- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Russia, NATO: How GOP shifted from Reagan’s confident view

- Today’s news briefs

- Beyond Santos: A special election with import for the future

- Fine print justice: How Daryl Atkinson is battling bureaucracy

- A small town, public art, and the First Amendment

- Father and son cooking duo stirs up Chinese cuisine

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

When individuals take action

They’re called “wealth stripping” policies – government and private fees that hit struggling families hard. Some are relatively small, such as a citation for an expired license plate. Others, like fees that follow people out of prison, are not. Their impact can snowball because of inability to pay.

Our cover story today dives deep into an issue that often hides in plain sight. You’ll learn about troubling practices. You’ll also see what can happen when individuals decide to take action. The people in our story aren’t all famous or powerful. But they’ve seen opportunities for progress and reform – and cities and states are responding.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Russia, NATO: How GOP shifted from Reagan’s confident view

Ukraine and Europe have been closely monitoring the internal Republican debate over funding for Ukraine’s war effort, long before former President Donald Trump’s weekend remarks on Russia and the NATO alliance. Is GOP isolationism here to stay?

President Ronald Reagan embodied the confident and cheerful America that would defeat the Soviet Union and welcome Eastern European countries into the family of democracies. He was the last president to succeed at immigration reform.

Today, Republicans in Congress hold up military assistance for a besieged Ukraine, and former President Donald Trump boasts at a weekend campaign rally that he would “encourage” Russia to attack any NATO allies that aren’t meeting the alliance’s financial targets.

What happened? Foreign policy analysts point to a shift in the Republican base from the business class to working class, as well as a sense that has grown for years that the United States was trying to do too much while ignoring problems at home.

Yet some say the right leader with a compelling vision could shift the party back to something closer to Mr. Reagan’s optimism.

America’s foreign policy establishment “had these grand visions of remaking other societies, but they were too ambitious,” says Paul Saunders, who served under President George W. Bush. “Trump was very effective at capitalizing on the public rejection of that leadership approach, but he didn’t really define a vision,” he adds. “The Republicans are left with all of these different influences and concerns that give us this swirling mix we have right now.”

Russia, NATO: How GOP shifted from Reagan’s confident view

Republicans in Congress hold up military assistance for a besieged Ukraine, while expressing admiration for the strongman leadership style of Vladimir Putin.

Former President Donald Trump, the Republican standard-bearer and the party’s increasingly likely presidential nominee, boasts at a weekend campaign rally that he would “encourage” Russia to attack any NATO allies that aren’t meeting the alliance’s financial targets.

And a growing number of Republican officials employ Mr. Trump’s isolationist and xenophobic rhetoric in the ongoing immigration debate.

With the party’s traditional internationalist outlook nowhere in sight, one has to wonder: What happened to the foreign policy of Ronald Reagan’s Republican Party?

President Reagan embodied the confident and cheerful America that would defeat the Soviet Union and welcome Eastern European countries into the family of democracies. He was the last president to succeed at immigration reform, with legislation that legalized nearly 3 million unauthorized immigrants.

When he left office in 1989, Mr. Reagan signed off with his vision of America as the “shining city upon a hill” that would have no walls, only doors for admitting those seeking freedom and prosperity. By contrast, today’s Republicans are more likely to say they prefer walls, view migrants as a threat – and dismiss Ukraine’s freedom and security as having little relevance for America.

Foreign policy ebb and flow

What happened?

A shift in the Republican Party’s base – from the business and chamber-of-commerce set that benefited from international engagement, to a more rural and working-class demographic more skeptical about the world and America’s leadership role in it – is one factor, foreign policy analysts say.

But some experts who have worked in Republican administrations as far back as President Reagan’s say that since President George W. Bush’s administration, there has been a growing sense that the United States was trying to do too much while ignoring problems at home. And that sense found its embodiment in Mr. Trump’s aggrieved populism.

Moreover, these experts say, the Republican Party has long been subject to an ebb and flow of the key strains of foreign policy approach marking American history. These range from a Wilsonian international idealism to a Jacksonian populist and isolationist vision of American global engagement.

And while Mr. Trump’s inward-oriented populism may be ascendant right now, some say the right leader with a compelling vision of global engagement could shift the party back to something closer to Mr. Reagan’s optimistic sense of America’s role in the world.

“The American foreign policy establishment broadly had these grand visions of remaking other societies, but they were too ambitious, they didn’t work, they took too long, and the American people got very frustrated with it,” says Paul Saunders, who served in the State Department under George W. Bush.

“Trump was very effective at capitalizing on the public rejection of that leadership approach, but he didn’t really define a vision for American foreign and security policy,” adds Mr. Saunders, now president of the Center for the National Interest, a Washington foreign and security policy think tank. Instead, he says, “the Republicans are left with all of these different influences and concerns that give us this swirling mix we have right now.”

Mr. Saunders notes, for example, that there is a not-insignificant libertarian streak in the party that views an active U.S. role in the world, based on a big military and an extensive “security state”, as “ultimately making us less free here at home.”

Ukraine aid package

The Republican isolationist turn in foreign policy is on particularly stark display in the debate over additional military assistance for Ukraine. Despite increasingly dire reports of Ukraine’s depleted munitions stocks and faltering ability to repel Russian ground assaults and drone attacks, congressional Republicans prefer to highlight an assault they say is going unanswered on the U.S. southern border.

Why help Ukraine secure its borders, many say, if we can’t first secure our own borders?

A Ukraine package could finally pass in the Senate this week, but prospects are much dimmer in the Republican-controlled House.

“Once they had a Reagan who cared very much about the freedom of the Eastern European countries shackled by Soviet rule, but now you hear Republicans saying, ‘Putin wants to take Ukraine? Who cares, we have our own problems,’” says Lawrence Korb, a former assistant secretary of defense during the Reagan administration.

The Republican Party’s isolationist strain was resurgent in the 1996 presidential bid of Pat Buchanan, but it gained momentum in reaction to Mr. Bush’s ambitious and idealistic foreign policy vision, some say.

“The sense of overreach really set in with the second President Bush, who overextended himself in Iraq and Afghanistan and who had this vision of using 9/11 to reform the Middle East,” says Mr. Korb, now a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress in Washington. “That’s when many in the American public started feeling like things were going too far at America’s expense.”

Just how far the Republican Party and indeed the U.S. will swing in the isolationist direction will be determined to some extent by elections in November – and not just in the likely clash between the internationalist, America-as-global-democracy-champion vision of President Joe Biden and the “America First” stance of former President Trump.

The extent of the swing will also depend on what Congress emerges from the November voting.

“It’s the Democrats and Biden who are more worried about the world now and America’s role in it,” says Mr. Korb, “but we’ll see [in the elections] where the American people are on these questions.”

Looking at the Republican trajectory from Mr. Reagan to Mr. Trump, Mr. Saunders says he believes the party will at some point return to a robust internationalist foreign policy – but that it will take a leader who can articulate a compelling vision of America in the world.

“It’s a mistake to hope we can return to some previous consensus or a particular leadership that responded to an earlier era. The past is the past and we’ve moved beyond that,” he says.

Yet he adds, “The internationalist wing of the party may be in the minority right now, but I don’t think it’s impossible at all to imagine someone with real leadership skills defining a new internationalist American role that could appeal even to the decidedly less internationalist wing of the party.”

Today’s news briefs

Trump appeals to Supreme Court: Former President Donald Trump asked the U.S. Supreme Court for an emergency stay in the Jan. 6 election interference trial after his appeals court loss. His lawyers maintain he has near absolute immunity for actions taken while president.

Pakistan protests: Supporters of imprisoned former Prime Minister Imran Khan blocked highways and started a daylong strike to protest alleged vote-rigging in Feb. 8 elections. Allies of Mr. Khan won more seats than the political parties that ousted him nearly two years ago.

Finland’s election runoff: After a narrow win, former Prime Minister Alexander Stubb will take up the powerful post of president in March. Mr. Stubb’s responsibilities will include integrating the NATO newcomer into the military alliance.

Migratory animals struggling: Nearly half of the world’s migratory species are in decline, according to a United Nations report. They are imperiled by habitat loss, illegal hunting and fishing, pollution, and climate change.

Beyond Santos: A special election with import for the future

Experts caution against reading too much into special elections. But both parties will be watching the vote in former Rep. George Santos’ district for what it signals about campaign messaging and voter engagement.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Tuesday’s special election in New York’s 3rd Congressional District matters to both parties for reasons that have nothing to do with George Santos.

For one thing, whoever wins the seat previously held by the expelled GOP congressman may become a decisive vote in the narrowly divided House of Representatives. And with just nine months to go before November, the race offers an early test of campaign messaging in a swingy suburban district.

At the same time, strategists will be looking to see if Tuesday’s results confirm a pattern that has been emerging in recent special elections – and that could herald a major rethink in how both parties approach everything from the rules around voting to the types of campaigns they run.

Do Democrats now have a leg up in low-turnout elections?

For years, Republicans tended to have an edge in lower-participation contests – off-year and special elections, and other nonpresidential votes – while Democrats did better in high-turnout environments. But recently, that dynamic seems to have flipped.

It’s the effect of a larger partisan realignment, as Democrats have been winning over more college-educated voters, who tend to be highly engaged, while Republicans have gained ground among nonwhite voters and those without a college degree, who often only turn out in presidential years.

Beyond Santos: A special election with import for the future

Tuesday’s special election in New York’s 3rd Congressional District matters to both parties for reasons that have nothing to do with George Santos.

For one thing, whoever wins the seat previously held by the infamous ex-congressman will become a potentially decisive vote in the narrowly divided House of Representatives.

And with just nine months to go before November, the race offers an early test of campaign messaging in a swingy suburban district. President Joe Biden won by 8 points here in 2020, before Mr. Santos – the recently expelled Republican who misused campaign funds and lied about almost every aspect of his résumé – won by an almost equal margin in 2022. The Long Island district is rated by the Cook Political Report as a “toss-up,” with former Democratic Rep. Tom Suozzi holding a narrow lead in recent polls over Republican Nassau County Legislator Mazi Pilip.

At the same time, strategists will be looking to see if Tuesday’s results confirm a pattern that has been emerging in recent special elections – and that could herald a major rethink in how both parties approach everything from the rules and restrictions around voting to the types of campaigns they run.

Do Democrats now have a leg up in low-turnout elections?

Typically, non-presidential elections draw fewer voters to the polls than contests with presidential candidates on the ballot. And special elections, like the one being held Tuesday in NY-03, tend to feature very low participation, since they occur on randomly determined days (when voters aren’t used to voting) and only feature one race.

For years, Republicans tended to have an edge in those types of circumstances, while Democrats did better in high-turnout votes. But recently, that dynamic seems to have flipped.

In the 2022 midterms, Democrats held off a predicted “red wave” in the polls, instead growing their edge in the Senate and keeping House losses to the single digits. Then, in 2023’s off-year elections, a Democratic governor won reelection in Kentucky and Democrats retook Virginia’s lower chamber while retaining a majority in the state Senate. Over the past two years, abortion and marijuana referendums have prevailed in states like Kansas and Ohio.

“If there is one data-geek debate of 2024, it’s the hypothesis that partisan engagement has reversed,” says David Wasserman, senior elections analyst at the Cook Political Report.

If so, it’s likely a downstream effect of a larger realignment that’s been happening between the two parties, as Democrats have been winning over more college-educated voters, who tend to be highly engaged, while Republicans have gained ground among nonwhite voters and those without a college degree, who often only turn out in presidential years.

Highly engaged voters, many of whom are particularly passionate about a single issue, such as abortion, “can exert disproportionate influence” in elections with lower participation, says Patrick Ruffini, a Republican pollster. That’s less true in a presidential year, when a larger pool of voters becomes energized and mobilized.

As such, a Democratic win on Tuesday – particularly a narrow one – won’t necessarily portend good news for the party in November.

“Democrats are in better shape [on Tuesday] because it is a special election than they would be if it was a regular election,” says Mr. Wasserman. “But the fact that Democrats did well in 2023 and special elections doesn’t change my thinking about the fall and how challenging it will be for Democrats. ... Biden and Democrats might hope for lower turnout rather than higher.”

Another special election in New York – held in August of 2022, after Democratic Rep. Antonio Delgado resigned to become lieutenant governor – signaled these new turnout dynamics. Democrat Pat Ryan defeated Republican Marc Molinaro in the NY-19 District by fewer than 3,000 votes, despite polling that had consistently shown Mr. Molinaro ahead. Just three months later, when voters in the Catskills district returned to the polls to cast ballots in the bigger midterm elections, turnout more than doubled from August. Mr. Ryan, running in a more Democratic-friendly district due to redistricting, eked out a win by an even slimmer margin.

One factor that has long favored Republicans in low-turnout contests is strong support from older people, who are among the most committed voters. That’s still an advantage, say GOP strategists. But the shift of highly educated voters, including educated senior citizens, to Democrats is a strong counterweight.

“Turnout is a function of age, but also education. You’ve had education be a big demographic driver for Democrats in the Trump era and counter a Republican advantage among older voters,” says Mr. Ruffini.

Despite having a greater share of highly educated voters than the national and state averages, some experts say New York’s 3rd District could prove an exception to the recent special-election trend. This area was the inspiration for the famous Ronald Reagan quote, “When a Republican dies and goes to heaven, it looks a lot like Nassau County,” and it has had some success thwarting Democratic suburban gains.

“Between manpower and messaging, the Nassau Republican Party has had an uncanny ability to overcome an electorate that’s changed dramatically in a generation,” says Lawrence Levy, dean of the National Center for Suburban Studies at Hofstra University. “I’ve been polling on politics for 50 years, and this race is as interesting as it gets.”

In recent weeks, much of the campaign has turned on immigration. Ms. Pilip has been hammering on the topic, in an effort to drive more GOP voters to the polls, with GOP-funded TV ads accusing Mr. Suozzi of supporting “sanctuary cities,” and featuring a viral video clip of migrants in New York attacking a police officer.

Mr. Suozzi has tried to blunt these attacks by telling voters that he agrees the border is “chaotic” and Democrats need to do a better job of addressing it. He may have been helped by events in Washington last week, as Republicans in Congress tanked a bipartisan border deal under pressure from former President Donald Trump.

Nationally, immigration has become a top concern among voters, and will likely be a defining issue in this year’s presidential election. As such, experts say other campaigns may look to NY-03 as a test case of campaign messaging.

“The border issue is going to be around the rest of the year, and if Republicans are going to win in a swing district, this is a good chance to prove its potency,” says Jay Townsend, a New York political consultant who advises candidates from both parties. “If Pilip loses, they will have to adjust their playbook, because they have bet the whole kitchen sink on the border issue in this race.”

A deeper look

Fine print justice: How Daryl Atkinson is battling bureaucracy

On paper, court fees and ticket fines help balance local budgets. But a deep dive suggests the harm they cause far outweighs any revenue raised.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 15 Min. )

-

By Courtney E. Martin Special contributor

Attorney Daryl Atkinson won a 2014 White House award and later co-founded the legal reform nonprofit Forward Justice. He also has a criminal record.

In 1996, Mr. Aktinson was convicted of a nonviolent drug offense. He served the four-year mandatory minimum of his 10-year sentence before leaving prison ready to start over. But first he had to figure out how to get to the grocery store without a driver’s license (it had been automatically revoked) and how to pay off the $50,000 in fees and fines that went home with him.

Eventually, he worked out a payment plan, and he and his family persevered – for 24 years. “I was finally free from feeling under the lash of the state,” he says.

The impact of criminal justice fees and traffic violation fines, in particular, is felt across the United States. According to a recent report, 1 in 3 American families are directly impacted by legal fines and fees, and at least 17 million families with children sacrifice on essentials due to court debt.

But a growing movement has been fighting back and winning reforms, including those related to the loss of driving privileges due to unpaid fines and fees. Twenty-four states have enacted significant reform since 2017.

In one instance, Durham County, North Carolina, District Attorney Satana Deberry dismissed 559 fines at once.

“With their debts forgiven,” she said, “these individuals can now get a driver’s license. They can get insurance. They can go to work and to school. They can participate fully in the economic and social vitality of our community.”

Fine print justice: How Daryl Atkinson is battling bureaucracy

Daryl Atkinson has a law degree from the University of St. Thomas School of Law. He received a 2014 Champions of Change Award from the White House and went on to become the inaugural “Second Chance” fellow in Barack Obama’s administration from June 2015 through the end of the administration. And in 2016, he co-founded one of the highest-impact nonprofits doing legal reform in the South: Forward Justice.

He also has a criminal record. In 1996, he was convicted of a nonviolent drug offense and sentenced to 10 years in prison. He served the mandatory minimum of four years and got out ready to start over. But first he had to figure out how to get to the grocery store without a driver’s license (it had been automatically revoked) and how to pay off the $50,000 in fees and fines that went home with him from prison.

Mr. Atkinson remembers one particularly harrowing day. He had been piecing his life back together, making his dream of going to law school a reality, when he got a call from his mother. “Someone came knocking on my door and said they have a warrant for your arrest,” she said, the fear palpable in her voice.

His stomach dropped. When he followed up, he found out that the district attorney’s office had put out the warrant for his failure to pay his criminal justice debt. He worked out a plan with the office – $100 a month while he was still in law school, with more to come once he got his first job – but anytime he fell behind, it would threaten re-incarceration. If he and his wife got a little extra infusion of cash, they put it toward his debt – forgoing a 529 college savings account for their daughter or the other financial things they had so hoped to do to set her up for success. He explains, “All of the bridges towards wealth were stripped away.”

But Mr. Atkinson and his family persevered. It took 24 years to pay off the debt. “I was finally free from feeling under the lash of the state, always called to account around something that I did so long ago, irrespective of what levels of achievement I had attained,” he says. He goes on, “Who is the same as they were two decades ago? When does it ever end? Everyone should be able to relate to that.”

Mr. Atkinson is not alone. Over the past decade, a growing movement in the United States has been fighting back against the fines and fees – largely invisible to the general public – that haunt already economically marginalized people. The most prominent examples are criminal justice fees and traffic violation fines.

Many states, counties, and cities charge people who are incarcerated for phone calls home – a critical connection, proven to reduce recidivism – or for basic toiletries like a toothbrush and toothpaste (marked way up). And those on parole are frequently charged for things like ankle monitor rental. These fees often wind up being paid not by the incarcerated person or parolee but by family members – typically women of color, according to a report by the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights. In 63% of cases, family members were mainly responsible for paying court-related costs connected with convictions. Of those, 83% were women. Many respondents made less than $15,000 annually, while the average debt incurred for court-related fines and fees was $13,607.

Or consider more mundane violations: traffic tickets. Leisa Moseley-Sayles, a Las Vegas City Council campaign manager at the time, was dropping off her two older children at middle school in 2014 when a school police officer pulled her over for not parking close enough to the curb (a common practice during harried school drop-offs, as most parents will attest). When he looked her up in the system, he found a warrant for her arrest due to an unpaid fine related to an expired license plate citation. Even though her younger two children were in the car, the officer said he’d have to take her into the station. “What about my kids?” she asked.

“We’ll take them to Child Haven, a shelter for kids who have been removed from their homes,” he said. “Unless you have a friend you can call.”

Ms. Moseley-Sayles called a girlfriend, who rushed over to grab her children before she was taken away. She was released that afternoon, but the emotional damage to her children had already been done. “We don’t talk enough about the emotional impact of these fines and fees,” Ms. Moseley-Sayles says.

What might seem like a manageable fine to a more economically secure person – let’s say $238 for having a busted headlight in the state of California or $100 for a parking ticket on the streets of Chicago – can have profound repercussions for someone living on the edge.

According to the Fines and Fees Justice Center, 86% of Americans drive to work. If someone has their license suspended because of an unpaid traffic violation, they might lose their ability to get to their job, and eventually lose their job altogether. This can lead not just to economic precarity but also to food insecurity, health complications, and more. In some states, if you owe fines or fees, you can’t vote.

Further, debt-related restrictions on driving privileges force a no-win choice on many people: Stop driving and lose everything, or keep driving and risk more fines, criminal charges, arrest, and jail time. This can make a $100 traffic ticket a slippery slope into justice system involvement. As Lisa Foster, who co-founded the Fines and Fees Justice Center, explains, “For poor families, fines and fees are like flypaper – you get stuck in the system and can’t get out.”

That’s how Ms. Moseley-Sayles felt. Her arrest that day was the result of a $299 citation she had received in 2010. At that time, in a career transition and in the thick of a divorce, she couldn’t afford to pay the initial ticket, nor the payment plan she negotiated. “It’s about an ability to pay, not a willingness to pay,” she says.

The impact of fines and fees is felt all over the nation. According to a recent report by the Wilson Center for Science and Justice at Duke Law and the Fines and Fees Justice Center, 1 in 3 American families are directly impacted by legal fines and fees, and at least 17 million families with children sacrifice on essentials due to court debt.

It’s hard to come by national data for a variety of reasons, but many states have good data. The research shows that in Nevada, where Ms. Moseley-Sayles lives, for example, the most common tickets for which warrants are issued are related to poverty more than to safety: lack of registration, lack of insurance, and equipment violations. It also shows that the poorest communities have the most warrants – by orders of magnitude.

Research also shows that people of color, and Black people in particular, are about 20% more likely than white people to be pulled over. So given that people of color experience poverty at higher rates in the U.S. than white people, those most likely to be ticketed are least likely to be able to pay.

But a growing movement, in part led by those who have been directly impacted, such as Mr. Atkinson and Ms. Moseley-Sayles, is fighting for what might be thought of as “fine print justice” – the repeal of government policies that, sometimes in hidden ways, ask the least financially secure Americans to subsidize government budgets.

First, some history. What was the thinking behind instituting these fines and fees in the first place?

Fines date back to the Middle Ages, when feudal lords would let people pay to get out of their stockades – an alternative to being in custody. Over time, governments realized that there were many offenses that didn’t merit custody. You shouldn’t, for example, go to jail for running a stop sign. So the fine became the alternative punishment. The size of those fines, related to a range of crimes, is a subject of great controversy.

Fees are yet another source of controversy, though they are designed in ways that make scrutiny of them nearly impossible for the average person. Unlike fines, which are supposed to be a form of punishment, fees became a way to raise government revenue. Many pinpoint the beginning of that trend to 1982, when President Ronald Reagan’s administration and Congress decided to abolish a federal agency called the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration overnight. That agency, a vestige of President Lyndon Johnson’s war on crime program, provided as much as $2.7 billion per year to state and local criminal justice systems.

States and counties, floundering to fill the funding gap, started adding fees – sometimes hidden – to all kinds of tickets. By 1984, the federal government created a replacement agency, the Office for Justice Programs, but it took 14 years for the department to get up to the previous level of funding. By then, the fee approach had taken hold across the country.

On top of these dynamics, add President Richard Nixon’s war on drugs, which led to longer sentences and higher fines, and the explosive growth of mass incarceration. Plus, the Great Recession led to austere governments looking to fines and fees to subsidize even the most basic government services. Ms. Foster, of the Fines and Fees Justice Center, explains, “What really happened between 1982 and 2010 is that legislatures started using the justice system as an ATM machine.”

And legislators have largely chosen not to assess whether that ATM is actually working. When Ms. Foster and her colleagues went to all 50 states asking for their data on the fees they impose at the time of conviction, the most straightforward fees to track, only 11 of them could account for what was assessed and collected. Eleven other states could give only partial data because they have municipal courts, which are decentralized and don’t use a shared system for tracking fines, fees, and revenue. New York and Texas, for example, have roughly 1,000 such local courts each. Even so, the Fines and Fees Justice Center team managed to account for $27.6 billion in unpaid fees, but it named the report “Tip of the Iceberg,” as it was clear that this amount was nothing close to the accurate number.

While comprehensive data is scarce, the available data is damning. Using fines and fees to raise government revenue has proved to be profoundly ineffective. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, the counties studied in Texas and New Mexico spend more than 41 cents of every dollar of revenue received from fees and fines for in-court hearings and jail costs to collect that revenue. “That’s 121 times what the Internal Revenue Service spends to collect taxes,” the Brennan Center report notes.

The illogic of these fines and fees was put into stark relief at an unlikely moment: the killing of 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, on Aug. 9, 2014. Many people associate Mr. Brown’s death at the hands of police officer Darren Wilson with the start of mass protests over police violence against Black people, but in the long tail of the unrest, something else significant, albeit quieter, occurred. The Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice released a report that read, in part:

“The department found that Ferguson Municipal Court has a pattern or practice of:

“•Focusing on revenue over public safety, leading to court practices that violate the 14th Amendment’s due process and equal protection requirements.

“•Court practices exacerbating the harm of Ferguson’s unconstitutional police practices and imposing particular hardship upon Ferguson’s most vulnerable residents, especially upon those living in or near poverty. Minor offenses can generate crippling debts, result in jail time because of an inability to pay and result in the loss of a driver’s license, employment, or housing.”

Noting how far beyond Ferguson this issue extends, a follow-on report by several justice agencies was titled “Not Just a Ferguson Problem.” Fines and fees like these are part of a larger category of what academics and advocates call “wealth-stripping” practices – government policies and private sector strategies that extract money from families already struggling financially.

Swarthmore College historian John Caskey’s 1996 book, “Fringe Banking: Check-Cashing Outlets, Pawnshops, and the Poor,” was one of the first to frame wealth stripping, and in the years since there has been ample scholarship on the topic. This way of looking at economic justice asks not simply to raise economically marginalized folks up to the middle class through income- and wealth-building strategies, but also to recognize that current policies keep pulling them back down, no matter how many financial literacy classes or college scholarships exist.

In short, policies that take money away from poor people often prevent them from transcending generational poverty.

Advocate Anne Stuhldreher remembers reading the landmark Department of Justice report about Ferguson and thinking, “I really hope this isn’t happening in California.”

As a grantmaker at The California Endowment, she knew a lot of anti-poverty organizers throughout the state and started asking them about the issue. She remembers a particularly catalytic moment when she was sitting at a big, regional meeting and the director of the East Bay Community Law Center slid a piece of paper across the table to her with a bunch of county names and numbers on it. The list showed the fees that parents were charged when their children got out of juvenile jail. She was shocked: “What? The biggest determinant of how a kid is going to do when they get out of juvenile hall is if they have a relationship with a caring, loving adult. By charging these fees, we’re directly threatening that bond right out of the gate.”

She brought her newly collected data and no small amount of outrage to various government officials in San Francisco. “I kept telling them, this is a lose-lose. You all should start an economic justice agenda,” Ms. Stuhldreher remembers.

José Cisneros, who was San Francisco’s treasurer at the time and, as such, in charge of revenue for the city and county, agreed with her, but on one condition – that she come and run it. That wasn’t Ms. Stuhldreher’s plan, but she couldn’t say no.

And that’s how, in late 2016, San Francisco became the first city in the nation to launch an office called The Financial Justice Project, housed in the Office of the Treasurer & Tax Collector, to assess and reform how fees and fines were impacting low-income people and people of color, in particular. Ms. Stuhldreher recalls that her first goal in her new role was to chase down missing data such as the collection rate on things like probation fees, which turned out to be 9%. And the government was spending a lot of money tracking down that 9%. She started referring to them as “high pain and low gain” fees.

Ms. Stuhldreher explains, “I thought, surely we can hold people accountable without putting them in financial peril. And surely we can balance our budgets without putting it on the backs of the most marginalized people in our city. We had to try.”

The city did more than try. Advocates and officials, together, won huge reforms. San Francisco became a critical testing ground for these insider repeal efforts on a wide range of topics. The city has eliminated administrative fees charged to people exiting jail and the criminal legal system, eliminated overdue library fines and cleared $1.5 million in outstanding debt from these fines, and eliminated San Francisco Public Utilities Commission fees to restore service for people who have had their water shut off – among so much else.

The playbook is basically this: Talk to those most directly impacted by fines and fees, who can pinpoint which ones are giving them the most trouble. Follow the money (namely: What is the collection rate? And what does it cost the government to get that money?). Paint a picture of why fines and fees are a lose-lose so that both government insiders and sympathetic outsiders, like public interest lawyers, community organizers, nonprofit leaders working on immigration or incarceration, etc., understand. Finally, in coalition, push hard for reform. And once you get it at the local level, aim for state reform.

Ms. Stuhldreher began to get inquiries from government advocates around the country who wanted to replicate what she and her team were doing in San Francisco. That’s how the Cities and Counties for Fine and Fee Justice Bootcamp was born (virtually) in May 2020. In sessions run by the national Cities and Counties for Fine and Fee Justice Network, people interested in doing what Ms. Stuhldreher and others have done in their own hometowns, counties, and states can learn best practices and how to avoid common pitfalls. The key questions, for example, to ask about any fine or fee that is ripe for reform are these: Is it effective? Is it fair? Is it equitable? Is it efficient? Is it sustainable?

Many reforms have been seeded through this effort: Dallas and St. Paul, Minnesota, ended debt-based driver’s license suspensions, and Philadelphia passed a budget that ends major commissary markups in prison and provides 165 minutes of free phone-call time weekly for incarcerated people, among much more.

The Fines and Fees Justice Center, for which Ms. Moseley-Sayles is now the Nevada state director, has also had some big wins recently. The organization works on national campaigns as well as state-specific ones in New York, Florida, New Mexico, and Nevada. Nevada issued warrants for both failure to appear (FTA) and failure to pay (FTP) when Ms. Moseley-Sayles got her first ticket; traffic tickets were also considered criminal misdemeanors. Thanks to her work with partners such as a law clinic at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas; the state American Civil Liberties Union affiliate; local immigrants’ rights groups; and the Clark County Black Caucus, they succeeded in decriminalizing traffic violations in Nevada in 2021. The new law went into effect in January 2023. As a result, people given traffic tickets are no longer subject to warrants for their arrest – or to the fees that come with FTA and FTP warrants.

On June 16, 2023, New Mexico officially ended the practice of suspending driver’s licenses for FTA and FTP warrants, a policy change that resulted in hundreds of thousands of New Mexicans regaining the freedom to drive. And in Nevada, a coalition successfully passed significant fine and fee reforms in 2023 with bipartisan support from the Democratic-controlled Legislature and newly elected Republican governor. SB416, which focuses on criminal justice fees, eliminated “room and board” fees – for which 25% of incarcerated people’s already low wages were being garnished to cover those fees. Nevada also outlawed commissary markups, which sometimes amounted to basics like menstrual pads, toothbrushes, and toothpaste costing close to 70% more.

Additionally, in 2019, over 100 organizations – from the Southern Poverty Law Center to JPMorgan Chase – launched Free To Drive: a coalition united by the belief that restrictions on driving privileges should be reserved for dangerous driving, not to coerce debt payment or to punish people who miss a court appearance.

So what’s up next for this growing movement?

Ms. Foster says she is confident that every state will stop suspending driver’s licenses due to debt before long. Twenty-four states have enacted significant reform since 2017, so the movement is well on its way. As for her broader aspiration, she says with a chuckle, “Do I think we will eliminate every last fee in my lifetime? Hope springs eternal.”

Ms. Stuhldreher is a little less sanguine. When asked about the future of the movement, she reflects, “I still feel like it’s early days, to be honest. There is momentum, but there is a lot more work to do.”

Mr. Atkinson concurs: “The road to abolition is long. We are trying to find as many strategic opportunities as possible to engage in harm reduction along the way.”

Many days in this work are hard and underwhelming. But Mr. Atkinson remembers one day that felt different.

His nonprofit, Forward Justice, had been working with the North Carolina district attorney’s office to think about how to get folks some relief. One in 12 adults in the state currently have unpaid criminal court debt, which often leads to a loss of their license and the vicious cycle that follows. Research shows that if people don’t pay in the first 24 months (likely because they can’t drive to work), they almost never do.

Durham County, North Carolina, District Attorney Satana Deberry decided that rather than using her prosecutorial resources to chase money that would likely never be found, she’d unleash people’s earning potential. On Jan. 14, 2019, she dismissed 559 fines in one fell swoop. She called it her “year of jubilee,” a biblical reference to a year of restoration. In the speech accompanying her decision, she said, “The main authority for my motions today is statutory. Yet, it is also ethical and fairer than the current arrangement, in [that] this debt largely burdens poor people. ... With their debts forgiven, these individuals can now get a driver’s license. They can get insurance. They can go to work and to school. They can participate fully in the economic and social vitality of our community.”

“That was a good day!” Mr. Atkinson recalls.

A small town, public art, and the First Amendment

Would no public art be better than art someone found objectionable? In New Hampshire, a town has been roiled for months over that question.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In front of the library on Main Street in Littleton, New Hampshire, is a bronze Pollyanna statue, smiling with her arms flung wide. Pollyanna’s carefree days may be numbered. If the residents of Littleton vote to limit public art, as one official has suggested, the statue will have to be removed. There’s no middle ground: Either all art or none would be allowed on government property.

Tucked just off Main Street are three boarded-up windows – now painted with nature scenes. The project was sponsored by a local organization, North Country Pride. Fearing future art with overt LGBTQ+ themes, one member of Littleton’s three-person select board raised objections to the painted panels, sparking a debate that has dragged on.

Disagreements over content, whether in art or in books, have been occurring across the United States, often resulting in bans. Art is protected by the First Amendment just as speech is, so censoring public art wouldn’t hold up, says Ken Paulson, director of the Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University.

“What we’re seeing nationwide is a pattern of legislators and city council members suddenly believing they have a license to regulate what people read or see,” says Mr. Paulson. “In many ways, it’s 1957 again in America.”

A small town, public art, and the First Amendment

In front of the library on Main Street in this northern New Hampshire town is a bronze Pollyanna statue, smiling with her arms flung wide. Pollyanna’s carefree days may be numbered. If the residents of Littleton vote to limit public art, as one Board of Selectmen member has suggested, the statue will have to be removed. There’s no middle ground: Either all art or none would be allowed on government property.

There’s no particular objection to Pollyanna herself. A few blocks away are the three paintings that sparked the debate over whether to limit public art. Tucked just off Main Street on the side of a building are three boarded-up windows – now painted with nature scenes. The project was sponsored by a local organization, North Country Pride. Fearing future art with overt LGBTQ+ themes, one member of the three-person select board raised objections to the painted panels late last summer, sparking a debate that has dragged on.

Disagreements over content, whether in art or in books, have been occurring across the United States, often resulting in bans covering school systems and libraries. In New Hampshire, what qualifies as art and the appropriateness of certain art have arisen in challenges to a lobster painting in Merrimack, a mural of baked goods in Conway, and the three panels in Littleton.

Art is protected by the First Amendment just as speech is, so censoring public art wouldn’t hold up, says Ken Paulson, director of the Free Speech Center at Middle Tennessee State University. Cities have one tool to control the appearance of public buildings, and that’s zoning. And while the government can decide what goes on its own buildings, it can’t outlaw art on private buildings or discriminate against ideas.

“What we’re seeing nationwide is a pattern of legislators and city council members suddenly believing they have a license to regulate what people read or see,” says Mr. Paulson. “So much of what’s going on now would have been unthinkable for decades. In many ways, it’s 1957 again in America.”

Littleton, a town of about 6,000 people, has a vibrant Main Street with local businesses, a music festival in the summer, and skiing in the winter. Unlike that of many small towns, the population is growing younger. Most residents shake their heads at the suggestion of limiting public art, particularly in the “Live Free or Die” state. Some suggest the crux of the issue is really a newcomer-versus-old-guard clash.

Selectwoman Carrie Gendreau, also a state senator, raised the objections to the murals. She has stated that many of her political views stem from her Christian faith, and used the word “demonic” to describe one of the panels in an interview with The Boston Globe. She did not respond to requests for comment.

The debate also reached the town’s theater, housed in a historic opera building on Main Street. Jim Gleason, the town’s manager until recently, says he heard objections from a handful of people to Theatre UP’s fall production, “La Cage aux Folles,” whose two main characters are gay. His response, he said in an in-person interview in late 2023, was that just as the theater is free to choose its plays, Littleton citizens are free to boycott the performances or protest from the street.

There were no protesters outside the opera house during any of the shows, according to Lynne Grigelevich, executive director of Theatre UP.

Some of the comments Mr. Gleason heard at the time took a personal turn. A woman who objected to the theater’s production told him she hoped his son was “in hell.” Mr. Gleason’s son, who died in 2016, was gay. “I wish this issue hadn’t come up and created the divide that it has in the community,” he says.

Mr. Gleason announced his resignation as town manager, effective Feb. 2, at a January meeting of the Littleton Board of Selectmen. Several days later, he told a local paper, he received an envelope containing a photo of himself with a homophobic slur written across it.

Local business owners and sisters Jessica and Rose Goldblatt were surprised by the objection to the art and the suggestion of a ban. Jessica recalled the case of a lighted cross on the mountain above the town in the 1980s, a symbol that was moved off public land. Now, faced with a new conversation about art, she says some of it may be due to changing dynamics within the community. “There’s a lot of young energy happening here,” she says, adding that she understands that for some longtime residents, it may feel like, “What’s happening to our town?”

Some of these changes are par for the course in the U.S., says Mr. Paulson.

“The impulse has always been there for the majority to protect its own culture and look askance at that of others,” he says. “The difference today is we live in the most diverse America ever, and those diverse communities are no longer willing to be silenced.”

A Littleton town meeting in September, available online, drew an estimated 300 people. It was far more than most residents could ever remember. One man, who introduced himself as Matthew Simon, used the public comment period to defend Ms. Gendreau. She “has served faithfully in this position, and she’s served and loved the members of this community with the same beliefs that she spoke of recently that many people share,” he said. He was met with shouts of objection when he said

Littleton residents had “tolerated” pride flags flying in the town.

“She speaks for the silent majority,” another commenter, Nick De Mayo, a Republican Party leader from Sugar Hill, said to mixed boos and applause. “Not only is Littleton a hub of this area; it’s also a religious hub of this area.”

Most people who spoke, however, agreed with Franco Rossi.

Mr. Rossi, who used to serve on the select board alongside Ms. Gendreau, said at the meeting he understands how difficult the job of town governance is, but that he can’t condone her actions.

“You certainly have the right to have your opinions and say what you want, but I don’t think you’re understanding what damage that does to a community that’s been marginalized for so long, that’s always been viewed as unequal,” he said.

Before he resigned, Mr. Gleason told the Monitor it was unlikely that a measure limiting public art would appear on the town warrant in the spring. That’s particularly true since the other two members of the select board have said they don’t support it. At the meeting where Mr. Gleason resigned, he suggested that the board may still ask the public to eventually weigh in on rules around art.

Tensions have extended to other areas of the community. “We were basically told that the entire Board of Selectmen did not agree with the LGBT lifestyle” in an October meeting, says Ms. Grigelevich, straining relationships between Theatre UP and the board. “Sometimes you’ve got to walk through the ugliness. ... I do think that much good will come of this.”

The controversy may ultimately have the opposite effect, says Kerri Harrington, a founder of North Country Pride. “People are saying, ‘Let’s do more art,’” she says.

That fits with her view of New Hampshire: “a libertarian stronghold,” “the state where you can go to try things out.” Mr. Gleason’s treatment, Ms. Harrington says in a January text message, has been disheartening.

The controversy could serve as a positive force for change, says Gregory Covell, a lifelong resident and an antique store co-owner. In fact, he says, it’s already bringing together a town that is becoming more diverse and younger.

“[Some people] still think it’s Mayberry, and that Sheriff Andy will solve everything, and it’s not,” he says. Littleton isn’t exempt from the complications facing the rest of the world, he adds, and “the leaders of the town aren’t sure how to respond to that. They’ve never been challenged like this.”

Books

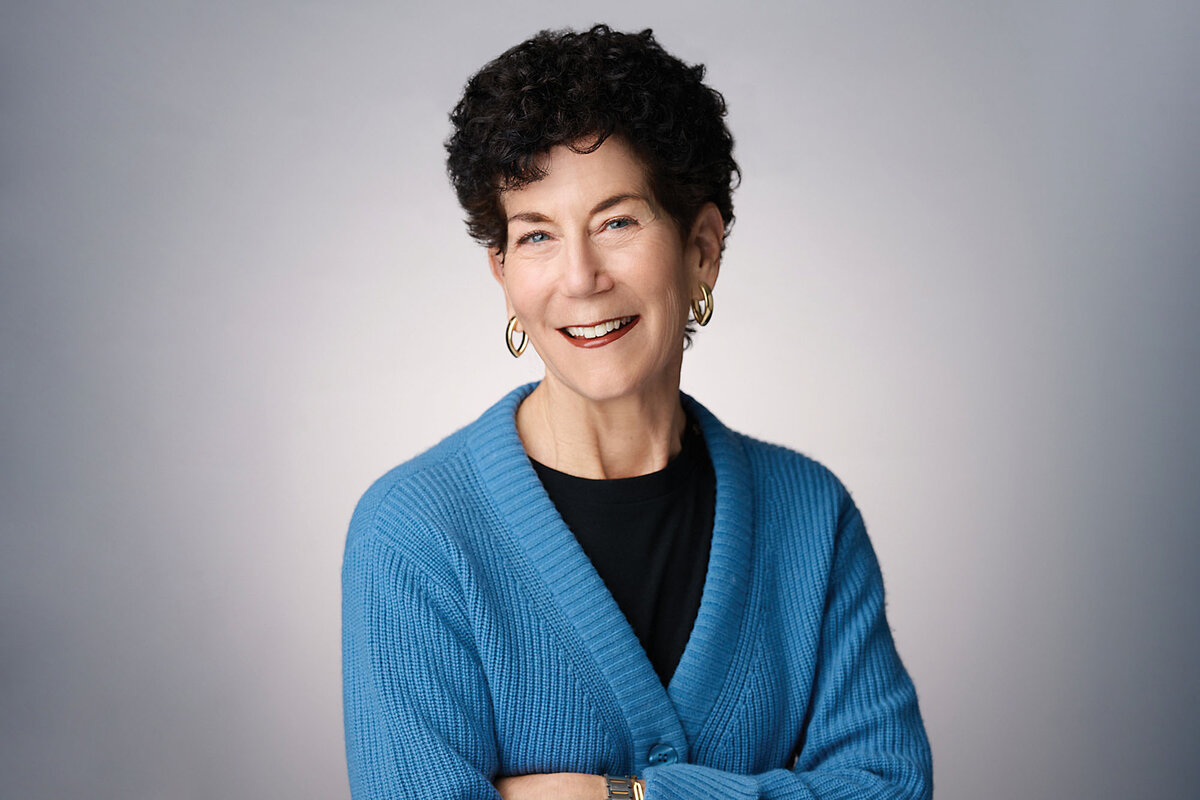

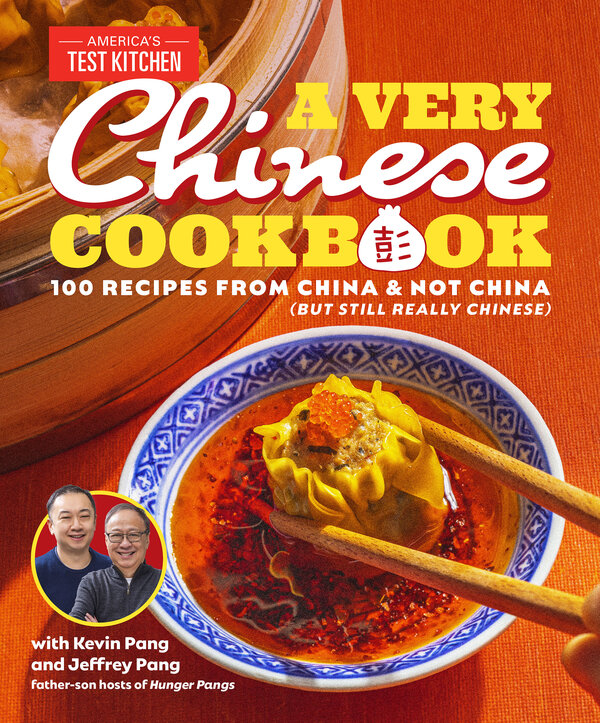

Father and son cooking duo stirs up Chinese cuisine

Food can bridge divides within families. Cooking dishes from their Chinese heritage, a father and son discover a shared language, and pass on that enthusiasm – with recipes! – to home cooks.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

The relationship between Jeffrey Pang and his son, Kevin Pang, was like hot-and-sour soup. It boiled over easily.

The Pangs, who immigrated to the United States in 1988, wanted their son and daughter to know Chinese culture. But as a sarcastic, video game-playing American teen, Kevin wasn’t interested. Learn to make his favorite Hong Kong-style Portuguese chicken, or radish cake for Lunar New Year? Forget it.

But when Kevin became a food writer for the Chicago Tribune, he realized he had a valuable resource: his wok-stirring dad.

“My father and I shared, for the first time, a mutual interest. I would call to ask about recipes and cooking techniques. He would school me on the world of Cantonese cuisine,” Kevin writes in the introduction to the cookbook he has just published with his dad, “A Very Chinese Cookbook: 100 Recipes From China & Not China (But Still Really Chinese)” from America’s Test Kitchen.

“When it comes to cooking Chinese food, there’s always been this barrier to entry. It’s way easier than people would think,” says Kevin.

Jeffrey says there is another lesson to be found between the pages of their cookbook.

“I think this cookbook can teach fathers and sons how to connect, how to find a common interest and remedy their relationship,” he says.

Father and son cooking duo stirs up Chinese cuisine

The relationship between Jeffrey Pang and his son, Kevin Pang, was like hot-and-sour soup. It boiled over easily.

The Pangs, who immigrated to the United States in 1988, wanted their son and daughter to know Chinese culture. But as a sarcastic, video game-playing American teen, Kevin wasn’t interested. Learn to make his favorite Hong Kong-style Portuguese chicken, or radish cake for Lunar New Year? Forget it. Once he left for college, conversations between father and son were brief.

But when Kevin became a food writer for the Chicago Tribune, he realized he had a valuable resource: his wok-stirring dad.

“My father and I shared, for the first time, a mutual interest. I would call to ask about recipes and cooking techniques. He would school me on the world of Cantonese cuisine,” Kevin writes in the introduction to the cookbook he has just published with his dad, “A Very Chinese Cookbook: 100 Recipes From China & Not China (But Still Really Chinese)” from America’s Test Kitchen.

Comparing notes on food slowly began to shrink the distance between them.

“Cooking is just like a bridge. It helps me pass on my mother’s home recipes to the next generation. That is very, very important to me,” says Jeffrey in a video interview from his home in Seattle.

Chinese food in the U.S. has evolved and adapted since the first wave of Chinese immigrants brought new tastes and cooking techniques to California in the mid-19th century. The cuisine survived the era of chop suey houses and anti-Chinese sentiment brought on by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. It has become a traditional Christmas dinner meal among many Jewish communities and a go-to takeout for busy weeknights. During Lunar New Year – this year from Feb. 10 to Feb. 24 – discovering the delight of soup dumplings is an urban trend. However, many people hesitate to re-create Chinese dishes at home.

“When it comes to cooking Chinese food, there’s always been this barrier to entry. It’s way easier than people would think,” says Kevin, speaking from his home in Chicago. For example, their recipe for cold sesame noodles comes together in 15 minutes using staple pantry items and leftovers.

He is quick to point out that there is no one definition of Chinese food.

“Chinese cooking is not a monolith. The food we grew up eating in Hong Kong, even within China itself, is very different from the food in Beijing, from the food in Shanghai,” says Kevin. “It’s a big tent cuisine.”

For example, consider baked pork chop rice, popularized in Hong Kong.

“It is a pork chop that’s been battered and fried and served with egg-fried rice. And then you top it with this thick tomato sauce that has peas, carrots, and onions,” explains Kevin. “And then you top that with Parmesan cheese. It’s a very interesting hybrid dish that has some Western British influences, and it’s altogether very Chinese as well.”

By the time Kevin joined America’s Test Kitchen staff in 2020 as its editorial director for digital content, his dad had become something of a YouTube sensation demonstrating the family’s recipes with his wife, Catherine. Kevin recognized an opportunity not only to share his own family’s food stories but also to apply the ATK method of breaking down recipes into simple steps for the home cook.

“They really let my father and I be the creative directors,” says Kevin. “It was very much a collaborative process, but at the end of the day, you had two Chinese guys who were able to say, ‘This is what we wanted out of a cookbook.’”

Jeffrey says the rigorous testing at ATK – one recipe can cost $11,000 to test and perfect – opened his eyes to new techniques and flavors, like adding oyster sauce to fried rice. He adds there is another lesson to be found between the pages of their cookbook.

“I think this cookbook can teach fathers and sons how to connect, how to find a common interest and remedy their relationship,” he says. That sentiment has found an enthusiastic fan base, generating nearly 3 million views, for their YouTube cooking series “Hunger Pangs,” where viewers gush over their father-son bond as much as they do over their enticing dishes.

Today the Pangs’ relationship is rarely sour or hot. “We’ve changed to sesame noodles,” says Jeffrey. “Cool, simple, easy.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Democracy’s foot soldiers in Pakistan

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

A little over a year ago, the departing head of Pakistan’s military, Gen. Qamar Javed Bajwa, closed out a long career on a rare note. “The time has come for all political stakeholders to set aside their ego” and take responsibility for their part in the country’s history of instability and corruption, he said. That call for humility and integrity in public service may have planted a mental seed that is now germinating in the outcome of last week’s national elections.

Voters defied the military’s efforts to bar politicians and parties it opposed. They are demanding the courts investigate evidence of ballot fraud. Women and youth in particular put individual agency and dignity before cynicism and despair.

The rise of civic participation among younger and female Pakistanis coincides with other trends reshaping a society striving for economic stability and accountable governance. Innovation is booming. The country’s technology sector posts record growth year after year.

The political parties must now forge a new government through consensus. “Voters have upset the games and the calculations of Pakistan’s political managers,” political analyst Nasim Zehra told the Monitor, referring to the military and its preferred political figures.

Democracy’s foot soldiers in Pakistan

A little over a year ago, the departing head of Pakistan’s military, Gen. Qamar Javed Bajwa, closed out a long career on a rare note. “The time has come for all political stakeholders to set aside their ego” and take responsibility for their part in the country’s history of instability and corruption, he said. “We need to reject this behaviour.”

That call for humility and integrity in public service may have planted a mental seed that is now germinating in the outcome of last week’s national elections. Voters defied the military’s efforts to bar politicians and parties it opposed. They are demanding the courts investigate evidence of ballot fraud. Women and youth in particular put individual agency and dignity before cynicism and despair.

“As a Pakistani, it was profoundly empowering to witness the collective outcry against injustice manifested through the ballot,” Hashim Ali Doger, a young voter from Lahore, told CNN. Another voter, Manahil Ahmed, said Pakistanis “have come to the one realization [they] previously had always struggled with, which is that all [political] power truly only rests in their will.”

Pakistan has a long history of democracy interference marked by corruption, family dynasties, and the military’s constant meddling in politics. Days before the Feb. 8 vote, former Prime Minister Imran Khan – already incarcerated on corruption charges widely held as politically motivated – and his wife were sentenced to 14 years in prison. The military’s favored candidate in 2018, he turned critical of the army’s influence in foreign policy and was ousted in 2022.

Mr. Khan and his party were barred from the elections last week. But he remains highly popular. Candidates from his party, running as independents, unexpectedly won 97 seats in parliament – well below the number needed to form a government outright, but significantly more than the military’s preferred parties.

Voter turnout was marginally lower than in 2018, according to official results released today. But of roughly 60 million who cast ballots (48% of all voters), 44% were under the age of 35. Mr. Khan’s party fielded 53 female candidates, the most of any party.

The rise of civic participation among younger and female Pakistanis coincides with other trends reshaping a society striving for economic stability and accountable governance. Innovation is booming. The country’s technology sector posts record growth year after year, driven by a population in which more than 64% are under the age of 30. Social media enabled Mr. Khan to boost voter enthusiasm from prison and were a bulwark against campaign disinformation.

On the governance side, constitutional reforms enacted in 2018 to empower local government have nurtured greater public confidence in democracy at the grassroots through transparency, improved services, and funding for civil-society groups.

The surprise outcome of last week’s vote has added momentum to that entrepreneurial and civic ferment. Pakistan’s political parties must now forge a new government through consensus and compromise. “Voters have upset the games and the calculations of Pakistan’s political managers,” political analyst Nasim Zehra told the Monitor, referring to the military and its preferred political figures. They are insisting on a future built on unity and integrity.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘Hey, Knucklehead’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Keith Wommack

God has given all of us divine authority over the temptation to sin.

‘Hey, Knucklehead’

Both sins and mistakes cause trouble. But a mistake is usually unintentional, whereas sin is a conscious act – intentional wrongdoing.

Mistakes can be corrected by knowledge or discernment. Sin, however, is eradicated by recognizing that our motives and actions were wrong and refusing to think or act in the same unloving, harmful, or self-destructive way. Several Bible accounts depict Jesus healing by exposing and destroying sin.

I learned an important lesson regarding the difference between a mistake and a sin a number of years ago when God caught my attention with the words, “Hey, Knucklehead.”

I was living in a peaceful neighborhood near a university when fraternity members moved in nearby. One night, they had a very noisy party. I tried to pray, but mostly grumbled as I tossed and turned.

Around four in the morning, I walked over to their back porch, turned off the music as they slept, then unplugged the still-blaring TV and carried it to my house. I got the peace and quiet I wanted, but as I was about to fall asleep, I heard “Hey, Knucklehead, get up! You stole your neighbor’s TV. You broke God’s Commandment!”

While God sees His children as the pure reflection of His perfection, this truth manifests itself in ways we can understand. Sometimes it feels like a mighty rebuke, even though God’s messages are benign. The contrast between the pure goodness of God and that which is not expressive of it can be jolting.

Humbled, I returned the TV and came home, transformed. I’d believed I was a victim of another’s self-indulgence, but I realized that I had sinned. I had selfishly indulged in a false sense that God’s children could be a disturbance and that I was justified in taking matters into my own hands. I saw that, instead, I had to do my part to see everyone (including myself) as God has created us. Even though I’d felt wronged, I couldn’t engage in sinful thinking or acts that left Spirit, God, out of the picture.

After that, the nearby house became quieter. No other party disturbed me while I lived in that area.

Sin includes thinking of ourselves and others as mortal, flawed, and inclined to err, when in reality Spirit made us spiritual, immortal, and wholly good. A mortal way of thinking causes us to live in small, limited, zero-sum ways. It accepts God as less than good and ever-present and as incapable of caring for our needs. Essentially, sin is thinking and acting in a self-centered, destructive, or unloving way.

Though sin isn’t the same as a mistake, both are wrong. The more we understand Spirit and our true nature, the fewer mistakes we’ll make and the greater dominion we’ll have over temptation.

This requires honest self-examination, as the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, wrote in an address. She added, “Even a mild mistake must be seen as a mistake, in order to be corrected; how much more, then, should one’s sins be seen and repented of, before they can be reduced to their native nothingness!” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 109).

Where do we begin in the effort to overcome sin? Human will cannot do it. Christ, Truth, the divine idea of God demonstrated so completely by Jesus, empowers it. First, we must know what we really are: the spiritual offspring or self-expression of Spirit, made to reflect divine goodness and grace. Second, we must recognize the weaknesses and sins that we have been accepting as a part of our nature.

Then we can prayerfully reason with the truth to remove these aggressive lies and be redeemed from past mistakes. God, speaking through a faithful prophet, yet directly to each of us, stated, “Forget the former things; do not dwell on the past. See, I am doing a new thing! Now it springs up; do you not perceive it?” (Isaiah 43:18, 19, New International Version).

We express God, divine Mind, as Mind’s conscious, holy, spiritual ideas, and so are able to recognize mistakes and sinful temptations quickly, correct them, and boldly and safely move on. Instead of acting like knuckleheads, we can accept our spiritual selfhood and live freely without fear and disappointment.

Since that night all those years ago, I’m usually quicker at utilizing spiritual might over temptations to indulge in selfish, sinful thoughts. I have striven to see everyone as God-made – and therefore spiritual, loved and loving, wise and considerate – and to know that we can all act accordingly. Through prayer, we allow Christ to dissolve sin, correct mistakes, and reveal the freedom and joy of spiritual being.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Feb. 5, 2024, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

A Mahomes moment

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us as you start your week. Tomorrow, please come back for a close look at the many serious considerations swirling around Israel’s stated intention to invade Rafah, in the Gaza Strip.