- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Being seen, being heard

In Israel, women want to be seen in a new light. In France, women are working to be heard in a new way.

The circumstances are very different. But two stories today share a common theme.

Israeli women point to wartime work not only as solo family leaders or advocates, but as combat soldiers – a recent role for them. French women are challenging an adulation of male French film icons that brushes aside sexual abuse allegations piling up around them. However gradually, these women are shifting perceptions, pressing against limitations, and breaking down roadblocks. They’re changing the broader conversation about equality.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Meet Sora: AI-created videos test public trust

OpenAI’s Sora, a text-to-video tool still in the testing phase, has set off alarm bells, threatening to widen society’s social trust deficit. How can people know what to believe, when they “can’t believe their eyes”?

In a world where artificial intelligence can conjure up fake photos and now videos, it’s hard to know what to believe. The announcement of the AI film creator Sora has set off alarm bells in media circles.

Technologists, meanwhile, are trying to mitigate the problem. Several companies are embedding codes that distinguish between AI-generated photos and the real thing. Courts have also grappled with how to distinguish fake videos.

But the social trust deficit remains daunting. OpenAI has not yet released its video technology for Sora, except to outside testers to figure out how to guard against misuse.

The technology could prove a boon to artists, film directors, and ad agencies, offering outlets for creativity and speeding up the productions. The challenge lies with those who might use the technology unscrupulously – and with oversight, given the volume of fake videos that might be produced.

Photojournalists will also have to adapt, says Brian Palmer, a photographer based in Richmond, Virginia. For more than 30 years, he says, he’s been trying to represent people honestly. Recently, he posted a code of ethics on his website, which starts, “I do not and will not use generative artificial intelligence in my photography and journalism.”

Meet Sora: AI-created videos test public trust

In a world where artificial intelligence can conjure up fake photos and videos, it’s getting hard to know what to believe.

Will photos of crime-scene evidence or videos of authoritarian crackdowns, such as China’s Tiananmen Square or police brutality, pack the same punch they once did? Will trust in the media, already low, erode even more?

Such questions became more urgent earlier this month when OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, announced Sora. This AI system allows anyone to generate short videos. There’s no camera needed. Just type in a few descriptive words or phrases, and voilà, they turn into realistic-looking, but entirely computer-generated, videos.

The announcement of Sora, which is still in the testing phase, has set off alarm bells in some circles of digital media.

“This is the thing that used to be able to transcend divisions because the photograph would certify that this is what happened,” says Fred Ritchin, former picture editor of The New York Times Magazine and author of “The Synthetic Eye: Photography Transformed in the Age of AI,” a book due out this fall.

“The guy getting attacked by a German shepherd in the Civil Rights Movement was getting attacked. You could argue, were the police correct or not correct to do what they did? But you had a starting point. We don’t have that anymore,” he says.

Technologists are hard at work trying to mitigate the problem. Prodded by the Biden administration, several big tech companies have agreed to embed technologies to help people tell the difference between AI-generated photos and the real thing. The legal system has already grappled with fake videos for high-profile celebrities. But the social trust deficit, in which large segments of citizens disbelieve their governments, courts, scientists, and news organizations, could widen.

“We need to find a way to regain trust, and this is the big one,” says Hany Farid, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley and pioneer in digital forensics and image analysis. “We’re not having a debate anymore about the role of taxes, the role of religion, the role of international affairs. We’re arguing about whether two plus two is four. ... I don’t even know how to have that conversation.”

While the public has spent decades struggling with digitally manipulated photos, Sora’s video-creation abilities represent a new challenge.

“The change is not in the ability to manipulate images,” says Kathleen Hall Jamieson, a communication professor and director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania. “The change is the ability to manipulate images in ways that make things seem more real than the real artifact itself.”

The technology isn’t there yet, but it is intriguing. In samples released by OpenAI, a video of puppies playing in the snow looks real enough, another shows three gray wolf pups that morph into a half-dozen as they frolic, and an AI-generated “grandmother” blows on birthday candles that don’t go out.

While the samples were shared online, OpenAI has not yet released Sora publicly, except to a small group of outside testers.

A boon to creative minds

The technology could prove a boon to artists, film directors, and ad agencies, offering new outlets for creativity and speeding up the process of producing human-generated video.

The challenge lies with those who might use the technology unscrupulously. The immediate problem may prove to be the sheer number of videos produced with the help of generative AI tools like Sora.

“It increases the scale and sophistication of the fake video problem, and that will cause both a lot of misplaced trust in false information and eventually a lot of distrust of media generally,” Mark Lemley, law professor and director of the Stanford Program in Law, Science and Technology, writes in an email. “It will also produce a number of cases, but I think the current legal system is well-equipped to handle them.”

Such concerns are not limited to the United States.

“It’s definitely a world problem,” says Omar Al-Ghazzi, professor of media and communications at the London School of Economics. But it’s wrong to think that the technology will affect everyone in the same way, he adds. “A lot of critical technological research shows this, that it is those marginalized, disempowered, disenfranchised communities who will actually be most affected negatively,” particularly because authoritarian regimes are keen to use such technologies to manipulate public opinion.

In Western democracies, too, a key question is, who will control the technology?

Governments can’t properly regulate it anytime soon because they don’t have the expertise, says Professor Hall Jamieson of the Annenberg Center.

Combating disinformation

The European Union has enacted the Digital Markets and Digital Services acts to combat disinformation. Among other things, these acts set out rules for digital platforms and protections for online users. The U.S. is taking a more hands-off approach.

In July, the Biden administration announced that OpenAI and other large tech companies had voluntarily agreed to use watermarking and other technologies to ensure people could detect when AI had enhanced or produced an image. Many digital ethicists worry that self-regulation won’t work.

“That can all be a step in the right direction,” says Brent Mittelstadt, professor and director of research at the Oxford Internet Institute at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. But “as an alternative to hard regulation? Absolutely not. It does not work.”

Consumers also have to become savvier about distinguishing real from fake videos. And they will, if the Adobe Photoshop experience is any guide, says Sarah Newman, director of art and education at Berkman Klein Center’s metaLAB at Harvard, which explores digital art and humanities.

Three decades ago, when Photoshop began popularizing the idea of still photo manipulation, many people would have been confused by a photo of Donald Trump kissing Russian President Vladimir Putin, she says. Today, they would dismiss it as an obvious fake. The same savvy will come in time for fake videos, Ms. Newman predicts.

Photojournalists will also have to adapt, says Brian Palmer, a longtime freelance photographer based in Richmond, Virginia. “We journalists have to give people a reason to believe and understand that we are using this technology as a useful tool and not as a weapon.”

For more than 30 years, he says, he’s been trying to represent people honestly. “I thought that spoke for itself. It doesn’t anymore.” So, a couple of months ago, he put up on his website a personal code of ethics, which starts, “I do not and will not use generative artificial intelligence in my photography and journalism.”

Today’s news briefs

• Sweden clears NATO hurdle: Hungary’s parliament votes to ratify Sweden’s bid to join NATO, bringing an end to more than 18 months of delays that have frustrated the alliance as it seeks to expand in response to Russia’s war in Ukraine.

• U.S. airman’s Israel protest: An active-duty member of the U.S. Air Force dies after he set himself ablaze outside the Israeli Embassy in Washington, while declaring that he “will no longer be complicit in genocide.”

• Palestinian prime minister resigns: Palestinian Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh says he is stepping down to allow for the formation of a broad consensus among Palestinians about political arrangements following Israel’s war against Hamas.

• GOP leader steps down: Republican Party chairwoman Ronna McDaniel says she is leaving the job after weeks of public pressure from the party’s likely 2024 presidential candidate, Donald Trump.

Israeli women rise to war’s challenges

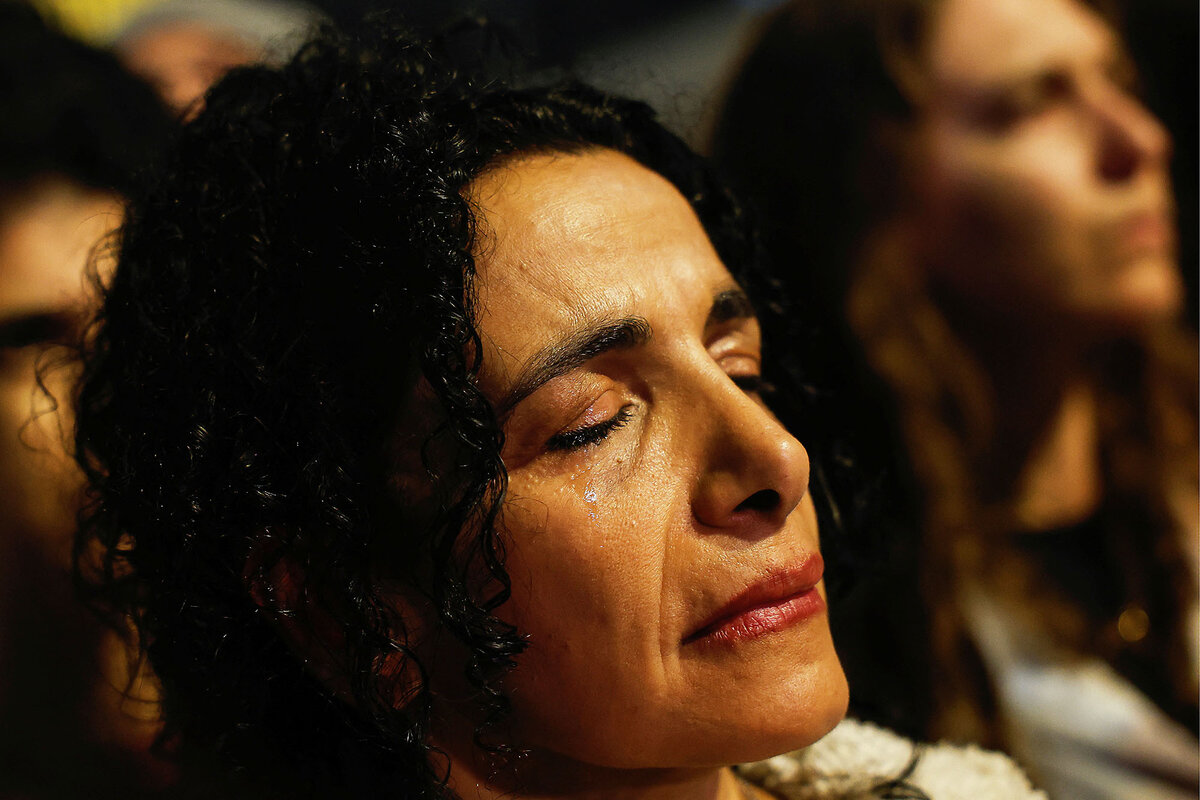

Months after protesters marched in Tel Aviv dressed as handmaidens to thwart an attempted judicial overhaul by the far-right government, Israeli women are shifting perceptions of gender roles as they serve on the front lines of the war effort.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

As Israel grapples with war and trauma, women’s rights advocates say the conflict may serve as a turning point in society’s views of women’s roles. Israeli women are fighting in the army, taking care of displaced people, and pushing for justice or freedom for those killed or captured.

When soldiers Lea and Alejandra, two friends who are in ongoing operations on the ground in Gaza, volunteered for combat duty, they say they were seeking to prove their strength, “test themselves,” and break the “stereotypes that only men can do combat.”

On Oct. 7, Alejandra’s home community was among several overrun and attacked by Hamas; friends and neighbors were killed.

“They came in and took our friends, our cousins, our mothers, our grandmothers,” Lea says. “It is very personal.”

Before the war, Israeli society was debating whether women should serve in combat. Now “the debate is over,” the soldiers say. Approval is expressed not only in their peers’ respect, but also in being stopped and thanked by strangers on buses, on the street, and in grocery stores.

“People are starting to understand that we are really strong and can do our job and they need us,” Lea says.

Israeli women rise to war’s challenges

Mother, sister, survivor, peacemaker, healer, soldier – Israeli women are playing many roles in the Israel-Hamas war, with their country requiring more from them than ever.

Just as Palestinian women are carrying an outsize burden in the besieged Gaza Strip, so, too, are women in Israel, who are fighting in the army, taking care of displaced people, and pushing for justice or freedom for those killed or captured.

As Israel grapples with war and trauma, women’s rights advocates say the conflict may serve as a turning point in society’s views of their roles, especially as soldiers in combat.

Gender has been a central element of the war since it was sparked by the Oct. 7 attack, in which Hamas reportedly employed systematic sexual and gender-based violence on a scale unknown in the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Just months after protesters marched in Tel Aviv dressed as handmaidens – decrying the far-right government’s attempted judicial overhaul they feared would curb women’s rights – Israeli women were at the front lines of the war effort.

Call to arms

Women have long been drafted into the Israel Defense Forces, but the majority traditionally have served in administrative, support, or training positions.

When Lea and Alejandra enlisted in 2022 and early 2023, they were among the first female conscripts to sign up for combat duty since Israel’s Supreme Court received a series of petitions in 2020 challenging the IDF’s exclusion of women from fighting roles.

The pair, who asked to withhold their full names for security reasons, say they were seeking to prove their strength, “test themselves,” and break the “stereotypes that only men can do combat.”

Yet they never expected to be testing themselves in war – let alone a war that “is personal.”

Their unit, Field Intelligence Unit 414, was among the first to fight Hamas when their base was overrun Oct. 7. Lea and Alejandra were on a nearby base; friends and fellow female soldiers were killed by Hamas militants.

An all-women tank company attached to a mixed-gender infantry battalion helped repel the attack, and it was female intelligence officers who alerted superiors of the raid.

“We are very proud of that, because they played a really strong role in that day – there are so many stories of girls that did everything they could and fought to stop the advance,” Alejandra, fresh from returning from Gaza and on a short leave in Israel, says via a WhatsApp call. “We are proud of how they put their fear aside.”

Alejandra’s home community was among several southern kibbutzim overrun and attacked by Hamas; friends and neighbors were killed.

“They came in and took our friends, our cousins, our mothers, our grandmothers,” Lea says. “It is very personal.”

The two of them, like hundreds of women now serving in combat units, are in ongoing combat and intelligence operations on the ground in Gaza, where they know “there is a chance we might die,” Lea says.

They say a source of courage is serving alongside female recruits they had bonded with over harsh training sessions in the desert, including 17-mile hikes and grueling several-mile marches carrying another recruit over their shoulders.

“I know that we have each other’s backs and we won’t leave anyone behind,” Alejandra says.

In Israel’s pre-Oct. 7 debate over women serving in combat roles in mixed-gender units, resistance was especially strong on the far-right and in some religious establishments.

In a November 2022 poll by the Jerusalem-based Israel Democracy Institute, 53% of Israelis supported women serving in combat roles, with 35% against.

Now, more than a year later, with record numbers of women serving in combat units, “the debate is over,” the soldiers say. Approval is expressed not only in their peers’ respect, but also in being stopped and thanked by strangers on buses, on the street, and in grocery stores.

Families

Women are also serving on the home front.

Thousands of families were displaced from southern Israel and along the northern border by fighting and missiles in the first two weeks of the war. Months later, more than 200,000 Israelis unable to return home still live in hotels and hostels across the country.

Many women are heading single-parent households as their conscripted partners serve in Gaza or on the Lebanese border, or train for deployment.

In a Tel Aviv hotel, Noa’s two daughters play in the lobby as she makes a call to her parents outside Jerusalem. The real estate agent was vacated from her northern border kibbutz and now, with her husband serving in Gaza, has to balance getting her children to a nursery, working remotely, and navigating Tel Aviv far from family.

“This is our sacrifice,” Noa says as she scrambles after the younger daughter, who wandered out the door and onto the sidewalk. “The terrorists want to break us as a nation, as communities and as families. By holding our families together, we are defeating them.”

With the government ill-prepared to provide social services to the thousands of displaced civilians following Oct. 7, civil society and nongovernmental organizations stepped in to help provide trauma support, counseling, and even basics such as clothes and food.

Women’s rights advocates cite low representation at the top of the Israeli government as hindering its ability to provide family services for displaced people. Six of Israel’s 32 government ministers are women, and none sit in the influential wartime Cabinet; one female minister serves in the security Cabinet.

Fight for justice

Last week, the Hostages and Missing Families Forum provided the International Criminal Court in The Hague with 1,000 pages of testimony from released hostages and eyewitnesses, along with forensic evidence, alleging torture, gender-based violence, and sexual violence by Hamas.

It was the latest in a campaign by families led by mothers, sisters, and forensics and legal experts to pressure for hostages’ releases and have Hamas’ leadership tried for war crimes.

Leading Israeli women rights and legal experts are assisting the campaign and coordinating with United Nations’ special rapporteurs on torture and sexual violence to build a legal case.

“My goal is to have Oct. 7 go down in history side by side with those previous cases of weaponizing women and sexual violence in war such as Bosnia, Rwanda, and the DRC [Democratic Republic of Congo],” says Ruth Halperin-Kaddari, an expert in gender studies and international law and director of the Rackman Center for the Advancement of the Status of Women at Bar-Ilan University.

As members of the Civil Commission on October 7 Crimes by Hamas Against Women and Children, Professor Halperin-Kaddari and others are documenting crimes and reaching out to experts in gender-based violence used as a tactic in previous wars.

“It is needed for Israeli society at large. I think this recognition is important in terms of recovery from the collective trauma,” she says.

From civil society volunteers to the army, more women are pitching in.

Recent women draftees’ requests to join Alejandra and Lea’s Field Intelligence Unit 414 were 133% of the outfit’s capacity. The figure for the Artillery Corps was 132%. Among all women, 12% requested to serve in active fighting roles.

“I really think people are starting to understand that we women are strong and can do the job,” Lea, the soldier, says, “and they need us.”

Why French cinema’s sexual abuse problem persists

Auteurs and actors are held in high esteem in France. That may be in part why the country is still wrestling with sexual abuse scandals involving some of its cinematic leading lights.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Gérard Depardieu is one of the iconic actors of French cinema. But Mr. Depardieu has more recently gained notoriety as a sexual predator.

More than a dozen women have accused the actor of sexual assault or harassment, and he is accused of raping a woman in 2018. In December, the actor’s fall from grace seemed complete after a broadcast of the documentary “Depardieu: The Fall of an Ogre,” which records the actor making sexist remarks.

But two weeks later, despite widespread condemnation, 56 stars of French cinema signed an open letter on his behalf. French President Emmanuel Macron defended the actor on national television, saying Mr. Depardieu had “made France proud.”

With all of the progress made by the #MeToo movement in allowing victims of sexual violence to be heard, why does it seem that French people are more willing to extend their trust to their cinematic icons instead of those who accuse them?

“This myth of seduction, which is widespread among France’s cultural elite, is without a doubt responsible for our refusal to realize that masculine domination is an integral part of social relations, even in the private sphere,” says Geneviève Sellier, professor emeritus of film studies, “and a reason why France was so late on #MeToo.”

Why French cinema’s sexual abuse problem persists

For many American filmgoers, actor Gérard Depardieu is one of the iconic faces of French cinema, known for his leading role in “Cyrano de Bergerac” or for playing Dominique Strauss-Kahn in the 2014 film “Welcome to New York.”

But Mr. Depardieu has more recently gained notoriety as a sexual predator. More than a dozen women have accused the actor of sexual assault or harassment, and he is accused of raping a woman in 2018.

In December, the actor’s fall from grace seemed complete after a television broadcast of the documentary “Depardieu: The Fall of an Ogre,” in which the actor was seen making sexist remarks while in North Korea in 2018.

But two weeks later, despite widespread condemnation, 56 stars of French cinema signed an open letter on his behalf. French President Emmanuel Macron defended the actor on national television, saying Mr. Depardieu had “made France proud” with his past cultural contributions. And Mr. Depardieu’s former agent called the actor “a monster, yes, but ... a sacred monster.”

It’s an issue not limited to Mr. Depardieu. The presentation of the César Awards, France’s top cinematic honors, on Friday were dominated by a speech by actor Judith Godrèche, in which she condemned the “level of impunity, denial, and privilege” in French cinema. Ms. Godrèche, now 51 years old, has accused two directors, Benoît Jacquot and Jacques Doillon, of sexually assaulting her while she was a teenager and they were both decades older. Both men have denied doing anything illegal, but it is only recently that their behavior has come under public scrutiny.

With all of the progress made by the #MeToo movement in allowing victims of sexual violence to be heard, why does it seem that French people are more willing to extend their trust to their cinematic icons instead of those who accuse them?

“The trend is moving towards listening to victims, but it still remains one person’s word over another,” says Bruno Pequignot, a sociologist and professor emeritus of arts and culture at the Sorbonne Nouvelle University in Paris. “Meanwhile, there is a feeling that cinema stars exist above the common man, that their behavior lies outside the norm.”

“The artistic cult”

French actors have enjoyed a special star status since the 18th century. But starting in the 1950s and with the advent of the “film d’auteur” – films that reflected their director’s artistic personality – directors also began enjoying a unique place in the hearts and minds of the French.

Films themselves were soon granted “artistic legitimacy” and equated with intellectual creation – likened to works of art or literature – and their directors, usually men, elevated to the status of demigods, living outside checks and balances. That has endured and been extended to creative minds across the pond such as Woody Allen or Quentin Tarantino, as well as films’ leading men.

“The religious cult in France has been replaced by the artistic cult,” says Geneviève Sellier, professor emeritus of film studies at Bordeaux Montaigne University. “There is a vision of the male genius who is given free rein to express himself, the artist who exists outside of the law.”

But some say that power has allowed French male film stars and directors to engage in borderline criminal behavior in the name of artistic creation. Industry insiders say there is often an element of seduction starting from the audition process and an expectation for young actresses to have physical relations with directors to accelerate their careers.

Thus, situations in which life imitates art – even when inappropriate – become more commonplace and thus tolerated, both on set and in the public eye.

“This is an industry that exists outside of societal norms,” says Fatima Benomar, the president of the women’s rights organization Coudes à Coudes. “A minor might kiss an older man in a film or have a nude scene, and it’s acceptable because it’s in the name of art, but obviously in real life, these things are illegal. So already they don’t obey the same rules.”

What makes this situation uniquely French, says Dr. Sellier, is partly due to a controversial theory by historian Mona Ozouf that in France, men and women must obey a “code of seduction,” as opposed to America’s “war of the sexes.”

“This myth of seduction, which is widespread among France’s cultural elite, is without a doubt responsible for our refusal to realize that masculine domination is an integral part of social relations, even in the private sphere,” says Dr. Sellier, “and a reason why France was so late on #MeToo.”

Incremental change

Still, the 2017 #MeToo movement has had a positive effect in breaking the code of silence surrounding sexual abuse in the industry. Filmmaker Christophe Ruggia was indicted on charges of sexual assault of a 15-year-old minor, following accusations by actor Adèle Haenel. And the industry has seen an increase in female directors and roles for strong female characters.

“There will always be narcissistic perverts in the industry, but we must be careful not to stigmatize all directors,” says Jonathan Broda, a film historian at the International Film & Television School of Paris. “I’m really in favor of education and respect. I always tell my female students to be on guard, keep their senses, and rise above.”

But women’s rights groups point to roadblocks that have made trusting sexual assault victims over their accusers more difficult in France. In addition to the special status France’s cultural male elite enjoy in their ability to promote the country’s soft power, says Dr. Sellier, French celebrities can also count on an exceedingly slow legal system.

Around 80% of rape cases are dismissed, and fewer than 1% end in a conviction, according to France’s High Council on Equality Between Women and Men. Though a 2018 law has helped better punish sexual harassment, sexual violence, and sexism, President Macron has refused to define rape as nonconsensual sex, in line with 11 other European countries.

“It’s hugely important for the government to be behind [sexual harassment and abuse] laws in order to create new societal norms,” says Violaine de Filippis Abate, a lawyer and activist with the nonprofit Osez le Féminisme. “There is still far too much ordinary sexism, as well as this idea that when a woman complains, she’s just exaggerating, that ‘it’s not that bad.’”

Oftentimes, media investigations have been more successful in unofficially “trying” French celebrities accused of sexual abuse in the absence of a formal legal decision. Figures like acclaimed film director Luc Besson – accused of rape in 2018 – have escaped a public lynching. And only time will tell the long-term effect Ms. Godrèche’s comments at the César Awards had. But Mr. Depardieu’s latest comments seem to have been one offense too many.

Several actors have since removed their signatures from the letter defending Mr. Depardieu. And though Mr. Macron did not retract his comments, he seemed to have realized their political toll, telling French journalists weeks later that he should have spoken up in the name of victims’ plight.

“In the case of Depardieu, the public has taken the law into its own hands, and he has been found guilty,” says Mr. Pequignot, the sociologist. “I think, if nothing else, going forward his case has strengthened the power of victims’ ability to be heard.”

Editor's note: The story was updated to clarify what Christophe Ruggia was indicted for.

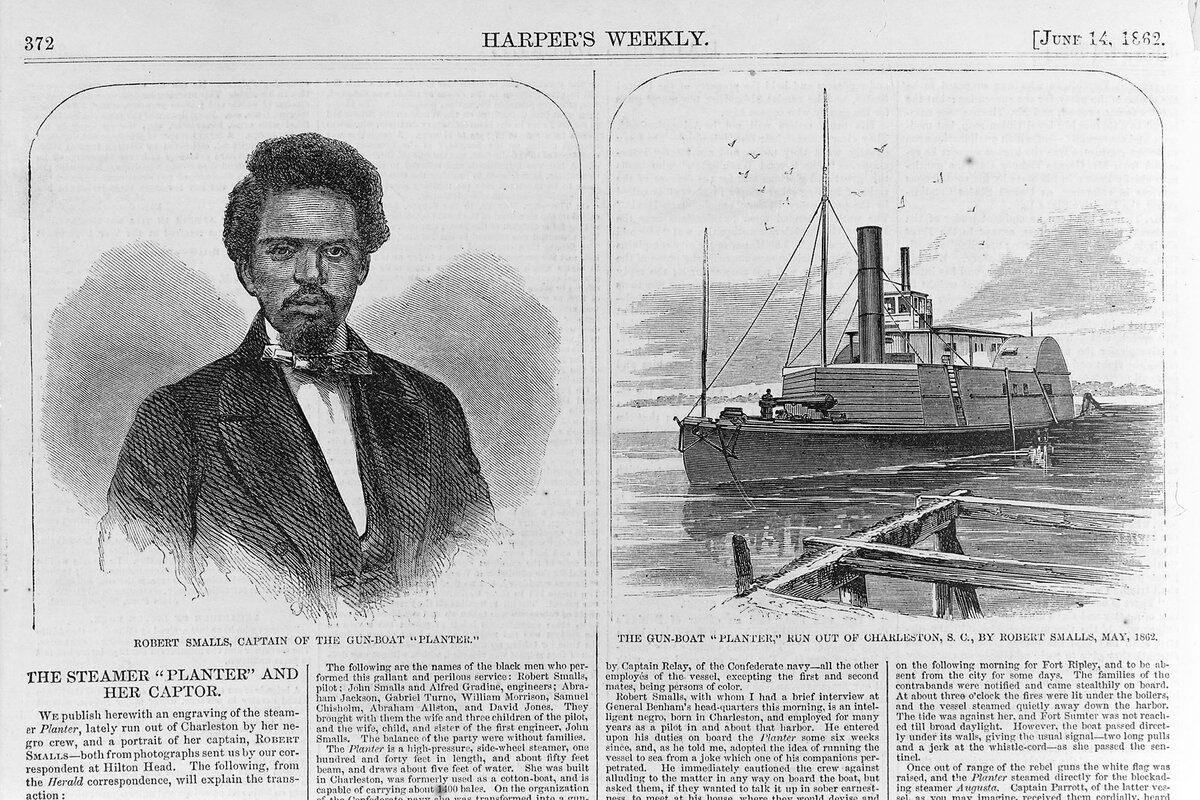

Robert Smalls: Why isn’t he a household name?

The founder of the first free public schools in the U.S. was born enslaved and won freedom not only for himself, but also his family, by commandeering a Confederate gunship. Why isn’t he as famous as Harriet Tubman?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The life and legacy of Robert Smalls are the stuff of a made-for-TV movie.

There’s the thrilling seizure of a Confederate ship, a literal vessel of freedom for a man born into slavery. His political career after the Civil War – first in the South Carolina statehouse and then in the halls of Congress in Washington – resulted in a legacy of free public education for all U.S. schoolchildren.

Legion M is planning a graphic novel of Smalls’ story, with the hope of turning it into a feature film or TV series. The idea to bring his story to a larger audience was a no-brainer, explains Rob Edwards, a screenwriter for Disney’s Academy Award-nominated “The Princess and the Frog.”

“The more I researched into his life, the more I realized this man never bowed down from a challenge. The odds were always against him incredibly. And he was like, ‘Who else is gonna do this?’” Mr. Edwards says in a phone interview. “That’s why you need to tell the story now. ... We’re fighting for the same things that we were fighting for then.”

Robert Smalls: Why isn’t he a household name?

The life and legacy of Robert Smalls are the stuff of a made-for-TV movie. There’s the thrilling seizure of a Confederate ship, a literal vessel of freedom for a man born into slavery. His political career after the Civil War – first in the South Carolina statehouse and then in the halls of Congress in Washington – resulted in a legacy of free public education for all U.S. schoolchildren.

In a different world, Smalls would be a household name, mentioned in the same breath as Barack Obama and Harriet Tubman.

Last summer, that different world was the San Diego Comic-Con.

Outside of the San Diego Convention Center, rebellion was in the air. Outside, the writers’ strike was at a fever pitch. Inside, an idea that began as a Kickstarter had manifested itself into a panel defined by a single word – DEFIANT.

Legion M was planning a graphic novel of Smalls’ story, with the hope of turning it into a feature film or TV series.

The idea to bring Smalls’ story to a larger audience was a no-brainer, explained Rob Edwards, a screenwriter for Disney’s Academy Award-nominated “The Princess and the Frog.” He was speaking on a panel that included one of Smalls’ direct descendants, Michael Boulware Moore, and actor and rapper Marvin “Krondon” Jones III.

“The more I researched into his life, the more I realized this man never bowed down from a challenge. The odds were always against him incredibly. And he was like, ‘Who else is gonna do this?’” Mr. Edwards said in a phone interview after Comic-Con. “That’s why you need to tell the story now. … We’re fighting for the same things that we were fighting for then.”

Smalls taught himself how to read and write after he won his freedom. In 1868, during the South Carolina Constitutional Convention, Smalls and an unprecedented majority of Black legislators crafted a policy that created the country’s first free public schools for all children. “All the public schools, colleges, and universities of this State supported by the public funds shall be free and open to all the children and youths of the State, without regard to race or color” was the phrasing drafted in the state’s constitution.

Smalls’ life stands in opposition to all the people claiming Reconstruction was a failure because “‘these people’ do not have the intellectual, mental, cultural ability to govern themselves,” says Bobby Donaldson, an associate professor at the University of South Carolina, who leads the school’s Center for Civil Rights History and Research. “Now, the crazy thing about that is Robert Smalls is almost a symbolic image of that sort of defiance. ... Here was someone who physically challenged all the narratives that were being thrown at Black people – that they lacked the capacity to fight, they lacked the capacity to serve, and they lacked the capacity to govern. And here’s Robert Smalls standing tall saying, I beg to differ.”

Capture of the CSS Planter

In April 1861, the Civil War began in Charleston with The Battle of Fort Sumter. The following fall, Smalls was assigned to steer an armed Confederate ship named the CSS Planter. In May 1862, Smalls planned his daring escape from slavery.

After he donned the captain’s apparel and picked up his family and the families of his enslaved crewmates, he guided the ship past five Confederate harbor forts, giving the correct steam-whistle signals at checkpoints. One last barrier remained to freedom: Smalls and his crew of seven had to sail past Fort Sumter, the most heavily guarded of the Confederate forts.

“At about 4:15 a.m., the Planter finally neared the formidable Fort Sumter, whose massive walls towered ominously about 50 feet above the water. Those on board the Planter were terrified. The only one not outwardly affected by fear was Smalls,” the Smithsonian Magazine wrote. “As the Planter approached the fort, Smalls, wearing [the captain’s] straw hat, pulled the whistle cord, offering ‘two long blows and a short one.’ It was the Confederate signal required to pass, which Smalls knew from earlier trips as a member of the Planter’s crew.”

As the Planter approached the Union Army, there was still the matter of a Confederate gunboat closing the gap on “enemy” quarters. That’s where Smalls’ wife, Hannah, came in. Her savvy use of a white sheet to replace the Confederate flag created a makeshift flag of surrender. The Smalls had secured their own freedom and freedom for 14 others.

A likeness of the Planter rests in Mitchelville Freedom Park on Hilton Head Island, which Luana Graves Sellars, an activist and the founder of Lowcountry Gullah, frequents often.

“His story is not just a story of someone escaping slavery. His story is about courage, determination,” Ms. Sellars says in a phone interview. “It’s about assimilating into a new society. It’s about sharing his skills towards the efforts of the Civil War being fought. It’s about the reconstruction of America, and it’s about grace.”

That grace was exemplified in a story that Ms. Sellars recounts in an online biography of Smalls. Many years after he secured his freedom, Smalls housed the family that enslaved him.

“After the war, and his distinguished service to both the U.S. Army and the U.S. Navy, Smalls returned to Beaufort, SC where at a tax sale, he bought the home that had been owned by the McKee family, his former owners,” Ms. Sellars’ account reads. The family was destitute. “In an extraordinary demonstration of a kind and forgiving heart, he allowed members of the McKee family to continue living in the house. Remarkably, he even allowed the matriarch, who had become senile, to continue to believe that she was still lady of the house until her death.”

For all Smalls’ swashbuckling efforts, his humanity is what endures, Ms. Sellars says.

“It reminds me of an African proverb – ubuntu – which means ‘I am because we are.’ I think that really embodies Robert Smalls and his legacy in that he knew that his work and his legacy could not just stop with him, that it needed to be part of the greater good for everyone,” she says.

Another stunning part of Smalls’ legacy? His proximity to literary giants such as Frederick Douglass and W.E.B. Du Bois.

“In 1888, there’s a journalist who comes to Augusta and he talks about how quickly we forget history intentionally. He may even mention Robert Smalls and how people erase the promise of Reconstruction. ... The reporter was a man named Frederick Douglass,” Dr. Donaldson says. “And then he says that it is the obligation of Black people to challenge that history and to keep it alive.”

Mr. Edwards, the screenwriter, understands that folks won’t be reading the graphic novel or watching a film based on “dusty old history.” The goal is to present how a man named Smalls was larger than life.

“I always say the most heroic thing [Smalls] did was die of old age,” Mr. Edwards says. “He commandeered the Planter, and he had a bounty on his head,” that would be worth about $125,000 in today’s dollars. “Four thousand dollars for anybody who took him out, and that was the bounty placed on his head when he was 23. And still, he just passed away [at age 75] in his sleep.”

Essay

The actor, the ironing board, and an unlikely lesson

Things rarely go according to plan. Understanding the art of improvisation – whether on stage or in life – enables us to dance with the surprises, mishaps, and pivots that life often presents.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Owen Thomas Contributor

It was opening night of our middle school production of “Half a Sixpence.” My buddy John and I were seventh grade stagehands. Lisa was an eighth grade star. And I admire her to this day for a moment that had little to do with the play itself. It had to do with an ironing board.

The auditorium filled with families, friends, and faculty. The lights dimmed; John and I rushed onstage with the props. As the scene opens, Lisa’s character stands at an ironing board, ironing.

There was a problem.

“Guys!” Lisa hissed. She had the iron in one hand and was supporting the ironing board with the other. “It won’t stay up! Guys!”

We had but seconds. John and I made futile efforts to fix it. The lights were coming up – as were the hairs at the back of my neck. We had to go! We plunged down the steps, abandoning her. “So glad it’s not me up there!” I thought guiltily.

Poor Lisa was up there, clutching the ironing board and gamely pushing the iron back and forth. In seconds, she would have to cross the stage to her love interest. What would she do? What could she do?

The actor, the ironing board, and an unlikely lesson

No one succeeded in persuading my teenage self that I’d come to see things differently. Every generation, I now realize, shakes its head knowingly at the rising one, having been the object of such head-shaking itself. Some early life events – breakups, bad grades, unfortunate wardrobe choices – seem to need time to settle into perspective. “You’ll see,” say clueless adults. We disagree – until we catch ourselves saying exactly that to a skeptical teen.

A female lead in my middle school’s musical can probably relate. Lisa was an eighth grade star. I was a seventh grade stagehand. And I admire her to this day for a moment that had little to do with the play itself. It had to do with an ironing board.

My buddy John and I were asked to be stagehands – the only seventh graders in an eighth grade production. We were stationed in front of the curtain on stairs that led to the floor of the auditorium. We crouched on the steps, racing onstage when the lights dimmed between scenes to position and retrieve props. I have no idea how a middle school production of “Half a Sixpence” struck those with more sophisticated tastes. But as a middle schooler, I was impressed. It was a huge deal.

Lines were learned, songs perfected, stagecraft honed. John and I hit all our marks. Dress rehearsal had gone well, and now it was opening night. The auditorium filled with families, friends, and faculty. Most of the school was there.

“Half a Sixpence” centers on Arthur Kipps, a draper’s assistant who unexpectedly inherits a fortune. Ann is his childhood sweetheart, but upper-class Helen falls for him, too – and her mother has designs on Artie’s wealth. Artie must choose. The climactic scene takes place when Artie encounters Ann, played by Lisa. As the scene opens, she stands at an ironing board, ironing.

The lights dimmed prior to that scene. John and I rushed onstage with the props.

There was a problem.

“Guys!” Lisa hissed. She had the iron in one hand and was supporting the ironing board with the other. “It won’t stay up! Guys!”

We had but seconds. John and I made futile efforts to fix it. No good. The lights were coming up – as were the hairs at the back of my neck. We had to go! We plunged down the steps, abandoning her. “So glad it’s not me up there!” I thought guiltily.

Poor Lisa was up there, though, clutching the ironing board and gamely pushing the iron back and forth. In seconds, she would have to say, “Oh, Artie!” and cross the stage to where he stood. What would she do? What could she do?

Here’s what she didn’t do. She did not:

• Gently lower the ironing board to the floor and step over it to go to Artie. That would have been odd.

• Walk over to Artie carrying the ironing board and iron and continue the scene as though nothing was wrong. That would have been odd and unintentionally comic.

• Stay put and yell her lines to the childhood sweetheart with whom she was reconciling. That would have been disturbingly odd.

Instead, Lisa showed great poise. She stayed in character and added a brilliant bit of stage business, having had but a handful of heartbeats to decide. What would you have done?

“Oh, Artie!” she exclaimed. Then she simply let go. Ironing board and iron fell with a crash that served to amplify the emotion of the moment. It was comic. It was dramatic. The audience loved it. She’d saved herself, the performance, and two shaken seventh graders.

Had she made a different choice, anguish might have trailed her memory of that evening. Instead, it was a triumph, a life lesson that I didn’t come to appreciate fully until much later.

What could be more disheartening than a spectacular fail in front of the whole school, with a literal spotlight on you? And what could be more empowering than to turn a potential train wreck into an ingenious bit of improv?

One of the rules of improv is “Play in the present and use the moment.” Or, in Lisa’s case, “Use what you’re given – even if it’s broken.”

Thanks, Lisa! I see it now: You showed me how it’s done.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Peaceful steps to defang gangs

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For Caribbean leaders gathering this week to discuss how to end rule by gangs in Haiti, a lesson might be found from a truce brokered in Mexico between warring drug cartels over the weekend: The best solution may lie in discerning the motives of those caught up in violence.

There are people in gangs and drug cartels who “no longer want war, they no longer want to be killing each other,” said Salvador Rangel, a retired Catholic bishop in Guerrero, the southern Mexican state where the two cartels overlap. It is crucial, he said, “to take advantage of that desire to bring peace.”

Across Latin America, countries are trying different tactics against a rise of nonstate violent groups. In Mexico, the truce in Guerrero arose from efforts by local religious leaders to break the violence and extortion disrupting the lives of ordinary citizens. Four bishops held meetings with leaders from the two cartels. It seemed neither side was willing to budge, so the bishops backed off. Then, on Saturday, the groups announced a breakthrough on their own.

Peaceful steps to defang gangs

For Caribbean leaders gathering this week to discuss how to end rule by gangs in Haiti, a lesson might be found from a truce brokered in Mexico between warring drug cartels over the weekend: The best solution may lie in discerning the motives of those caught up in violence.

There are people in gangs and drug cartels who “no longer want war, they no longer want to be killing each other,” said Salvador Rangel, a retired Catholic bishop in Guerrero, the southern Mexican state where the two cartels overlap. It is crucial, he told The Associated Press, “to take advantage of that desire to bring peace.”

Across Latin America, countries are trying different tactics against a rise of nonstate violent groups. In Colombia, for example, the city of Buenaventura has become the center for government efforts to neutralize armed militias and other illicit groups since the two predominant gangs there declared a truce in 2022. The city’s homicide rate has dropped while civic participation among women and youth has increased. As a visiting delegation of the United Nations Security Council noted, “Lack of economic and educational opportunities continue to make young people vulnerable to recruitment by armed groups,” but they are also learning to see themselves as “not only victims, but also agents of change.”

In Mexico, the truce in Guerrero arose from efforts by local religious leaders to break the violence and extortion disrupting the lives of ordinary citizens. Four bishops held meetings with leaders from the two cartels. It seemed neither side was willing to budge, so the bishops backed off. Then, on Saturday, the groups announced a breakthrough on their own.

They haven’t said what changed their minds. But as a 2013 InSight Crime study of gang truces in Latin America noted, agreement reached between rival illicit groups – either directly or through civic mediators – is often built on establishing enough trust to promote further confidence-building and “verification of commitments.”

In Haiti, which has been without an elected government since the 2021 assassination of its prime minister, the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect estimates that 2 million people live in areas controlled by more than 200 different criminal groups. International efforts to send a peacekeeping force are aimed at restoring calm so that elections can be held.

More countries in Latin America realize that challenging gangs with either arms or arrests does not always work. “You cannot confront violence with violence, you cannot put out fire with fire,” Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador said this month. “You must confront evil by doing good.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The blind men and the elephant

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Karen Neff

When we’re willing to look beyond personal, material perspectives and consider things through a spiritual lens, we get a clearer, truer, and healing view.

The blind men and the elephant

In the allegory of the blind men and the elephant, a group of men who cannot see, and who have never come across an elephant before, learn and imagine what an elephant is like by touching it. Each man feels a different part of the animal’s body, such as the trunk or a tusk. They then discuss the animal based on their limited experience.

But their descriptions of the elephant are different from each other. Soon they come to suspect each other as dishonest, and they come to blows (see “Blind men and an elephant,” wikipedia.org). The story illustrates the idea that if we claim absolute truth based on our own personal, limited experience, we may miss out on knowing the whole picture.

I’ve found this story helpful in thinking about politically charged election seasons, when differing opinions may cause anger and confrontation to flare up. Division may arise when our conclusions don’t mesh with another’s. We may wonder what those holding different opinions could possibly be thinking.

At times like this it can be helpful to consider where we’re drawing our conclusions about other people or situations from. In my study and practice of Christian Science I’ve seen how turning to God, Spirit, for inspiration and truth brings the clearest, most healing view.

Christian Science teaches that God alone is all-knowing and all-seeing. God knows everything that’s good and true about His children. God knows us not as combative mortals, but as His spiritual offspring, reflecting Him in every way. Christ, the divine ideal that Jesus demonstrated, enables each of us to know the pure, spiritual man of the divine Mind’s knowing – even seeing that in another holding a differing opinion.

In “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, writes, “Reasoning from cause to effect in the Science of Mind, we begin with Mind, which must be understood through the idea which expresses it and cannot be learned from its opposite, matter. Thus we arrive at Truth, or intelligence, which evolves its own unerring idea and never can be coordinate with human illusions” (pp. 467-468).

As we look to God, infinite Mind, to define us, we grow into the understanding of everyone’s divine right and ability to express intelligence and kindness. We no longer feel we need to force an issue with others and get them to see things our way, but are charitable and kind as we realize that relying on the physical senses clouds our view of divine Truth and Spirit. Blindness can be viewing our fellow men and women from a limited, material perspective. It is like forming an opinion of someone by looking through a straw – it can only give limited information.

But we can trust that our heavenly Father loves and guides us in knowing everyone’s true, spiritual, intelligent, loving nature as His children. God gives us all the capacity to gather the spiritual facts of existence when we turn to Him in prayer. That’s not to say we all must have the same opinions. But it causes us to come to just and equitable conclusions, to overcome fear of an unfavorable outcome, and to resist the pull of anger and reactiveness that leads to confusion and upheaval. In this way we can contribute to harmony and progress even when confronted with opposing opinions.

At one point, an election to fill a particular office was being held at my church. I was convinced that I was the right person to fill the position, and arrived at the meeting ready to accept the nomination. However, I was not elected.

It turned out that I did not know best. Not only did completely unforeseen circumstances mean that I was no longer available to fill the position by the time it was to begin, but also, the person who had been elected did an excellent job. The outcome blessed us all, and showed that pride is not the most useful lens to look through.

We don’t have to hold to rigid opinions based on a limited, material view of the world around us. Instead we can let spiritual sense inspire us to continue to love our neighbors – even those we disagree with – the way Christ Jesus taught. We can trust that God is here to lead all of us to answers that bless.

Viewfinder

Eager to fly

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us at the start of your week. We have many engaging stories coming your way, so please keep checking in. Tomorrow, we’ll help you figure out what to read next with our 10 best books of February – including a selection by longtime former Monitor contributor David Montero.