The best art books lend themselves to exploration, exhilaration, and contemplation. They open you up to other cultures and eras without leaving the comfort of home. No jostling for an unobstructed view in crowded museum galleries, and no rush. You can spend hours happily turning pages or being absorbed in a single image.

These five books will transport you to early-19th-century Japan, late-19th-century England, and mid-20th-century America. They will heighten your appreciation for the magnificence of the planet’s tallest plants – and the soaring possibilities of human creativity.

Prolific Japanese master

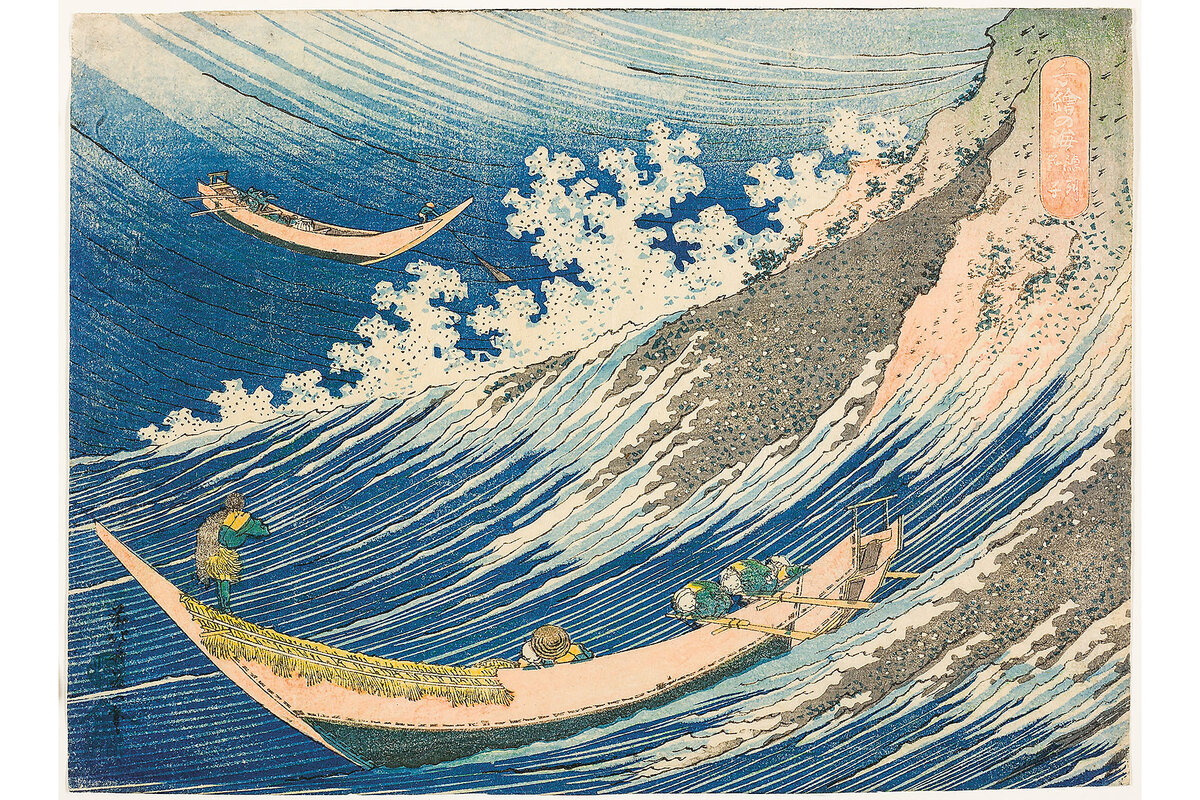

You’re going to need a big coffee table to accommodate two magnificent large-format books on the life and work of Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849). The prolific master of Edo period woodblock ukiyo-e art – “images of the floating world” – is best known for his series “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji,” but as these books demonstrate, he was proficient in other media.

Hokusai’s work, rooted in naturalism, is said to encompass some 30,000 prints, drawings, and paintings (including scrolls in ink and color on both paper and silk, book illustrations, and mass-produced copies). His subjects include landscapes, seascapes, bridges, cranes, warblers, mystical lions, and floral blossoms. He features scenes of daily life, including rituals and ceremonies, as well as portraits and caricatures of actors, poets, sumo wrestlers, courtesans, and laborers.

“Hokusai: A Life in Drawing,” published by Thames & Hudson, offers 150 detailed, full-color illustrations. Taschen’s monumental “Hokusai,” which runs to more than 700 oversize pages, encompasses a more comprehensive, chronologically arranged selection of his work.

Hokusai frequently incorporated poetry into his art, though neither book provides translations. Much of his early work featured crowds of people painted in earth tones accented by touches of pink, pale green, and burnt orange. His later, more familiar woodblock landscapes are rich in graduated shades of blue and green. One particularly alluring example depicts a group of men and women clad in blue-patterned kimonos gazing from a temple deck toward Mount Fuji.

Giving women their due

Publishers are continuing their initiative to honor long-overlooked women artists with several books this year, including “Great Women Sculptors” and the photography monograph “Consuelo Kanaga.” Particularly beguiling is “Women Pioneers of the Arts & Crafts Movement” by Karen Livingstone, which features 33 innovative women whose work helped shape British home decoration between 1880 and 1914.

Among the artists profiled are cousins Agnes and Rhoda Garrett, who co-founded the first woman’s interior design business in England in 1874 to create wallpaper, carpets, and furniture. Ethel Mary Charles, the first professional female architect in Britain, designed houses and cottages in the arts and crafts style in the early 20th century with her sister, Bessie Ada Charles. Kate Faulkner created the still-popular Mallow wallpaper design in 1879 for Morris & Co.

The range of crafts featured in the book encompasses painting, weaving, jewelry making, enamel and metalwork, bookbinding, stained glass, wood carving, and hand-painted pottery for big studios such as Minton. But many women, including those who operated the tapestry looms at Morris & Co., did not receive credit for executing the work of husbands and other collaborators. So it’s good to see Scottish artist Margaret Macdonald given her due for her significant contributions to the work of her husband, Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

Celebrating trees

“Tree,” the 10th title in Phaidon’s Explorer series, which also includes “Bird” (2021) and “Garden” (2023), offers a stunning visual survey of arboreal history in art and culture that spans continents and millennia. The sheer breadth and variety of the more than 300 images are phenomenal, with works as disparate as a 3,400-year-old Egyptian bas-relief and a 20th-century painting by David Hockney, “The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011.”

There are lovely botanical drawings of chestnut leaves by John Ruskin dating from 1870 and chestnut flowers by Mary Delany from 1776. Familiar works include Lucas Cranach the Elder’s “Adam and Eve” from about 1526 and Walker Evans’ gnarly rooted “Banyan Tree, Florida” from 1941. But there are also plenty of happy surprises and witty juxtapositions, such as Keith Haring’s “Tree of Life,” which shares a spread with Dr. Seuss’ “The Lorax.”

More sobering are several works that show the devastating effects of clear-cutting rainforests, including Niklaus Troxler’s “Dead Trees, 1992” and Jacques Jangoux’s bleak, monochromatic Amazon landscape, “Destroyed Rainforest, c. 2015.”

A handy timeline tracing the history of trees from 470 million years ago to the present strengthens this book’s compelling case for conserving these magnificent woody plants, which provide 28% of the Earth’s oxygen and absorb about 30% of carbon emissions.

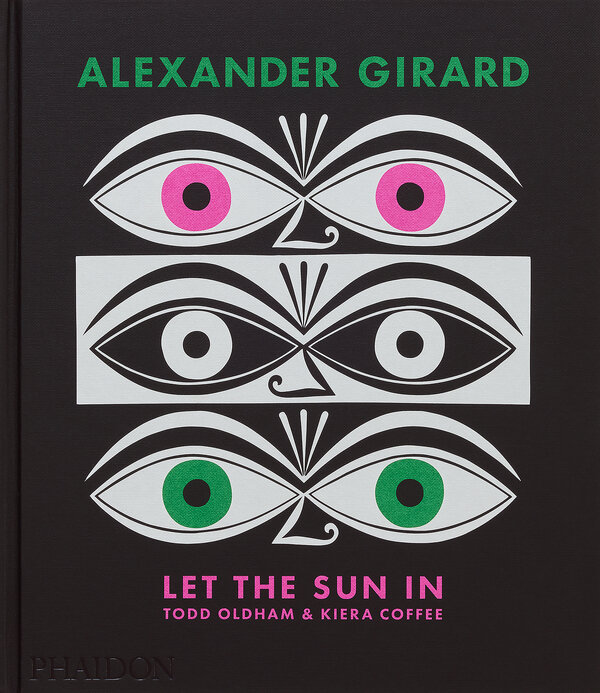

Mid-century modern geometrics

You may not recognize the name Alexander Girard (1907-1993), but if you’re a fan of mid-century modern design, chances are you’ll recognize his abstract and geometric-patterned textiles.

Highlights of Girard’s long and varied career include collaborations with Charles and Ray Eames during the years he led Herman Miller’s textile department, which still produces many of his bold designs. Concurrently, Girard created chic, modern furniture for private clients. His brightly colored, folk art-inspired design for the Latin American-themed restaurant La Fonda del Sol brought a ray of sunshine to Manhattan’s Time & Life building in 1960. In creating a distinctive new look for Braniff International Airways in 1965, Girard perked up the company’s image with a custom typeface and 56 textiles in stripes, checks, solids, and a futuristic black-and-white fabric that incorporated the airline’s new logos.

Girard is also known for his collection of folk art, which has been displayed since 1982 in a wing he designed in Santa Fe’s Museum of International Folk Art. It is impossible to capture in photographs the scale of this exhibit created to “disturb and enchant the eye.” But there’s enchantment aplenty to be found in this book.