- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 17 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Busy changing the world

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

This morning, Monitor writer Sara Miller Llana and I were comparing notes about daughters. Ours are about the same age and, like so many in their generation, have both expressed fears about climate change. But when Sara traveled the world to interview the young people most affected by climate change, she discovered something curious.

“There was not a single one paralyzed by fear of what was ahead,” she says.

They know climate could profoundly determine their futures – from hunger to child marriage. But they are busy trying to change the future. This was her takeaway from the Climate Generation series, which ends today.

“Had I not talked to them in-depth, maybe I would feel sorry for them,” Sara says. “But I learned they do not live their lives as victims.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

How Canadian villages protect their culture of cold

In the Canadian Arctic, locals speak of a “right to be cold.” How is that possible in a warming world? The work of the Indigenous Guardians is a start.

-

Melanie Stetson Freeman Staff photographer

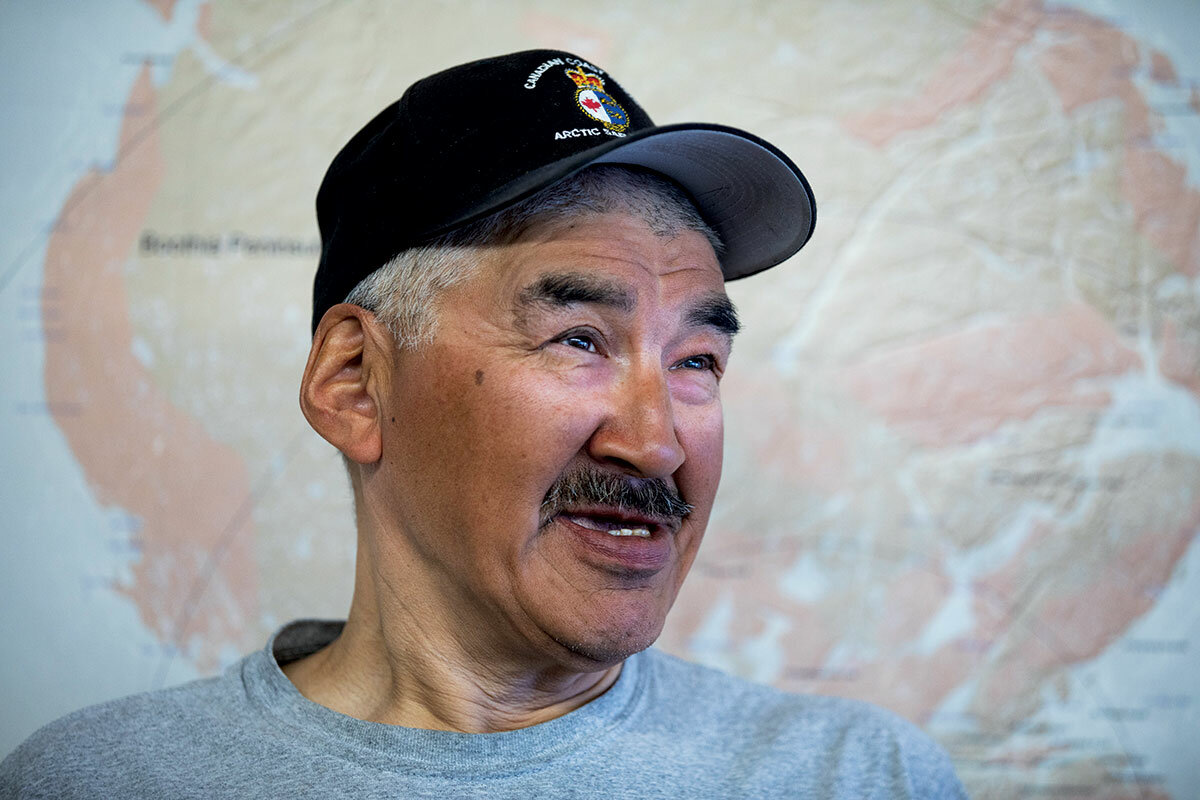

Tad Tulurialik is a “Guardian” of his fast-melting homeland.

Like most Inuit boys, he was “on the land” as soon as he could walk. He trod tundra and ice to hunt and fish so often – marking childhood not by grade but by first fox trapped, first polar bear shot – that he dropped out of high school.

In some ways, as a government-paid Guardian, the 24-year-old is doing what he’s done his whole life. But today, his knowledge and culture, once disregarded by policymakers, have become a solution for Canada and not problems to be solved.

Guided and taught by elders, he and other young Inuit born since 1989 aim to safeguard their homelands – and their cultural “right to be cold.” They’re also helping Canada achieve international conservation commitments.

The Guardians transform Western-style conservation work into something more closely resembling a traditional environmental ethos, blending science with Indigenous knowledge in a budding sustainable conservation economy.

“This is a win-win situation where the government meets the national obligations of having protected areas as part of their commitment to the international community and the Inuit continue on with their traditional ways,” says Paul Okalik, the first premier of Nunavut who now works with Canada’s World Wildlife Fund.

How Canadian villages protect their culture of cold

Masked against the Arctic glare in orange-tinted sunglasses, Tad Tulurialik is a modern conservation “Guardian” of his fast-melting homeland.

At the start of an early summer workday that never sees the sun set, he kicks his all-terrain vehicle into gear. Safe in his ancestors’ knowledge of sea currents and ice fissures, he navigates a course right off the edge of the Canadian shore onto the aqua iridescence of the frozen Arctic Ocean. He’s following older Guardians to a manmade hole in the ice shelf, a window toward understanding climate-related changes in the sea.

Even out on the ocean surface, his rifle is always swung over his shoulder. Wherever he sees a caribou or musk ox, it’s an existential given that he’ll take it. Food security isn’t found in a grocery aisle in this northernmost Canadian mainland settlement, tellingly named with the Inuktitut word for a caribou hunting blind.

In some ways, as a government-paid conservation Guardian in training, the 24-year-old Mr. Tulurialik is doing what he’s done his whole life. Like most Inuit boys, he was “on the land” as soon as he could walk. His childhood was spent on tundra and on sea and lake ice to hunt and fish with his grandparents, who raised him. His life was marked not by school grades but by first fox trapped, first polar bear shot. These were such priorities that he dropped out of high school.

That could have made him part of Canada’s persistent social inequality – Indigenous youth in some of the remotest parts of the country, undereducated, underqualified, and often losing touch with rich traditions and fleeing homelands for economic opportunity. Except today, he’s part of a solution, as a member of Canada’s Indigenous Guardians, a conservation corps working in 170 far-flung Indigenous communities.

Guided and taught by elders, he and other young Inuit born since 1989, when warming of the Arctic turned precipitous, are part of an effort to safeguard their homelands and their cultural “right to be cold.” They’re also helping Canada achieve international conservation commitments made last year, when it led a global pledge at the United Nations Biodiversity Conference in Montreal to protect 30% of its land and oceans by 2030.

For Mr. Tulurialik, who worked in construction and sewer maintenance after leaving school, a paid job as a conservationist is a dream: “I never thought I would work and get paid for what I grew up doing.”

Together, he and his Guardian colleagues are tasked with creating a sustainable future, transforming Western-style conservation work into something that more closely resembles a traditional Indigenous environmental ethos. Guardians blend science with Indigenous knowledge in a budding conservation economy dependent on the transfer of knowledge from elders to youth.

The ultimate aim of the Guardians’ work in Taloyoak is to use their sustainable Inuit practices – learned orally over millennia – to support the creation and maintenance of an Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area. The size of Maine, it is one of more than 90 in development across Indigenous Canada. Here in northern Nunavut territory, the IPCA conservation plan is led by the local hunter and trapper association; it’s nurturing an economy of land-based jobs and markets as an alternative to a future in extractive industries in a territory long eyed by mining and oil interests.

The land will be protected from development, conserving both biodiversity and a way of life based on sustainable hunting and fishing – while sequestering huge amounts of carbon, the culprit in global warming.

“This is a win-win situation where the government meets the national obligations of having protected areas as part of their commitment to the international community and the Inuit continue on with their traditional ways,” says Paul Okalik, the first premier of Nunavut who now works with Canada’s World Wildlife Fund (WWF), which is supporting Taloyoak’s efforts.

The Taloyoak team reaches its destination, having traversed shallow pools of glistening water and snow-crusted patches that have not yet acquiesced to the seasonal melt. The professional land stewards encircle the 6-foot-wide cavity descending through ice to swirling water below.

Mr. Tulurialik helps unload boxes of scientific equipment. He hands over a line of rope to help feed a net under the ice floor to gather algae and water samples. Data from the samples shapes a baseline to inform efforts to safeguard the fast-warming ecosystem.

Where 78 F is sweltering

Indigenous lands, from the Brazilian Amazon to Hawaii coastlines to Canada’s high-latitude forests, represent 20% of the globe but hold 80% of the world’s biodiversity. Inhabitants have stewarded the land for centuries. Yet in a warming climate, their homelands are in some of the most at-risk environments.

The Arctic is this nation’s – and arguably the world’s – crisis point. Here, warming is happening at up to four times the rate of the rest of the world, leading to melting permafrost, retreating glaciers, and receding sea ice. This has broad implications for the global ecosystem. Arctic ice melt slows ocean currents and makes the oceans more acidic – changes that have global implications for both climate patterns and sea habitats. Increased melting also creates what scientists call a “positive feedback loop”: As dark water replaces white snow on ice, the surfaces of the ocean and Earth absorb more sunlight rather than reflecting it. This causes even more warming.

The changes in the health of the Arctic – and the implications – are most obvious to those experiencing it day to day in the Canadian polar region. The Inuit and the wildlife they depend on here share a tightly intertwined habitat – including the summer calving ground of 50,000 Ahiak caribou and polar bear denning areas. The ocean is habitat for narwhal, beluga, and bowhead whales.

Climate change can disrupt the balance in multiple ways. Shorefast ice is a crucial platform for subsistence hunters and fishers across the Arctic, and a 2020 Brown University study shows Taloyoak faces some of the fastest rates of loss, projecting ice melt will be 44 days earlier in the spring by 2099.

Taloyoak locals have already worried about warming changing their ways. Last summer was the Northern Hemisphere’s hottest on record. The year prior, Taloyoak recorded its all-time hottest temperature of 78.8 F. Locals stayed home rather than go outside in, for them, the unbearable temperature.

Snow comes later in September; ice gets thinner, faster, in June. That, says Abel Aqqaq, lead Taloyoak Guardian, leaves the Inuit with “rotten ice.” Snow isn’t dense enough anymore to form snow houses, explains Mr. Aqqaq, who was born in an igloo some 60 years ago.

Ice melt opens more shipping routes in the Northwest Passage just above the Aviqtuuq Peninsula, where Taloyaok is perched. And that brings more human threats to the habitat balance. Extractive industries see iron ore, gold, diamonds, and oil and gas potential at the top of the world.

Climate change for the Inuit is “emphatically” a cultural issue, argues Inuit Nobel Prize nominee and activist Sheila Watt-Cloutier, author of “The Right To Be Cold.”

“Our hunting culture is dependent on a frozen North,” she writes in her book. “We Inuit simply cannot have personal freedom, we cannot have choice, if we don’t have the right to be cold, if our homeland and culture are destroyed by climate change.”

The eight paid Guardians of Taloyoak, who are all men in a society organized by traditional gender roles, include four youth in training who are in their late teens and early 20s. Together they have set out to understand the changes here.

They can’t stop the warming, but along with their Guardian counterparts across nearly 200 Indigenous communities, they are recognized and empowered by the government as the “eyes and ears” of land and ocean conservation.

Canada holds a third of the world’s boreal forests, a quarter of the world’s wetlands, and a fifth of the world’s fresh water, says Valérie Courtois, executive director of the Indigenous Leadership initiative.“It is of global importance that Canada expresses its leadership on environmental issues. And if Canada can figure it out, then maybe other parts of the world can figure it out, too.”

In that sense, she notes, with Guardians on the front lines of Canada’s fast-changing environment, the globe is dependent on the link they form in climate crisis response.

It represents a fundamental shift toward an Indigenous understanding of preservation – one that conceptualizes humans, animals, land, food, and culture as one integrated system, rather than separate sectors. That’s going to be necessary as the world faces the growing impact of climate change, says an expanding global collection of policymakers, scientists, and climate advocates.

The Guardians are being given a career opportunity with a strong future: Their work is the backbone of IPCAs and other Indigenous conservation efforts, which received $800 million (Canadian; U.S.$590 million) in funding during COP15 in Montreal last December.

David Orr, distinguished professor emeritus of environmental studies and politics at Oberlin College in Ohio, has been behind a U.S. effort to build dialogue about the connections between political systems and climate. “We’ve tended to do things in silos ... by departments and divisions,” he says. “But that’s not how the Earth works.”

Nor is it how the Inuit live.

Creating a conservation economy

The youth Guardians, part of what we are calling the Climate Generation, don’t label their work “conservation.” It’s a seamless expression and extension of their endangered lifestyle more than it is a conscious solidarity with the global climate movement.

Spread among 25 settlements across the Nunavut territory – a fifth of Canada’s landmass – the Inuit have an intimate connection to their homeland and a disconnection from the rest of the world that can’t be overstated.

An outsider visiting Taloyoak hamlet, above the Arctic Circle, might experience a sense of being trapped by its remoteness and insularity. There are no roads in or out – the nearest settlement is 85 miles away on an island. There are two grocery providers stocked with food that is sea-lifted annually from the south – but hunting is the main source of protein. There is a school, a hockey arena, and a basic hotel, but few other places to gather.

The town of 1,100 is composed mainly of 250 mostly government-subsidized houses that curl around the bay, some painted bright orange and purple. Ninety percent don’t own a house here – though many have built their own remote seasonal hunting cabins. “Home” here is less about the physical dwelling and the settlement than about the land itself.

It’s not surprising that members of Mr. Tulurialik’s generation here have never heard of the youth climate activist Greta Thunberg from another Arctic nation, Sweden. But caring for the land and wildlife – particularly caribou, which they call tuktu – is simply a part of their Inuit identity.

Summer days are a favorite time of year, not because it’s relatively warmer but because there is 24-hour sun. Entire families drive quads deep into the land at all hours of day and night, using every bit of daylight to catch arctic char and trout and dry it for the dark winter months ahead. They sleep when tired and eat when hungry.

On the summer solstice, a national holiday honoring Indigenous peoples, youth Guardian Hunter Lyall doesn’t rustle from bed until close to 5 p.m. At his home overlooking the bay, his lawn is an unselfconscious workplace full of all manner of engines, tools, and carcasses of hunted animals.

Although he and his friends spend most of their free time hunting, Mr. Lyall has an engineer’s curiosity about constructing and deconstructing – and the highlight and pride of his three years as a youth Guardian has been building a 16-foot rosewood cargo sled from scratch.

But he, like Mr. Tulurialik, also dropped out of high school – the lessons in animals’ names or geography felt pointless compared with hunting those animals and tracking that land. It’s practical know-how needed to feed the community here in Nunavut, Canada’s newest territory.

The Inuit-governed territory was founded in 1999 and was considered a capstone of Indigenous resurgence. But it suffers from legacies of colonization that forced nomadic hunter-gatherers into permanent settlements, rendering them dependent on a wage economy and the government. During the Cold War, Inuit communities were driven into the High Arctic to assert Canadian sovereignty. The government slaughtered their sled dogs and sent their children to residential schools. Today, the territory has Canada’s highest poverty rate (30%) and lowest high school graduation rate (57%).

As they do anywhere, young people with big dreams do leave. But leaving isn’t as simple for the young here as it might be in small-town Ontario or Iowa. Cost of travel is prohibitive; most only board airplanes when they need to fly out for medical services. And raising families starts early here. Many of the youth Guardians, like the 19-year-old Mr. Lyall and Mr. Tulurialik, already have small children of their own, and rely on extended family to help raise them.

The pull of tradition bonds families and interests those who do stay, but it’s increasingly too expensive to pass down. Mr. Lyall’s father, Henry Lyall, taught him to hunt. And the first arctic fox the boy shot – at age 7 – is proudly mounted and displayed in his parents’ living room. But now the elder Mr. Lyall works during the week as a heavy-machine operator for the hamlet of Taloyoak, so he no longer has time to support his family from the land. His wife and daughter knit fur-lined mittens and headbands for sale – which helps pay for fuel, ATVs, guns, and bullets.

Though the elder Mr. Lyall wasn’t pleased when his son quit school, he says the Guardian program has created a path forward: “This is good for him, that he’s got other elder guys to look up to and show him what goes on. And you know, the climate is changing so the ice conditions are getting more dangerous. So they gotta be taught.”

“I’m very proud of him. It’s who we are, and what we need to grow,” adds his mother, Viola, who posted proudly on Facebook about his first beluga whale, harpooned with the Guardians in August. “This is the way we choose to live our lives.”

That choice – to create a viable conservation economy here – makes them valuable to Canada and the world.

Guardians help “re-identify” Indigenous culture

Choice among Indigenous peoples isn’t monolithic, of course. There are debates about responses to climate change, pitting the pure economic value of extractive development against the modest sustainable subsistence tradition. In Nunavut, four mines currently extract iron ore and gold. For decades they’ve provided thousands of paying jobs, injecting cash – and environmental disruption – into some Inuit communities that depend on a healthy habitat for subsistence hunting.

“I don’t want [development] to affect my land or where it’s populated with wildlife. That’s going to affect hunting for generations,” says Mr. Tulurialik. “I want the land to be as natural as possible for my kids and their kids.”

And that’s where the IPCA – and a conservation economy – come in as an alternative to extractive industries and as a future for him and his children.

The old Western model of conservation, alone, won’t work unless it includes a vision from the people, maintains Canada’s

WWF, which provides organizational and administrative support to Taloyoak’s IPCA. Well-paid jobs in conservation can compete with the shift work at mines that takes residents away from their communities for long periods of time or to the south, says Brandon Laforest, WWF Arctic specialist. “They are land stewards. And they deserve compensation to do this conservation,” Mr. Laforest says.

Salaries are paid by various federal supports and grants. Along with a patchwork of other funding, the Guardians of Taloyoak have received $3.53 million (Canadian; U.S.$2.4 million) from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans to monitor the marine environment, create small-scale fisheries for commercial sale, and outfit camps for tourism.

These are the kinds of jobs that Inuit societies need, says Corrine Boisvert, a kindergarten teacher at the local school: “They are more along the reality of our lives, because any other job is something that was brought, like a false economy. This is a hunting and harvesting lifestyle. That’s self-sustaining here. It’s not, ‘Oh, I might not have this job next week because the co-op’s closing.’”

At the heart of it is food – and the provision of meat – which is central to Inuit survival and kinship. The local hunters, who distribute their catches to those in need from the community’s shared freezer, won a $451,000 prize for a project called Niqihaqut, or “our food.” It would ensure support for the Guardians’ sustainable production of hunted and land-gathered “country food” for commercial sale – with plans for a cut-and-dry facility that would create new jobs.

The cultural resurgence inherent in Guardians’ work makes it much more sustainable than an adherence to climate goals alone, argues Ms. Courtois of the Indigenous Leadership Initiative. The Guardians, she suggests, are a “force of re-identification” for Indigenous peoples – their knowledge and culture, once disregarded by policymakers, becomes a solution for Canada, and not a problem to be solved.

“Two-eyed seeing”

The Guardian model is based on a constant transfer of knowledge – from Indigenous to non-Indigenous and from older to younger – that in many First Nations is called “two-eyed seeing.” In Inuit culture, it is based on the incorporation of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, or traditional values, into some of the most cutting-edge science in the north.

This melding of old and new creates expansive opportunities for young Guardians Tulurialik and Lyall.

Maybe in spite of himself, says Mr. Tulurialik, who left science study behind, he has most enjoyed learning how to sample species or sea salinity. But it’s not a scientist’s curiosity so much as a cultural duty to keep his community safe.

The Guardians have been trained by the Canadian Coast Guard – another highlight for Mr. Tulurialik was learning how to operate a small vessel and do search and rescue. When his nephew ran out of gas far out on the tundra last year, the young Guardian put those skills into practice, calmly gathering proper supplies and equipment for the five- or six-hour search in the dark.

When the Guardians go “south,” Mr. Aqqaq says they always include a youth. Taloyoak’s Guardians chose to send Mr. Lyall to Quebec with the elder Mr. Aqqaq to learn how to use cameras to monitor the caribou.

And the technological savvy of young digital natives bolsters scientific research on new weather patterns and changes that have upended ancestral knowledge.

Mr. Aqqaq, sitting on an ATV on a frozen lake, wags his fingers in a typing gesture: The young Guardians, he says, “have got more knowledge on electronic gadgets” than the elders. Indeed, as Mr. Aqqaq was trying to put his finger on the name of the lake he’s always fished from, Mr. Lyall literally puts his finger on it – via Siku, a GPS app that identifies traditional place names and collects community monitoring of wildlife and ice conditions.

But then there are the moments when the young Guardians receive knowledge that no app or gadget can produce.

On this day, Mr. Aqqaq, who retired from the Canadian Rangers after 37 years, leads the men and boys through an expanse of sloping tundra, beige with splashes of lime-green, yellow, and orange lichen clinging to rocks.

They stop to search the tundra for snow goose eggs before arriving at the lake, where the edges have started to melt and natural fishing holes form, leaving an ice sheet that at points is as sharp as lava rock. A current gently chimes as it runs through the ice edge. Guided by a gentleness and patience that belies the brute survival skills these men possess, the transfer of knowledge is quiet and determined.

Mr. Lyall lays a tattered tarp on the ice. He pulls out a fishing rod made out of old hockey sticks with bits of white plastic bag as bait, and lies on his stomach, flicking his wrist until he catches a silvery arctic char the length of his forearm. But Mr. Aqqaq, guided by experience, then leads them to a different part of the lake where trout and char are more bountiful. Mr. Lyall readily absorbs that information.

“When they talk about things like birds, I listen. When they talk in Inuktitut, I listen. I want to learn it, too,” he says of his elders’ use of their Inuit language. “They know a lot, and they’ve experienced a lot of things I haven’t experienced. I look up to them because that’s where we learn.”

When several ATVs get stuck in the mud, no one reacts in frustration. They just pull each other out. Out on the ocean, when the group realizes that not all the testing equipment was brought, blame is not cast. Two just make the 90-

minute round trip to get it – while the others pull out jerky and thermoses of coffee.

Later, as Guardians collect water samples, Steve Ukuqtunnuaq, a senior Guardian and team mechanic, hands an augur to 18-year-old Guardian Roger Ullikatalik and asks so quietly it’s hard to hear: “Do you want to give it a try?”

He teaches the high schooler how to take an ice sample, slicing a piece off the 3-foot cylinder they’ve pulled out.

It might be the smallest effort amid a vast challenge, but it’s part of a much bigger movement across Canada, says Stephanie Thorassie, executive director of the Seal River Watershed initiative, which is working to create its own 20,000-square-mile IPCA that abuts Hudson Bay.

“What we’ve been really trying to do is ... give youth exposure to other careers and opportunities for them to see that they can make careers for themselves as land users,” she says. “It’s those youth that are coming up that are going to be the ones who really are caring for the land and demanding our society really take ownership and really be held accountable and take responsibility.”

Staff writer Stephanie Hanes contributed to this article.

Pricey holiday sweets? Why sugar outpaces grocery inflation.

Even as food inflation slows, sugar prices are still rising. Should the government continue heavily subsidizing sugar farmers even as customers pay more? It’s a question of fairness.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

With five trucks and a tractor to his left and a sea of leafy green before him, Dean Haubenstricker lines up his harvester and starts it forward. The high-tech machine digs up brown sugar beets, lops off their tops, and conveys them to an onboard storage bin.

This harvest, Mr. Haubenstricker’s 41st, might be his best ever. “The combination of having a little better sugar in the beets and the price outlook looks very good,” he says.

But what looks great from America’s sugar beet fields seems far less positive in the nation’s grocery aisles. At a time when overall food inflation is decelerating, sugar prices continue to rise at a stubbornly high rate. That’s helping to boost the price of sweets – from Christmas chocolates to Girl Scout cookies – and many other foods that use sweeteners. And it’s focusing a harsh light on a federal sugar program that Congress has to reauthorize as part of an overall farm bill.

A key issue is fairness. How far should the federal government go to support farmers’ income if that causes consumers to pay more for food? Meanwhile, a global squeeze in sugar supplies is pushing prices even higher at a time when consumers and voters are especially sensitive about food inflation.

Pricey holiday sweets? Why sugar outpaces grocery inflation.

With five trucks and a tractor to his left and a sea of leafy green before him, Dean Haubenstricker lines up his harvester and starts it forward. The high-tech machine digs up brown sugar beets, lops off their tops, and conveys them to an onboard storage bin.

Mr. Haubenstricker’s son Josh arrives alongside with the tractor and a trailer, allowing his father to discharge his beets even as he continues to harvest, and then shuttles them to a waiting truck, which whisks them off to storage. It’s as elegant and efficient a harvest as one will see in American industrial agriculture.

And this harvest, Mr. Haubenstricker’s 41st, might be his best ever. “The combination of having a little better sugar in the beets and the price outlook looks very good,” he says.

But what looks great from America’s sugar beet fields seems far less positive in the nation’s grocery aisles. At a time when overall food inflation is decelerating, sugar prices continue to rise at a stubbornly high rate. That’s helping to boost the price of sweets – from Christmas chocolates to Girl Scout cookies – and many other foods that use sweeteners. And it’s focusing a harsh light on a federal sugar program that Congress has to reauthorize as part of an overall farm bill.

A key issue is fairness. How far should the federal government go to support farmers’ income if that causes consumers to pay more for food? That tension, inherent in many commodity programs, runs especially high in the sugar program, which goes to great lengths to protect farmers by keeping prices above world market levels. A global squeeze in sugar supplies is pushing prices even higher at a time when consumers and voters are especially sensitive about food inflation.

“There’s a lot of fresh thinking and perspective on this that comes with the inflationary environment,” says Grant Colvin, executive director of the Alliance for Fair Sugar Policy, a broad coalition of industrial and family-owned sugar-using companies and other groups opposed to the sugar program. “But really, what I think captured the imagination of a lot of folks is the unique supply challenges that we’re facing now.”

Tight global market

The tightness in sugar supplies is global. Dryness in key exporting nations has cut into world stocks and caused sugar prices to soar. While some developing nations are having to do without, rich nations, including the United States, are paying more for the sweetener.

When prices for U.S. sugar and substitutes soared more than 11% last year, complaints were muted because prices for all food at home (groceries) rose at a nearly identical rate. But now prices for sugar and sweets (a slightly different category) are expected to jump another 9%, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, even as overall inflation at the grocery store has slowed to less than half of last year’s level.

Those price increases make the sugar program stand out – and not in a good way. Unlike most major commodity programs, which rely on taxpayer-financed insurance and other measures to protect farmers from bad years or plummeting prices, the sugar program hits consumer pocketbooks directly.

An October report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) cites studies suggesting the program costs consumers $2.5 billion to $3.5 billion per year in higher prices. That inflation doesn’t just show up in 4-pound bags of sugar on the grocery shelf. “It’s also peanut butter and cereal, and it’s salad dressing and tomato sauce,” says Mr. Colvin of the Alliance for Fair Sugar Policy.

The program does benefit farmers to the tune of $1.4 billion to $2.7 billion per year, the GAO found. But that’s still a net cost of about $1 billion a year to the U.S. economy. The GAO mentions other studies that show high prices cause job loss in American industries. Confectioners, for example, last year had to contend with prices that were twice the world price for sugar.

In previous reauthorizations of the farm bill, sugar-using companies have tried to kill the sugar program because it strictly limits how much each sugar farmer can produce and how much each sugar-producing nation can sell into the U.S. market. But ditching it completely would put American farmers like Mr. Haubenstricker at the mercy of a global marketplace where many developing nations can produce sugar for less and many industrialized nations also protect their sugar producers.

Farmers got a taste of that marketplace after 2008 when Mexico, under the North American Free Trade Agreement, won the right to sell unlimited amounts of sugar into the U.S. Over the next six years, Mexican sugar flooded in and prices eventually swooned. The premium that American beet and cane farmers had enjoyed over the world market for raw sugar narrowed from an average 11.7 cents a pound to 8.4 cents, according to the GAO.

By 2013, Mexican imports “sunk our price and drove the Hawaiian [sugar cane] industry and a lot of other people out of business,” Rob Johansson, director of economics and policy analysis at the American Sugar Alliance, wrote in an emailed statement.

A year later, Mexico agreed to limit its sugar exports to the U.S. in return for set prices on that sugar. American sugar farmers’ premium over world market prices snapped back and reached new highs, averaging more than 13 cents a pound – nearly 90% higher than world sugar prices, the GAO found.

A push for smaller reforms

This time, sugar users are pushing for smaller changes that would bring imports in line with current trade patterns and make them more timely.

“We’re not talking about major reform of the program,” says Rick Pasco, president of the Sweetener Users Association in Washington. “Should we have reforms, they would be modest reforms.”

At this stage, sugar producers and refiners aren’t showing much flexibility. “They are just trying to weaken the sugar program so that more sugar is brought in than is needed,” Mr. Johansson of the sugar alliance wrote.

It will be up to Congress to decide the fairest way forward. Lawmakers punted the farm bill to next fall, and the sugar program amounts to just a teaspoonful in this massive bill. When Congress does focus on sugar, the outcome is more likely to fall along regional, rather than party, lines – and the push for smaller changes by sugar and sweetener users may open the door to compromise.

‘My second home.’ Music school helps asylum-seeker hit a rhythm.

We’re trying something different with this story about a Venezuelan conductor who has found purpose teaching at a music school in Denver. The author, Sarah Matusek, has done a full read of the article for audio. Please click through to the deep read to find it.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

A few dozen children in Denver settle into seats, violins and violas in hand. With short cropped hair and a focused gaze, Nixon Garcia observes from off to one side.

This is a fall show-and-tell for parents at El Sistema Colorado, a free music school that prioritizes kids from low-income families. The Denver program was inspired by the original El Sistema in Venezuela, which since its founding in 1975 has sparked similar projects around the world.

With flicks of his wrists, the 22-year-old Mr. Garcia conjures up simple songs that he learned as a boy in Venezuela. He’s brought that same sheet music to students in the United States, along with hopes for asylum. Working at the Colorado program, he’s come full circle.

“El Sistema has been my second home throughout my whole life,” says Mr. Garcia.

The teaching artist is a “positive light” at the music school, says Ingrid Larragoity-Martin, executive director of El Sistema Colorado. “He’s passionate about kids, and he knows how to work with them.”

Mr. Garcia came to the U.S. in 2022 to escape violence at home, he says, including three kidnapping attempts. He’s received work authorization, allowing him to work legally while his asylum case moves forward.

‘My second home.’ Music school helps asylum-seeker hit a rhythm.

Listen to the full story, read by the author

A few dozen children in Denver settle into seats, violins and violas in hand. With short cropped hair and a focused gaze, Nixon Garcia observes from off to one side.

“Awesome,” the teacher murmurs at the sound of tuning strings.

This is a fall show-and-tell for parents at El Sistema Colorado, a free music school that prioritizes kids from low-income families. The Denver program was inspired by the original El Sistema in Venezuela, which since its founding in 1975 has sparked similar projects around the world.

“I feel really proud of them,” Mr. Garcia says of his orchestra.

With flutters of his hands and flicks of his wrists, the 22-year-old conjures up simple songs that he learned as a boy in the Venezuelan program. He’s brought that same sheet music to students in the United States, along with hopes for asylum. Working as a teaching artist at the Colorado program, he’s come full circle.

“El Sistema has been my second home throughout my whole life,” says Mr. Garcia, who teaches in Spanish and English.

The original program’s catchphrase, “tocar y luchar” – or “play and fight” in English – has evolved into a personal mantra of perseverance for the young conductor who can’t imagine returning home.

By the time he left Venezuela, in 2022, says Mr. Garcia, he’d been kidnapped three times.

Love of country

Backdropped by mountains in northwest Venezuela, the town of La Fría sits near the Colombian border. Mr. Garcia’s family, who ran a poultry farm there, enrolled their son in the popular music program at a young age.

In La Fría, says Mr. Garcia, “if you don’t play soccer, you probably play music.”

At age 5, he began learning the Venezuelan cuatro, which has four strings. Later on came the clarinet. As a teenager, Mr. Garcia began teaching other El Sistema students – a key mentorship feature of the program – and developed a love of conducting. But basic needs were stark; some students he taught sat on the floor, because there weren’t enough chairs. And beyond the solace of class, violence lurked.

When he was a young teenager, in 2015, a criminal group, called a colectivo, kidnapped him and his family at a gas station. The group held them for several hours, his family says, and demanded thousands of dollars for their release.

Venezuela, meanwhile, devolved into further economic, political, and human rights crises under President Nicolás Maduro, causing millions to flee. Mr. Garcia began attending pro-democracy protests in his El Sistema jacket, emblazoned with the stripes of the country’s flag. Inspired by a young violinist – an El Sistema alum who went viral for playing at protests – Mr. Garcia took to the streets with his own cuatro, singing the national anthem.

“You can see how everything is terrible. But in the end, you still love your country,” he says. “You don’t want to leave.”

He continued to teach and conduct, and helped prepare Venezuela to win the title of the Guinness World Record’s largest orchestra in 2021. Still, threats against his family had continued. Mr. Garcia was captured again by an insurgent group on his family farm in La Fría. Yet neither was he safe at college in another city, Mérida, where he studied engineering. A few days after appearing at a protest, Mr. Garcia says he was ordered, with a gun to his head, by men in motorcycle helmets to get into a car. He recalls the men stealing his phone, which he had used to take photos of the protest.

Although his family had arranged private security for him in La Fría, they decided that he had to leave.

“When you get private security, you know that you could die any day,” he says.

A tourist visa that his family had secured some years prior still hadn’t expired. That became his ticket to the U.S. last year. Yet even as he moved into his cousin’s home in Monument, Colorado, an hour south of Denver, the adjustment was isolating. Unable to speak English at first, Mr. Garcia recalls wondering at two hospitals – where he went for what felt like panic attacks – if he would die, as staff failed to understand him.

A family member suggested he retreat to nature, take a moment to breathe. A prayerful hike in the nearby mountains, Mr. Garcia says, helped right his course.

Inspiration struck, tuning-fork clear: Why not return to music?

A Google search for nearby orchestras yielded a name he knew.

The young conductor, in awe, reached out to El Sistema Colorado.

From volunteer to teaching artist

On a recent Friday evening, at orchestra rehearsal, Mr. Garcia introduces students to his new arrangement of “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.”

Let’s try playing it softer, he says, “like drops of water.”

The children do play it soft. Shy, even. They repeat the pizzicato – plucking their strings – and the sound swells like soft rain.

Mr. Garcia started out as a volunteer at El Sistema Colorado before the federal government issued the asylum-seeker his work authorization. That allows him to work legally while his asylum case moves forward. Now paid, he teaches groups of strings-learning students in an orchestra group called Allegro.

The teaching artist is a “positive light,” at the music school, says Ingrid Larragoity-Martin, executive director of El Sistema Colorado. “He’s passionate about kids, and he knows how to work with them.” She says other students at the music school, from Venezuela and beyond, had participated in El Sistema programs prior to coming here.

Staying behind after class, Mr. Garcia switches to Spanish to coach a cellist to whom he assigned a solo. He says he’d meant to add a flourish, a glissando, before printing out the page. As she practices, he taps along the measures with a pencil, coaxing out the melody he’d heard in his head.

Mr. Garcia’s parents, meanwhile, encourage him from a neighboring state. Also asylum-seekers, they’ve settled in Utah and speak with their son every day.

We hope that he “continues to develop in his musical world, and becomes the orchestra director that he's always dreamed of being,” says his father, Gilbert Garcia, in Spanish.

Active rest

The conductor hikes the next day, a trail near Monument, where his epiphany emerged months before. The woods here have a rhythm of their own.

Crosshatches of dry pine needles crunch underfoot. A bird calls out above. He skips a rock across a lake that laps a grassy bank.

In Venezuela, Mr. Garcia explains on the trail, music students had a quirky way to count sixteenth notes aloud – a way to practice steady, rapid beats.

“Ca-ra-o-ta, ca-ra-o-ta, ca-ra-o-ta,” he says to demonstrate. (In Spanish, caraota means “bean.”)

With students in Denver, he continues the tradition – with a local twist.

“Co-lo-ra-do, Co-lo-ra-do, Co-lo-ra-do,” is what they say now.

To the teacher, the state’s begun to feel like home. He dreams of coordinating a performance between El Sistema students in Venezuela and his own pupils here.

Meanwhile, he awaits the outcome of his asylum application, which may take years. Mr. Garcia says he wants to “work, make a life, and try to share as many things as we can from our country.”

Though he feels less anxiety these days, he says, sometimes it tries to sneak back in. When that happens, he takes a beat to remember all the good he has.

“You have the orchestra,” he tells himself.

His hands are famous. So are his printing skills.

In a time of computers, what can someone do with centuries-old letterpress machines? Some pretty innovative work, actually.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Jennifer Wolcott Contributor

-

Melanie Stetson Freeman Staff photographer

Visitors to David Wolfe’s printing shop in Portland, Maine, can’t miss the shiny Civil War-era Tufts hand-press machine that stands tall near the front door. It exited that same door several years ago, headed for a movie set.

For its cameo in the 2019 film, his “‘Little Women’ machine,” as he calls it, was hauled down to Massachusetts. Mr. Wolfe accompanied it, dressed in 1860s costume for his role as the printer of Jo March’s book. Yet as he recalls, laughing, “Only my hands made the cut.”

Wolfe Editions is a place buzzing with activity. The master printmaker and fine artist treasures his many letterpress machines not only for their place in history, but also for their ability to help him craft books, prints, posters, and more. They are essential tools for daily production, ones that stand out in an ever more high-tech world.

“The computer didn’t kill my business. It made it stronger,” Mr. Wolfe says. “A finely printed book is a beautiful object and a reminder of the past when books were vital keepers of information.”

His hands are famous. So are his printing skills.

Visitors to David Wolfe’s printing shop in Portland, Maine, can’t miss the statuesque Civil War-era Tufts hand-press machine that stands tall near the front door. It exited that same door several years ago, headed for a movie set.

For its cameo in the 2019 film, his “‘Little Women’ machine,” as he calls it, was hauled down to Massachusetts. Mr. Wolfe accompanied it, dressed in 1860s costume for his role as the printer of Jo March’s book. Yet as he recalls, laughing, “Only my hands made the cut.”

Wolfe Editions is a place buzzing with activity. The master printmaker and fine artist treasures his many letterpress machines not only for their place in history, but also for their ability to help him craft exquisitely beautiful books, prints, posters, and more. They are essential tools for daily production, ones that stand out in an ever more high-tech world.

Rather than using bits and bytes, Mr. Wolfe prints just as Johannes Gutenberg did when he developed the process of letterpress printing in the 15th century to make his famous Bible: Letters are cast in lead, then locked together, inked, and pressed into paper.

“The computer didn’t kill my business. It made it stronger,” he says, noting that he’s also benefited from recent interest in the lost art of letterpress printing. “The product I make is high end, and computers took over all the other stuff. A finely printed book is a beautiful object and a reminder of the past when books were vital keepers of information.”

A man and his machines

Mr. Wolfe typically juggles several projects at once. On a recent afternoon, he has just paused production of an edition of John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men” while waiting for a shipment of handmade paper. He’s using the time instead to create designs for one son’s new canned cocktails company (his other son is a printer). He’s also teaming up with artist and friend Charlie Hewitt to design a poster commemorating the anniversary of Muhammad Ali’s fight in Lewiston, Maine.

Mr. Hewitt has known Mr. Wolfe for 20 years, has collaborated with him on multiple projects, and happens to have a studio right next door. He says it’s important to the printmaker to pass down the old techniques to a new generation. “He is always training and teaching others. He is incredibly generous, remarkably skilled, and brings so much to every medium,” Mr. Hewitt adds.

A well-received exhibit at Moss Galleries – in nearby Falmouth, Maine – of Mr. Wolfe’s abstract, mixed-media works wrapped up recently. He’s already dreaming up more solo and collaborative projects, among them books with his own fine-art imagery and more “broadsides,” which are one-sided, flat sheets with both text and illustration.

“What he’s done with his new work is so courageous,” Mr. Hewitt says. “He is extremely versatile. He can work with both a 17th-century press and a 21st-century printer.”

Mr. Wolfe’s letterpress and hot-metal casting machines, about 10 in all, fill his spacious shop – a former bakery. Despite their age and frequent use, the devices appear impeccably cared for. (Some are undergoing renovations off-site.)

Each one has a story, which he delights in sharing: He acquired his beloved Monotype machine in 2005 to add to his growing business; he and his son schlepped an Italian Nebiolo cylinder-press machine cross-country from San Francisco; and there’s also the Intertype machine, which he explains revolutionized printing and the spread of information with its speed.

Not only is he passionate about his work, but it suits him. “Letterpress printing couldn’t be more tedious,” he says. “But I like tedium. I have the patience for it.”

Mr. Wolfe often works alone – to the sound of “bluegrass, jazz, reggae, classical, or the ’70s rock I grew up on,” he says.

Lately he’s been mentoring an apprentice, a student from nearby Maine College of Art & Design, who shares his taste in music and also for tedium. “I’ll ask Claire to put away the type,” he says, “and she’ll respond, ‘Oh, I love putting away type!’”

His influence is also felt beyond his shop’s doors.

During the past 11 years, Nicole Manganelli of Portland has taken many of Mr. Wolfe’s letterpress-printing workshops. “His warm and generous teaching is a huge part of why I have continued to come back,” she says. “Although I have tried other printmaking methods, letterpress printing is the one that holds my heart – and David’s mentorship is a big reason for that.”

“It’s all a collaboration”

Mr. Wolfe has taught at schools in Maine including Bowdoin College, Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, and Gould Academy. He’s also shared his expertise further afield, at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire and Penland School of Craft in North Carolina.

He most enjoys the workshop format, for its small size and short duration. “It’s more intense when you have to cover a lot in a short amount of time, and students in workshops are typically motivated and excited about learning.” He considers his students almost like partners in the printmaking process. “It’s all a collaboration,” he says. “I’m just the leader.”

Mr. Hewitt recalls a project he and Mr. Wolfe worked on together: the illuminated neon “Hopeful” sign mounted in 2019 on the roof of Speedwell Projects, a nonprofit gallery in Portland. “I wanted to use the word ‘Hopeful,’ and I scribbled it on paper for David,” he explains. “I needed a master printer to facilitate the process and create the font.”

Mr. Hewitt says he was elated with the design – inspired by the building’s history as an auto dealership, typeface from the badge of a 1940s Packard, and his own love for 1960s counterculture. He adds with a laugh, “If it was up to me, I might have just used Helvetica.”

For his part, Mr. Wolfe relishes collaborations like that one: the process of give and take, the creative energy, the mutual admiration. Or as he puts it, “I enjoy helping people realize their ideas. It broadens my scope, and artists are pushing the mediums beyond what they were using before. So that’s always exciting to me.”

After 40 years, he’s content to have arrived at a place in his career where he’s teaming up with a variety of artists whose work he finds inspiring and engaging. He’s also glad to be creating more of his own original designs. One way or the other, he says with a smile, “I make art every day.”

In Pictures

Finding home in a stark land

Life in the Canadian Arctic is decidedly hard. But our reporting team found that it is made easier by the spirit of community and shared purpose embraced by Indigenous villagers.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

Sara Miller Llana Staff writer

When we arrived in Taloyoak in the Arctic, a Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer told us he’s been based in almost all of the communities of Nunavut, Canada’s newest territory. And he didn’t hesitate at all to tell us Taloyoak was the nicest.

What that really meant was revealed over the next several days. We were invited to a community cookout. And when we were out on the land, we bore witness to that kindness. Every move made, every decision taken, was one based on the best for the whole.

Harsh climates create a need for community for survival. As a visitor to this village, I was privileged to experience it.

Expand this story to view the full photo essay.

Finding home in a stark land

When we arrived in Taloyoak in the Arctic, the northernmost community in mainland Canada, it was obvious that photographer Melanie Stetson Freeman and I were outsiders. It’s a tiny town where, in the summer, you get around on foot or by all-terrain vehicle, so we stood out as we went back and forth to interviews.

A Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer approached us the first morning on our way to the hunters and trappers association, whose work we are featuring as part of our Climate Generation series. Mark Flannagan, the officer, told us he’s been based in almost all of the communities of Nunavut, Canada’s newest territory, and he didn’t hesitate at all to tell us Taloyoak was the nicest.

What that really meant was revealed over the next several days. On National Indigenous Peoples Day, June 21, we were invited to a community cookout. As we arrived, two local hunters pulled up with the caribou they shot the night before, tied to the back of their ATV. They weren’t sharing the meat just because it was a special occasion – the Inuit hunters always share what they harvest. It’s all kept in a giant walk-in community freezer and handed out to those in need.

A big part of the afternoon was a game for the community elders, where shovel handles were turned into golf clubs and the players took turns trying to hit a target – at least those who could stop laughing at their faulty attempts. Elders here are fiercely loved, cared for, and listened to.

Beyond this event, it was at times hard to get a sense of community here because at the summer solstice, the sun never goes down. That means the community is out on the land, fishing and hunting at midnight, and heading home at 9 a.m. to sleep during the day.

But when we were out on the land with the Indigenous Guardians, conservationist hunters who are at the centerpiece of our project story, we bore witness to that kindness, where every move made, every decision taken, was one based on the best for the whole.

At one point, we were out on the surface of the frozen Arctic Ocean, and someone – no one ever pointed a finger – forgot some essential equipment, so two had to return for it, creating a 90-minute delay. There was no anger. In fact, no one seemed to react (except me, inwardly!). I had read a bit about Inuit parenting before arriving here – about how their society doesn’t condone yelling at children. I thought about it then.

Harsh climates create a need for community for survival. As a visitor to this village, I was privileged to experience it.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Reshaping a region with trust

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In Argentina, a new president who promised radical disruption on the campaign trail has taken a more cautious, centrist approach as he starts to govern. In Chile, citizens demanding a new constitution last night rejected the second attempt at drafting one. And in Guatemala, an anti-corruption president-elect is locked in battle with judges and prosecutors trying to block him from taking office next month.

The transitions unfolding from one Latin American country to the next tell different stories – of the moderating effect of democracy, for instance, or the pursuit of healing and reconciliation from harmful pasts. Yet together they weave a more singular narrative of a region restoring trust through civic values.

“Surveys on Latin American youth tell us that many don’t believe in political parties, they don’t believe in political institutions,” Carolina Jiménez Sandoval, president of the Washington Office on Latin America, told El País recently. “But they believe in political participation, which is something entirely different. They, as agents of change, can influence the future of their own stories and the issues that matter to them: the environment, gender equality, etc.”

Latin Americans are shaping a new era of democracy through engaged skepticism, building trust and equality through self-government and common good.

Reshaping a region with trust

In Argentina, a new president who promised radical disruption on the campaign trail has taken a more cautious, centrist approach as he starts to govern. In Chile, citizens demanding a new constitution last night rejected the second attempt at drafting one. And in Guatemala, an anti-corruption president-elect is locked in battle with judges and prosecutors trying to block him from taking office next month.

The transitions unfolding from one Latin American country to the next tell different stories – of the moderating effect of democracy, for instance, or the pursuit of healing and reconciliation from harmful pasts. Yet together they weave a more singular narrative of a region restoring trust through civic values.

“Surveys on Latin American youth tell us that many don’t believe in political parties, they don’t believe in political institutions,” Carolina Jiménez Sandoval, president of the Washington Office on Latin America, told El País recently. “But they believe in political participation, which is something entirely different. They, as agents of change, can influence the future of their own stories and the issues that matter to them: the environment, gender equality, etc.”

Voting is the most obvious form of political participation. In Latin America, however, where casting ballots is mandatory in most countries, it is not the most reliable measure of citizen confidence. The latest survey by Latinobarómetro found that only 48% of people in the region support democracy – down from 63% in 2010.

But several trends point to the growing strength and influence of civil society across Latin America. Younger citizens, women, and Indigenous groups are behind gains in equality, access to justice, and the election of candidates promising to boost economic opportunity by rooting out corruption.

That activism underscores one way that trust is built through democratic participation. In countries with low levels of public trust in government and political parties, the World Bank notes, citizens develop more robust forms of social capital to seek change. That explains Chileans’ strong desire for a new constitution yet rejection of drafts that tilted too far in one political direction or the other.

It may also be a reason for President Javier Milei’s more cautious start in Argentina. Since taking office on Dec. 10, he has backed off his more controversial proposals, like shutting down the Central Bank, and appointed experienced centrists to stabilize an economy in crisis.

As Patricio Navia wrote in Americas Quarterly, Mr. Milei may be taking a note from Chile and Colombia, where incoming presidents faced quick public backlash for seeking change too quickly. Argentines elected Mr. Milei “not because they truly believed in his economic program but because they thought the incumbent status quo was untenable,” wrote Dr. Navia, a political science professor at Diego Portales University in Chile.

“Overall, democratic processes and institutions are shifting towards higher citizen engagement and civil society inputs are increasingly being taken into consideration,” said Julia Keutgen, program manager at International IDEA. The effect of increased civic participation is a cultural shift in democratic institutions, she wrote in a blog post for Institut Montaigne, “one that favors transparency and openness and acknowledges the relevance of public opinion.”

Latin Americans are shaping a new era of democracy through engaged skepticism, building trust and equality through self-government and common good.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

What makes prayer effective?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Lyn Price

Prayer that’s based on the spiritual facts of being opens us to healing.

What makes prayer effective?

A conversation I had some years ago made me realize that I had been healed of the symptoms of panic attacks over 30 years ago. Until then, I had completely forgotten about them. At the time, those symptoms had been aggressive to the point where I sometimes had to leave work early.

Over the course of several months, I called a Christian Science practitioner many times for treatment through prayer. She often reminded me that I was relying on a Science that could be proved. The attacks became less frequent, and eventually just faded away and were forgotten.

How was this accomplished? What is it that makes such prayer effective?

Jesus’ disciples saw that his prayers healed people. They wanted their prayers to be effective as well. So they asked him to teach them how to pray, and he gave them the Lord’s Prayer. The Christian Science textbook, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, calls it “that prayer which covers all human needs” (p. 16).

It is not the words of a prayer that heal, but an understanding, a knowing, of the spiritual truth behind the words. Mrs. Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, found that the spiritual significance of the Bible makes prayer based on the Bible’s teachings effective.

She said, “Take away the spiritual signification of Scripture, and that compilation can do no more for mortals than can moonbeams to melt a river of ice” (Science and Health, p. 241). And regarding her ill health in her youth, “...she learned that her own prayers failed to heal her as did the prayers of her devout parents and the church; but when the spiritual sense of the creed was discerned in the Science of Christianity, this spiritual sense was a present help” (Science and Health, p. 351).

So what is the spiritual significance of the Lord’s Prayer?

Science and Health includes a line-by-line spiritual interpretation of the prayer (see pp. 16-17), but here are a few notable points. First, it starts and ends with God. After focusing our attention on God, “Our Father,” and on the facts of God’s harmony, oneness, power, presence, and supremacy, the prayer proceeds to petition. This part of the prayer also requires something of us. We must accept the ideas – the inspiration or daily bread – that we are given, and we must follow this inspiration, which leads to forgiving and being forgiven and away from sin, disease, and death. The prayer closes with a final statement of God’s allness.

The words “I,” “me,” and “my” do not appear in the Lord’s Prayer. It is not about self. It is about the entire world. Jesus expected his followers to pray for the world, not just for themselves. This is echoed in the following counsel from “No and Yes” by Mrs. Eddy: “True prayer is not asking God for love; it is learning to love, and to include all mankind in one affection” (p. 39).

The effective prayer of understanding and obeying the leadings of divine Love, God, can free from any oppressive condition – anything not created or sanctioned by God, good.

The first chapter of Genesis in the Bible tells us that God created man in His own image – as “very good” – and Christian Science teaches that because God, good, is all-power, evil is powerless and can be proven so. Therefore, in prayer we must see evil as powerless and know that it cannot find a foothold in our thinking or anyone else’s.

We must pray from the standpoint of spiritual fact – that God is omnipotent Love, that we are Love’s totally loved children, and that our health and harmony cannot be lost under His loving government.

Effective prayer is heartfelt listening for and humble receptivity to what God knows and is telling us at any given moment – and willingness to follow that inspiration, even if it is not what was expected. This inspiration could be an instantaneous consciousness of the infinitude of good, or it might gradually develop through reasoning on the basis of divine law.

Either way, the result is the understanding of and faith in God that overcomes evil with good. In the case of my healing of panic attacks, it was gradual, but I’ve also had experiences of seeing an immediate change.

Prayer based on divine inspiration, our daily bread – and on following that inspiration in the way that Jesus demonstrated – is effective.

Adapted from an article published in the Sept. 27, 2021, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

Hanging out

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Tomorrow, we’ll introduce you to the Post-Evangelical Collective. These are Christians kicked out of their churches who aren’t willing to give up their faith.

And please let us know if you listened to the full audio read of the story about the Venezuelan conductor – and what you thought of it. You can reach me at editor@csmonitor.com.