- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Why Dallas wants police to leave a ‘light footprint’ while fighting crime

- Today’s news briefs

- In US, grim headlines for electric vehicles don’t tell the whole story

- How China’s electric vehicles are dominating the industry

- NBA playoffs without Curry? James? Durant? A new guard rises in basketball.

- Housing projects: Paris curates its streets, and Navajo homes get addresses

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Kindness and decency are still out there, and still powerful

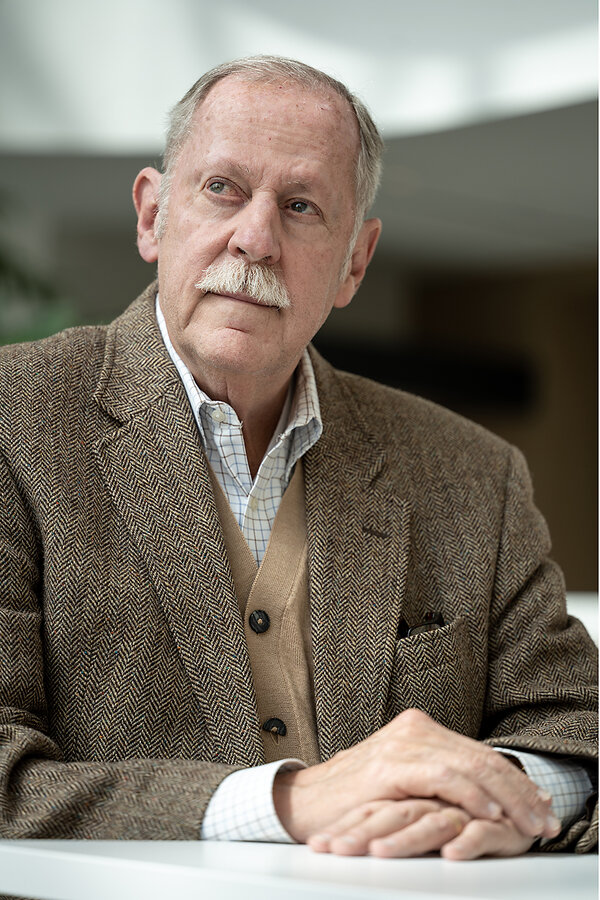

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Remember kindness? Remember decency? Remember generosity? Well, guess what. They’re still happening. Here’s the proof.

Maybe we can change things for the better, after all. Maybe it happens slowly. Maybe it’s one person at a time. But maybe that’s just how revolutions start.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Why Dallas wants police to leave a ‘light footprint’ while fighting crime

Who is responsible for the safety of a community? Police are an obvious answer. But in Dallas, efforts to address violent crime go beyond the usual suspects.

-

Riley Robinson Staff photographer

When Maj. Jason Scoggins first heard about the new “light-footprint” strategies for the Dallas Police Department, he was skeptical.

“You turn on your cruise lights and you’re there for 15 minutes, and that’s supposed to deter crime?” Major Scoggins recalls thinking.

He’s a second-generation Dallas police officer, and he and his father represent a combined half-century of policing experience. But this strategy “was not something that I’ve ever seen,” he says.

The practice hinges on the idea that police presence alone can deter violent crime when “hot spots” are at their hottest. So officers are instructed to simply make themselves visible.

“If this ... reduces violent crime,” Major Scoggins says, “sign me up. I’m all for it.”

But law enforcement is just one part of a new multipronged approach to fighting violent crime. The city is also tapping the expertise of community organizations and local leaders to interrupt violence and to help coax offenders to enroll in programs to stabilize their lives.

“What’s important is what it’s not,” says Michael Smith, a criminologist at the University of Texas at San Antonio. “This isn’t police officers getting out of their cars, stopping everything that moves. It’s a modern, 21st-century, light-footprint crime reduction strategy.”

Why Dallas wants police to leave a ‘light footprint’ while fighting crime

On a frigid late-February afternoon this year, fighting violent crime has brought Victor Alvelais to a fast-food drive-thru here in the southern part of Dallas.

After his chicken tenders finally arrive, he drives a few minutes down the road to the scene of a recent crime. A few weeks earlier, a gunman shot through a fence and wounded five children at an apartment complex in South Dallas.

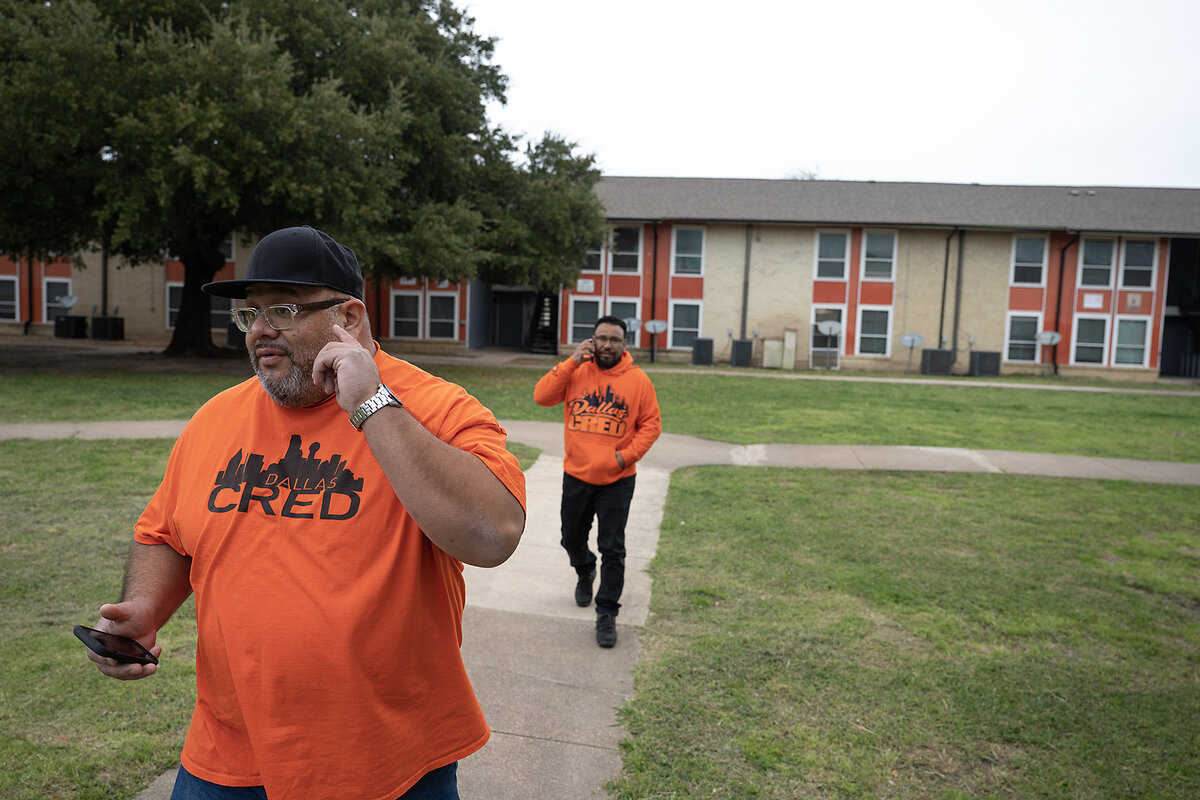

Within two days of that shooting, Mr. Alvelais was there. The director of Dallas Cred, a local violence intervention group, he’d already been meeting with two teenage brothers who live there, talking them out of picking up their own weapons and getting revenge.

On this afternoon, he’s still responding. He’s with three other members of Dallas Cred this time, each of whom are wearing the organization’s bright-orange T-shirts, as well as a reporter he agreed could tag along.

They coax the brothers onto a porch outside their ground-floor apartment. It’s cold, so they’ve draped themselves in thick blankets. Juan Javier Pérez, a member of the team, throws some friendly shade, calling them “soft” for shivering under blankets while he’s wearing shorts. (Mr. Pérez is from the colder climes of Michigan.)

The conversation turns serious. They admonish the younger brother for picking up an assault charge. They ask him to let them know when he has a court date so they can talk to the judge.

It’s too cold for a longer conversation, and they shuffle back inside. But Mr. Alvelais says this was a productive meeting. The brothers still seem receptive to their emphasis on nonviolence. They listen to him. Perhaps they even trust his “cred,” or credibility, since he served nearly 30 years in prison for a homicide.

Just as he begins to drive away, the older brother runs out and stops him. Walking over to the driver’s window, he quietly tells Mr. Alvelais his family could use some food. So he heads to the fast-food drive-thru, orders more chicken tenders, and brings them back to the brothers.

“It’s a little thing,” Mr. Alvelais says. “A hot meal on a cold day, it goes a long way.”

Since 2021, Dallas has been taking approaches like violence intervention to make the city’s wider efforts to fight violent crime more effective. Relying on “trusted messengers,” violence intervention programs seek to build community relationships that address violent crime before it happens. Cities such as Philadelphia, Baltimore, Chicago, and others across the United States have included such programs in their law enforcement budgets, with each asking, can law enforcement evolve to be more of a community effort?

Those at Dallas Cred believe it must. “[The police’s] responsibility is to react to a crime, arrest the perpetrator, and leave,” says Mr. Alvelais. “They can’t be in the midst of the communities trying to eradicate this way of thinking, or prevent any sort of retaliation once it happens.”

“Violence is an effect; it’s not the cause” of crime, says Untruan Grant, another member of the group today. “Really, nobody wants to be in trouble, but sometimes we feel like that’s the only resort. We’re giving them other resorts to be able to take, and that’s by counting on us.”

A new approach

In Dallas and other cities in Texas, however, efforts to include the wider community in addressing violent crime are just one part of a major rethinking about law enforcement. Criminologists and policymakers in the Lone Star State have been in the process of initiating new multiyear and multipronged approaches to law enforcement, drawing on 50 years of research into the nation’s evolving policing techniques.

Their new approaches have included embracing what have often been the controversial ideas of “hot spots policing.” In a technique pioneered in Minneapolis and exemplified by New York City’s CompStat program in the 1990s, police first meticulously map crime patterns throughout the city and then focus their resources on areas in which violent crimes occur most often.

They’ve also begun to include another technique pioneered in New York: “broken windows policing.” Also a decades-old strategy, this kind of policing includes removing signs of disorder and blight as officers aggressively target minor crimes like vandalism and loitering. According to the theory, a focus on smaller problems helps prevent more serious violence and mayhem.

Both techniques have been vigorously contested by critics who point out that this kind of policing often floods Black and Latino neighborhoods with police, placing them under much more intense scrutiny and causing conflict and inequities.

But in Dallas and other cities in Texas, officials say they are trying to avoid the mistakes of the past. “It won’t necessarily be all police,” says Robert Blanton, an assistant chief with the San Antonio Police Department. “It’s much more comprehensive than the hot spots [idea]. ... These are going to be much more thoughtful, or active, issues.”

Focused deterrence

This more comprehensive approach to public safety also includes an idea known as “focused deterrence,” which was pioneered in Boston in the 1990s. Focusing on a small number of “key” violent offenders, an array of law enforcement officials and community leaders brings such offenders into a room and, together, works to convince them to turn their lives around. Police, prosecutors, community members, crime victims, nonprofit groups, and former criminals marshal their efforts to address the roots rather than the effects of violent crime.

If they cooperate, the community members and nonprofit groups are here to help them. Former criminals are there to tell them it’s possible. But if they continue to reoffend, police and prosecutors tell them they will be sent to prison for as long as possible.

These varied strategies have never been implemented together as part of a long-term coordinated plan, says Michael Smith, a criminologist at the University of Texas at San Antonio, who helped design the multipronged plan for Texas jurisdictions. These strategies, though controversial, have been adapted in light of the negative effects they’ve had, he says.

“What’s important is what it’s not,” Dr. Smith says about Texas’ new approaches. “This isn’t police officers getting out of their cars, stopping everything that moves. It’s a modern, 21st-century, light-footprint crime reduction strategy.”

From skepticism to hope

When Maj. Jason Scoggins first heard about the new light-footprint strategies for the Dallas Police Department, he was skeptical.

Stocky, with a shaved head and a Texas drawl, Major Scoggins is a second-generation Dallas police officer. He and his father represent a combined half-century of policing experience, but this particular hot spots strategy “was not something that I’ve ever seen,” he says.

Using data analysis to identify a small number of high-crime locations – often as small as a street corner or apartment building – supervisors tell officers not to make any arrests or do any kind of enforcement, really. Their presence alone, according to criminologists, should deter violent crime when these hot spots are at their hottest. They are instructed to simply announce their presence.

“At first it sounded funny,” Major Scoggins says. “You turn on your cruise lights and you’re there for 15 minutes, and that’s supposed to deter crime?” Still, he was willing to give it a shot. “If this is [that] simple ... and it deters crime and reduces violent crime? Sign me up. I’m all for it.”

After the program launched in 2021, violent crime dropped 53% in the hot spots and 14% citywide in the first six months, the department reported. San Antonio, which started the plan last year, reported a 44% drop in violent crime in hot spots.

Melissa Cabello Havrda, a member of the San Antonio City Council and chair of its Public Safety Committee, was skeptical of the crime plan at first. “But I was hopeful, and it turns out I had a reason to be hopeful,” she says.

Residents of Edgewood, a neighborhood in her district on the city’s west side, were also skeptical. The area has one of the highest crime rates in the city, and last year its school district recorded more violent student offenses than any other. But as the residents have been seeing more police patrols in the past year, now they’re telling her they feel safer, she says.

“That’s a big win in my book,” says Councilor Cabello Havrda. “Hot spots isn’t meant to be a solution on its own, and I think they understand that.”

The hope is that this first, entirely police-driven phase of the multipronged plan can lay the groundwork for the later and longer-term techniques to succeed.

“This strategy builds over time,” says Thomas Abt, a professor of criminology at the University of Maryland. “It starts with very simple interventions ... and then it adds increasingly complex interventions on top. That’s very exciting, and I think it’s very smart,” he says. “You need a balanced set of enforcement and nonenforcement strategies. It’s very important to recognize that police are not the only people responsible for maintaining public safety.”

Dallas’s approach to “broken windows”

Like many in Dallas now, Kevin Oden doesn’t fit the traditional crime-fighting profile. But after cutting his teeth overseeing Super Bowls, natural disasters, and disease outbreaks, he’s at the forefront of Dallas’ efforts to make public safety a citywide responsibility.

Head of the city’s Office of Integrated Public Safety Solutions, Mr. Oden is responsible for how Dallas implements its version of the broken windows theory. In the past, the strategy called for police to crack down on minor offenses as a way to disrupt and deter more serious offenses. Inspired by research in Philadelphia, Mr. Oden believes environmental improvements in an area can also decrease violent crime.

So his agency has trained teams of code inspectors to join the efforts to help prevent violent crime. They fix gates and fences, improve public lighting, and relandscape crime-prone areas like the back corners of apartment complexes. They clean vacant lots, remove abandoned vehicles, and install security cameras outside businesses. They also make sure vacant buildings are inaccessible – and without broken windows.

Mr. Oden’s office also works with Dallas Fire-Rescue, Park and Recreation, and even Water Utilities to bring resources and security to high-crime areas. His office also hires violence interrupter programs like Dallas Cred, investing about $1 million a year in the work.

“By doing those things ... you really turn around the narrative of risk in an area,” Mr. Oden says. “And you do it without having to do additional policing or tie up resources.”

But there is a limit to how much police and civilian agencies like his can do to tackle violence.

“Ultimately, all of these areas share the same common need, and it’s investment in housing, investment in economic opportunity, income growth,” he says. “The long-term [solution] is to make the investments the way that they probably should have been done a long, long time ago.”

He also helps coordinate the city’s new focused-deterrence efforts, hiring agencies like the South Dallas Employment Project.

Its managing partner, Wes Jurey, is another unlikely crime fighter. Gray-haired and mustachioed, he looks more like a university professor than like a man who picks up the phone at 3 a.m. to make sure you get a bed at a homeless shelter. But he’s been working to help the dozens of participants in Dallas’ focused-deterrence program, as well as their families.

Fifty-one people have joined the program, which was launched in June last year. Coordinating with other nonprofits and government agencies, Mr. Jurey has helped at least 31 clients connect to a total of 166 services. So far, only one participant has been rearrested, but not for a firearm-related or violent offense.

Many of them “got in trouble because of other circumstances that are a little bit beyond their control,” Mr. Jurey says. “It’s difficult to challenge that. And yet they’ve committed a crime, and they’re going to have to take the consequences of that. We want to help them not commit another crime,” he adds. “But you have to get down to, what are the underlying causes? ... It takes it all. It’s not just the job. It’s not just finding a place to sleep.”

From menace to mentor

Antong Lucky knows a lot about those underlying causes.

He’d never worked with law enforcement until last summer, when he agreed to share his story with participants in Dallas’ focused-deterrence program. It’s exciting for him, he says, because the program is a microcosm of what he thinks public safety should be. He calls it “a NATO,” a citywide alliance committed to reducing violent crime.

His father went to prison when he was 9 months old, and his mother worked long hours to provide for them, even as drug dealers worked outside his front porch and bullies and gang members shadowed him around his South Dallas neighborhood.

In school he had been an honor roll student. But outside school he quickly learned that he had to be something else. By the time he reached high school, he was a leader in a notorious gang, the Bloods.

“As a kid, the law of self-preservation kicks in, so you start putting on what you think you’re supposed to be,” Mr. Lucky says. “Then next thing you know, you’ve created a gang. Next thing you know, you’re into drugs. Next thing you know, you’re standing in front of judge who’s saying you’re a menace to society,” he says.

“That speaks to a lot of kids across the country in urban communities,” he continues. “It’s easy to say these kids [are] just dangerous from the start, and they’re bad and they’re killers. But it don’t happen like that,” he adds. “No one wakes up and says, ‘This is what I want to be.’ Sometimes your circumstances can be strong to convince you to front like you’re that, to pretend like you’re that. And if you pretend long enough, you just end up being it.”

After a long prison sentence, Mr. Lucky committed to turning his life around. That involved negotiating a truce between the Bloods and the Crips, a rival gang, in 2000. And for decades, he’s worked to keep the peace in Dallas’ high-crime communities. Then the city hired him to help with focused deterrence.

Since Dallas implemented this plan, three other cities have followed suit. The results so far have been encouraging, albeit mixed. Dallas saw an increase in homicides last year compared with 2022, but most other kinds of violent crime have decreased since 2021.

Mr. Lucky, for his part, is optimistic. When he was growing up, “these types of efforts didn’t [exist]. They judged us before even trying to help us,” he says. “We’re not there yet. I think we’re getting there. We need an alliance of all types of people to help.”

In many ways, however, these ideas are still experiments. In 2021, the city hired Dallas Cred, which is supported by the national nonprofit Youth Advocate Programs Inc., but that contract expired at the end of 2023. The staff of the violence interruption group dropped from a team of 12 working in four focus areas across the city to a team of just four working in two focus areas today.

But violent crime in the areas they worked decreased by 22% over those two years, the organization says. Both it and city officials say they hope to work together again.

An old-school stakeout

On a quiet, warm February morning on Ferguson Road in East Dallas, the last police officers are moving into position.

Major Scoggins is watching from an unmarked car as a skinny young man in shorts and a beanie sweeps the sidewalk outside a convenience store. Across the street, a teenage boy ambles along the sidewalk, sits at a bus stop, and glances left and right.

For all the new emphasis on light-footprint policing and community partnerships, today’s operation is an old-fashioned stakeout. A team of police officers, many in plainclothes and unmarked cars, is waiting to make its move to disrupt the area’s destructive fentanyl trade.

Suddenly, the officers descend. But even that is quiet. They stop and frisk a few of the men outside the convenience store, including the sweeper.

Plainclothes officers talk with the suspects, asking for information. Others search them, unsuccessfully, for fentanyl. The officers discover the sweeper has an outstanding warrant for arson, and proceed to arrest him. Residents of nearby apartment complexes stop to watch and then move on. There are morning errands to run, and this street corner is no stranger to crime and violence.

It’s the kind of policing that has generated national controversy in recent years. But residents here have long complained about not having enough police around as dealers peddle drugs and fight for turf.

“The people that are there that are not contributing to the crime, they’re just trying to live their normal lives,” Major Scoggins says. “They know why we’re there, and they’re thankful. But then we also need to show how invested we are in that area to make it a safe place for citizens to live.”

Still, the tensions between police and high-crime communities remain a critical issue for departments across the country, experts say. But the kinds of new approaches in Texas and other states are striving to fight violence with more than police work and criminal convictions.

“In the past, it was always about relying on policing,” says Thaddeus Johnson, a fellow at the Council on Criminal Justice and an assistant professor at Georgia State University. “But how do you make sure you have a system that salvages life rather than destroys it?”

Editor's note: This story has been updated to clarify the organizational structure of Dallas Cred. It is a local organization supported by the national nonprofit Youth Advocate Programs Inc.

Today’s news briefs

• Hamas agrees to cease-fire deal: Hamas announces it has accepted an Egyptian-Qatari proposal for a cease-fire to halt the seven-month-long war with Israel in Gaza.

• Israel continues Gaza push: Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu says his wartime Cabinet approved continuing an operation in the southern Gaza city of Rafah.

• Chinese leader in Paris: French President Emmanuel Macron welcomes China’s Xi Jinping for a two-day state visit.

• Panama presidential race: José Raúl Mulino, the stand-in for former President Ricardo Martinelli in Panama’s presidential election, is set to become the new leader of the Central American nation.

In US, grim headlines for electric vehicles don’t tell the whole story

In our next two stories, we look at the electric vehicle industry from two different perspectives. In the United States, recent news has been bad. But behind the headlines, evidence points to an industry that’s actually continuing to grow.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Some recent reports point to electric vehicles being in trouble. From Ford’s financial losses on its much-hyped electric F-150, to questions about the real eco-friendliness of EVs, to recent news of Tesla’s mass layoffs, the take-away seems to be that the electric revolution is stalling.

But it’s not.

EV sales are continuing to grow rapidly in the United States and abroad, the technology is evolving briskly, and everyone from policymakers to auto executives to consumers is putting EVs at the center of long-term planning. Experts say a transition from a transportation sector based on the internal combustion engine to one that is electrified is all but inevitable.

“The trajectory is clear,” says Gernot Wagner, a climate economist at Columbia Business School. “None of this is ‘if’; it is ‘when.’”

But the speed and smoothness of the transition isn't clear. How it takes shape has a slew of implications for American workers, international trade, domestic policies – and the Earth’s climate. The spate of recent negative news points to the difficulties inherent in making a complicated shift to a still-developing technology.

In US, grim headlines for electric vehicles don’t tell the whole story

Given recent headlines, one might be excused for thinking electric vehicles are in trouble.

From reports about Ford’s financial losses on its much-hyped electric F-150, to questions about the real eco-friendliness of EVs, to recent news of Tesla’s mass layoffs and questions about its supercharger program, the take-away seems to be that the electric revolution is stalling.

But it’s not.

The reality is that EV sales are growing rapidly, the technology is evolving briskly, and everyone from policymakers to auto executives to consumers is putting EVs at the center of long-term planning. Experts say a transition from a transportation sector based on the internal combustion engine to one that is electrified is all but inevitable.

“The trajectory is clear,” says Gernot Wagner, a climate economist at Columbia Business School. “None of this is ‘if’; it is ‘when.’”

According to a new report from the International Energy Agency (IEA), the first quarter of 2024 saw a 25% growth in global EV sales over the same time period in 2023. That may be slower than the year before, and the slowdown was sharper still in the United States, but the overall pace is still impressive, experts say, and expected to continue.

“It’s not like automakers are saying, ‘Oh, we’re going to go back to internal combustion engine vehicles,’” says Joel Jaeger, senior research associate for the World Resources Institute’s systems change lab and climate program. “They’re just taking a little longer to get to their EV plans.”

But how much longer, and how that transition takes shape, has a slew of implications for American workers, international trade, domestic policies – and the Earth’s climate. The spate of recent negative news points to the difficulties inherent in making a complicated shift to a still-developing technology.

Heading toward an EV mass market

The transportation sector is the largest source of direct greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., according to the Environmental Protection Agency. That’s largely from gasoline exhaust. But some critics point out that emissions also occur in car manufacturing, including for EVs, and there are negative environmental impacts from lithium and rare-earth mineral mining. Still, despite increasing questions about the green credentials of EVs, multiple studies show that over their life spans, EVs have a lower climate impact than fossil fuel-based cars.

“You’ll still have some remaining emissions,” says Sergey Paltsev, a senior research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who is deputy director of the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change. “You need to mine the elements. You need to transport them. You need to produce a battery, you need to produce a car, and you need to also transport that car. ... Still, if you compare the overall emissions in the life cycle of an internal combustion vehicle to an electric vehicle, it’s clear that electric vehicles are better.”

The difference becomes even starker when a consumer uses renewable energy sources for electricity, he says.

But how quickly Americans will embrace this cleaner tech is unknown. Mr. Jaeger says the American EV market seems to be following an “S-curve” typical of many new technologies. Early adopters rush to buy the cool new thing at a high cost, sales growth slows until manufacturers can produce the technology more efficiently, and then the mass market begins to purchase the item and sales increase again.

That mass market adoption has already started in China, which in many ways has had a head start on EVs, investing years ago in battery plants, charging networks, and EV subsidies. More than 40% of Chinese car purchases in 2024 will be electric, according to the IEA. (In the U.S., the group projects, that number is 11%, and it’s 25% in Europe.)

Part of this is because of cost, analysts say. Chinese automaker BYD, which temporarily passed Tesla as the global leader in EV manufacturing last year, offers electric models for less than $15,000. (Tesla CEO Elon Musk has announced that the company will have its own, lower-priced EV by 2025.) There are also far more charging networks in China. Using World Bank population data and IEA charging infrastructure data, Mr. Jaeger calculates that as of 2023, China had 191 public charging stations per 100,000 people, compared with 55 public chargers per 100,000 people in the U.S.

Charging networks: Federal dollars are flowing

Cost and range anxiety are two of the most-cited reasons that Americans shy away from EVs.

But Ingrid Malmgren, senior policy director for Plug In America, an EV advocacy nonprofit, says both of these challenges will lessen in coming years. The $7.5 billion allocated by Congress in 2021 for charging stations is starting to bear fruit, she says. The money has been distributed to the states, which are in turn starting to build out charging networks, which promises to reduce consumer worries about getting stuck with a depleted battery pack.

“Like any big infrastructure project, it’s just a slow process,” she says. “There’s a lot of groundwork that had to be laid. I expect for it to be ramped up from here.”

Indeed, the number of public chargers increased in the U.S. 43% between 2022 and 2023, according to the IEA. But they are unevenly spaced around the country, and drivers are still wary of charge times.

Over the past half-year or so, most automakers have announced that their cars will be compatible with the Tesla supercharging system, now called the North American Charging Standard, which was originally only for Tesla vehicles. The move paves the way for more universal and faster charging, analysts say – although many are also wondering about the impact of Mr. Musk’s recent decision to lay off most of the team dedicated to making those superchargers. The Tesla CEO hasn’t publicly explained his move, but has said he was going to go “hard core” on staffing to balance lower sales numbers.

Meanwhile, there is continued work on both motor and battery technology, says Matthias Priendl, associate professor of power electronic systems at Columbia University. Research teams across the country are devoted to reducing or eliminating some of the rare-earth minerals currently used in battery production, and to developing motor technology that will continue to expand the range of EVs.

“The exciting thing about electric vehicles is that we’re still at the early stages of mass production and scaling up,” he says.

Risks if carmakers pivot too quickly – or too slowly

But that early stage has left American automakers with a challenge. They can push to quickly scale up EV production with current technology and risk getting ahead of supply chains and consumers. Or they can make a slower transition, with the hope of a more streamlined process in the future, but delay the cost benefits of large-scale production and risk losing customers to Chinese competitors.

“It’s a really important moment right now for the automakers,” says Ian Greer, a research professor at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations. “And they don’t have much time to figure this out before their competitors find strategies that work to mass-produce EVs for North America and European markets.”

The fear of a rapid transition goes beyond profits. Existing autoworkers in internal combustion engine plants worry about losing jobs – and Congress has not acted to protect workers, says Dr. Greer.

Meanwhile, some Americans worry that the federal government is going to ban their gas-powered trucks and cars – a concern seized upon and repeated by some politicians even though experts see no such move occurring. (Indeed, even if automakers rapidly transitioned to EVs, the existing gas-powered fleet would stay on the road for years, if not decades, Mr. Jaeger points out.)

The real mindset shift may come as more Americans drive EVs themselves, Ms. Malmgren says – something she sees happening as more people give electric cars a test drive.

After she leased her first EV, she never went back, and not just for the environmental reasons.

“The technology, the efficiency, the performance – there’s just no comparison,” she says. “I think change is a little messy sometimes. And it can be a little scary for people. But it can end up being wonderful.”

How China’s electric vehicles are dominating the industry

Our second story sees a different scene in China. The electric vehicle market is booming, with the Chinese auto industry on the rise. That worries automakers elsewhere, but it could benefit consumers.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

At Beijing’s glitzy auto show, enthusiasm over China’s homegrown electric vehicles was unmistakable.

“I’m interested in cars with more AI,” says Ying Cheng, a company worker shopping for a family car. He isn’t considering any foreign brands.

China has rapidly emerged as the world’s biggest EV market, accounting for about 60% of global sales in 2023. Domestic automakers are increasingly dominating that market while also racing to expand around the world. China’s EV exports shot up 77% last year, and Shenzhen-based BYD is now the world’s second-ranked seller of battery electric vehicles, after Tesla.

Chinese EVs are growing more technologically advanced and better designed – all while becoming more affordable, thanks to an estimated $139 billion in government subsidies to the EV sector.

As foreign brands scramble to regain ground in China, Brussels and Washington are weighing new tariffs aimed at preventing an influx of cheap Chinese EVs that could overcrowd local markets and lead to price distortions. Yet experts say keeping out Chinese EVs could also slow needed innovation by U.S. and European producers.

In France on Monday, Chinese leader Xi Jinping argued that China’s vast output of new energy products – such as solar panels, batteries, and EVs – alleviates inflation and contributes to the global push for greener policies.

How China’s electric vehicles are dominating the industry

Chinese car enthusiasts thronging to Beijing’s glitzy auto show – the country’s largest – had hundreds of sleek high-tech electric vehicles to explore last week from both foreign and domestic brands.

But as the crowds flocked to see the latest models, from the bestselling BYD Seagull to the sporty and digitally connected Xiaomi SU7, enthusiasm over China’s homegrown EVs was unmistakable.

“Smart cars produced in China are relatively advanced now,” says Ying Cheng, a Beijing company worker shopping for a family car. “I’m interested in cars with more AI.”

Mr. Ying isn’t considering any foreign brands, he says, because “their driving technology systems are relatively backward.”

China has rapidly emerged as the world’s biggest EV market, accounting for about 60% of global sales in 2023, compared with 25% in Europe and 10% in the United States, according to the International Energy Agency. Last year, Chinese consumers bought more than 8 million EVs, up 35% from 2022, and EVs are expected to make up 50% of all car sales in China by 2030.

Domestic EV-makers are increasingly dominating the Chinese market while also racing to expand exports around the world. China’s EV exports shot up 77% last year, to 1.2 million cars, according to official data. Shenzhen-based BYD is now the world’s second-ranked seller of battery electric vehicles, after Tesla.

The success of Chinese EV-makers is sparking concern over a potential flood of inexpensive Chinese EVs to the U.S. and Europe – including in France, where Chinese leader Xi Jinping began his first trip to Europe in five years on Monday. Seeking to head off a trade war, Mr. Xi told French President Emmanuel Macron and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen that China’s vast output of new energy products – such as solar panels, batteries, and EVs – alleviates inflation and contributes to the green transition, a global push for more sustainable policies.

“The so-called ‘problem of China’s overcapacity’ does not exist, either from the perspective of comparative advantage or in light of global demand,” Mr. Xi said, according to an official Chinese statement on his remarks. China and Europe should “address economic and trade frictions through dialogue,” he said.

What Chinese buyers look for

Chinese EVs are gaining appeal as they become more technologically advanced, better designed, and equipped with stronger batteries that charge faster – all while becoming more affordable. The popular BYD Seagull, for example, starts at less than 70,000 RMB ($10,000).

American brands such as Buick still enjoy a good reputation in China for safety and quality. But to thrive in the dynamic Chinese market, they will have to win over increasingly picky customers like Jia Yuzhen.

“I look for color and appearance, accessories and decor that are refined and high-end,” says Ms. Jia, a Beijing business owner, as she hops into the newly unveiled royal-blue Buick luxury van. She adds that seat comfort, safety, and “driving feel” are also key.

“Overall,” she says of the nearly $70,000 plug-in hybrid, “it’s pretty good.”

In a sprawling new plant in China’s southern Anhui province, armies of orange robotic arms twist, whir, and clank, producing Volkswagen’s latest EVs for the Chinese market.

The high-tech facility, which began operations late last year, is a critical hub for speeding to market smart EVs as part of the German brand’s “In China, for China” strategy. It aims to sell 1.5 million EVs in China per year.

“Chinese customers are different,” says Volkswagen (Anhui) Automotive Co. CEO Erwin Gabardi, noting that most are young, first-time buyers who want modern designs, connectivity, assisted driving, and in-car entertainment. “They want to maybe stay in the car for 30 minutes and do some meditation ... or do KTV [karaoke] songs together while they are driving.”

To innovate and advance in China’s ultracompetitive market, Volkswagen and other foreign car companies are increasingly partnering not only with local EV manufacturers but also with Chinese tech companies. Tesla last month won Beijing’s approval to launch its autonomous driving software in China using navigation provided by Baidu, the big Chinese search engine firm. And Toyota is working with the Chinese social media giant Tencent on integrating artificial intelligence and cloud computing in EVs.

Volkswagen, which has long dominated the Chinese car market, has seen its share shrink in recent years. It’s teamed up with Chinese firms making software, AI, and high-tech EVs to try to regain ground.

“Volkswagen wants to remain the No. 1 international OEM [original equipment manufacturer] in this country,” says Dr. Gabardi.

Yet whether foreign auto companies can fend off the onslaught of Chinese-made EVs is an open question.

Where China sends its excess cars

Chinese EV-makers are working hard to expand sales overseas – a necessity as the domestic market is not big enough to absorb the country’s massive EV production capacity.

At Great Wall Motor Co. in Baoding, Hebei province, Liu Huaxue, GWM’s vice president for operations, shows off a silver Ora “Lightning Cat” EV, the company’s new fully electric sedan marketed for China, other parts of Asia, and Europe.

“We want to expand everywhere,” says Mr. Liu.

China’s government channeled an estimated $139 billion in subsidies and other support for the domestic EV sector from 2009 to 2021, part of an expansive industrial policy aimed at dominating key technologies, according to research by Scott Kennedy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

That policy gave Chinese EV-makers a big lead over foreign rivals. But it also led to market distortions and inefficiency – spurring enormous overcapacity by a crowded field of some 200 producers – causing an ongoing price war that has slashed EV prices since 2022.

It’s a major source of rising trade friction with the U.S. and the European Union, which last October launched an antisubsidy investigation into Chinese EV firms. Both Brussels and Washington are weighing new tariffs aimed at preventing an influx of cheap Chinese EVs, which are already subject to a 25% tariff in the U.S.

Yet keeping out the Chinese EVs could also slow needed innovation by U.S. and European EV producers, while hurting consumers in those markets, says Dr. Kennedy.

Beijing has cast Western countries’ concerns as veiled protectionism and in February mobilized government ministries to help China’s EV-makers fight foreign restrictions.

GWM’s Mr. Liu sees potential Western tariffs as “a big challenge.”

Like other Chinese EV-makers, he says GWM is looking at building new production facilities outside of China to avoid the tariffs. “In the future, we can build a local plant in Europe,” he says. “That’s about the only option.”

Indeed, as Mr. Xi began his trip to Europe, French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire told reporters that BYD would be welcome to open a factory in France. But both Mr. Macron and Ms. von der Leyen stressed to Mr. Xi that Europe seeks fair trade with reciprocal market access.

Europe “will not waiver from making tough decisions needed to protect its economy and security,” Ms. von der Leyen said after the meeting, according to The Associated Press.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct the estimated subsidies the Chinese government gave to the EV sector.

Commentary

NBA playoffs without Curry? James? Durant? A new guard rises in basketball.

The NBA playoffs without the league’s superstars represents an important reminder in life – when we obsess over the past, we miss out on the greatness that is happening in the present.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

For the first time in 15 seasons, the second round of the NBA playoffs will be without the familiar trio of LeBron James, Stephen Curry, and Kevin Durant. Fans of the NBA seem to have great difficulty with letting the past go, but much like in life, I have come to embrace such change.

Society often talks about legacy, but rarely about lineage. Michael Jordan made way for Kobe Bryant and seems to have an heir in Anthony Edwards, who wrested his first-round playoff matchup from Durant and the Phoenix Suns with an unmistakable competitive fire.

As the global games approach this summer, there are other similarities – and opportunities to mold and meld greatness across eras. James, Curry, Durant, Edwards, and Jayson Tatum will join a collection of players that will represent the United States at the 2024 Olympic Games. The 1992 roster, better known as the Dream Team, was a coming-out party of sorts for Michael Jordan, who shone amid the end of an era for luminaries such as Magic Johnson and Larry Bird.

Ultimately, pro basketball is a reminder of not only how things change, but the duality of what it means to “pass the torch.”

NBA playoffs without Curry? James? Durant? A new guard rises in basketball.

LeBron James’ basketball career has always been paradoxical with respect to time, whether it was his rise through the NBA ranks as a teenager, or how he remains one of the game’s great players upon the completion of his 21st season.

The way that campaign ended, along with those of some of his peers, represent a stunning changing of the guard. Despite the best efforts of James and the Los Angeles Lakers, they were vanquished by one of James’ admitted understudies, the Denver Nuggets’ Jamal Murray.

Murray hit two game-winners during the course of a first-round, five-game playoff series, which the Nuggets won 4-1. Stephen Curry and Kevin Durant, both generational talents, were similarly taken down by players who looked up to them years ago, specifically, the Sacramento Kings’ De’Aaron Fox and the Minnesota Timberwolves’ Anthony Edwards.

For the first time in 15 seasons, the second round of the NBA playoffs will be without the familiar trio of James, Curry, and Durant. Fans of the NBA seem to have great difficulty with letting the past go, but much like in life, I have come to embrace such change.

The morning after Murray’s second game-winner, I received a message from a college buddy who floated the idea of a James-Curry-Durant team-up. “There’s one obvious way to extend this era,” he insisted.

The insistence to maximize the primes of the trio sounded like the musings of fans who clamored for Michael Jordan after his second retirement in 1999. Even now, the legendary standard Jordan set has infringed on the greatness of James, as the two often end up in (inane) debates about who is the “greatest of all time.”

Jordan’s twilight and the downslope of James’ career represent an important reminder in life – when we obsess over the past, we miss out on the greatness that is happening in the present. As a person who studies and appreciates history, I understand this requires great balance. And yet I believe the greatest zen happens when we allow the past to inform the present and future, not overtake it.

Basketball is best when we appreciate the contributions of all of its stars, much like in a free-flowing offense. This allows for a generational perspective that is productive and healing – like the changing of seasons. With respect to Murray’s heroics, the best player on the Nuggets is Nikola Jokić, a native of Serbia whose dominance has become harder and harder to deny over the past few years.

In addition to Jokić, other players vying for the league’s most valuable player are of foreign descent – the Oklahoma City Thunder’s Shai Gilgeous-Alexander, a native of Canada, and Luka Dončić, who is from Slovenia. And the Boston Celtics’ Jayson Tatum has been on the cusp of greatness for close to a decade, himself a wunderkind in the mold of the late, great Kobe Bryant.

Society often talks about legacy, but rarely about lineage. Jordan made way for Bryant and seems to have an heir in Edwards, who wrested his first-round playoff matchup from Kevin Durant and the Phoenix Suns with an unmistakable competitive fire. Poetically enough, it was Durant who teamed with a young Russell Westbrook to overtake Bryant’s Lakers in the 2010s.

As the global games approach this summer, there are other similarities – and opportunities to mold and meld greatness across eras. James, Curry, Durant, Edwards, and Tatum will join a collection of players that will represent the United States at the 2024 Olympic Games. The 1992 roster, better known as the Dream Team, was a coming-out party of sorts for Jordan, who shone amid the end of an era for luminaries such as Magic Johnson and Larry Bird.

Ultimately, pro basketball is a reminder not only of how things change, but also of the duality of what it means to “pass the torch.” It is not always a gracious process, as evidenced by the competitive fires of a generation of greats being extinguished relatively early. And yet, this is the ultimate form of respect to players such as James – imitation being the sincerest form of flattery.

Benevolence doesn’t always manifest itself in the field of play or in the final score, but we have the option to reflect on the good and bad with gratitude. Oftentimes, during various media opportunities, James will wear a shirt that says “More than a game.” This is where sports might be at its greatest – beyond individual and remarkable athletic exploits, and representative of ideals which can help us all.

Points of Progress

Housing projects: Paris curates its streets, and Navajo homes get addresses

Our progress roundup looks at two places people call home and what is being done to enhance life in each. For some Navajo residents, new, reliable street addresses smooth the path to voting. And in Paris, public housing is a sought-after commodity.

Housing projects: Paris curates its streets, and Navajo homes get addresses

Navajo Nation residents in Utah received accurate new home addresses to strengthen voting rights

Rural communities often rely on step-by-step, descriptive addresses to access services. But this can lead to logistical snafus, such as emergency vehicles’ delayed response.

Using Google’s open-source Plus Codes, the Rural Utah Project has helped register over 9,000 rural voters, which includes more than 3,100 new addresses for Navajo residents.

Plus Codes are simple combinations of letters and numbers that can be generated for any place on the planet. The United States Postal Service does not recognize Plus Codes, but users have found them beneficial for receiving private parcels and even health care services.

Daylene Redhorse, the project lead in Navajo Nation, fought for the trust of Native Americans, who didn’t have suffrage in every state until the 1960s. Another group, the Navajo Nation Addressing Authority, is working on getting streets named throughout the reservation.

Sources: The Daily Yonder, Yes! Magazine, Rural Utah Project

A women-run city bus program serves one of the poorest areas of Colombia’s capital and is turning a profit

Instituted by term-limited former Mayor Claudia López, the initiative began in 2022 as part of a broader effort to tackle lack of gender equity in Bogotá. The fleet of 195 vehicles is the second-largest electric fleet outside of China.

Sixty percent of La Rolita’s 500 drivers are women, and the program reports fewer accident-related injuries than private bus operators in Bogotá do. General manager Carolina Martinez said that women may feel safer with female drivers in a city where 84.3% of women report experiencing sexual harassment on public transit. Over 100 of the program’s drivers use flexible work hours to care for their families or pursue higher education.

Some drivers say they’ve encountered sexist attitudes from male passengers. Yet La Rolita garnered a 91% satisfaction rating in a city survey, compared with 29.7% for other bus services in Bogotá.

Source: Reasons to Be Cheerful

Under the mixité sociale (diversity) policy, Paris works to keep the city affordable and maintain its character

While property prices have dropped slightly in recent years, the average price for a 1,000-square-foot apartment is €1.3 million ($1.41 million). Today, one-quarter of Parisians live in government-owned housing, and the demand is increasing, with a waitlist of six years. The city can legally buy most properties for sale for conversion to public housing, and has renovated or built more than 82,000 apartments for families in the past three decades.

From florists to bookstores, the city tries to maintain a mix of small businesses in each neighborhood. Paris is landlord to 19% of its shops, which enjoy below-market-rate rent.

Though mixité sociale is expensive, policymakers on the left and right generally agree on its benefits.

“A city, if it’s only made up of poor people, is a disaster,” said Benoist Apparu, a former housing minister in a conservative government. “And if it’s only made up of rich people, it’s not much better.”

Sources: The New York Times, Bloomberg

A fellowship program in Nigeria trains women journalists in investigative reporting

A 2017 survey of 85 Nigerian newsrooms found that men held the vast majority of editorial leadership positions, with a ratio as high as 10 to 2. The Women Radio Centre’s annual workshop provides mentorship, coaching, and resources to support investigative stories.

In 2022 the first weeklong residential program was supported by the MacArthur Foundation, after which participants were given laptops and other tools to aid them in their investigations. For the latest class, the three-day session concluded with each fellow receiving a grant to support future reporting.

The program has limited space, selecting only 20 out of 1,552 applicants from around the country in 2023. It is “a beautiful place to learn, make friends, and network,” said Angela Nkwo-Akpolu. “Embrace it, give it your best, I assure you the benefits will be limitless.”

Sources: BoNews, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Solutions Journalism Network

With more Māori designs in the landscape, New Zealand celebrates Indigenous architecture and culture

Making up 17% of the population, the Māori are the country’s largest nonwhite ethnic group.

In the suburbs of Auckland, a new meeting house and education center – Taumata o Kupe – soars into the sky. The building’s sail-shaped form and decoration include the story of the first Māori arrival in what is now New Zealand.

Using funds from a settlement with the government, one North Island tribe has built award-winning affordable housing for its members, with features such as shared gardens and playgrounds. Jade Kake, an Indigenous architect whose firm is north of Auckland, designs homes for collective living, where the structures can accommodate changing family patterns.

Auckland’s city council adopted a series of Māori architecture principles in 2016. “The principles can be misused,” said Ms. Kake. “But it’s more about the process than the product, ensuring that the consultation and co-design process is meaningful.”

Source: The Guardian

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The alternative to campus protests

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Just months before the Oct. 7 attack on Israel, Muslim and Jewish students at Middlebury College set up a dialogue. They agreed to exchange any and all views on Israeli-Palestinian issues. After the attack, their bonds were already so tight that they raised money to feed the people of Gaza by selling bread.

“The students were the model for us,” said Laurie Patton, president of Middlebury. True to the spirit of academic freedom, the students engaged in civil discourse and open inquiry, based on a respect for each other’s inherent dignity.

Journalists covering the campus protests over Israel’s actions in Gaza are beginning to notice that many schools have long taken a different tack on the issues in the Middle East. Instead of a climate of confrontation, students and teachers seek to stretch their thinking without fear of reprisal.

In recent weeks, a number of universities have affirmed the need to offer a neutral forum for students to learn the skill of navigating differences. Not all ideas are equal, and some may need tough scrutiny. But equality within a community of thinkers defines a university. It might even compel some to bake bread for others.

The alternative to campus protests

Just months before the Oct. 7 attack on Israel, Muslim and Jewish students at Middlebury College in Vermont set up a dialogue. They agreed to exchange any and all views on Israeli-Palestinian issues. After the attack, their bonds were already so tight that they raised money to feed the people of Gaza by selling bread.

“The students were the model for us,” Laurie Patton, president of Middlebury, said at a recent panel organized by Interfaith America. “Are there still tensions? Absolutely. But that kind of work was possible because they had a relationship. And they had been brave together.”

True to the spirit of academic freedom, the Middlebury students engaged in civil discourse and open inquiry between equals, based on a respect for each other’s inherent dignity. Providing such tools to students, said Dr. Patton, “is our moral obligation as educators.”

Journalists covering the campus protests over Israel’s actions in Gaza are beginning to notice that many schools have long taken a different tack on the difficult, complex issues in the Middle East. Instead of a climate of confrontation, students and teachers seek to stretch their thinking on such issues without fear of reprisal. As The Guardian newspaper discovered, the protests have led to “an undercurrent of more nuanced, private conversation, as students from different backgrounds try to navigate their own identities and have an impact on a devastating war happening a world away.”

The newspaper found a few Jewish and Palestinian American students at the University of California, San Diego have forged a friendship by subjecting their views to criticism in order to find common ground. At Yale University, graduating senior Ian Berlin wrote for CNN that he found “a community of activists and organizers that is eager to listen, ready to learn and committed to including Jewish voices and perspectives.”

At Johns Hopkins University, Professor Steven David has taught a course on Israel’s future since 2016. It pushes students of all backgrounds to listen to competing and perhaps repugnant arguments while also accepting the consequences of their own views. His tactics help students be “less polemical and in some ways less intense, recognizing that there are many sides to these problems,” he told The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Such intellectual humility in the pursuit of truth is the essence of higher education. And perhaps needed more than ever.

A recent study by three university scholars looked at 40 institutions, organizations, and groups of professionals, from Facebook to scientists, and found that such groups were less trusted by the public when they were perceived as ideologically biased. That was true even “among participants who perceived the institutions as aligned with their own ideology.”

In recent weeks, as the protests have escalated, a number of universities have affirmed the need to offer a neutral forum for students to explore ideas and learn the skill of navigating differences. Not all ideas are equal and some may need tough scrutiny, especially those based on antisemitism. But equality within a community of thinkers defines a university. It might even compel some of them to turn their shared discoveries into baking bread for others.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Stepping out of chaos

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Rich Evans

As we let the divine Mind, God – rather than fear and turmoil – inform our thoughts and view of the world, we find that light, joy, and harmony increasingly characterize our experience.

Stepping out of chaos

Is there a way out of chaos and into order and harmony? The present need for that is acutely felt and deeply sought everywhere. But in searching for such a path in the midst of a disordered world, is it possible that chaos itself could be a harbinger of the peace we yearn to see?

The promise of that is found in this remarkable statement by Mary Baker Eddy in her book “Unity of Good”: “The chaos of mortal mind is made the stepping-stone to the cosmos of immortal Mind” (p. 56).

Maybe chaos nudges a natural desire in us to step away from it. In order to be free of the exhaustion of inharmony, it is natural – spiritually innate – for us to seek something else, to reverse direction, to move toward safer, more peaceful ground. There we can begin to see the opposite condition, the orderly, harmonious universe – the cosmos – of immortal Mind, God. Dissatisfaction with the materialistic, chaotic life arising from the limitations of a material mentality that would seem to veil the divine Mind becomes a strong impetus to move in the opposite direction.

For example, if we feel hated or hateful, we can remove that sense by turning directly to divine Love, God, and expressing such love that it pulls us and others out of discord and inharmony. It doesn’t matter how often we feel the need to reverse our course of thought and action, because this powerful sense of Love is Principle and therefore always at hand and active.

If attentive, we can detect early the fear that underlies chaos or hatred and let our thoughts be informed by divine Mind in a peace-generating direction. No chaotic, mortal mind can influence our life to blur our vision of the true course leading to freedom, accord, and stability.

In “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mrs. Eddy articulated her discovery – the divine laws that governed Christ Jesus and enabled him to do the works of primitive Christianity, preaching and proving the laws of God. Those laws govern us today.

In this book, we’re asked if we have accepted the mortal model of ourselves and others that the world holds before our gaze. Perhaps this model appears as the chaos of matter-based living that could seem as attractive as it is frightening. But that model is imperfect. It can be vicious and hideous and can limit our lifework and our view of humanity. The remedy is evident: “... we must first turn our gaze in the right direction and then walk that way” (p. 248).

What a word, “gaze.” Beyond merely looking or seeing, there is intention in gazing. Gazing at stars, we’ve chosen to discover something new to us – a constellation, satellite, or aurora. Or, closer to us, gazing through the lens of Spirit, we discern humankind’s amazing, infinite individuality.

Where should we be gazing to reverse our drift toward the mortal model, the darkness and chaos of world belief that would trap humanity in the apparent reality of matter and its conflicts? The reverse, the perfect model, is “unselfishness, goodness, mercy, justice, health, holiness, love – the kingdom of heaven” reigning within all of us (Science and Health, p. 248). There’s nothing chaotic about any of that; in fact, as these divine qualities are lived, discordant conditions lose their influence until they disappear.

Why? Darkness and chaos have no place in God, Mind, and the infinite harmony and order that are actually present. When we turn our gaze toward God, we find that Mind’s light and joy overtake and exclude the darkness and sorrow of chaos. Then chaos has been made our steppingstone to the cosmos, the ever-present and immortal harmony of divine Mind, and no longer causes fear.

A scriptural example of turning one’s gaze in the right direction is Saul, later known as Paul (see Acts 9:1-20). He was afraid that the new teachings of Jesus would disrupt the world he knew. He sided with the suppressors of a dawning Christianity.

But his own moment of awakening, turning his gaze toward Christ and finding light in the midst of darkness, led to a lifetime of sustained expansion of the power of Christ-love and its peace. This was the new order – the true cosmos of divine Mind – the spiritual reality toward which to set our gaze, one that the transformed Paul never failed to pursue and prove.

We needn’t fear chaos. Instead, we can see it as the harbinger of a change in direction, of a step for us all toward immortal Mind’s order and harmony.

Adapted from an editorial published in the April 1, 2024, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

My kingdom for a crumpet

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. We hope you will also join us tomorrow at 11 a.m. Eastern time for our Facebook Live event. I’ll talk with Alexandra Hudson, author of “The Soul of Civility: Timeless Principles To Heal Society and Ourselves,” about the intersection of civility and trust. We’ll explore how they shape our views of the world, and how to put them into practice every day.