- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Trump promised to pardon Jan. 6 felons. Where does that stand now?

- Today’s news briefs

- When Hezbollah rockets are incoming, and you can’t reach the shelter

- Trump prepares for ‘economic warfare’ with China

- Women in construction find solidarity as ‘sisters in the brotherhood’

- John Lewis served as ‘the conscience of the Congress’

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

An extraordinary man and his message for today

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

“You have to love that person who’s hitting you.” That is a quote from civil rights icon John Lewis in today’s review of a new biography.

Why is that true? The pioneer of modern nonviolent resistance, Mohandas Gandhi, came to a startling conclusion. Injustice comes from the desire to control others, which plays upon our passions and prejudices. Truth comes from the struggle to control oneself without yielding to despair or hate. In its most radical forms, this becomes a transformational grace that changes people and societies through conscience, not through control.

It is the amplitude of a pure heart, unabridged and unleashed, and a power that does not wax or wane with the political seasons.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

The Explainer

Trump promised to pardon Jan. 6 felons. Where does that stand now?

The Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol shook the peaceful transfer of power after a national election. President-elect Donald Trump says he’ll pardon many of the convicted rioters – a potentially controversial precedent.

For millions of Americans, Donald Trump’s election victory was a cause for celebration. But for a select group, it meant more: the prospect of legal vindication.

When Mr. Trump ascends the Capitol steps in late January for his second inauguration, he will be standing where thousands of his supporters stormed the building four years prior. Protesting what he claimed was a “steal” of the 2020 election – without conclusive evidence of fraud that could have swayed the outcome – Mr. Trump’s supporters attacked police officers, smashed windows, and ransacked congressional offices, trying to keep him in office.

Since then, the U.S. Department of Justice has charged over 1,100 individuals with crimes related to the Jan. 6, 2021, riots. Mr. Trump has promised to pardon all of these defendants. And while this use of executive clemency is troubling to some who condemn the assault on the Capitol, that act of clemency would in fact be constitutional.

The pardon power exists because America’s founders “wanted to provide some kind of check on the prosecutorial power of the executive,” says Michael Gerhardt, a professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law.

“It’s a way to correct an injustice,” he adds. “That’s how Trump will see it.”

Trump promised to pardon Jan. 6 felons. Where does that stand now?

For millions of Americans, Donald Trump’s election victory was a cause for celebration. But for a select group, it meant even more: the prospect of legal reprieve.

When Mr. Trump ascends the Capitol steps in late January for his second inauguration, he will be standing where thousands of his supporters violently stormed the building four years prior. Protesting what he claimed was a “steal” of the 2020 election – without conclusive evidence of fraud that could have swayed the outcome – Mr. Trump’s supporters attacked police officers, smashed windows, and ransacked congressional offices, trying to keep him in office.

Since then, the U.S. Department of Justice has charged over 1,100 individuals with crimes related to the Jan. 6, 2021, riots. As he campaigned for a second term, Mr. Trump promised to pardon at least some of these Jan. 6 defendants. After he secured victory, those followers celebrated not just his triumph, but also the prospect of their own freedom.

Some who condemned the Capitol attack may find this use of executive clemency troubling. For example, at a sentencing in April, federal Judge Royce Lamberth warned of Americans resorting to “vigilantism, lawlessness and anarchy” if they don’t like election results.

Yet pardons would be perfectly constitutional. The pardon power exists because America’s founders “wanted to provide some kind of check on the prosecutorial power of the executive,” says Michael Gerhardt, a professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law.

“It’s a way to correct an injustice,” he adds. “That’s how Trump will see it.”

Where do the Jan. 6 cases stand now?

Six people died during or following the Jan. 6 attack, and some 140 police officers were injured, according to the Justice Department.

As of January, the department said 749 federal defendants have received sentences for criminal activity on Jan. 6. Charges in the attack have ranged from felony assault and use of a deadly or dangerous weapon, to misdemeanor entering or remaining in a restricted federal building.

The president has the power to issue a pardon, which would free a defendant and erase all records of that person’s criminal offense. However, the person charged or convicted must accept responsibility for the crime. As president, Mr. Trump could also issue a commutation, which would shorten or lessen a defendant’s sentence but keep their original offense on the books. Lawyers for some of the Jan. 6 defendants have already begun asking for sentencing delays.

Lawyers for one defendant, Christopher Carnell of North Carolina, filed a motion Wednesday asking to delay a hearing in the case due to the election result. Citing President-elect Trump’s “multiple clemency promises,” his lawyers wrote that Mr. Carnell, a “nonviolent entrant to the Capitol on January 6, is expecting to be relieved of the criminal prosecution that he is currently facing when the new administration takes office.”

The judge overseeing the case denied that request, but other Jan. 6 defendants are optimistic that they will be granted early release. One is Ronald McAbee, a former sheriff’s deputy in Tennessee sentenced in February to 70 months in prison on six felony charges – including assaulting an officer – related to his participation in the Capitol riot.

“Sitting in prison, listening to the election results ... I feel vindicated,” wrote Mr. McAbee in a note that his wife posted on social media. “Donald Trump has been elected ... and we are coming home! All the hardships we have endured are coming to an end.”

What kind of power does Trump have here? What has he promised?

The presidential pardon power is broad. Article 2 of the Constitution says the president can “grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.” Perhaps the most famous presidential pardon came when Gerald Ford pardoned Richard Nixon after the Watergate scandal.

“There aren’t really restrictions,” says Mark Osler, a University of St. Thomas School of Law professor.

“You can take issue with the morality of it, the policy of it, but not that he has the power to do it,” he adds.

Mr. Trump issued 138 pardons during his first term, including for political allies like Steve Bannon and Paul Manafort. Other pardons went to conservative celebrities like Joe Arpaio, an Arizona sheriff convicted of criminal contempt involving the treatment of unauthorized immigrants, and Dinesh D’Souza, who pleaded guilty to making illegal campaign contributions.

Describing the Jan. 6 defendants on the campaign trail as “political prisoners,” Mr. Trump promised on multiple occasions to pardon at least some of them. “If they’re innocent, I would pardon them,” he said in July.

The Trump campaign said, before the election, that he would decide pardons “on a case-by-case basis when he is back in the White House.”

For Professor Osler, that suggests “It’s going to be some [Jan. 6 defendants], not all” who receive clemency.

What would be the significance of such pardons, on this scale?

A widespread pardon of potentially hundreds of federal criminal offenders would represent an unusually sweeping and premeditated use of the pardon power.

President Jimmy Carter, who in 1977 fulfilled a campaign promise by pardoning hundreds of thousands of men who evaded the Vietnam War draft, is believed to be the only other president to make such a promise.

“We don’t see presidents talk about using the pardon power before they take office,” says Professor Osler. “It’s a very unusual promise to make,” he adds. “We’ll see how that plays out.”

President Carter’s blanket action proved controversial. George Washington’s pardon of participants in the Whiskey Rebellion – the first-ever use of the pardon power – was also unpopular with some.

A broad pardon of the Jan. 6 defendants is likely to be controversial as well. Some experts say it would be a troubling precedent, especially with regard to future elections.

A blanket pardon “sends a message of condoning violence against the United States and [condoning] violence to contest an election in the United States,” says Rachel Barkow, a professor at the New York University School of Law.

“If he commutes sentences or reduces them,” she adds, “that would say maybe that what they did is not OK, but they were overpunished.”

Editor’s note: This article was updated Nov. 15, the date of original publication, to make a reference to claims of election fraud clearer and more accurate.

Today’s news briefs

• Trump appoints RFK: President-elect Donald Trump announces he will nominate vaccine skeptic Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to lead the Department of Health and Human Services.

• APEC in Peru: Representatives from 21 Pacific Rim members are meeting in Peru for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum.

• Abu Ghraib detainees: A jury in the United States has awarded $42 million to three former detainees of Iraq’s notorious Abu Ghraib prison, holding a Virginia-based military contractor responsible for contributing to their torture and mistreatment two decades ago.

• Sri Lanka election: The party of Sri Lanka’s new Marxist-leaning President Anura Kumara Dissanayake has won a two-thirds majority in Parliament, providing a strong mandate for his program for economic revival.

• Onion purchases Infowars: The purchase of Alex Jones’ Infowars at a bankruptcy auction by the satirical news publication The Onion is the latest twist in a yearslong legal saga.

When Hezbollah rockets are incoming, and you can’t reach the shelter

Hezbollah’s intensified rocket barrages against northern Israeli communities have created two conflicting impulses among residents: They support the war against Hezbollah, yet are eager for it to end.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Lusi Shinder was born in a ghetto during World War II, and grew up in what is now Ukraine before immigrating to Israel weeks before the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Conflict has been the backdrop of her life.

But as Hezbollah’s increased fire has reached deeper into northern Israel, she says what she and others are experiencing is “another level” – missiles and drones intercepted overhead or hitting residential areas like her own, people running to shelters, the ground shaking.

Across northern Israel, one thinks twice before meeting a friend for coffee, and says a prayer before heading out on the roads.

Residents say they are anxious for the war with Hezbollah to end. It began over a year ago when the Iran-backed Lebanese militia began firing into northern Israel, driving 65,000 people from their homes. At the same time, most support Israel’s invasion of southern Lebanon to push Hezbollah’s forces farther from the border. Otherwise, they fear, Hezbollah could carry out a version of Hamas’ Oct. 7 massacre.

“It’s terrible. They keep firing at us to show us they still can,” says Zeev Glabauch, a repairman from a suburb of Haifa. “It does not matter what deals you might make with them; they don’t want us here.”

When Hezbollah rockets are incoming, and you can’t reach the shelter

Lusi Shinder was in her living room watching the news on television last week when she heard the unmistakable wail of an air raid siren. It has become a near-daily occurrence over the last two months in this northern Israeli community, but it is always jarring.

Heart pounding, she rose and clutched her walker, making her way down the hall to a protected room. She had just closed its door when she heard a boom so loud she knew immediately her building had been hit.

“I came out, and I was in shock. I was like a robot. I saw shattered glass, chunks of debris, smoke,” she says.

A rocket fired by Lebanon’s Hezbollah militia had crashed through her roof, leaving a gaping hole and a staircase coated in dust and chunks of concrete. Later she saw the rooftop pergola – under which she and her family had hosted holiday meals and birthday celebrations – hanging in shards, rubble everywhere.

For Ms. Shinder, who was born in a ghetto during World War II, and grew up in what is now Ukraine before immigrating to Israel just weeks before the 1973 Yom Kippur War, conflict has been the backdrop of her life.

But as Hezbollah’s fire has increased and reached deeper into northern Israel, what she and others are experiencing is, she says, “another level” – missiles and drones intercepted overhead or hitting residential areas like her own, people running to shelters, hillsides and cars burning, the ground shaking.

Across northern Israel, where schools only recently reopened, nature reserves remain closed. In Kiryat Motzkin, a suburb of the port city of Haifa, the zoo remains shuttered, as does its popular theater. All public events have been canceled.

One thinks twice before meeting a friend for coffee, and says a prayer before heading out on the roads. Businesses are suffering.

Support for war ... and its end

Residents say they are anxious for the war with Hezbollah to end. It began over a year ago when the Iran-backed Lebanese militia – in solidarity with its Palestinian ally Hamas the day after its brutal Oct. 7 assault – began firing into northern Israel, driving 65,000 people from their homes.

At the same time, most say they support Israel’s ground invasion of southern Lebanon to root out Hezbollah’s weapons-laden tunnels and hideouts, and push its forces farther from the border. Otherwise, the residents fear, Hezbollah could carry out a version of the massacre and mass hostage-taking that occurred along the border with Gaza.

In September, after nearly a year of incremental escalation along the Lebanon-Israel border, Israel dramatically intensified its campaign, assassinating much of Hezbollah’s leadership, including Hassan Nasrallah, killing and wounding hundreds of its operatives, and striking deeper inside Lebanon.

Hezbollah expanded its fire and threatened to make Haifa, Israel’s third-largest city and an important industrial base, into “the next Kiryat Shmona,” a reference to an Israeli border city in the Upper Galilee that for years has taken the brunt of Hezbollah barrages.

On Ms. Shinder’s roof, repairman Zeev Glabauch hoists a door that was warped and bent from the force of the blast onto his back.

“It’s terrible. They keep firing at us to show us they still can, even after Nasrallah has been killed,” he says. “It does not matter what deals you might make with them; they don’t want us here. They want this state for themselves,” he adds, referring to both Hezbollah and Hamas and recent efforts to secure a cease-fire deal with Hezbollah in Lebanon.

One minute to find shelter

Mr. Glabauch lives in a next-door Haifa suburb called Kiryat Bialik, part of a cluster of communities known collectively as the Krayot that have experienced the intensified Hezbollah fire. One of the apparent targets is Rafael, a weapons manufacturer.

On Monday some 100 rockets were fired at the Krayot in one of the conflict’s largest barrages. Two buildings were hit, and nine people were wounded. Plumes of black smoke billowed into the sky from a normally quiet street where several cars caught fire.

On Tuesday two people were killed further to the northeast, in the Galilee. Two soldiers were wounded by a drone Thursday south of Haifa, and three people were wounded in Kiryat Bialik Friday.

Mr. Glabauch lives in an eight-story apartment building where residents of its 32 units share a single bomb shelter in the basement. He lives on the fifth floor, and typically with only about a minute to get to safety, he and his wife must seek shelter instead in the stairwell along with their upper-floor neighbors.

“We run to the stairs. This is our life. Along with dogs, babies, children, and all the noise,” he says. When awoken by sirens, they rush there in pajamas.

But most of all, he says, he fears driving on the roads, where there is nothing to do in the moment of an attack but stop the car, find a sidewalk or shoulder to lie down on, and cover one’s head.

Jewish Israelis are not the only ones affected by the Hezbollah barrages.

Laura Samara, a film producer, is a Palestinian citizen of Israel who lives in Haifa. She says she does not identify with Hezbollah or Hamas. Rather, she relates more “to the misery of the people.”

“The thing I feel most is that everything is on hold. You cannot plan things,” she says. “You wake up in the morning, and you are waiting for the siren.

“It takes place usually once or twice a day, and you want it over so you can do things like go to the supermarket. The crazy thing is it feels like a lottery – you don’t know if a fragment of a missile or a missile will hit you.”

“All in the same boat”

In Haifa’s Arab neighborhood of Wadi Nisnas, a place of narrow alleyways and stone houses where neighbors regularly share coffee and homemade cookies, some are outspoken against Hezbollah.

“To live here is very hard,” says Fiaruz Hashem, sitting in the stone courtyard of her sister’s home. “My grandchildren are scared when they hear a siren and go where they are told to hide – the safest place, which is in their hallway.

“I’m angry at Hezbollah,” she says, “not just because of what we are suffering, but that the Lebanese have to suffer like this too because of them.” Since the fighting intensified, some 3,000 Lebanese, both civilians and combatants, reportedly have been killed in the Israeli campaign.

Eman Siback lives in the northern Arab town of Shfaram, which like most others has no bomb shelters. She and her husband seek safety in their bedroom, surrounded by other rooms, making it the most secure spot in their home. The town is mourning for a mother and son who went out to harvest olives last week and were killed by rocket fire.

“It shows we are all in the same situation whether we are Arab, Jewish, Druze, young, old, male, or female,” she says. “We are all in the same boat, and it feels like things are only deteriorating.”

Trump prepares for ‘economic warfare’ with China

President-elect Donald Trump is planning a trade war with China, and Beijing is considering its options. Sitting back and accepting tariffs does not appear to be among them.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

Laurent Belsie Staff writer

President-elect Donald Trump said often during his election campaign that the word “tariff” was “the most beautiful word in the dictionary.” He was talking about trade tariffs, the protectionist taxes that governments can impose on imports to reduce their trade deficits.

Traditionally, the United States has pursued an aggressively free-trade policy, and most economists say it has benefited from that. But Mr. Trump has other ideas, and he has particularly set his sights on China. America’s trade deficit with the Asian giant has quadrupled since China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001.

The incoming U.S. president says he will slap 60% tariffs on Chinese imports in a bid to balance the trade figures, but there are doubts that this policy will have the desired effect. Mr. Trump waged a trade war with China during his first term, and China fought back with its own tariffs.

Imports fell on both sides of the Pacific, slowing economic growth, and U.S. consumers paid higher prices for items manufactured with Chinese products.

This time around, China is ready to retaliate again against U.S. tariffs. It remains to be seen what weapons they choose to employ, and how long the coming trade war will last.

Trump prepares for ‘economic warfare’ with China

At a recent Harvard University lecture, former Trump administration trade representative, Ambassador Robert Lighthizer, grasped the podium and pitched his urgent imperative for U.S. policy toward China.

“We must continue to strategically decouple our economy” from China, the trade lawyer told the student audience. “This,” he stressed in his raspy voice, “is the key economic policy battle of patriotic Americans in the upcoming generation.”

Today, Mr. Lighthizer is widely seen as the man who will mastermind the incoming Trump administration’s trade policy. And he is preparing to advance his plan to pry apart the world’s two largest economies – with vast and uncertain impacts on global commerce.

Behind this aim are iconoclastic, protectionist views that break with decades of mainstream U.S. free-trade doctrine. Concepts such as comparative advantage – when each country makes what it does best and everyone benefits – no longer work, the protectionists assert, because China is subsidizing its companies to the tune of billions of dollars a year.

That, argues Mr. Lighthizer, means that the United States must work to eliminate its trade deficit with China and force a trade balance between equal imports and exports. “This would stop the annual wealth transfer and ensure American money is not disproportionately padding the profits of Chinese companies,” he told his Harvard audience.

The overarching goal is a broader and more lasting reordering of the world trade system than took place during Mr. Trump’s first term. It would involve more curbs on the outflow of U.S. technology and investment, as well as steeper trade tariffs. Toward that end, Mr. Trump and Mr. Lighthizer have endorsed the extreme step of ending China’s favorable trade status – called “permanent normal trade relations” (PNTR) – with the United States.

“We’re headed for a pretty full-on battle in the first few months” of the Trump administration, says Arthur Kroeber, head of research at Gavekal Research and author of “China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs To Know.”

If Mr. Lighthizer is paving the way for Congress to revoke China’s PNTR status, Mr. Kroeber says, “that is pretty much a declaration of economic warfare.”

Are trade deficits really so bad?

The United States’ goods trade deficit with China has ballooned since China was awarded PNTR by the U.S. in 2000 and joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. It soared from $80 billion in 2001 to $367 billion in 2022, contributing to heavy job losses in U.S. factories.

Today, officials in the United States, Europe, and around the world are warning of more China shocks as Beijing’s top-down industrial policy favors the country’s high-tech manufacturing sector. This leads Beijing to overproduce goods such as electric vehicles and green energy equipment, making far more than its domestic consumers buy.

Overall, “China accounts for 30% of global manufacturing, but only 18% of consumption,” says Scott Kennedy, a researcher with the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington-based think tank.

But that’s not the whole story, and trade deficits aren’t necessarily bad, some American economists say.

“When a plant closes, everybody says, ‘Ah hah, this is China,’” says Mary Lovely, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. But cheap Chinese products have also kept prices low for American consumers and helped companies such as Apple create jobs in the United States, she says. “A lot of the gains from engaging with China just weren’t seen.”

Indeed, the complex reality of U.S.-China trade is clear from Mr. Trump’s first trade war, launched in 2018, when his administration imposed 25% duties on $34 billion worth of Chinese imports. China retaliated with tit-for-tat tariffs. By the height of the trade war, in September 2019, three-quarters of Chinese imports to the U.S. carried new tariffs, averaging nearly 21%, which President Biden largely maintained. And China had slapped new tariffs averaging nearly 17% on two-thirds of U.S. imports.

The result? Imports on both sides have fallen, slowing economic growth for both the United States and China. Chinese exports to America, made more expensive by tariffs, have fallen by roughly a fifth, and U.S. consumers paid for those tariffs in the form of higher prices.

And one 2024 study found that tariffs on Chinese goods actually reduced the number of U.S. manufacturing jobs by 2.7%. That’s because the 0.4% jobs boost from protectionism was swamped by job losses associated with rising input costs and retaliatory tariffs.

Can a martial arts expert beat a brawler?

On the campaign trail, Mr. Trump called tariffs “the most beautiful word in the dictionary,” proposing duties as high as 60% on Chinese goods, and 10% to 20% on all other imports. He has promised that such tariffs will help create jobs by bringing manufacturing back to the United States.

But the risk of significant damage to the U.S. economy – and political fallout – could constrain the Trump administration, some experts say.

Such massive tariffs could significantly raise prices in the United States, hurting American businesses and consumers alike. One study estimates that a 10% tariff would act like an annual consumption tax increase of about $1,500 per U.S. household. That would be “quite inflationary, and will get in the way of the reindustrialization of the U.S.” says Mr. Kroeber.

Beijing’s scope for tariffs of its own is more limited than America’s, given that China imported $147 billion in American goods and exported $427 billion worth of goods to the U.S. in 2023.

But China could use tariffs to inflict political damage on Mr. Trump in sensitive areas – perhaps targeting U.S. agricultural products so as to hurt American farmers, Dr. Lovely says.

Or Beijing could let its currency weaken, making its exports cheaper. Or the authorities could step up export controls, curbing sales of graphite to the United States, for example. Graphite is essential to making batteries for electric vehicles, and China is the world’s top producer.

Chinese experts have voiced confidence that China could cope with Washington’s reversion to protectionism. A prominent nationalist scholar quoted in the blog Sinification was dismissive.

President-elect Trump “is a turtle boxer,” meaning a brawler, Jin Canrong, a prominent analyst of U.S. affairs, was quoted as saying. “He has no stamina,” unlike a skilled martial artist. “You just need to withstand the first wave.”

A deeper look

Women in construction find solidarity as ‘sisters in the brotherhood’

As more women enter skilled construction trades, they are laying a foundation to succeed in a rough-and-tumble world of labor union brotherhoods.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 15 Min. )

-

By Richard Mertens Special contributor

-

Riley Robinson Staff photographer

When Isis Harris landed a job as an apprentice electrician in 2014, it meant far more than just finding well-paying work. It was a lifeline of sorts, a path to empowerment and independence, she says.

She grew up in northeast Portland, Oregon. After her mother died, she was raised by an aunt, and then lived in foster homes as a teenager. She had a child and dropped out of high school. “I was working in 10 jobs, just trying to make something stick,” she says.

Then Ms. Harris entered a construction preapprenticeship program for disadvantaged groups. “The electrical trade was the one that spoke to me,” she says.

Skilled laborers like Ms. Harris, as well as a number of trade unions, often refer to women on the job as “sisters in the brotherhood.” The number of women in skilled trades has doubled over the past decade, though numbers remain small. In 2023, only 2.9% of electricians were women. In other trades, 3.1% of carpenters and 2.2% of plumbers were women last year.

“[Until] our numbers grow, we will continue to push for more women on the job,” says Lisa Lujano, a 25-year veteran carpenter in Chicago. “It’s a slow journey, but it’s going.”

Women in construction find solidarity as ‘sisters in the brotherhood’

Last year, Lisa Lujano, a longtime member of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners Local 54, found herself in very unfamiliar company.

She had been tasked to build stairs in one section of the Obama Presidential Center on Chicago’s South Side. When she showed up for work, she discovered she would be part of a crew of five, all women.

“I don’t know how it came about,” Ms. Lujano says. “I don’t know if it was good intentions or bad intentions – keep all the women together. But all of a sudden, it was all girls.”

Most of the time, when she shows up for work, she’s the only woman on the crew. And she and her fellow tradeswomen know as well as anyone an inescapable truth: The American construction site is still a man’s world. Until that moment, at least, when suddenly it wasn’t.

“It was a good experience,” Ms. Lujano says, looking back on the 11 months working alongside other women carpenters. “We were able to relate, be more comfortable with each other.” Then she adds, almost exultingly, “We’re sisters in the brotherhood!”

“Sisters in the brotherhood.” It’s a phrase that resonates powerfully among American tradeswomen. It expresses not only their hard-won and deeply felt camaraderie, but also both their aspirations and their struggles as women increasingly don hard hats and tool belts and shoulder their way into the domain of American construction workers.

Ms. Lujano has been a member of her union for almost 25 years. The journeyman carpenter loves her work, the daily routine. But she still puts up with unpleasant conversations. At lunch she’ll sometimes sit by herself, or take a nap in her car. But she sees a lot of progress since she was a young apprentice a quarter of a century ago.

On a recent Friday, she was up at 5:30 a.m. at her home in Gary, Indiana. After getting ready and letting her dogs out into her yard, she got into her red Ford Escape and headed to her current job.

She’s on a team of about 60 workers rebuilding a train station at the edge of the University of Illinois Chicago campus. She’s one of only five women at the site today, the only one on her crew of 10.

Her day at the site begins with a meeting in a trailer – the conference room of construction workers. A union foreman reads aloud the job instructions for the day and the safety precautions they must take. Ms. Lujano and other workers each sign an acknowledgment.

While supervisors linger to figure out assignments, Ms. Lujano leads the workers through a few minutes of stretching in the cool morning air, which has become a morning ritual for them. She hasn’t always had this kind of rapport with her mostly male co-workers, and afterward they head to their cars to put on their gear.

Ms. Lujano wears hard-toe boots, knee protectors, and a safety harness with a steel hook. Her hard hat is pink. She also wears a thick leather belt from which hangs an assortment of tools, including a $300 titanium Stiletto hammer. She buys only the best.

Over the past decade, the number of women in the construction sector of the U.S. economy has risen steadily, from about 800,000 in 2012 to about 1.3 million in 2023, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Only 11% of jobs in construction industries are held by women, and the majority of these jobs are in office work, sales, or other support services. A growing number are even becoming managers. But on construction sites themselves, the vast majority of construction workers remain men.

In fact, the number of women in the skilled trades has doubled over the past decade. But in 2023, only 3.1% of carpenters were women, according to federal statistics. In other trades, 2.9% of electricians and 2.2% of plumbers were women last year.

“The whole process of diversifying the construction trades has been an incredible slog,” says Jayne Vellinga, executive director of Chicago Women in Trades, an organization that has worked for decades to help women find jobs in the skilled trades.

Yet even Ms. Vellinga, who says she’s “not not optimistic,” sees this as a moment of hope for women in the trades.

There’s been a surge in demand for construction workers. The federal government continues to pour money into infrastructure and other construction projects. Areas affected by recent hurricanes also need to bring in hordes of outside workers as communities begin to rebuild.

But about 94% of construction firms report being unable to hire the skilled workers they need, according to the Associated General Contractors, a trade group in Arlington, Virginia. Experts estimate this shortage numbers more than a half-million workers.

Given these shortages, the contractors trade group also found last year that 77% of construction companies report that “diversifying the current workforce at our firm is critical to strengthening our future business.”

This doesn’t mean companies will be hiring more women. There remains a significant cultural obstacle to bringing more women into and training them for the skilled trades: Construction is still widely believed to be the domain of men. As one woman who owns a large construction firm put it in an oft quoted remark, “The biggest challenge of being a woman in construction is the constant reminder that you are a woman in construction.”

From apprentice to journeyman: one woman’s unconventional path

Like many women, Ms. Lujano followed an unconventional path into the trades. She had no family connections, no uncle or father to bring her into the business, as young men often had.

She had dropped out of high school to care for a son who was just a year old. “I couldn’t support him,” she says. “I couldn’t do anything.” She needed a way forward.

In 1998, she saw a flyer from Job Corps, a federal program that offers young people preapprenticeship training and a chance to finish high school. The flyer listed different jobs: plumber, electrician, carpenter, secretary, and more.

She enrolled in a program in Golconda, a small Illinois town on the banks of the Ohio River. There, over 13 months, she earned a GED certificate and received hands-on training in how to build things. She and other students built ladders, bunk beds, and even frame houses. “It was just so cool,” she says. “I ended up loving it.”

But it wasn’t easy. In her first job she spent four months demolishing and rebuilding porches for a nonunion contractor. Then she got her first union job, working on a bridge in Skokie, just north of Chicago. She was the only woman in a crew of young men in their early 20s. The men would make vulgar comments to her, or about her, even in her presence.

“Suck it up, buttercup,” she would tell herself. “That’s the way it is.”

That was a long time ago. Ms. Lujano is no longer a rookie apprentice, but a journeyman carpenter making the full journeyman’s wage: $55 an hour, plus health benefits and a pension. She’s also a union steward, responsible for making sure the workers are properly credentialed and helping them deal with complaints or problems on the job.

The pay gap between men and women in construction, in fact, is far better than the national average. Women are paid 96 cents to every dollar men in construction industries earn, according to the National Association of Women in Construction. Overall in the United States, this gender gap is 84 cents to the dollar.

Looking out over the worksite at the train station in Chicago’s Near North Side, Ms. Lujano sees both good and bad, both progress and the limitations of that progress. Including her with the carpenters, there is one woman among the electricians, one among the ironworkers, one among the bricklayers, and one among the painters. Tradeswomen often feel they are only tokens of diversity on the job site. But to Ms. Lujano, one woman is better than none.

“I actually feel connected that there are others on the job that are like me, the only female on the crew,” she says. “It’s a good feeling to see that there are other women on the job, even though it has to be in different trades. There are times where you are the only woman on the job between all the trades.”

As more women trickle into the trades, however, efforts are expanding across the country to recruit and train more qualified women. This includes recruiting efforts in union halls to train and support more women, and the forging of regulations and labor agreements to make sure it happens.

Like many veteran tradeswomen, Ms. Lujano is part of this work. Now in her third decade as a union carpenter, she feels keenly the need to help younger women as they face the challenge of working in a world that has, for so long, been dominated by men.

“It can sometimes be irritating that the crew has room for only one woman. But until our numbers grow, we will continue to push for more women on the job. It’s a slow journey, but it’s going.”

A path to empowerment and independence

When Isis Harris landed a job as an apprentice electrician in 2014, it meant far more to her than just finding well-paying work.

It was a lifeline of sorts, a path to empowerment and independence, even salvation, she says. She grew up in northeast Portland, Oregon. Her mother died when she was 3 years old. Raised by an aunt when she was a child, she lived in foster homes as a teenager. Like the young Ms. Lujano, she had a child and dropped out of high school.

Then Ms. Harris was convicted of assault and served five years and 10 months at the Coffee Creek Correctional Facility in Wilsonville, Oregon. When she got out in 2011, she looked for work in a number of places. She was a mill tech in a steel mill, a processing and packing clerk at a paper mill, and then a customer service representative in a doctor’s office.

“I was working in 10 jobs, just trying to make something stick,” she says. “Once the background check came back, people would let me go.”

Three years after leaving prison, Ms. Harris entered a preapprenticeship program for disadvantaged groups. The program included visits to the worksites of different trades.

“The electrical trade was the one that spoke to me,” she says. By 2015, she was accepted as an apprentice in the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Local 48, in Portland.

But she was constantly reminded of being a woman in what was a man’s locker-room-like domain. “I felt like I had to protect myself a lot, from persistently inappropriate conversations,” Ms. Harris says. She found ways to cope. She wore earphones at lunchtime. She avoided the lunch trailer. She tended to work alone.

In some ways her experience in prison worked to her advantage. She had lived with prison guards for five years, and that had toughened her. “I had some exposure to being treated badly by white men, but being resilient,” she says. Still, there were times she had to retreat to the portable toilet for a cry. And when difficulties weighed too heavily on her, she took a day off.

The challenge was that she was not just a woman, but a Black woman. At the same time, however, she came to understand that workplace inhospitality arose not so much from hostility toward women or to Black people, but simply because of the tough-guy, chops-busting culture of construction.

“The construction industry is one of those industries where everyone’s kind of indoctrinated that you have to have a tough skin,” Ms. Harris says. “You have to swing with the punches. It gives people a leeway to be rough, to be tough. To not be kind.”

She’s also had many good experiences with her co-workers, however. “I’ve been on crews that were great, that had a great culture,” Ms. Harris says. “It wasn’t just an absence of offensive speech, but the ability and willingness to interact with people from a diverse background.”

It grew difficult, however, when she became pregnant. Unions have been slow to accommodate pregnant women. There was no paid leave offered at the time, and as her pregnancy progressed, she says, she “was given some pressure to stop working, the way I was showing up to work, waddling around and sometimes being in pain.”

She stuck it out until her eighth month. Today, the union contract offers 12 weeks of paid maternity leave.

Ms. Harris has set aside her hard hat and tool belt for now as she deals with a back injury. She’s still a union member, and she keeps up with the continuing education required of a union electrician. She expects to go back to the tools one day.

Her work now is teaching, organizing, and promoting women and people from other underrepresented groups in the trades. She teaches preapprenticeship classes at Portland Community College. She also serves on numerous boards and committees, including Oregon Tradeswomen and the Women’s Justice Project.

She’s also launched her own business, 3v3ryday Grind, which both sells branded construction clothing and acts as a community initiative to address social issues in her community. The name pays tribute to her three children and the “grind” that helped support them. As a part of her business, she visits high schools to talk to students about the trades.

“They’re very inquisitive,” Ms. Harris says. “They want to know more about it. There aren’t a lot of conversations about the trades, especially in inner-city schools. Historically they have not been the communities that have been recruited from.”

Unions no longer tolerate “shenanigans or bad behavior” toward women

The work of recruiting women for the building trades has a long history. In some places, it has been going on for decades. But in most areas across the U.S., there is still a long way to go as construction companies struggle to find enough workers.

“For too long a time, unions were just contented to send out the people they had, who were part of the industry,” says Robert Bruno, professor of labor and employment at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. “Those people tended to be white males with a long history of working in the trades. They didn’t have experience working with women or people of color or Latinx.”

He’s spent many years studying the composition of the American labor force, and today he sees real change. “There’s no question that the union side has done a far better job of recruiting people of color, non-English-speaking people, and women of color – recruiting them and sustaining them,” he says. Unions no longer tolerate “a lot of shenanigans or bad behavior.” At the same time, unions, to varying degrees, have developed “sophisticated and multilayered efforts” to increase diversity.

Indeed, women have made progress breaking into well-paying trade positions mainly in cities with strong unions, such as Seattle, New York, Boston, and Chicago. In much of the rest of the country, however, tradeswomen remain few and far between.

Recruiting starts young. In Seattle, the local chapter of Washington Women in Trades puts on a yearly trade show for high school students.

“We have exhibitors clamoring to be part of the show,” says Cynthia Payne, head of the branch. Two years ago, it began offering a summer camp for girls. Over three days in late July, the girls made trivets, jewelry boxes, sheet metal toolboxes, and more. “It was a huge success,” says Ms. Payne.

Unions have also been working to support women on the job. The national ironworkers union invites ironworkers to Las Vegas for weekend programs that include instruction on communicating and working with women and other underrepresented groups.

Led by the example of the ironworkers union, others have begun offering maternity leave. In some places there are programs to help aspiring tradeswomen pay for child care while they undertake training.

All this work has limits. Efforts to increase diversity tend to focus on big publicly funded projects that are subject to both public scrutiny and local politics. Infrastructure projects that receive federal money must meet diversity requirements that advocates say are rarely enforced.

Since 1978, federal rules have set a goal of 6.9% for women in federally funded projects. But advocates say that goal is rarely met. The main challenge, as they see it, is to enlist the help of unions, contractors, and government agencies to make sure it is.

Massachusetts has been a leader in this effort. A Boston city ordinance requires that 12% of hours on major building projects be worked by women. Even during the pandemic, the number of women apprentices in Boston exceeded 10%.

Elsewhere, progress is more modest. Last spring, the Illinois Department of Transportation began a program to monitor diversity in Illinois workplaces. Shining a light on actual hiring practices, advocates believe, can help make diversity goals more than just wishful thinking or good intentions.

At the same time, the recent U.S. Supreme Court decision striking down affirmative action in college admissions has cast a chill over these efforts.

“We are living in an environment right now where goals by race and gender are under threat,” says Ms. Vellinga of Chicago Women in Trades. “Affirmative action may be something of the past with this current Supreme Court. Getting anyone to raise their goals or to enforce goals is really difficult right now.”

“I’m tired but excited.” Women offer support and solidarity.

On a recent evening, Verushuka Saez showed up in a glum mood at the offices of Chicago Women in Trades. Ms. Lujano is there, too, sitting in the lobby.

They have both come to attend a union meeting with other women carpenters. Organizations like Women in Trades offer more than training and advocacy. They also give women a place to meet and organize, to find sanctuary and solidarity.

Ms. Saez is tall, strong, and reserved. She has come by motorcycle and is clad in black leather. She approaches Ms. Lujano shyly. “I got a job, but there’s a hold,” she says. It’s a common worker’s limbo: a job but no work.

Ms. Lujano commiserates. “It’s crazy out there,” she says. “Everybody’s on a hold.” Their conversation turns to motorcycling. Ms. Saez is planning to participate in a charity ride the coming weekend.

But they return to the subject of work, and Ms. Saez voices old complaints about male privilege in the industry. “You need to know someone,” she says wearily.

Her first day on the job three years ago could hardly have begun worse.

She wanted to work as a carpenter, since she discovered how much more she could make compared with the low-paying jobs she’d had. She failed the written test three times before qualifying, but she persevered and became an entry-level apprentice.

Then, on her first morning, she missed a turn and arrived late. That was something she knew from her training she must never do. “Oh my God,” she thought. “I messed up already.”

Her boss was forgiving, however. And she learned her first on-the-job lesson: Whoever shows up late must pay the next morning with coffee and doughnuts. But that first day, and the next, and for weeks afterward, she faced a more difficult test. The work wasn’t difficult, but it was a new experience for everyone, with a young Puerto Rican woman in a crew of older white men.

“It was a little intimidating,” Ms. Saez says. “Some of the guys would think I couldn’t do the job. I was a girl. Or they said, ‘Don’t worry, we can do it.’ I was treated like a little kid. It took them a couple weeks to accept that I was a worker with them.”

She’s more confident these days. But she’s found that becoming a union apprentice is no guarantee of work. She spent last winter frustrated and unemployed. Indeed, she and other tradeswomen often feel they’ve been hired to be the token woman on a job, to satisfy diversity goals.

“I feel that once you’re in, companies grab you for just a certain amount of time,” Ms. Saez says. “They take male apprentices over female.”

But both of them love the work, and Ms. Lujano, as much as any tradeswoman who’s been around for 25 years, can feel a modicum of optimism.

Back at the train station construction site near the University of Illinois Chicago, she trudges off the platform at 3 o’clock, the end of her workday.

She’s hot and sweaty, her face flushed. Still, she’s in a buoyant mood. It’s Friday. In just a week she’ll travel to New Orleans to attend a national convention of tradeswomen. And tonight she’ll meet some carpenter friends for dinner. The thought of each cheers her.

“I’m tired but excited,” Ms. Lujano says. “I’m meeting my sisters.” She adds, “I don’t do it that often.”

Books

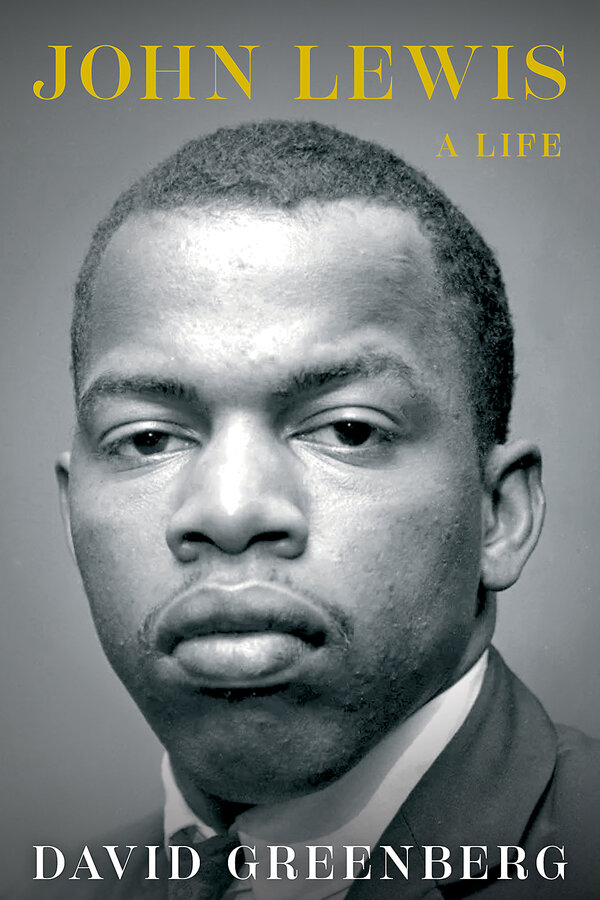

John Lewis served as ‘the conscience of the Congress’

The stories of courageous men and women fighting for civil rights in the 1960s inspire awe and gratitude. Activists like John Lewis risked their health, safety, and liberty to stand for justice.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Barbara Spindel Contributor

David Greenberg’s rich, illuminating biography, “John Lewis: A Life,” situates its subject within a lifelong commitment to nonviolent protest.

The author describes how Lewis, who went on to serve in Congress for more than 30 years, immersed himself in passive resistance while a student at the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee.

Lewis helped organize sit-ins to desegregate Nashville’s lunch counters in 1960. He was among the original Freedom Riders, the interracial group of activists that rode buses throughout the Jim Crow South in 1961 to challenge segregated interstate travel.

Greenberg crafts a vivid portrayal of his subject, featuring his “steely determination ... mixed with an unmistakable gentleness.” Jesus, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King Jr. were among Lewis’ influences. His profound commitment to nonviolence never wavered. “You have to love that person who’s hitting you,” Lewis said.

John Lewis served as ‘the conscience of the Congress’

John Lewis’ heroism is the stuff of legend. In 1965, leading 600 peaceful protesters across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, at a march for voting rights, the civil rights activist was seriously injured when state troopers attacked the procession. A photograph of him being viciously beaten by an officer shocked the United States. A week after what became known as Bloody Sunday, President Lyndon B. Johnson introduced the landmark Voting Rights Act to Congress in a televised address.

David Greenberg’s rich, illuminating biography, “John Lewis: A Life,” situates its subject’s best-known act of bravery within a lifelong commitment to nonviolent protest. The author describes how Lewis, who went on to serve in Congress for more than 30 years, immersed himself in passive resistance while a student at the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee.

His path was a difficult one. Lewis was born to sharecroppers in rural Pike County, Alabama, in 1940. His father saved up to buy his own farmland when Lewis was a child; the household, which included 10 children, had no electricity or running water. But the devout young Lewis, who famously preached to the chickens on his family’s land, was hungry to become educated and to involve himself in the civil rights struggle. Lewis, who also studied religion and philosophy at Fisk University, was the first person in his family to earn a college degree.

In Nashville, Lewis was trained in passive resistance by the Rev. James Lawson, a significant mentor. Lewis helped organize sit-ins to desegregate the city’s lunch counters in 1960. He was among the original Freedom Riders, the interracial group of activists that rode buses throughout the Jim Crow South in 1961 to challenge segregated interstate travel.

Greenberg, a professor of history and journalism at Rutgers University, crafts a vivid portrayal of his subject, featuring his “steely determination ... mixed with an unmistakable gentleness.” Jesus, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King Jr. were among Lewis’ influences. His profound commitment to nonviolence never wavered. “You have to love that person who’s hitting you,” he said.

Indeed, he had been hit – and kicked, cursed at, and spat upon – long before Selma. During the Freedom Rides, he was badly injured by a group of young men when he walked into a whites-

only waiting room in a South Carolina bus station, and he was later beaten in Montgomery by a mob. Lewis was arrested dozens of times and spent weeks in jail. He spent one birthday and one Christmas behind bars; he missed his graduation from the seminary, opting to remain jailed rather than post bail.

A founding member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Lewis became the civil rights organization’s chair in 1963. He was one of six organizers of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, along with King, with whom he had an affectionate relationship. Both men encountered resistance from a more militant faction of the movement, which began to question the efficacy of nonviolence. Additionally, within SNCC, Lewis was seen as too cozy with the establishment. “Every time LBJ called, he’d rush his clothes to the cleaners and be on the next plane to Washington,” one member griped. In 1966, Lewis was ousted as chair and replaced by the more radical Stokely Carmichael, who popularized the term Black Power. A believer in an interracial “beloved community,” Lewis was heartbroken when SNCC later voted to eject whites from the organization.

The biography is divided into two sections: “Protest” is devoted to Lewis’ participation in the Civil Rights Movement, while “Politics” covers his more than three decades representing Georgia in the U.S. House of Representatives. It’s perhaps unavoidable that the second half of the book is somewhat less gripping than the first.

Greenberg’s admiration for his subject runs deep, but he makes clear that Lewis was not a saint (despite being designated one of the “Saints Among Us” in a 1975 Time magazine article). His 1986 campaign for Congress pitted him against his dear friend Julian Bond, a fellow activist then serving in the Georgia state senate. During a debate, Lewis alluded to Bond’s rumored cocaine use. Lewis won the seat, but his friendship with Bond never recovered.

Lewis’ long congressional career was not notable for legislative achievements. Instead, his “sharpest weapon,” the author observes, “was his moral authority.” He became known as “the conscience of the Congress.” Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich grumbled that “He needs to realize that he’s now a congressman, not a protester,” but Lewis relished being both. In 1988, he was arrested for demonstrating against apartheid outside the South African embassy; in 2016, he staged a sit-in on the House floor demanding action on gun control legislation.

Lewis died in July 2020, not long after protests erupted across the nation in the wake of the killing of George Floyd. Weeks before his death, he addressed the demonstrators in a statement that captured his life’s work: “History has proven time and again that nonviolent, peaceful protest is the way to achieve the justice and equality that we all deserve.” ρ

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A graceful renewal of Notre-Dame Cathedral

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

More than five years after a fire destroyed its upper structure, Notre-Dame in Paris will reopen with grand ceremonies Dec. 7-8. The cathedral’s new bells have already been rung. A new, phoenixlike golden rooster now sits atop a rebuilt spire.

Oak trees have been hewed by hand to re-create the 300-foot-long timber roof first built by medieval craftspeople eight centuries ago. And modern artists have designed new stained-glass windows.

Yet for the thousands of people from many countries involved in the restoration of the world’s most famous Gothic church, it is not the material structure that they want visitors to notice most.

Rather, many speak of the qualities that went into their work – such as truth, joy, and humility. “For me it’s ... like nursing the injured,” worker Paul Poulet told Agnès Poirier, author of the book “Notre-Dame: The Soul of France.”

Others note how any place of worship is meant to evoke transcendent and eternal qualities. The specifications for the new windows, for example, call for evoking joy, hope, and peace. The working of the timbers and stone was done by hand because “truth comes through the genuine materials ... [and] respect for the monument as we knew it,” Philippe Jost, director of the reconstruction, told GQ magazine.

The public wants to rediscover this “refuge of beauty, tenderness, and consolation,” said Archbishop Laurent Ulrich of Paris. The project also had a healing purpose. “It shows that in this period of doubt and of questioning, if we remain united around a common goal, we can achieve the impossible,” said Olivier Ribadeau-Dumas, Notre-Dame’s rector.

The cathedral’s redone interior is a triumph “of truth and grace,” said Ms. Poirier after being allowed to step inside. Yet the ultimate grace in a cathedral revived from the ashes is the spirit of those who took a broken building and restored it. Their work was a worship of love and spiritual renewal.

A graceful renewal of Notre-Dame Cathedral

More than five years after a fire destroyed its upper structure, Notre-Dame in Paris will reopen with grand ceremonies Dec. 7-8. The cathedral’s new bells have already been rung. A new, phoenixlike golden rooster now sits atop a rebuilt spire.

Oak trees have been hewed by hand to re-create the 300-foot-long timber roof first built by medieval craftspeople eight centuries ago. And modern artists have designed new stained-glass windows.

Yet for the thousands of people from many countries involved in the restoration of the world’s most famous Gothic church, it is not the material structure that they want visitors to notice most.

Rather, many speak of the qualities that went into their work – such as truth, joy, and humility. “For me it’s ... like nursing the injured,” worker Paul Poulet told Agnès Poirier, author of the book “Notre-Dame: The Soul of France.”

Others note how any place of worship is meant to evoke transcendent and eternal qualities. The specifications for the new windows, for example, call for evoking joy, hope, and peace. The working of the timbers and stone was done by hand because “truth comes through the genuine materials ... [and] respect for the monument as we knew it,” Philippe Jost, director of the reconstruction, told GQ magazine.

The public wants to rediscover this “refuge of beauty, tenderness, and consolation,” said Archbishop Laurent Ulrich of Paris. The project also had a healing purpose. “It shows that in this period of doubt and of questioning, if we remain united around a common goal, we can achieve the impossible,” said Olivier Ribadeau-Dumas, Notre-Dame’s rector.

The cathedral’s redone interior is a triumph “of truth and grace,” said Ms. Poirier after being allowed to step inside. Yet the ultimate grace in a cathedral revived from the ashes is the spirit of those who took a broken building and restored it. Their work was a worship of love and spiritual renewal.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The elements of a truly fulfilling life

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Menganyi Moroga

Gaining an understanding that we’re the children of divine Love brings greater meaning and harmony to our work.

The elements of a truly fulfilling life

In our fast-paced world, ambition often drives our actions. Many believe that relentless striving for success is the hallmark of a fulfilling life. The Bible’s book of Proverbs certainly reinforces the value of diligent effort: “In all labour there is profit” (14:23). But are we laboring only out of a sense of obligation, or with higher motives? For instance, are we embracing our tasks as opportunities to express godly qualities?

Through my study of Christian Science, I’ve come to learn that work is about much more than just the physical and intellectual toil in our labors. It is about reflecting divine qualities such as creativity, integrity, and love. We more visibly express God’s unchanging goodness when our approach aligns with a spiritual understanding of life.

Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science, states, “Soul, or Spirit, is God, unchangeable and eternal; and man coexists with and reflects Soul, God, for man is God’s image” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 120). With this perspective, we’re more able to engage in our work and face challenges with grace rather than self-centeredness or fear.

Selfishness can distort our view of work, as well as our interactions with coworkers and clients. When we prioritize our desires above the needs of those around us, we risk fostering competition rather than collaboration. The teachings of Christian Science remind us that we are not separate entities struggling for individual gain, but rather spiritual beings unified in divine Love, which we each individually express.

As Love’s expression, our purpose transcends personal ambition. We are made to reflect God’s love, and we naturally do so in qualities such as compassion, kindness, and patience. The understanding that we are entirely spiritual removes the sense of being separate from and in competition with one another, allowing us to work in harmony with others.

In this light, selflessness is not about self-neglect but about recognizing and embracing everyone’s inherent value. By viewing ourselves and others through the lens of spiritual love and acting from that basis, we cultivate an atmosphere where everyone can thrive. This selflessness opens us to witnessing more of how everyone is expressing God. It can have a profound impact on our work environment, promoting teamwork and mutual respect and healing discordant relationships, when needed.

The teachings and example of Christ Jesus remind us that every situation can be viewed through the lens of divine Love. Christ, the divine idea of Love expressed through Jesus, shows us how to look beyond material circumstance and understand spiritual reality, where fear and limitation have no place. Jesus’ teachings give us comfort and reassurance in the knowledge that we are never separate from God’s love and guidance.

When challenges arise, we can pray and study the Bible and the writings of Mary Baker Eddy – which illumine the Bible – to gain clarity and strength. By focusing on the spiritual truths that underlie our existence, we can shift our perception from fear to faith, from resistance to acceptance of God’s behests. This shift enables us to work with confidence, knowing that God’s goodness is ever present and that we are supported in every step we take.

I experienced this firsthand working as a cybercafe attendant. My responsibilities included handling tax returns, graphic design, and data entry, and at times the sheer volume of tasks became overwhelming. I worked long hours and began to feel disconnected from any sense of purpose. It seemed as though I was simply going through the motions in order to earn a living.

Turning to prayer, I remembered that work is not just about accomplishing tasks but also about expressing God’s qualities. This shifted my perspective. I began to approach each task with a sense of gratitude, knowing that by expressing qualities such as patience and diligence in my work, I was reflecting divine Love.

As I did so, the burden lifted, and I found a renewed sense of joy and fulfillment in my daily responsibilities. What had felt like toil transformed into a labor of love, allowing me to see my work as a spiritual opportunity rather than mere obligation.

Hard work, selflessness, and love are not opposing forces but interconnected elements of a fulfilling life. By aligning our motives with the spiritual truth of our existence, we can elevate our work into a means of service that glorifies God. In doing so, we not only uplift ourselves but also contribute to the healing and betterment of our communities.

Let us work hard, not just for our own success, but to express the Love that blesses all.

Viewfinder

Never forget

A look ahead

We’re so grateful you could spend time with the Monitor Daily. We have one more story we’d like to share before sending you off into your weekend. Clara Germani looks at how experts are trying to help society rethink the vocabulary (and thought) around age and aging. You can read the story here.