- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 12 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Beyond the fortress of books

Jackie Valley

Jackie Valley

I grew up in the era of Toys R Us, when Geoffrey the Giraffe beckoned kids from across the parking lot or through the television screen to a wonderland that seemed to offer every toy imaginable.

Yet, other than a vague recollection of toy-filled aisles, I have no specific memory attached to that store. What I do remember are regular trips to the public library in Merrillville, Indiana, with my mom and twin sister.

We’d enter the book fortress and make a beeline for the children’s floor upstairs. First stop: story hour. But the real joy – and first taste of independence – came afterward when our mom would let us wander the aisles choosing new books to check out. It’s how I met the venerable Clifford, Arthur, and Berenstain Bears. (If you sense an animal theme, I’m guilty as charged.)

The library visits sparked wonder and imagination – and were only made possible by a parent who could take us. Not every child is so fortunate, especially nowadays.

The librarians I met at the Missouri River Regional Library in Jefferson City while reporting today’s cover story are keenly aware of how difficult it can be for some families to access their stacks. So they have several initiatives designed to extend the library’s reach, including a brightly colored bus dubbed the “Bookmobile” that makes frequent excursions to places such as schools and malls.

The library system maintains lockers at the local mall, allowing cardholders to select items online and pick them up in what’s perhaps a more convenient location.

A third innovation borrows from subscription programs that pair personal stylists with clothing buyers. With “Book Box,” readers can explore a personalized selection of titles packed just for them – think Stitch Fix for books.

These strategies bring the gifts of the library to people who may lack transportation or time to wander the aisles themselves. For children in particular, an interest in reading could blossom into a love for reading, opening incalculable future doors.

And some of those doors might very well be attached to the brick-and-mortar library itself.

Patty Eastin, a Jefferson City resident who stopped by the library, summed it up this way: “I’ve always felt at home in a library.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Between the stacks: A day in the life of a library

Despite legislators’ threats to defund libraries, this busy one looks toward the future, with plans to expand its embrace of the community.

-

Alfredo Sosa Staff photographer

“The really amazing thing about libraries – and this is true around the world about public libraries – [is that] anybody can go in them, and you’re not expected to spend money,” says Emily Knox, an associate professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

But in America, this institution has come under siege with efforts to ban books and, in some cases, restrict or end public funding for libraries.

“It’s discouraging, but I am undaunted by it,” says Claudia Young, director of the Missouri River Regional Library system in Jefferson City, Missouri. “I believe so much – I’m going to get tearful,” she says, pausing for a moment. “I believe so much in what we’re doing that I don’t let it get me down.”

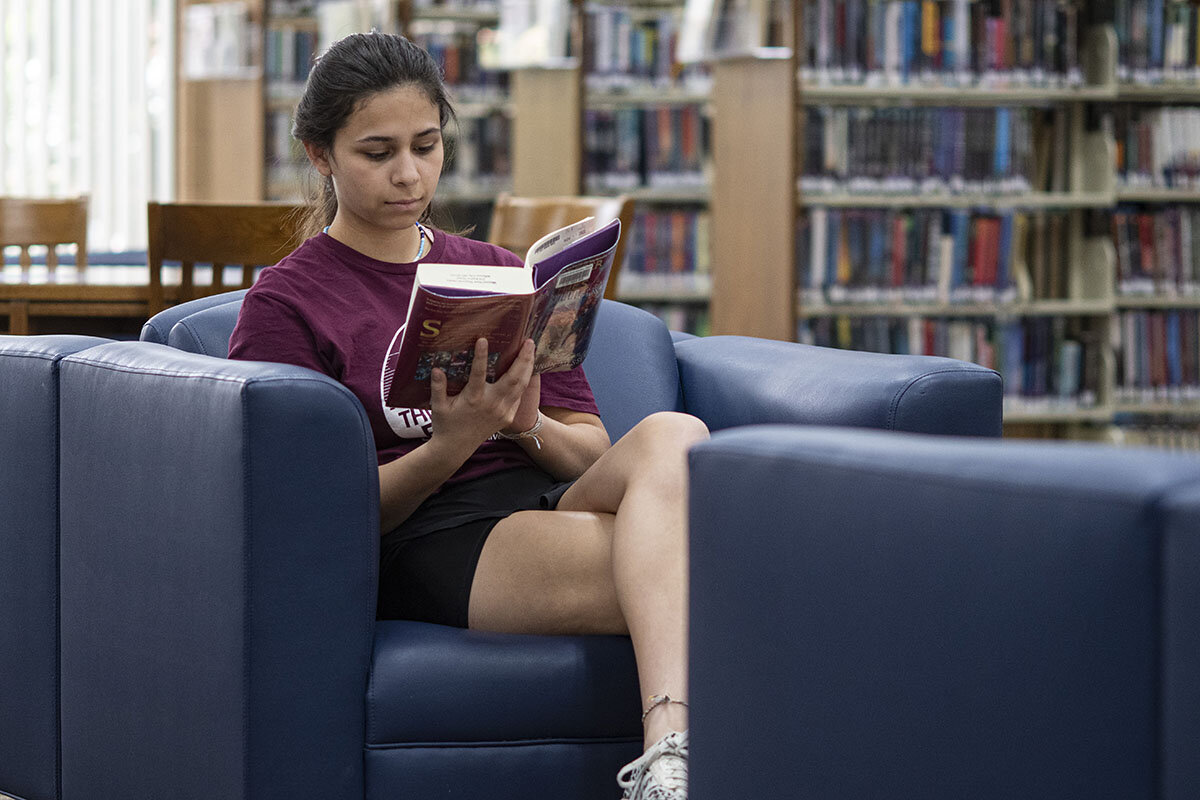

Nor do library patrons, it appears. Earlier in the morning, children at this branch joined in singing during a story hour, and as afternoon descends, new visitors arrive. A mother helps her daughter with schoolwork. Teenagers browse aisles and lounge in an upstairs room dedicated to them. A man snoozes in a chair on the first floor. Even Jay Ashcroft, Missouri secretary of state, wanders in while chatting in hushed tones on a cellphone.

As long as people aren’t making a disturbance or violating a library policy, Ms. Young says, all are welcome to enjoy its quiet solace, access resources and services, or connect with others.

Between the stacks: A day in the life of a library

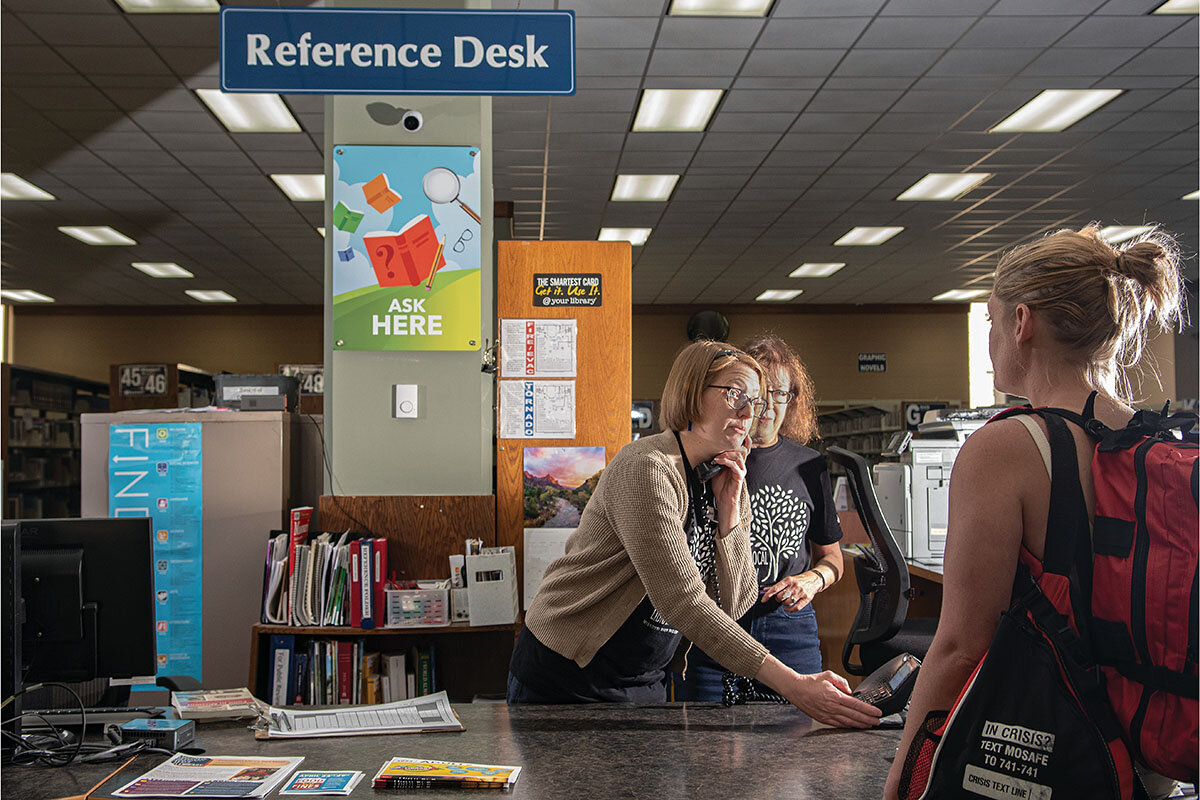

Del Prenger enters the main branch of the Missouri River Regional Library seeking a solution.

Weeks earlier, a 9-year-old relative had mailed her a brightly colored self-portrait. The artwork came with a request: Take the paper cutout version of him on adventures and report back. It’s a popular elementary school ritual inspired by the children’s book “Flat Stanley,” whose eponymous character embarks on thrilling experiences after being pancaked by a bulletin board.

Ms. Prenger accepted her mission. She photographed the boy’s self-portrait joining her as she played dominoes with friends, visited a relative in a nursing home, and met an Elvis impersonator in Branson. Next, she typed a letter detailing his travels and then – much to her dismay – hit a snag. It wouldn’t print.

“I was so frustrated,” she says. “I said, ‘Where in the world can I go?’ And I thought, I’m going to run up to the library.”

So here she is, laptop and photos in hand, shortly after 5:30 p.m. on a Tuesday. The reference librarian listens to her story and dives into problem-solving mode. Soon, her letter emerges from the printer.

“The really amazing thing about libraries – and this is true around the world about public libraries – [is that] anybody can go in them, and you’re not expected to spend money,” says Emily Knox, an associate professor in the School of Information Sciences at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

But in America this institution has come under siege with efforts to ban books and, in some cases, restrict or end public funding for libraries.

Last year marked the largest number of censorship attempts since the American Library Association began tracking that information more than two decades ago. Reported book challenges increased 38% from 2021 to 2022, landing at 2,571 unique titles.

And in the Missouri State Capitol – a mere half-mile from the public library in downtown Jefferson City – lawmakers in the House sent a bill to the Senate that stripped funding from public libraries.

But the all-day hum of activity inside this two-story, Brutalist-style library defies what some perceive as an attempt by a faction of conservatives to silence certain perspectives.

Libraries help job seekers, small-business owners, students preparing for tests, parents who want to promote early literacy, and people who need a respite from hot or cold weather, among countless other functions. They’re also one of the first brick-and-mortar institutions that open their doors and provide assistance when natural disasters strike, notes Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom.

“All that goes away when you say, ‘Let’s defund the libraries because we don’t like a few books on the shelves,’” she says. “It really is the essence of elevating politics over the needs of communities.”

Centuries ago, when Benjamin Franklin founded the member-supported Library Company of Philadelphia in 1731, it wasn’t the technological wonderland libraries have become today. But the nation’s first lending library did let members borrow science equipment, such as telescopes and air pumps, says Michael Barsanti, its executive director. In that sense, it was never solely about books.

Libraries grew and evolved along with America. By 1848, the Boston Public Library opened its doors, ushering in an era of free library service in the United States. Now, more than 9,000 public libraries exist nationwide – and the services they offer have multiplied well beyond printed literature.

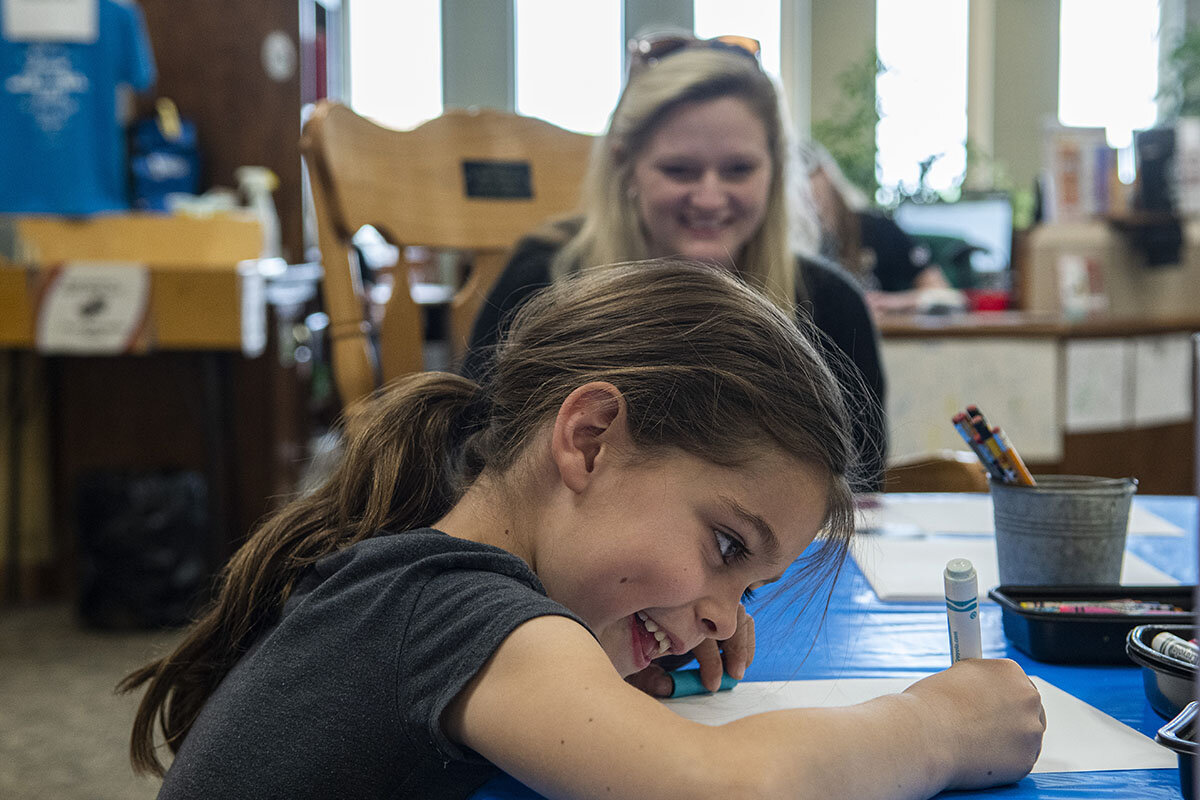

Educational tablets, fishing poles, and tackle boxes are available for checkout here in the children’s section. And last year, the library started working with local agencies to connect community members with help for energy bills, health care, food, and financial matters. The library – like its peers in many other cities – sits on the bus line and is centrally located.

“When they’re able to come here and kind of hit everything at once, it just removes a lot of barriers,” says Natalie Newville, the library’s assistant director of marketing and development.

But books matter, too. In a bid to engage more readers, the library offers a free subscription service dubbed “Book Box.” Children, teens, and adults fill out forms identifying their book preferences and personal interests. Then library selectors do their best to provide matches.

The element of surprise attached to the program has proved popular. “Our circulation numbers have gone up with it,” Ms. Newville says.

That’s not the only growth the library is working on.

Claudia Young bows out of a conversation and heads toward a wooden podium set up near the library’s front doors. After 27 years working in this library – now as its director – Ms. Young knows many patrons by name. And the person she is about to honor happens to be particularly well known in Jefferson City.

“I’d like to get everyone’s attention,” she says. “We’re going to start the ceremony now for ambassador of the year.”

To her right stands Carrie Tergin, who just a week earlier finished her eight-year run as the capital city’s mayor. She’s receiving the annual ambassador award, given during National Library Week to someone who understands what the library does for the community and shares that message broadly. Ms. Young ticks off a list of the former mayor’s supportive acts – everything from attending events to plugging the library in speeches and on social media.

But it will take more than a few ambassadors to steer the library in the direction envisioned by its board and staff. The Missouri River Regional Library is asking voters to approve an increase to the operating levy on the August ballot. If approved, it would amount to an average 2.5% property tax increase for most households.

The extra money would go toward expanding and renovating the main branch in Jefferson City – which swells each winter and spring as lobbyists and lawmakers converge for the legislative session – and providing more services for the surrounding, mostly rural Cole County. The area it serves counts nearly 77,000 residents.

Architectural renderings stationed around the library depict a bright and airy building with a new third floor and outdoor space on a second-floor rooftop. Inside, library officials say, the modernized building would feature shorter, more accessible bookshelves, new restrooms, dedicated space for job skills development, study rooms, and makerspaces.

If voters give the tax increase a green light, the additional yearly cost per $100,000 of home value would be $28.50.

“The time is right” for an expansion, Ms. Tergin says while accepting her award. “We’re going to make it even better.”

Her enthusiasm comes amid a backdrop of cultural and political turmoil. Last year, legislation surfaced in 12 states that would permit criminal prosecution of librarians and educators for distributing certain materials to minors, according to the American Library Association, which has condemned the efforts.

In Missouri, the strife stretches back to August when Republican Gov. Mike Parson signed sex-trafficking legislation (Senate Bill 775) into law. It included an amendment that puts school librarians and educators at risk of criminal prosecution if they provide “explicit sexual material” to a student. School librarians, afraid of potentially breaking a law, preemptively began removing books they thought might fall under that broad description.

Then Missouri’s secretary of state, Jay Ashcroft, a Republican running for governor, proposed a rule that tied state funding for public libraries to a number of requirements, including that money cannot be used to purchase materials that “appeal to the prurient interest of any minor.” It also required libraries to adopt policies providing parental consent for materials checked out by children and teens.

The Missouri Library Association fired back, calling the proposed rule a “solution in search of a problem.” The association also noted that a few of the requirements are already best practices within libraries.

The proposed rule, which drew 20,000 public comments, is going into effect with a few modifications. In response to a concern that “prurient” is too vague, for example, the terms “child pornography,” “obscene,” and “pornographic for minors” are being used instead.

By late February, the American Civil Liberties Union of Missouri filed a lawsuit on behalf of two organizations – the Missouri Library Association and the Missouri Association of School Librarians – challenging the constitutionality of Senate Bill 775.

A month later, the Missouri House Budget Committee removed $4.5 million in state aid to local libraries from the budget bill. Critics blasted it as a retaliatory move that would hurt rural libraries the most. Ultimately, the Legislature passed a budget plan that restored state funding for public libraries.

“It’s discouraging, but I am undaunted by it. I believe so much – I’m going to get tearful,” Ms. Young says, pausing for a moment. “I believe so much in what we’re doing that I don’t let it get me down.”

Ms. Young grew up in a small Illinois town that couldn’t support its own library. A bibliophile at heart, she calls this her dream job. The shelves of books, the room full of computers, the aisle of video games, the 3D printer, and even the cozy chairs – these are the tangible objects that draw patrons to the library. Together they form a social fabric, she says, that strengthens individuals and the community at large.

“People can become the best version of themselves by using the library, whether that’s to learn a new skill or have access to information they need,” she says.

Jefferson City’s name is an ode to Thomas Jefferson, a Founding Father and the nation’s third president who famously wrote a letter declaring, “I cannot live without books.”

The growing city, however, didn’t receive its own public library until the turn of the 20th century. A grant from philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, who contributed to the establishment of nearly 1,700 libraries between 1886 and 1919, helped fund Jefferson City’s first public library, which opened in 1902. Today, the Missouri River Regional Library’s main branch sits next to that original building.

Last year, 158,520 visitors entered the library, and 445,920 materials were checked out. Recent popular items include Prince Harry’s memoir, “Spare”; the movies “A Man Called Otto” and “Everything Everywhere All at Once”; and the novels “Losing Hope” by Colleen Hoover, “Identity” by Nora Roberts, and “Happy Place” by Emily Henry.

But at 10:30 a.m. on this day, those stats take a backseat to preschool story time. Three toddlers and a handful of adults gather in an upstairs meeting room. To the tune of “Wheels on the Bus,” Donna Loehner, a youth services programming assistant, reads aloud a picture book called “The Library Doors.”

The words mimic what librarians see day in and day out, and as the children catch on, they add their tiny voices to the mix:

The library doors swing

OPEN AND SHUT,

OPEN AND SHUT,

OPEN AND SHUT.

The library doors swing

OPEN AND SHUT

All through the day!

Grace Shaw and her 2-year-old son, Blake, are among the attendees. Ms. Shaw considers the library a safe, positive place where her children can be imaginative and learn about other people and the world around them. As Blake scans a nearby shelf for books about dinosaurs, Ms. Shaw says her family and many of their friends fall on the more conservative side of the political spectrum, but they’re big supporters of the library.

“We monitor what our kids read and watch and stuff and just also talk with them through things they read and things that they see in general,” she says.

Downstairs, retired accountant Mark Rodabaugh has finished his library to-do list for the day – printing a schedule and looking up a book recommended by a friend. Trips to the YMCA and the library make up the bulk of his weekly routine.

His take on state library funding being in jeopardy: “It’s a horrible thing.”

Mr. Rodabaugh shakes his head at the mention of culture wars triggering attempts to pull certain books from shelves. He says one person or group of people shouldn’t be dictating what everyone else can read.

Books written by or about people of color and members of the LGBTQ+ community made up the “vast majority” of items challenged or banned last year in libraries across the nation, according to the American Library Association. Forty-eight percent of the challenges occurred in public libraries, and another 41% involved school libraries.

“I have great faith in the library systems that have professional people making these decisions on books,” Mr. Rodabaugh says. “And I want that to continue.”

In the library’s basement, beyond rows of computers in the public business center, staff work behind the scenes taking care of daily operations. An aspect of that mission: selecting materials.

Library staff order new books, video games, and DVDs, among other items, from January through October, Ms. Young says. They use publications such as Library Journal and Publishers Weekly to help them select titles, while also paying attention to bestseller lists and stocking up on the eternally popular romance and Western genres.

The library added roughly 12,500 new items in 2022 and withdrew another 19,618 based on their condition and checkout history. Does every patron like or agree with the views presented in all the books and movies? Certainly not, Ms. Young says. The goal, as stated in the library’s collection development policy, is to provide a “diverse and balanced collection of materials.”

So far this year, the library has received one challenge concerning a children’s picture book, Ms. Young says. Prior to that, the most recent challenge occurred in 2021 – also involving a children’s picture book that the petitioner perceived as promoting an LGBTQ+ agenda. In such cases, the person or group initiating the challenge fills out a form requesting reconsideration, which jump-starts a review process involving the selector of that particular material and the collection development manager. If the patron disagrees with the decision, he or she can request to speak with the library’s director or, ultimately, board of trustees.

“Materials are evaluated as complete works and not on the basis of a particular passage,” the library policy states. “A work will not be excluded from the library’s collection solely because it represents a particular aspect of life, because of frankness of expression, or because it is controversial.”

Misinformation and disinformation have led to books about sexuality and reproductive health being “described in the worst terms,” says Ms. Caldwell-Stone, of the American Library Association. She worries about what may happen if libraries remain under attack.

“Without libraries, you can’t pull yourself up by your bootstraps. Without libraries, you may not be able to access government services, scholarship applications,” she says. “We need to just remember that libraries are really essential to the functioning of our economy, our democracy, our very lives.”

It’s a statement that Ben Franklin very likely would have endorsed. Dr. Barsanti suspects that the famous inventor and statesman, who tried to avoid making blanket statements, would have concluded that “controlling books is doomed to fail.”

And as technology and its effect on daily life continue to evolve, particularly with the growing use of artificial intelligence, Dr. Barsanti predicts the role of librarians will become even more important.

“What was already a very wild information environment is just going to get crazier,” he says. “And what we will increasingly need are communities that will help us to evaluate the quality of the information we’re getting.”

As afternoon descends on Jefferson City, new visitors arrive. A mother helps her daughter with schoolwork. Teenagers browse aisles and lounge in an upstairs room dedicated to them. A man snoozes in a chair on the first floor. Even Mr. Ashcroft, the secretary of state, wanders in while chatting in hushed tones on a cellphone.

As long as people aren’t making a disturbance or violating a library policy, Ms. Young says, all are welcome to enjoy its quiet solace, access resources and services, or connect with others.

As the clock ticks toward 8 p.m. – when the library will close – 18-year-old Madalynn Sanford is making a flower lantern in a crafting class.

When her family moved to Missouri from Arizona, she began attending the library’s teen programming. She made friends here, learned some sewing techniques, and recently transitioned to the adult programs.

“It’s definitely a place where I think about a community,” she says.

At the same time, Ms. Young, the library director, is several miles away at a Lions Club meeting making a pitch she plans to repeat 24 more times at various community organization meetings until the polls open Aug. 8. She says it’s time for the library, and the services it offers in rural areas, to grow.

“We want to dream bigger.”

‘Saudi First’: Kingdom’s bailouts now carry price tag

For decades, Saudi Arabia served as Arab and Muslim nations’ go-to destination for emergency bailouts. But as the kingdom moves toward a post-oil economy, it’s adopting a more transactional approach to aid.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Since its oil wealth blossomed in the 1960s and ’70s, Saudi Arabia has played an almost paternal role as a financier and safety net for Arab and Muslim states. Responding mostly to simple need, an often-forgiving Saudi Arabia has rushed in dozens of times to throw lifelines to crisis-hit allies, doling out billions with zero conditions and few questions. The Saudi billions didn’t even ensure friendly governments.

Yet as Saudi Arabia sought to build a non-oil private sector from the ground up in recent years, it imposed taxes on its citizens for the first time in generations and undertook a deep rethink of its cash bailout policies.

Today Saudi Arabia is replacing its policy of providing unconditional cash aid to allies with targeted investments instead. It’s part of a “Saudi First” foreign policy that puts the interests of the kingdom and its citizens ahead of the geopolitical and domestic interests of its allies – whether they be the United States or fellow Arab countries.

“Investments and economic deals are the way forward,” farmer Abu Nayef says. “Brothers are brothers and business is business. If we give out billions, we as Saudis want to see some return at the end. It’s unfortunate, but economic growth is what drives the world today.”

‘Saudi First’: Kingdom’s bailouts now carry price tag

Abu Nayef remembers a time when, if an Arab country was in trouble, they knew whom to call right away.

“The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia,” says the 60-year-old date farmer. “When any Arab or Muslim state needed financial help, we were always there to fill that need.”

But in 2023, that role has taken on a more self-interested, transactional edge.

Today Saudi Arabia is replacing its policy of providing unconditional cash aid to allies with targeted investments instead. It’s part of a “Saudi First” foreign policy that puts the interests of the kingdom and its citizens ahead of the geopolitical and domestic interests of its allies – whether they be the United States or fellow Arab countries.

“Investments and economic deals are the way forward,” Abu Nayef says. “Brothers are brothers and business is business. If we give out billions, we as Saudis want to see some return at the end. It’s unfortunate, but economic growth is what drives the world today.”

While the new approach makes good financial sense, it represents a fundamental cultural shift for Saudi leadership and a change in the way the country sees its role in the region.

And if many newly tax-paying Saudis welcome the move to ensure that their taxes go to ventures that benefit the country’s economy, others remain nostalgic for the days that the kingdom was everyone’s “big brother.”

Shift in philanthropic philosophy

Since the extraction of its oil wealth blossomed in the 1960s and ’70s, Saudi Arabia has played an almost paternal role as a financier and safety net for Arab and Muslim states.

Responding mostly to simple need, an often-forgiving Saudi Arabia has rushed in dozens of times to throw lifelines to crisis-hit allies, doling out billions with zero conditions and few questions.

In the past 12 years alone, the kingdom has given $3 billion to Jordan, $5 billion to Pakistan, and the bulk of the $92 billion in cash and oil that Egypt has received from Gulf countries since 2011.

Yet increasingly debt-riddled Arab governments, rife with corruption and structural issues they refused or failed to reform, kept coming back with the same need – unconditional financial aid. The Saudi billions didn’t even ensure friendly governments.

As Saudi Arabia began transforming its economy under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in 2016, seeking to build a non-oil private sector from the ground up, it imposed taxes on its citizens for the first time in generations and undertook a deep rethink of its cash bailout policies.

Saudi officials started giving hints or private declarations to delegations coming to Riyadh hat-in-hand: The days of unconditional cash were over.

Instead, the kingdom has been offering to put money into tourism, ports, and banks – projects that would offer a return on investment.

In 2022, the Saudi sovereign wealth fund that is the engine for the kingdom’s own transformation made $24 billion in investments and purchases in Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, Bahrain, Oman, and Sudan.

Implementation of the Saudi philosophical shift was slowed by the COVID-19 pandemic, but it was formally announced this year. Saudi Finance Minister Mohammed al-Jadaan outlined the new approach in January in a speech in Davos, Switzerland.

“We used to give direct grants and deposits without strings attached,” Mr. Jadaan acknowledged. “And we are changing that. ... We need to see reforms” before providing assistance.

“We are taxing our people; we are expecting also others to do the same, to do their efforts,” he said. “We want to help but we want you also to do your part.”

Mansour Almarzoqi, director of the Center for Strategic Studies at the Prince Saud Al Faisal Institute for Diplomatic Studies in Riyadh, emphasizes that encouraging allies’ reforms is the goal.

“The idea behind the ‘no free aid’ policy is to help those countries improve their institutional performance,” he says. “One way of encouraging countries to deal with their structural economic developmental problems is to say, ‘We will help you, but in exchange, you need to tackle this problem, you cannot postpone it any longer.’”

Individual buy-in

In Riyadh, meanwhile, many individual Saudis say they have embraced Saudi First, which comes with an emerging “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” mentality. As part of the crown prince’s Vision 2030, most Saudi citizens no longer receive generous state handouts and are instead encouraged to become entrepreneurs rather than expect a state job.

Improvements to daily life and the overhaul of the economy and infrastructure are noticeable, Saudis say, and they accept the trade-off of income tax and a 16% sales tax.

“We pay taxes, we are good citizens, and we want some of our tax dollars to help our allies,” says Hamad, a Riyadh bank clerk. “But we don’t want to see it wasted by other countries’ bad policies and corruption. What does their government and deficiencies have to do with us?

“‘Saudi First’ means that we can all develop and improve together as partners,” Hamad says. “But when it comes to Saudi money, improving our country and realizing the crown prince’s vision is the priority.”

Encouraged by the fast pace of reforms, government financial support for startups, and international companies opening up shop in the kingdom, many have seized this new entrepreneurial spirit with zeal and say their expectations of other Arab states too have evolved.

“If any person, Arab or otherwise, has a business idea, they can come to the kingdom, get an investor, get residency, open shop, be treated like full citizens with full benefits, can get rich, and keep their money and assets,” says Mohammed, a logistics and cargo manager in Riyadh.

“Saudi Arabia is open for business to anyone without any discrimination,” he says, “but at the end of the day it is business. Saudi Arabia is not a charity anymore.”

Regional impact

The change in Saudi policy is already visible in the region.

With Egypt facing inflation, growing debt, and a currency crisis, Saudi Arabia has balked at buying up Egyptian companies, including the planned acquisition of the United Bank of Egypt, over Cairo’s resistance to implementing International Monetary Fund reforms and steps for transparency in the military-dominated economy.

Jordan, meanwhile, seeking assistance to create jobs and alleviate its 20% unemployment rate, has shifted its approach and is offering Saudi Arabia detailed investment opportunities.

Nevertheless, many Saudis aren’t ready to part with the past. Among them is Salem, who, to keep pace with rising costs in the Saudi capital, works as an Uber driver on his daily commute to and from his office at an engineering firm.

“The idea that we are there to help out our Arab and Muslim brothers and sisters is part of our culture, part of our social traditions as tribes, and is encouraged by our religion, Islam,” he says.

Saudi officials and citizens point out, meanwhile, that the kingdom’s large-scale humanitarian assistance has not stopped.

Saudi Arabia is still dispatching aid, including $100 million in earthquake relief for Syria and $100 million for war-torn Sudan. Last year the kingdom gave $5 billion to help Egypt weather wheat price shocks from the Ukraine war, $600 million to flood-hit Sudanese communities, and $1 billion to Yemen to stabilize its currency.

Um Fahed, a young woman who sells farm products from a stand in Riyadh, says this official humanitarian assistance and the hundreds of millions of dollars Saudi citizens donated via private charities to support Arab and Muslim communities are proof that the culture of generosity in the kingdom is alive and well.

“We still have empathetic hearts. We are still giving money and assistance to charitable causes and humanitarian relief,” she says. “But giving money to governments who keep making the same mistakes, keep refusing to reform and improve, and keep coming back to us and asking for more?

“That is not charity,” she says. “That is being taken for a ride.”

Three picketing writers on why they’re striking

Should a picture be worth a thousand times more than the words? We interviewed three striking Hollywood writers – a newcomer, a mid-career writer, and a veteran – about their tribulations and triumphs.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Across Hollywood, the picket line for writers looks quite similar. Wearing blue Writers Guild of America T-shirts and carrying signs affixed to stakes, the strikers walk a circuit past the gates of each studio. Then they loop back in the opposite direction. At Fox Studios, one writer carries a sign that says, “I’m getting my 10,000 steps in.”

To get to this point in their careers, these writers have also had to put in their 10,000 hours. It’s a profession that often entails late nights and forgoing weekends. The scribes say that studios and streaming services often nickel and dime them to cut costs. On the picket line, as in their jobs, they are accustomed to perseverance.

The strike isn’t a case of rich people fighting rich people, says veteran Wallace Wolodarsky, outside Amazon’s studios.

Asked about the financial pressure that studios and streaming services are under – last month Amazon Studios and Amazon Prime Video laid off 100 of its 7,000 employees – Mr. Wolodarsky responds, “For the most part, middle-class workers have to pay for bad business decisions of huge corporations.”

Three picketing writers on why they’re striking

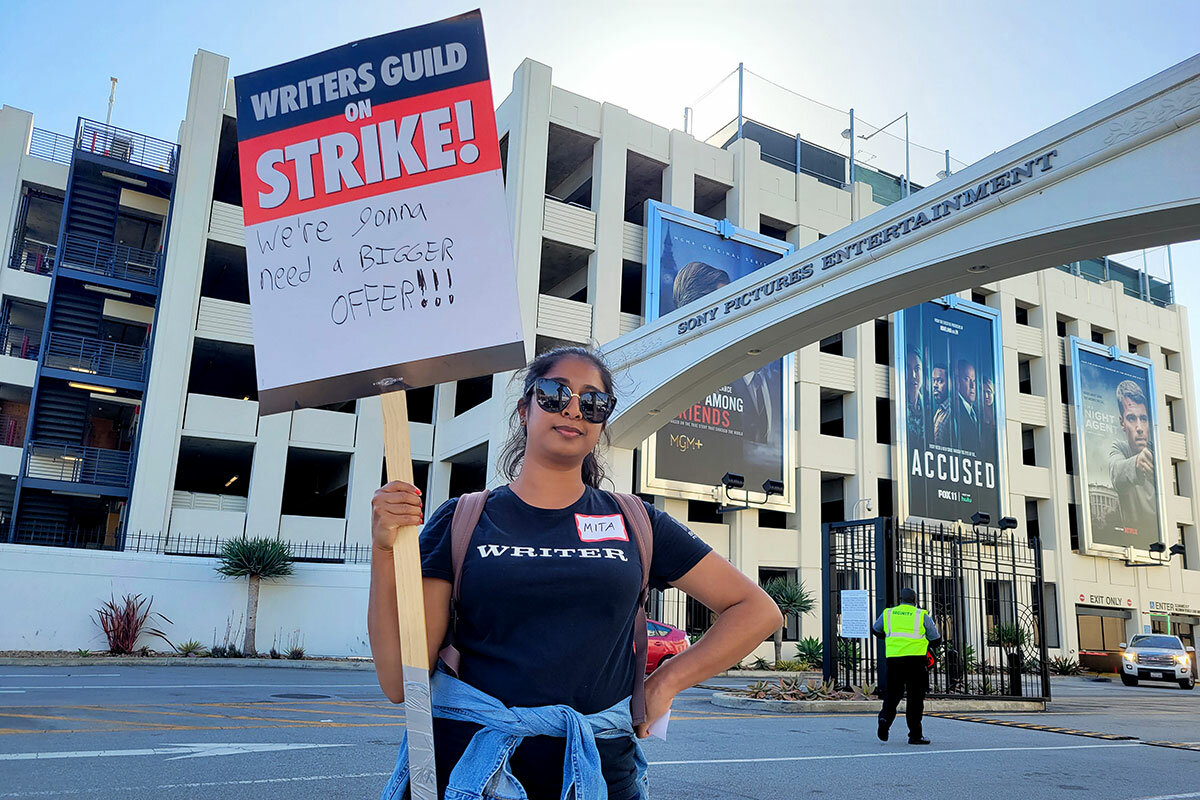

Across Hollywood, the picket line for writers looks quite similar. Wearing blue Writers Guild of America T-shirts and carrying signs affixed to stakes, the strikers walk a circuit past the gates of each studio. Then they loop back in the opposite direction. At Fox Studios, one writer carries a sign that says, “I’m getting my 10,000 steps in.”

To get to this point in their careers, these writers have also had to put in their 10,000 hours. It’s a profession that often entails late nights and forgoing weekends. The scribes say that studios and streaming services (dubbed “streamers”) often nickel and dime them to cut costs. On the picket line, as in their jobs, they are accustomed to perseverance.

The Monitor interviewed three of the people on strike – a newcomer, a mid-career writer, and a veteran – about their tribulations and triumphs in the industry.

The newcomer

Screenwriting is career 2.0 for Mitali Jahagirdar. The young millennial, a first-generation American, graduated from New York University with majors in economics and broadcast journalism. Her first job was as a paralegal.

“It took me a while but, like, I knew that my heart was in Hollywood,” says Ms. Jahagirdar, who is marching outside Sony Studios while carrying a sign that reads, “We’re gonna need a bigger offer!”

She enrolled in an MFA screenwriting program at University of California, Los Angeles. After a stint in the script and continuity department on the reboot of “Dynasty,” she was hired for the Disney sci-fi show “Just Beyond,” for which she was nominated for a WGA Award. Then she was hired as the story editor in a “mini room” – which consists of a showrunner plus two or three writers – to develop an adaptation of Alka Joshi’s novel “The Henna Artist.” But Netflix decided against putting the series into production.

“When you work for 16 weeks, I mean out of a year, that’s not a lot of work,” says Ms. Jahagirdar, raising her voice to be heard over the honks of cars showing support for the writers on strike. When “you’re constantly hustling for that next job ... your mental energy is spent on like, ‘How am I going to pay the rent?’”

When her savings began to dwindle, she started a part-time job on the screenwriting faculty of Western Colorado University.

“I didn’t know anybody in this business when I started. And I want to give back,” she says. “But I genuinely don’t know if I can tell my students, ‘Hey, this is a great business to get into. If you can make it, if you can break in, it’ll be great.’ I can’t see that anymore.”

Ms. Jahagirdar also worked to adapt Colleen Houck’s YA series “Tiger’s Curse” for Netflix, where she has a script development deal under the streaming service’s “Created by Initiative” for underrepresented writers. That project is also in limbo. Yet these setbacks haven’t extinguished her spark.

“There are these stories that we want to tell,” says the writer. “These are lived experiences. We want to see them on the screen. We have observations we’ve made about the world and we share them, whether it’s in a gritty drama or sci-fi fantasy. That’s in our heart.”

The mid-career writer

When Kristin Newman became a Hollywood screenwriter, she never imagined that she’d end up writing a song for Sting.

Picketing outside Fox Studios as her floppy hat wilts under the late-afternoon sun, Ms. Newman reflects on her storied career. After earning a Radio, TV, and Film degree at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, she returned to her hometown of Los Angeles.

“I got a writer’s assistant job because I was a fast typist, and then made friends from there, and wrote scripts and showed them to them,” she recalls.

Ms. Newman’s comedic sensibilities have been employed on series such as “That ’70s Show” and “How I Met Your Mother.” While working on Hulu’s “Only Murders in the Building,” she wrote a song for Sting, who played himself on the series. “I felt comfortable doing it,” she explains, because the lyrics were intentionally bad for comedic effect.

“I’m a TV writer because I don’t want to write alone in a dark room,” says Ms. Newman, who penned a memoir in 2014 titled, “What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding.” “I love the camaraderie and the process that happens when you have lots of people coming together and one plus one equals three.”

Ms. Newman is striking alongside fellow members of the Writers Guild of America because she objects to the trend of writers’ rooms getting smaller. As a cost-cutting move, some streaming services also lay off the writing staff once filming begins.

“I had to really fight to keep one writer with me throughout production for my last show after seeing what had happened to showrunners on streamers who lost their writers’ rooms,” says Ms. Newman. “Then they had to shoot it by themselves and finish breaking stories by themselves and write the scripts by themselves.”

Two days prior to the strike, Ms. Newman was in Argentina filming a TV adaptation of her travel adventure memoir. The showrunner worries what will happen to that dream project, which she’s unable to edit now that she’s on strike. But during the strike outside Fox, she’s reconnected with her friend and fellow writer Dave Caplan.

“We were just talking about how we worked on ‘The Muppets!’ together for ABC,” says Ms. Newman. “I got to have Willie Nelson come and sing ‘On the Road Again’ with the Muppets and introduce my dad to his idol before he died. That was amazing.”

The veteran

Wallace Wolodarsky has co-written so many movies that when he’s asked to name some, he’s at a loss.

“What’s the dog movie where it’s reincarnated?” asks Mr. Wolodarsky, who is marching outside Amazon’s studio in Culver City. “I can’t remember the name of it. ‘A Dog’s Journey,’ maybe.”

He guessed correctly. The veteran co-writes mostly family-oriented movies with his wife, Maya Forbes. Their credits include “Monsters vs. Aliens,” and “Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Dog Days.” More recently, the couple adapted and co-directed Ann Leary’s novel “The Good House,” which starred Sigourney Weaver and Kevin Kline.

This is Mr. Wolodarsky’s third strike during his 35-year membership in the Writers Guild of America. The sign he’s hoisting features a photo of Jerry Lewis from an even earlier strike in 1973. Tensions between studios and writers are long-standing, he says, but the situation is worse than ever for scribes.

“When I came into the business in 1987, I earned a really good living,” says the writer, who got his start on “The Tracey Ullman Show” and “The Simpsons.” “I went from having no bank account to being able to buy a used car and rent an apartment with my girlfriend.”

Glancing at the strikers walking two-by-two along the narrow sidewalk, Mr. Wolodarsky says very few of them are high earners. The strike isn’t a case of rich people fighting rich people, he adds.

“Amazon has got a lot of money and Amazon could pay the writers a fair living, decent wage,” says the writer.

Asked about the financial pressure that studios and streaming services are under – last month Amazon Studios and Amazon Prime Video laid off 100 of its 7,000 employees – Mr. Wolodarsky responds, “For the most part, middle-class workers have to pay for bad business decisions of huge corporations.”

The writer says that he and his wife, who have a 14-year-old son, still try to create movies that captivate audiences amid a fragmented media environment where no one pays attention for more than 30 seconds.

“To me, a great movie is magic in the way that a great novel or a great painting is,” says Mr. Wolodarsky. “I still believe in it. And I’m going to keep doing it till I get kicked out.”

Points of Progress

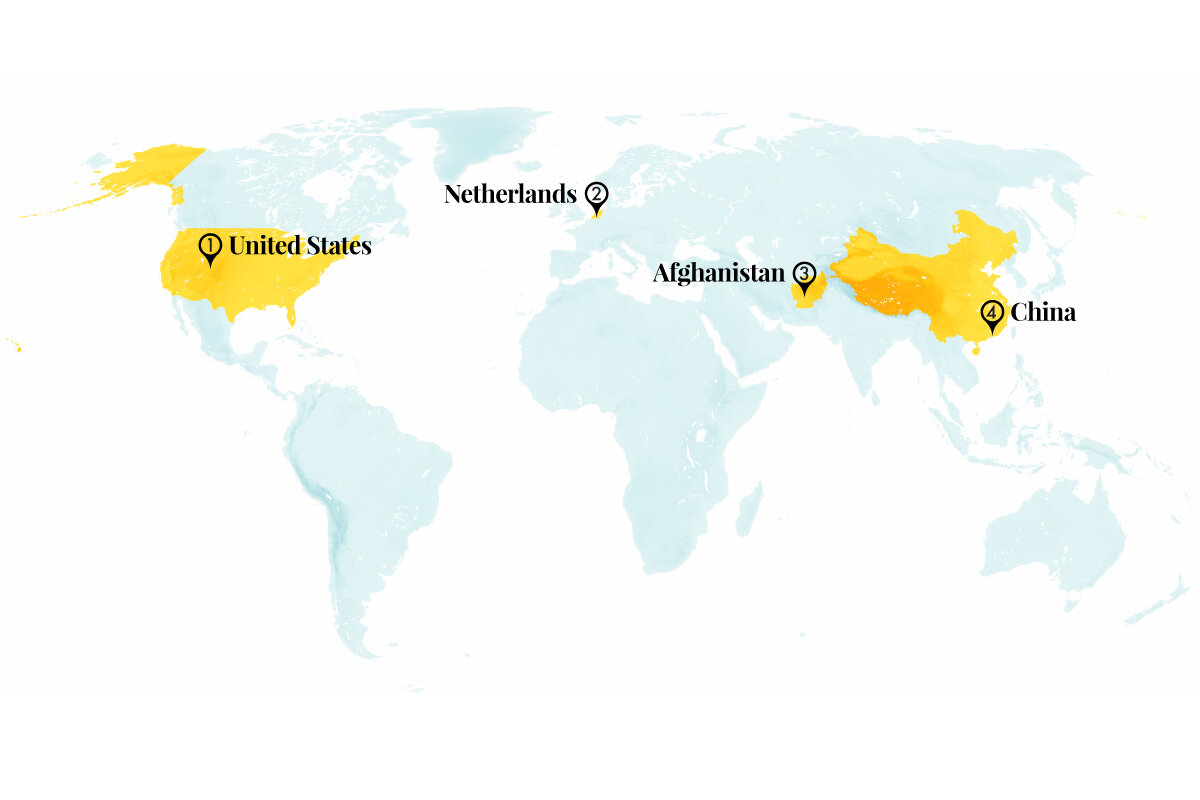

Dark sky in China, TV lessons for Afghan girls

In our progress roundup, new windows on the world are opened. The BBC is offering educational programs for children in Afghanistan who aren’t allowed at school. And in China, a small community is the country’s first certified fighter of light pollution.

-

Angela Wang Staff writer

Dark sky in China, TV lessons for Afghan girls

1. United States

Chemists at Colorado State University designed a process for making a sustainable synthetic plastic. The discovery holds promise for a circular economy based on polyhydroxyalkanoates, or PHAs.

Some living microorganisms make PHAs via bacterial fermentation, but synthetic PHAs are expensive to produce and are more brittle and less durable than petrochemical-based plastic.

The research team set out to improve the heat resistance of PHAs and their ability to be molded from liquid into shapes. The new method also improved recyclability and toughness. The team says its PHAs outperformed both high-density polyethylene and isotactic propylene, which is used to make automotive parts and synthetic fibers. Future applications include everything from packaging to toys.

Sources: Colorado State University, Science, BioResources

2. Netherlands

Amsterdam created more space for bicycles – underwater. Two new underwater garages adjacent to the city’s Central Station house 11,000 spaces for bikes and none for cars. More than 200,000 people arrive at the transportation hub every day, about half of them on bicycles. Because of inadequate legal parking, many riders previously risked ticketing or impoundment to lock their bikes, or they simply left their bikes unlocked. Now they can park for free at the new facilities for up to 24 hours.

Art lines walkways and walls in the light-filled facilities, and curved surfaces are a tribute to the surrounding water. The two garages cost about €85 million ($94 million).

Bicycles account for 36% of all traffic in Amsterdam. The larger redevelopment project of the city’s main railway station aims to welcome more pedestrians and cyclists, and further reduce car use.

“It’s a lovely project, because it’s not a cycling project,” said Marco te Brömmelstroet of Amsterdam University. “It makes visible the real (and often invisible) success factor in Dutch mobility and spatial policy: the bike-train combination.”

Sources: The Guardian, The Verge, Dezeen

3. Afghanistan

Afghan children banned from school can access some education via new weekly television and radio programs. The BBC-produced Dars – which means “lesson” in Dari and Pashto – will air four times a day on the newly launched BBC News Afghanistan channel, as well as on BBC News Pashto and Dari Facebook channels, BBC Persian TV, and on BBC radio throughout Afghanistan. The half-hour episodes are hosted by female Afghan journalists who were evacuated from Kabul during the 2021 Taliban takeover.

The show targets children ages 11 to 16. The Taliban declared shortly after it resumed power that girls would no longer be able to attend school beyond the sixth grade, and in December 2022, it suspended university education for women. In the previous two decades, the country had made strides in educating its girls: According to UNESCO, the female literacy rate had nearly doubled, from 17% to 30%; the number of girls in primary school went from nearly none to 2.5 million; and the number of girls in higher education was more than 100,000, up from 5,000. Today, about 2.5 million girls and young women – 80% – are out of school.

Sources: BBC, UNESCO

4. China

The first place in China to earn International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) recognition is the Xichong community, 60 kilometers (37 miles) from the urban center of Shenzhen. A popular area for surfers and beachgoers, Xichong adopted modifications to outdoor lighting and a commitment to dark sky awareness to achieve IDA “Community” status, one of five levels of certification for fighting light pollution.

With increasing urbanization, excess lighting has negative effects on humans, wildlife, and our ability to observe the night sky. Around 200 places worldwide have IDA status, from vast, remote sanctuaries to communities less than a square mile in size.

The Xichong community includes about 2,500 people from eight villages and the only observatory in southern China. Lin Mei, a research associate at the observatory, says the IDA status “has effectively reduced the night sky background brightness for Shenzhen Observatory, facilitated astronomical observation and research, and created an excellent stargazing destination for all citizens.”

Sources: International Dark-Sky Association, Shenzhen Daily

World

Venture investment in climate technology is 40 times what it was 10 years ago. According to market researcher Holon IQ, venture funding for climate tech startups was up 89% in 2022 over the previous year, pouring $70.1 billion into companies focused on addressing global warming.

Experts attribute the financial push to trends in corporate responsibility and pledges by companies and governments around the world to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The United States invests more than any other region, followed by China, then Europe.

“Venture capital investors are not asking for the highest [return on investment] anymore. They’re asking for a mix of profitability, but also positive impact,” said Raphaele Leyendecker, managing director at Techstars Sustainability Paris Accelerator. “The investment is being redirected to game-changer technologies that are helping the planet actually live longer.”

Sources: Holon IQ, Bloomberg

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Enticing, not inciting, gun owners

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Serbia has joined a small number of countries trying a novel way to reduce gun violence at home. On May 8, after two mass shootings within two days that killed 18 people, the government announced a general amnesty for anyone turning in a gun – illegal or legal. Within a week, more than 13,500 weapons of various types were collected.

More importantly, the amnesty, which runs through June 8, has helped open a dialogue with legal gun owners on their role in perpetuating a gun culture that, in many countries, can lead to a rise in suicides and other gun violence. The Serbian president, Aleksandar Vučić, called the amnesty’s success in collecting guns “a great step forward for a safer environment for our children” and “all our people.”

Gun amnesties are only one tool to entice gun owners into choosing to disarm. Many governments also offer to buy weapons, no questions asked. In Australia, buyback programs and other measures have helped build a political consensus on ways to ensure that gun practices and policies improve safety in a community.

Enticing, not inciting, gun owners

Three decades after bringing mass violence to its Balkan neighbors, Serbia has joined a small number of countries trying a novel way to reduce gun violence at home. On May 8, after two mass shootings within two days that killed 18 people, the government in Belgrade announced a general amnesty for anyone turning in a gun – illegal or legal. Within a week, more than 13,500 weapons of various types were collected.

More importantly, the amnesty, which runs through June 8, has helped open a dialogue with legal gun owners on their role in perpetuating a gun culture that, in many countries, can lead to a rise in suicides and other gun violence. With a population of about 6.8 million, Serbia ranks among the highest in Europe in gun ownership. After the shootings, citizens are now “aware of the risks of keeping guns at home,” one Serbian police official told Associated Press.

The Serbian president, Aleksandar Vucic, called the amnesty’s success in collecting guns “a great step forward for a safer environment for our children” and “all our people.” In addition, the government has proposed tighter rules on gun ownership while many Serbs are calling for curbs on the depiction of fictional gun violence in TV shows and movies.

Gun amnesties are only one tool to entice gun owners into choosing to disarm. Many governments also offer to buy weapons, no questions asked. In Australia, buyback programs and other measures have helped build a political consensus on ways to ensure that gun practices and policies improve safety in a community.

About 20% of guns in Australia have been turned in since 1997 when such incentives were first offered following a mass shooting. “Gun policy reforms were supported by all major political parties,” states a 2022 study by the University of Sydney. “The success of firearm regulation has since become a source of pride for many Australians.”

Serbia has a long way to go to achieve what President Vucic calls the “almost complete disarmament” of the country. Yet like many countries, it is now learning to engage gun owners rather than enrage them. Fostering a dialogue about people’s motives for gun ownership – such as lack of trust in government or fear of crime – can bring a society together to look at the core foundations for peace.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Harmony is not the exception

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

Recognizing that we’re God-created to express harmony and wholeness – not injury or discord – has a healing impact.

Harmony is not the exception

We all can probably recall instances of harmony in our daily lives. For example, it might have been a seamless coming together of ideas when a project demanded a team effort. Or a feeling of peace and freedom after an illness or injury was healed. But is harmony an occasional coincidence, dependent on circumstances beyond our control?

Most of us have been moved at one time or another by harmony in music. It’s humbling to know that there are musical principles of harmony that all musicians have access to – but don’t originate – that enable them to produce infinite expressions of harmony.

This has helped me appreciate even more fully something I’ve learned in Christian Science: that there is a source of spiritual, permanent harmony that is totally reliable in all aspects of our lives. This source is God, and His law of harmony empowers us to overcome discord, uplifts us, brings deeper meaning to our lives, and even heals.

The Bible is filled with messages of God’s supreme power and presence – such as this one: “I am the Lord, and there is none else, there is no God beside me” (Isaiah 45:5). Stories in the Bible show over and over how God’s powerful goodness transforms and heals. The infinite divine nature includes pure harmony, which destroys inharmony in the same way that light destroys darkness – by revealing that it never truly had substance to begin with.

As God’s children, we’re entirely spiritual, made to reflect the Divine. Recognizing that harmony is ours because God expresses it in each of us enables us to experience it in very tangible ways. We begin to see how natural it is for us to feel the blessed harmony of God.

A few years ago I began to have aggressive pain in my hip. Because I had effectively relied on prayer as taught in Christian Science – rooted in the Bible – for years for needs of all kinds, I began to pray. My prayers affirmed that since God, the only legitimate cause, is good, He is incapable of causing pain. It simply couldn’t truly be part of me, since I was the very loved child of God, who harmoniously governs our existence.

These ideas gave me greater conviction, but the pain was still there. I began to pray with a passage in a book entitled “Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science. It references one of Jesus’ healing works, in which he cast out “a devil” – the inability to speak – from someone.

Mrs. Eddy says this about it: “It could not have been a person that our great Master cast out of another person; therefore the devil herein referred to was an impersonal evil, or whatever worketh ill. In this case it was the evil of dumbness, an error of material sense, cast out by the spiritual truth of being; namely, that speech belongs to Mind instead of matter, and the wrong power, or the lost sense, must yield to the right sense, and exist in Mind” (p. 190).

This helped me see the illegitimacy of the evil of pain, inflexibility, and restriction of movement – what the material senses were saying about my condition. The spiritual truth is that qualities of harmony and freedom have their source in the one ever-present and ever-available God. Therefore, they are unlimited, constant, and part of our true identity as God’s complete expression.

I wholly accepted this as the reality, gaining a greater consciousness of harmony as God-given and wholly apart from materiality. I felt an immediate uplift, and in the next few days, the condition just faded away.

Maybe every day doesn’t feel like a full-blown symphony. But acknowledging and honoring God as the one and only source of good, we can feel a simple but sweet harmony that flows more consistently through our days and naturally blesses everyone it touches.

Viewfinder

The power of play

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Please come back tomorrow, when staff writer Christa Case Bryant will have a report from the U.S.-Mexico border amid the expiration of Title 42.