- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Fueling Israel-Iran escalation: Dangerous parallel universes

- Today’s news briefs

- Why Georgia’s new election rules have local officials worried

- Vance shows polish, Walz hits him on Jan. 6 in VP debate

- How a husband-and-wife reporting team gets the news out in Ukraine

- Her power in Poland came accidentally. She kept it with stamina – and Facebook.

- Mrs. Tippet’s school of life: The teacher who made me fall in love with writing

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The VP candidates were civil. So what?

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Calls for civility can seem vague and at times naive. In the current political climate, civility can be seen as merely nice to have, or even an impediment to progress.

Today’s Daily shows why none of that is true. Cameron Joseph’s story from Georgia about the distrust of poll workers is poignant and worrisome. A key driver of that loss of faith is incivility.

So when the U.S. vice presidential candidates treat each other with civility, as we discuss in an article and the editorial, it is more than a change of pace. It is a path forward. What the world most needs is not our opinions but our higher natures.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Fueling Israel-Iran escalation: Dangerous parallel universes

A nation’s need to establish deterrence as a guarantor of its security has always risked cycles of escalation with an adversary. As Israel and Iran trade blows, their competing views of the same events are sending tremors through the Middle East.

-

Scott Peterson Staff writer

Iran’s unprecedented ballistic missile barrage targeting much of Israel Tuesday evening generated widely shared imagery that shook Israelis. How Israel chooses to respond, and how Iran reacts, could decide the future of the Middle East.

Iran explained its attack as revenge for a recent surge of Israeli strikes against Iran’s most powerful allies, including the assassination of Hassan Nasrallah, the Lebanese Hezbollah militia chief. It warned of catastrophic consequences if Israel should make the “mistake” of escalating again.

For his part, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Iran had made a “big mistake.”

“Those who attack us, we attack them,” he said in a televised address.

The dueling reactions point to the distinct and dangerous parallel universes that Iran and Israel now inhabit, at a threshold moment that risks spiraling into an uncontrollable succession of retaliatory raids that could spark an all-out war.

In Israel, the government is choosing from a range of options, including attacking Iran’s oil production installations, military targets, and even nuclear production sites.

“There’s a hope that last night would deter Israel, but personally I don’t envision that,” says Hassan Ahmadian, an assistant professor at Tehran University. “The next round might be really more devastating, on both parties.”

Fueling Israel-Iran escalation: Dangerous parallel universes

As Iran unleashed an unprecedented ballistic missile barrage at Israel Tuesday evening, real-time air raid warning maps were crowded with red location spots. The image of the entire country under simultaneous attack – shared repeatedly on social media and in news reports – shook Israelis.

How Israel chooses to respond, and how Iran reacts, could decide the future of the Middle East.

Iran explained its attack as revenge for a recent surge of Israeli strikes against Iran’s most powerful allies, including the assassination Friday in Beirut of Hassan Nasrallah, the Lebanese Hezbollah militia chief. It warned of catastrophic consequences if Israel should make the “mistake” of escalating again with its own use of force.

For his part, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Iran had made a “big mistake.”

“Those who attack us, we attack them,” he said in a televised address to the nation.

The dueling reactions point to the distinct and dangerous parallel universes that Iran and Israel now inhabit, at a threshold moment that risks spiraling into an uncontrollable succession of retaliatory raids that could spark an all-out war.

“The Israelis have upped the ante more than Iranians could bear” with their assault on Hezbollah, says Hassan Ahmadian, an assistant professor of Middle East studies at Tehran University.

“You can sense it in the public, [which] started pushing for something to be done to stop Netanyahu,” says Dr. Ahmadian. “‘We need to do something to stop them.’ ... You could hear it all over the place.”

Iran’s calculation appears to have shifted. Until only a few weeks ago, it had been making clear that it wanted to avoid a regional war. Now Tehran appears to have decided that the price of doing nothing in response to Israel’s recent actions outweighs the heightened risk of triggering a wider war that might draw in the United States.

“There’s a hope that last night would deter Israel, but personally I don’t envision that,” says Dr. Ahmadian. “The next round might be really more devastating, on both parties. The Israelis might do something bold, which then will push the Iranians ... to adopt a more assertive posture. That means a stronger and broader attack.”

In Israel, the government is choosing from a range of options, including attacking Iran’s oil production installations, its military command and control facilities, and even its nuclear production sites. President Joe Biden said Wednesday he would not support any Israeli strike against Iranian nuclear facilities.

Still, Naftali Bennett, a former prime minister, said Israel had the “biggest opportunity in the past 50 years” to reshape the Middle East in its favor, and called for strikes to “destroy” Iran’s nuclear program and energy facilities.

“The tentacles of that octopus are severely wounded – now it’s time to aim for the head,” Mr. Bennett posted on social media.

With Iran’s allies, Hamas and Hezbollah, on the defensive, “This is a unique opportunity,” says Chuck Freilich, former Israeli deputy national security adviser. “The question is ... What can we achieve? If we have the capability to achieve a long-term postponement” of Iran’s nuclear program, “this may be the last good opportunity to try and do something.”

Israel’s next move, suggests Mr. Freilich, should be “to hit them hard, and to deter, but with the goal of not leading to a further escalation.”

That is a delicate balance.

In an apparent effort to fend off an Israeli response to Iran’s Tuesday night missile barrage, Tehran is stepping up its warnings about the potential consequences.

Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian said Israeli air defenses were “more fragile than glass” and that if Israel “makes a mistake again, the next response will be much more devastating.”

Iran’s defense minister, Brig. Gen. Aziz Nasirzadeh, urged Europe to control Israel’s reaction, or “They will face Iran’s response, and the region will enter into a big war.”

And Speaker of Parliament Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf warned that Iran had “devised an unexpected plan to counter any potential madness” from Israel, and advised the United States to “tighten the leash of its rabid dog to prevent it from self-harm.”

Israeli experts brush off such talk.

The lack of casualties and strategic damage resulting from Iran’s missile barrage Tuesday, as in a previous Iranian attack in April, reveals “a certain picture – that this is not a show of Iranian strength but one of strategic weakness,” argues Ambassador Jeremy Issacharoff, former vice director general of Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs who dealt extensively with Iran in his career.

Most of the missiles were neutralized by American and Israeli air defense systems, as Iran targeted three Israeli military bases and the Tel Aviv headquarters of Israel’s Mossad intelligence service. One fatality was reported, a Palestinian in the West Bank reportedly struck by debris from a missile shot down in midair.

Iran can do no more than fire more of the same kinds of missiles that they used on Tuesday, says Mr. Freilich, and “Israel can weather the response.”

Ambassador Issacharoff argues that Israel should “take our time, weigh options, and decide how to go forward,” in a manner that is closely coordinated with Washington. But, he cautions, “You cannot only have a military response to Iran; you need a political response at the end of day.”

The current hostilities between Israel and Iran, says Dr. Ahmadian in Tehran, are “about the escalation dominance that the Israelis are trying to achieve, to then translate it into a balance in their favor. And the Iranians ... are trying to prevent the Israelis from establishing that.”

Meanwhile on Wednesday, Israel deployed more troops in its ground assault on southern Lebanon, designed to destroy Hezbollah tunnels and hideouts so as to make northern Israel safe again for residents who were evacuated a year ago because of Hezbollah rocket fire.

The first report of Israeli soldiers killed in combat – eight in total – were announced just as Rosh Hashana, the Jewish new year, was about to be ushered in Wednesday evening.

Today’s news briefs

• Typhoon approaches Taiwan: Typhoon Krathon brings strong winds and torrential rainfall as it nears Taiwan, leading to the evacuation of thousands from low-lying or mountainous areas.

• Biden to survey Helene damage: President Joe Biden will survey the destruction in the Carolinas on Oct. 2 as floodwaters recede. Vice President Kamala Harris will tour neighboring Georgia.

• Ukraine withdrawal: Ukrainian forces are withdrawing from the front-line town of Vuhledar, located atop a tactically significant hill, after more than two years of battle. It is the latest urban settlement to fall to Russia.

Why Georgia’s new election rules have local officials worried

America has seen how a big nationwide election can come down to relatively few votes in key states. Georgia is ground zero for concerns that partisan officials are making the vote count less trustworthy.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

A fight over election rule changes is playing out in states from North Carolina to Wisconsin to Arizona that could foreshadow an even messier postelection legal brawl.

Former President Donald Trump continues to insist the 2020 election was stolen from him, and he has repeatedly claimed, with no evidence, that Democrats are gearing up to do it again. Republicans have been heavily investing in “election integrity” efforts that they say are aimed at preventing voter fraud. Democrats say those efforts are disenfranchising left-leaning voters, and laying the groundwork to overturn results if things don’t go Mr. Trump’s way.

Georgia is the epicenter of this fight. Trump allies on the state’s election board have pushed through a number of last-minute measures – such as requiring a hand count of ballots – that Democrats and some Republicans say could throw the whole election process into chaos. Even if judges ultimately toss out the new rules, the controversy could give Mr. Trump grist to claim the system was rigged against him.

Local election workers here are training and preparing for Nov. 5 – with the risk of delays and controversies on the line.

Why Georgia’s new election rules have local officials worried

With Election Day looming, three dozen poll workers are gathered in a conference room at the Rockdale County Board of Elections for a crash course in voting rules and procedures. But before they can get to the normal training for running elections in this majority-Black, middle-class community in suburban Atlanta, there’s a new hurdle to sort out.

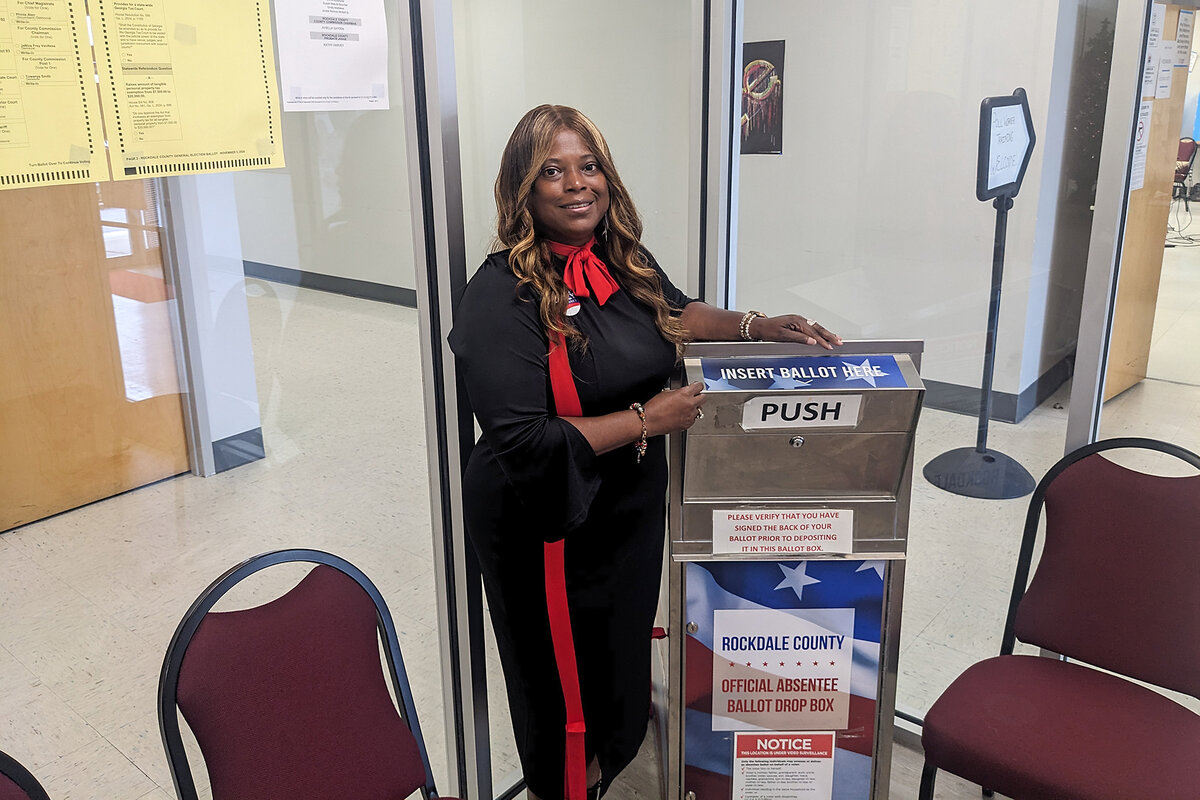

“How many of you have already heard on the news talking about the hand count of ballots?” asks Rockdale County Supervisor of Elections Cynthia Willingham.

Every hand shoots up.

“That’s another task for us to do on Election Day. And we’ve heard where people say it’s going to delay the count and so forth,” she says. “So I have come up with a procedure that I hope will work well, where it still will get you all out of the precinct on time.”

Ms. Willingham, who has been supervising elections in the state for 35 years, had spent the previous day racing to create a mock-up tally form so her workers could learn how to comply with a last-minute rule imposed by the Georgia State Election Board requiring that all ballots cast on Election Day be counted by hand. That means after typically working a 14-hour shift running the polls, these workers, most of whom are senior citizens, will begin the laborious task of individually tallying ballots to try to make sure the total matches the machine count for their precinct. Experts say the process could introduce human error and significantly delay the reporting of results.

It’s one of a number of highly controversial changes recently implemented by the Georgia State Election Board after hard-right activists gained a voting majority in May. Other new rules give local election officials wide leeway to conduct a “reasonable inquiry” into any perceived problems with the voting process, and potentially to toss out votes. Georgia’s Republican attorney general and secretary of state have both warned that the new rules may violate state law. Voting rights groups and Democrats have brought lawsuits to try to block their implementation, several of which are being heard in court this week.

The maneuvering in Georgia is part of a broader fight that’s playing out in key swing states from North Carolina to Wisconsin to Arizona and could foreshadow an even messier post-election legal brawl – especially if the election results are as close as polls suggest. Former President Donald Trump continues to insist the 2020 election was stolen from him, and he has repeatedly claimed, with no evidence, that Democrats are gearing up to do it again. Republicans have been heavily investing in “election integrity” efforts across the country that they say are aimed at preventing voter fraud. Democrats say those efforts are really aimed at disenfranchising left-leaning voters, sowing uncertainty, and laying the groundwork to try to overturn election results if things don’t go Mr. Trump’s way in November.

Georgia, a crucial battleground state that could determine who wins the 2024 presidential election, is the epicenter of this fight. Democrats, along with some longtime Republican officials who refused to help Mr. Trump overturn his 2020 loss in the state, say the new rules imposed by the election board threaten to throw the whole election process into chaos. Even if judges ultimately toss out the new rules, the controversy could give Mr. Trump and his allies grist to claim the system was rigged against him.

“Everything that they’re doing is destroying voter confidence,” Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, the state’s top election official and a Republican, told the Monitor in an interview last week. “It’s just a breeding ground for conspiracy theories.”

The view from one Georgia county

The eleventh-hour changes have brought added stress to local election officials, and could pose a particular hurdle in the parts of Georgia upended by the recent winds and floods of Hurricane Helene.

Ms. Willingham is facing it all with a cheery can-do attitude, insisting that she, her six staff members, and the 175 poll workers will be able to learn every new procedure before early voting begins in the state on Oct. 15.

Still, she worries that a new rule giving partisan election monitors the right to access areas previously restricted to poll workers and officials could expose voters’ personal data and information. And she expresses frustration with how the election board’s majority had dismissed election workers’ concerns on a number of new rules.

“I just wish that the State Election Board would have a little bit more faith in us and what we do,” she says.

A controversial 2021 election reform law passed by Republicans included a provision allowing Georgia citizens to challenge the validity of an unlimited number of voter registrations. GOP activists have seized on it to challenge tens of thousands in the state, forcing understaffed county offices to spend hours slogging through paperwork to see which if any have merit. It’s overwhelmed some offices, especially in Democratic parts of the state where the activists have trained their fire. Another provision hanging over them: If the State Election Board determines county officials are failing to do their jobs properly, the board can take over running that county’s elections.

Election workers face threats

Election officials here, as in many parts of the country, have faced death threats and swatting attempts.

Recently, Ms. Willingham was grocery shopping while wearing her “Ask me how to register to vote” shirt when a man came over and confronted her.

He said “something to me like ‘you’re trying to add more dead people to the voting rolls,’” she says. Remembering that her state-provided de-escalation training had taught her not to engage with hostile people, she extricated herself from the conversation. Since then, she’s stopped wearing the T-shirt in public.

After the incident, “I told my staff, if you’re going out, we can’t walk around in these shirts like we used to,” she says. She plans to have 10 police officers stationed at her office throughout the election. “We can’t live by fear, but you can plan for the unexpected.”

That de-escalation training was part of a broader effort by Mr. Raffensperger’s office to deal with the threats and intimidation that have rained down on nonpartisan election workers since the 2020 election. Two Fulton County workers were forced to flee their homes after Trump allies including Rudy Giuliani falsely accused them of working to rig the election (they later sued Mr. Giuliani for defamation and won a $148 million judgment). Georgia’s new safeguards include an emergency texting line, panic buttons that immediately dial 911, and Narcan, a medication used to reverse opioid overdoses, after someone mailed fentanyl to election officials in Georgia and other states late last year.

Other local election officials are being cautious as well. In Bartow County, a heavily Republican community outside Atlanta, Elections Supervisor Joseph Kirk asks this reporter not to mention where in Georgia he grew up – he doesn’t want his family on anyone’s radar. He’s worked in elections for more than two decades, and says the concern about personal safety is “a whole new thing.”

As the incoming president of the Georgia Association of Voter Registration and Election officials, the nonpartisan group representing local election officials statewide, Mr. Kirk is careful in how he talks about the State Election Board. But he’s clear about his frustration with this year’s last-minute rule changes.

“The rules have been characterized as just common-sense stuff that nobody could possibly have an issue with. And I disagree,” he says. “Elections aren’t as straightforward as some folks might make them out to be.”

The appointee behind new rules

Most of the changes in Georgia’s election rules have been spearheaded by Janice Johnston, a retired OB-GYN and former Fulton County poll worker and poll watcher who became one of the state’s leading right-wing activists in questioning Georgia’s election system after the 2020 election. She was appointed to the State Election Board in 2022 by the Georgia Republican Party (each party gets one representative). The party’s chairman at the time was David Shafer, who currently faces criminal charges stemming from his role organizing a false slate of electors (and serving as one of the false electors) for Mr. Trump in the then-president’s attempt to overturn his 2020 election loss in the state.

Eight different Georgia county officials have voted against certifying their county’s election results in the past two elections, according to a study conducted by the left-leaning ethics watchdog Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Government (CREW), though all were outvoted by the majorities in their counties. All were Republicans; all but one represented Democratic-heavy counties in metro Atlanta. Dr. Johnston has corresponded and closely worked with a number of them, according to a report in Rolling Stone, citing emails obtained by the magazine.

After Dr. Johnston joined the board, she unsuccessfully pushed to investigate Mr. Raffensperger and to end no-excuse absentee voting in the state. But then an establishment-leaning Republican retired and was replaced by a hard-line ally in May, giving Dr. Johnston the power to push through a bevy of new rules.

Dr. Johnston didn’t respond to an interview request for this story. At a late September hearing, where the board passed the new hand-counting rule, she listed other rules she said had been put into place close to an election.

“The hue and cry about how early or how late it is to be adopting these rules, I don’t buy,” she said. “There’s no exception: A good rule is good.”

Former President Trump has taken notice of her efforts. At an August rally in Georgia, he praised Dr. Johnston and her two right-wing allies on the board by name, calling them “pit bulls fighting for honesty, transparency, and victory.” Dr. Johnston, who was at the rally near the front, stood up and waved as Mr. Trump personally thanked her and the crowd cheered.

“Just a simple hand count”

The new rules don’t just threaten to undermine voter trust. They also could land low-level poll workers in the middle of a maelstrom.

Ms. Willingham repeatedly reminds her trainees that they could face public scrutiny and possible subpoenas. She encourages the workers to call her office if anything odd comes up, like a voter walking out with their ballot, and she repeatedly emphasizes double-checking every detail, in case “one of the people that are hand-counting the ballots is called to testify” in court post-election.

The training for the new hand-count rule – requiring that three workers independently count the ballots in separate stacks of 50 – adds nearly an hour to the overall session, extending it well past its scheduled three-and-a-half hours.

“They said ‘this is just a simple hand count,’” Ms. Willingham says about halfway through the exercise, as some in the room laugh wearily. “If they walked through this with us, they would understand. ... But we’re going to roll with it.”

While the workers in the room seem comfortable that they’ll be able to get things right, they aren’t confident that will be true elsewhere in their state – a sign of how much the last-minute scramble could undercut trust in the system.

“My concern is as a citizen in the state of Georgia,” says one poll worker after raising her hand toward the end. “You’re saying this is what you’re doing, because Rockdale is going to do it right. But what about the other 158 counties?”

The rest of the room murmurs in assent.

Vance shows polish, Walz hits him on Jan. 6 in VP debate

JD Vance used the U.S. vice presidential debate to show an empathetic side. Tim Walz called out Mr. Vance for avoiding a question on the 2020 election outcome. Both showed a level of civility now rare in national politics.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

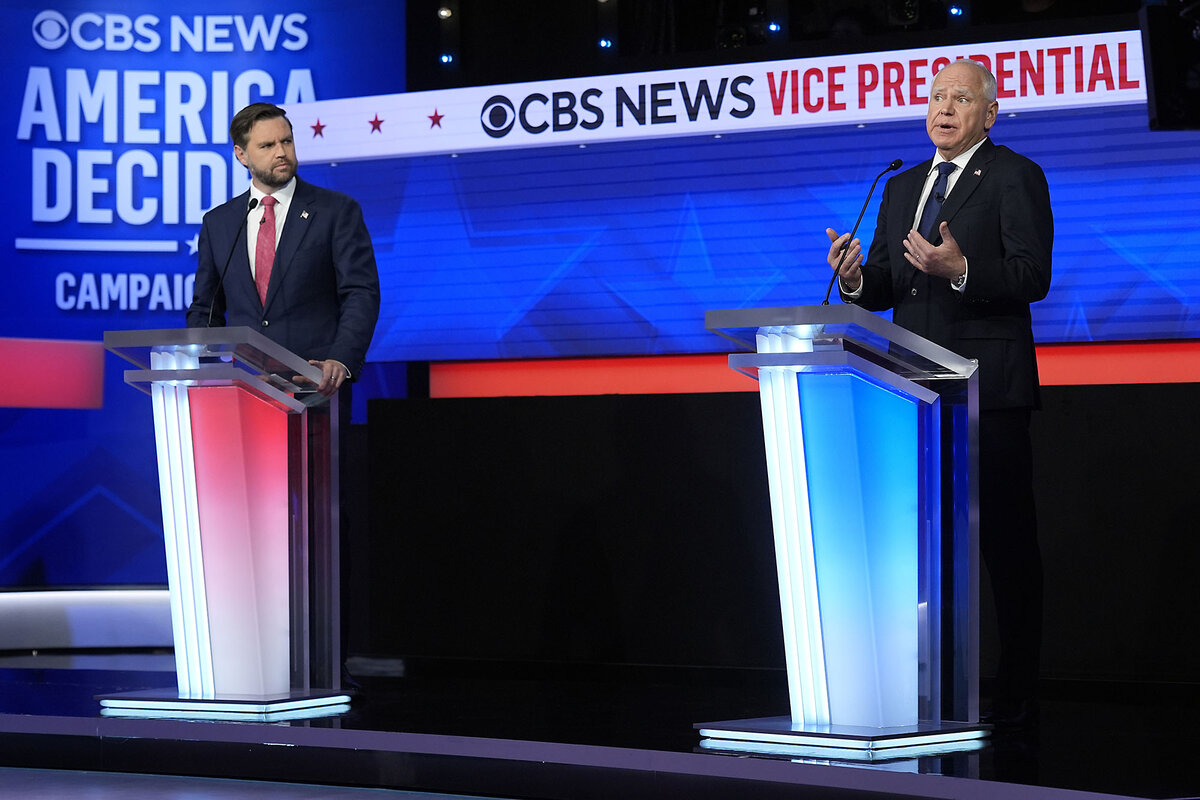

Ohio Sen. JD Vance showed he was the more deft debater when he met Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz onstage for their vice presidential debate Tuesday night, with both candidates taking a much more civil approach than their running mates did onstage last month.

Senator Vance showed a level of polish and empathy onstage that was notably different from his standard political persona, looking to find humanizing moments throughout the evening.

Governor Walz started off haltingly and was the less polished of the two, stumbling over a few points, and missing some opportunities to go on offense. But he landed a hard punch at the end of the debate, flaying Mr. Vance for ducking an answer on whether he thought former President Donald Trump had lost the 2020 election.

Vice presidential debates almost never influence the final outcome of a presidential election – few undecided voters watch the undercard debate – and while there were some stumbles, there were no missteps major enough to live on and haunt their running mates. But the debate, hosted by CBS News in New York, still offered some illuminating moments about the race.

Vance shows polish, Walz hits him on Jan. 6 in VP debate

Ohio Sen. JD Vance showed he was the more deft debater when he met Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz onstage for their vice presidential debate Tuesday night, with both candidates taking a much more civil approach than their running mates did onstage last month.

Senator Vance showed a level of polish and empathy onstage that was notably different from his standard political persona, looking to find humanizing moments throughout the evening.

Governor Walz started off haltingly and was the less polished of the two, stumbling over a few points, missing some opportunities to go on offense, and misspeaking a handful of times. That includes saying at one point that he’d “become friends with school shooters” when he seemingly meant that he’d befriended survivors of school shootings – comments the Trump campaign immediately jumped on with attacks.

But while Mr. Walz didn’t go on the offensive as often, he landed a hard punch at the end of the debate, flaying Mr. Vance for ducking an answer on whether he thought former President Donald Trump had lost the 2020 election.

Vice presidential debates almost never influence the final outcome of a presidential election – few undecided voters watch the undercard debate – and while there were some stumbles, there were no missteps major enough to live on and haunt their running mates. But the debate, hosted by CBS News in New York, still offered some illuminating moments about the race. Here are three key takeaways.

Vance and Walz largely stuck to policy and stayed civil

Compared with the past few debates, this was a lovefest.

After a June debate where Mr. Trump repeatedly eviscerated President Joe Biden, and a September debate where Vice President Kamala Harris repeatedly baited Mr. Trump into overheated attacks, this one took a remarkably civil tone between the two Midwestern candidates.

Mr. Vance struck a sharply different tone than he’d regularly displayed earlier in his political career, leaning into empathy and looking to agree with Mr. Walz as often as possible. His harsh past rhetoric has hurt his image badly with voters – polls show he’s less popular than Mr. Walz, former President Donald Trump, and Vice President Kamala Harris – but on the national stage, he sounded remarkably different.

Mr. Walz and Mr. Vance repeatedly said they agreed on issues and offered each other the benefit of the doubt. Mr. Walz said he believed Mr. Vance was sincere when he said he believes kids shouldn’t face gun violence. And he agreed with Mr. Vance’s criticism of outsourcing. “The rhetoric is good. Much of what the senator said right there, I’m in agreement with him on this,” he said after Mr. Vance talked about how globalization had hurt middle America.

After Mr. Walz told a story of his son witnessing a shooting, Mr. Vance took a moment to offer his condolences: “Tim, I didn't know that your 17-year-old witnessed a shooting. I'm sorry about that. Christ have mercy. It is awful.”

“I've enjoyed tonight's debate, and I think there was a lot of commonality here,” Mr. Walz said near the end of the evening.

Both candidates punched up

While the two men took a notably friendly tone toward one another, they both took some hard shots at the top of the other ticket – the people Americans are actually choosing between to be president.

Mr. Walz blasted Mr. Trump for having called global warming a “hoax” and for pulling out of the Iran nuclear deal, as well as for promising to cut taxes for wealthy people. He also slammed Mr. Trump for convincing congressional Republicans to oppose a bipartisan Senate bill that would have cracked down on border crossings and provided a lot of money for border security.

Mr. Vance repeatedly questioned why Ms. Harris hadn’t actually taken care of her policy proposals while she was vice president. “Day 1 was 1,400 days ago,” he said at one point. “If Kamala Harris has such great plans for how to address middle class problems she ought to do them now, not when she’s asking for a promotion,” he said at another. He also slammed Ms. Harris for the Biden-Harris administration rescinding many of Mr. Trump’s border policies.

Vance dodged a number of questions. (Walz did too.)

Mr. Vance repeatedly sidestepped when asked about his previous rhetoric. He dodged when asked about pushing the conspiracy theory that Haitian refugees in Springfield, Ohio, had eaten their neighbors’ pets, pivoting to a reality-based argument that those immigrants were straining local resources.

Mr. Vance also pivoted when asked why he’d said in a private 2020 conversation that Mr. Trump had “utterly failed” to pursue populist economic policies during his presidency, claiming that he was actually criticizing Congress, not Trump, for not doing more on issues like tariffs.

And he claimed that “When Obamacare was crushing under the weight of its own regulatory burden and health care costs, Donald Trump could have destroyed the program,” but instead chose to work across the aisle to save it. Mr. Trump notably tried to repeal that program, as Mr. Walz pointed out. Mr. Vance also said that he didn’t support a national abortion ban, even though he said during his 2022 Senate run that he supported some national restrictions and signaled support for a 15-week federal abortion ban.

Mr. Walz also obfuscated, delivering a borderline incoherent answer when asked about why he’d incorrectly claimed he was in Hong Kong during China’s crackdown on student protesters in Tiananmen Square in 1989, before admitting that he was sometimes a “knucklehead” who misspoke.

But one of the more striking moments of the debate – and one of Mr. Walz’s best – came at the end. He slammed Mr. Vance for refusing to say Mr. Trump had lost the 2020 election. Mr. Vance dodged, saying he was “focused on the future.” “That is a damning non-answer,” Mr. Walz said.

How a husband-and-wife reporting team gets the news out in Ukraine

Accurate information is essential to civilians trying to survive in a war zone. And when electricity and the internet are unreliable, sometimes a simple printed newspaper is enough to give people what they need to know.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Air-raid sirens have been a round-the-clock reality for weeks in Bilopillia, Ukraine. When the warnings blare, everyone lies flat to take cover or scrambles to underground shelters.

But for Nataliia Kalinichenko and her husband, Yurii, there’s no break from getting the news out to the community. Their mission is to keep locals informed through their weekly newspaper.

“With the onset of Russia’s invasion, our community’s information needs changed dramatically, as did our ability to meet them,” says Ms. Kalinichenko, who joined the newspaper in 1996 and became its editor-in-chief a decade later. “Safety became the primary concern.”

Articles pay tribute to slain soldiers and quote analysts to dispel rumors and dismantle Russian disinformation. One recent instance involved pollution of the river Seim – caused by industrial activities upstream in Russia. Russian trolls spread online the notion that drinking water had also been compromised, but that was not actually the case. Experts quoted in the paper helped debunk that notion.

“For villagers with no internet,” says local shopkeeper Serhii, “it is an important source of information and local news.”

How a husband-and-wife reporting team gets the news out in Ukraine

The streets of this city, just seven miles from the Russian border, are nearly deserted. Air-raid sirens have been a round-the-clock reality for weeks, and people take them seriously: When the warnings blare, everyone lies flat to take cover or scrambles to underground shelters.

But for Nataliia Kalinichenko and her husband, Yurii, there’s no break from getting the news out to the community. They have safety routines; Ms. Kalinichenko asks friends or relatives to monitor social media platform Telegram for news of incoming Russian attacks, while Mr. Kalinichenko uses a drone detector while driving. But their mission is to keep locals informed through publication of their print weekly, Bilopilshchyna.

Before the war, the newspaper featured 12 to 16 colorful spreads with articles on local entertainment, politics, and practical information like bus schedules. Now, it is a stark black-and-white publication filled with military and civilian obituaries and snapshots of local buildings destroyed by Russian attacks.

“With the onset of Russia’s invasion, our community’s information needs changed dramatically, as did our ability to meet them,” says Ms. Kalinichenko, who joined the newspaper in 1996 and became its editor-in-chief a decade later. “Safety became the primary concern.”

“Many newspapers operating in the border regions remained in their places if the security situation allowed. Others relocated further away from the front. But they all work for their readers,” says Liudmyla Pankratova, director of the Regional Press Development Institute, a nonprofit in Kyiv. “Supporting regional newspapers should be a priority now.”

“The role of regional publications in remote frontline communities has increased. This is because people need information from media they trust,” she adds. “And people trust those they know: relatives, friends, neighbors. Moreover, journalists themselves live next door to them. So they can pass on information about community problems to the outside world.”

The news must go out

The information landscape has transformed over the past 2 1/2 years. Televisions, once tuned to Russian and Ukrainian channels, lost their appeal. The first Russian strike on the town’s television tower in March 2022 marked the beginning of a series of barrages. Telegram, which now tracks incoming missiles, has become a lifeline – though it requires electricity and an internet connection. Both have been hard to reliably access amid Russia’s offensive.

Ms. Kalinichenko says Russian Grad rockets and artillery shells have killed 16 people, including two children, in Bilopillia since the war began. And while Ukraine’s offensive into Russia’s Kursk region moved Bilopillia outside the range of their rockets, the town is still vulnerable to glide bombs and the constant threat of ballistic missiles.

Inevitably, the community has shrunk. The agricultural district of Bilopillia was once home to about 16,000 residents. Now the figure is between 3,000 and 8,000, according to Ms. Kalinichenko. Residents come and go depending on attacks and electricity supplies. New arrivals from other regions temporarily swell the numbers.

The Kalinichenkos are determined to stay put and keep the paper running as a team. On the walls of their office hang photographs documenting the paper’s history, including a period when it was known as the Flag of Stalin. Piles of newspapers are testament to disruptions in postal delivery services, and a collapsed ceiling from a recent blast prevents Ms. Kalinichenko from sitting at her usual desk.

At a nearby shop, salesperson Nina Davydova and her teenage daughter, Victoria, discuss the toll of constant strikes. Though Victoria gets her news only through Telegram, Nina says Bilopilshchyna is still popular.

“People really like to buy the newspaper,” she says, pointing out that she has already sold six copies this morning, even though Russian attacks were particularly intense. “Grandmothers will buy five to six copies so that they can bring it to their neighbors who cannot walk.”

“If people would not buy it, I would not sell it”

The newspaper sells at 20 locations in the Sumy region, which shares a 28-mile border with Russia. While many readers have fled, they continue to pay for a subscription in order to remain connected to their homeland, says Ms. Kalinichenko. Even in its reduced format, it serves as a vital source of information for local agricultural communities.

Serhii, a sardonic shopkeeper, displays the latest copies alongside shrapnel that damaged his shop, which sits a few blocks from Nina’s. “If people would not buy it, I would not sell it,” he says. “About five people buy it every day. But people also come from surrounding villages on market days to buy 10 copies at a time.”

Articles pay tribute to slain soldiers and quote analysts to dispel rumors and dismantle Russian disinformation. One recent instance involved pollution of the river Seim – caused by industrial activities upstream in Russia. Russian trolls on Telegram spread the notion that drinking water had also been compromised, but that was not actually the case. Experts quoted in the paper helped debunk that notion.

“For villagers with no internet, it is an important source of information and local news,” says Serhii.

That assessment is echoed by customer Dymtro Potiomkyn, who grew up with the paper on the family table. He recalls it being a way for people to buy and sell goods locally. Today, it publishes information about what kind of social help is available locally. He buys the paper in person, while his mother gets it delivered by mail.

“This newspaper is crucial for villages that are right on the border with Russia,” says Mr. Potiomkyn, who runs a funeral business in the region. “Some have been without electricity or internet for years. It’s literally their only source of Ukrainian news.”

Oleksandr Naselenko supported reporting of this article.

Her power in Poland came accidentally. She kept it with stamina – and Facebook.

Poland was a key player in the fall of Soviet communism. This trusted elder Polish stateswoman helped create democratic practices and continues even today as a Facebook influencer.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

If it was a wallflower Polish communists wanted in throwing a bone to democratic factions in 1987, it turned out to be a miscalculation of historic proportion when they drafted an obscure legal scholar, Ewa Łętowska, to be a human rights ombudsman.

They launched a stateswoman whose legal expertise on how to be democratic has echoed down the decades right onto Facebook. At 84, Ms. Łętowska has 35,000 followers on the platform, and her thoughts regularly go viral.

She was among a class of progressive technocrats that quietly bloomed in the politically fertile era of rebellion surrounding the fall of the Soviet empire. They performed the essential construction of a democratic legal framework – writing the Polish Constitution.

Ms. Łętowska’s value to Polish society cannot be overstated, says Helena Chmielewska-Szlajfer, a sociologist at Koźmiński University. “She’s a living legend, and she has the authority of this wise, powerful woman who set the institutions right in the beginning. She worked on this at a time it was the hardest – the intermediary stage between communism and democracy. And she still has much to say.”

Her power in Poland came accidentally. She kept it with stamina – and Facebook.

It was late fall of 1987 in Poland, and the economic and social forces here were fueling tremors that would eventually fell communism across the Soviet bloc.

Among a group of influential men – law professors – at a dinner party one evening was a Communist Party member brainstorming how to throw a bone to pro-democracy activists. The group was tasked with floating a name for a human rights ombudsman; that of legal scholar Ewa Łętowska kept surfacing. A devoted academic who had pumped out two decades of legal research on topics as benign as consumer protections and contract law, she was a respectable but safe choice.

“They said, ‘We want a woman, because women might be easier to manipulate,’” Ms. Łętowska says in an interview in her Warsaw flat, lined floor to ceiling with books and opera records. She laughs at this memory that she possesses only because her lawyer husband was among the men feasting on schnitzel at that monthly table for regulars.

If it was a wallflower they wanted, it turned out to be a miscalculation of historic proportion: They launched a stateswoman.

Her trajectory as Poland’s top human rights thinker, she says, started “loudly, and with a bang” when she was named the country’s human rights ombudsman soon after the dinner party, pioneering the balance between the state and the individual in the waning days of communism.

She was an accidental influencer who, four decades later, now in her 80s, is a sought-after talking head, issuing viral social media posts about democracy. And when voters sent their right-wing government packing last October, a coalition of progressives turned to the wisdom and experience of Ms. Łętowska and her contemporaries.

They’re looking for help to fix Poland’s institutions after the populists turned the country away from the European Union, rolled back civil rights such as abortion, took over the media and judiciary, and questioned the country’s humanitarian aid duties.

Ms. Łętowska value to Polish society cannot be overstated, says Helena Chmielewska-Szlajfer, a sociologist and assistant professor at Koźmiński University. “She’s a living legend, and she has the authority of this wise, powerful woman who set the institutions right in the beginning. She worked on this at a time it was the hardest – the intermediary stage between communism and democracy. And she still has much to say.”

A trip to Hamburg opens her eyes

In 1980, the world saw burly Solidarity unionist Lech Wałęsa leading a revolt against communist authorities for worker rights – and eventually winning a Nobel Prize for it. But it was the progressive technocrats quietly blooming in that politically fertile time who did the less spectacular but essential work of building a democratic legal framework.

Until then, Ms. Łętowska had forged her career as an impartial civil law professor, neither courting the communist regime nor joining the opposition. For instance, she’s on the record saying that the communist martial law of the early 1980’s was “grim” but that she didn’t have enough information to say whether it was “necessary.”

Ms. Łętowska now confidently says she was “a success [as ombudsman]. I was a state official to society, who brought more dialogue, more transparency. At the same time, I didn’t want a political future.”

In an era when one didn’t easily trust one’s neighbor, there was little subversive in her ‘good girl’ youth to suggest she would emerge a strong voice for human rights and democracy. She channeled her incessant curiosity into books and music – a passion that would later drive her to bring in literature and records that were difficult to obtain from behind the Iron Curtain.

On rare study trips abroad — few Polish scholars were trusted to leave the country — she might use German colleagues’ photocopiers to reproduce expensive legal tomes, like handbooks and casebooks on human rights law. Other times she would barter in the West, swapping her sought-after Soviet records for volumes published there.

After law school in the 1960s, she published articles about civic law issues, rising through the ranks as a professor at the Polish Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Law Studies.

A trip to the West – Hamburg, Germany – in the early 1980s was a turning point. She happened upon a demonstration by feminists who were “shabby, with unkempt hair, shouting.” She has forgotten what they were protesting, but from the other side of the street, she could see citizens hurling insults at the women.

“And in between you could see a line of police, with stone faces making sure no one gets hurt, being completely indifferent, and providing this space for demonstrating,” says Ms. Łętowska. “It was the first time in my life I saw police not beating demonstrators – but rather protecting them. This is how I finally understood how things should be.”

”The people of Hamburg would never know how much credit they should take, quite by accident, in my education,” she says.

Staring back at Big Brother

Half a decade after that trip, she was named Poland’s first human rights official, judging the conduct of the state toward its citizens. If Big Brother had once peeked over her shoulder, she was now turning around and staring back.

Should political parties have to register with the state? No, she famously wrote in 1988, when Poland was still under communist rule: “The constitution stated clearly: if parties want to form, let them form. Registration is required only for associations.”

“It was a big deal, when I wrote that,” says Ms. Łętowska says, raising her eyebrows as she lifts a cup of tea.

A few years later, when the police called in state television to film an arrest for demonstrative purposes, as they searched a citizen’s home, she says, “I criticized that. I wrote that basic human rights pacts say privacy should be protected.”

These were important symbolic steps, among many, that demonstrated to the watching public that the regime needed to bend to obey the law — and not the other way around.

After the communist regime fell in 1989, she found herself among the legal scholars helping to modernize the Polish Constitution. Describing the pioneering nature of how they crafted the founding documents, she smiles: “One of my colleagues would be sitting in the library at Parliament … and came up with the now fundamental phrase ‘The Republic of Poland shall be a democratic state ruled by law.’”

In 1999, she was named to one of the nation’s highest courts, and three years later, at age 62 she rose to be a judge of the Constitutional Tribunal, responsible for judging compliance with the constitution of everything from tax reforms to trade agreements. She officially retired from the tribunal in 2011, having delivered public judgments for nearly 100 cases, but continues to mentor law students today.

Her role in shaping history gives her gravitas today as “one of the most important figures defending the rule of law, and also one of the most vocal of all the legal experts,” says Weronika Kiebzak, a legal analyst with Polityka Insight.

Across Ms. Łętowska’s desk passed early, urgent questions about individual privacy and human rights – foreign concepts under communism. Her most forward-thinking ideas came with her insistence that all courts, from the highest down to the most local, should be able to interpret the constitution. “She wanted judges to have more courage – ‘dispersed constitutional control,’” says Ms. Kiebzak, but the idea was never implemented.

That lonely position she staked out decades ago gained fresh urgency when populists took over the tribunal during the last government, leaving no other body with the authority to interpret the constitution.

“My God, how they cursed me” in the 1990s, she says now. “But if they’d taken the trouble to do it right earlier...”

A quieter voice, but still heard

Most days, Ms. Łętowska sips tea in her home, spending hours reading, writing, and fielding media calls. (She turned down four calls during the afternoon the Monitor spent with her.) She will also travel to conferences and public events as an invited speaker.

She’s busy being 84. Harder of hearing, slower of step, she’s keenly aware of her age. ”I have no family; I’m completely alone,” she says. But she indulges her sparky stamina. A trainer comes to her flat several times a week, and she can do 20 “lady pushups.”

Ms. Łętowska also reminisces about her husband, who died in 1999, mourning their record collection, which she is giving away. As her hearing declines, she can no longer fully enjoy it. “It was a very valuable collection,” she says, eyes resting momentarily on an empty space on a bookshelf.

But her nation, rebuilding after stumbles, draws on her elder wisdom today as it did in its early days of democracy. “I’m a lawyer and adviser …. The most I can say is that ‘if you do this, it will work out here but not here,” she says of her legal tinkering.

Her theorizing often plays out across social media, such as in a lengthy Facebook post last summer to her 35,000 followers that was shared hundreds of times. The post started with a nod to her own continuing role as arbiter. “We keep asking what is the law?” she wrote. “What will the expert say?”

Might her most important thinking be ahead?

“As long as I’m mentally fit, I’m here to offer my thoughts,” she says, remaining exactly as she was when she first came into Poland’s consciousness – an accidental influencer.

Piotr Żakowiecki contributed to this report.

Essay

Mrs. Tippet’s school of life: The teacher who made me fall in love with writing

The profound impact of good teachers, mentors, and role models is difficult to overestimate. It’s a gift that shapes our very values, character, and trajectory, and one that, as our writer discovered, lasts a lifetime.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Vicki Cox Contributor

I don’t remember a thing I learned in fifth grade about math or science or social studies. What I do remember is my teacher, Mrs. Tippet, and the impact she had on my life.

The best part of our day was after recess. We would come in from recess hot and sweaty and distracted. She would have us lay our heads down on our desks and read us stories of grand adventures from around the world.

One series featured Martin and Osa Johnson, who traveled through Africa. In those 20 minutes, with our heads on our desks in a small Midwestern town, we traveled to faraway places and met fascinating people. It was in the upstairs classroom with no air conditioning that I understood the powerful images that words could make.

I am now far older than Mrs. Tippet was teaching our class. My hair is grayer, and my clothes are more out-of-date. Yet her influence endures. Today, I’ve published hundreds of articles and written 15 books all because of Mrs. Tippet and those 20 minutes after recess.

Mrs. Tippet’s school of life: The teacher who made me fall in love with writing

I don’t remember a thing I learned in fifth grade about math or science or social studies. I know I learned something because I was promoted to sixth grade. But those lessons left no mark on my psyche.

What I do remember is my teacher, Mrs. Tippet, and the impact she had on my life. She dressed as if she had just stepped out of a Norman Rockwell painting. She was tall, and she carried herself like she enjoyed being that way. She wore ladylike lace-up black heels, dark skirts, and white blouses that fell gracefully around her arms. She pinned a little gold watch on her shoulder, which she proudly told us “her darling husband” had given her. Mondays through Thursdays, she’d wear her chestnut hair in braids crisscrossed over the top of her head. Fridays, she dressed up, arranging her hair in an elegant chignon at the nape of her neck, with a gold cameo at her throat.

I loved Mrs. Tippet. I used to invent reasons to go to her desk to drink in her lovely scent, or was it the kindness that surrounded her? Though it was not required, I’d bring my papers to her to examine.

I stood on one foot and then the other, hoping she’d write “Excellent” across the top with her gold-tipped fountain pen. She’d start the capital letter with swirls and flourishes as if it was something really important I had done, so important I should save it – which incidentally, I have done for 60 years, and I still feel proud.

She tolerated no mischief, not that there was much. Most of us did not want to disappoint her; a small group feared her. Of course, John Phillips would whisper to Ronnie Reeves when she was writing on the blackboard or helping someone at their desk. She never raised her voice, but the look on her face was so cold even they could not hold back their regret. Some of us secretly were glad they got what they deserved; some were sorry for them. But we all were relieved we weren’t the ones who froze the room.

She corrected me once, too. We were supposed to make a poster about Veterans Day. Not surprisingly, most drew flags, tombstones, and crosses. All except for Patty Bussen, who drew a large poppy on her paper and colored it deep red. I liked what she did and copied her. Mrs. Tippet walked around the room as we worked. She stopped at my desk and asked me if the design was my own idea. Oh, yes, I assured her. It came right out of my own head. She looked at me for a long time and then walked on. I knew she knew what I had done and was immediately ashamed.

She replaced the cursive charts with our drawings above the blackboard: 28 pictures of tombstones, crosses, and flags – and two with one large poppy drawn in the middle. Patty’s won first place in our room contest. Mine won nothing. So obvious was my theft that I could not wait for Mrs. Tippet to take the pictures down. The shame was punishment enough. I never copied anyone else again – in fifth grade or anytime after. That was one thing I remember from fifth grade: Dishonesty has its own reward.

The other thing Mrs. Tippet taught me was never measured on an end-of-year achievement test, either. We would come in from recess all hot and sweaty, still thinking about whom we’d next pick at kickball or how many times we could double-jump next time we played outside. She would have us lay our heads down on our desks. I know now it was a ploy to settle us down for the afternoon’s work. To me, it was the best part of the day. She would read us stories of grand adventures from all over the world.

One series featured Martin and Osa Johnson, who traveled through Africa, exploring wildlife. I imagined Martin had big feet just like my dad’s, and Osa had chestnut hair that crisscrossed her head just like Mrs. Tippet’s. In those 20 minutes, with our heads on our desks in a small Midwestern town, we traveled to faraway places and met fascinating people. It was in the upstairs classroom with no air conditioning that I understood the powerful images that words could make.

As I grew up, I secreted poems in a black notebook and recorded stories of the people and region around me. At first, they were just the bumblings of a preteen mind, but eventually, I could use the power of words to weave stories for others to read. Today, I’ve published hundreds of articles and written 15 books all because of Mrs. Tippet and those 20 minutes after recess.

I am now far older than Mrs. Tippet was teaching our fifth grade class. My hair is grayer, and my clothes are more out-of-date than hers ever were. Yet her influence endures. She touched something in me that was already there; she helped me realize it. “Be magnanimous,” she’d say. At class reunions, I’d see this actualized.

In the gallop to press children to blacken the correct circles in society’s expectations today, I hope students find an educator who is their generation’s Mrs. Tippet, a teacher who opens their eyes to what they are and could yet be. I know she would be pleased and write “Excellent” across their lives in swirling capital letters with her gold-tipped fountain pen.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Civility’s art of listening

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The vice presidential debate on Tuesday may have set a new and more virtuous reference point in the history of such events. During a segment on gun violence, Gov. Tim Walz noted that his teenage son had witnessed a shooting at a community center. “Tim, first of all, I didn’t know that,” replied his opponent, Sen. JD Vance. “And I’m sorry about that. ... It is awful.”

That moment of empathy capped a turn toward civility as refreshing as it was rare in national politics these days. And, in their readiness to find agreement amid their policy differences, the two political opponents – and the moderators nudging them toward clarity and decorum – showed that the tensions inherent in democracy can be resolved in deliberation elevated by reason, humility, and respect.

Perhaps this debate marks a turn toward calm deliberation in politics. As the candidates and moderators showed, when journalists coax listening over conflict, civility returns to civic discourse.

Civility’s art of listening

In the history of American vice presidential debates, no line is more engraved in public memory than Lloyd Bentsen’s 1988 smackdown of Dan Quayle for trying to draw a personal parallel to John F. Kennedy.

The encounter on Tuesday between this year’s candidates for the second-highest federal office may have set a new and more virtuous reference point. During a segment on gun violence, Gov. Tim Walz noted that his teenage son had witnessed a shooting at a community center. “Tim, first of all, I didn’t know that,” replied his opponent, Sen. JD Vance. “And I’m sorry about that. ... It is awful.”

That moment of empathy capped a turn toward civility as refreshing as it was rare in national politics these days. American democracy, notes Harvard academic David Moss, is a relentless struggle of competing ideas “made productive, ultimately, by a deep faith in – and shared commitment to” the ideal of self-governance.

In their readiness to find agreement amid their policy differences, the two political opponents – and the moderators nudging them toward clarity and decorum – showed that the tensions inherent in democracy can be resolved in deliberation elevated by reason, humility, and respect.

Those qualities, in fact, are driving a vigorous self-reflection and renewal among some journalists – particularly at the local level – at a time when their industry is contracting and public trust in public institutions and the media is low. On average, two newspapers close every week in the United States. That has a civic corollary. A 2022 Gallup/Knight Foundation survey found that 71% of Americans who distrust national news outlets also have less faith in the country’s political process.

Yet that same survey found that more than half of respondents feel local journalists care about the communities they cover. A June summit of rural media hosted by the American Press Institute (API) drafted a new “playbook” for building that trust. In July, the public radio station WITF in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, hosted a forum to boost civic unity. It brought its listeners together to hear them out.

“Today, journalists are more intentionally activating their roles as community convener, conversation facilitator and resource connector,” write Samantha Ragland and Kevin Loker of API. That convening role, they note, requires humility, empathy, compassion, and hope. “For journalists to prioritize the people they serve, they’ll need to become experts at centering people: their voices and experiences, their relationships and connections.”

In an essay in Columbia Journalism Review, New York Times Chairman A.G. Sulzberger wrote last year that “Common facts, a shared reality, and a willingness to understand our fellow citizens across tribal lines are the most important ingredients in enabling a diverse, pluralistic society to come together to self-govern.”

Perhaps the vice presidential debate marked a turn toward calm deliberation over finger-pointing debate. As the candidates and moderators showed, when journalists coax listening over conflict, civility returns to civic discourse.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The divine ‘Us’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

Recognizing our – and everyone’s – inherent unity with God, our divine Parent, lifts us out of a divisive “us” and “them” outlook.

The divine ‘Us’

Imagine a sense of “us” and

“them” not so indelible, but

more an empty notion to be

simply erased – the way a

line drawn in the sand just

goes as water washes over it.

I consider the sun and its

radiance, one indivisible whole,

a kind of altogether brilliant

“us” – no shafts called “them” shut

out or separate, as if the sun

didn’t hold within itself the very

shine of its every ray.

Prayerfully I take this in – this

hint of the enveloping blessed

Us: our divine parent, God – Love

itself, pure good – flawlessly

one with all of us: spiritual,

bright, equally-loved-by-Love

children of God – everyone the

reflection of God’s goodness.

This spiritual truth – Christ’s

message, ever streaming into

consciousness – can fill all

corners of our open thought,

washing away every invalid,

clung-to limit.

Blaming lets up, dug-in heels and

opinions are let go, until entrenched

views of “us” and “them” vanish

like a shadow – all at once gone

in the full blaze of grasping our

unity with God, with each other

– a unity altogether divine.

Viewfinder

A new day

A look ahead

Thank you for spending time with the Monitor today. Tomorrow, we’ll take you to the U.S. Supreme Court to look at the most high-profile cases of the new term. We’ll also explore how being an Ivy League president isn’t as appealing as it once was.