- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- In deterrence we trust? Cold War nuclear questions make a comeback.

- Today’s news briefs

- Student protests dominate the news. For most young voters, a different issue is No. 1.

- Facing Russian threat and an uncertain America, Europe rearms

- Flight delayed? Air traffic control woes go beyond what FAA bill would fix.

- Stories of resilience: Bees make a comeback, and immigrants help economies

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A proliferation of trust?

“Mutually assured destruction” was an ominous Cold War slogan promoting the idea of peace through nuclear firepower. The ultimate existential standoff.

The world still has its potential nuke-slingers. Does a worst-case worldview still make sense? What does deterrence call for today, as big powers bristle and rogue notions rise? Is trust-building around threats and promises possible? Anna Mulrine Grobe and Sarah Matusek look at the new calculus.

Relatedly, in his Patterns column, Ned Temko looks at how concerns about U.S. isolationism and Russian aggression have Europe thinking about agency and autonomy in defense – about trust, about mutually assured preservation.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In deterrence we trust? Cold War nuclear questions make a comeback.

The risks of nuclear weapons have reappeared in global headlines. Containing those risks may hinge on transparency and communication as well as a “peace through strength” tradition.

-

Sarah Matusek Staff writer

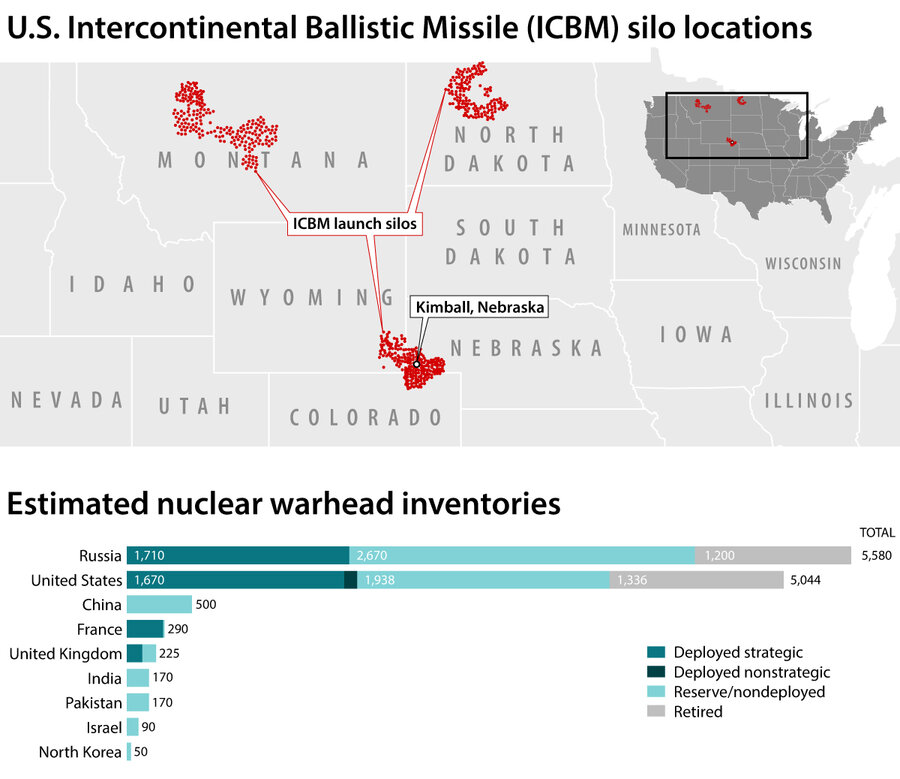

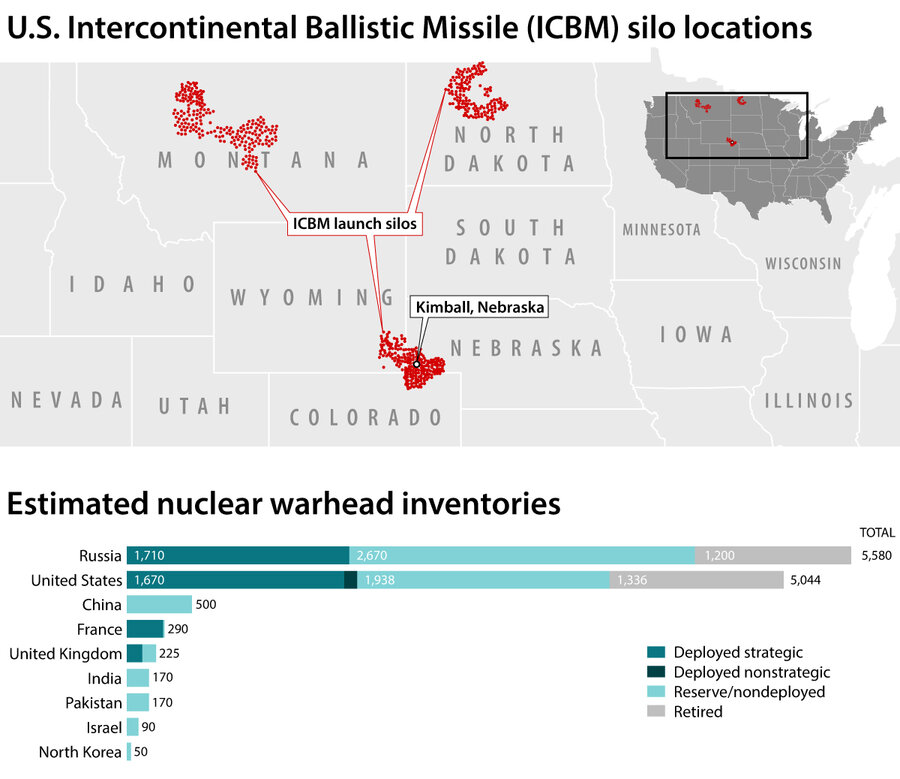

The Cold War never fully thawed in the single-stoplight town of Kimball, Nebraska. Nuclear weapons lie scattered beneath the high plains here. Up to 400 of these intercontinental ballistic missiles, or ICBMs, remain on alert across the rural West.

Some outsiders may see Kimball as a sacrifice. Rich Flores calls his community “patriotic.”

“The people here, in my opinion, believe that we have ‘peace through strength,’” says Mr. Flores, a county commissioner, echoing a line popularized by President Ronald Reagan. “Who wants to attack a country that’s strong?”

This is the logic of deterrence in a nutshell. Though the staggering cost of a coming missile upgrade in this region has ignited discussion about the necessity of America’s vast nuclear arsenal, the fact that the nation hasn’t used these weapons since World War II seems to deepen, for many, trust in their necessity.

But as global conflicts involving nuclear powers escalate, this trust is being tested. In Kimball and beyond, questions about America’s nuclear strategy are taking on more urgency as rhetoric about the likelihood of a nuclear attack is on the rise.

In deterrence we trust? Cold War nuclear questions make a comeback.

The Cold War never fully thawed in this single-stoplight town, nestled in a county of fewer than 4,000 people that seems built for a populace twice its size. Empty storefronts tell that story of six decades ago, when the nuclear missiles moved in.

The weapons lie scattered beneath the high plains here – some a few miles from a school. Up to 400 of these intercontinental ballistic missiles, or ICBMs, remain on alert in rural parts of the American West, ready to launch at the president’s call.

Some outsiders may see Kimball as a sacrifice. Rich Flores calls his community “patriotic.”

“The people here, in my opinion, believe that we have ‘peace through strength,’” says Mr. Flores, a county commissioner, echoing a line popularized by President Ronald Reagan. As he chats over coffee, an American flag pin glints from his chest.

“Who wants to attack a country that’s strong?”

This is the logic of deterrence in a nutshell. Though the staggering cost of an upcoming missile upgrade in this region has ignited discussion about the necessity of America’s vast nuclear arsenal, the fact that the nation hasn’t used these weapons since World War II seems to deepen, for many, trust in their necessity.

But as global conflicts involving nuclear powers escalate, this trust is being tested. In Kimball and beyond, questions about America’s nuclear strategy – and how people feel about it – are taking on more urgency as concern about the likelihood of a nuclear attack is on the rise.

Senior U.S. military officials describe the world’s nuclear landscape as “breathtaking” in its potential for escalation. The United States, they warn, is now on the verge of having not one but two nuclear “peer” adversaries, as the Department of Defense calls them. China’s rapid buildup of its nuclear forces means it could have at least as many ICBMs as either the U.S. or Russia by the decade’s end, analysts say. Russian President Vladimir Putin is expanding his nuclear arsenal and rattling these sabers toward the West in his war against Ukraine.

As a result, the U.S. now faces threats that it “did not anticipate and for which it is not prepared,” a bipartisan commission appointed by Congress concluded last autumn.

While risk of a “major nuclear conflict remains low,” the nation needs to “urgently” prepare to take on adversaries who want to impose undemocratic values on the free world, according to the report.

Part of that preparation will occur around Kimball, which is set to see nearby missile fields upgraded over the next decade with a new weapon system called Sentinel.

Advocates for nonproliferation say America has more than enough nuclear weapons to deter opponents. Their imperative, rather, is reopening communication lines – laying the groundwork for lapsing or nonexistent arms control agreements – to restore a sense of safety and trust in what can seem like a precarious time. And some see promising developments along these lines.

“One of the most important things that we can do is to head off unconstrained nuclear competition between the U.S., Russia, and China,” says Daryl Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association.

“Taboos against nuclear weapons still exist,” he adds, “and each generation needs to ensure they’re not broken.”

American trust in nuclear weapons

In the nearly 80 years since the U.S. dropped the only two nuclear weapons ever used in war, movements to abolish or champion nukes have ebbed and flowed.

Currently, Americans grapple with mixed views about the country’s nuclear weapons. A Chicago Council-Carnegie Corporation survey last year showed that 47% of U.S. adults believe the nuclear arsenal makes the U.S. safer. (Older adults are more likely than younger adults to say this.)

Moreover, China and Russia aren’t the only countries that worry Americans, who rank the development of nuclear programs in Iran and North Korea as two of the top three “critical threats” to the U.S., according to Gallup.

As U.S. leaders face a public that’s conflicted about trusting in deterrence, better communicating the country’s nuclear capabilities, some say, could help.

Nuclear nonchalance or confidence?

Retired Gen. John Hyten, who had been serving as vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff since 2019, recalls receiving a July 2021 phone call “so important that I went running to” the chairman and the secretary of defense after hanging up.

It was top-secret news of “the most significant launch that had happened during my lifetime”: a Chinese hypersonic missile designed to elude U.S. detection systems and potentially be used as a first-strike weapon in a nuclear war.

It threatened the land-based leg of the U.S. nuclear triad, which is composed of ICBMs, like those kept around Kimball, as well as stealth bombers and nuclear-armed submarines.

General Hyten spent the last three months of his tenure working to get news of China’s hypersonic missile declassified, he said in a February discussion at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center.

In November 2021, he got the Pentagon green light to air his concerns on CBS News. The sense after the broadcast was that it was going to “create a ruckus in this country like nobody’s seen before,” he recalled. “And like three days later, it had disappeared from the news.”

He grapples with nuclear nonchalance in America, but admires the general trust that citizens seem to have in the government’s ability to keep them safe.

“You know, I actually want to be the citizen of a country where people ... don’t worry about this stuff. They go to bed at night, and they sleep like babies,” he said. “But somebody’s got to think about it.”

Feeling like a target

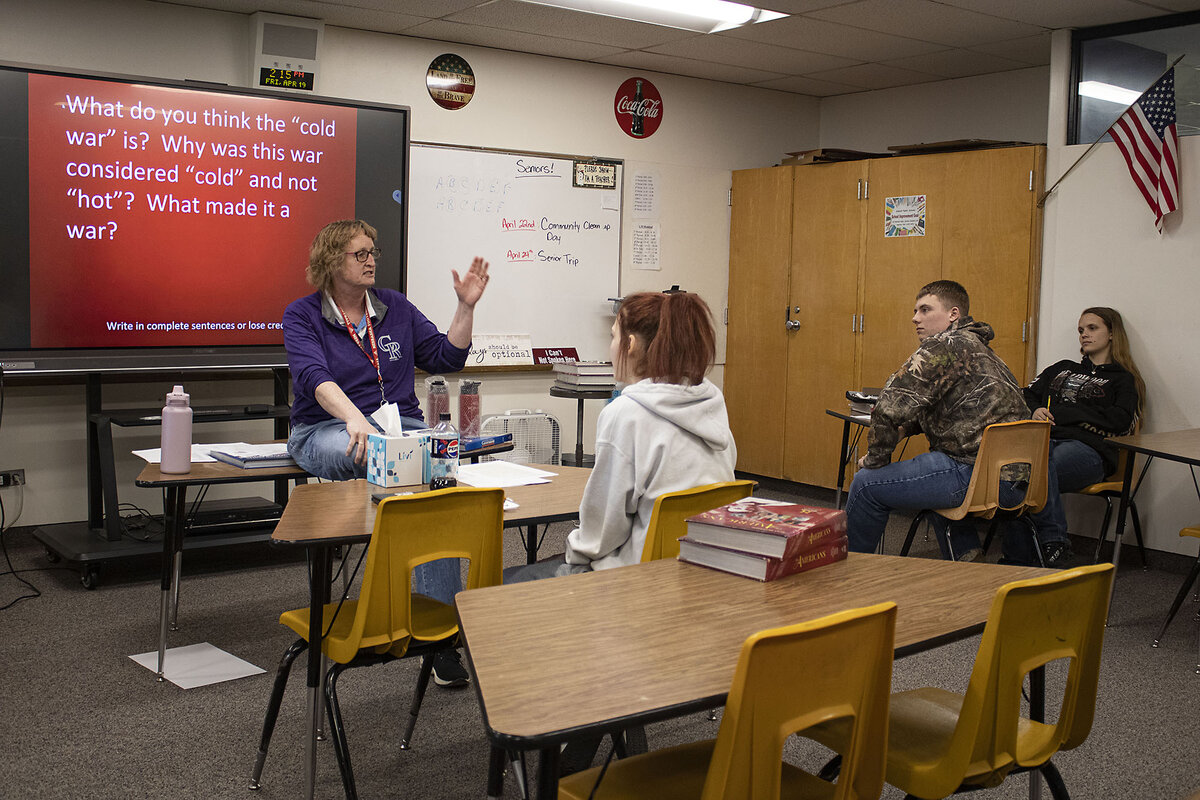

As a high school social studies teacher in Kimball, Jeri Ferguson is one of those people who thinks about the question of trust in nuclear arms. She recalls safety-in-numbers logic that could evoke either confidence or unease during the Cold War.

“I was in my car, driving in college, and with the radio on: ‘Russia has enough nuclear weapons to kill us four times over. But we have enough to kill them 10 times over,’” she recalls. “I remember thinking, ‘Once is probably enough for me!’”

On a recent afternoon, Ms. Ferguson began a unit on that history with a class of seven juniors.

“What do you think the Cold War was about?” she asks the group. “Global warming?”

No, the class groans, and volleys back more jokes. It was about “power,” says a boy. “During the winter!”

The teacher turns the focus closer to home – the Sentinel upgrade that could swell the local population with workers. The class seems vaguely aware of the missile silos scattered across the county.

“If there’s a nuclear war, guess where the first bombs are coming?”

“Us,” a student says. The jokes hit pause.

Restoring transparency – and talking to each other

The renewed conversation about nuclear arms in America points to a tension between the fear these devastating weapons inspire and the belief that the country wouldn’t be safe without them.

These are concerns that hint at the importance of bolstering transparency and communication to build trust not just in the weapons but among humans, too.

The global nuclear stockpile has declined significantly since the Cold War, from roughly 70,300 warheads in 1986 to some 12,100 in 2024, the Federation of American Scientists estimates. But most of these reductions happened in the 1990s. Since then, the pace has slowed.

Transparency is also on the decline. While the U.S. used to make its stockpile size public, this stopped under the Trump presidency. The Biden administration restored these disclosures at first, but then suspended them again.

While it’s difficult to know precise reasons the government is now refusing declassification requests, it may be that the transparency is politically difficult to justify given Russian and Chinese opacity, says Matt Korda, senior research fellow in the Nuclear Information Project at the federation.

The State Department, in a written response to the Monitor, said that declassification “does not occur on a planned calendar” and that the “value of transparency and its contributions to stability is increased when OTHER states take parallel steps.”

That said, a State Department official added on background that the U.S. “continues to view transparency among nuclear weapon states as extremely valuable for purposes of building confidence, avoiding misperception, and encouraging dialogue that can help mitigate the risk of costly arms competitions.”

Transparency, in other words, can be diplomatically productive. Exposing Chinese officials to complex internal U.S. policy debates could help catalyze China’s internal discussions, says Tong Zhao, senior fellow with the Nuclear Policy Program at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

There are movements on this front. At a summit last November, U.S. and Chinese diplomats discussed whether states are at risk of ceding too much nuclear oversight to artificial intelligence systems. Though no agreements came of it, China’s willingness to discuss high-level principles of conduct could potentially be a productive wedge issue into other discussions, Dr. Zhao adds.

Russia for now appears to be stiff-arming the idea of nonproliferation talks with Washington, citing U.S. support for Ukraine, even as the sole remaining arms control agreement between the U.S. and Russia – the New START Treaty – will expire in February 2026.

The prospects for treaty renewal look remote for now, but surprising breakthroughs have emerged before. Even after President Reagan called the USSR an “evil empire,” for example, the two nations in 1985 agreed that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought,” notes Dan Smith, director of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Though straightforward, this sentence was considered a landmark declaration, and Russia, China, the U.S., France, and the United Kingdom reaffirmed it in 2022. Beyond being a hopeful signal, these sorts of statements “actually inform the thinking” of governments, Mr. Smith adds.

“Keep engagement alive”

At the same time, these governments are wrestling with the prospect of increasing U.S. isolationism, which many analysts point to as one of the most troubling deterrence trends.

The possibility of a Trump presidency, for example, is prompting European allies, who benefit from America’s nuclear umbrella, to question whether it will hold – or whether they should pursue their own nuclear programs.

It doesn’t help that Ukraine, which voluntarily gave up its nuclear weapons after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, is now bearing the brunt of as yet unsated Russian aggression.

Countering isolationist inclinations will mean renewed civic education, cultural dialogue of the sort that emerged in wake of the recent “Oppenheimer” film, and more, says William Hartung, senior research fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft.

In places like Kimball, there’s less opportunity for disengagement.

Student Jessica Terrill says she’s used to seeing missile silos, like one near her aunt’s house.

“That’s definitely kind of scary sometimes,” says the high school senior. “It’s like, oh man. If those go off, we’re going to know.”

Today’s news briefs

• Abortion ban repealed: Arizona’s Senate votes 16-14 to repeal the state’s 1864 ban on abortion, which could have taken effect within weeks. Two Republican senators crossed party lines to vote in favor of repeal.

• Biden on protests: Some 200 arrests overnight at UCLA bring the total across the United States to more than 2,000 at dozens of college campuses. President Joe Biden says that “order must prevail” but opposes sending in the National Guard.

• Harvey Weinstein trial: The former Hollywood producer will be retried in New York, the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office said May 1, a week after the state’s highest court threw out his 2020 rape conviction, hailed as a milestone for the #MeToo movement.

• Gun rule lawsuit: More than two dozen Republican state attorneys general sue the Biden administration to stop a new rule that would require gun dealers to obtain licenses and conduct background checks when selling firearms at gun shows and online.

• Solomon Islands election: Lawmakers elect former Foreign Minister Jeremiah Manele as prime minister in a development that suggests the South Pacific islands will maintain close ties with China.

Student protests dominate the news. For most young voters, a different issue is No. 1.

As student demonstrators clash with authorities on campuses nationwide, it’s raising questions about the youth vote in the fall. But polling shows most young people are far more focused on the economy than on the Mideast.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

As colleges and universities across the United States continue to grapple with student protests over Israel’s controversial military campaign in Gaza, it is sparking conversation about whether President Joe Biden will pay a price at the ballot box among young people, a key voting bloc for Democrats.

Certainly, some students might decide to stay home or cast a protest vote against Mr. Biden – and in a close election, even a small loss of support can hurt.

Yet for all the passions currently on display, polling suggests the Middle East is not the determining issue for most young people that headlines make it out to be. Indeed, when it comes to political priorities, the younger generation isn’t all that different from older ones: They’re mostly focused on the economy.

Nearly one-third of voters between the ages of 18 and 29 rank the economy as their primary concern, according to a Harvard Institute of Politics poll released last month. That’s compared with only 2% who rank the Israeli-Palestinian conflict first.

“The loudest voices aren’t usually representative of where the majority of folks are, even within one generation,” says Stefan Hankin, a Democratic pollster.

Student protests dominate the news. For most young voters, a different issue is No. 1.

When asked what issues are top of mind as they prepare to vote in their first presidential election this November, Cassidy Mazyck and Alexia McNamara, students at Virginia Commonwealth University, list several.

“Probably guns and women’s rights. Abortion is a huge one,” says Ms. Mazyck, who is studying clinical radiation science.

“I would say jobs or women’s rights,” says Ms. McNamara, an information systems major.

“Oh, and student loans for sure,” adds Ms. Mazyck.

Neither mentions the Middle East.

The omission seems striking – given that they are sitting on yellow Adirondack chairs less than 40 feet away from the university’s “liberation zone,” where a group of their peers is loudly pounding on bucket drums and chanting slogans like “Israel is a racist state!” and “Biden, Biden you will see, Palestine will be free!” Later that evening, the protest would turn violent, with police using tear gas to clear the encampment and protesters throwing objects at officers. Several arrests were made.

As colleges and universities across the United States continue to grapple with student protests over Israel’s controversial military campaign in Gaza, it is raising new questions about whether President Joe Biden will pay a price at the ballot box among young people, a key voting bloc for Democrats. In remarks from the White House Thursday morning, Mr. Biden said he supported peaceful protest but not violence, intimidation, or “chaos.” Asked if the demonstrations on campuses had caused him to reconsider U.S. policy in the region, he responded, “No.”

Certainly, some students upset about Israel and Gaza might decide to stay home or cast a protest vote against Mr. Biden – and in a close election, even a small loss of support can hurt.

Yet for all the passions currently on display, polling suggests the Middle East is not the determining issue for most young people that headlines make it out to be. Indeed, when it comes to political priorities, the younger generation isn’t all that different from older ones: They’re mostly focused on the economy.

Nearly one-third of voters between the ages of 18 and 29 rank the economy as their primary concern, according to a Harvard Institute of Politics poll released last month. That’s compared with only 2% who rank the Israeli-Palestinian conflict first. A majority of young voters also say they don’t follow national politics closely, and nearly three-quarters don’t consider themselves politically engaged or politically active.

“The loudest voices aren’t usually representative of where the majority of folks are, even within one generation,” says Stefan Hankin, a Democratic pollster. With Election Day still six months away, he adds, there’s plenty of time for any number of issues to rise to the surface or fall away. “What exactly is going to be driving people come November is a big question mark.”

Overall, Americans’ interest in the Middle East has actually been declining, according to data from Mr. Hankin’s Trendency Research. And no generation has seen a greater drop-off than Generation Z, 64% of whose members reported paying attention to the Israeli-Palestinian issue in October, but only 38% of whom were paying attention come March.

Among those who are closely following it, however, most have grown increasingly critical of Israel’s actions.

In the shadow of Virginia Commonwealth University’s library on Monday, about 50 young people, several wearing keffiyehs, march in a circle while a young woman leads call-and-response chants over a megaphone. Organizers pass out sunscreen and Gatorade beneath signs that read “Freedom by any means” and “From the river to the sea.” Like many protesters on other campuses across the country, these VCU students are demanding their school divest from companies with ties to Israel.

“There’s just so much funding for Israel, and that goes to the bomb strikes,” says Isabelle Cofield, a medical science student who has joined the demonstration and credits social media for “helping spread the issue” among her generation. When asked whom she plans to vote for in November, Ms. Cofield groans and says she’s unsure who will be the “lesser of two evils.”

This uncertainty was shared by many protesters and bystanders alike on VCU’s campus – regardless of their opinions on the situation in the Middle East. Almost a dozen students tell the Monitor they plan to vote in the presidential election this fall, but they’re not sure for whom.

Niya Shorts, for example, a criminal justice student who’s studying in the spring sunshine a few blocks from the protest, says she’s most concerned about affordable schooling, housing, and gun control. But she says she plans to “look again” at both Mr. Biden and former President Donald Trump before making a decision.

Many young people just aren’t focused on politics right now, says Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg, director of Tufts University’s CIRCLE, which studies youth civic engagement. “The peak of registration and mobilization for young people is much later, more towards the end of the summer.”

Still, some students say the situation in Gaza will absolutely influence their vote. Sareen Haddad, a Palestinian psychology student leading VCU’s protest, says that she and many of her peers plan either to not vote or to cast ballots for third-party candidates like the Green Party’s Jill Stein, who was arrested this week at a pro-Palestinian protest on the campus of Washington University in St. Louis.

“For anybody who currently is in a position of power that is not calling for an immediate cease-fire, supporting humanitarian aid into Gaza, and also defunding the Israeli military, the support from my generation, at least, plummets completely,” says Ms. Haddad. “I can tell you for sure that anybody who supports the Palestinian cause is not for Biden – and anybody who supports the Palestinian cause and has a heart is not for Trump, either.”

Patterns

Facing Russian threat and an uncertain America, Europe rearms

Washington has long urged European nations to spend more on their own defense. Russia’s Ukraine invasion, and European doubts about America’s role in tomorrow’s world, have had the desired effect.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Two words – stark and sober words – sum up a dramatic mood swing in Europe that could redefine, and ultimately loosen, the Continent’s decades-old alliance with the United States.

War footing.

That’s a phrase most recently voiced by British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, but he is only one of a growing number of European leaders who have concluded that the post-Cold War “peace dividend” is over, and that defense spending must increase.

That’s because of two increasingly unsettling security concerns, one to the east, the other to the west.

The more immediate threat is Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

But there is another, longer-range worry: that it might not be wise to rely too heavily on the U.S. to guarantee European security, whoever wins the forthcoming presidential election. The recent six-month holdup of U.S. military aid to Ukraine underlined that concern.

European nations, in response, are almost all spending more money on defense now, but putting the Continent on a real “war footing” would be an immensely costly and politically difficult challenge.

Money spent on weaponry is money not spent on domestic social programs. The old conundrum is rearing its head again: guns or butter?

Facing Russian threat and an uncertain America, Europe rearms

Two words – stark, sober words – sum up a dramatic mood swing in Europe that could redefine, and ultimately loosen, the Continent’s decades-old alliance with the United States.

War footing.

That phrase, voiced most recently by British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak in a speech last week, is especially significant because it is such a jarring departure from Europe’s long-settled economic credo.

For years, the refrain heard in European capitals has been the post-Cold War “peace dividend” – the leeway governments found they had to slash defense spending and invest more money in domestic economic and social priorities instead.

Today, Mr. Sunak is only one of a growing number of European leaders to have concluded that the days of the “peace dividend” are over, and that Europe needs to spend more – much more – on its defense.

And while they’re aware of how politically and practically daunting that goal is, they clearly feel a growing sense of urgency.

That’s because of two increasingly unsettling security concerns, one to the east, the other to the west.

The more immediate threat is Russia’s full-scale war of subjugation against Ukraine.

But there is another, longer-range worry: that, whoever wins this November’s U.S. presidential election, Europe cannot necessarily keep relying on America to be the superpower guarantor of the Continent’s security.

Both these fears have sharpened in recent weeks.

In Ukraine, Russian forces have been intensifying their attacks and begun making advances.

And in Washington, even as the Ukrainians found themselves running short of artillery shells, it took months for the Biden administration to overcome opposition from House Republicans and secure some $60 billion in desperately needed military aid for Kyiv.

European countries did try to fill the gap.

Indeed, in a letter to European Union leaders ahead of a summit six weeks ago, it was the president of the bloc’s ministerial council, Charles Michel, who first raised the call for “a paradigm shift” in Europe’s defense thinking.

“It is high time that we take radical and concrete steps,” he told them, “to be defense-ready, and put the EU’s economy on a war footing.”

The EU went on to approve more than $5 billion of additional military aid to Ukraine, and began trying to buy up all available artillery shells from other countries. But European leaders know that they simply do not have a big enough defense industry, nor large enough arms stockpiles, to come anywhere near taking over Washington’s critical role.

A more profound shift in economic priorities is clearly going to be necessary for that to become possible, especially among Europe’s main economic and military powers.

That is one reason Mr. Sunak’s comments were especially significant.

Countries on Europe’s eastern fringe, closest to Russia – such as Poland, Finland, and the Baltic states – have never needed convincing of the need to ratchet up defense investment.

Yet that message has taken considerably longer to resonate in countries further west, especially in Europe’s leading economic powerhouse, Germany, and in its main military powers, Britain and France.

Mr. Sunak, speaking in Poland with the secretary-general of the NATO alliance also in attendance, announced plans to increase Britain’s defense spending to 2.5% of gross domestic product – above the decade-old NATO target of 2%.

He urged Europe’s other NATO members to make that their new minimum, too.

Three days later, French President Emmanuel Macron also weighed in on the need for Europe to revitalize its defense industries. Emphasizing the importance of preventing Russia from prevailing in Ukraine, he said the EU should deploy its shared economic resources to ramp up arms production.

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, in a social media post, responded: “France and Germany want Europe to be strong. Your speech contains good ideas on how we can achieve this.”

Still, while most European countries have begun spending more money on defense since the start of the Ukraine war, putting the Continent on a real “war footing” would be a huge and difficult undertaking.

One obvious challenge is the old economics textbook choice: guns or butter?

Europe’s economies are still stuttering from multiple jolts: the 2008 world financial crisis, the pandemic, and the Russia-Ukraine war. More funds for defense would inevitably mean fewer funds for already cash-strained domestic priorities.

The scale of spending needed is enormous. Most of NATO’s European members have met, or are getting close to meeting, the old 2% target. But, beyond the eastern countries nearest to Russia, very few are within reach of Mr. Sunak’s proposed higher benchmark.

His hope, Mr. Macron’s hope, and that of a growing number of other European leaders, is that voters will quickly learn the lessons of years of underinvestment in defense.

And that’s a message that would resonate with one of Mr. Sunak’s predecessors, the prime minister who first coined the idea of a “peace dividend,” along with then-U.S. President George H.W. Bush.

Speaking in 1991, shortly after losing office, Margaret Thatcher told a luncheon honoring her in Washington, “The only real peace dividend is, quite simply, peace.”

And how had her generation come to enjoy it? “Because of the investment of billions of dollars and pounds in defense.”

Flight delayed? Air traffic control woes go beyond what FAA bill would fix.

Flying has become frustrating for many Americans. Here we explain one systemic issue behind delays and threats to safety – and the steps Congress can take to speed progress.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Sophie Hills Staff writer

Understaffing in air traffic control has been a challenge ever since President Ronald Reagan fired most of the United States’ controllers during a 1981 strike. Today the control towers are also handling more planes, drones, and rocket launches without the best technology. Most U.S. airports still track flights with paper strips, and overstretched controllers sometimes have to extend time between landings, creating delays.

Missed budget deadlines have also made it tough for the Federal Aviation Administration to plan ahead. Lawmakers have yet to pass a reauthorization bill that spells out funding priorities for fiscal years 2024-28, which was due Oct. 1, 2023. They now have until May 10 to pass the bipartisan measure, which includes increased investment in air traffic control personnel and technology.

“Reauthorization is extremely important in providing a level of stability,” says Michael Huerta, former head of the FAA and chair of a safety review team convened after a series of near misses last year. “But more needs to be done.”

President Joe Biden’s 2025 proposed budget increases the FAA’s funding by 10% and includes $43 million for controller hiring and training. But first, Congress has to pass the 2024 FAA reauthorization – more than seven months late.

Flight delayed? Air traffic control woes go beyond what FAA bill would fix.

The 2.9 million airline passengers who take to the American skies every day are increasingly grumpy as they face delays, cancellations, and ever-higher fees for things that were once free. The reasons are complex, but when it comes to delays, a key issue is the growing strain on the air traffic control system responsible for preventing collisions among 45,000 daily flights.

Since President Ronald Reagan fired most of the controllers in the United States during a 1981 strike, understaffing has been a challenge. Today controllers are also handling a more complex airspace, including more drones and rocket launches. And they’re doing it without top technology. All but seven U.S. airports, for example, track flights with paper strips rather than with an electronic system – a system Canada has used for more than two decades.

A series of near misses last year – including a FedEx plane nearly landing on top of a Southwest plane taking off in Austin, Texas, after both were cleared by the same controller – has prompted a deeper look. A federal safety review team devoted more than a third of its November report to bolstering the strained air traffic control system.

Officials insist that the skies are still safe overall. But maintaining safety can come at customers’ expense. For example, overburdened controllers may spread out planes further and extend the time between each landing on a given runway, resulting in delays.

The staffing and technology constraints are partly Congress’ fault. Missed budget deadlines and government shutdowns have made it tough for the Federal Aviation Administration to plan ahead. Now there’s a once-in-five-years opportunity to address air traffic control issues as Congress reviews FAA spending priorities for 2024-28.

The House and Senate committees that oversee the agency both approved bipartisan FAA reauthorization bills that include measures to address the air traffic control shortages and technological hurdles. But neither fully addresses the chronic underfunding and its effects. After missing an Oct. 1, 2023, deadline, Congress must vote on both bills before the current temporary funding expires on May 10.

“Reauthorization is extremely important in providing a level of stability, so that’s a good thing,” says Michael Huerta, the former administrator of the FAA and chair of the safety review team behind last November’s report. “But more needs to be done, and we’re really encouraging the administration and the Congress to look more broadly at what the long-term needs of the agency are and how best to address them.”

Struggle to recruit, retain controllers

When Jeffrey Thompson was 18 years old, an Air Force recruiter lent him a DVD of “Pushing Tin,” starring John Cusack as an air traffic controller, and convinced Mr. Thompson to be one himself.

“ATC saved my life,” says Mr. Thompson. “It helped me create a life and destroy generational curses.”

After years with the military overseas, he was hired as an air traffic controller at Dallas Fort Worth International Airport just as all the controllers brought on after the Reagan-era purge were retiring.

“People weren’t certifying in air traffic control fast enough,” he says, adding that the FAA fast-tracked people who weren’t necessarily ready. He also saw inexperienced controllers not getting critical mentoring.

Confronted by such understaffing and a “good old boy” culture that didn’t feel welcoming to him as a Black man, Mr. Thompson left to pursue a different career in 2018.

The November report called for a review of the culture and training atmosphere at the FAA Academy in Oklahoma to determine whether they were deterring candidates who could succeed.

The FAA also faces a class action lawsuit alleging that during the Obama administration it sidelined more than 2,000 qualified applicants, who had already passed an assessment test, in an overhaul of the hiring process designed to increase racial diversity among air traffic controllers.

This year the agency plans to hire 1,800 controllers – 300 more than last year – and is filling every seat at the academy. It began allowing qualified graduates from collegiate air traffic control programs to skip the academy and go straight to a facility. It is also accelerating hiring of military controllers, and using modernized simulators to train new hires more efficiently.

But only about 70% of candidates pass the academy certification tests. And many people are leaving the field. According to the safety review report, the FAA hiring plan will yield a net increase of fewer than 200 controllers by 2032.

The Department of Transportation’s inspector general found last summer that 3 in 4 critical airports are understaffed. At the bottom of the list was a New York facility (N90) that is staffed at only 54% and has only eight operational supervisors out of the 30 authorized.

Three-quarters of all delays in the U.S. occur because of delays around New York City, a particularly complex and congested airspace, according to the FAA. In the summer of 2022, Reuters reported, more than 40,000 flights were delayed due at least in part to air traffic control understaffing. As a result of such understaffing, last year airlines reduced by 10% the number of flights they were offering into New York – a cut that is still in effect.

Fewer controllers means more flights each controller has to track when others are on the required breaks. It also means more overtime shifts. While the additional pay is attractive, it can lead to mistakes – and burnout. “They’re wearing the controllers out,” says a recently retired controller and local union representative. “When you keep running the system at a bare minimum, something’s going to break.”

Overworking controllers can increase the stress of an already intensely stressful job. And the controllers are acutely aware of the high stakes. “You can’t make mistakes,” says the retired controller.

Serious runway incursions or near misses remain rare. In the past fiscal year, there were only 23 out of 54.4 million flights, and only about a fifth of those were due to controllers’ actions or inaction. However, that marked a 44% increase over the previous year.

Aging technology

One way to minimize safety issues is improved technology that alerts controllers and gives them more situational awareness. But there’s a long way to go.

The switch from paper flight-tracking strips to electronic ones at 49 U.S. airports is scheduled to take another five years. A hazard-alert system known as NOTAM (Notice to Airmen) failed last year, causing the first nationwide shutdown of U.S. airspace since 9/11. And most instrument landing systems, which guide airplanes on their final approach to the runway, are more than 25 years old. Air traffic control towers are 40 years old on average.

“It’s not functioning the way a major utility ought to function,” says Robert Poole, director of transportation policy at Reason Foundation, a libertarian think tank, noting that other countries are far ahead of the U.S.

The Senate’s new FAA reauthorization bill proposes $18 billion to upgrade NOTAM and expand technology aimed at preventing runway collisions from 43 airports to all large and midsize airports. Another improvement under way is transitioning from radar to GPS so that air traffic controllers have a more precise picture of a plane’s whereabouts.

“It’s like going from an impressionist painting to HDTV,” says Mr. Huerta, the former FAA head.

Such technological investments have been hampered partly by the expense of maintaining legacy systems, many of which are too old for manufacturer support and replacement parts. That’s partly because the five-year funding cycle limits long-term planning and investments.

“There is quite a lot of pressure on the FAA to do its mission with years of not funding it the proper way,” says Patricia Gilbert, a veteran air traffic controller who was the executive vice president of the National Air Traffic Controllers Association from 2009 to 2021 and a co-author of the November 2023 safety review report.

“And it’s not all Congress,” she adds, noting that administrations have limited needed investments at FAA in favor of other funding priorities.

President Joe Biden’s 2025 proposed budget increases the FAA’s funding by 10% and includes $43 million for controller hiring and training. But first, Congress has to pass the 2024 FAA reauthorization – more than seven months late.

Points of Progress

Stories of resilience: Bees make a comeback, and immigrants help economies

In our progress roundup, new data shows workers undergirding vital systems: In Latin America, Venezuelans who’ve fled their own country boost the gross domestic product in their adopted homes. And in the United States, bees colonies have grown.

Stories of resilience: Bees make a comeback, and immigrants help economies

Domesticated honeybee populations are at an all-time high

Since 2006, steep winter losses of worker bees have spurred scientists and the U.S. government to try to understand colony collapse disorder. Honeybees pollinate four-fifths of all flowering plants, which makes one-third of the food system dependent on bees.

But new data from the Census of Agriculture shows that honeybee colonies have increased by 1 million in the last five years, for a total of 3.8 million.

Because the tally includes colonies on any plot of land that makes over $1,000 a year from agricultural products, higher honey prices may have pushed some hobbyists’ bees into the count. Part of the increase is also attributed to tax breaks for bee colonies on farms in Texas, which now has the highest number of operations in the U.S.

Experts emphasize that feral bees and other wild pollinators still need more support, such as reduced pesticide use and more flower-rich habitats.

Source: The Washington Post

Venezuelans are boosting economies where they’ve immigrated

Since Venezuela’s economy collapsed in 2014, nearly 8 million people have fled poverty and turmoil, seeking refuge across Latin America. Two studies from institutions including the World Bank and the United Nations refugee agency found that the new workforce, which includes displaced people from countries in addition to Venezuela, would boost gross domestic product in host nations by 0.10% to 0.25% on average each year from 2017 until 2030.

Over time, economic growth from migrants’ contributions outstrips state spending on public services provided to newcomers, the studies found. Immigrants fill labor shortages for less-desirable jobs, and their spending can drive demand for goods and services.

Xenophobia and a lack of recognition of Venezuelans’ credentials have led to underemployment of professionals, and many lack access to social services such as health insurance. The studies argue that countries could further improve productivity by better integrating new arrivals.

Sources: The Guardian, The Conversation

Chemists in Switzerland created a sustainable plastic from agricultural waste

Plastic production is responsible for 3.4% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and because plastic never biodegrades, it is a major source of environmental pollution. A team at Switzerland’s federal technology institute used a sugar structure commonly found in biomass to produce a class of strong plastics with little waste.

The team’s catalyst-free process uses dimethyl glyoxylate xylose, a carbohydrate created from agriculture leftovers such as wood and corncobs, to create polyamides – a class of plastics that includes nylon and is known for durability and strength. The new plastic maintained integrity through several mechanical recycling cycles, meaning it can be used multiple times.

The new plastic could be used to create everything from car parts to consumer goods. The team’s analysis suggests that the material is competitive with traditional polyamides. In 2019, the university spun off a startup that will be able to scale up production of the new material.

Sources: Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne, Nature Sustainability

Traditional practices are keeping agriculture sustainable in Oman, a country of mostly deserts

In the Hajar Mountains, thousands of years of skillful water and soil management have allowed people to grow a wide variety of foods, from date palms to carrots.

Through an ancient system of irrigation known as aflaj, water is channeled from mountain springs and pools to terraced fields. For hundreds of years, farmers have mixed river sediment with manure from goats raised on the land to create the terrace soil.

Though climate change and shifting socioeconomic forces in the developed country threaten Oman’s oasis agriculture, new crops such as olives are taking off, and crop diversity remains high. Andreas Bürkert, a professor of agroecosystems, warns of the need to maintain traditional knowledge but sees the local ways as “a model for sustainability. ... It’s the only place in the world I know of where 1,500 years of irrigated agriculture ... has not led to salinization,”

he said.

Source: Mongabay

A Nigerian radio show mediates grievances for citizens with little power and delivers a sense of justice

In Sokoto state, nearly 90% of the population lives below the poverty line, and three-quarters are unable to read or write English – Nigeria’s official language. That can make navigating the legal system difficult. “Kukana,” a weekly show airing on Sokoto’s Vision FM, researches complaints and often puts the aggrieved party on the air with a lawyer.

Hosts say “Kukana,” whose name roughly translates to “my woes,” attracts more than 1.7 million listeners. One week, members of Sokoto’s Joint Disabled Association discussed the sudden cessation of their government benefits. The governor visited the coalition after hearing the show, and the stipends soon restarted.

In the capital, Abuja, a similar program, “Brekete Family,” invites people to share their problems on television and radio, and provides connections to relevant authorities.

Source: Reasons to be Cheerful

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

European shield in Georgia

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Since it invaded Ukraine, Russia has become more open about its goal to piece back together the states of the fallen Soviet empire. Reactions to this Humpty Dumpty project have brought arms to Ukraine and sanctions on Russia’s economy. It has also brought an offer of protection to several former Soviet states – a chance to join the European Union and enjoy the shield of a community abiding by democratic values.

On Wednesday, one such former Soviet state, Georgia, saw the largest street protests yet against a bill that, if passed by the ruling party, could derail EU membership. The bill has vague provisions that would curtail the work of civil society and news outlets if such groups receive more than 20% of their funding from abroad.

It is unclear if Russia is behind the bill. But what is clear is that the ruling Georgian Dream party is worried about losing power in elections this October if journalists and civic activists keep exposing government corruption, interference in the courts, and other erosions of the rule of law.

Polls show that some 80% of Georgians support EU membership. Aligning the country with European values is widely seen as a safeguard against Russia.

European shield in Georgia

Since it invaded Ukraine more than two years ago, Russia has become more open about its goal to piece back together the states of the fallen Soviet empire. Reactions to this Humpty Dumpty project have brought arms to Ukraine and sanctions on Russia’s economy. It has also brought an offer of protection to several former Soviet states – a chance to join the European Union and enjoy the shield of a community abiding by democratic values.

On Wednesday, one such former Soviet state, Georgia, saw the largest street protests yet against a legislative bill that, if passed by the ruling party, could derail EU membership. The bill has vague provisions that would curtail the work of civil society and news outlets if such groups receive more than 20% of their funding from abroad.

A similar measure in Russia has been used since 2012 to silence political opposition. The former Soviet state Kyrgyzstan has followed Moscow’s example while Kazakhstan is weighing it. A similar measure in Hungary, an EU member, was nullified by the European Court of Justice.

It is unclear if Russia is behind the Georgia bill. But the de facto leader of the ruling Georgian Dream party, Bidzina Ivanishvili, is a billionaire who made his fortune in Russia. What is clear is that his party is worried about losing power in elections this October if journalists and civic activists keep exposing government corruption, interference in the courts, and other erosions of the rule of law.

This week’s harsh crackdown on protesters – whose numbers reached more than 100,000 – hints at the party’s attempt to hold on to power or, at the least, create social polarization. On Tuesday, President Salome Zourabichvili, whose post is largely ceremonial, said the police crackdown was “totally unwarranted, unprovoked and out of proportion.” She is a former member of Georgian Dream who left as the party drifted toward authoritarian ways.

Polls show that some 80% of Georgians support EU membership and the reforms required to achieve it. Aligning the country with European values is widely seen as a safeguard against Russia. The war in Ukraine is not the only front to uphold national sovereignty and personal liberties.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Prayers for those in a war zone

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Karen Gould

Wherever in the world we are, praying from the basis of God’s love and care for all is a powerful way to support our brothers and sisters around the globe.

Prayers for those in a war zone

For some time now I have been teaching English at the local Ukraine Association in my country. The students are mostly women – mothers – whose husbands are fighting on the front line. Some of these women have become close friends.

A while ago, one of these friends, who knows I am a Christian Scientist, asked me to pray for her and her daughter as they undertook a hazardous trip back to Ukraine to visit their family, having not seen them for over a year. I assured her that I would.

Initially I didn’t know where to begin. How do you pray for someone entering a war zone?

What came to me was to pray to know more clearly the omnipresence of God as Love. So that’s what I did throughout their trip. I prayed from the standpoint of the supremacy of God, who is entirely good.

There’s a Bible verse that includes this promise from God: “I have loved thee with an everlasting love” (Jeremiah 31:3). This is a promise for everyone. As God’s children, we’re not mortals subject to danger but spiritual ideas – held safe in the uninvaded, and uninvadable, kingdom of heaven. We can never be separated from God, divine Love, or outside of God’s presence. Everyone has an innate ability, as God’s beloved child, to know and feel that spiritual reality.

My friend later reported that despite the ongoing threat and the constant sirens and drones overhead, she felt safe during her visit and didn’t feel any of the trauma she had previously. Instead she was able to focus on the joy of being with her family and the beauty around her, which the power of divine Truth and the understanding of God’s presence with her enabled my friend to see.

I thought of this experience when I was listening to an Oct. 2023 BBC interview with two women – both mothers, one in Gaza and one in Israel, both caught in the Israel-Hamas war. They were asked what they would say to a mother on the “other side.” Their responses reflected a shared love for one another and for their children. The mother in Israel said, in effect, “That my heart goes to her and her children. I’m sure that as a mother she would pray for peace as I do.” The mother in the heart of the Gaza Strip replied along the lines of, “I share with you the same fears. I share with you the same concerns for the future of my children.”

I found the interview so moving that in tears I reached out to God in prayer. What would I say to them, if I could? What would I want them to know?

Through Christian Science I have come to know God as Father-Mother, ever-present Love, tenderly caring for all of us – His, Her, beloved children. And as Christ Jesus proved through his healing ministry, holding to this spiritual reality enables us to experience more of God’s harmony in day-to-day life.

So my prayers affirmed that those dear mothers – indeed all mothers, fathers, children, and wider families – are in the presence of divine Love and can feel and know this Love. The mothering, guiding, protecting love of God surrounds everyone, no matter which side of a border they may be on.

The woman who discovered Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy – also a mother – wrote a poem that beautifully speaks to the fathering, mothering love of God. One of the verses says:

Beneath the shadow of His mighty wing;

In that sweet secret of the narrow way,

Seeking and finding, with the angels sing:

“Lo, I am with you alway,” – watch and pray.

(“Poems,” p. 4)

Most of us can’t claim to know what it’s like to be in a war zone, but we can embrace in our prayers those who are – whether in Ukraine, Israel, Gaza, or elsewhere. We can hold steadfastly to the spiritual facts that all of God’s children are held safe in divine Love, and that everyone, everywhere, can know God’s mothering love as a tender yet powerful comforting, healing, and saving presence.

Viewfinder

May showers

A look ahead

We have a bonus read for you today: Sen. Steve Daines of Montana, who chairs the National Republican Senatorial Committee, joins The Monitor Breakfast to talk about his party’s plans for the fall Senate elections.

And come back tomorrow. Our stories include a look at how colleges are responding to protesters who are angered by Israel’s continued military action and demanding divestment.