- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- The job market needs workers. The newest ones are over age 75.

- Today’s news briefs

- In China, a triumph of quiet diplomacy

- Why Mexican judicial reform is causing a rift with the US

- ‘Five feet from the president’: Watching history unfold as the press pool reporter

- For this affordable-housing advocate in Ontario, tiny homes are where the heart is

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

We rarely mention ages. The rest of journalism is beginning to understand why.

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

For as long as I’ve been at the Monitor, we’ve preferred not to mention people’s ages unless it’s essential. Age tends to define people, often poorly. Today’s story by Laurent Belsie beautifully explores this topic.

Recently, I’ve seen commendable efforts by journalists to broaden this principle. Convict, addict, illegal immigrant – these terms and others, like age, tend to remove humanity, agency, and nuance. To me, looking for better ways to talk about our fellow human beings is not about a political agenda, but about good journalism.

Perhaps more than ever, societies are learning that labeling people is unhelpful, not only to the person but also to our own understanding. Laurent’s story clearly shows why.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

The job market needs workers. The newest ones are over age 75.

Narratives of “too old” have become ubiquitous among pollsters, politicians, and pundits. But on Main Street, the hottest growth in the labor force is among workers well past traditional retirement age.

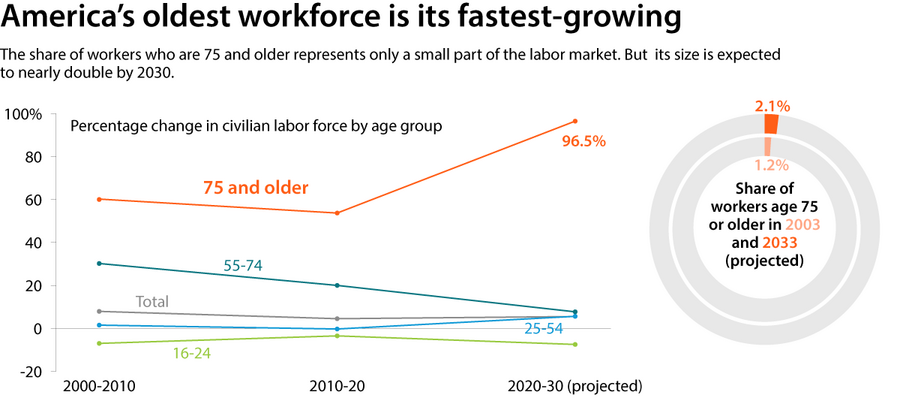

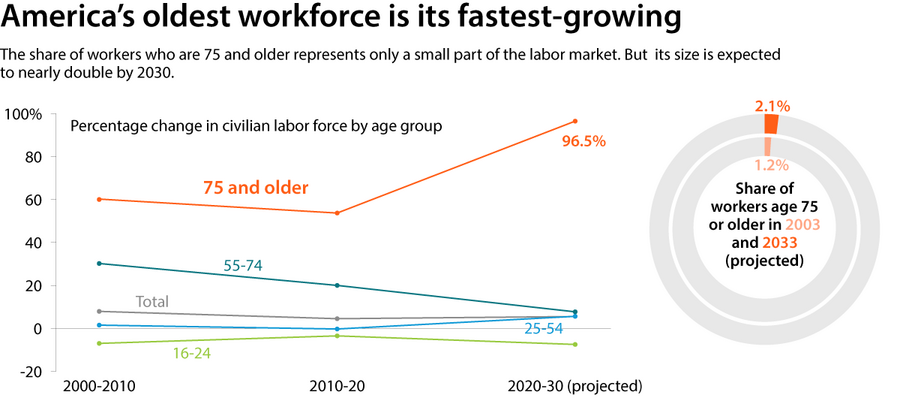

At a time when America’s political class has decided some people are too old to be president, the economy is pointing in another direction: The fastest-growing segment of the labor force is the 75-and-older worker.

While much of that growth is simple demographics – many baby boomers are moving into their 70s – it doesn’t appear to explain the entire phenomenon. For many Americans, working well into one’s 70s, 80s, or even 90s now seems preferable to full retirement.

This surge in older workers is a boon to the United States as well as developed nations around the world. Still, the negative stereotyping based on age – known as ageism – persists.

That has not slowed down Pat Callahan, who, like many Americans, retired and then went back to work.

“This is my exercise,” says Ms. Callahan, who retired in her late 60s and a little over three years ago began working for her daughter’s startup, JM Move Managers, based in New Jersey.

Now in her mid-70s, Ms. Callahan spends 8 to 12 hours a week helping people discard or donate belongings. “I don't think I've ever worked a job where people are so grateful for your help.”

The job market needs workers. The newest ones are over age 75.

At a time when America’s political class has decided some people are too old to be president, the economy is pointing in another direction: The fastest-growing segment of the labor force is the 75-and-older worker.

By 2030, the federal government projects, their numbers will nearly double.

While much of that growth is simple demographics – a huge contingent of baby boomers is moving into their 70s – it doesn’t appear to explain the entire phenomenon. For a growing share of Americans, working well into one’s 70s, 80s, or even 90s seems preferable to a full retirement.

Some of them are famous, such as septuagenarian singer Dolly Parton and actor Meryl Streep, octogenarian actor Harrison Ford and musician Mick Jagger, and nonagenarian primate expert Jane Goodall and uber investor Warren Buffett.

“This is my exercise.” How older workers benefit the economy.

Then there’s Pat Callahan, who like many not-so-famous Americans retired and then went back to work.

“I’m not at the Y working out; this is my exercise,” says Ms. Callahan, who retired in her late 60s and a little over three years ago began working part time for her daughter’s startup, JM Move Managers. The Mountainside, New Jersey, company specializes in helping older people every step of the way as they downsize and move into new accommodations.

Now in her mid-70s, Ms. Callahan spends anywhere from 8 to 12 hours a week helping people discard or donate belongings, packing up what they want to keep and unpacking and organizing it in their new place. She even hefts boxes if they’re not too heavy, she says. “I don’t think I’ve ever worked a job where people are so grateful for your help.”

This surge in older workers is not unique to the United States. It provides benefits to developed nations around the world. It boosts the share of people contributing to the economy, provides needed workers at a time when some portions of the workforce are shrinking and, potentially, eases the pressure on retirement-benefits systems if it persuades governments to raise retirement ages.

Despite these benefits and the increasing visibility of people of traditional retirement age on the job, the negative stereotyping based on age – known as ageism – persists.

Learning to lift age-based labels

“Ageism is alive and well,” says Jacquelyn James, founder of the Sloan Research Network on Aging & Work at Boston College. “Anyone can make a joke about an older person. They’re a geezer, or they’ve ‘lost it.’ They can’t do the job or are slow. ... The discussion about [President Joe] Biden has probably set us back quite a bit.”

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

The problem, gerontologists say, is that rather than understanding physical and mental limitations as a specific challenge for a specific individual, such challenges are generalized as “getting old” and pinned to an entire segment of the population. The reality is quite different.

“I know a lot of guys who are in their early 80s who are still flying,” says Dana Lyon, a former Southwest Airlines pilot who at 65 took mandatory retirement and, 13 months later, started working again. In his late 60s, he now flies charter planes for a startup in Texas and plans to continue four or five more years, he says. “I love flying.”

While many of those working into their 70s have cut back their hours and consider themselves retired, some remain quite active. Bob Iger retired as Disney’s CEO at 70, spent less than a year in retirement and then returned to his post two years ago at the behest of the board of directors. At 84, Nancy Pelosi, while no longer speaker of the House, is active politically, and helped persuade President Biden, who is 2 ½ years younger, to end his reelection campaign last month.

More often than not, older people stay in their jobs rather than find new ones. This is especially true of professionals, such as lawyers and professors, as well as small-business owners, says Gary Burtless, a senior fellow emeritus at the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank.

Second and third careers

Job-seekers over age 65 have a hard time getting employers to respond to their applications, let alone offer them a job, says Ms. James at Boston College.

But there are exceptions.

At Stanford University’s Distinguished Careers Institute, experienced professionals leaving their primary career take a year to explore possibilities. A neuroscientist is now publishing her wildlife photography; a trial lawyer is writing mystery novels, according to Katie Connor, the institute’s executive director. After working as an environmental engineer, founding a coffee company in Hong Kong, taking time off to raise her children, lecturing at the University of Colorado at Boulder and eventually running its career office, Ms. Connor came to the institute to figure out her next step. It turned out to be heading up the institute.

Thinking outside the box is a big factor in a successful transition, she says, as well as “being curious and being willing to be a beginner. It can make all the difference. ... There are structural problems [for older job-seekers looking for a change]. But I also think there are problems in our own mindset about aging.”

Want to work versus need to work

The rise of older workers also has its darker side.

Roughly half of those on the job working past age 65 are working because they have to, not because they want to, says Craig Copeland, director of wealth benefits research at the Employee Benefit Research Institute, a policy research nonprofit in Washington. About 1 in 3 older adults is economically insecure, many of them Black or Hispanic, according to the Census Bureau.

Another downside is that boomers hanging onto higher, better-paying jobs can breed resentment among younger workers. “The young guys, they go: ‘You’re taking my spot. You’re an old man. Get out of there so I can move up,’” says Mr. Lyon, the pilot.

The visibility of such workers can increase envy and even ageism, especially if the older workers are struggling at their jobs, Teresa Ghilarducci, an expert on retirement security at the New School for Social Research in New York, writes in an email. But “on balance, older workers overcome ageism. [Ms. Pelosi] has never been more effective. ... She is old and probably still peaking.”

Editor’s note: The description of Stanford University’s Distinguished Careers Institute has been updated to be more precise, and to give the correct occupation of the person becoming a mystery writer.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Today’s news briefs

• Kashmir vote: Residents of Indian-controlled Kashmir are gearing up for their first regional election in a decade that will allow them to have their own truncated government, instead of remaining under New Delhi’s direct rule.

• German elections: Elections in two eastern German states Sept. 1 could make the far-right Alternative for Germany the strongest party for the first time.

• U.S. smoking policy: The health regulator of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has raised the age verification requirement from 27 years old to 30.

In China, a triumph of quiet diplomacy

President Biden’s national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, capped 15 months of secret diplomacy this week with a trip to Beijing that seems to have put China-U.S. relations back on an even keel.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Jake Sullivan, who is President Biden’s national security adviser, wrapped up a three-day visit to China Thursday that appears to have put Washington’s relations with Beijing back on an even keel.

The trip capped a series of secret meetings in different parts of the world that Mr. Sullivan has held over the past 15 months with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi. This week, he held unexpected talks with top Chinese leader Xi Jinping and landed a rare meeting with China’s most senior military officer.

Mr. Sullivan’s contacts with senior Chinese officials have led to the opening of communications channels in around 20 fields, from restoring military-to-military contacts to talks on artificial intelligence safeguards. A top priority has been to establish mechanisms to reduce the risk of misunderstanding and miscalculation between the two nuclear powers.

Neither side believes that their dialogue has resolved fundamental differences between them. “They need first and foremost to find a good answer to the overarching question: Are China and the United States rivals or partners?” Mr. Xi said.

But the progress he made convinced Mr. Sullivan that, in his words, “intense diplomacy matters. We are going to keep at it.”

In China, a triumph of quiet diplomacy

As Americans prepare to celebrate Labor Day, U.S. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan has been working overtime to keep the United States’ most crucial diplomatic relationship on an even keel.

Mr. Sullivan’s efforts paid off this week, as he made the first visit by a United States national security adviser to China in eight years, held unexpected talks with top Chinese leader Xi Jinping, and landed a rare meeting with China’s most senior military officer, General Zhang Youxia.

The three-day visit paved the way for a phone call in coming weeks between President Joe Biden and Mr. Xi, and for a possible in-person meeting later this year.

“Intense diplomacy matters,” Mr. Sullivan told a Beijing press conference as he wrapped up his visit late Thursday. His Beijing trip capped a series of unpublicized meetings he had held over the past 15 months with China’s top diplomat, Wang Yi.

During a U.S. campaign season in which many American politicians are hostile to China, this quiet diplomatic effort by Washington and Beijing has succeeded in reversing the past few years’ dangerous tailspin in relations between the world’s two superpowers, experts say.

Mr. Sullivan’s trip cements the idea that “talking to China … is not optional,” says Susan Thornton, a retired high-level U.S. diplomat and senior fellow at the Yale Law School Paul Tsai China Center. “It’s necessary for our national security,” she says. “It’s actually benefiting the United States” by fostering stability “in a world that’s looking more and more unpredictable,” she says.

Under-the-radar diplomacy works

In recent years, U.S.-China tensions have soared over Taiwan and the South China Sea as well as trade, technology, and China’s support for Moscow since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022. Meanwhile, face-to-face dialogues were hampered when China closed its borders to most foreign travelers for three years during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Messrs. Biden and Xi met in Bali, Indonesia, in November 2022 to try to put a floor under the collapsing relationship. They pledged to resume regular communications. But these efforts were disrupted by a new crisis in February 2023, when a Chinese surveillance balloon flew over the continental U.S., only to be shot down by the U.S. military.

In this context, Mr. Biden dispatched Mr. Sullivan to lead multiple rounds of low-visibility meetings with Foreign Minister Wang, starting in May 2023. The talks were “very detailed, painstaking” and “an all-hands-on-deck effort” by senior U.S. and Chinese officials, Mr. Sullivan told reporters.

This set the stage for a successful summit between Messrs. Biden and Xi in Woodside, California, in November 2023 and led to progress in critical areas – restoring military-to-military communications and launching talks on artificial intelligence safeguards, among other topics. In all, the two sides opened some 20 communications channels. More broadly, the diplomacy has reduced the risk of misunderstanding and miscalculation between the two nuclear powers. “We’re going to keep at it,” Mr. Sullivan said.

“Talking has been restored, and relations have been stabilized to some extent,” says Ambassador Huang Ping, the Chinese consul general in New York. “We know we cannot afford confrontation or fighting, so we have to work together to manage differences,” he says.

U.S. scores meeting with top Chinese general

One significant sign of headway in military-to-military ties was Mr. Sullivan’s unprecedented meeting Thursday with General Zhang, vice chairman of the Central Military Commission, China’s top military body.

“There is no substitute for … being able to sit across the table” from General Zhang and his team “to hear … their perspective on critical issues … whether it’s cross-Strait relations or the South China Sea,” said Mr. Sullivan. They agreed on a phone call between U.S. and Chinese theater commanders, a significant step to help operational-level commanders to avert or deal with any conflict.

Such contacts are vital, given the proximity at which Chinese and U.S. warplanes and navy ships conduct patrols at flash points such as the Taiwan Strait and South China Sea.

Vessels belonging to China and the Philippines, a U.S. treaty ally, have clashed recently near disputed shoals in the South China Sea. In Beijing, Mr. Sullivan reiterated the U.S. “ironclad commitment” to honor its mutual defense treaty with the Philippines. But he also stressed that “nobody is looking for a crisis” and encouraged direct talks between Manila and Beijing.

“Zhang Youxia is … a top-level military person within Xi Jinping’s circle and [U.S. officials] haven’t met with him before, so it’s very significant to have that first meeting,” says Ms. Thornton.

Fundamental differences remain

Both U.S. and Chinese officials acknowledge that the ongoing dialogues have not solved fundamental differences between them. Indeed, Mr. Xi stressed to Mr. Sullivan that China and the U.S. do not view the relationship the same way.

“The number one issue is to develop a right strategic perception,” he said, according to a Chinese government summary of his remarks. When the U.S. and China engage, he said, “they need first and foremost to find a good answer to the overarching question: Are China and the United States rivals or partners?”

Yet by committing to talks, Washington and Beijing have made headway in managing the relationship – both by avoiding misunderstandings and by anticipating potential problems before they arise.

The two sides “have a track record of trying to get ahead of periods that may add tensions and frictions,” says Brian Hart, a fellow with the China Power Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. For example, he says, “they knew 2024 would be a tumultuous year given the [presidential] elections in Taiwan and the U.S.”

China’s leaders “recognize that elections are sensitive periods,” Mr. Sullivan says, and Vice President Kamala Harris supports high-level communications between Washington and Beijing as a way to responsibly manage the relationship.

The extent to which current dialogues would continue under a potential second Trump administration, though, is unclear, experts say. “They’re much more leery about dialogues and talking to the Chinese,” says Ms. Thornton. If Mr. Trump is elected, “I think you’ll see some pressure to cut back on who is involved in communicating with China,” she predicts.

One trend that is not likely to change is the revival of people-to-people exchanges between the U.S. and China. “The lack of face-to-face engagement really creates trouble,” says Ambassador Huang. “The deficit of mutual understanding has gone so far, so we need to bring people together.”

The Explainer

Why Mexican judicial reform is causing a rift with the US

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador is pushing a controversial reform package through the legislature before leaving office. While he sees changes in how judges are selected as a win for democracy, others, including the U.S., fear the loss of a key independent institution.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Mexico’s new president takes office Oct. 1, and her predecessor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, is leaving her – and the country – a controversial constitutional reform package with which to contend. It includes significant changes to how judges are selected. If it’s approved by the ruling party’s legislative majority, as expected, judges will be elected by popular vote, instead of through professional exams and merit. Other reforms are proposed for public security and government oversight.

Proponents – including Mr. López Obrador’s vast base of supporters – say changes in how judges are selected will make the judicial system work better for average Mexicans, and allow Claudia Sheinbaum, the incoming president, the tools she needs to continue transforming the country.

Others worry it’s a political play.

“This is personal revenge against the justices of the Supreme Court” who have blocked Mr. López Obrador’s past attempts to change the Constitution, says Emiliano Polo, a Mexican lawyer and associate at the Mexican Council on Foreign Relations.

It caused a rift between the United States and Mexico this week, following the U.S. ambassador’s criticism that the reforms could undercut democracy and open up more opportunities for organized crime to meddle in the government.

Why Mexican judicial reform is causing a rift with the US

The United States and Mexico have had a conciliatory relationship for six years under President Andrés Manuel López Obrador. But weeks from leaving office, he has heralded a judicial reform that has generated rare public criticism from the U.S. ambassador – and provoked a rift in U.S.-Mexico relations.

Mr. López Obrador is widely popular, and the Mexican public broadly supports the reform.

But judges, law students, economists, human rights experts, and Mexico’s most important trading partners worry it could lead to democratic backsliding – and macroeconomic turbulence – that the incoming President Claudia Sheinbaum will inherit when she takes office Oct. 1.

What exactly is this reform?

The judicial reform, approved by a committee in the lower house of Mexico’s Congress this week, will be sent to the new Congress next month.

It’s part of a broader constitutional reform package and would overhaul how judges – from local levels to the Supreme Court – get their jobs. The system would move from appointing justices based on their training and qualifications to letting citizens decide some 7,000 judge, magistrate, and justice positions by popular vote.

Mr. López Obrador’s term has been defined by his desire to transform the nation. He rose to power promising to end inequality, eradicate violence, and strengthen democracy. He says the current legal system only serves the country’s elites, and judicial reform is key to cutting out corruption and laying the groundwork for the incoming president, a close ally, to continue his vision for Mexico’s transformation.

But many see this as a political play by the outgoing president.

“This is personal revenge against the justices of the Supreme Court,” says Emiliano Polo, a Mexican lawyer and associate at the Mexican Council on Foreign Relations. Sitting justices have blocked the president’s past attempts to change the Constitution, including overturning legislation that would have put the civilian-run National Guard under the purview of the military and that would have changed how public servants use government advertising in electoral races.

The judicial reform is all but guaranteed to pass. In the new legislative term, which begins next week, the ruling party will have a supermajority in the lower house and be just a few votes shy of the same control in the Senate. The ruling party “already has the executive branch, already controls Congress. The last man standing was the judiciary,” says Mr. Polo.

Why does the U.S. care so much?

Proponents say the proposed judicial reform will fix a system that notoriously fails the public. But critics say it will weaken a key check on presidential power and make the courts more vulnerable to the influence of organized crime, as candidates for judgeships could become beholden to donors.

They also worry that inexperienced judges could reach the bench through political favors rather than on merit. As it is now, it can take 25 to 30 years to become a federal judge, says Mr. Polo. “The requirements to become a federal judge in Mexico are extremely, extremely hard.”

The judicial reform proposal could have the most immediate effect on international investment, however. Trade requires “legal certainty, judicial transparency, and clarity,” said the American Chamber of Commerce of Mexico in an Aug. 26 statement, warning that it sees these elements at risk in the proposed reform.

U.S. Ambassador Ken Salazar called the reform a threat to Mexican democracy and said it would expose the judicial system to the influence of powerful cartels. His comments, and similar criticisms made by the Canadian ambassador to Mexico, led to backlash this week, when Mr. López Obrador said he was pausing relations with both embassies. “They have to learn to respect the sovereignty of Mexico,” he said at his daily news conference Aug. 27.

The U.S. and Mexico are each other’s biggest trading partners, and the reform may violate terms of the North American trade agreement known as the USMCA, formerly NAFTA, says Yussef Nuñez, an analyst at EMPRA, a Mexican political risk firm. The reform “is going to put more stress on bilateral and regional dynamics.”

But doesn’t the justice system need reform?

Absolutely. One figure alone underscores that: Impunity for violent crime is nearly 95% in Mexico. Also, police aren’t well trained in investigating crimes, and the judicial system tends to presume guilt, not innocence. It’s common for people charged with crimes to serve months – even years – in detention before having their cases heard.

The president is leaving office with historically high approval ratings – around 70% – and Dr. Sheinbaum won the top office with a record number of votes. According to government-commissioned surveys carried out by private companies earlier this summer, the public stands behind the reform.

But critics, among them many judges and law students, have gone on strike in recent days to protest it.

“We need an independent judiciary, staffed by people with solid preparation,” said Norma Lucía Piña Hernández, the current head of Mexico’s Supreme Court, at an international conference on judicial independence this month. The reform could “delay justice” for Mexicans.

These critics worry that Mexico may be joining the ranks of other countries in Latin America, like El Salvador, where a popular president has undercut democracy with broad public support. El Salvador has some of the highest levels of satisfaction with democracy in the region, despite its president repeatedly chipping away at independent institutions and concentrating power in the executive.

Mexico is a relatively young democracy, making its judiciary an independent institution from the executive only in the mid-1990s, as it emerged from one-party rule and joined NAFTA.

But democracy hasn’t been a panacea. “Democracy has this whole hype that it will improve everything, but it is also associated with neoliberal policies that have exacerbated inequalities,” says Mr. Nuñez.

“López Obrador was the first to directly talk to vulnerable social classes and recognize them,” he says. “His social programs have made a difference for [them]. ... They’d prefer to have his government’s aid over an autonomous judicial power.”

Podcast

‘Five feet from the president’: Watching history unfold as the press pool reporter

Working in the presence of a U.S. president, with responsibility for faithfully recording every wrinkle on behalf of the collective media, can be harried. It can also be pretty heady. The Monitor’s pool reporters wouldn’t trade it for anything.

Traveling with the U.S. president as a member of the rotating press pool may not be as glamorous as it seems.

There’s the long hours, the waiting, the rush to get pool reports out to the rest of the White House press corps as news happens – no guessing, no speculating, no assuming.

“The point about doing pool is that you have to pay super close attention because at any moment it could be extraordinarily interesting, if not historic,” says the Monitor’s White House correspondent, Linda Feldmann, on our “Why We Wrote This” podcast.

Both Linda and Monitor colleague Sophie Hills do it all with thumbs on a cellphone. Pool duty is, in a sense, a second gig. It has a culture and rules of its own. But the value of those hours observing presidents close up pays dividends.

“It just gives you a well of both hard information and impressions that inform your reporting in an invaluable way going forward,” Linda adds. “There’s nothing like it.” – Gail Russell Chaddock and Jingnan Peng

Scenes From the Press Pool

Difference-maker

For this affordable-housing advocate in Ontario, tiny homes are where the heart is

Much of Canada’s homeless population lives in encampments. Thanks to Nadine Green, some are finding community in villages made of tiny houses, where they can have their own homes.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Nadine Green’s technical title might be site coordinator, but to most, she’s known as “Mom.” The word is scribbled on the door of her home in the community called A Better Tent City.

The prefab village is a project to try to address homelessness on streets and in shelters and encampments – a hot-button political issue in Canada – by creating tiny communities that residents can consider their own. When it opened in 2020 here in Kitchener, some 70 miles west of Toronto, it was the first of its kind in Canada, but it has since inspired similar projects across the country. Its leaders have been contacted by dozens of groups interested in replicating the model.

“We always knew it was going to work,” Ms. Green says.

Amid an affordable-housing crisis, homelessness is a serious concern in Canada. The country faces one of the biggest gaps for developed countries between home prices and income levels. In cities, tent encampments have cropped up and polarized communities, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic. One report says that 20% to 25% of homeless people live in encampments today.

Tiny homes are seen as one solution.

For this affordable-housing advocate in Ontario, tiny homes are where the heart is

When Nadine Green walks the pathway of tiny homes erected in two rows on a small patch of grass at the outskirts of this city, everyone seems to have something to ask or tell her.

For this community of formerly homeless people now each living in their own little house – really, a garden shed with a lockable door – Ms. Green helps with accessing services and resolving disputes. But mostly people just want to chat, and more interactions than not end in a hug. After all, her technical title might be site coordinator, but to most, she’s known as “Mom.” The word is scribbled on the door of her own home in the community.

This prefab village is A Better Tent City, a project to try to address homelessness on streets and in shelters and encampments – a hot-button political issue in Canada – by creating tiny communities that residents can consider their own. When it opened in 2020 here in Kitchener, some 70 miles west of Toronto, it was the first of its kind in Canada, but it has since inspired similar projects across the country. Its leaders have been contacted by dozens of groups interested in replicating the model.

But for Ms. Green, who lives in the community as part of her duties as site coordinator, success was never in doubt. “We always knew it was going to work,” she says – because it was her experience running a similar community in a convenience store she used to own that inspired the model in the first place.

“She took action”

Amid an affordable-housing crisis, homelessness is a serious concern in Canada. The country faces one of the biggest gaps for developed countries between home prices and income levels. In cities, tent encampments have cropped up and polarized communities, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic. One report says that 20% to 25% of homeless people live in encampments today.

Tiny homes are seen as one solution.

Ms. Green didn’t have the land or the funds to found A Better Tent City, but it was her support of the homeless community of Kitchener that laid the foundation of the project.

Ms. Green, who in her teens immigrated to Canada from Jamaica with her mother, always wanted to run a convenience store – the kind of establishment back home where shoppers were not customers but community. Those without cash could run a tab and pay what they owed when their paychecks arrived.

When she opened a store a decade ago in the center of Kitchener, it was right where a homeless population had congregated. Shopkeepers warned her about what they called a nuisance. She opened her doors instead, giving the homeless community free apples and bread, and a place to warm up.

More kept coming, and then some began staying the night. At its peak, the convenience store housed up to 40 people on any given night. Some slept in Ms. Green’s back office, or under a pool table in the store. Sometimes she slept there too, happily.

In January 2020, her convenience store was evicted; she didn’t have the right license to run it as a shelter. But she had caught the attention of a local entrepreneur with ties to the city.

Ron Doyle, who has since died, envisioned creating a village for those without homes – a place where they could live on their own terms – and first offered space in a conference center that was struggling amid the pandemic. He asked Ms. Green to run it and to find the residents to populate it.

Today, A Better Tent City comprises 42 homes. The nonprofit, run with grants and donations and a steady stream of volunteers, includes communal bathrooms, a kitchen, a lounge, and laundry rooms.

Matthew Robb, who goes by the name Dragon, wears the keys to his house around his neck. As a resident here, he takes part in cleaning the showers and helps with nighttime security, and in turn feels part of something bigger. “[When] you’re being judged, shunned by [society],” he says, “actually being part of a community, you feel so much better.”

Dan Bednis, chair of the board of the Hamilton Alliance for Tiny Shelters, says Ms. Green has been critical to inspiring groups like his. “She was appalled at the stigma faced by the unhoused, and she took action as a concerned citizen. Instead of talking about it, she did something about it,” he says. “She’s in my book like an angel. She’s our Mother Teresa.”

“I don’t know where I’d be without her,” says Mike Tughan, who once lived at Ms. Green’s convenience store.

Combating isolation

It’s not that all is perfect in this humming community, says Jeff Willmer, Kitchener’s former chief administrative officer who sits on the board of A Better Tent City. Drugs continue to pose one of the greatest challenges, he says.

But small signs of success abound, such as residents decorating their front entrances and making home improvements. And the way they measure success has slowly evolved too, he says.

While they still hold the ideal of housing for all, they have also learned lessons about what a successful community is, he explains. Providing the privacy of a home organized around communal space has been a model that combats isolation. “I think we can learn something from this about how we design supportive housing,” Mr. Willmer says. “So maybe it needs to look more like a lodging house and less like an apartment.”

As he’s talking, the laundry machine in the common space is whirring. A volunteer cook pulls out hot cross buns from the oven. Ms. Green steps away often to field calls and queries. When she has a moment, she explains her definition of success.

She describes a text she received the day before, from a grandmother inquiring about her granddaughter, a resident, to make sure she was OK.

“I went right to [the granddaughter] and said, ‘You need to message your grandma.’ ‘Oh, I’ll do it later,’ she said. And I said, ‘Do it right now.’”

The grandmother wrote Ms. Green back immediately, an effusive expression of gratitude just to know her family member was alive. “That is pure love; that is worth more than anything,” Ms. Green says.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Workers of the world, volunteer

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

On this Labor Day weekend, many more Americans may take part in community service than they have in the past. Their generosity reflects a shift in the workplace as employees demand a greater commitment to the public good from the companies they work for. Younger workers in particular seek jobs that create both community and mission.

That trend reflects a global change. A Deloitte survey this year in 44 countries found that 86% of Generation Z and 89% of millennials prefer work that has a positive impact on society. Among American companies, “employee volunteering has soared in the past three years,” according to Benevity, a platform that develops workplace volunteer programs.

All that generosity counters depictions of a world fragmented by political bitterness and conflict. “You can read this morning’s newspaper and find out how much we distrust each other and indeed, you could almost say hate each other,” said Robert Putnam, an American political scientist. And yet, he observed, social connections are the evidence of “trust and reciprocity, togetherness.”

In simple acts of helping strangers this weekend, Americans can join a world of volunteers dissolving hate.

Workers of the world, volunteer

On this Labor Day weekend, many more Americans may take part in community service than they have in the past. Their generosity reflects a shift in the workplace as employees demand a greater commitment to the public good from the companies they work for. Younger workers in particular seek jobs that create both community and mission.

That trend reflects a global change. A Deloitte survey this year in 44 countries found that 86% of Generation Z and 89% of millennials prefer work that has a positive impact on society. Among American companies, “employee volunteering has soared in the past three years,” according to Benevity, a platform that develops workplace volunteer programs.

An increasing demand for careers that go beyond self-interest may have been caused by employee isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting rise in remote work. Many younger workers started their careers on Zoom or in largely empty workplaces. Being generous with their time and talents is a way to find common purpose. And they expect companies to share their altruism.

Many are. Forty percent of Fortune 500 companies give grants to nonprofit organizations where their employees can volunteer, according to Double the Donation, which tracks corporate philanthropy. Roughly 60% give their employees paid time off to volunteer. A survey by Benevity found that 80% of companies seek or create opportunities for their employees to engage in “volunteer acts of kindness.”

The rapid growth of employee volunteer activities reverses a downward trend in volunteerism measured by the U.S. Census Bureau over the past decade. According to the latest Gallup index of global generosity, roughly 75% of adults volunteered their time or helped someone they didn’t know last year.

All that generosity counters depictions of a world fragmented by political bitterness and conflict. “You can read this morning’s newspaper and find out how much we distrust each other and indeed, you could almost say hate each other,” said Robert Putnam, an American political scientist, in a recent conversation with The Chronicle of Philanthropy. And yet, he observed, social connections are the evidence of “trust and reciprocity, togetherness.”

In simple acts of helping strangers this weekend, Americans can join a world of volunteers dissolving hate.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Living in the now

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Sandra Balderston

As we recognize our status as God’s beloved children, heartache about the past lifts, and we experience more of the goodness that’s filling every moment.

Living in the now

I had been praying for some time about an ache in my shinbones. During this time I phoned a Christian Science practitioner for metaphysical help with this and other problems. One day I complained to her that I was missing things that had previously been in my life, such as my children, friends, activities, and different places I had lived.

The practitioner pointed out that clinging to the past is human emotionalism that would weigh us down. We live in the now, she said. We don’t negate the good we have previously enjoyed, but we can’t let nostalgia color our present with a sense of loss. She emphasized that man (a term that includes every individual) is the complete and entirely spiritual reflection of God, and that this reflection is going on right now.

Not long afterward, I read that the word “nostalgia” has roots in Greek words that include meanings such as homecoming and pain. At one time it was associated with acute homesickness. When I read that, the constant throbbing in my legs stopped immediately. This prompted me to explore further the concept of homesickness.

The Bible tells us that after their escape from slavery under the Egyptians, the Israelites grew tired of the manna that was sustaining them in their long journey through the wilderness and longed for the relative comforts of their time in Egypt: “We remember the fish, which we did eat in Egypt freely; the cucumbers, and the melons, and the leeks, and the onions, and the garlick: but now our soul is dried away: there is nothing at all, beside this manna, before our eyes” (Numbers 11:5, 6).

A Bible website called The King’s English says of that passage, “In the wilderness years the Israelites would often look back with rose-tinted glasses. ... They looked on the past as their green salad days. But now ... they see only desert and scarcity.”

This made me ask myself if I was like the Israelites, homesick with longing for my former life. I realized that my reminiscing and yearning for what was past had blinded me to God’s abundant good in the present, and that this had been detrimental to my health and well-being.

Then I turned to my hymnal and opened to a hymn that begins, “Pilgrim on earth, home and heaven are within thee” (P. M., “Christian Science Hymnal,” No. 278). As soon as I read that line, I was comforted and knew that I was in my right place, right now, and that God was with me.

Another hymn, by John Greenleaf Whittier, includes these lines: “For all of good the past hath had / Remains to make our own time glad” (Hymnal, No. 238). We can never be separated from good, because, as Christ Jesus taught, we are in the kingdom of heaven, now and forever.

This experience took place several years ago, and I’ve had no pain in my legs since then. But more important, the restless spirit I had for so long is gone. I’m happily settled in my community and no longer think that the grass is greener somewhere else. I visit family members and communicate with them regularly. I also have a fresh sense of purpose in my practice of Christian Science.

If we’re getting caught up in living in the past or always anticipating and pushing toward the future, we can hold to the spiritual truth that our reflection of God, Spirit, is immediate, at this very moment, and includes no yesterdays or tomorrows. Reflection is now – and because God is infinitely good and gracious, we can rest assured that we can’t miss out on anything good and that our needs will always be met.

Adapted from an article published in the Feb. 20, 2023, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

All a blur

A look ahead

Thank you for coming along with us this week. Next week begins with the Labor Day holiday in the United States, so there will be no Daily on Monday. But Tuesday, we’ll offer the compelling story of how the Chinese threat is reshaping Taiwan’s sense of identity, as well as a portrait from a campaign bus ride with Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris.