- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- New Mideast axis rises. What do Turkey and Qatar want in Syria?

- Today’s news briefs

- Elon Musk now calls himself a ‘cultural Christian.’ What does that mean?

- Cathy McMorris Rodgers Q&A: How faith shaped her path in Congress

- With his absorbing film ‘Hard Truths,’ director Mike Leigh sees people in full

- A reporter hunts for ‘Carol of the Bells’ birthplace – in Ukraine

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

An eye on faith and religion

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

I’m excited about Sophie Hills’ story in today’s issue. One reason is that it is fascinating – a look at the growth and evolution of “cultural Christianity,” and what that says about the United States and American religion today.

But just as exciting: It is Sophie’s first story in her new role as our faith and religion writer. She’ll focus on the intersection of religion and politics, culture, and ideas. And today’s article is a great start.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

New Mideast axis rises. What do Turkey and Qatar want in Syria?

For years Turkey and Qatar backed what had been written off as the losing side in Syria’s civil war. With the Assad regime’s fall, and as Iran’s influence wanes, they are geopolitical winners. The Mideast’s axis of power is shifting, but it still runs through Syria.

Turkey and Qatar are emerging as brokers and kingmakers in Syria, filling the void left by the collapse of Iranian influence in the pivotal country and raising the prospect of a realignment of the Arab Middle East.

While they have their own ambitious interests to pursue, both see an opportunity to use Syria to revive a common regional agenda: support for popular democratic movements and Islamist political parties.

Observers say Ankara’s immediate goal is to weaken Kurdish elements in Syria, and secure a more stable military footprint. Qatar, isolated and boycotted by its Gulf Arab neighbors not long ago, is now a key Syria mediator while also facilitating Israel-Hamas ceasefire talks.

“Qatar is poised to play a crucial role in Syria’s political, diplomatic, and economic future. This involvement ... solidifies its reputation as a stabilizing force in the region,” says Ali Bakir at the Atlantic Council.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan “is a winner in the geopolitical sense because until the very end, Turkey continued to sponsor the Syrian opposition. He gambled,” says Batu Coşkun, a Turkey analyst. “Now there is an expectation [that] Turkish influence will increase,” he says, “politically, militarily, and economically.”

New Mideast axis rises. What do Turkey and Qatar want in Syria?

The Syrian people’s toppling of the Assad regime is creating a new axis of power in the Middle East.

After years in which Turkey and Qatar backed what had been written off as the losing side in Syria’s civil war, the two nations are now geopolitical winners, filling the void left by the collapse of Iranian influence in the pivotal country.

Their sudden emergence as brokers and kingmakers in Syria raises the prospect of a realignment of the Arab Middle East.

Turkey and Qatar have their own specific and ambitious interests to pursue in Syria, analysts say. At the same time, both see an opportunity to use Syria to revive a common regional agenda: support for popular democratic movements and Islamist political parties.

Since the fall of Bashar al-Assad, Turkey and Qatar have been the most active foreign governments in Syria: Turkish intelligence chief İbrahim Kalın was in Damascus Friday; a Qatari government delegation visited the capital Sunday and reopened its embassy Tuesday.

At a gathering in Doha last week with the foreign ministers of Iran and Russia, the main outside backers of the crumbled Assad regime, the Turkish and Qatari foreign ministers worked behind the scenes to ensure a bloodless transition of power.

In Doha and later in a meeting in Aqaba, Jordan, it was Turkey and Qatar that Arab states, the United States, the European Union, and the United Nations relied on to reach out to the interim Syrian government.

They were well positioned. Only weeks before, as Arab states were moving to normalize ties with Syria and calls were growing in Washington to lift sanctions on the Assad regime, Turkey and Qatar were the last two countries supporting the Syrian opposition.

Qatar was the only nation that recognized the opposition as the legitimate Syrian government. The opposition ran an embassy in Doha.

Turkey, which allowed members of the Syrian opposition to operate in exile on Turkish soil, for years maintained contacts with the Islamist Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the dominant rebel group that led the advance on Damascus, due to its military presence in northern Syria.

Strategic gains

Although Turkey denies planning the operation that overthrew Mr. Assad, once it was underway Ankara worked intensely with HTS and other rebel forces, including the Turkey-backed Syrian National Army, “to ensure it was conducted in the most bloodless, problem-free, and cost-effective way possible,” according to Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan.

“Clearly [Turkish President Recep Tayyip] Erdoğan is a winner in the geopolitical sense because until the very end, Turkey continued to sponsor the Syrian opposition. He gambled,” says Batu Coşkun, a Turkey analyst and nonresident fellow at the United Arab Emirates-based Trends Research and Advisory.

Opening Turkey up to millions of Syrian refugees had begun to hurt Mr. Erdoğan’s party at the polls. “Now there is an expectation Syrian refugees will return and Turkish influence will increase,” Mr. Coşkun says, “politically, militarily, and economically.”

Qatar, meanwhile, which was isolated and boycotted by its Gulf Arab neighbors only six years ago, is now a key mediator for the interim Syrian government while also facilitating Israel-Hamas ceasefire talks.

With Mr. Assad’s ouster, Qatar is set to “elevate its status on both regional and international stages, reinforcing its image as a peacemaker and a proactive player in Middle Eastern politics,” Ali Bakir, assistant professor at Qatar University, writes in an email interview.

“Qatar is poised to play a crucial role in Syria’s political, diplomatic, and economic future,” says Dr. Bakir, who is also a senior nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative. “This involvement not only enhances Qatar’s influence within Syria but also solidifies its reputation as a stabilizing force in the region.”

National, regional goals

Turkey and Qatar are expected to use their new leverage in Syria to pursue a constellation of national and regional goals.

Observers say Ankara’s immediate goal is to weaken Kurdish elements in Syria, including the Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), an American ally that it views as a hostile terrorist movement.

Already, a U.S.-mediated truce between the Turkey-backed Syrian National Army and Kurdish forces collapsed Monday. On Tuesday Turkey was reported to be mobilizing military units at the Syrian border, raising fears of an imminent mass offensive against the SDF.

Analysts say Turkey is looking to exclude the SDF from any postwar political system and cultivate Ankara-friendly Kurdish groups to govern any future local Kurdish regions in Syria.

Key to these efforts: legalizing the military bases Turkey has established in northern Syria in recent years.

According to diplomatic sources, Turkey is negotiating lease agreements for its bases with HTS and the interim government – similar to the deals the Assad regime gave to the Russians – to avoid being declared a foreign occupying power by future Syrian governments.

Ankara’s goal is to replicate the arrangement it has in Somalia, where it holds exclusive rights to military bases and a naval presence in Somalia’s territorial waters, observers say.

Turkey had tried to establish similar military footprints in Libya and Tunisia after the Arab Spring, but failed.

“Now with Syria possibly emerging with a government friendly to Turkey, these ambitions can be realized,” says Mr. Coşkun.

Qatar, in turn, is looking to cement regional stability, prevent internal conflicts, and accelerate reconstruction in Syria.

Both Turkey and Qatar are eyeing an outsize role in Syria’s economy.

Observers and insiders say Doha and Ankara are seeking to expand their recent building of housing for thousands of displaced Syrians into larger-scale reconstruction, with Qatar providing financing and Turkey providing contractors and materials.

And both nations are expected to reactivate another agenda that unites them: the support for democratic movements and Islamists.

In the years following the 2011 Arab Spring, Ankara and Doha backed popular protests and Islamist parties. Their efforts ignited blowback from other Gulf monarchies, who doubled down on their support for counterrevolutionary authoritarians, eventually reversing the Arab Spring’s democratic gains.

This time, analysts and insiders say, Turkey and Qatar, wary of reigniting proxy conflicts in Syria, will not seek to export calls for democracy to other Arab states. Instead they will try to shore up Syria’s democratic transition to hold it up as a regional model – to lead by example.

“Syria is a new experiment to support popular mobilization,” says Mr. Coşkun. “With a more popular movement taking charge in Syria, it is an opportunity to show this is a feasible option.”

Leading by consensus?

Already Turkey and Qatar have avoided Iran’s pitfall in Syria; instead of edging other powers out, they are inviting them in and pledging cooperation to ensure Syria’s success.

To allay concerns, they are reaching out and involving regional actors such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, and Jordan in multiple discussions about post-Assad Syria.

In turn, these Arab nations have signaled they are comfortable with Turkey and Qatar’s influence in Damascus.

“Turkey and Qatar have been inclusive and have taken into account Arab states’ concerns,” such as counterterrorism, avoiding a sectarian Syrian government, and dismantling drug smuggling rings, says one senior Arab diplomat close to the talks. “If this is the way forward, it is positive for us – and it is the complete opposite of the obstinate approach by the Syrian regime and Iran.”

Turkey has attempted to address concerns of Turkish dominance in Syria.

“We do not want Iranian domination in the region, nor do we want Turkish or Arab domination,” Mr. Fidan, the foreign minister, said in an interview with Saudi network Al Hadath Sunday, adding that Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and other Arab states can come together “to solve critical problems in the region.”

“Our message is clear. The idea of domination and imperialistic ambitions must be set aside. Attempting to control other countries in the region through proxy actions or providing financial support for ulterior motives ... leads to a vicious cycle.”

News Briefs

Today’s news briefs

• Interest rate cut: The Federal Reserve cuts its key interest rate by a quarter point, its third cut this year. It expects to reduce rates more slowly next year than previously envisioned, largely because of still-elevated inflation.

• TikTok case: The Supreme Court will hear arguments in January over the constitutionality of the federal law that could ban TikTok in the United States if its Chinese parent company doesn’t sell.

• Gaetz ethics report: The House Ethics Committee voted in secret earlier this month to release the long-awaited ethics report into former Rep. Matt Gaetz, according to a person familiar with the vote.

• Israel-Hamas ceasefire talks: A Palestinian official says mediators had narrowed gaps on most of the clauses in an agreement, but Israel introduced conditions that Hamas rejected.

• Iran pauses hijab law: Iranian authorities have paused a new, stricter law on women’s mandatory headscarf, or hijab, an official says.

Elon Musk now calls himself a ‘cultural Christian.’ What does that mean?

Some famous atheists have now adopted the term “cultural Christian” to describe themselves. What does it mean, and how is that playing out in an increasingly secular America?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Elon Musk now calls himself a cultural Christian. He joins other prominent figures – such as scientist and “The God Delusion” author Richard Dawkins – who’ve used that phrase this year to describe themselves.

Figures like Mr. Musk and Mr. Dawkins may be realizing that societal norms they value come from religious culture, and that is prompting them to try to hold on to those norms without the religious basis for them, says Robert Royal, president of the Faith & Reason Institute.

Mr. Musk “has a kind of bellwether quality,” says Dr. Royal. “I think he senses kind of a shift in the culture when he says he’s a cultural Christian.”

As fewer Americans attend church, a space has opened between religion and spirituality. “Cultural Christian” is one of the terms people are using to define themselves in that space. And certainly, plenty of Americans decorate Christmas trees, observing a tradition rooted in Christianity, though they may not attend church.

“I don’t think there’s a problem with a cultural understanding of Christianity,” says Katie Eichler, head pastor at St. Philip’s United Methodist Church in Houston. “But if it’s not pushing us to love our neighbors, then it’s a misunderstanding of Christianity.”

Elon Musk now calls himself a ‘cultural Christian.’ What does that mean?

Elon Musk, a famous name famously associated with atheism, now calls himself a cultural Christian. He joins other prominent figures – such as scientist Richard Dawkins – who’ve used that phrase this year to describe themselves.

The term “cultural Christian” seems to exist almost exclusively online. But it’s not out of nowhere. Many people call themselves cultural Jews or cultural Catholics, for example. And lots of Americans decorate Christmas trees and gather with family on Easter, observing traditions rooted in Christianity, though they may not attend church or believe in the Christian God.

As fewer Americans attend church, a space has opened between religion and spirituality. “Cultural Christian” is one of the terms people are using to define themselves in that space. Mr. Dawkins, author of “The God Delusion” and one of the most famous atheists in Britain, this spring said that he identifies himself as a cultural Christian. It is a startling turn for a man once dubbed one of the “four horsemen” trying to bring on an atheist revolution, to now see value in the morals and traditions of a religion.

Figures like Mr. Musk and Mr. Dawkins may be realizing that societal norms they value come from religious culture, and that is prompting them to try to hold on to those norms without the religious basis for them, says Robert Royal, president of the Faith & Reason Institute.

Mr. Musk “has a kind of bellwether quality,” says Dr. Royal. “I think he senses kind of a shift in the culture when he says he’s a cultural Christian.”

Everyone has their own definition

“We’ve known for a long time that a lot more people think of themselves as Christian than participate in Christian [congregations],” says Arthur Farnsley II, a research professor of religious studies at Indiana University in Indianapolis.

“I’m pretty sure that when a Christian calls somebody else a cultural Christian, they mean, ‘You feel like all this stuff is true and important; you just don’t want to make any commitment.’ It’s a low-level insult,” says Dr. Farnsley. “But when someone smart calls themselves a cultural Christian, they mean, ‘I think this religion is an important part of Western civilization, and I like Western civilization. I just don’t believe the hard parts.’”

The United States is a little unusual in its approach to religion compared with much of the rest of the world, where religion is also a cultural force, says Mark Movsesian, a professor at St. John’s University School of Law. And since its founding, America has been heavily influenced by Protestantism.

“It just means the kind of view of, What is important is your personal relationship with God. You have to really personally take this in and believe it,” says Mr. Movsesian, director of the Mattone Center for Law and Religion. “And it’s not a matter of culture. It’s not a matter of the Christmas tree and the party with friends around the yule log. That’s not what it’s about. It’s about your personal relationship.”

In his 2012 book “Flea Market Jesus,” Dr. Farnsley wrote about vendors and their views of American institutions, especially religion. While most were “folk Bible believers,” few attended church. They held religious beliefs because it’s what their mothers and grandmothers taught them, because that’s “what good people believe.” “That’s one way to be culturally Christian,” says Dr. Farnsley.

What has been the fastest-growing religious category for years is known as the “nones,” including atheists, agnostics, and people who identify as “nothing in particular.” Among those, the number of atheists has barely changed in decades, while the number who identify as “nothing in particular” grows.

Mr. Musk said he believes Christian beliefs “result in the greatest happiness,” and suggested that the decline of religion is a driver of dropping birth rates.

For his part, Mr. Dawkins said he appreciates hymns and cathedrals.

“I like to live in a culturally Christian country, although I do not believe a single word of the Christian faith,” said Mr. Dawkins in an interview with the British radio network LBC. He said he’s also uncomfortable with the rise of Islam in the United Kingdom and sees Christianity as a bulwark.

“I’m on team Christian’s side, as far as that’s concerned,” he said.

It’s not new for political or thought leaders to invoke theology they themselves don’t necessarily believe. J. Edgar Hoover, for example, incorporated aspects of religion into his role as FBI director.

“He was kind of this version of a cultural Christian, where he believed in the importance of Christianity in the kind of fight for America, and the kind of America that he wanted,” says Sam Herrmann, a doctoral student at the University of Pennsylvania who is researching the history of evangelicalism.

Over the past 75 years, American conservative politics have been imbued with mixed theological and political statements, says Mr. Hermann. “Then there’s a culture that’s built around that, and so you get these masculine Christianities, or you get these kind of capitalist Christianities, these iterations of religion and culture and politics that come together in this trifecta.”

Mr. Herrmann, who grew up in the evangelical tradition and attended Liberty University, says he wouldn’t consider himself part of the “spiritual but not religious” category. While he doesn’t consistently engage with church in traditional ways, he still feels “within the tradition” of Christianity.

Walking away from an organizational structure, he says, is “right in line with the tradition of Protestantism. It’s a history of breaking apart from some other structure in order to kind of distinguish yourself.”

“A misunderstanding of Christianity”

Congregations aren’t necessarily composed of people who see themselves as part of a given denomination. At St. Philip’s United Methodist Church in Houston, probably a little over half the congregation members call themselves Methodist, says Katie Eichler, the head pastor. The remainder, and for the most part the younger members, were drawn to St. Philip’s for its atmosphere and community, not for its doctrine.

While Ms. Eichler doesn’t hear people using the term “cultural Christian” in her congregation, some might fall into that category and might attend church more out of a sense of family obligation, she says.

“I don’t think there’s a problem with a cultural understanding of Christianity,” says Ms. Eichler. “But if it’s not pushing us to love our neighbors, then it’s a misunderstanding of Christianity.”

Many other Christians share the view that faith must be demonstrated. “When people say they’re cultural Christians, I think they’re struggling to practice it on a daily basis,” says Brian Bakke, who has worked in Southern Baptist ministry.

Though Mr. Bakke, who lives in Washington, D.C., attended a Southern Baptist church for years, he didn’t consider himself part of the denomination. Today, he’s disheartened by what he sees as a failure by the church to back up words with actions.

“There’s this powerful movement, and it comes in cycles, where in order to be a Christian, you have to separate yourself from the world – by that I mean all secular stuff,” he says. In many cases, that results in people having “no idea how to talk to their neighbors, who might be secular.”

Ways of engaging

“I might consider myself a cultural Catholic,” says Linda Serepca, director of the Charlotte Spirituality Center in North Carolina. While she might not attend weekly Mass, there are elements of Catholicism she holds “very dear,” such as liturgical seasons. “It’s the culture by which I was formed and still hold reverence for.”

While in the past identifying as a cultural Christian might have been an indication that someone was disengaging from organized religion, it now might suggest a step back toward it, says Dr. Royal.

“A lot of people who are feeling that something is wrong in the culture may not be quite ready yet themselves to confess some religion, and they may never,” says Dr. Royal, who is Catholic. “But they do detect that there’s something that came out of our tradition.”

Q&A

Cathy McMorris Rodgers Q&A: How faith shaped her path in Congress

Religiosity among the U.S. public is falling, yet Congress remains steeped in spiritual traditions. One longtime congresswoman speaks about how her faith informed her two decades in politics.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Over her 20 years in Congress, Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers of eastern Washington has risen to hold key positions as a GOP leader. She credits her Christian faith with forging that path.

During her time in office, religious worship has declined in the U.S. and there’s controversy surrounding the role of religion in public life. Yet prayer remains a prominent part of the daily bustle in Congress.

In an interview, Chair McMorris Rodgers offers a window into how faith shapes her daily work as a member of Congress – from running high-stakes hearings to overcoming rancor among members.

One key lesson she learned was from her Jewish chief of staff, who helped her understand that the days leading up to Yom Kippur are days to get right with God and each other.

“Sometimes I feel like we need that on Capitol Hill. We need a time when we ask forgiveness,” she says. “None of us are perfect. This is the United States of America, where the preamble says, ‘We the People ... in Order to form a more perfect Union ...’ That search continues.”

Cathy McMorris Rodgers Q&A: How faith shaped her path in Congress

Twenty years ago, Cathy McMorris Rodgers of eastern Washington became the 200th woman elected to Congress. She has since risen to become chair of the House Republican Conference from 2012 to 2018 and the first female chair of the powerful Energy and Commerce Committee.

Representative McMorris Rodgers is retiring from Congress next month. In a special gathering on the House floor last week, many of her colleagues cited her Christian faith as a key part of her influence and impact on the Hill.

During her time in office, religious worship has declined in the United States, with only a third of the country now attending church regularly. There’s also controversy surrounding the role of religion in public life and politics.

Yet prayer remains a prominent part of the daily bustle in Congress. Both the House and Senate open with prayers from their respective chaplains, members pray with each other and with constituents, and Congress annually hosts the National Prayer Breakfast. Some 88% of members are Christian, compared with 63% of the general population; 6% are Jewish, compared with less than 3% of the general population; and there are a handful of Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, and otherwise affiliated members.

In an interview conducted in her office, Representative McMorris Rodgers offers a window into how faith shapes her daily work as a member of Congress. A foundational Bible verse for her tenure has been Proverbs 3:5, 6 – “Lean not on your own understanding; In all your ways acknowledge Him, And He shall direct your paths.”

Her comments have been condensed and edited for clarity.

What Scripture did you read this morning?

For the last six or seven years, I’ve been reading through the Bible in a year. [This morning] I read [from] Amos and Revelation. And then a psalm and a proverb.

It’s really the spiritual discipline of reading God’s Word every day. In my time in Congress, I have found that it’s really important.

There were days when I allowed the busyness of the schedule to crowd out some of that time, and days when I might catch a devotional on the run on my app. People travel from eastern Washington to come to Washington, D.C., to pray, and they hope to have some time with me to pray as a representative. There had been times that I had told them, “Sorry, I’m too busy today.”

I’m too busy to pray? God did a work on my heart and really convicted me that I must make prayer my No. 1 priority.

I started praying more faithfully over my schedule and the meetings and the people I was going to meet. It’s been incredible to me, how I walk onto the House floor, and the members that I need to talk to [are right there] – done, done, done, done.

I never understood that [Bible] verse, His yoke is easy, His burden is light. I was like, this feels very burdened. But as you become more aware that God is directing your path, it is easier. It’s been amazing in the last 10 years, how it has been easier. And I’ve also felt like there’s been more success in the world’s eyes.

How have you approached the division and rancor on Capitol Hill?

I used to have a Jewish chief of staff for 10 years. And every year leading up to Yom Kippur, Jeremy would come to me and he would say, ‘Congresswoman, if I’ve done anything to offend you, intentional or not, would you forgive me?’ I came to learn that the days leading up to Yom Kippur on the Jewish calendar are days to get right with God and with one another.

Sometimes I feel like we need that on Capitol Hill. We need a time when we ask forgiveness. We need more grace; we need more forgiveness; we need to be seeking reconciliation. None of us are perfect. This is the United States of America, where the preamble says, “We the People ... in Order to form a more perfect Union ....” That search continues.

I think it’s really important that we continue to see God, that we continue to be the people that He wants us to be every day. And that’s why being in the Word, reading His Word and praying, is so important. Every day you get up and you thank God for His mercies that are new. And then by the end of the day, it’s like, “Oh, I fell short again. Forgive me and help me to do better.”

The March 2023 hearing that you ran with the TikTok CEO was unusually bipartisan and paved the way for legislation to end Chinese control of that platform in the U.S. How did you prepare for it?

I had the opportunity to sit down with him prior to that hearing in my office, and he said he wanted to answer any questions or any concerns that I had. After he left, I was very concerned that he obviously knows all the right things to say, but I don’t believe a word that he’s going to say. That was probably a week or so before. I really felt like there was so much on TikTok that was dark and targeting our kids in negative ways.

I needed an extra dose of wisdom and strength and courage to face it and to take it on in that hearing. We went in and we prayed before the hearing.

And it was one of those that both sides of the aisle were asking questions, raising concerns. This was not a partisan issue. Republicans and Democrats were concerned about activities on TikTok, what the real purpose of TikTok is here in the United States of America, and why it’s different here and in China, and data not being protected.

Did you feel like you were able to uncover some things in the hearing that didn’t get uncovered in your meeting with him?

Yes, and that hearing – I mean, it was one of those hearings. Everyone was talking about that hearing right here on Capitol Hill. Everyone was like, ‘Oh, you guys just really crushed it.’ And then I flew home and my staffer was showing me these clips basically making members of Congress out to be fools. I was very disturbed.

He had done a couple of videos – the CEO. And his videos went viral way beyond any reach that we had in that committee room. And I was like, wow, this is ... a big battle.

Then we worked a year before we had a vote. It was very hard to write legislation, and we had lots of constitutional attorneys helping us, multiple committees involved, working with the House and Senate.

When we brought that bill up for a vote again, some of the members of the committee went into the committee hearing room, and we prayed before the vote. And it was interesting, because one of the things I remember we prayed was that the enemy would be confused and that there would be a spirit of truth.

And the next morning, when we woke up, TikTok had blocked their 177 million users from accessing the app until they called their member of Congress and urged them to vote no.

And the switchboard, you had these kids calling, like, “I don’t even know who you are, but I gotta get on TikTok.” I mean, there were kids that were desperate. It was really sad.

The enemy was confused. It was a glimpse of how TikTok users could be manipulated. So we went into the markup that day, and it passed out of committee 50-0 at a time when most people talk about how the rancor and division make it difficult to get anything done. Republicans and Democrats came together to protect our kids and protect this nation from a tool of the Chinese Communist Party.

Mike Johnson faced a lot of critical coverage digging into his Christian beliefs after being elected speaker of the House last fall. How has he navigated that?

When I nominated him, I talked about him having the heart and the mind for the job. I used the [biblical] reference, “Man looks on the outward appearance, but God looks on the heart.” That’s what I see in Speaker Mike Johnson, is that men will look at other things or make accusations, but God looks at the heart.

There’s a verse in Psalms, Psalm 77:19, that I have shared with him as encouragement. It talks about the path through the mighty waters, the path no one knew was there, and that God’s going to direct his path. It could be very different than any other speaker of the House, but keep following God’s direction and prompting in your heart.

Film

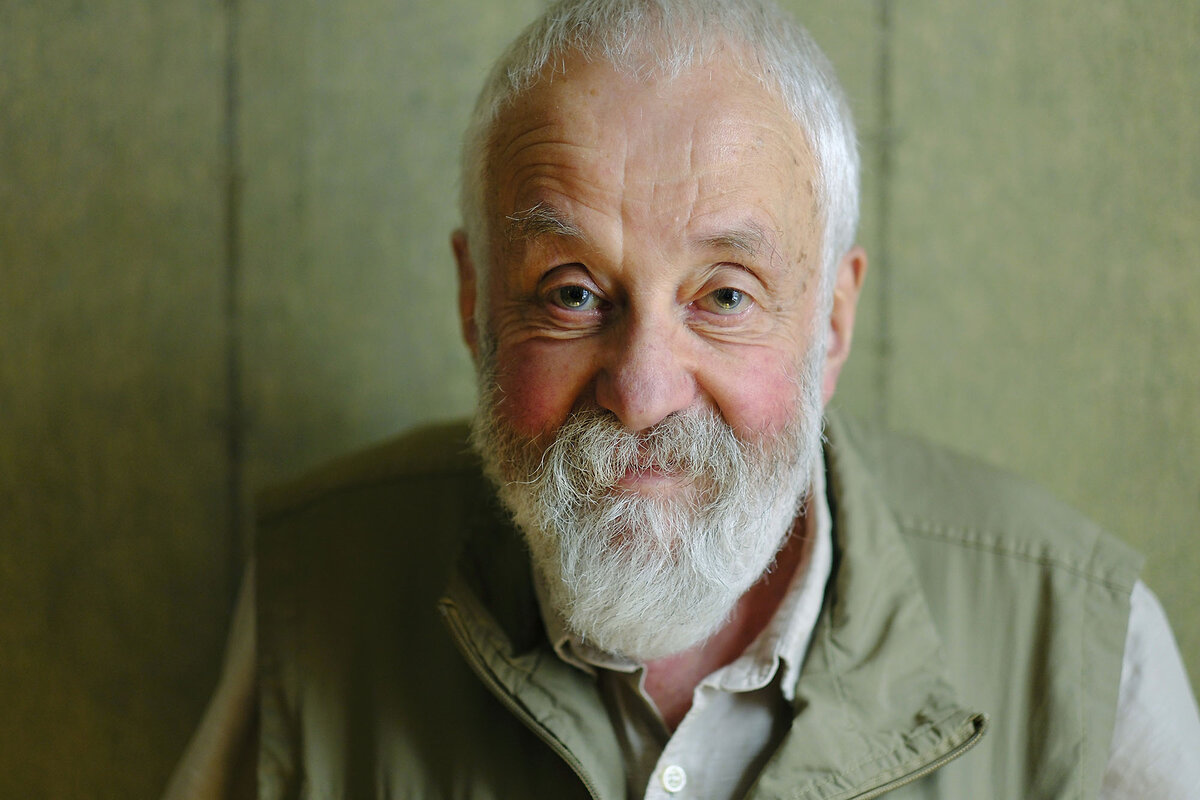

With his absorbing film ‘Hard Truths,’ director Mike Leigh sees people in full

“Hard Truths” is one of our critic’s picks for 10 best films of the year. Its director “knows that how we present ourselves to others does not always express who we really are,” he writes. “This gift, this humanism, is particularly pertinent to his fine new film.”

With his absorbing film ‘Hard Truths,’ director Mike Leigh sees people in full

Mike Leigh sees people in full. He knows that how we present ourselves to others does not always express who we really are. He literally takes nothing at face value. This gift, this humanism, is particularly pertinent to his fine new film, “Hard Truths,” because its central character is someone who often behaves unconscionably. Leigh is certainly not endorsing such behavior. He is attempting something much more difficult: He wants to understand it.

When we first see Pansy (Marianne Jean-Baptiste), a London housewife, she wakes up screaming. In the half-darkness, alone in bed, it takes her a moment to register her whereabouts. But no sense of relief comes over her.

Leigh was right to introduce Pansy to us in this way. It sets up her divided soul. Pansy is always on a tear about something. She chastises her woebegone husband, Curtley (David Webber), for not being neater. “I’m not your servant,” she growls. Her 22-year-old son, Moses (Tuwaine Barrett), mopes in his room playing video games. “What’s your ambition?” she yells at him. Her tone is not that of a concerned mother. It’s a howl of disgust.

It soon becomes clear that Pansy only comes alive when she is at odds with the world. When she shops in a furniture store, she can’t abide seeing customers stretch out on the sofas and gets into a tiff with a saleswoman. At the supermarket, she holds up the checkout line and foments a shouting match. In a parking lot, sitting morosely in her car, she trades insults with a driver looking to take her spot. At the dentist’s office, she refuses hygienic protocols and proclaims, “I am a clean person.”

Pansy’s outbursts come so thick and fast that, for a while, we take an almost morbid pleasure in waiting for the next one. She blows up the aggravations we have all experienced and turns them into cataclysmic events. It would all be grimly funny except that we know, because of how we were introduced to her, that she is in pain. Pansy’s vehement sorrow, and her inability to fathom it, allows us to see her as more than a pathetic exemplar of comic exaggeration.

Despite her protestations, she has a yearning for family. This longing makes her awareness of what she is missing all the more poignant. In the rare moments when she is not on the attack, she shuts down and goes nearly mute. Her husband and son barely speak with her – they are afraid to set her off. But her sister, Chantelle (beautifully played by Michele Austin), who runs a beauty salon, indulges Pansy’s moods because it is clear that, despite everything, they are close. A scene in which the two of them visit their mother’s grave resonates with sisterly regrets. Pansy contradicts Chantelle’s recollections of being close to their mum. “Your memory is not mine,” she says.

After the cemetery excursion, Chantelle brings her reluctant sister, and Curtley and Moses, to a Mother’s Day meal at her flat, where she lives with her two bubbly daughters (Ani Nelson and Sophia Brown). Pansy can’t accept their good graces. She thinks everybody hates her, but doesn’t make a scene. Her silence in itself is a cause for concern. Taking Pansy aside in another room, Chantelle asks her, “Why can’t you enjoy life?” Pansy says she doesn’t know why, and it’s the truest thing she says in the movie. Chantelle’s next words to her are like a consecration: “I love you. I don’t understand you, but I love you.”

It would be too convenient, I think, to write this movie off as a study of untreated mental illness. The performance of Jean-Baptiste (who was so memorable in Leigh’s “Secrets & Lies”) transcends the clinical. She shows us what lies beneath Pansy’s suffering. This woman who can’t abide other people is terrified of being alone. Jean-Baptiste and Leigh have the utmost compassion for what Pansy is going through. Extreme as she is, we can see ourselves in her. A lesser movie would have tidied things up at the end, but Leigh is too much of an artist for that. He recognizes that in matters of the heart, and of the mind, easy resolutions are few.

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “Hard Truths” opens in limited release Dec. 20, and goes wide Jan. 10, 2025. It is rated R for language.

A reporter hunts for ‘Carol of the Bells’ birthplace – in Ukraine

Over a century ago at a historical moment similar to today’s, a Ukrainian choirmaster composed a piece of music that became an iconic Christmas carol. Using an old photograph, our writer sought out its birthplace in the besieged city of Pokrovsk.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Finding the low-slung, whitewashed brick building in Pokrovsk felt like a revelation. It looked nondescript, but it was here in 1914 that Mykola Leontovych, a Ukrainian ethnomusicologist, composed and practiced a new song with the men's choral group he directed.

In Ukrainian, it is titled “Shchedryk.” You and I know it as “Carol of the Bells.”

“Shchedryk” was originally a celebration of the coming of spring, rather than a Christmas carol. By 1919, the song had surged out of Pokrovsk to take the world by storm – including at Carnegie Hall, where it earned rapturous applause.

It wasn’t until American choir director Peter Wilhousky wrote new English lyrics – and a new title – in the 1930s that the song became linked to Christmas in the West.

Based largely on the international success of “Shchedryk,” Leontovych would find himself dubbed “the Ukrainian Bach.” That did not sit well with Soviet leader Josef Stalin, who could not tolerate any nationalist cultural expression. Leontovych was assassinated by Soviet security in 1921.

Now, another Russian leader has made the eradication of Ukrainian culture and identity a prime objective.

But like Leontovych in his time, Ukrainians today are asserting their culture.

A reporter hunts for ‘Carol of the Bells’ birthplace – in Ukraine

The low-slung, whitewashed brick building was almost totally obscured from public view, hidden behind a locked metal gate and an old elm tree whose branches dropped autumn leaves on its corrugated tile roof.

Nothing about the building seemed remarkable, other than perhaps the small round windows tucked up near the eaves at either end. But to me, finding it felt like a revelation.

It was in this building in 1914 that Mykola Leontovych, a Ukrainian choirmaster and ethnomusicologist, composed and practiced a new song with the railway workers’ choral group he directed. First performed a cappella by the men of the workers’ choir, the song by 1919 had surged out of the industrial town of Pokrovsk in eastern Ukraine to take the world by storm – including at Carnegie Hall, where it earned rapturous applause.

In Ukrainian, it is titled “Shchedryk.” You and I know it as “Carol of the Bells.”

“Shchedryk” was originally a celebration of the end of winter and the coming of spring, rather than a Christmas carol. It wasn’t until American choir director Peter Wilhousky wrote new English lyrics – and a new title – for Leontovych’s work in the 1930s, evoking the clanging of church bells and the pronouncements of awe-inspired angels, that it became linked to Christmas in the West.

The frenzied and fast-paced song has little in common with calm and peaceful carols like “Silent Night” and “O Little Town of Bethlehem.” Perhaps that’s because Leontovych composed his signature melody as war and revolution threatened in Europe.

As I stood just outside the modest building in an abandoned industrial zone of Pokrovsk – the booms from Russian artillery fire punctuating the silence – I closed my eyes and listened instead for the echoes of the railway choral group singing their director’s new composition. I imagined those men exhausted by a day’s labor, yet energized by the pace, exclamatory flourishes, and message of the score.

The thought that a carol we now hear repeatedly over the holiday season – on grocery store music loops, at high school winter concerts, on car radios – emerged from a modest workers’ choir meeting at this very spot filled me with awe.

As the distant sounds of Russia’s war on Ukraine continued, I also thought of how Mykola Leontovych’s story is very much the story of Ukraine today.

Based largely on the international success of “Shchedryk,” Leontovych would find himself dubbed “the Ukrainian Bach.” That did not sit well with the new leader of the nascent Soviet Union, Josef Stalin, who could not tolerate any nationalist cultural expression. The Ukrainian Bach would be assassinated by a Soviet security spy in 1921.

Today another Russian leader, intolerant of the reality of a Ukraine independent from Mother Russia, has made the eradication of Ukrainian identity a prime objective of Russia’s nearly three-year-old war on the country.

But like Leontovych in his time, Ukrainians today are reasserting their culture to find hope and strength.

Finding the song’s birthplace

As we planned a day trip to besieged, war-ravaged Pokrovsk, the Monitor’s Ukrainian fixer and translator, Oleksandr Naselenko, asked if the city’s connection to “Carol of the Bells” was of any interest. Sasha, as Oleksandr is known, reminded me that we had seen a statue honoring Leontovych during a reporting trip to Pokrovsk in May.

I was intrigued, but said we’d need more than a statue to hang the story on. Combing the web, Sasha found a fuzzy black-and-white photo of a railroad yard building where Leontovych composed his music and directed the choir.

The next day, armed with only the old photo, Google Maps, and good old journalistic perseverance, we set off. I played “Shchedryk” from my phone to set the mood.

With the war’s front line only about 10 miles away, Pokrovsk is under constant threat of Russian occupation. The city’s military administration had set a 3 p.m. curfew, so we knew we had little time.

We passed through several army checkpoints and headed for the industrial zone along the rail line serving the area’s once-vibrant coal and steel industries. The streets were mostly abandoned, the area’s Soviet-era residential blocks quiet and dark. The few people we did encounter shook their heads in response to our inquiry.

Sasha suggested we might have to give up, as the curfew was already past. But I felt we had to be close, and asked for just a few more turns down side streets toward the sprawling rail yard.

It was then that we came upon a woman who thought she might recognize the building in the photo as one down a nearby gravel street. We followed her directions, and when an otherwise unremarkable storage building with those two distinct round windows came into view, we knew we had found what we were looking for.

Mission accomplished

“Howard, we really do have to go,” Sasha said, as dusk set in and the booms of war continued. He was right to curtail my reverie, we could leave knowing we had reached our goal.

I suggested that maybe someday we could return in peaceful times to find the building had become a museum honoring Mykola Leontovych and his gift to Ukraine and to us.

And as we walked back to the car, still I heard those railway workers singing their choirmaster’s new song.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The role model for Syria’s unity

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In the days since their liberation from a dictatorship Dec. 8, Syrians have been in a cheering mood. At the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus Dec. 13, they cheered the armed Islamist group that felled the Assad regime. In many cities, groups of people cheered for themselves with the chant “Hold your head up high, you’re a free Syrian.”

Yet perhaps the most heartfelt cheer came during a Dec. 11 parade atop firetrucks and ambulances. People in the capital gave a hero’s welcome to a grassroots rescue organization widely seen as the country’s most selfless, trusted, and impartial group: the Syrian Civil Defense, otherwise known as The White Helmets.

This band of some 3,000 unarmed and local volunteers, who wear white headgear, has saved more than 129,000 people during 13 years of civil war. Even though some 10% of them have been killed, the volunteers hold fast to their motto (a verse in the Quran): “Whoever saves one life, it is as if they have saved all of humanity.”

If Syria becomes a unified and democratic country someday, the example set by The White Helmets may be one reason.

The role model for Syria’s unity

In the days since their liberation from a dictatorship Dec. 8, Syrians have been in a cheering mood. At the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus Dec. 13, they cheered the armed Islamist group that felled the Assad regime. In many cities, groups of people cheered for themselves with the chant “Hold your head up high, you’re a free Syrian.”

Yet perhaps the most heartfelt cheer came during a Dec. 11 parade atop firetrucks and ambulances. People in the capital gave a hero’s welcome to a grassroots rescue organization widely seen as the country’s most selfless, trusted, and impartial group: the Syrian Civil Defense, otherwise known as The White Helmets.

This band of some 3,000 unarmed and local volunteers, who wear white headgear, has saved more than 129,000 people during 13 years of civil war. They have rushed to bombed-out buildings to search for survivors – whether they be children, terrorists, or soldiers of the regime. After they served as first responders, they would then clear rubble, rebuild homes, and restore communities.

Even though some 10% of them have been killed, the volunteers hold fast to their motto (a verse in the Quran): “Whoever saves one life, it is as if they have saved all of humanity.”

If Syria becomes a unified and democratic country someday, the example set by The White Helmets may be one reason. Its leader, Raed Al Saleh, says the group’s neutrality and independence have been an important shield.

“We existed before all these armed groups and we continue to exist based on the power of the people,” he told Berkeley News in October.

Now The White Helmets wants to help Syrians “shake off the dust of war,” he said in a video on the social platform X. That effort includes their help in freeing political prisoners, clearing land mines, and preserving documents of the regime’s abuses. “The Syria of peace and civilization will return to you,” said Mr. Saleh.

The country still has many civil society groups that have survived the regime. “Syrians are not to the right or to the left – they are in the middle, they are just normal people,” White Helmets co-founder Abdulrahman Almawwas told Voice of America. “So we hope that the next government ... will lead us to a new Syria that all Syrians dream of.”

That dream was heard in the public cheers for The White Helmets, whose willingness to save all people has laid a foundation for a country too long torn apart by war over religion, ethnicity, and geopolitics.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

What is our purpose?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Gabriella Horbaty-Byrd

As we lean on God for our direction, we discover our spiritual purpose, a clear path forward, and deeper satisfaction.

What is our purpose?

What is our purpose?

That’s a question that I struggled with growing up. I felt my purpose was defined mostly by external factors, such as meaningful work, the right relationships, and a nice home. And if any one of these things was lacking, I would feel discouraged and without a clear sense of self-worth or direction. I would then put a lot of effort into finding, or trying to reestablish, what I thought was missing in my life. This approach brought a lot of disappointment and frustration.

Later, through my study of Christian Science, I learned that we can discover our purpose by looking “deep into realism instead of accepting only the outward sense of things” (Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 129). I understood this to mean that we look to an understanding of God and our individual relation to Him.

We are God’s creation and, as such, express qualities such as peace, harmony, clarity of thought, and joy. These qualities always find their right expression in our work, our homes, our relationships, and our communities. They constitute our completely spiritual nature as God’s children and enable us to fulfill God’s purpose for us – to reflect His goodness and harmony.

If we ever feel stuck, without a sense of meaning in what we do, or uncertain about our path forward, we can trust God’s law of progress. In Science and Health, Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, writes, “... progress is the law of God, whose law demands of us only what we can certainly fulfil” (p. 233). How wonderful to know that God’s law of progress is constant, showing us the way forward and demanding of us only what God is enabling us to do.

At one point in my life, I was living in another country and had been laid off after only a short time at a job. Deeply discouraged, I called a Christian Science practitioner to pray for me. After I had prayed for several days, the thought came to put my will aside and let God do His work.

I had been feeling certain that the career path I had outlined for myself was the best. However, with fresh, divine inspiration and humility in my heart, I felt impelled to let God guide me to where I could serve Him best. The following Bible passage was a helpful reminder: “My thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways, saith the Lord. For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways, and my thoughts than your thoughts” (Isaiah 55:8, 9). We can always trust God’s promise that His way (God’s plan for us) is higher (better) than our own.

I started each day by acknowledging that I was “about my Father’s business,” as Christ Jesus said of himself (Luke 2:49). Every moment is a holy opportunity to put God at the helm of thought and trust that He is showing us what we need to do.

Through prayer, I understood better that our purpose in life is to glorify God through expressing the qualities and talents He has given us. These qualities are part of our spiritual identity, and we can confidently expect to express them naturally and effortlessly in activities that bless both ourselves and others. We don’t have to worry, stress, or search frantically for purpose because there is just one Mind, God, and we are Mind’s expression. That’s the true spiritual identity of each of us.

These ideas were truly liberating. Soon a work opportunity I had never considered before came about naturally. I had to move to take this new job, and plans fell into place in a harmonious way.

Whenever doubt or fear suggests that we are lacking purpose, we can humbly acknowledge the God-endowed qualities we express as His creation. We glorify God in this eternal and infinite activity. There is never a dull moment in our eternal expression of God, only a constant unfoldment of good that blesses us and others.

Adapted from an article published in the Nov. 18, 2024, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

Focused on the future

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow for Ned Temko’s Patterns column. He suggests that the fall of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad could be a windfall for the region and for the West. But that will require a few key players – including the United States – to control the instinct to meddle.