- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 15 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Welcome to 2024. Here’s a small gift.

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

We’re back, and we have a small New Year’s gift. We’re adding news briefs to The Christian Science Monitor Daily. The idea is (we hope) obvious, and something many readers have said they’ve wanted. After our lead story, you’ll see a short list of today’s top news.

If you want to read the full briefs, which are taken from wire services, click on the link below the bulleted list. That takes you to our news briefs page, with all the briefs from recent days as well as links to Monitor stories that offer added depth. Please let us know what you think at editor@csmonitor.com.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Pessimism or progress: What did you see in 2023?

Perspective matters, so it’s useful to step back from the daily news flow and assess how much progress we have, or have not, made.

For most of us, 2023 was not the year we expected, or dreaded.

The year will no doubt be remembered for the grisly Hamas attack of Oct. 7 and the violence it unleashed.

But this was also the explosive first year of artificial intelligence surging into households and workplaces, hyperenergizing the race toward what may soon become one of the most powerful tools in human history – with all the existential fear and immense promise that implies.

On climate change, this was the year that China, easily the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, expanded its solar power capacity on such a historic scale as to keep prospects alive, if barely, for holding global warming within a relatively manageable 1.5 degrees Celsius.

And this was the year of the recession that never came, despite always being forecast as just a few months away.

As 2024 dawns, the world faces daunting dangers. But most of them – from climate disaster to rogue artificial intelligence – are complications arising from the enormous, sweeping progress the world has made in the human condition. As we face the hard work ahead, we can perhaps draw confidence from the great distance we’ve already traveled.

Pessimism or progress: What did you see in 2023?

In the sweep of history, what kind of a moment was 2023?

The year will no doubt be remembered for the grisly Hamas attack of Oct. 7 and the violence it unleashed.

But this was also the explosive first year of artificial intelligence surging into households and workplaces, hyperenergizing the race toward what may soon become one of the most powerful tools in human history – with all the existential fear and immense promise that implies.

On climate change, this was the year that China, easily the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, expanded its solar power capacity on such a historic scale as to keep prospects alive, if barely, for holding global warming within a relatively manageable 1.5 degrees Celsius.

This was the year that the accelerating global drop in extreme poverty – which has plunged by more than two-thirds since 2000 – resumed after its pandemic pause.

And this was the year of the recession that never came, despite always being forecast as just a few months away.

For most of us, 2023 was not the year we expected, or dreaded.

In the United States, we started the year with so little confidence in the economy that Gallup analysts called it “among the worst readings since the Great Recession.” Most Americans expected rising joblessness, high inflation, higher taxes, and a falling stock market. They weren’t crazy. In January, a Wall Street Journal survey of economists found 61% forecasting a recession for 2023.

Most Americans and all those economists, of course, were wrong.

Joblessness remains solidly in the zone that economists call “full employment,” meaning essentially that people who want a job can find one. From autoworkers to Hollywood screenwriters to hotel cleaning staff, employees have gained leverage. Even those managers who just want their now-remote workers to show up at the office a few days a week are often forced to back down. Inflation – though still above the Federal Reserve’s 2% target – is close to normal. We can’t know where the stock market will be by the time you’re reading this, but the S&P 500 neared the end of the year up more than 25%.

Yet in a recent Gallup survey, only 1 in 5 Americans gave the economy a positive rating. As markets writer Matt Phillips put it in an Axios newsletter in November, “Psychologically, America is experiencing a recession that doesn’t actually exist.”

Never have so many had so much, in relative peace and safety – and been so unsettled about it.

Why the unease? Some of the leading conjectures are these:

•The aftershocks of the pandemic: About 7 million deaths globally were attributed to COVID-19, and there were possibly as many as 20 million. It upended schooling, work patterns, and businesses, while carving new divisions over civil rights, public safety, fairness, and trust in government.

“It had a lot of knock-on effects,” says Angus Hervey, a political economist and editor of the Future Crunch newsletter. The world is still working back from them. “Globally, we’re still numb.”

•Media tribalism: People are increasingly able to curate and inhabit their own realities digitally, and that often includes a negative view of those outside their bubbles. In the hyperpartisan U.S., many media and political players make a living from riling people up – focusing on threats to their values rather than on trust-building, common ground, or progress.

•The pace of change: For many people, in many parts of the world, social change has just been too much, too fast. New attitudes toward gender, the computerizing of jobs, the shifting mixes of ethnicities and cultures through immigration – all keep unsettling the familiar and can create insecurity.

“Things are just changing too fast for people to be comfortable with,” says global opinion expert Bobby Duffy, now a professor at King’s College London.

•Rising expectations: As Zachary Karabell, a historian, investor, and founder of The Progress Network, puts it, “Never have so many people felt they have the right to be heard and lead a good life and have their needs respected.”

That, of course, is not in itself a bad thing. But it’s a yardstick by which it can be hard for reality to measure up.

As 2024 dawns, the world faces daunting dangers. But most of them – from climate disaster to rogue artificial intelligence – are complications arising from the enormous, sweeping progress the world has made in the human condition. As we face the hard work ahead, we can perhaps draw confidence from the great distance we’ve already traveled.

Here is a review of the state of progress on some major fronts.

The economy and standards of living

Global wealth is rising again after a pandemic dip. The recovery is across the board, but even stronger in poor and middle-income countries than in rich ones.

“The global economy has outperformed even our optimistic expectations in 2023,” summed up Goldman Sachs analysts in a November report.

The positive transformation of billions of lives over the past generation has been enormous and unprecedented in the history of humankind. The explosion of prosperity in China is familiar to many. But it’s a much broader story.

Bangladesh, for example, was the third-poorest country in the world 50 years ago – the flood-soaked endpoint for India’s largest rivers. It has now surpassed upwardly mobile India itself in income per capita and is projected to graduate out of the United Nations’ “least developed countries” status in the next two or three years. Economic confidence there is relatively high.

Since the turn of this century, the wealth of the world’s median family has grown fivefold. Extreme poverty – defined by the World Bank as living on less than the equivalent of $2.15 per day – was the lot of most people up to 1955. By the year 2000, it had dropped to 29.3% of the world population, and the plunge was accelerating – to 8.4% in 2019. The next year, at the height of the pandemic, the rate jogged upward for the first time in decades to 9.3%. In 2023, it headed down again to about 8.6%.

Meanwhile, the net worth of the median American family grew 37% from pre-pandemic 2019 to post-pandemic 2022, after discounting for inflation, according to Federal Reserve Bank surveys. For poorer households, the rising value of their vehicles accounted for the bulk of their assets, but still, wealth grew more for poorer and middle-income families than for richer ones.

The Unexpected Compression: Competition At Work In The Low Wage Labor Market,” National Bureau of Economic Research

Soaring post-pandemic inflation is quickly losing altitude. Thanksgiving dinner this year actually cost less than in 2022. So did a tank of gas. Wages have pulled ahead of inflation, especially for lower-income workers.

Housing is still stuck at the worst level of affordability since the Reagan years (when it was far worse). For most Americans, about two-thirds of whom are already homeowners, affordability is not a problem until they need a new mortgage. But the national median rent has risen 22.5% since the pandemic began, to about $2,000 per month. It leveled out in 2023, letting incomes catch up a bit. But about half of all renters still spend more than 30% of their income on rent.

While Americans give their economy dismal ratings, that’s not how they behave. They keep spending briskly. (When people are worried, they save.) And even as households run up credit card bills, the share that have debt in collection is at a historic low.

Americans also believe by 2 to 1 that each generation is faring worse than its parents. Here again the numbers say otherwise. Some 73% of Americans in their 40s have higher incomes than their parents did at the same age, adjusted for inflation, according to a Federal Reserve Bank of New York study. By comparison, in 1979 that figure was 57%. Similarly, University of Central Arkansas economist Jeremy Horpedahl has found that the net worth of millennials, mostly in their 30s, is about the same as it was for baby boomers at the same age. Gen Xers, in their 40s and 50s, have actually done somewhat better than the boomers at their age.

But this is all in the rearview mirror. Looking forward, 2023 was the year millions of people first used a generative AI program (such as ChatGPT), the next great platform for economic productivity. Though too soon to assess its impact, AI has the potential to become as powerful a change agent as the internal combustion engine, mass manufacturing, electricity, and computing itself, says Jason Crawford, a technology historian and founder of The Roots of Progress. “In the most extreme scenario, which I still think is pretty speculative but not impossible, it is the next big thing in human history – after agriculture and the Industrial Revolution.”

Such a powerful tool also raises civilization-scale fears about what could go wrong. But promise and peril both, this brave new world is coming fast.

Inequality in America and the world

The world has become dramatically more equal in recent decades. On measures like life expectancy at birth, average years of schooling, daily calorie intake, and access to the internet, the differences between countries have narrowed. A Cato Institute study looking at eight such quality-of-life measures found that overall inequality between countries had closed by about half in less than 30 years.

The pandemic was a setback, as it hit the economies of poor countries harder than richer ones. But the emergence from the pandemic has also been stronger in poor countries, according to a report by the Swiss bank UBS. So the longer trend is moving back toward its lifting-all-boats course.

In the U.S., on the other hand, inequality has risen significantly since the 1970s – with the concentration of wealth in the top 1% nearing the extremes of the Roaring ’20s.

But inequality appears to have topped out around the Great Recession in 2008. When taxes and government aid are figured in to get a more accurate view of actual household incomes, a Congressional Budget Office study found that the Gini index, the most common measure of income inequality, actually dropped about 5% from 2007 to 2019. And coming out of the pandemic, wage gains by lower-income workers have accelerated that trend. A 2023 National Bureau of Economic Research report found that higher pay has cut the soaring inequality that developed over the previous four decades by 38%, and in just three years.

World Bank

Earlier this year, the gap between white and Black employment rates reached a historic low. This came a few months after the gap between white and Hispanic rates also reached a historic low. A U.S. Treasury report called the recovery the “most equitable in recent history.”

Homeownership is still highly unequal between races, however. While 74.5% of white Americans own homes, only 45.5% of Black residents do. But a survey this summer of Generation Z (20-something) first-time homebuyers by the insurance-comparison website The Zebra found that 20.2% were Black, far higher than their 13.6% of the population. This may imply a greater degree of homeownership equity for this rising generation.

Most of the gains in equality both around the world and within the U.S. have come not by making the prosperous less so but by raising the incomes of the rest, especially those who are lowest paid.

Health and safety

The progress in humanity’s health in modern times has been enormous. The most sweeping and inclusive way to track overall health is through changes in life expectancy, which is based on the ages of those who have already died. In 1900, global life expectancy was 32 years. In the U.S., it was 47.3. Today, the global average is 73, many countries have averages into the 80s, and no country in the world, not even Afghanistan, has a life expectancy as low today as America’s in 1900.

The most dramatic gains in the early 20th century were in children surviving past the age of 15 and in mothers surviving childbirth. Much of the later progress has been against tropical diseases like malaria as well as smallpox and polio. It’s also due, especially in the higher-income countries, to the decline in smoking.

Then came the pandemic. It created a dip in life expectancy almost everywhere (hat tip here to no-dip Norway). But by 2022, most of the world was back on the upward path, pushing life expectancy to a new global high.

But not the U.S. American life expectancy peaked a decade ago at 78.8 years. By 2022, it had slid 2.4 years to a 20-year low. It rose again in 2023 to 77.5 years. But why the slippage?

The biggest factors have been the epidemic of opioid addiction (especially fentanyl), the rise in Alzheimer’s cases, and the spike in homicides seen in 2020 after the police murder of George Floyd and during the pandemic.

The direction at least is looking up. Opioid deaths declined slightly in 2022, but no clear trend has emerged. The number of dementia cases has risen as baby boomers age, but studies now show that in North America and Europe, the percentage of people at a given age who develop dementia has been falling about 13% per decade for the past 25 years. And the surge in homicides is fast heading back downward.

In pre-pandemic 2019, the homicide rate in the U.S. was about half the level of the early 1990s. America had become a far safer place – though still not nearly as safe as any other high-income country. The rate shot up 30% during the pandemic, then dropped 6% in 2022, and at the midpoint of 2023 was on track to drop another 7% to 10%. The latter would be the biggest one-year drop ever.

Yet a Gallup poll found that 56% of Americans thought crime had risen in 2022. In fact, over the past 24 years, majorities thought crime was higher in all but four years, while it had actually fallen in all but four of those years.

Furthermore, violence has declined while incarceration rates have moved toward greater racial equity. Black men are still imprisoned at four times the rate of white men, but the disparity used to be much higher. The Sentencing Project found that from 2001 to 2021, the share of Black men in prison fell by 48%, and white men by 27%.

Falling violent crime is a global phenomenon. But in America, there are also signs of an underlying civility growing in the shadow of rancorous political divides.

An 18-year study of California schools completed in 2023 by a team at UCLA found that in the state’s public schools, fights and weapons-carrying were down dramatically, especially among Black and Latino youth. Students report greater connection, comfort, and what the report calls “belongingness.” And beyond California, despite the fear levels driven by high-profile campus shootings, every available measurement shows American schools to be far safer than they have been in decades.

Environment

The average global temperature has already risen at least 1.2 degrees Celsius since preindustrial times. Sea level is 8 to 9 inches higher than in 1880. The 12 months through this past October were the hottest year, globally, on record. The 10 hottest-ever summers have happened since 2010.

These are signs of our climate-challenged times. But so are the following.

China expanded its solar power output so massively in 2023 as to “all but guarantee” its emissions will go down in 2024 and beyond, according to an analysis by the website Carbon Brief. The country huffs out a quarter of the world’s greenhouse gases but also accounts for about half of the world’s clean energy investment. It now looks to hit its ambitious goal of producing 1,200 gigawatts of clean energy by 2030 – five years early. And if 2023 is indeed China’s peak year for emissions, it’s arriving seven years ahead of its declared target.

In fact, the whole world is toeing the edge of peak emissions. Global emissions would have dropped in 2023 except for the widespread droughts that slowed hydropower output, according to the energy think tank Ember. Most of the countries already past peak have reduced emissions even as electricity demand has grown.

International Energy Agency

The world’s current path is toward a high-impact total temperature rise between 2.5 and 2.9 degrees Celsius by the end of this century, the latest United Nations report says. This is down from a 3-degree Celsius rise forecast in 2015. A recent International Energy Agency report says the path to holding it to a modest 1.5 degrees Celsius is “very difficult – but remains open.”

Diplomats achieved a symbolic breakthrough at the U.N. climate summit in December, where nearly 200 nations agreed for the first time to “transitioning away from fossil fuels” in a “just, orderly, and equitable manner.” It’s easier said than done, of course, but this was an important step in articulating a shared global goal.

Democracy

Americans don’t like the quality of their hyperpartisan, deeply divisive political life. And they attach high stakes to it. Majorities in both parties see their individual rights, their values, and democracy itself under attack.

The good news: Surveys still show Americans’ long-standing confidence in local government running strong.

But it falls off sharply from there. A Pew Research Center study this fall found overall trust in government at its lowest levels in nearly 70 years. For the first time ever, a majority now sees the U.S. Supreme Court unfavorably. The share that holds negative views of both political parties has risen to 28%.

Here’s an oddly hopeful note: One of Americans’ top concerns, and one of very few that show complete partisan unity, is the inability of Republicans and Democrats to work together. People still want the relationship to work.

It’s not, as yet, getting better. A Gallup study in the fall found that differences between Democrats and Republicans on each of 24 issues had either widened or stayed the same over the past decade.

But on 17 of those issues, opinion in both parties was moving in the same direction even when the gap widened. For example, Democrats are far more supportive of stricter gun laws than Republicans are, but support for such laws in both parties is higher than it was 10 years ago. Also, Republican majorities now back the legalization of marijuana and same-sex marriage, which Democrats have long favored. And Democrats have shifted slightly toward the Republican position on the unfairness of taxes, while Republicans have moved even further in that direction.

In the U.S. over the past 20 to 30 years, political affiliation has become an increasingly central, emotionally charged tribal marker. But on policy issues, says political philosophy professor Robert Talisse at Vanderbilt University, “rank-and-file citizens are no more divided than ever.”

“It’s more like being a Mets or a Yankees fan,” he adds.

For many, the concern is less the direction of change than the speed of change – cultural, demographic, climatic, and economic. On the right, it’s too far, too fast. The left feels it shouldn’t wait any longer. This is a global phenomenon.

These debates are amped up by real or perceived insecurity when people feel threatened. “There is also agency here, where media and political actors can increase this sense of tension through focusing on differences and tribal identities, in stoking a culture war,” says Dr. Duffy of King’s College.

There are better ways to have these conversations. None have yet found traction in the U.S., but so-called deliberative reform is popular in northern Europe and Canada. Ireland created its first Citizens’ Assembly in 2016, choosing 100 people at random, like a jury, to make recommendations on Ireland’s constitutional ban on abortions. The assembly heard a wide range of testimony and recommended new abortion policies, beginning with removing the ban. The referendum on the latter passed by 66.4% of the vote. Since then, four other assemblies on controversial issues have been held, and 87 of the 128 recommendations of the first four assemblies have been all or partly adopted by Irish governments.

A 2022 survey by The Irish Times found that 80% of the Irish population trusts the assemblies to make good decisions. Versions of the Irish model are being adapted in countries from Belgium to South Korea.

“People are not unwilling to look at information and consider the issues,” says Dr. Duffy. “They will listen and they will adapt.”

But we don’t see each other that way these days.

How far we’ve come

“The social fabric appears to be unravelling: civility seems like an old-fashioned habit, honesty like an optional exercise and trust like the relic of another time.”

That sentence may seem to capture the tenor of the times. But it was written 2,000 years ago in Rome. It opens a recent study by social scientists from Columbia and Harvard universities of the perception of moral decline across 60 countries over at least 70 years. Researchers found that people in every country and in every decade believed moral and ethical behavior started worsening roughly around the time they were born.

The study’s conclusion: They are “almost certainly mistaken.”

The past year has seen much tragedy in Ukraine, Israel, Gaza, Ethiopia, Yemen, and beyond. Some of the dangers ahead are potentially massive in scale. Progress, like all learning, has come in leaps and pauses and some stumbles back. But as we’ve gained ground, our expectations have moved ahead with us. As they keep rising, it’s easy to lose sight of how far we’ve come.

Marshall Ingwerson is the former editor of the Monitor and founder of The What Works Initiative.

Sidebar: Opportunity in Bangladesh

Bellal Hossain, from Bangladesh, is the first university graduate in his family. His parents, garment workers, never completed elementary school. They worked their entire lives on the factory floor, where they met and fell in love, raising three children along the way.

Three decades later, Mr. Hossain, a freelance academic writer, set up a sewing shop in the family home in Dhaka. “Since I already graduated, it is not respectful for them to be working outside the home,” he says.

Life has improved in countless other ways for the family – their prospects advancing alongside their country, which was one of the world’s poorest when it became a nation in 1971. But it is projected to graduate out of the United Nations’ “least developed countries” status in 2026.

“My parents were leading such a very poor life that they couldn’t even manage three meals a day at a period in their lives. They lacked proper clothing and housing,” says Mr. Hossain, as he gives a Facebook video tour of the family’s home, where his parents sit behind sewing tables piled high with crisp white cloth to make into school uniforms. “But we are living in a sound environment now,” he says.

During the academic year, Mr. Hossain is able to earn three times his parents’ combined income. He eventually wants to work for the government, while his two younger siblings are on track to complete university.

The family still endures hardship. They rent their home, so they are vulnerable to income loss if the rent increases or if they have to move. And the pandemic threw them into debt.

A common conversation in Bangladesh is whether progressing to middle-income status will mean a loss in foreign support that has helped buoy the nation.

“But even in my life, not comparing to my parents, Bangladesh has progressed in such a way that I have seen,” says Mr. Hossain. “Right now, if someone is very much interested in working hard, he has the opportunity.”

– Sara Miller Llana / Staff writer

Today’s news briefs

• Major Israeli Supreme Court ruling: Israel’s Supreme Court strikes down a key component of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s judicial overhaul.

• Top Hamas official killed: A founder of Hamas’ military wing is killed in an explosion in a suburb of the Lebanese capital, Beirut. News reports say the strike came from an Israeli drone.

• Harvard president resigns: Harvard University President Claudine Gay resigns amid criticism over testimony at a congressional hearing. She was unable to say unequivocally that calls on campus for the genocide of Jews would violate the school’s conduct policy.

• Nobel Prize winner sentenced to jail: A Bangladeshi court sentences Muhammad Yunus, who pioneered the concept of microloans, to six months in jail. Supporters say the government is attempting to discredit him.

• Japan earthquakes: A series of powerful earthquakes hits western Japan. Prompt public warnings appear to have kept at least some of the damage under control.

In Gaza, an added burden: Communication blackouts

In wartime Gaza, phone and internet service has been besieged. Better-equipped journalists are having to balance their professional duties with helping people cope.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Ghada Abdulfattah Special contributor

-

Taylor Luck Special correspondent

Amid the chaos, destruction, and terror of war, communication blackouts have been an extra and complicating challenge for Palestinians in Gaza. Widespread phone and internet outages have cut Gaza residents off from the outside world and each other, led ambulances to get lost, and left anxious families wondering for days whether relatives were alive or dead.

Communication blackouts have dogged Gaza since Oct. 27, as fuel shortages hit telecom provider Paltel and Israel repeatedly struck cell towers and underground networks. According to Paltel, nine enclavewide blackouts of 24 hours or longer have occurred since the start of the war. But their frequency is increasing, including a two-day outage beginning Dec. 27.

Gaza journalists, by pooling their resources, remain able to use a satellite uplink to broadcast live feeds in front of Al-Aqsa Hospital in Deir al-Balah. Elsewhere in Gaza, video, photographs, and text reports must be uploaded by phone.

One day last week, Bassem Khalaf, a veteran journalist for the Al Araby TV network, had only hours to upload his latest report. With his deadline looming, he raced to a rooftop at the edge of the Al-Aqsa complex in hopes of a signal.

“We have returned to the stone ages, but with iPhones,” he says.

In Gaza, an added burden: Communication blackouts

Signaling a new phase of its war against Hamas, Israel has ordered a drawdown of its troop deployment in the northern Gaza Strip. But there was little clarity over when the conflict might end for Gaza Palestinians increasingly left in the dark.

In a statement Monday, the Israeli army said it would begin a series of more targeted strikes against Hamas, and that the withdrawal of several brigades was meant “to gather strength for upcoming activities in the next year, as the fighting will persist.”

Yet even as it embarked on the demobilization, Israel maintained its intense bombing in central and southern Gaza Tuesday. Palestinian health officials said another 200 people were killed, pushing the death toll in Gaza past 22,000 since the war began Oct. 7 with a Hamas attack that killed more than 1,200 people in Israel.

In Deir al-Balah, in central Gaza, an estimated 60,000 residents of the nearby Bureij refugee camp filled the streets Tuesday amid bombing and artillery fire, days after fleeing their homes.

Many huddled around the Salah ad-Din traffic circle, anxiously searching for a taxi to take them to Rafah at the southern edge of the enclave, where they hoped for a better chance of finding shelter and food. Others erected makeshift tents or simply lay at the edge of the street.

Amid the chaos, destruction, and terror of war, communication blackouts have been a complicating challenge, with Gaza Palestinians increasingly facing cuts to phone and internet service. Widespread outages have cut Gaza Palestinians off from the outside world and each other, led ambulances to get lost, created food aid mix-ups, and left anxious families wondering for days whether relatives were alive or dead.

“We have returned to the stone ages, but with iPhones,” says journalist Bassem Khalaf as he scales a fire escape to capture a bar of signal.

Attacking the network

Communication blackouts have dogged Gaza since Oct. 27, as fuel shortages hit telecom provider Paltel and Israel repeatedly struck cell towers and underground networks.

According to Paltel, nine enclavewide blackouts of 24 hours or longer have occurred since the start of the war. But their frequency is increasing, including a two-day outage beginning Dec. 27.

By pooling their resources, Gaza journalists remain able to use a satellite uplink to broadcast live feeds in front of Al-Aqsa Hospital in Deir al-Balah.

Elsewhere in Gaza, video, photographs, and text reports must be uploaded by phone. With networks often down, a feature in newer smartphones enables searches for alternative nearby networks. But in Gaza this involves a search for a signal amid daily fluctuations in network strength, with locations discovered by trial and error and shared by word-of-mouth.

One day last week, Mr. Khalaf, a veteran journalist for the Doha, Qatar-based Al Araby TV network, had only hours to upload his latest report on Israel’s military offensive and the forced evacuation of the Bureij camp.

With his deadline looming, thanks to a tip from a colleague, he raced to a building at the eastern edge of the Al-Aqsa Hospital complex, darting down alleyways and over barricades in hopes of a signal.

Scaling a wobbly steel fire escape, clinging to the side of a building, Mr. Khalaf found a spot on the rooftop that had a glimmer of a signal.

He then stretched out his arm in different directions, contorting himself around water tanks, atop plastic chairs, and over the building’s edge to catch a stronger signal.

“What used to take a few minutes now takes 45 minutes to upload a three-minute video,” he says.

Acting as a rare outlet to the world during blackouts, Gaza journalists now play multiple roles for their community.

“People approach us seeking information about targeted locations, casualties, service providers, international organizations, or the names of evacuees listed at the Rafah border,” Mr. Khalaf says. “We have to balance between serving people’s needs and fulfilling our journalistic duties.”

Directing first responders

The communication outages hinder first responders in Gaza, where every additional minute – or wrong turn – could be a matter of life or death.

Unable to get messages or calls from residents in affected neighborhoods, paramedics instead listen for the explosions of mortar shells and airstrikes and race in that direction.

“When we do not receive calls from affected areas, we rely on hearing bombardments and airstrikes to determine where to send the ambulances,” says Iyad Zaqqout, director-general of the Gaza Health Ministry’s ambulance and emergency department.

That often leads to wasting scarce fuel and resources, and sometimes sending ambulances to farmlands where an errant rocket has fallen and there are no casualties in need of rescuing, he notes.

Often, during blackouts, Gaza’s first responders rely on word-of-mouth updates. “Sometimes people bring us news of strikes by donkey cart, bicycle, or on foot,” Mr. Zaqqout says.

However, that “poses a big risk as we may be sending our ambulances to where airstrikes are still ongoing,” he notes.

During a blackout last month, an ambulance on call near the European Hospital in Khan Yunis reportedly was fired upon by Israeli forces, wounding two paramedics.

Palestinians cleared to leave Gaza for lifesaving surgery or medical treatment are also impacted. With telecom outages, Gaza health officials say they often do not receive the evening list of approved names for medical transfer out of Gaza from Egyptian authorities, causing individuals cleared to leave the strip to miss the several-hour window to travel to Rafah and cross the border.

Families who would check their food aid pickup date via a United Nations Relief and Works Agency web portal now wait in line for hours at flour distribution points, asking other families to guesstimate if their turn will come that day.

Lack of communications has been a constant anxiety for Isra Al Bushi, a journalist for the Iranian Al Alam TV, whose family home is located in a Deir al-Balah neighborhood that has frequently been hit by Israeli shelling and airstrikes during the past month.

Last month she learned an airstrike hit her neighborhood while on-air in front of Al-Aqsa Hospital, but with networks down had no way of checking on her children.

She found herself torn between focusing on the camera and anxiously glancing at an arriving ambulance to see if her sons and daughters were among the wounded or dead.

“I finally threw the microphone down and went to search for my children among the dead,” she says. “They were unharmed, but my heart broke for the other children.”

Sober as a college student? Why Gen Z shrugs at alcohol.

In a cultural shift, younger Americans no longer view alcohol as a status symbol of adulthood. Many are drinking less, or not at all.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Members of Generation Z are showing less interest in alcohol as a marker of adulthood than previous generations. It’s too soon to say whether this will mark a long-term shift akin to the decline in smoking cigarettes. But more 20-somethings are choosing to drink less frequently or abstain altogether. And millennials, now in their 30 and early 40s, are also dialing back alcohol consumption or nixing it entirely.

“It’s starting to become mainstream,” says John Wiseman, who founded a nonalcoholic beverage brand in 2015. “It’s right on the cusp, just the way that veganism and vegetarianism was like 10 years ago.”

This is not to say that Gen Z considers itself more ascetic than previous generations. The decline in drinking over the past decade has come as many states have legalized marijuana. And the biggest growth appears to be in young people who are drinking less, rather than totally abstaining.

Sipping on a glass of nonalcoholic pinot noir, Chasity Townsend says she first became sober to show solidarity with a cousin who was quitting drinking. It was hard at first, she says, but “I’ve never felt this healthy before.”

Sober as a college student? Why Gen Z shrugs at alcohol.

The menu at Binge Bar in Washington lists drinks like a Timeless Old Fashioned, Soul Spiced Apple Cider Mimosa, and Green Apple Mule. But there’s a twist: Everything is zero proof. It’s the area’s first (and only) alcohol-free bar, joining cities like Austin, Salt Lake City, San Francisco, and Omaha, Nebraska.

The average number of drinks consumed by Americans has been declining for more than a decade from 4.8 drinks per week in 2009 to 3.6 in 2021. The trend is being driven by younger adults, with the number of Gen Z and millennials who reported drinking less – or not at all – increasing over the past several years.

Members of Gen Z are showing less interest in alcohol as a symbolic marker of adulthood than previous generations. It’s too soon to say whether this will mark a long-term shift akin to the decline in smoking cigarettes, with only 5% of young adults now lighting up. But more 20-somethings are choosing to drink less frequently or abstain altogether. And millennials, now in their 30 and early 40s, are also dialing back alcohol consumption or nixing it entirely.

“It’s starting to become mainstream,” says John Wiseman, who founded a nonalcoholic beverage brand in 2015. “It’s right on the cusp, just the way that veganism and vegetarianism was like 10 years ago. That’s where sober curiosity is now.”

This is not to say that Gen Z considers itself more ascetic than previous generations. The decline in drinking over the past decade has come as many states have legalized marijuana. And the biggest growth appears to be in young people who are drinking less, rather than totally abstaining. But colleges are reporting growing interest in substance-free housing. And the trend appears to have begun prepandemic, with 28% of college students in 2018 saying they eschewed alcohol entirely, up from 20% in 2002, according to a 2020 study by the University of Michigan.

“It’s been in the zeitgeist for a few years now. And people are realizing that it’s just as cool to choose whatever you want to do with your body when it comes to your diet and your health,” Mr. Wiseman says. More people are cutting back “now that the stigma around not drinking is not exclusively around sobriety, but more just out of sober curiosity.”

A higher number of Americans than ever now say that consuming one to two drinks a day is unhealthy, up 11% from 2018. That increase is highest among adults 18-34, 18% more of whom now say alcohol consumption is detrimental than in 2018. Among Americans aged 35-54 there’s a 13% increase. Among those 55 and older, there’s virtually no change.

Mentions of nonalcoholic beverages on social media, including recipes, were up by over 10% from 2020 to 2021.

Current guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends no more than two drinks a day for men and one for women, and the World Health Organization maintains that no level of alcohol consumption is healthy. The Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction also released guidance stating that no level of alcohol consumption is safe and recommended a maximum of two drinks per week.

Having mocktails on a menu is a good selling point to customers, whether they’ve been sober for one day or for years, says William Jovel, the head bartender at Residents Cafe & Bar in Washington. “We approach all our drinks with the same mentality,” says Mr. Jovel, in terms of sophistication – which is why people are willing to pay the same for a mocktail that they would for a cocktail.

Mr. Jovel has been sober for six years, during which time he’s seen a definite expansion of nonalcoholic spirit brands like Seedlip and Lyre, along with more options for nonalcoholic wines and beers.

There’s been “an uptick in nonalcoholic spirits,” especially post-pandemic, says Krystle Hewitt, food and beverage director at The Pembroke at The Dupont Circle hotel in Washington. “There’s a trend of people trying to be more cautious about what they’re intaking,” she says.

Some people came out of the pandemic feeling that they drank too much, says Ms. Hewitt. “People connect socializing with drinking, and because alcohol and socializing kind of go hand-in-hand, people who were choosing to live soberly for a very long time were ostracized for not drinking.”

The increase in nonalcoholic offerings “is allowing [sober] people to have all of the same things that drinkers have,” she says. “It’s nice to be able to offer maybe someone that’s Muslim or from another religion that can’t have alcohol a nonalcoholic option, so that culturally they don’t feel secluded based off of their religion.”

It’s the norm now for bars or restaurants to have two to three mocktails on their menu, says Ms. Hewitt. The popularity arc is similar to that of vegan food, she adds. “Ten years ago, no one thought about nonalcoholic beverages.”

A growing number of sober or “sober curious” celebrities are launching their own nonalcoholic beverage brands – from actor Danny Trejo and his nonalcoholic tequila, to singer Katy Perry’s nonalcoholic sparkling aperitifs, to football player J.J. Watt’s nonalcoholic beer.

While the culture is growing, it still isn’t the norm everywhere. Chasity Townsend, who moved to Washington from Arizona a few months ago, says it was tricky to find nonalcoholic options. And if a bar or restaurant did carry something, it was usually the same nonalcoholic beer every time. In D.C., most places offer options.

Sipping on a glass of nonalcoholic pinot noir at Binge Bar, Ms. Townsend says she first became sober to show solidarity with her cousin who was quitting drinking. It was hard at first, but she says, “I’ve never felt this healthy before and this in tune with my body.”

She remains sober mainly for her health. “It’s just something I wanted to do for myself,” she says.

“Honestly, beginning was really, really difficult because a lot of events and gatherings are so solely focused around alcohol. It’s really, really hard not to drink,” says Ms. Townsend. “Ultimately, it was a mental thing. It got easier.”

Gigi Arandid, the owner of Binge Bar, opened it in February to fill what she saw as a void for people battling addiction. “I wanted to open a space for people who wanted a safe space to manage their recovery,” she says.

Coming out of the pandemic “catapulted the industry forward,” she says.

Mr. Wiseman of Curious Elixirs saw the same effect. “Our growth started skyrocketing. I think a lot of people were drinking more. But then there were also a lot of people who were looking to make a change.”

The market isn’t just tens of thousands of people anymore, he says. Now it’s millions.

“The main group that has exploded in 2023, it’s the people who are just looking to drink less. It’s not the complete teetotalers,” he says. “That number is growing too, but the number that’s growing faster is the people who are cutting back.”

Curious Elixirs saw a surge in sales in 2021, followed by another in 2022. Mr. Wiseman calls 2023, “the inflection point, where instead of growing 30% to 50% ... [in] September, for example, we had 125% growth.”

Interest in nonalcoholic options “is cross-cultural,” Ms. Arandid says. Binge Bar has hosted events for a polyamory group, a solar company, and a Christian music group, in addition to pop up events with local retailers.

It also appeals to people who still drink alcohol occasionally – like one of Binge Bar’s bartenders. That’s why Ms. Arandid chose “venu ut es” as the bar’s tagline: It translates to “come as you are.”

A poem keeps them goin’ in the US Navy

Poetry aboard U.S. aircraft carriers has been derided as evidence of a “too woke” Navy. Sailors disagree and keep up a New Year’s Day tradition by writing logbook entries in verse.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

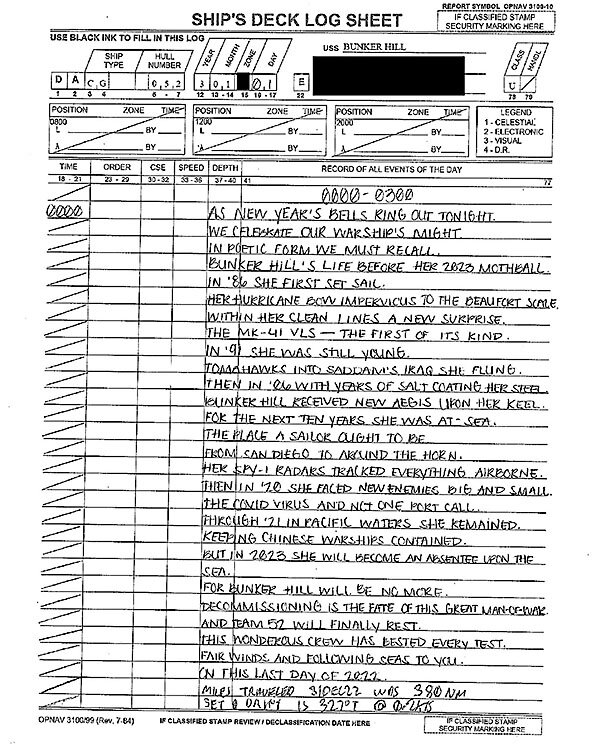

It’s U.S. Navy tradition that the first entry of the new year in ship logbooks be written in verse.

Some sailors angle for the job as a chance to inject a bit of personality – even poetic depth – into a format that discourages it; others try to avoid such a mission.

To delight readers in rhyme is no easy task – particularly given that deck logs are also legal documents that must convey essential information. When a Navy ship hosted a spoken-word event last year, a few U.S. lawmakers decried the practice as too “woke.”

“We’ve got people doing poems on aircraft carriers over the loudspeaker,” Republican Sen. Tommy Tuberville of Alabama said. “It is absolutely insane the direction we’re headed in our military.”

But poetry has a storied history in the armed forces. Military poems can be “incredibly moving and speak, in many cases, to the cost and sacrifice of war,” says Samuel Cox, director of the Naval History and Heritage Command, which hosts an annual competition for the best New Year’s deck log poem.

Service members voluntarily endure “considerable sacrifice in time away from home,” Mr. Cox says. Poetry is one way “to try and relieve the sadness, if you will, of separation.”

A poem keeps them goin’ in the US Navy

It’s U.S. Navy tradition that the first entry of the new year in ship logbooks be written in verse.

Some sailors angle for the job as a chance to inject a bit of personality – even poetic depth – into a format that otherwise discourages it; others try to avoid such a mission.

To delight readers in rhyme is no easy task – particularly given that deck logs are also legal documents. By Defense Department mandate, they must convey less-than-lyrical details about things like commanders on duty and the status of ship systems.

An additional hurdle: Warrior-produced poetry has recently acquired a few powerful detractors. When a Navy ship hosted a spoken-word event last year, some U.S. lawmakers decried the practice as too “woke.”

“We’ve got people doing poems on aircraft carriers over the loudspeaker,” Republican Sen. Tommy Tuberville of Alabama said on Fox News in September. “It is absolutely insane the direction we’re headed in our military.”

Yet poetry has a storied history in the armed forces, military leaders are quick to point out. Lawmakers worrying about poetry detracting from battle skills are perhaps “just ill-informed,” says Samuel Cox, director of the Naval History and Heritage Command, which hosts an annual competition for the best New Year’s deck log poem.

U.S. forces remain “ready to go to war if they have to. But the objective is to deter it.” In the course of doing this, service members voluntarily endure “considerable sacrifice in time away from home,” Mr. Cox says. Poetry is one way “to try and relieve the sadness, if you will, of separation.”

It’s also a potential morale-builder, he adds. “The more good people you retain because they like being on ships – they like being at sea despite the hardships – that’s what our nation needs.”

And sometimes poetry has been a way to process tragic losses. “In Flanders Fields” was written by a soldier to commemorate a battleground where a million comrades in arms were wounded and killed. Another World War I poet, Lt. Wilfred Owen, produced powerful verse while fighting on the front lines. Before he died in battle he considered:

The pity of war, the pity war distilled.

Now men will go content with what we spoiled.

“They are incredibly moving and speak, in many cases, to the cost and sacrifice of war,” says Mr. Cox, a retired rear admiral.

From mischievous to Odysseus

The winners of the Navy’s New Year’s deck log competition tend to summarize events of the year with a soupçon of levity.

Alexis Van Pool, the history and heritage command’s deck log program coordinator, recalls a funny favorite from a 2021 submission: “They thought 2019 had been a crazy year, but 2020 said ‘Hold my beer.’”

Ms. Van Pool’s grandfathers both served as sailors in the Pacific during World War II, and reading their ships’ old deck logs gives her an “enormous” feeling of connection to them, she says.

Such a sense of heritage is what Lt. Artem Sherbinin drew upon when he composed his New Year’s Day deck log for the U.S.S. Bunker Hill, the winner of last year’s contest.

There were no takers until Lieutenant Sherbinin, the ship’s navigator, jumped in. He aimed high. “The story of Odysseus is one giant log of a long journey, you could argue,” he says.

As he dug in, Lieutenant Sherbinin perused a bunch of old deck logs, including from ships in the Gulf of Tonkin during the Vietnam War. “They talk about the surreal feeling of being in and around Vietnam while watching the great political turmoil of 1968 and domestic unrest” unfold in America.

Lieutenant Sherbinin could identify with this, he says, having been at sea during the COVID-19 lockdowns of 2020, when George Floyd was killed and protesters took to the streets.

As he dug into his own deck log poem, the “massive changes” then taking place in America were “sort of top of the mind.”

Lieutenant Sherbinin also drew on the legacy of his ship, which was soon to be decommissioned, to share it, he imagined, with future sailors:

In ’91 she was still young

Tomahawks into Saddam’s Iraq she flung.

Then in ’06 with years of salt coating her steel

Bunker Hill received new aegis upon her keel.

For the next ten years she was at sea.

The place a sailor ought to be

From San Diego to around the Horn

Her spy-1 radars tracked everything airborne.

Then in ’20 she faced new enemies big and small

The Covid virus and not one port call.

Through ’21 in Pacific water she remained

Keeping Chinese warships contained.

The history and heritage command particularly liked this poem “because we got to know not just the voice of the sailor, but the whole history of the ship,” Ms. Van Pool says.

After Lieutenant Sherbinin’s victory came notes of congratulation, including from navigators on the U.S.S. Bunker Hill in the 1980s as well as from Navy sailors from other ships back to the 1950s.

They bonded over shared experience. “I could tell them, ‘Yeah, I’d just gotten off watch and had to sit at my desk for three hours instead of catching those hours of sleep.’ And they can relate.”

Navy tradition, he adds, “builds that connection across generations of mariners.”

Navigating a new year, calendar in hand

In an increasingly digital age, nostalgic throwbacks – like paper calendars – offer a grounding source of comfort and purpose.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Danny Heitman Contributor

To prepare for the new year, I recently trekked to the local stationery shop for a paper calendar, still drawn to the pleasures of this decidedly retro commodity. I love an old-fashioned calendar’s sense of time as a story, the coming 12 months arranged as neatly as books on a shelf.

My paper calendar makes the days seem real. Time, already a mystery, can feel even more abstract when doled out by the teaspoon on a smartphone. But when I open my traditional calendar, time becomes tangible, a visual map of my life.

I also enjoy the sheer blankness of each unblemished page, January as open and white as a winter landscape. Soon enough, the squares will cloud as I scribble in deadlines and dental appointments, business meetings and oil changes.

In the tug and pull of a closely scheduled life, I’m heartened by the vacant spaces of a calendar, like a string of August dates, empty as a castaway beach, their blocks marked by a single word: “Vacation.”

Each new paper calendar brings a chance to start over. I open to January, pen in hand, and begin to write the next chapter of my life.

Navigating a new year, calendar in hand

When my co-workers switched to digital calendars a few years ago, I went along, too. You can’t beat the efficiency of software that logs each appointment and sends little pop-up reminders of when and where you’re supposed to be, a not-so-gentle tug on the sleeve that I’ve come to rely upon.

Even so, to prepare for the new year, I recently trekked to the local stationery shop for a paper calendar for 2024, still drawn to the pleasures of this decidedly retro commodity. I love an old-fashioned calendar’s sense of time as a story, the coming 12 months arranged as neatly as books on a shelf. I flip through the pages of each new calendar in a quick check of their chronology, pleasantly assured that July is once again slated to follow June.

I also enjoy the sheer blankness of each unblemished page, January as open and white as a winter landscape. Soon enough, the squares will cloud as I scribble in deadlines and dental appointments, business meetings and oil changes, social functions and family gatherings. It’s odd how quickly a year begins to hum, the calendar’s grids darkening, like a hive of bees, with the urgency of things to do.

In the tug and pull of a closely scheduled life, the remaining vacant spaces of a calendar begin to stand out even more. I exhale a bit each time I see Sunday on my paper calendar, its little block as hollow as a glass jar, just waiting to be filled with whatever I please. I’m also heartened each summer by a string of August dates, empty as a castaway beach, their blocks marked by a single word: “Vacation.”

Beyond those respites, as I burrow through the obligations that fill a year, my paper calendar makes the days seem real. Time, already a mystery, can feel even more abstract when doled out by the teaspoon on a smartphone app. But when I open my traditional calendar and lay it flat on my desk, time becomes tangible. What I’m seeing, in the march of months stretching toward the future, is a map of my life.

Opinions vary on the best paper calendar to get. Some folks like the novelty kind, with each month devoted to a colorful cat, a tropical bird, a shaggy dog, a majestic nature scene, or a vintage cartoon. These sorts of calendars were a forerunner, I suppose, of the screensavers on computers – a way to give ordinary days a sense of occasion. Those themed calendars can be a lot of fun, although maybe, like online life, they can try a bit too hard to curate each moment as a spectacle or a punchline.

I prefer plain calendars, in which the months themselves are the stars. The months we use to keep time should be arresting enough, growing as they do from classic mythology. Here’s to January, named after Janus, the Roman god of beginnings and endings, and February, a nod to februum, with its ancient rites of purification. Breeze through the other months, whether May with its distant festivals of fertility or July and its homage to Julius Caesar, and even a basic calendar can frame time as a cosmic pageant, one that doesn’t need a canned photo of a folded sunset to gild its significance.

The calendar I prefer is styled like a decent spiral notebook, with a simple black cover as plain as a Pilgrim’s shoe. Pocket-size calendars strike me as too small, compressing the year into a hard lump of coal. Those huge desk calendars that sprawl across like bathmats are, on the other hand, somewhat too massive for me. I don’t want a tableau as big as a board game to navigate a week.

Looking at life in the rearview mirror of a depleted calendar can be wistful. I see parties attended, christenings celebrated, birthdays marked, and projects either satisfyingly completed or regretfully abandoned. I sometimes notice canceled lunch dates with good friends that were never rescheduled, which makes me resolve to embrace and prioritize meaningful connections.

Fortunately, each new paper calendar brings a chance to start over. I open to January, pen in hand, and begin to write the next chapter of my life.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Classroom lessons in discerning truth

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The problem of digital disinformation has set governments scrambling to protect two tenets of democracy that seem increasingly at odds with each other: fair elections and freedom of speech. Yet behind the debates over how or whether to regulate the modern public square, a simpler solution has quietly advanced.

This week California becomes the fourth U.S. state to require its public schools to teach digital literacy from kindergarten through high school. It follows New Jersey, Delaware, and Texas, which have all taken similar steps. The purpose of these measures, as the California law states, is to build “critical thinking” and “strengthen digital citizenship.”

That offers a cue at a time of heightened concern for the integrity of upcoming elections, from Taiwan to the United States. The laws are an acknowledgment that the solution to digital dishonesty ultimately resides in individual reason and self-government – qualities that are inherent in everyone.

Good digital citizenship, says Alice Huguet, an education researcher at the Rand Corp., means “engaging in civil dialogue.” It includes sharing information responsibly, she recently told The Guardian. The education reforms in California and other states may end up showing that when people are able to discern digital dishonesty, they may also be less likely to distribute it.

Classroom lessons in discerning truth

The ever-more sophisticated forms of digital disinformation have set governments scrambling to protect two tenets of democracy that seem increasingly at odds with each other: fair elections and freedom of speech. Yet behind the debates over how or whether to regulate the modern public square, a simpler solution has quietly advanced.

This week California becomes the fourth U.S. state to require its public schools to teach digital literacy from kindergarten through high school. It follows New Jersey, Delaware, and Texas, which have all taken similar steps. More than a dozen other states are moving in the same direction.

The purpose of these measures, as the California law states, is to build “critical thinking” and “strengthen digital citizenship.” That offers a cue at a time of heightened concern for the integrity of upcoming elections, from Taiwan to the United States. The laws are an acknowledgment that the solution to digital dishonesty ultimately resides in individual reason and self-government – qualities that are inherent in everyone.

Digital literacy “refers to the knowledge, skills and attitudes that allow children to be both safe and empowered in an increasingly digital world,” according to UNICEF. Rather than treating it as a unique subject, the California law requires educators to fold it into everything they teach, from math to literature.

That approach draws on experience in more than 50 countries as diverse as Finland and Uganda. It taps the distinct ways that different disciplines teach students how to gather and analyze information. In the U.S., the movement toward digital literacy in education is one of the few policy fields that garner broad consensus across red and blue states.

One reason is the emphasis on safety. Digital literacy teaches children from an early age to start recognizing potentially harmful information and question the veracity of sources. A Stanford study this past year found that after just six 50-minute lessons, high school students were twice as likely to spot suspicious websites.

“This law isn’t about teaching kids that any specific idea is true or false, rather it’s about helping them learn how to research, evaluate, and understand the information” they encounter online, said New Jersey state Sen. Michael Testa about the law his state adopted last year.

What’s good for the health and safety of individuals, however, has a civic equivalent. Good digital citizenship, says Alice Huguet, an education researcher at the Rand Corp., means “engaging in civil dialogue.” It includes respecting digital privacy and sharing information responsibly, she recently told The Guardian. The education reforms in California and other states may end up showing that when people are able to discern digital dishonesty, they may also be less likely to distribute it.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘Behold, I make all things new’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Karen Neff

As we head into a new year, we can let God’s promise of newness inspire progress and healing – and continue this all year.

‘Behold, I make all things new’

Ringing in a new year affords an opportunity to reflect on the past year while we ponder what steps we wish to take in the new. Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, wrote, “A new year is a nursling, a babe of time, a prophecy and promise clad in white raiment...” (“Pulpit and Press,” p. 1). Reflection can be truly inspiring as we turn to God for enlightenment.

One year, as I considered the potential the new year held, this line from the Bible came to thought: “Behold, I make all things new” (Revelation 21:5).

This is not only a present promise but also an eternal law of God, Spirit, that applies to all of us. God’s creation of man – each of us as His spiritual image – is fully made, eternally. Yet God’s loving and conscious knowing of each of us wasn’t a one-time event. It is an ongoing consciousness of all His spiritual offspring as perpetually vibrant and free.

A growing understanding of this helps deliver us from thoughts that aren’t from God and thus aren’t truly part of us – such as limiting thoughts relating to aging, accident, lack, or disease. This cleansing takes place through Christ – the active, healing message of God’s power and goodness – and unfolds greater health, progress, and opportunity.

I also like to think of “I make all things new” as “I make all things now!” All of God’s spiritual gifts are bestowed moment by moment, uplifting us in fresh, enlivening, strengthening ways that bless.

One time as a new year approached, I prayed for God to reveal to me what I needed in the coming year. Almost immediately came the thought, “I want to live a spiritually inspired life!”

This was a revelation to me, but I realized it truly was my heart’s desire. From that point on I prayed each day to open myself up to the inspiration God is always pouring forth. And it came! I awoke to unique, dawn-fresh, divine Soul-inspired, healing thoughts every day, and this has continued as I’ve prayed to remain humbly receptive. And such inspiration isn’t available only to certain people. It’s here for everyone.

Christ Jesus was the epitome of one who lived an inspired life that was perpetually fresh and new. “He was inspired by God, by Truth and Love, in all that he said and did,” Mrs. Eddy wrote (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 51). The influx of ideas that came to him from God, revealing man’s true nature as God’s whole and pure likeness, empowered him to heal countless people. And those healing ideas are here for us, too.

There is no limit to the blessings we can experience as enlivening spiritual inspiration pours in. In my case, a greater consciousness of our eternal, spiritual nature brought a vigor, energy, and freshness that I hadn’t experienced previously. It’s not just that I felt years younger; I felt ageless – as we all truly are.

We can quietly and meekly turn to God for a vitalizing sense of newness, right now. Then we find we are not only blessed but also a blessing to others in new ways, as we witness the ongoing fulfillment of our Father’s promise, “Behold, I make all things new.”

Viewfinder

Honoring past warriors

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Tomorrow we’ll look at legal attempts to keep Donald Trump off the 2024 presidential ballot in several states, with Maine now following Colorado. What originally looked like a long shot has picked up momentum, but will the result be any different?

And please send us any feedback you have about our new news briefs. You can email me at editor@csmonitor.com.