- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- With Russia targeting Ukraine’s power grid, ‘everyone is an electrician now’

- Today’s news briefs

- Is a Venezuelan gang growing in the US? Colorado feels the threat.

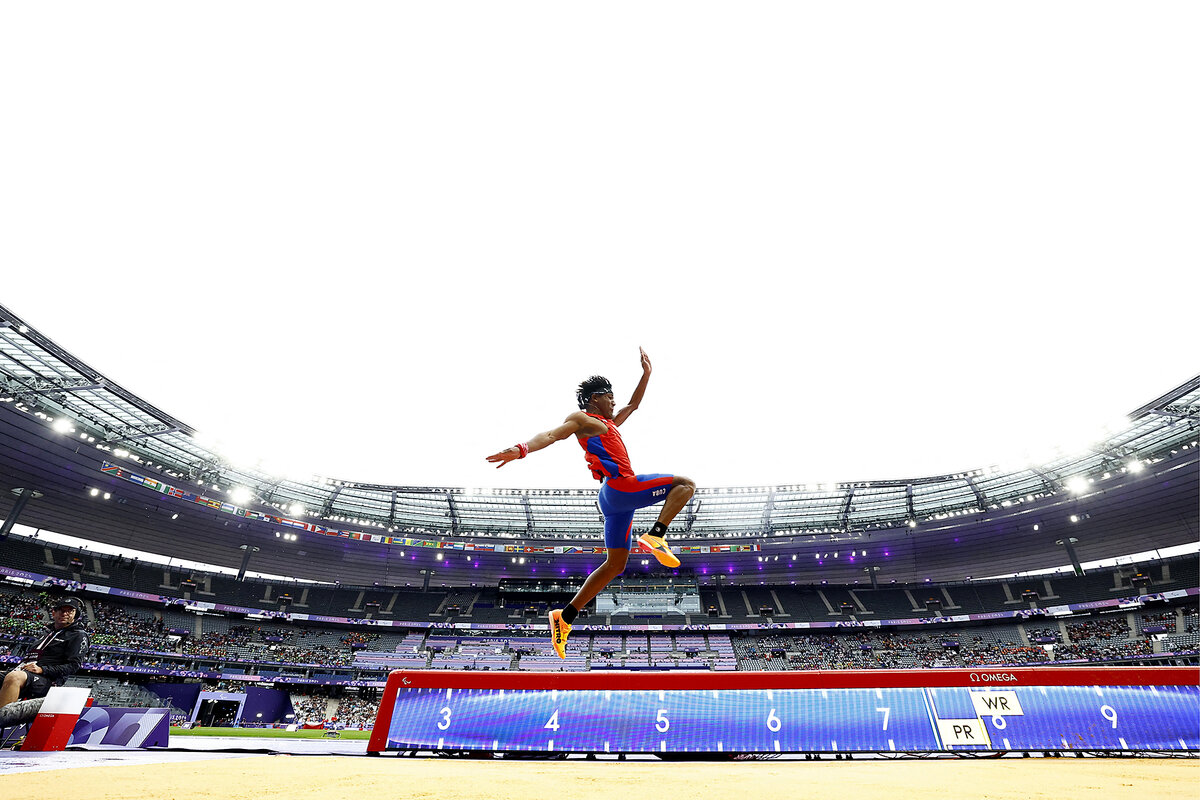

- Paralympic stars shrug off ‘superhero’ label. They’re athletes.

- Asian American history can be scarce in schools. States are trying to change that.

- A Colorado market rescues food to feed the hungry

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The remarkable power of the Paralympics

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

I always chuckle at the flood of pre-Olympics stories about how everything is going wrong and locals are angry. Then the Games start, and something else takes over. Joy and awe.

Today’s story by Colette Davidson adds a poignant twist. In Paris, that shift has also led to something deeper – a realization that the Paralympics are not about disability, but about extraordinary ability. We know that the Olympics can lift spirits. As Colette shows, they can also change minds.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

With Russia targeting Ukraine’s power grid, ‘everyone is an electrician now’

Ukraine’s power grid is a prime target of Russian missiles and drones. And Ukrainians, from individual families to the officials in charge of keeping the lights on, are finding new ways to cope.

For Ukraine, keeping the lights on is a key war aim. Many of Russia’s most recent missile and drone attacks – conducted in apparent retaliation for Ukraine’s incursion into Russia’s Kursk region – have focused on degrading Ukraine’s energy and civilian infrastructure.

A barrage of 100 missiles and 100 drones August 26, for example, targeted electricity distribution substations across the country. In June, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said Russia’s spring targeting of Ukraine’s grid had already destroyed half the country’s power generation capacity – a rate of destruction that continues to far outstrip Ukraine’s ability to make repairs.

Russia’s “goal is to make life as difficult as possible,” says Oleksii Vishniakov, chief of the Balakliia Department of District Energy Networks. He and his team are racing to repair damaged infrastructure across his district – when they have access to its 560 miles of high-voltage lines. The ground near many sections was mined by Russian forces before they retreated in 2022, he says, and demining teams continue to work – and take casualties.

“I consider it some kind of front line here,” Mr. Vishniakov says. “Those who work here overcome their discomfort, because they understand it is important to keep working, to keep the electricity on.”

With Russia targeting Ukraine’s power grid, ‘everyone is an electrician now’

Ukrainian welder Serhii Krasnokutskyi smiles as he points out the hooks already screwed into the frame of a southeast-facing window in his sixth-floor apartment.

That is where his small fold-up solar panel will hang – to absorb the most sunlight – if Russia’s sustained bombardment of Ukraine’s electricity infrastructure catches up with him.

But he and his mother, Antonina Krasnokutska, have been lucky: Their residential building in the eastern Ukrainian town of Balakliia sits along an electrical line deemed to be of critical importance.

So even as most Ukrainians have been experiencing rolling blackouts – due to systematic Russian missile and drone attacks that have destroyed some 50% of Ukraine’s power-generating capacity – the mother and son have only recently started to lose power, too.

“I think the situation will only get worse; Russia has a lot of missiles,” says Mr. Krasnokutskyi. “Everything is related to electricity. … Even the air-raid sirens don’t work without it.”

Indeed, for Ukraine, keeping the lights on is a key war aim. And the accruing damage to Ukraine’s grid and the challenge it is presenting to the country is having political reverberations in President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s government.

The head of Ukraine’s state electricity company Ukrenergo, Volodymyr Kudrytsky, was fired Monday, ostensibly for failing to ensure the sufficient defense of key installations – though media reports suggested political moves, even as a broad Cabinet shake-up got underway.

Many of Russia’s most recent waves of missile and drone attacks – conducted in apparent retaliation for Ukraine’s month-old incursion into Russia’s Kursk region – have focused on degrading Ukraine’s energy and civilian infrastructure.

A barrage of 100 missiles and 100 drones August 26, for example, which targeted electricity distribution substations across the country, required the imposition of emergency power outages “to protect the system,” said Maxim Timchenko, head of DTEK Group, the largest private investor in Ukraine’s energy sector.

“Ukraine’s Armed forces are actively engaged in defending DTEK power stations from incoming missiles,” he posted on the social platform X. Ukrainian officials have pleaded with Western allies for more air defense systems to minimize the impact of such attacks.

In June, President Zelenskyy said Russia’s spring targeting of Ukraine’s mammoth power stations and transmission capacity had already destroyed half the country’s power generation capacity – a strategic rate of destruction that continues to far outstrip Ukraine’s ability to make repairs.

A spring report by the Kyiv School of Economics estimated that Russia had destroyed more than $16 billion worth of energy infrastructure, including two key thermal power plants, and “critical damage of over 80%” to half a dozen others. The report put the cost to “build back better” at $50 billion.

“It’s just fear, sowing fear. … The [Russian] goal is to make life as difficult as possible,” says Oleksii Vishniakov, chief of the Balakliia Department of District Energy Networks.

“I consider it some kind of front line here,” says the no-nonsense, graying veteran of the electrical grid. “Those who work here overcome their discomfort, because they understand it is important to keep working, to keep the electricity on.”

Mr. Vishniakov and his team are racing to repair damaged electricity infrastructure across this district – when they have access to its 900 kilometers (560 miles) of high-voltage lines. The ground of some 530 kilometers of the lines was mined by invading Russian forces before they retreated in 2022, he says, and demining teams continue to work – and take casualties.

So far his team has replaced more than 325 electricity poles with new ones provided by the U.S. Agency for International Development – the new pole digger also comes from USAID – and deployed 160 U.S.-given electrical transmission units and miles of high-voltage cable.

Yet the schedule for electricity “depends on what in Moscow and the Kremlin they decide to hit today,” says Mr. Vishniakov. “As soon as they target something important again, that’s it, we have no electricity and cannot put together a predictable schedule. … Now we are living with the understanding that the situation can change at any moment.”

While Balakliia electricity is usually off just four hours a day, other areas in Ukraine can have as little as one hour a day.

The situation first changed here when invading Russian troops camped in Mr. Vishniakov’s district offices during their six-month occupation in 2022. They left the control room with its intricate, lit-up grid map destroyed, and the rooms wrecked. “I was crying,” the network chief recalls as he walks through the wreckage of his former office.

More recently, the vast Zmiivska thermal power station down the road was struck on March 22 with 18 missiles, knocking out power to the region.

“What I am doing with my crew, we need to prove that we are worthy of those people who are fighting on the front line, because they are fighting for each meter of our land,” Mr. Vishniakov says.

That front line is moving daily as Russia continues to make incremental advances along Ukraine’s eastern front – with a particular push now toward the city of Pokrovsk. Longer-range attacks with missiles and drones pose dangers to citizens and electrical grids alike.

“If you are between the zero line and 10 kilometers from the front, you must act like you are facing the Russians – something can come anytime,” says Colonel Yuri Povkh, military spokesperson for the Kharkiv region.

Balakliia may be 40 miles from the front line, but like a survivalist in his apartment, Mr. Krasnokutskyi is prepared. He has a number of battery power banks, surge protectors, and even a small generator hidden on his balcony.

When the Monitor first met this mother-and-son pair in September 2022, their electricity had just been restored after six months of Russian occupation.

“Electricity is civilization – it is everything,” Ms. Krasnokutska said back then, as they both marveled at the bulb hanging in their kitchen, which had lit up again for the first time just the day before.

The family got through that winter and the next, but now they echo Ukrainian officials in their worry about the strategic impact of Russia’s current campaign, as another ice-cold winter looms. Like many other Ukrainians, Mr. Krasnokutskyi is these days well-versed in the kilowatt requirements of home appliances – and how much he can provide with his 2.8 kilowatt generator.

“It’s a very common problem,” he says. “Everyone is an electrician now.”

Also doing similar math, but on a much larger scale, are Oleksii Yevsiukov and Viktoriia Varenikova, a husband-wife team who created and run the Avex company in Kharkiv, which produces swimming and fitness wear, and is now completely energy self-sufficient.

With a high-tech mix of solar and thermal power – and with the collected energy stored in a custom-fitted Tesla car battery the size of a closet – the company is providing a model for avoiding city blackouts and brownouts. The battery can hold two days’ worth of power if the solar panels do not produce enough.

Their plan to go green predates the Russian invasion. But the war – and its attendant energy uncertainty – was the catalyst to invest in the solar panels that line the workshop roof, and the piping of the geothermal unit in the basement that taps 70 yards deep into the earth to regulate temperature.

The factory worked for half a year with a diesel generator, but it was noisy, and required fuel and an engineer to keep it running. Fourteen staff now work here, producing some 2,000 high-end items for Ukrainian brands amid piles of material and walls covered with spools of thread in every color.

“We did one year of research before the war, then decided to do it,” says Mr. Yevsiukov, who uses excess power created by the solar panels to charge his electric car. “It is good for us, good for the nation, and for everyone.”

Oleksandr Naselenko supported reporting for this story.

Today’s news briefs

• Ukraine resignations: President Volodymyr Zelenskyy orders a major government reshuffle at a crucial juncture in the war against Russia.

• Grenfell Tower report: A damning report on a deadly London high-rise fire in 2017 says decades of failures by government, regulators, and industry turned Grenfell Tower into a “death trap” where 72 people lost their lives.

• Charges against Hamas leaders: The United States announces criminal charges against Hamas’ top leaders over their roles in planning, supporting, and perpetrating the deadly Oct. 7 attack in southern Israel.

• Biden’s student debt plan: Seven Republican-led states file a lawsuit to challenge President Joe Biden’s administration’s latest student debt forgiveness plan.

• High temperatures: The west coast of the United States is bracing for extreme heat with temperatures in desert towns expected to soar as high as 120 degrees Fahrenheit and Phoenix likely to extend its streak of 100 days over 100 F, forecasters say.

Is a Venezuelan gang growing in the US? Colorado feels the threat.

When dealing with gangs, local officials are tasked with maintaining public safety without fearmongering. In Colorado, that ethos is being tested by the reputed presence of a Venezuelan gang.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

Suspected Venezuelan gang activity around Denver is stirring public concern here in Colorado and across the United States – amplifying election-year questions about effects of unauthorized immigration that reach far beyond America’s southern border.

In recent days, local and federal officials here have increasingly gone on record about what they describe as the reputed presence of the gang, called Tren de Aragua.

As local officials offer conflicting narratives about the gang’s level of activity, police and politicians here are boosting efforts to address security concerns. Low-income residents, often other immigrants themselves, may be experiencing the harshest impacts, not just at the hands of criminals, but also in headlines that can cast doubt on whole neighborhoods or nationalities.

It’s “really rare” for a gang to receive this level of recognition from officials, says David Pyrooz, a gang researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder. While agencies typically avoid giving a gang notoriety, he says, it seemed they had an “obligation because of the outcry” to offer some confirmation.

Is a Venezuelan gang growing in the US? Colorado feels the threat.

Suspected Venezuelan gang activity in the Denver metro area is stirring public concern in Colorado and across the United States – amplifying election-year questions about the impact of unauthorized immigration that reach far beyond the U.S. southern border.

In recent days, local and federal officials here have increasingly gone on record about what they say is presence of the gang, called Tren de Aragua. Meanwhile, current criminal court cases in Denver involve a man who’s been, reportedly, linked to the gang by federal sources. And in the neighboring city of Aurora, a resident’s viral video shows armed individuals in an apartment building before a fatal shooting, which authorities are investigating.

The video footage has heightened allegations of a gang “takeover” of certain apartment buildings, which former President Donald Trump has also begun to claim.

As local officials offer conflicting narratives about the gang’s level of activity, police and politicians here are boosting efforts to address security concerns. Immigrant advocates are also denouncing claims of widespread criminal activity, as rumors outpace ongoing investigations. Low-income residents, including other immigrants, may be experiencing the harshest consequences – not just at the hands of criminals, but also in headlines that have cast doubt on whole neighborhoods and nationalities.

It’s “really rare” for a gang to receive this level of recognition from officials, says David Pyrooz, a gang researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder. While agencies typically avoid giving a gang notoriety, he says, it seemed they had an “obligation because of the outcry” to offer some confirmation.

Is a Venezuelan gang gaining a foothold in Colorado?

Cindy Romero wanted to move out of her Aurora apartment for months.

To her relief, Ms. Romero moved out last week, sharing what would become a viral video with Fox31. Through her doorbell camera, she caught an armed group of men wielding guns outside her door.

She had installed a series of door locks with extra-long screws after an escalation of what she calls “organized criminal behavior,” like a shooting she overheard in August. She can also point to where a bullet pierced her car.

Financial concerns and other logistics kept Ms. Romero rooted until Danielle Jurinsky, an at-large City Council member, helped her move out. Ms. Jurinsky believes the gang is behind the apartment building’s unrest and has called for more transparency around Tren de Aragua, also known as TdA.

She says several police officers have called her with the message “You need to know about this gang.” Even if a fraction of the Venezuelans who’ve arrived to the area in recent years are involved, Ms. Jurinsky says, “that is a large number.”

Ms. Romero, meanwhile, is heartbroken – no matter who’s behind the crimes.

“It’s adding insult to injury to be told it’s part of our imagination,” says Ms. Romero, a U.S. citizen. Police were of no help despite her relentless calls, she adds. “The only outreach we got was when we went to the media.”

Ms. Romero says she personally can’t confirm TdA’s role in her security concerns, which are under investigation. Many social media users sharing her video, however, are quick to draw conclusions about the gang’s involvement.

Immigrant residents rallied Tuesday on Dallas Street, Ms. Romero’s old street, to push back on claims their community is linked to TdA. They showed press their bedbug-bitten arms and rodent traps, saying they are victims more of landlord negligence than of criminals.

“Los buenos somos más,” chanted the crowd in Spanish. “There are more good people among us.”

In August, the city closed another complex. The owner, who could not be reached for comment, claims the shuttered building was overrun by a Venezuelan gang. Displaced residents and some city officials counter that the building was instead closed due to long-term disrepair and neglect.

How is Tren de Aragua entering the U.S.?

Tren de Aragua, whose name means “Aragua Train,” emerged from a prison in the Venezuelan state of Aragua. The Biden administration designated the group as a transnational criminal organization in July, and the U.S. State Department is offering up to $12 million in awards for information leading to the arrest or conviction of TdA leaders.

Last year, the U.S. Border Patrol started reporting apprehensions of unauthorized immigrants it considers affiliated with TdA. Nationwide, there were 41 such TdA apprehensions last fiscal year, with 26 in fiscal year 2024 so far. Individuals linked to separate gangs, such as MS-13 and Paisas, are more frequently apprehended at the border.

Border Patrol encounters reached historic highs under the Biden administration – and more Venezuelans have tried to enter the U.S. as instability grips their country. Some conservatives cite TdA reports as evidence of flawed Biden-Harris border security policies. But the administration blames Republicans for blocking a bipartisan immigration bill and points to a dramatic drop in border crossings in recent months after new asylum restrictions.

A Beat That’s Bigger Than Borders

Hopes, fears, and hard decisions: The stories of would-be immigrants are stories that matter. So, too, are the stories and views of the many other stakeholders in the immigration debate, including U.S. ranchers whose land becomes the first zones of contention. Monitor writer Sarah Matusek is based in Denver, a city that has received thousands of people from South and Central American countries over the past two years. She joined host Clay Collins to talk about reporting a sprawling story with completeness and compassion.

Over the past year, American media have increasingly cited law enforcement reports of suspected TdA activity, from New York to Florida. The U.S., however, isn’t the first country to allege TdA’s presence beyond Venezuela. Its reach has reportedly spanned several countries in South America, with a criminal portfolio including murder, extortion, sexual exploitation, and drug trafficking. The Drug Enforcement Administration is investigating the last of these in Colorado.

“In recent months, our agents – working in collaboration with federal, state, and local partners here in Colorado – have seized multi-kilogram quantities of fentanyl destined for the Denver-Metro area from individuals believed to be members and/or associates of the gang known as Tren de Aragua,” says Jonathan Pullen, special agent in charge of the DEA Rocky Mountain Field Division, in an emailed statement.

The DEA declined to answer additional questions about the gang’s operations and regional scope, citing ongoing investigations. The principal suppliers of illicit fentanyl remain the Mexican Sinaloa and Jalisco cartels, says the agency.

Getting the situation “under control”

Adding to rising regional awareness of potential TdA ties is a federal indictment announced last month in Colorado.

The four defendants, all Venezuelan nationals, face charges related to an armed robbery of a Denver jewelry store in June. A spokesperson for Immigration and Customs Enforcement confirms that all four individuals were encountered by the Border Patrol, along the Texas-Mexico border, on different dates in 2023. All were placed in removal proceedings in immigration court, ICE reports.

One defendant, Jean Franco Torres-Roman, who also faces separate criminal charges in Denver County Court, including for attempted first-degree murder, has reportedly been linked to TdA by a federal agency in Texas. A lawyer for the defendant declined an interview request.

In a rare joint interview last week, the Democratic mayor of Denver and Republican mayor of Aurora sought to soothe hysteria as their cities swept into national news.

“The situation is under control,” Mayor Mike Johnston of Denver told 9News. “There is going to be no widespread gang activity in the city of Denver.”

“It’s a serious incident, but it’s not the entire city,” said Mayor Mike Coffman of Aurora. His local police last month announced a task force focused on “violent crime impacting migrants and other communities.”

Investigating the threat – and protecting victims

There’s “very little data” – at least public and confirmed – on the group in the U.S. so far, says Professor Pyrooz. More research is needed, he says, on questions like, Is the gang formally franchising here, or simply appearing through migration? Are crimes gang-motivated or gang-related, by members acting solo?

Homeland Security Investigations became aware of TdA in Colorado earlier this year, says Jeff Brannigan, who served as the deputy special agent in charge of HSI Denver until this month.

Determining a suspect’s gang affiliation can further investigations. However, “the actual criminal offense is our main focus,” says Mr. Brannigan. Still, TdA’s new federal designation – as a transnational criminal organization – opens up dedicated funding for related investigations.

“It’s often the case that criminal enterprises victimize their own,” says Mr. Brannigan. Within migrant communities, unauthorized immigrants especially can be “more easily victimized,” he says, due to fears around approaching police and being deported.

“If somebody comes to us and has information about criminal activity, we want to collect the information and we want to protect the victims,” regardless of immigration status, says Mr. Brannigan. There are immigration protections available to victims or witnesses of crimes, he adds, including certain visas.

“We have been hearing that there is possible extortion,” says Tony Cancino, president of the Aurora Police Association. “There is a lot of gun violence and robberies.” How suspected TdA affiliates are getting their hands on guns, he says, “is the biggest question around.”

Did Denver’s migrant response aid the gang’s growth?

Also unclear is whether people suspected to be linked to TdA have benefited from Denver’s migrant response, including temporary shelter and other services.

The city’s migrant resources have cost around $74 million, says Jon Ewing, spokesperson for the Denver newcomer program. He also says the city does not give out names of individuals served due to privacy concerns.

“If anyone’s benefiting, it’s TdA, because you can’t buy [media] exposure like this,” says Mr. Ewing. He also worries about migrants here being “feared as the other.” The city recently found anti-immigrant and racist signs installed along a busy street.

Mr. Ewing also rejects claims that Denver’s spending on migrants has attracted gang violence. Had the city not offered that aid, he adds, “we would have thousands of women and children living on our streets.”

In recent days, law enforcement have announced a steady drip of TdA developments, such as news that broke Tuesday of arrests of four people in Arapahoe County, which includes Aurora. Meanwhile, the national scrutiny isn’t lost on local police.

“We’re working really hard,” says Mr. Cancino of the union. “We’re tired.”

“Us who are innocent”

Coromoto, a Venezuelan asylum-seeker who wanted to use her middle name for fear of reprisals, is also tired. She sits on the edge of a hotel bed in Aurora, a few miles from her home on Nome Street that the city shuttered last month. She says her brother was killed back in Venezuela while protesting the repressive government.

“There are a lot of us who want to move forward in life, and because of bad people, it’s us who are innocent who are going to pay,” says Coromoto. Here, she says, “I am ashamed to say that I’m from Venezuela.”

That evening, the Aurora Police Department posted news on social media about a Venezuelan suspect it has connected to an aggravated assault and shooting at her former residence. Aurora police now allege he is a “documented member” of TdA.

Another woman, whose middle name is Jackelin, enters the room with a baby held close. Her daughter, 1 month old, wears a pattern of pastel hearts.

Jackelin says her husband, a Venezuelan like her, just lost his job due to Tren de Aragua rumors. It’s unclear where they’ll live next.

For now, Jackelin cradles her daughter on the bed and offers what she can. She lets her baby nurse.

Paralympic stars shrug off ‘superhero’ label. They’re athletes.

It took a while, but the French have warmed up enthusiastically to the Paralympics, buying nearly 2 million tickets. And parents are finding they offer a rare teachable moment when it comes to disability.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

It is not often that the Paralympics, which are currently underway in Paris, attract as much attention and enthusiasm as they are enjoying this week. But the French, who had largely turned their backs on everything to do with the Olympics before the Games began, have changed their minds.

Enthusiasm took some time to build, but sales of tickets to Paralympic events have reached 2 million.

For those who missed the Olympic Games for one reason or another, the Paralympics offer a second chance to experience the Olympic energy. They have also become a teachable moment for parents and educators to talk about living with a disability.

They offer “a way to discuss disability in a more natural, less pedagogical way, while also raising consciousness,” says Cécile Viénot, a Paris-based child psychologist. “Children can teach us something, too, because they’re able to downplay disability without minimizing it.”

Florie Ternoy, a mother of two, says she was glad to have been able to “show our kids … that a disability doesn’t stop you from being successful. We also just wanted to show them what it’s like to go to a big, noisy stadium and cheer along with everyone else.”

Paralympic stars shrug off ‘superhero’ label. They’re athletes.

When Nadia Dadouche’s 7-year-old son asked to go to the Paralympic Games this summer, she was pleasantly surprised. “I thought, this is a great way to live this unique moment and participate in the celebrations,” she says.

Ms. Dadouche had been disappointed by her failure to buy tickets for the Olympic Games; prices were too high. And even though she and her family visited the fan zones around Paris, she felt as if they were missing out on the true Olympic experience.

So she bought tickets for her family to watch wheelchair tennis and blind football. “It has also been a way to show my kids that there are all different kinds of people on Earth and those differences nourish us. There’s definitely an important message to be shared,” she says.

Enthusiasm for the Paralympic Games, which end on Sept. 8, took time to build. But ticket sales exploded after the opening ceremony for the Olympic Games on July 26, which took viewers on a virtual journey through Paris and was widely lauded by the French.

The Paralympics have now sold over 2 million tickets, half of them in the past month. That’s more than the Paralympic Games in Beijing in 2008, and just shy of the amount sold in London in 2012. The Education ministry has also distributed thousands of free tickets to schoolchildren so that they can watch this week’s events.

For those who missed the Olympic Games for one reason or another, the Paralympics offer a second chance to experience the Olympic energy. They have also become a teachable moment for parents and educators to talk about living with a disability.

The Paralympics “are a way to discuss disability in a more natural, less pedagogical way, while also raising consciousness,” says Cécile Viénot, a Paris-based child psychologist. “Children can teach us something, too, because they’re able to downplay disability without minimizing it,” she says.

“Disability becomes part of the scene but not the focus, which should ultimately be to watch sports, support athletes, and experience that Olympic fervor.”

“It’s now or never” to attend the Games

The return of the Olympic Games to Paris, 100 years after the city last played host, has been a source of pride and excitement for most French people, even though many had viewed the impending event with dread. Last March, a poll found that 47% of Parisians planned to leave their city during the Games, citing price hikes, overcrowded streets, and general disinterest.

But the opening ceremony, as well as French Olympic success stories like swimmer Léon Marchand, brought renewed enthusiasm for the Games.

“Many French people regretted leaving Paris during the Olympics and are looking to the Paralympics like, ‘It’s now or never,’” says Éric Monnin, the director of the Centre for Higher Studies and Research into the Olympics and vice president of Olympism at the University of Franche-Comté in Besançon, France. “They want to experience this energy, the celebratory atmosphere.”

And with Paralympics tickets starting at 15 euros ($17), the events are much more affordable than during the Olympics, when tickets could cost hundreds of euros.

Parisian Florie Ternoy says she and her family stayed in the city during the Olympics but never got the chance to see any live events – she couldn’t afford to, and she wasn’t interested in any particular sport. But before long, she found herself getting into the Olympic spirit, turning on the television to show her 3- and 5-year-olds various sporting events, and visiting the France Hospitality House, a fan zone.

Last week, she took her kids to see the Olympic cauldron, still burning at the Tuileries Garden near the Louvre Museum, and went to watch Paralympic track and field at the Stade de France.

“It was important for us to show our kids values like the ability to push yourself to the limits, that a disability doesn’t stop you from being successful,” says Ms. Ternoy. “We also just wanted to show them what it’s like to go to a big, noisy stadium and cheer along with everyone else, to create memories. This experience has helped us Parisians reclaim our city and feel proud to be French.”

Paralympic athletes don’t want to be “superheroes”

Parents aren’t the only ones driving increased interest in the Paralympics. Since the beginning of last year, French teachers have joined a nationwide operation called “My class at the Olympics,” running activities that teach the importance of sports in daily life, accessibility, understanding disability, and inclusion. The French Education ministry also distributed over 190,000 free Paralympics tickets to schoolchildren.

Some “15% of people around the world live with a disability, and anyone can experience disability or mobility problems at any point in their lives,” says Pierre Rabadan, deputy mayor of Paris, in charge of sports, the Olympic Games, and the Paralympics. “The Paralympics have been a great opportunity for teachers to talk to students about disability and hopefully change viewpoints. Seeing the events in person brings it all to life.”

Part of the learning curve for adults, however, has been finding the right words to talk about disability during the course of the Games. Star judoka Teddy Riner found himself in the midst of controversy mid-August when he referred to high-profile Paralympians as “superheroes” and “Avengers.”

Those comments were not well-received by Paralympians such as French wheelchair basketball player Sofyane Mehiaoui, who wrote on his Instagram account, “We are people with disabilities and we want to be considered normal people. We are not superheroes, we are athletes.”

That may not be too hard for the younger generation to grasp. Ms. Dadouche says that her children asked very few questions about the players’ disabilities. “It was interesting to see that they noticed the differences, but that’s it,” she says. “They were just excited to lift their arms in the air and cheer at the top of their lungs.”

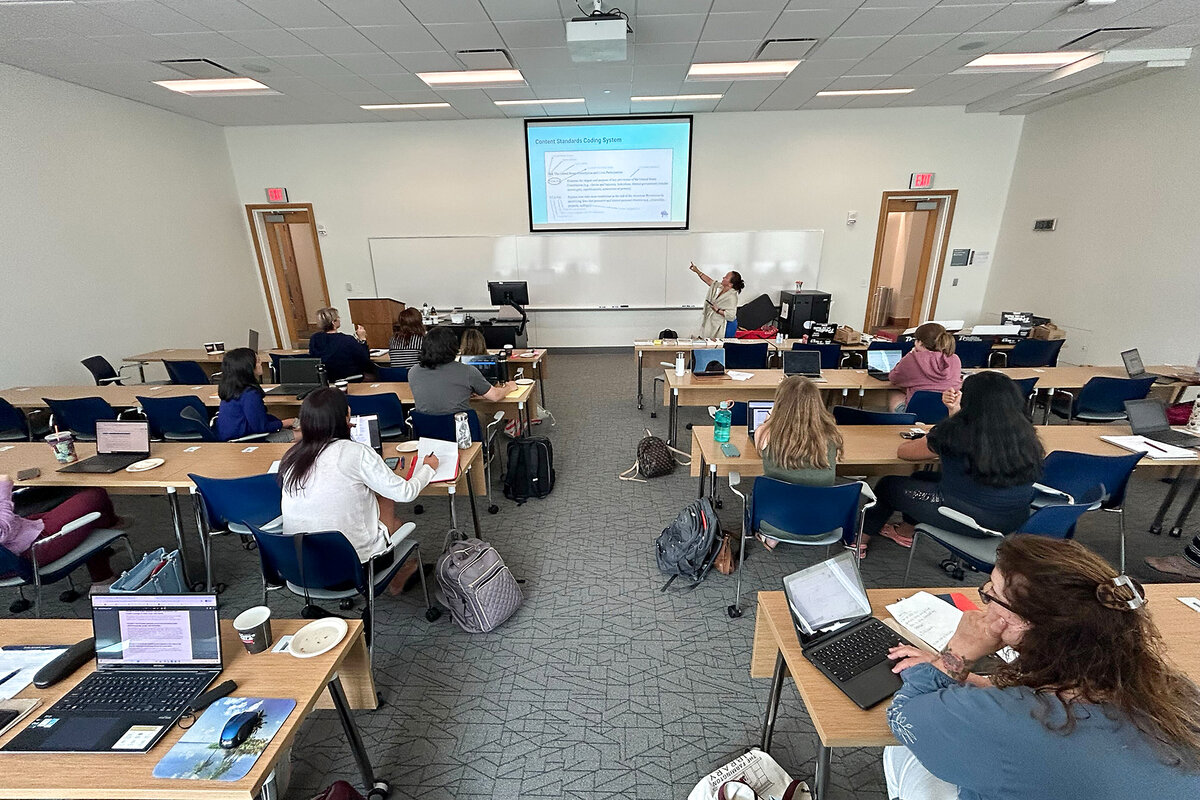

Asian American history can be scarce in schools. States are trying to change that.

What should students in the United States learn about Asian and Asian American culture and history? With hate crimes on the rise, more states are turning to classroom lessons to help foster tolerance and understanding.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

As students return to U.S. classrooms this fall, a quiet revolution is underway. More states have passed laws to teach Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) history in public schools.

In July, Delaware became the latest state to pass such a mandate, joining Connecticut, Illinois, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Florida, and Wisconsin. A rise in hate crimes in the United States has offered urgency to the education mission.

In Connecticut, where the AAPI population has surged by 31% in the past decade, the push to include Asian American history is not just about education – it’s also about being neighborly.

“It’s time we finally learn to understand each other,” says Laura Buffi. The high school teacher was one of a dozen attendees at the University of Connecticut’s Asian and Asian American Studies Curriculum Lab for K-12 teachers in July, the first of its kind in the state.

In the coming year, she hopes to deepen her ties with local AAPI community organizations by organizing field trips and inviting more speakers into her classroom.

“This is what we do,” she says. “We are here to help our students grow.”

Asian American history can be scarce in schools. States are trying to change that.

At a night market in West Hartford, the smells of Vietnamese street food waft through the air, drawing the community into the open. Families descend on the cultural hub, eating together around folding tables with plastic chairs.

Laura Buffi had never attended the bazaar, but plans to bring her high school students back for a field trip. It’s the first night of the University of Connecticut’s Asian and Asian American Studies Curriculum Lab for K-12 teachers, and food is making it simpler to bridge cultural divides.

“It’s time we finally learn to understand each other,” says Ms. Buffi, one of a dozen attendees at the lab held in July, the first of its kind in the state.

As students return to classrooms in the United States, a quiet revolution is underway. More states nationwide have passed laws to teach Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) history in public schools. In July, Delaware became the latest state to pass such a mandate, joining Connecticut, Illinois, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Florida, and Wisconsin.

In Connecticut, where the AAPI population has surged by more than 31% in the past decade, the push to include Asian American history is not just about education – it’s also about being neighborly.

“These changes bring us all together to create and foster more understanding,” says Swaranjit Singh Khalsa a Norwich, Connecticut, councilman who contributed to the passage of his state’s mandate. “The curriculum is not only going to educate our kids but our teachers, our professors, and our parents. So I think we are creating a much more educated society. It’s not just limited to schools.”

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders make up one of the fastest-growing populations in the U.S. Yet their longstanding history in America is largely omitted from the classroom, says Jason Chang, director of the Asian and Asian American Studies Institute at the University of Connecticut and a co-founder of the state’s first Make Us Visible chapter.

His department at the university organized the July curriculum lab, where teachers connected with community leaders and representatives, who trained the teachers on their history, culture, and misconceptions.

“The goal was to give teachers more first hand experience and give some visibility for communities that are underrepresented,” says Mr. Chang. “We wanted teachers to ground the inquiries that they’re bringing into the classroom with experience beyond their formal education.”

Some 18 states had no content on Asians in their K-12 history curriculum standards, a national study published in 2022 found.

When textbooks did include parts of AAPI history, according to the study, by Kennesaw State University Professor Sohyun An, it was mainly about the U.S. internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, or the Chinese Exclusion Act in the 19th century. Yet 22 million Asian Americans trace their roots to more than 20 countries, according to Pew Research Center.

“It’s sad enough that our Asian students don’t have teachers or staff members who look like them. The texts we use don’t even mention them,” says Regina Gatmaitan, one of the few Filipino teachers in her district in Manchester, Connecticut, and a participant in the curriculum lab.

At least students’ learning materials can reflect their stories and cultures, she explains. “We need to teach Asian American history and stories because they’re vital,” she adds. Not doing so is “a disservice to everyone – not just the Asian community, but all communities.”

How have hate crimes influenced what’s taught in schools?

A rise in hate crimes has offered urgency to the education mission. In 2021, anti-Asian hate crimes increased by 339% over the previous year, according to the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism. Nearly 11,000 incidents were self-reported, mostly by women, to the organization Stop AAPI Hate between 2020 and 2022.

Nearly 1 in 3 Asian Americans reported that they had been called a racial or ethnic slur in the prior year in The Asian American Foundation’s annual Social Tracking of Asian Americans in the United States Index, released in May. Nearly 3 in 10 Asian Americans reported they were verbally harassed or abused during the previous 12 months because of their race, ethnicity, or religion.

As incidents have increased, more states have begun mandating that Asian American history be taught in kindergarten through 12th grade. In 2021, Illinois became the very first state with the Teaching Equitable Asian American Community History Act. After Gov. J.B. Pritzker signed it into law, coalitions, such as Make Us Visible Connecticut and Make Us Visible New Jersey, successfully launched campaigns pushing for legislation in their states.

Educators and advocates say the current teaching mandates are underfunded. In Rhode Island, the law outlined a September 2023 rollout, “however, it provided no funding for the curriculum and left school districts to fend for themselves,” says Jeannie Salomon, founder and director of the Cultural Society for Entrepreneurship, Bilingualism, Resources and Inspirations, which is leading Rhode Island’s local efforts to teach AAPI history.

The University of Connecticut’s Asian and Asian American Studies Institute partnered with The Asian American Foundation to develop a state model curriculum for their state’s implementation of AAPI history in 2025.

“Foundations cannot do this work in perpetuity,” says the foundation’s education officer Terry Park. “We need federal and state governments to commit the necessary funding and other forms of support to ensure these mandates are fully implemented.”

New lessons for a new school year

As schools reopen, teachers say that connecting students with the AAPI community should be woven into subjects other than history and extend beyond the classroom.

Ms. Gatmaitan will be teaching sixth grade social studies and life sciences this fall. She plans to connect her lessons to the contributions of AAPI scientists. “I’m looking forward to seeing young people realize that their peers come from a rich heritage and that we can celebrate that together,” she says.

In the past, after hearing from parents that their children had never had a teacher who looked like them, Ms. Gatmaitan started bringing in fairy tales from Asian perspectives for her students in third grade – like Cinderella’s rags-to-riches story, but told through the lens of Hmong, Chinese, or Korean families.

Ms. Buffi hopes to deepen her ties with local AAPI community groups by planning field trips to cultural centers, such as a Sikh art gallery, and inviting more speakers into her classroom.

“This is what we do,” she says. “We are here to help our students grow.”

Difference-maker

A Colorado market rescues food to feed the hungry

The United States is the biggest food waster. The founder of Vindeket Foods finds a second life for items that stores, farms, and restaurants sometimes discard.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Caitlin Babcock Staff writer

Shoppers at Vindeket Foods, a food rescue operation in Fort Collins, Colorado, pile cardboard boxes full of bread, milk, and produce. Not all of the goods are perfect – here and there is a bruised apple, or a container of yogurt past its prime yet still safe to eat. The food is free, though some shoppers make monetary donations to help support the market.

Vindeket has grown from a garage grocery store in 2017 to a thriving nonprofit that, according to founder Nathan Shaw’s calculations, served 120,000 people last year. Unlike many food banks, Vindeket accepts only food and household supplies that otherwise would have been thrown out.

One room at Vindeket is filled with boxes of bananas. “Bananas have a very short shelf life because once they start to ripen, they go downhill very fast,” Mr. Shaw says, holding up a bunch that’s far from bright yellow. But even when the fruit is brown, as he explains to shoppers, it can be used in banana bread, or can be frozen and put into smoothies.

“Ultimately,” he says, “our mission is to change how we as people look at food.”

A Colorado market rescues food to feed the hungry

If it weren’t for Nathan Shaw, a lot of his community members’ dinners would be sitting in a landfill.

Instead, shoppers at Vindeket Foods, Mr. Shaw’s food rescue operation in Fort Collins, Colorado, are piling cardboard boxes full of bread, milk, and produce. Not all of the goods are perfect – here and there is a bruised apple, or a container of yogurt past its prime yet still safe to eat. The food is free, though some shoppers make monetary donations to help support the market.

Vindeket has grown from a garage grocery store in 2017 to a thriving nonprofit that, according to Mr. Shaw’s calculations, served 120,000 people last year. Unlike many food banks, Vindeket accepts only food and household supplies that otherwise would have been thrown out.

One room at Vindeket is filled with boxes of bananas. “Bananas have a very short shelf life because once they start to ripen, they go downhill very fast,” Mr. Shaw says, holding up a bunch that’s far from bright yellow. But even when the fruit is brown, as he explains to shoppers, it can be used in banana bread, or can be frozen and put into smoothies. “Ultimately,” he says, “our mission is to change how we as people look at food.”

Educating consumers

If global food waste were a country, it would be the third-largest contributor to global warming. Food waste contributes 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and the United States is the world’s biggest waster. The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that more food reaches landfills and incinerators daily than any other material.

Food waste also affects consumers’ pocketbooks. The average family of four in the U.S. spends $1,500 each year on food that is never eaten. Edward Spang, an associate professor of food science at the University of California, Davis, points out that this waste is occurring even as food costs rise across the country.

“I don’t think people think about the dollar value,” he says.

Vindeket’s efforts are part of a broader trend. According to the EPA, there are growing efforts across the country to prevent food waste. The agency has an interactive map currently showing nearly 950,000 sources of excess food, including correctional and health care facilities, and about 6,500 potential recipients of that food, including food banks.

Officials and some businesses are also taking steps to address food waste. In June, the White House unveiled a national strategy to cut U.S. food waste in half by 2030. More than 45 businesses and organizations had already committed to that goal within their operations by 2022, including large companies such as Amazon and Starbucks.

Vindeket appeals to shoppers who are making their own individual efforts to address waste. Josanne Lucas, a high school teacher in Fort Collins, says that in the Caribbean community where she was raised, people were always careful to use everything they had. She has shopped at Vindeket for five years and usually takes home produce – “any unusual, atypical foods that I normally wouldn’t purchase,” she says. One of her favorite finds was callaloo, a leafy green vegetable (sometimes called Caribbean spinach) that’s rarely stocked in U.S. stores.

“Growing up, I would always have either neighbors or family members give us any excess fruits or vegetables that they have, and then we also did the same,” Ms. Lucas says. “I like that aspect of Vindeket.”

Before he was the executive director of Vindeket, Mr. Shaw says, he and some of his friends were “big dumpster divers” out of curiosity. While going through garbage looking for usable food, Mr. Shaw was shocked by how much high-quality food was going to waste. “Some of the nicest things” had been tossed out, he says.

The food at Vindeket needs saving for a variety of reasons. Grocery stores sometimes throw out products that are past their “best by” date stamp, even though they are still safe to eat. Food could have been overstocked or damaged, or was simply not visually appealing.

That’s why, in addition to providing a no-cost market for the community, Mr. Shaw and his staff strive to educate people about food waste through social media, online videos, and community events and classes. He hopes that if people change their standards for what they find acceptable in food, it will prompt stores to keep food on their shelves longer.

Dr. Spang affirms that education is a valuable tool in reducing food waste.

“A lot of consumers don’t know that those date labels are not representative of the moment some food is bad for you,” he says. “It’s just the producer’s best guess of how long they can guarantee quality.”

Community buy-in

Vindeket’s food is donated by grocery stores, restaurants, and farms, which are able to receive tax deductions on the gifts. Some donors are regulars; others are spontaneous.

“It’s so varied, because we’ll have someone hit us up out of nowhere,” Mr. Shaw says. “We’ll hear of a truck on [Interstate 25] that maybe got denied at some distribution center because some of the peppers had a weird speck on them, or maybe the temperature was a little off on some broccoli, or whatever it is. And so they’ll call us.”

Alex Zeidner is one of Vindeket’s regular donors. He owns the nearby Folks Farm & Seed, which he started in 2019 on the land on which he grew up. Folks Farm & Seed has collaborated with Vindeket for about four years and makes a donation most weekends. “I just love to see the stuff get used one way or another,” Mr. Zeidner says. He used to be a Vindeket customer and says the kindness of the staff members he interacted with was his favorite part of shopping there.

“I see the work that they’ve done and how they’ve grown as very inspiring,” he says. “They keep showing up.”

The name Vindeket meshes the words “advocate” and “vindication,” Mr. Shaw says. He sees vindication in this case as righting a wrong, by extending the life of food. “We are advocates of the vindication,” he explains, smiling.

Mr. Shaw points out that about a year ago, an older shopper approached him. “I don’t feel broken when I come here,” the shopper told him.

Vindeket is giving food and, in some cases, people a second chance.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Lifting Lebanon with one arrest

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For months, Lebanon has been in the news mostly for the artillery fire across the border between the country’s militant group Hezbollah and Israel. On Tuesday, a different kind of headline caught global attention, bringing light to Lebanon’s dark circumstances.

Prosecutors arrested the Mediterranean country’s former chief central banker, Riad Salameh, for alleged embezzlement. The move led the Beirut-based newspaper L’Orient Today to ask whether it signaled “the end of impunity in Lebanon.”

Even asking the question is a milestone. Lebanon has been caught in a prolonged political and economic crisis.

Yet when governments falter to such a degree, a single act of accountability can mark a turning point.

“We have opened a new chapter, a very positive development,” says Ali Noureddine, a Lebanese economist.

Civil society organizations have called on citizens to join a “solidarity sit-in with the judiciary” in front of the Beirut Justice Palace on Sept. 5. Drawn by a rare act of accountability, they may help embolden officials to further acts of honesty over impunity.

Lifting Lebanon with one arrest

For months, Lebanon has been in the news mostly for the artillery fire across the border between the country’s militant group Hezbollah and Israel. On Tuesday, a different kind of headline caught global attention, bringing light to Lebanon’s dark circumstances.

Prosecutors arrested the Mediterranean country’s former chief central banker, Riad Salameh, for alleged embezzlement. The move led the Beirut-based newspaper L’Orient Today to ask whether it signaled “the end of impunity in Lebanon.”

Even asking the question is a milestone. Lebanon has been caught in a prolonged political and economic crisis orchestrated, the World Bank has noted, “by the country’s elite that has long captured the state and lived off its [economy].”

Yet when governments falter to such a degree, a single act of accountability can mark a turning point. “We have opened a new chapter, a very positive development,” Ali Noureddine, a Lebanese economist, told The Wall Street Journal.

The apprehension of Mr. Salameh is an example of a failed state trying to right itself. Since an economic collapse in 2019, the people of Lebanon have endured persistent shortages of water, electricity, internet access, and health care. Elections have been repeatedly postponed. More than 130 towns now have no local government. The country ranks near the bottom of global corruption indexes. Levels of public trust, a survey by Arab Barometer published in July found, are among the lowest in the Middle East.

A push for legal reform has offered a cautious counterpoint. Last spring, for example, officials in the justice ministry and Parliament joined forces with the United Nations, the European Union, and civil society organizations to strengthen Lebanon’s judicial institutions. A judiciary that is free, independent, and impartial, one member of Parliament noted at the time, is essential for rebuilding people’s trust in the State.

A former Merrill Lynch banker who ran the central bank until last year, Mr. Salameh faces indictments in the United States and at least seven European countries for allegedly running a ring of bankers accused of laundering and embezzling hundreds of millions of dollars. His arrest follows a tug-of-war among public officials, prosecutors, and judges over whether and how to hold him accountable. Skeptics worry his apprehension marks an attempt to avert greater international scrutiny of corruption in Lebanon.

But even the cautious reactions from civil society and fellow bankers show an expectation of integrity. “Any measure taken to expose the rampant corruption established by Riad Salameh in the country is welcome,” Tanal Sabah, president of Lebanese Swiss Bank, told L’Orient Today. “When the judiciary fulfills its duty and role with independence and courage, justice is served,” Ibrahim Kanaan, head of the parliamentary Budget and Finance Committee, wrote on X. The country’s caretaker justice minister, Henri Khoury, said, “The judiciary has spoken, and we respect this decision.”

Civil society organizations have called on citizens to a “solidarity sit-in with the judiciary” in front of the Beirut Justice Palace on Sept. 5. Drawn by a rare act of accountability, they may help embolden officials to further acts of honesty over impunity.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Seeking solutions? Find Truth.

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Tony Lobl

The more we learn of divine Truth, God, as supreme, the more consistently we find the answers and healing we need.

Seeking solutions? Find Truth.

London commuters regularly hear the public service announcement “See it. Say it. Sorted.” This is a message of assurance – if something disturbing is going on, you can call the British Transport Police to come and sort it out.

It occurred to me recently that we might believe that this is also how prayer works. We see that we have a problem. We go to God in prayer. Then we expect God to sort it out for us.

But Christian Science gives us insight into praying from the standpoint that, in God’s view, everything is already “sorted.” This kind of prayer recognizes that our need isn’t to have God fix our problem by turning the experience we seem to be undergoing into a better one; it is instead to yield what we are seeing and are convinced is true to what God, Spirit, knows, which is the spiritual and the only real.

As we do this, we see that we are not mortals at the mercy of conditions beyond our control, but rather citizens of God’s kingdom, completely under God’s control, which never wavers and is 100% benign.

This describes the reality known so vividly to Jesus, who proved it in his remarkable physical healings – which included, on more than one occasion, feeding thousands when resources appeared limited to a few fish and loaves of bread. In each case, the situation seemed far from sorted, yet he showed that it was.

Jesus consistently entertained the Christ view, which perceives the spiritual fact and power of God’s governance. He had a constant, conscious understanding of divine Science, described in Mary Baker Eddy’s “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” as “the understanding by which we enter into the kingdom of Truth on earth and learn that Spirit is infinite and supreme” (p. 281).

In this kingdom, it’s not a set of circumstances that brings us happiness but the joy of knowing our oneness with God – divine Truth – which endures independent of shifting circumstances. It’s not having a rewarding career or being popular that brings fulfillment, but the consciousness of being a spiritual idea of the divine Mind, God, and forever needed for God’s expression of Himself to be complete. And it’s not merely regaining or sustaining health, but gaining “the absolute consciousness of harmony and of nothing else” (Mary Baker Eddy, “Rudimental Divine Science,” p. 11) that brings bliss, peace, and purpose.

The kingdom of Truth is the consciousness of our spiritual identity and everyone else’s – of a flawless goodness that leaves nobody out.

As Jesus’ healing ministry proved, the Science that reveals Truth’s kingdom also brings to light the presence of what we might appear to lack, such as health, provision, or right relationships. These things are certainly needed and welcome, and are more consistent in our experience when they emerge from our spiritual progress.

But we aren’t seeking the kingdom to eat the loaves, so to speak, as Jesus counseled those he sensed were following him for that reason. The meat that never perishes is the spiritual reality that we discern and demonstrate – the eternal Truth, which can never become untrue.

Jesus wasn’t a displaced seeker after the true kingdom; he was at all points anchored in it. But he knew that the rest of us have to shift from focusing on what we seem to need to seeking the purely spiritual and ever-present good that he was so conscious of. He said of that divine goodness, “Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you: for every one that asketh receiveth; and he that seeketh findeth; and to him that knocketh it shall be opened” (Matthew 7:7, 8).

Every time we ask for a clearer understanding of reality, we will receive it; whenever we sincerely seek Truth, we will gain it; and when we knock on the door of God’s kingdom to apprehend, accept, and express its reality and harmony, we’ll find that whatever seemed out of kilter is already sorted.

This seeking and finding involves sitting at the feet of Christ to gain Truth’s ever-fresh inspiration and its insight into itself. Science and Health says, “Spirit imparts the understanding which uplifts consciousness and leads into all truth” (p. 505). As we study the Bible and Mrs. Eddy’s writings and pray, our thoughts open to this divine imparting that lifts us above a limited, material sense of existence to the “consciousness of harmony and nothing else.”

Adapted from an editorial published in the Sept. 2, 2024, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

An ancient river once again finds its own way

A look ahead

Thank you for coming along with us today. We hope you’ll come back tomorrow when Ned Temko looks at a question governments worldwide are wrestling with. What do you do with social media and the titans behind it? Brazil might offer some clues.