To many outsiders, Myanmar appears to be locked in a bloody stalemate. The ongoing civil war has killed more than 4,000 people and left 2.6 million displaced within the country, according to United Nations estimates. Every third person – about 18.6 million people – now requires humanitarian aid, a nineteenfold increase since the February 2021 military coup that overthrew Myanmar’s elected government.

But as the war enters its fourth year, there are signs of a shift.

This weekend, the junta announced that it would start enforcing a 14-year-old compulsory military service law, effective immediately. The draft comes as Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, the country’s military ruler and architect of the 2021 coup, faces calls to step down after a wave of humiliating losses to allied resistance groups.

Indeed, the military has lost control of scores of towns and military bases in recent months. These advances don’t necessarily spell victory for Myanmar rebels, but they are weighing on the junta – and reinvigorating the resistance.

Where have the rebels made gains?

The junta faces many enemies, including pro-democracy groups formed by civilians after the coup and various armed ethnic groups that have long fought for autonomy. Historically, these different groups have fought alone, planning attacks and negotiating cease-fires in relative isolation.

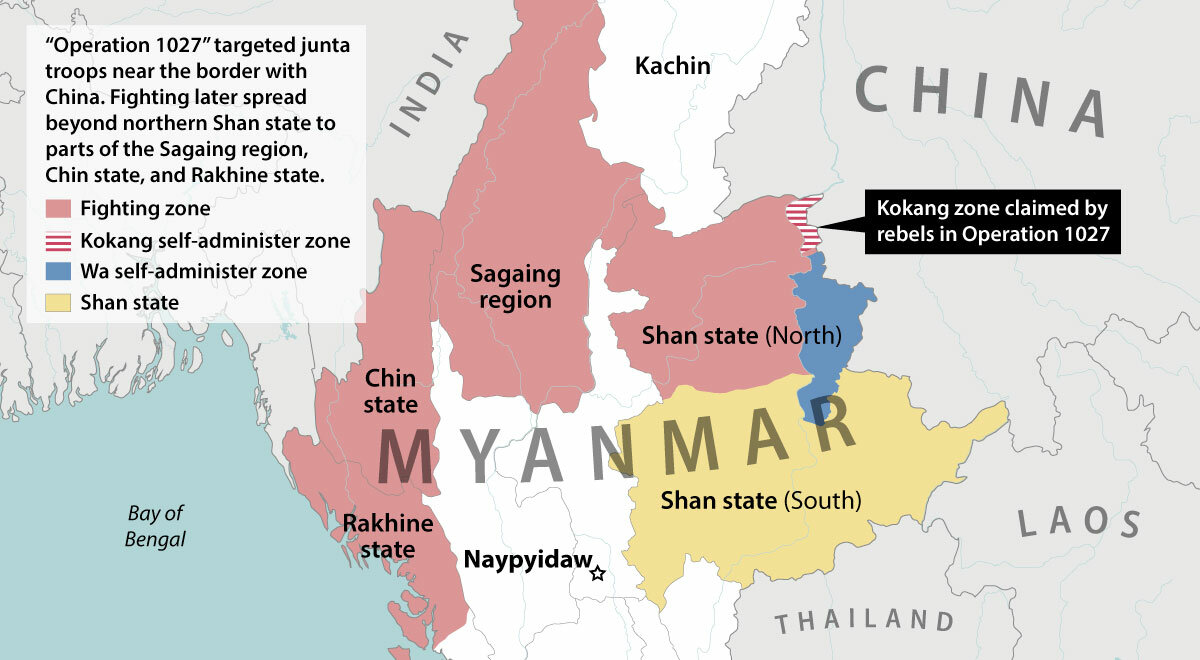

The status quo started to shift in October, when three insurgent groups known as the Three Brotherhood Alliance launched “Operation 1027” to take on junta troops in northern Shan state near the border with China. Analysts say the operation had tacit backing from Beijing, which wanted to punish the junta over its failure to curb online scams operating out of Myanmar. The campaign was incredibly successful. Within days, the alliance captured more than 50 junta bases and shut down major border crossings.

Other armed groups, including the Chin National Army, supported the operation by launching attacks around their own areas of control, forcing the junta to respond on multiple fronts. As the parallel offensives gained momentum, the junta witnessed some demoralizing defeats. In late January, hundreds of junta soldiers fled across the border to India, and many more have surrendered in the face of bold ground and drone attacks.

The National Unity Government, an anti-junta body that oversees many of the newer civilian groups, claims that junta opponents now control 60% of the country. That control remains largely peripheral, with rebels failing to claim a single central city or major military infrastructure.

What challenges do resistance groups face?

While resistance groups have demonstrated their ability to mount coordinated attacks, they are still fractured and lack a central command. Most work for their own goals, which do not necessarily resonate with other groups.

“The resistance is faced with the difficult task of crafting a shared political vision,” says Angshuman Choudhury, a former associate fellow at the Centre for Policy Research in New Delhi. “This is not an easy task in a country with hundreds of ethnic groups and subgroups.”

On top of that, fighters continue to deal with ammunition and weapons shortages, whereas the junta has critical access to heavy weapons, mainly from Russian suppliers. Nevertheless, resistance leaders say there will be more surprise strikes against the junta this year.

“The resistance groups have never been so strong against the junta,” says Ram Kulh Cung, a Chin National Army commander. “There is some sort of coordination between the resistance groups, and we are working towards making it better and much stronger with one aim – to throw the junta out of power and restore democracy.”

How is the junta responding?

Despite growing frustration among the ranks, the junta is not giving up.

Militarily, its focus “has been to both reclaim fallen towns and degrade resistance assets,” says Mr. Choudhury. “It continues to rely on airstrikes and artillery offensives against civilian populations in order to cut them off from the resistance groups. It has also adopted an online counterpropaganda program to discredit the resistance among the masses.”

How the junta is responding internally is less clear. The junta has not addressed criticism directly, but it did activate the military draft and extend Myanmar’s state of emergency for another six months to restore “a normal state of stability and peace,” according to a military-run media outlet. This confers Gen. Min Aung Hlaing legislative, judicial, and executive powers and will further delay elections. Yet with Gen. Min Aung Hlaing at his weakest position since the coup, some speculate that he could be replaced with another senior military officer.

What is evident, say analysts, is that the junta is doing damage control, and hope for rebel victory – and postwar stability – rests on its opponents’ ability to continue cooperating.