are exacerbating problems in poorer countries.

“Securing a sustainable place in the emerging multipolar world order is a matter of survival for Arab states,” wrote Malik al-Abdeh, a Syria expert, in a recent essay for the Atlantic Council. The Middle East, he argues, offers an opportunity to rethink influence “as a competition for the best ideas and offers that can create new qualities of alliances [that] ... encompass a large degree of Western values and norms.”

The crises in Syria and Venezuela have unfolded in parallel time frames. Syria descended into civil war during the Arab uprisings of 2011. Within a year, Mr. Assad’s regional peers ostracized the Syrian president amid mounting evidence of gross human rights violations. The conflict drew in five foreign militaries and displaced 6.8 million people. Some 90% of Syrians live below the poverty line.

Venezuela saw economic collapse amid falling oil prices in 2016. Half of Venezuelans live in poverty. More than 7 million have fled. Mr. Maduro has maintained his grip on power through rampant corruption, patronage networks, and crackdowns on dissent.

To force both leaders from power, the United States and other Western countries have applied increasingly stiff economic sanctions. Yet while U.S. administrations came and went, Mr. Assad and Mr. Maduro stayed. In recent years, Syria’s neighbors have cautiously sought economic ties with it. After Russia invaded Ukraine, the Biden administration, seeking new sources of oil, offered an exchange: a modest resumption of oil purchases if Mr. Maduro engaged in talks to restore democracy.

Venezuela has gained a local champion. Colombia’s new president, Gustavo Petro, has made engaging his neighbor a key part of his pursuit of peace and stability. Democracy in Venezuela must “evolve with history,” he says.

The world is trying a new strategy with Syria and Venezuela: patient confidence-building. So far punitive coercion has not worked.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘Z’ is for ‘zeal’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Liz Butterfield Wallingford

Each of us can play a part in nurturing the kind of zeal that heals: a wholehearted desire to live the pure goodness that God expresses in all His children.

‘Z’ is for ‘zeal’

Nearly every year I was in elementary school, we were tasked with composing an acrostic based on our first name. This involved writing our name vertically down the page, and then using each letter as the beginning of a word that we felt described us.

In my case – “Elizabeth” – the “z” always posed an interesting challenge, especially given my determination to avoid reusing words from year to year. “Zany” made an appearance, the only “z” word I could think of in that moment. One year I chose “zoologist” to reflect my love of animals. Another time, the idea “‘Z’ is for ‘zeal’!” came to mind. (That year we were required to use adjectives, so I went with “zealous,” reasoning that there were, after all, things I was enthusiastic about.)

In the years since, I’ve come to really appreciate the concept of zeal. Not the fanatic, zealot sense of it, but the kind of zeal that is pure and invigorating and that blesses us and those around us.

The Bible talks about being “zealous of good works” (Titus 2:14), or as the J.B. Phillips New Testament puts it, having “our hearts set upon living a life that is good.” It’s a theme that Mary Baker Eddy, a follower of Jesus and the discoverer of Christian Science, echoes in her writings, referring to “honest, wise zeal,” for example (“The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” p. 259).

In fact, “zeal” is included in the Glossary of Mrs. Eddy’s primary work, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” which includes spiritual definitions of biblical terms. Its two-part definition of “zeal” offers a clear distinction between an inspired, beneficial zeal and untempered fervor. The first part is “The reflected animation of Life, Truth, and Love.” The second is the counterfeit of that uplifted sense: “Blind enthusiasm; mortal will” (p. 599).

That first definition packs a lot of punch. “Life,” “Truth,” and “Love” are capitalized because they’re being used as synonyms for God. So true zeal is a quality of God. It’s incorruptible and doesn’t include zealotry or fanaticism, because God is All and infinitely good; all that He imparts is uplifting, unadulterated, loving, and all-blessing.

What’s more, we can all identify with and nurture this kind of zeal – whether or not we have a “z” in our name. Our real nature is not defined by mortal attributes at all. It’s defined by God, who created us as the expression of His own nature – the reflection of divine Spirit, Life, Truth, Love. The vivacity of divine Life, the integrity of divine Truth, and the tenderness and grace of divine Love are inextricably part of our identity.

An honest desire to live these ideas with all our heart empowers us to make a real difference for good, whether in small ways or large. This happens not through willfulness, “blind enthusiasm,” or pushiness, but through humble yielding to Christ, the divine message that opens our eyes to the spiritual reality of what God is and, therefore, what we are.

When we let Christ animate our thoughts and actions, we’re expressing zeal. The outcome is that we’re more alert to unhelpful modes of thought that would impede progress and healing – the mortal counterfeits of genuine zeal – and more equipped to neutralize them, letting pure qualities sourced in divine Life, Truth, and Love shine through us. Then harmony and productivity begin to more consistently characterize our interactions and endeavors.

It’s not always easy, especially when we feel passionate about something. I’ve certainly been there. But I’ve also found that when my motivation, first and foremost, is to actively reflect Life, Truth, and Love – rather than crusade for a personal agenda, however well-intentioned – the outcome always blesses, even if in different ways from what I’d initially envisioned.

Day by day, moment by moment, each of us can nurture a humble, wholehearted, dynamic yearning to live our true nature as the reflection of God, good – and to support others in this, too. That’s the zeal that uplifts, inspires, and even heals.

Viewfinder

Finding support

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. Please come back tomorrow, when we’ll have a story on Capri Glee!, an amateur choir in Minneapolis that fosters opportunities to connect – and spread joy.