- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- In Eagle Pass, Texas, the border crisis is complicated

- Biden and Trump vie to be labor’s best friend

- Armenians flee Azerbaijani victors in Nagorno-Karabakh

- Ukraine’s cautious bid to restore ‘community’ of school

- Math lovers wanted: US needs more in order to thrive

- Truth, forgiveness, exploration: 10 best September reads

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The travails and joys of ‘getting there’

Sometimes, the most challenging thing about a story can be just getting there. That’s been the case here in Bangladesh, where photographer Melanie Stetson Freeman and I are on the last leg of a global project about youth facing climate change.

It started months ago with the visa – which I wasn’t sure I’d get despite countless phone calls, emails, and trips to the consulate. It came five days before our planned departure. Then there was the matter of getting to the capital, Dhaka. Sudden storms meant aborting our approach minutes before landing and instead heading to Kolkata. That led to six drama-filled hours on a runway, as India would not let us off the airplane (because of the Pakistanis on the flight), and we couldn’t take off again until we got approval from Boeing itself. (There was more, but I’ll spare you.)

Once in Dhaka, “getting there” meant going slowly. Very slowly. At all hours, going just a few miles took hours amid a cacophonous, color-splashed, belching wall of traffic. Outside Dhaka, “getting there” got scarier. Much scarier. Cars, trucks, passenger buses – the most terrifying of all – rickshaws, bicycles, dogs, goats, and people share highways where the only rule seems to be “never yield.”

Yet commuting can also be a joy. I’m writing this on a passenger ferry crossing the wide Padma River, where vendors are hawking puffed rice served with chiles, cucumbers, and lime. Everyone asks where we’re from and takes a selfie with us. In a country with more than 700 rivers, we’ve taken every manner of water vessel. The journey we’ve had to take most frequently: crossing the Pusur channel while keeping our balance on a tiny, standing-room-only boat.

They are the anecdotes and adventures that almost never make it into published articles. But for journalists, “getting there” can sometimes be what we remember most.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In Eagle Pass, Texas, the border crisis is complicated

Residents of Eagle Pass, Texas, live with the border crisis in ways most of the rest of the U.S. does not. They want a secure border. They also want humane treatment of migrants.

Living and working by the Rio Grande, Margil Lopez is at the heart of the migrant crisis. Yet it took a trip to the hospital with his father for him to grasp the scale.

“It took us five hours to even see the doctor,” he says.

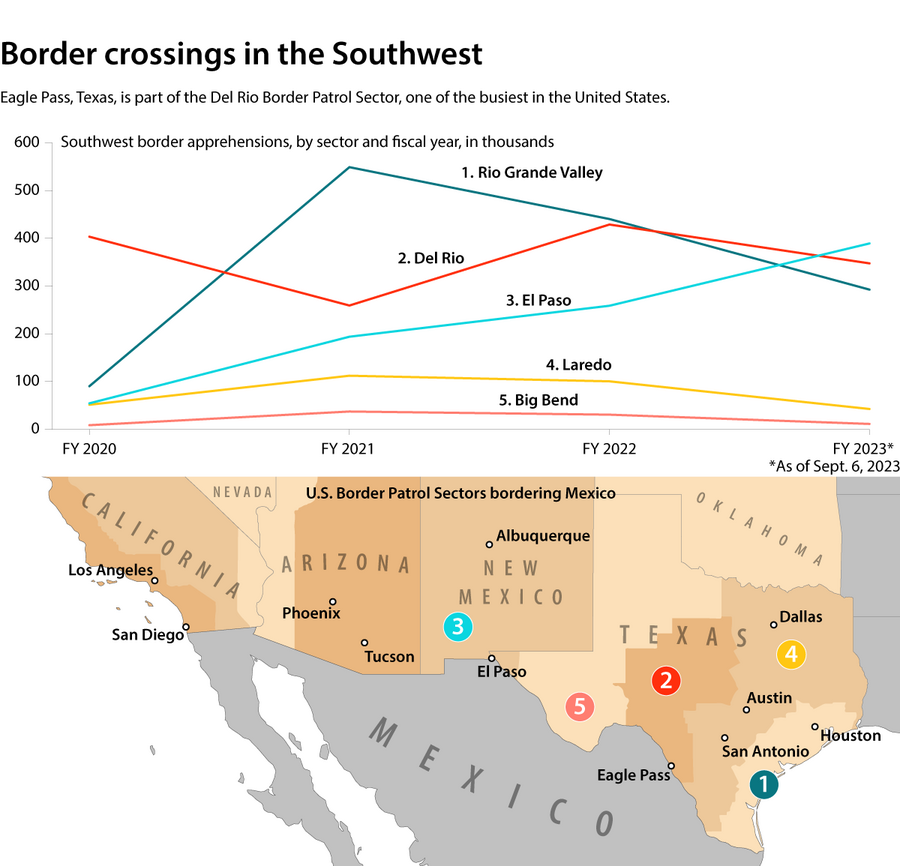

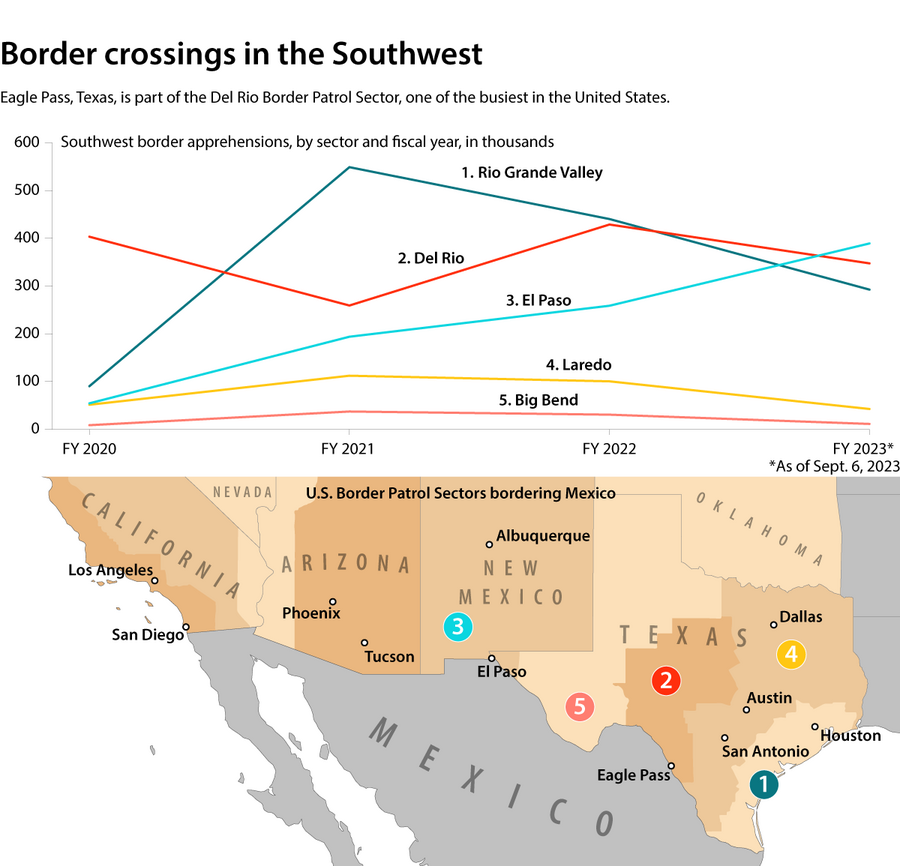

For over a year, Eagle Pass has seen more migrant crossings than almost any other U.S. border city.

In an unprecedented venture into immigration enforcement by a state, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott launched Operation Lone Star in 2021. The $4.4 billion initiative has seen state police and National Guard members patrolling the Rio Grande and blockading the river with razor wire and floating buoys buttressed with nets and saw blades.

Meanwhile, Mayor Rolando Salinas issued a disaster declaration last week after thousands of migrants crossed in just two days.

For Eagle Pass residents, the crisis is provoking a complex range of emotions. Border security is a necessary piece of local law enforcement. Many locals, descended from legal immigrants, take umbrage with illegal immigration, and they count U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents as neighbors and relatives. But many residents view the buoy barrier and razor wire as steps too far.

“Nobody wants to take full accountability,” says Mr. Lopez. “It’s just straining the resources of small little towns along the border.”

In Eagle Pass, Texas, the border crisis is complicated

Living and working less than 2 miles from the Rio Grande, Margil Lopez is at the heart of the United States’ migrant crisis. Yet it took a trip to the hospital, after his father threw his back out, for him to grasp the scale of the crisis in the small town of Eagle Pass, Texas.

“It took us five hours to even see the doctor,” he says.

For over a year, this rural sector of the southern border has seen more migrant crossings than almost any other. The Biden administration has been responding with a combination of carrots and sticks, from creating new legal pathways for certain migrants to continuing a policy of rapidly expelling certain other migrants. But the state of Texas has been responding here as well, and with much more aggression.

In an unprecedented venture into immigration enforcement by a state government, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, a Republican, launched Operation Lone Star in 2021. The $4.4 billion border security initiative has seen state police and National Guard members – reinforced by National Guard units from other Republican-led states – patrolling the Rio Grande, arresting migrants who trespass on private property, and blockading the river with shipping containers, razor wire, and floating buoys buttressed with nets and saw blades.

Operation Lone Star has been controversial since its inception. Public officials and human rights groups have criticized the initiative as inhumane and unlawful. Some rank-and-file service members have objected to the operation as well. Texas is fighting a federal lawsuit seeking to remove the floating barrier.

Meanwhile, migrants have continued to enter Eagle Pass illegally – and recently they’ve done so in large numbers. Mayor Rolando Salinas issued a disaster declaration last week after thousands of migrants crossed into the city in just two days. “It has taken a toll on our local resources, specifically our police force and our fire department,” he told the San Antonio Express-News.

For Eagle Pass residents, the crisis is provoking a complex range of emotions. Border security is a necessary piece of local law enforcement here, especially in recent years. Many locals, descended from legal immigrants, take umbrage with illegal immigration, and they count U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents as friends, neighbors, and relatives. Businesses have also benefited from the patronage of state police and the National Guard.

At the same time, residents are increasingly alienated by the state-led intervention in the city. Many view the buoy barrier and razor wire as steps too far. Rents have spiked as thousands of personnel have been posted on monthslong deployments, and emergency services that locals rely on are overwhelmed.

“I feel like the investment was pointless,” says Mr. Lopez. “It’s also kind of inhumane.”

The way the crisis is being handled by both the federal and state governments, he adds, “is like releasing a dam and not preparing for the flood of water going in every single direction and how it affects the communities that are at the brunt of it.”

“He asked for water and for Border Patrol”

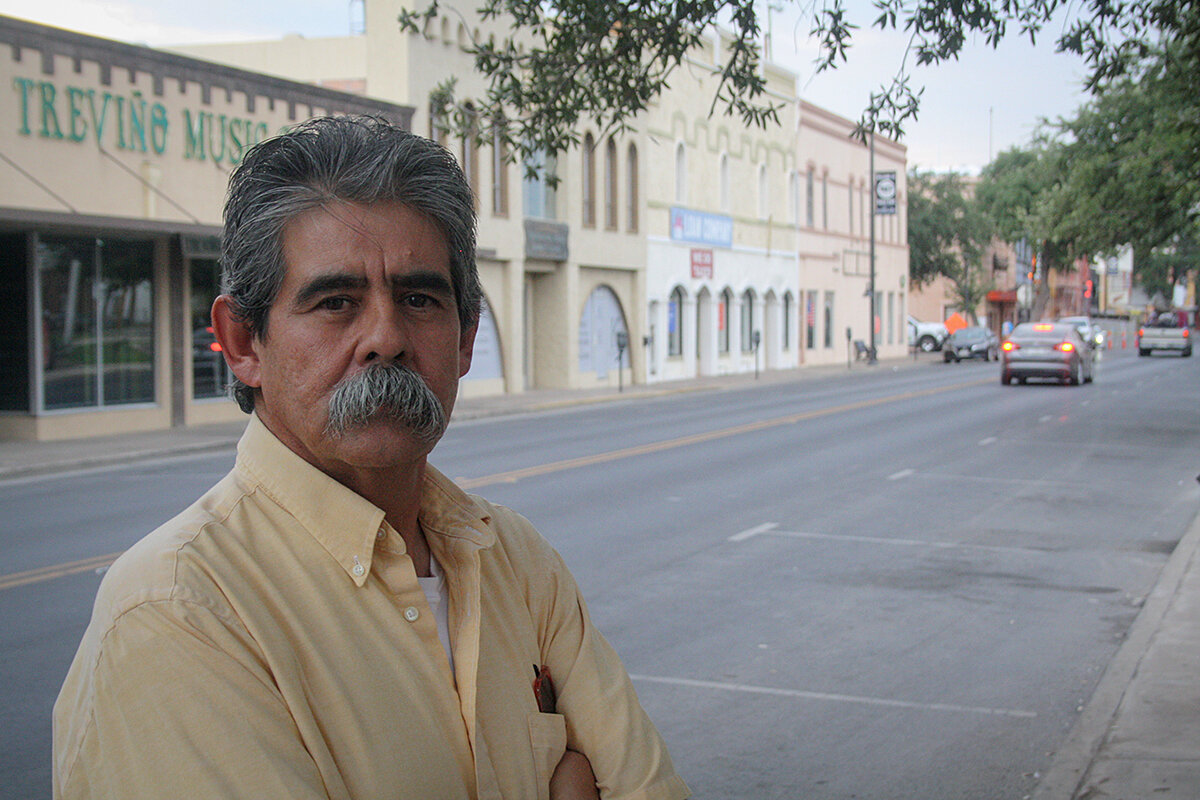

Earlier this summer, on a 110-degree Fahrenheit day, Raul Riza found a migrant collapsed in his trailer yard about 2 miles from the border.

“He asked for water and for Border Patrol,” he says. And while that encounter may not have been threatening, he often sees migrants knocking on doors in neighborhoods on the edge of town, and he’s heard of migrants breaking into homes.

Thus, Mr. Riza supports what the state has been doing with Operation Lone Star, including busing migrants to the White House and blue cities like New York and Los Angeles. That also includes deploying the buoys and razor wire. Born and raised in Eagle Pass, the manager at a local gym says the federal government hasn’t been doing enough to help the town cope with the huge numbers of migrants on its doorstep.

When former President Donald Trump was in office, “they’d been handling it good,” he adds. Since President Joe Biden replaced him, “it’s just like they opened the gates and let them in.”

With a population just over 28,000 and the local resources to match – Eagle Pass has two hospitals, a police force of about 100 people, and only one migrant shelter – the city isn’t equipped for being the busiest crossing point on the southern border.

And last week saw a spike in migrants, with a reported 9,000 crossing in a week. The sudden surge also caused the Border Patrol to temporarily block vehicle and rail traffic from Mexico into Eagle Pass. The closure of such a vital source of local revenue also motivated the recent disaster declaration.

“Every day the bridge is closed we are losing money,” Mayor Salinas told The New York Times last week.

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection; Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse

Late last week, U.S. and Mexican government officials struck an agreement to make new efforts to deter migrants traveling north to the U.S. border. Mexico agreed to deport migrants to their home countries in Latin America – a potentially significant agreement since the U.S. doesn’t have relations with countries many asylum-seekers are fleeing, like Venezuela and Nicaragua – and to more closely monitor migrants using the country’s train system to travel north, CNN reported.

“Migrants themselves, as well as smugglers, change their tactics day by day, hour by hour” at the border, says Doris Meissner, a senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute.

“The issue of people hopping onto trains and traveling on the tops of trains is just so dangerous and so desperate,” she adds. “If they’re now coming to the table and committing to addressing that, that could be significant.”

“Now everything’s peaceful”

For Jessie Fuentes, reactions to the migrant surge last week have been overblown. Speaking a few days after the disaster declaration had been made, he said the city was quiet again.

“It was a little crazy, but now everything’s peaceful,” he added.

The chaos in Eagle Pass and on this section of the border is as much due to the Texas government as the migrants. For decades, local authorities have had good working relationships with Customs and Border Protection and with Mexican officials. And in Texas’ border cities, Border Patrol is a well-regarded employer and community member.

The involvement of state personnel has upset the status quo in Eagle Pass, says Mr. Fuentes, owner of Epi’s Canoe & Kayak. Border Patrol has been operating in the city for 150 years, “and there’s never been a barrier built. There’s never been mistreatment of individuals like is currently happening,” he adds.

State officials have pointed to arrest and drug-seizure statistics as evidence of the difference Operation Lone Star is making. Through 2022, the initiative has led to over 23,000 criminal arrests and over 21,000 criminal charges, Governor Abbott’s office reported. Those numbers represent just a fraction of the nearly 1.3 million border encounters logged by Border Patrol in Texas in 2022, however.

Yandi Fragela was one of those 1.3 million encounters. A native of Cuba, he says he fled to Nicaragua because of the Castro regime, but then fled to the U.S. because of government repression in Nicaragua.

The journey aged him, he says, with the jet-black hair and goatee he flaunted as a drummer replaced by a shaved head and beard riddled with gray. He’s been saving and gathering materials to apply for a special green card for Cuban citizens, watching the migrant crisis grow worse and worse.

While he understands why so many migrants are trying to enter the U.S., he also understands why authorities here have been responding with some force. He also admits that the buoy barrier is “aggressive,” and has only had the effect of forcing migrants to cross in more dangerous places.

“It’s difficult. I am [an asylum-seeker], but there are too many people crossing,” he says. “Migration is a right for every person, but a country needs to take care of its people, too.”

Who is in charge of the border?

What Texas is doing may not be legal, however. Courts have long held that immigration enforcement is a federal government function, and while border states can enforce state law in border regions, Texas might have taken it too far.

“Texas law enforcement doesn’t have immigration enforcement authority. That’s not going to change. The authority is federal authority,” says Ms. Meissner.

Operation Lone Star “is an enormous commitment of resources and cost for taxpayers in Texas, but it still is considerably more a political statement than it is a law enforcement operation,” she adds.

Rep. Eddie Morales Jr., who represents Eagle Pass in the state Legislature, wants to see the state take a different approach.

In 2021, he was the only Democrat in his chamber to vote to commit nearly $2 billion to state border security initiatives, including Operation Lone Star. His views have changed, however, in part due to revelations like those described by a state trooper in July in an internal email of children and pregnant women getting caught in razor wire and troopers being ordered to push migrants back into the river.

“That’s when I thought we overstepped the line,” he said at the Texas Tribune Festival last weekend.

“We can’t just throw money at this,” he added. Given the limits on state power in immigration matters, “we need to think outside that box.”

In a letter to Governor Abbott last year, he outlined what he would like the state government to help with. Expanding and improving land ports and roads into and around border cities can help boost the already-thriving trade relationship between the U.S. and Mexico; a migrant workforce program can curb the migrant crisis and fill job vacancies statewide.

Across the state, Texans are similarly divided over the state’s activities on the border. A majority of Texas voters support placing buoys and barbed wire at the Rio Grande, according to an August poll by the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas at Austin, and a majority support deploying additional state police and military resources to the border.

Mr. Lopez says he thinks most Americans are “in the middle” when it comes to the migrant crisis. Yes, there needs to be border security. And yes, migrants need to be treated like human beings.

Meanwhile, the city is in the middle of reinventing itself. Five years ago he returned to Eagle Pass to open a bakery with his sister. It’s one of several new businesses that have opened in recent years. Young people who left for college are returning and taking leadership positions in local arts and business groups. Historic buildings are being restored, and there’s talk of developing a park and walking area to complement a similar park across the bridge in Piedras Negras, Mexico.

“It’s a really cool time to be in Eagle Pass and be involved with the changes that are happening,” Mr. Lopez says. But amid the migrant crisis, the city is also “a mess.”

“Nobody wants to take full accountability,” he adds. “It’s just straining the resources of small little towns along the border.”

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection; Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse

Biden and Trump vie to be labor’s best friend

Back-to-back appearances with autoworkers in Michigan by President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump underscore the importance of working-class voters in the Midwest, at a time when unions are exercising their clout.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

President Joe Biden’s trip to suburban Detroit on Tuesday was about so much more than a show of support for striking autoworkers.

It was history in action – the first time a sitting American president joined a picket line. It was an effort by a struggling Democratic president with a personal narrative centered on working-class values to woo a key voting bloc. And it was effectively the launch of the 2024 general election campaign.

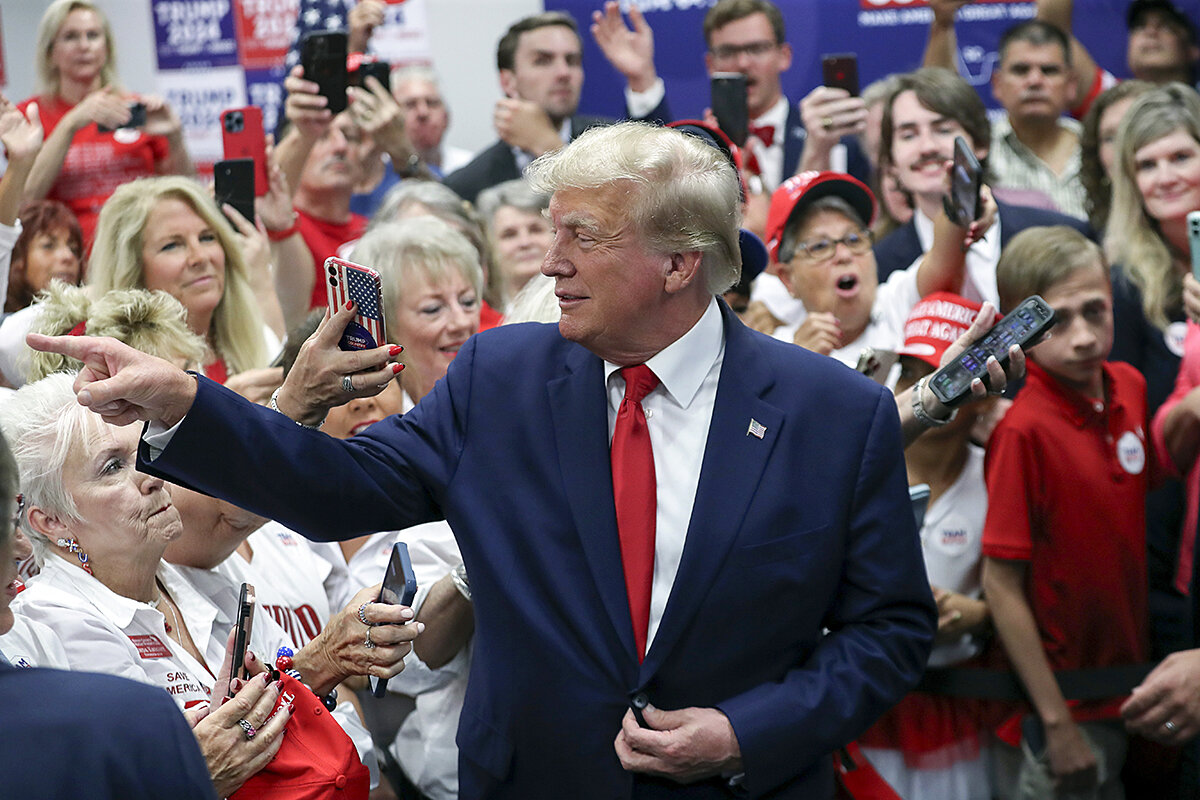

Former President Donald Trump, President Biden’s likely opponent in 2024, is skipping the Republican primary debate Wednesday night and delivering a prime-time speech in Detroit to current and former union members.

For Mr. Biden, Tuesday's trip reflects a larger Democratic effort to shore up support among blue-collar voters, who have been shifting toward the Republican Party in recent years. Mr. Trump’s populist pitch was key to winning the crucial battleground states of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania in 2016 – all states that Mr. Biden then took back in 2020. Now, both he and Mr. Trump – deadlocked in 2024 polls – are pouncing early.

“Union support of Democrats has not been monolithic, and this is the latest version of that contest,” says Michael Traugott, professor emeritus of political science at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Biden and Trump vie to be labor’s best friend

President Joe Biden’s trip to suburban Detroit on Tuesday was about so much more than a show of support for striking autoworkers.

It was history in action – the first time a sitting American president joined a picket line. It was an effort by a struggling Democratic president with a personal narrative centered on working-class values to woo a key voting bloc. And it was effectively the launch of the 2024 general election campaign.

Former President Donald Trump, President Biden’s likely opponent in 2024, is skipping the Republican primary debate Wednesday night and delivering a prime-time speech in Detroit to current and former union members. The Trump campaign called Mr. Biden’s picket-line appearance “nothing more than a cheap photo op.” The White House responded by noting that Mr. Biden was personally invited by the president of the autoworkers’ union.

“Stick with it. You deserve a significant raise and other benefits,” Mr. Biden told the picketers.

For Mr. Biden, Tuesday's trip reflects a larger Democratic effort to shore up support among blue-collar voters, who have been shifting toward the Republican Party in recent years over cultural and economic issues and a distrust of elites. Mr. Trump’s populist pitch was key to winning the crucial battleground states of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania in 2016 – all states that Mr. Biden then took back in 2020. Now, both he and Mr. Trump – deadlocked in 2024 polls – are pouncing early.

“Union support of Democrats has not been monolithic, and this is the latest version of that contest,” says Michael Traugott, professor emeritus of political science at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. “There’s a lot of economic anxiety that comes partially from growing income inequality in the American population.”

Workers striking against the big three U.S. automakers – General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis – are demanding a 40% wage hike and full-time pay for a 32-hour work week. Mr. Biden has offered statements of support for the United Auto Workers union, but avoided commenting on specific demands. The UAW has yet to make an endorsement in the 2024 presidential race, but Mr. Biden has been endorsed by the AFL-CIO and 17 other unions.

The strike – which expanded last week to additional GM and Stellantis plants, but not Ford, amid signs of progress in talks with that company – threatens to harm the American economy at a delicate moment. And therefore Mr. Biden’s appearance on the picket line Tuesday is risky: If the strikes drags on, and becomes unpopular, he owns it. Mr. Biden has pushed hard for electric cars, including financial incentives contained in the Inflation Reduction Act, but autoworkers are concerned about job security. Electric cars require fewer workers to build, and there’s no guarantee they will be produced in union shops.

Mr. Trump has criticized the UAW leadership, saying that their union is heading for obsolescence, as most electric cars will soon be built in China. “The autoworkers are being sold down the river by their leadership,” he said in an interview on NBC’s “Meet the Press.” Unlike Mr. Biden, the former president will not be joining a picket line Wednesday, instead speaking to about 500 workers at a non-unionized auto-parts manufacturer in Macomb County, near Detroit. Mr. Trump’s speech was announced before Mr. Biden’s plan to come to Detroit.

“Joe Biden has been forced to come join the picket line ... because of the fact that Trump basically called his card,” says Rocky Raczkowski, chair of the Oakland County GOP in suburban Detroit.

Mr. Raczkowski, like Mr. Trump, argues that union leaders have failed workers by aligning with the Democrats and their climate agenda, including the transition to electric cars, while foreign companies increase their market share. “The corporate bosses of these companies are in favor of Democratic leaders and Democratic leadership and not fighting back,” he says.

As the 2024 campaign ramps up, Mr. Trump’s policies vis a vis union workers are also likely to garner more scrutiny.

“Trump talks a lot about his solidarity and plays into the anger of particular groups,” says Peter Berg, a professor of employment relations at Michigan State University. “But when you look at what he actually does in his policies, they’re pretty mainstream conservative.”

Mr. Trump’s appointees to the National Labor Relations Board weren’t particularly union-friendly, Professor Berg notes. The Trump NRLB took steps to limit employees’ rights to organize in certain workplaces and made it easier for workplaces to get rid of existing unions and to classify workers as independent contractors.

“Trump probably ran the most vehemently anti-union administration we’ve seen in decades,” says Democratic strategist Steve Rosenthal, a former political director of the AFL-CIO. He also characterizes Trump Supreme Court appointees as hostile to labor.

On the other hand, some of Mr. Trump’s actions on trade – such as imposing stiff tariffs on certain imports, and renegotiating trade agreements – drew praise from labor leaders.

Mr. Biden’s record on labor includes strong support for unions and the right to collective bargaining, and his appointees to the NLRB have worked to reverse some of the Trump administration’s policies. In his first two years in office, he got numerous job-generating bills through Congress, including massive investments in climate, infrastructure, and semiconductor manufacturing. Mr. Biden also proudly advertises a law restoring the pensions of more than a million people that had been underfunded.

This week’s showdown in Detroit harks back to the 2016 election, when Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton gave short shrift to union-aligned households and lost to Mr. Trump.

“She didn’t make the traditional stops, didn’t visit union halls or plants in Michigan or steel mills in Pennsylvania,” says Mr. Rosenthal. “She essentially was saying to those union workers, this election is not about you, and it showed.”

In that election, Mrs. Clinton won union households in Michigan 53% to 40% according to exit polls – a smaller margin than Democratic nominees typically have received. In 2020, Mr. Biden won the union vote in Michigan 62%-37%. The other two “blue wall” states, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, showed similar turnarounds for the Democratic ticket among union members in 2020.

Mr. Biden has to keep reassuring blue-collar voters on economic matters, even as some disagree with him on cultural matters, such as gun rights, Democratic strategists say.

“Blue-collar folks have felt like they’ve been screwed for 40 years, that no one was paying attention to them, that the establishments of both parties were not looking out for them and there was a lot of bitterness about that,” says Mike Lux, a Democratic consultant who has worked with unions.

“Trump was the ultimate anti-establishment guy – anti-Republican Party establishment and anti-Democratic Party establishment – and some people saw in him someone who would shake things up,” Mr. Lux adds.

One key voting bloc in the 2024 race will be nonwhite voters who have not finished college – a group that includes many UAW workers.

In his 2012 reelection, President Barack Obama won nonwhite working-class voters by a 67-point margin. Last week, a New York Times/Siena poll showed Mr. Biden’s lead over Mr. Trump within that cohort at a much narrower 49%-33%. Third-party candidates and voters choosing to stay home are other things that worry Democrats, whose likely nominee does not generate intense enthusiasm among base voters to the degree that Mr. Trump does.

Staff writer Sophie Hills contributed to this report.

Armenians flee Azerbaijani victors in Nagorno-Karabakh

Thousands of ethnic Armenians are not waiting to see whether they can trust the Azerbaijani troops who seized their enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh last week. They are fleeing their homes despite pledges of fair treatment from their historic enemies.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Astrig Agopian Contributor

The exodus from Nagorno-Karabakh has begun.

Ethnic Armenians, who have long lived in the enclave surrounded by Azerbaijani territory, are flooding into Armenia. Some 19,000 are believed to have fled, and thousands more are said to be planning to follow them if only they could find gas for their cars.

Last week, a lightning offensive by Azerbaijani troops forced the breakaway enclave’s leaders to capitulate, putting an end to recurrent hostilities that have simmered in the Caucasus since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

It is unclear how many of the 120,000 ethnic Armenians living in Nagorno-Karabakh will flee their homes when they get the chance, but few of them are ready to put much trust in their historic enemies and new masters, the Azerbaijanis.

Speaking by phone from Nagorno-Karabakh, one young woman describes scenes of chaos and panic. “My mother’s cousin died, my friend’s brother; we have a lot of people missing,” she explains. “It’s very simple. I don’t want all my friends and family to die, even if that means we don’t keep our homeland. We need to evacuate now.”

Armenians flee Azerbaijani victors in Nagorno-Karabakh

One by one, in a steady stream, cars, trucks, and minivans crawl past the checkpoint, the first on Armenian territory, as their Armenian drivers flee the disputed enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh, seized a week ago in a lightning offensive by Azerbaijani troops.

Among them, his navy blue car’s roof rack loaded with what remains of his life, an older man cries quietly as he leaves his ancestral homeland.

“What can I say? It’s over, we lost everything,” says the man, who gives only his first name, Arsen. “We left everything behind, and we are leaving. Where are we even going? I don’t know,” he says.

More than 19,000 ethnic Armenian refugees have fled Nagorno-Karabakh since separatist authorities and self-defense militia there surrendered to Azerbaijani forces, according to an Armenian government estimate. Several thousand more are said to be looking for fuel and a way out of the region. While Azerbaijan insists it wants to “reintegrate” the 120,000 ethnic Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians into Azerbaijan, the refugees do not trust the authorities and fear repression and more violence.

“They shelled us and killed some of us and then asked us, ‘Do you want to go?’ What do you think? Does the world really not understand what is going on? Is that a real choice?” Arsen asks angrily.

A wooden cross dangles from the rearview mirror. His wife is looking back, talking on the phone with relatives. “I have family in Armenia, but how many days can you stay at someone else’s house? I am a refugee now. Depending on someone to give me some bread if he wants to,” says Arsen, tears rolling down his cheeks.

Armenia and neighboring Azerbaijan have been fighting over Nagorno-Karabakh, an Armenian-populated enclave within Azerbaijan, since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Tens of thousands of people died and more than a million were forced to flee their homes on both sides before 2,000 Russian peacekeepers stepped in three years ago to monitor a cease-fire agreement that ended the most recent bout of hostilities.

Since the invasion of Ukraine, Moscow’s attention has been elsewhere, and President Vladimir Putin has also been angered by the way Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has distanced himself from traditional ally Russia.

Moscow has neglected some of its cease-fire obligations, including its pledge to guarantee freedom of movement for people and goods along the Lachin Corridor, a road that links Nagorno-Karabakh with sovereign Armenian territory. Azerbaijan took advantage of this last December to close the route, leading to serious shortages of food, medicines, and other necessities in the breakaway region.

“What did the Russians do? Nothing, zero,” complains Gayane Sargsyan, a resident of Stepanakert, the capital of Nagorno-Karabakh, in a phone call. “They watched us in the blockade. Azerbaijan starved us; we lived without electricity, water, and food.”

The 29-year-old woman, who is still trapped in Nagorno-Karabakh, unable to find enough fuel to leave the enclave with her family, says she is surrounded by chaos and panic. “My mother’s cousin died, my friend’s brother; we have a lot of people missing,” she explains. “It’s very simple. I don’t want all my friends and family to die, even if that means we don’t keep our homeland. We need to evacuate now.”

Fearing she will never be able to return home, Ms. Sargsyan is visiting all the places she loves in her native city and taking pictures, in order not to forget. “The terrible choice we have is whether to bury our relatives or not; we don’t want to flee and leave them behind,” she says.

The Azerbaijani authorities, meanwhile, insist that they are facilitating the provision of humanitarian supplies to residents of Nagorno-Karabakh and suggest that there is no massive exodus of Armenians. “Those who want to go are mostly family members of military personnel,” Hikmet Hajiyev, foreign policy adviser to the Azerbaijani president, wrote in a tweet.

“Azerbaijan is also preparing its own plan with regard to the short-term and mid-term political, social, and economic reintegration” of ethnic Armenian residents, and would discuss it with local leaders, Mr. Hajiyev told Al Jazeera television. He pledged that those fighters who surrendered their weapons would be free to return home, and that his government would pursue only a handful of leaders accused of war crimes against civilians during the first war.

While peace negotiations are underway between the Azerbaijan government and officials from Nagorno-Karabakh, the European Union on Tuesday hosted a meeting in Brussels of senior officials from Azerbaijan and Armenia, who are expected to prepare the ground for a pre-arranged meeting between Prime Minister Pashinyan and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev next month in Spain.

The terms of any peace treaty remain cloudy, though Azerbaijan, which forced Nagorno-Karabakh defense forces to capitulate last week, clearly has the upper hand.

Three scenarios are conceivable, says Tigrane Yégavian, an expert on the Caucasus who teaches at the Paris campus of Schiller International University. “A first possibility could be to open a humanitarian corridor with pressure from the international community, since the Russians do not really seem to be willing to do that,” he says.

“A second scenario would be to protect Nagorno-Karabakh like Kosovo, but that seems unlikely, given the international community’s lack of a response for now,” Mr. Yégavian adds.

“The third possibility is that Azerbaijan will actually get what it wants ... several hundred people, civilian and military officials, to judge them in Baku. And in exchange, maybe Azerbaijan will facilitate the evacuations and empty the region,” the expert concludes.

Azerbaijan’s victory in Nagorno-Karabakh may not mark the end of hostilities in the South Caucasus, some observers warn. Azerbaijan, backed by its close ally Turkey, has designs on part of Armenia’s Syunik province, which lies between Azerbaijan and its exclave, Nakhchivan. On Monday, Azerbaijani President Aliyev and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan held a meeting in Nakhchivan, ostensibly to launch a gas pipeline.

“The Armenian government has a rationale of making successive concessions in exchange for a hypothetical peace. But there are fears that Azerbaijan is not going to stop here, as it has territorial claims over the region of Syunik in Armenia too,” Mr. Yégavian says.

Back in the city of Goris, people evacuated from Nagorno-Karabakh are already thinking about long-term plans – and they do not include a return to their homes.

“I am a hard worker, we all are,” says Parkev Agababyan, who was evacuated from Nagorno-Karabakh. ”If we get a little help from the government, we will find jobs and houses, and start our lives again in Armenia. But if war starts again here, then where can we go?” he wonders. “The only thing I know is that we will not go back. I have a family, and I want them to be safe.”

Ukraine’s cautious bid to restore ‘community’ of school

Another academic year is starting amid war in Ukraine, and some students are going back into classrooms. Schools have to fortify their facilities, but educators and parents view the in-person experience as worth the risk.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

As Ukraine’s 5.1 million school-age children go back to their studies for the fall, the reality of war is becoming part of academic considerations. And this year, a third of Ukrainian students are going back to in-person classes full time – if their schools are properly protected.

“A school can only fit as many children as can fit in a [bomb] shelter,” explains Damian Rance, UNICEF’s advocacy chief in Ukraine.

But Ukrainians are undaunted. Their commitment to education is visible in efforts to repair schools and provide online learning to children both in Ukraine and abroad as refugees.

Local officials, parents, and teachers stress that it is not only about education. Just as important is the chance for children to be outside the family environment and make friends. For those who have lost relatives, hidden in basements as rockets rained down, or experienced the prolonged absence of parents serving on the front, it’s a lifeline.

“We all want to be in the classroom,” says Lydia Rusan, who gave up refugee status in Switzerland to return to Irpin, Ukraine, to teach. “All the children want to be with their classmates. They don’t want to study online because they miss each other. The most important thing for them is to be together.”

Ukraine’s cautious bid to restore ‘community’ of school

It was the bomb shelter at Irpin Lyceum No. 17 that clinched Anna Onyshenko’s decision to enroll her son Ivan there for the new school year.

She knows that the shelter doesn’t guarantee anything. “There is no such thing as 100% safe in Ukraine,” says Ms. Onyshenko, an accountant.

But as Ukraine’s 5.1 million school-age children go back to their studies for the fall, the reality of war is becoming part of academic considerations. More than 300 educational institutions have been destroyed due to Russia’s attacks against Ukraine. Ten times as many have been damaged. A Russian drone attack on a school in the border region of Sumy recently killed four people.

And this year, a third of Ukrainian students are going back to in-person classes full-time – if their schools are properly protected. “A school can only fit as many children as can fit in a shelter,” explains Damian Rance, UNICEF’s advocacy chief in Ukraine, during the reopening of another Irpin school completely rebuilt after being destroyed by Russian artillery and missile strikes.

But Ukrainians are undaunted. Their commitment to education is visible in efforts to repair schools and provide online learning to children both in Ukraine and abroad as refugees.

Local officials, parents, and teachers stress that it is not only about education. Just as important is the chance for children to be outside the family environment and make friends: an opportunity rendered even more precious by the horrors of war. For those who have lost relatives, hidden in basements as rockets and shells rained down, or experienced the prolonged absence of parents serving on the front, it’s a lifeline.

“We all want to be in the classroom,” says Lydia Rusan, an English teacher who gave up refugee status and village life in Switzerland to return to Irpin. “All the children want to be with their classmates. They don’t want to study online because they miss each other. The most important thing for them is to be together, even if it is a difficult time.”

Cozy, comfortable, and safe

Kharkiv is a city pining for normality. You see it in the morning rush of parents dressed for work dropping off their children at the underground metro schools and playgrounds full of life at sundown.

Scores of windows remain boarded up above ground. Russian tanks are no longer in striking distance, but the regular wail of sirens warning of incoming missiles and periodic explosions still shakes the streets. That’s why the metro system was the obvious place to attempt a seminormal school year with educators and children finally gathering in person.

Some children are driven to this school just one flight of stairs under University Station in the city center. Others arrive on foot. The majority come in buses escorted by the police and are shepherded down by their school principals, who wear orange scarves for visibility. Security is taken seriously – even by 7-year-old David, who arrives clutching a toy wooden tank for comfort. “It’s great,” he says of the school.

The site is shared in shifts by children of different schools and grade levels. Bound by a long corridor, seven classrooms and a room reserved for the school nurse overhang the subway tracks. A Japanese ventilation system refreshes the air. The narrow classrooms are split by two columns of desks, bookended by a screen projector and a soft play area.

“We’ve really tried hard to make things as cozy and comfortable for the children – and we’ve taken all the safety precautions,” says Victoria Kuznetsova, the metro station supervisor who has added school traffic and safety to her list of responsibilities. Private security guards help guard the space and keep potentially unsavory characters at bay.

Everyone agrees there is no substitute for human connection. The decision to open schools in Kharkiv’s metro system was driven by parents and local officials who took that to heart. “It’s impossible to replace all the human warmth and motion of an in-person classroom with gadgets,” says Lyudmila Usychenko, a school principal who was shepherding third graders into the metro after a night of missile strikes on the city.

“Here I can see, hear, and touch them – that’s so important,” stresses Olha Zakhariva Harbuz, a second grade teacher making an autumn leaves painting with her students. “All together we form a bubble. Teachers have full responsibility for their students, whether in the metro or outside in the streets. At least here in the metro, we feel safer because it is underground. That matters because we can be calm and not so stressed about it all.”

There are five such schools in Kharkiv. They depend on 186 teachers and tutors, 30 psychologists, 21 nurses, and 56 technical support staff members. But the children benefiting from that in-person contact remain the exception rather than the rule. Of the 111,000 students enrolled in the Kharkiv education system, only 52% are physically present in the area. The metro schools can accommodate only about 11,000 students.

“The children who are now attending first grade did not have a chance to go to preschool or kindergarten,” says Valerii Shepel, deputy head of education for Kharkiv. “This is their first real social interaction.”

He is clear on what he wants them to take away from the experience: “The ability to talk to each other and hear each other,” he says. “The main cause for conflict between people is the inability to hear each other.”

“It is important to see other children”

Olena Andrushok and her crew are hard at work in Lyceum No. 11 of Izium, a town 77 miles southeast of Kharkiv. Women scrape clean walls in classrooms devoid of children. Others sweep the floor. Sawdust fills the air as men make repairs. Parts of the school remain in ruins, walls covered in soot.

This has been Ms. Andrushok’s school since 1978, so tears overtook her on seeing the extent of the damage when Ukrainian soldiers drove out Russian ones.

“If we put our noses down, we will never succeed in anything,” says the headmaster, who started as a first grader and then returned as a teacher. “We need to put our noses up and move forward, work hard, and hope for the best. We aspire to have offline education, but it all depends on front-line dynamics. Fifty kilometers [31 miles] is not that far away.”

The classrooms are empty. On paper, the school’s student population is higher than before the war. It used to count 460 students. Now it has 720 students assigned to it because other schools were destroyed. Of these, 420 are physically around Izium, and the remainder have fled abroad or to safer parts of Ukraine with their families. They all follow the Ukrainian school curriculum online as best they can – older ones drawing on habits built during the pandemic, little ones struggling to connect with the process.

The school remains an anchor point for a community that carries deep traumas linked to a Russian occupation marred by killings and torture. About 80% of high-rise buildings in Izium have been partially or completely destroyed, according to local authorities. The same applies to 30% of the picturesque shingle roof, single-story homes embedded in overgrowing gardens. Mines and unexploded ordnance remain a threat.

Nine-year-old Semen Kaliuzhnyy is one of hundreds of children across Ukraine who spent substantive time sheltering in a basement. Now the brightly lit basement of Lyceum No. 11 provides him and 13 others with an entirely different experience. With the help of SOS Children’s Villages, a nongovernmental organization focused on protection and advocacy for children, the space has been converted into a digital learning hub complete with a ball pit, shelves of board games, and art supplies for the children to enjoy. Resources are still limited, but in the coming months local authorities hope to open more digital learning hubs and, if the situation is safe enough, resume regular classes in person.

The laughter of playtime during breaks is contagious. But to this serious boy, who chopped wood with his father to help warm the family over winter, the best treat is the cacao snack. He misses the meat soup served at the now-destroyed school kitchen. “It was really good,” he says.

Olena Cherniavska bikes to the hub twice a week for the sake of her 9-year-old daughter, Alina. Russian artillery pounded their village and forced them to flee to the Czech Republic. The desire to be close to her husband brought them back again. They rent a house because theirs was destroyed.

“Alina still worries that the alarms won’t ring in time,” shares Ms. Cherniavska as sirens disrupt math exercises. “But I am glad she has this space. It is important to see other children.”

Ms. Andrushok knows it will be a long time before the school is repaired and the situation allows all her children and teachers to return. But she is determined. “This is not the end of the road,” she says. “It is only the beginning.”

Reporting for this story was supported by Oleksandr Naselenko.

Math lovers wanted: US needs more in order to thrive

Math scores may feel distant from most people’s lives. But a U.S. math deficit raises questions about how the country plans to protect its economic competitiveness and national security. This story is part of The Math Problem, the latest project from the newsrooms of the Education Reporting Collaborative.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

-

By Jon Marcus The Hechinger Report

American high school students say they get why their classmates don’t like math.

“It’s a struggle. It’s constant thinking,” says Steven Ramos, a 16-year-old from Massachusetts who says he plans to become a computer or electrical engineer.

Teen attitudes offer insight at a time when Americans joke about how bad they are at math and scores on standardized tests are falling. Employers and others say America’s poor math performance isn’t funny anymore. It’s a threat to the country’s global economic competitiveness and national security.

“The advances in technology that are going to drive where the world goes in the next 50 years are going to come from other countries, because they have the intellectual capital and we don’t,” says Jim Stigler, a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Also at stake are the future earnings of American young people, and the ability of U.S. employers to have a pipeline for jobs in the semiconductor and electric vehicle industries, for example. Key to turning things around is nurturing the interest of those who do like numbers.

“It’s the only subject I can truly understand, because most of the time it has only one answer,” says Peter St. Louis-Severe, a teen who hopes to be a mechanical or chemical engineer. “Who wouldn’t like math?”

Math lovers wanted: US needs more in order to thrive

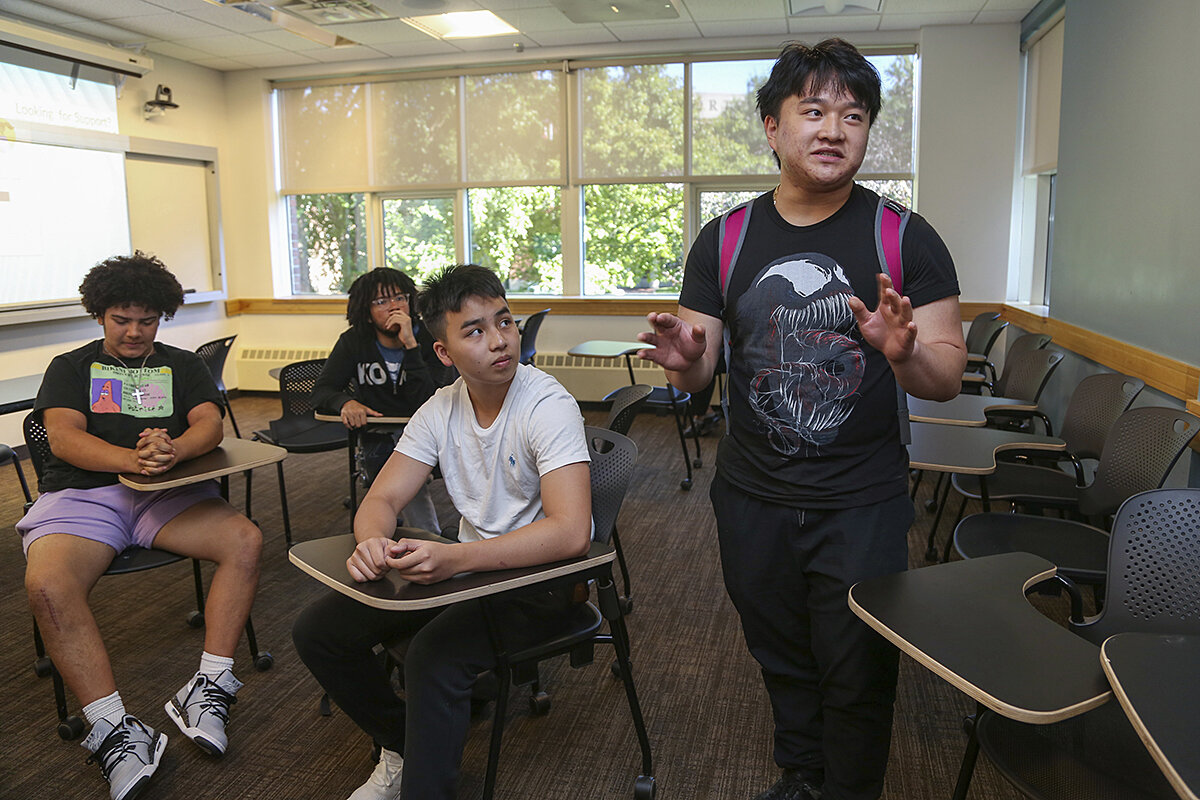

Like a lot of high school students, Kevin Tran loves superheroes, though perhaps for different reasons than his classmates.

“They’re all insanely smart. In their regular jobs they’re engineers, they’re scientists,” says Mr. Tran, who is 17. “And you can’t do any of those things without math.”

Mr. Tran also loves math. He is speaking during a break in a city program for promising local high school students to study calculus for five hours a day throughout the summer at Northeastern University in Boston. And his observation is surprisingly apt.

At a time when Americans joke about how bad they are at math, and already abysmal scores on standardized math tests are falling even further, employers and others say the United States needs people who are good at math in the same way motion picture mortals need superheroes.

They say America’s poor math performance isn’t funny anymore. It’s a threat to the nation’s global economic competitiveness and national security.

“The advances in technology that are going to drive where the world goes in the next 50 years are going to come from other countries, because they have the intellectual capital and we don’t,” says Jim Stigler, a psychology professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, who studies the process of teaching and learning subjects including math.

There’s already ample and dramatic evidence of this.

World challenges require math

Several largely overlooked reports, including from the Department of Defense, raise alarms about how Americans’ disdain for math is a threat to national security.

One, issued in July by the think tank The Aspen Institute, warns that international adversaries are challenging America’s longtime technological dominance. “We are no longer keeping pace with other countries, particularly China,” it says, calling this a “dangerous” failure and urging decisionmakers to make education a national security priority.

“There are major national and international challenges that will require better math skills,” says Josh Wyner, vice president of The Aspen Institute and founder and executive director of its College Excellence Program.

“This is not an educational question alone,” says Mr. Wyner. “It’s about knowledge development, environmental protection, better cures for diseases. Resolving the fundamental challenges facing our time require math.”

The Defense Department, in a separate study, calls for an initiative akin to the 1958 Eisenhower National Defense Act to support education in science, technology, engineering, and math, or STEM. It reports that there are now eight times as many college graduates in these disciplines in China and four times as many engineers in Russia than in the United States. China has also surpassed the United States in the number of doctoral degrees in engineering, according to the National Science Foundation.

Meanwhile, the number of jobs in math occupations – which “use arithmetic and apply advanced techniques to make calculations, analyze data, and solve problems” – will have increased by 29% in the 10 years ending in 2031, or by more than 30,000 per year, Bureau of Labor Statistics figures show. That’s much faster than most other kinds of jobs.

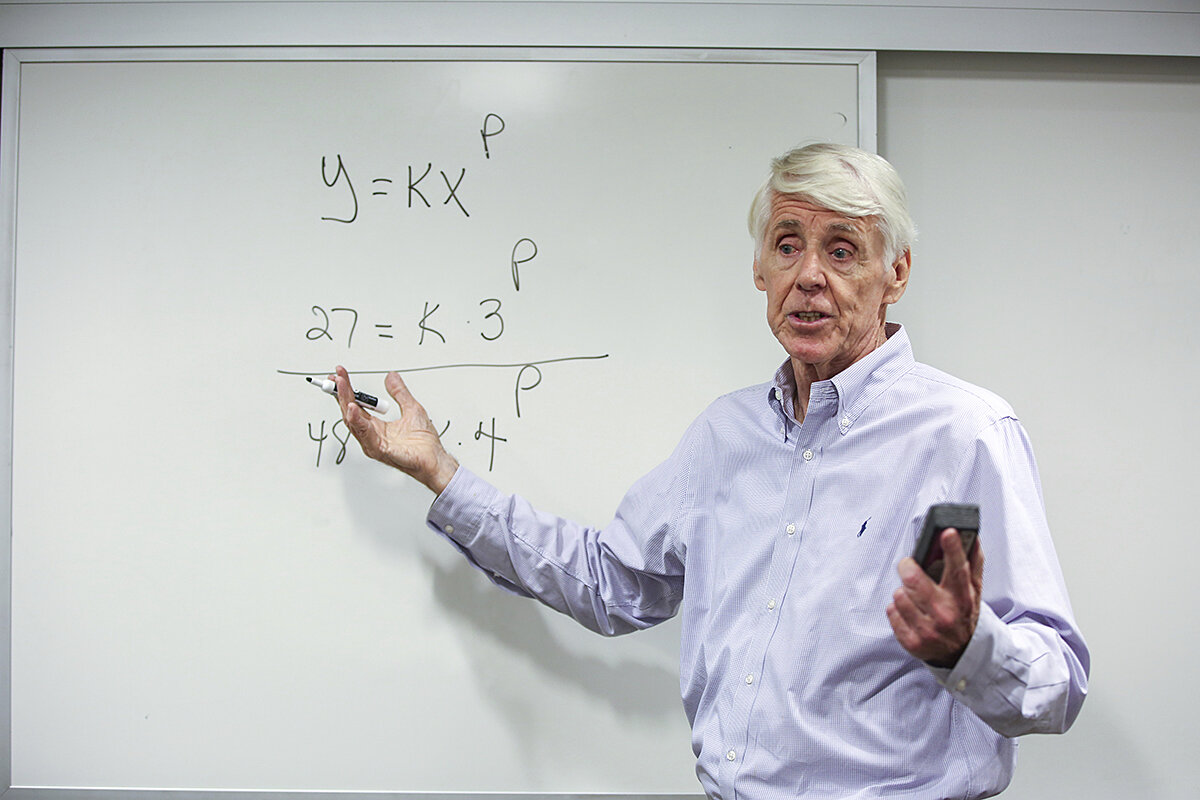

“Mathematics is becoming more and more a part of almost every career,” says Michael Allen, who chairs the math department at Tennessee Technological University.

Tennessee Tech runs a summer camp teaching cybersecurity, which requires math, to high school students. “That lightbulb goes off and they say, ‘That’s why I need to know that,’” Professor Allen says.

There are deep shortages of workers in information technology fields, according to the labor market analytics firm Lightcast, which says that there were more than 4 million job postings over the last year in the United States for software developers, database administrators and computer user support specialists.

With billions being spent to beef up U.S. production of semiconductors, Deloitte reports a projected shortage in that industry, too, of from 70,000 to 90,000 workers over the next few years.

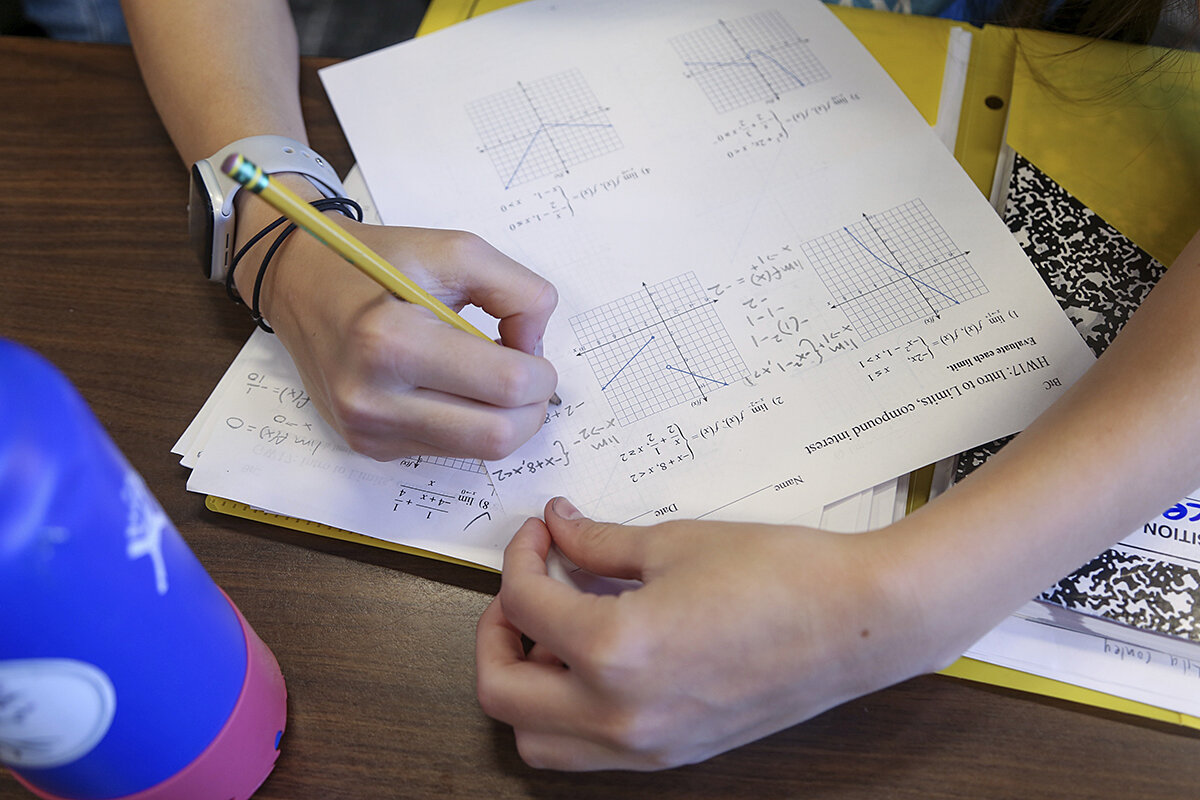

All of these careers require math. Yet math scores among American students — which had been stagnant for more than a decade, according to the National Science Foundation — are now getting worse.

Math performance among elementary and middle-school students has fallen by 6% to 15% below pre-pandemic growth rates, depending on the students’ age, since before the pandemic, according to the Northwest Evaluation Association, which administers standardized tests nationwide. Math scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress fell by 9 points last year, the largest drop ever recorded, to their lowest levels in more than three decades.

In the most recent Program for International Student Assessment tests in math, or PISA, U.S. students scored lower than their counterparts in 36 other education systems worldwide. Students in China scored the highest.

Math = economic growth

Even before the pandemic, only 1 in 5 college-bound American high school students was prepared for college-level courses in STEM, according to the National Science and Technology Council. Among the students who decide to study STEM in college, more than a third end up changing their majors, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

“And these are the students who have done well in maths,” says Jo Boaler, a British author who studies the teaching of math as a professor at the Stanford University Graduate School of Education. “That’s a huge loss for the U.S.”

One result of this exodus is that, in the fast-growing field of artificial intelligence, two-thirds of U.S. university graduate students and more than half the U.S. workforce in artificial intelligence and AI-related fields are foreign born, according to the Georgetown University Center for Security and Emerging Technology.

Only around 1 in 5 graduate students in math-intensive subjects including computer science and electrical engineering at U.S. universities are American, the National Foundation for American Policy reports, and the rest come from abroad. Most will leave when they finish their programs; many are being aggressively recruited by other countries, such as Canada and the United Kingdom.

The economic ramifications of this in the United States are twofold: first, on individuals’ job prospects and earnings potential; and second, on the country’s productivity and competitiveness.

Every one of the 25 highest-paying college majors are in STEM fields, the financial advising website Bankrate found.

Ten years after graduating, math majors out-earn graduates in other fields by about 17%, according to an analysis by the Burning Glass Institute using the education and job histories of more than 50 million workers. That premium would be even higher if it wasn’t for the fact that 16% of math majors become teachers.

Knowing math “is a huge part of how successful people are in their lives and what jobs are open to them, what promotions they can get,” Professor Boaler says.

A Stanford economist has estimated that, if U.S. pandemic math declines are not reversed, students now in kindergarten through grade 12 will earn from 2% to 9% less over their careers – depending on what state they live in – than their predecessors educated just before the start of the pandemic. The states themselves will suffer a decline in gross domestic product of from 0.6% to 2.9% per year, or a collective $28 trillion over the remainder of this century.

Countries whose students scored higher on math tests have experienced greater economic growth than countries whose students tested lower, one study found. It calculated that had the U.S. improved its math scores on the PISA test as promised by President George H. W. Bush and the nation’s governors in 1989, it would have resulted in a 4.5% bump in the U.S. gross domestic product by 2015. That increase did not occur.

“Math matters to economic growth for our country,” says Mr. Wyner, of The Aspen Institute.

This is among the reasons that it isn’t only schools that have been pushing for more students to learn math. It’s economic development agencies such as the Michigan Economic Development Corporation, which is trying to get more students into STEM so they can fill jobs in fields such as semiconductor production and electric vehicle design, in which the state projects a need for up to 300,000 workers by 2030.

“Math just underpins everything,” says Megan Schrauben, executive director of the Michigan Department of Labor and Economic Opportunity’s MiSTEM initiative to improve STEM education. “It’s extremely important for the future prosperity of our students and communities, but also our entire state.”

Getting young people on board

The top reason young people ages 13 to 18 say they wouldn’t consider a career in technology is that it requires math and science skills, a survey by the information technology industry association and certification provider CompTIA finds. Forty-six percent fear they aren’t good enough in math and science to work in tech, a higher proportion than their counterparts in Australia, Belgium, India, the Middle East and the U.K.

In Massachusetts, which is particularly dependent on technology industries, employers are anticipating a shortage over the next five years of 11,000 workers in the life sciences alone.

“It’s not a small problem,” says Edward Lambert Jr., executive director of the Massachusetts Business Alliance for Education. “We’re just not starting students, particularly students of color and from lower-resourced families, on career paths related to math and computer science and those things in which we need to stay competitive, or starting them early enough.”

The Bridge to Calculus program at Northeastern, where Mr. Tran spent his summer, is a response to that. The 113 participating students were paid $15 an hour, most of it from the city and its public schools, the program’s coordinator, Bindu Veetel, says; the university provided the classroom space and some of the teachers.

The students’ days began at 7:30 a.m., when teacher Jeremy Howland roused his sleepy-looking charges by having them run exercises in their heads, such as calculating 20% of various figures he’d written on the whiteboard.

He wasn’t doing it to show them how to leave a tip. He wanted them to explain their thought processes.

“I can see the wheels turning in your head,” Mr. Howland told the sea of faces in front of him one early morning as knees bobbed and pens drummed on pages of paper notebooks crowded with equations.

The students’ daily two-hour daily calculus class got only tougher after that. Slowly the numbers yielded their secrets, like a mystery being solved. One of the students even corrected the teacher.

“Bada-bing,” Mr. Howland said whenever they were right. “OK, now you’re talking math.”

Students used some of the rest of their time learning how to apply that knowledge, trying their hands at coding, data analysis, robotics, and elementary electrical engineering under the watchful supervision of mentors including previous graduates of the program.

“We show them how this leads to a career,” says Ms. Veetel, who says the program’s alumni have gone on to software, electrical and civil engineering, math research, teaching, medical, and other careers. “They have so many options with math. Slowly that spark comes on, that this is something they can do.”

“Who wouldn’t like math?”

It’s not just a good deed that Northeastern is doing. Some of the graduates of Bridge to Calculus end up enrolling there and proceeding to its highly ranked computer science and engineering programs, which – like those at other U.S. universities – struggle to attract homegrown talent.

More than half of the graduate students in all disciplines at Northeastern, including those that require math, are foreign born, university statistics show. In his field of engineering management, “80% of us are Indian,” Suuraj Narayanan Raghunathan, a graduate student serving as a Bridge to Calculus mentor, says with a laugh.

The American high school students say they get why their classmates don’t like math.

“It’s a struggle. It’s constant thinking,” says one, Steven Ramos, 16, who says he plans to become a computer or electrical engineer instead of following his brother and other relatives into construction work.

But with time, the answers come into focus, says Wintana Tewolde, also 16, who wants to be a doctor. “It’s not easy to understand, but once you do, you see it.”

Peter St. Louis-Severe, 17, says math, to him, is fun. “It’s the only subject I can truly understand, because most of the time it has only one answer,” says Mr. St. Louis-Severe, who hopes to be a mechanical or chemical engineer and whose gamer name is Mathematics Boss. “Who wouldn’t like math?”

Not everyone is convinced that a lack of math skills is holding America back.

“We push so many kids away from computer science when we tell them you have to be good at math to do computer science, which isn’t true at all,” says Todd Thibodeaux, president and CEO of CompTIA.

What employers really want, Mr. Thibodeaux says, “is trainability, the aptitude of people being able to learn the systems and solve problems.” Other countries, he says, “are dying for the way our kids learn creativity.”

Back in their classroom at Northeastern, students spent a brief break exchanging math jokes, then returned to class, where even Mr. Howland’s hardest questions generally failed to stump them.

They confidently answered as he grilled them on polynomial functions. And after an occasional stumble, they got all the exercises right.

“Bada-bing,” their teacher happily responded.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct what the acronym STEM stands for.

This piece is part of The Math Problem, an ongoing series documenting challenges and highlighting progress, from the Education Reporting Collaborative, a coalition of eight diverse newsrooms: AL.com, The Associated Press, The Christian Science Monitor, The Dallas Morning News, The Hechinger Report, Idaho Education News, The Post and Courier in South Carolina, and The Seattle Times. To read more of the collaborative’s work, visit its website.

Books

Truth, forgiveness, exploration: 10 best September reads

Self-discovery is a vital part of being human. Readers this month will find characters who, often through powerful relationships, grow significantly as they learn to define themselves.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Monitor contributors

Human beings are defined and enriched by their relationships.

Many of the characters in this month’s fiction learn to grow as individuals as they grapple with bias, search for truth, and struggle with loss.

In Zadie Smith’s historical novel about an infamous Victorian trial, for example, an Australian butcher claims to be the missing heir to an English fortune. The case exposes class conflicts, with working-class people taking up for the butcher and the upper echelon dismissing his claims. In the process, Smith dives deep into her characters’ inner psyches, deftly probing questions about identity, class, and bias.

And in nonfiction, Ross Gay’s introspective “The Book of (More) Delights” reflects on the small joys that give life meaning. In a series of charming essays, he demonstrates a vivid appreciation for the complexity of the human condition and seeks to answer many of the questions that reverberate throughout this month’s book selections.

Truth, forgiveness, exploration: 10 best September reads

1 The Fraud

by Zadie Smith

Zadie Smith’s historical novel about the notorious Victorian-era case of an Australian butcher claiming to be a long-missing heir to an English fortune raises ever-relevant questions about identity, class, bias, and how we separate truth from falsehood. It’s another bravura performance from Smith.

2 North Woods

by Daniel Mason

“North Woods” follows the story of a house in the woods of western Massachusetts and its occupants over four centuries. This dazzling novel intertwines the often tragically truncated lives of its characters and its wooded setting, all gorgeously captured in multiple literary styles, genres, and voices.

3 The Last Devil To Die

by Richard Osman

The fourth installment of Richard Osman’s “Thursday Murder Club” investigates a local antiques dealer’s point-blank execution. When a death at the retirement home forces a pause, the friends grieve, pay tribute – and grow. It’s a poignant new chapter in the bestselling series.

4 The Secret Hours

by Mick Herron

In Mick Herron’s superb thriller, a moribund investigation into the British Secret Intelligence Service lurches into gear when evidence of malfeasance lands in the agency’s lap. Bouncing between present-day London and mid-1990s Berlin, the expertly crafted tale probes political machinations, bureaucratic holdups, and the temptations of revenge. Come for the banter and Briticisms; stay for the conviction that it’s never too late to right past wrongs.

5 Others Were Emeralds

by Lang Leav

In her winning adult fiction debut, Lang Leav follows four close friends – all children of immigrants to Australia – as they navigate high school pressures, tiffs, and love on the cusp of the 21st century. When a racist confrontation leads to tragedy, Ai, the Cambodian Chinese teen at the novel’s center, must balance the solace she finds in art with the need to mourn and forgive.

6 Beyond the Door of No Return

by David Diop

From Booker Prize-winning author David Diop comes a story-within-a-story that builds with quiet force. While studying Senegal’s rich flora in 1749, young French botanist Michel Adanson meets a young Wolof woman. He falls head over heels, even as the turbulent alliances, rivalries, and dangers of the slave trade threaten them both. Wise to the ways truth shifts with its tellers, Diop has created a resonant novel.

7 The Heart of It All

by Christian Kiefer

Christian Kiefer’s portrait of a small Ohio factory town facing the twin problems of economic decline and cultural divides is indispensable reading. Tempering realism with empathy, the novel does not shy away from its characters’ struggles, while still highlighting hopes for a better future.

8 The Museum of Failures

by Thrity Umrigar

While caring for his estranged mother in a Bombay hospital, Remy Wadia uncovers family secrets. Thrity Umrigar’s evocative novel explores the personal, political, and cultural reckonings of an immigrant son discovering compassion and forgiveness.

9 The Book of (More) Delights

by Ross Gay

Ross Gay follows up his 2019 bestseller, “The Book of Delights,” with another collection of charming essays as quirky, engaging, and wryly humorous as the first. These reflections on what makes life meaningful offer a provocative episodic read.

10 Here Begins the Dark Sea

by Meredith F. Small

Cartographers owe no small debt to Fra Mauro, a 15th-century Venetian monk who created a detailed map of the world based less on legends and hearsay, and more on the eyewitness accounts of travelers, sailors, and traders. It’s a fascinating, if overly long, exploration of the history of map-making.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Safety for fleeing Armenians

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Parts of the world are beset with conflicts over ethnic or religious differences. One conflict seems to fit that lens: the tragedy for some 120,000 ethnic Armenians fleeing an enclave in Azerbaijan after an Azerbaijani attack. Armenians are generally Christians. Azerbaijanis are largely Muslims.

Yet the forced exodus has another dynamic, one that hints at a civic future based on equality and other ideals. The refugees are fleeing toward an Armenia reaching for democratic security in a diverse European Union and away from an Azerbaijan descending into Russian-style autocracy that plays up fears of “the other.”

Once part of the Soviet Union, Armenia saw its democracy blossom in 2018 after a street revolution that brought a former journalist, Nikol Pashinyan, to power. While he has faltered as prime minister, Armenia’s civil society and news media have helped the country rise in Freedom House’s rankings of “hybrid” democracies in demanding free speech and other liberties.

Small countries caught up in ethnic or religious wars often seek the safety and strength of being a democracy in a community of democracies, where equality for all means something.

Safety for fleeing Armenians

Parts of the world are beset with conflicts over ethnic or religious differences – from Myanmar to Ethiopia to Kosovo to Yemen. One conflict seems to fit that lens: the tragedy for some 120,000 ethnic Armenians fleeing an enclave in Azerbaijan after a Sept. 19-20 Azerbaijani attack. Armenians are generally Christians. Azerbaijanis are largely Muslims.

Yet the forced exodus has another dynamic, one that hints at a civic future based on equality and other ideals. The refugees are fleeing toward an Armenia reaching for democratic security in a diverse European Union and away from an Azerbaijan descending into Russian-style autocracy that plays up fears of “the other.”

Once part of the Soviet Union, Armenia saw its democracy blossom in 2018 after a street revolution that brought a former journalist, Nikol Pashinyan, to power. While he has faltered as prime minister, Armenia’s civil society and news media have helped the country rise in Freedom House’s rankings of “hybrid” democracies in demanding free speech and other liberties.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Armenia has reduced its historical reliance on Moscow. Russians who sought exile in Armenia have helped that effort. In early 2023, the EU sent a civilian mission to Armenia to monitor the border with Azerbaijan. In September, Armenia held a joint military exercise with the United States.

“In some areas we were even ahead of some other countries who are considered to be closer to the EU,” Anna Aghadjanian, the Armenian ambassador to the EU, told Armenian News Agency. “Our serious reforms helped us ... to try and break this stereotype of Armenia not having chosen the European path.”

Since 2021, the EU has had an agreement with Armenia to support and track its democratic progress. At the same time, the EU was forced after the invasion of Ukraine to look to authoritarian Azerbaijan for natural gas to help the bloc diversify away from Russian energy. Now, with ethnic Armenians fleeing toward Armenia and reports of Azerbaijani forces killing civilians, the EU may be opening its door wider to the country. Small countries caught up in ethnic or religious wars often seek the safety and strength of being a democracy in a community of democracies, where equality for all means something.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Honored guest

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

At times it can seem like civility has left the party, so to speak. But each of us is divinely equipped to treasure and express graciousness, thoughtfulness, and patience toward one another, as this poem conveys.

Honored guest

And as ye would that men should do to you, do ye also to them likewise.

– Christ Jesus

It seems like civility slipped out in broad

daylight, leaving a shadowy, empty place

at the table – an apparent bald-faced void

seen in some uncaged remark, some

indiscriminate crossing of a line.

Yet this thought gives rise to a quiet

uprising of a winning grace within,

sparking a fresh welcome of civility in

our heart – a welling impetus to truly

esteem another’s feelings, to shield

someone’s dignity through silence, to

stifle the impulse to find fault.

This unceasing impetus – pure spiritual

goodness that flows from God, divine

Love – washes over and away the splitting

disregard of cold opinion with the truth

of our inseparability from Love.

From this spiritual reality of unity,

we – God’s children, lovely reflections

of Love’s own nature – are moved to act

thoughtfully, graciously toward each other.

The table now set within, civility softly

slips back in to break bread with us.

Viewfinder

Celebrating history-makers

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow as Peter Grier goes through the various records and emails related to the Biden impeachment inquiry and explores what’s in them.