- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 16 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Our most memorable Christmas gifts – and who gave them

- Today’s news briefs

- Can Syria heal? For many, Step 1 is addressing a difficult truth.

- Biden promised to transform the federal judiciary. Did he?

- Chillax! Here’s your guide to conversing through the winter holidays.

- Berlin will pay you to repair your broken vacuum

- Can ‘A Complete Unknown’ capture Bob Dylan?

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The Monitor’s gift to you

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

As this is our last Daily before Christmas, we thought we would make it something of a Christmas gift. We start with a cover story from the Weekly magazine in which staffers speak of memorable presents. A Huffy BMX bike; the wonders of the Sears Roebuck catalog; a delightful, fuzzy Mesozoic poet named Gronk.

I might have laughed a few times, even felt a tear. In other words, Merry Christmas.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Our most memorable Christmas gifts – and who gave them

For many children, Christmas morning is all about the presents. But as our writers unwrap their favorite holiday memories from childhood, something else comes into focus: the giver.

-

By Staff

“I remember one of the best gifts that my grandmother ever gave me for Christmas,” writes higher education reporter Ira Porter. “It brought me such joy. So I keep the bike to remember a feeling long lost to me, and the gift giver, who is no longer here.”

We asked a dozen Monitor writers to share memories of Christmas past, of gifts that have stayed with them through the years. The resulting essays offer windows into the childhood selves of writers that Monitor readers all know well.

Howard LaFranchi, the Monitor’s diplomacy reporter, ponders the significance of an early gift of a globe. “Did that gift from my parents reflect their observations that I was showing signs of interest in the world?” he writes. “Or was it a gift I had requested, a manifestation of my growing curiosity and the desire to know more about the world?”

Intern Editor Kendra Nordin Beato recalls her teenage self resolving to embrace a gift from her father, even though it also brought twinges of embarrassment.

“Dad eagerly searched my face for my reaction,” she writes. “A wave of compassion washed over me, and looking back, I think I grew up a little. ‘Thank you,’ I said quietly.”

Our most memorable Christmas gifts – and who gave them

“The fastest, coolest kid in the schoolyard”

I remember one of the best gifts that my grandmother ever gave me for Christmas. It was a 1987 Huffy, a BMX-style bike with a curved seat post and hard plastic seat with perforated holes.

She bought it for me because for a whole year I had no interest in the 1970s-era Schwinn that one of my neighbors gave me after I learned how to ride a bike. I rode that Schwinn with my older sister and two cousins in the neighborhood. Then older kids laughed at me, and I began to hate it.

My new Huffy was everything. It didn’t even matter that it wasn’t the Huffy Sigma, with plastic white discs covering the spokes, or the BMX model with five-spoke alloy wheels.

While riding it, I felt like I was the fastest, coolest kid in the schoolyard. I could pop a wheelie or do a sliding stop on the back brake, like a scene out of “The Goonies.”

I still have that bike. It’s in my grandma’s house – which may be about to be torn down. I keep it not simply because it’s always hard for me to say goodbye, but also because it reminds me of her.

I always made a list of big brand-name popular toys, not really knowing they asked too much of my grandmother’s budget. Huffys were cheaper versions of better BMX bikes she couldn’t afford. But she wanted to see me smile. That’s how Christmas worked in our house.

That Huffy was the surprise of my childhood. It brought me such joy. So I keep the bike to remember a feeling long lost to me, and the gift giver, who is no longer here.

– Ira Porter / Staff writer

Lyrical legacies from the Mesozoic: my stuffed poet Gronk, and his transcriber

My first stuffed animal was a handsome green dinosaur I named Federal, and we were inseparable. His neck plush and fuzzy outer shell, however, were not. So when Federal developed a rip from too much affection, Mom sent him to a farm upstate to play with the other dinosaurs.

That was a mistake, it turned out. I wasn’t really an indulged child, but you’d better believe that I demanded all subsequent critters get the full benefit of surgery.

The next Christmas there was a new dinosaur under the tree. Gronk came with a straw hat and a poem. Gronk had written the poem, of course, though Daddy typed it up. I can still remember Gronk’s opening lines:

A hundred million years before the

first of rabbits rabbitted

And long before the earliest bison

bisoned on the plain,

The world was warm and squoggy,

and was generally inhabited

By dinosaurs that grew and grew but

never had much brain.

All my stuffed animals had jobs. Frisby was a grocer. Bugle ran a messenger service. But it wasn’t until Gronk came along that it occurred to me that you could also be a writer.

Gronk wrote me a poem every Christmas for years. I still have them all, on onion-skin paper. I grew up to be someone who dashed off verses for friends and family on special occasions.

The urge to rhyme runs strong in me, and I even wrote a book of dinosaur poetry myself. I called it “The Gronk Chronicles.”

I would never have learned about the rich lyrical legacy of the Mesozoic era were it not for Gronk, and his transcriber, my dad.

But that dinosaur surely had a way with words, and his legacy now is mine. You’d better believe I still have Gronk, too.

– Murr Brewster / Special contributor

Tearing open the gift of giving

United States troops coming home after World War II were so grateful to be alive and so happy to be reunited with their families, who were equally joyful to see them return.

The eagerness to move past the darkness and chaos of war found expression in parents’ showering their children with gifts at Christmas. Commercial interests, of course, were eager to help.

The mail-order behemoth Sears, Roebuck and Co. issued a holiday toy catalog of 600-plus pages. My siblings and I took turns poring over it and making copious wish lists. We never got everything we wanted, but we were grateful for what we got.

Something was missing, though.

We kids had always dutifully given gifts to each other, in addition to the bubble bath for Mom and soap-on-a-rope for Dad. But then one year it changed for me. I suddenly got a great idea for something to give my younger brother. I was excited.

He was a nascent gearhead, and he’d joked about a name for a fictitious town car club. I knew a store at the mall had some new gizmo that could stamp a custom message on an article of clothing using heat-transfered letters.

I bought a blue cotton work shirt. Then I went to that store and had my custom message emblazoned across the back. I wrapped it up and put it under the tree. I couldn’t wait.

I don’t recall any of the gifts I got that year, but I remember every detail of the one I gave my brother. He thought it was so cool. Dad thought it was hilarious. Mom was impressed that I’d gone to such lengths. I glowed when my brother held up the shirt, which proclaimed, “Libertyville Street Freaks.”

That gift marked a major shift in my childhood. I’d felt a little of what our parents must have felt in celebrating their children with presents. I’d finally torn open the gift of giving.

– Owen Thomas / Special contributor

A special friend and a timeless gift, 50 years later

When Valerie moved in across the street, I was delighted to have another little girl to play with. Not only was she petite and cute as a button, but her family was unlike any neighbors I’d ever seen.

Her father, muscular and tattooed, surprisingly hit it off with my conservative dad. Her mother was young and pretty, and Mimi, the grandmother, lived with them, too.

Valerie had her ears pierced. I repeatedly pointed this out to my mom, only to be told I was too young. Eventually, she relented. I almost passed out in the store after the piercing. Valerie’s mom offered to help me twirl my stud earrings twice daily and showed me how to clean my tender earlobes.

One year at Christmas, Valerie and her mom came to our door with a shoebox. Thinking it was probably cookies or fudge, I was surprised to see lots of smaller tissue-wrapped gifts inside. As my mom and I began to unwrap them, we found several hand-painted ceramic ornaments in the little box. I had never seen anything so beautiful.

We laid them all out on the table and fawned. There was Santa Claus, a gingerbread house, a boy with a snowball. Others included a candy cane, Santa’s boot, and a Christmas wreath. But best of all, there was a stocking with my name, spelled correctly, which is no small feat.

It was such a lovely gift. Now married with grown children, I’ve moved several times and had many Christmas trees. And while Valerie’s family didn’t live there long, these little treasures have traveled through time with me.

Each year as I unpack our holiday decorations, I feel the same wonder I did nearly 50 years ago. When I open these ornaments, a sweet childhood memory evokes the joy of a special friend, and the delight of a timeless gift.

– Courtenay Rudzinski / Special contributor

A globe for Christmas – and a lifetime of curiosity about the world

In 1964, my big gift under the Christmas tree was a globe with robin’s-egg-blue oceans, countries in a broad spectrum of primary colors, and mountain ranges in bas-relief.

I was 10 years old.

I’ve occasionally thought about that globe, wondering why a young boy would place that atop his wish list. What did that say about a little version of me?

Here’s the chicken-and-egg question I’ve sometimes asked myself: Did that gift from my parents reflect their observations that I was showing signs of interest in the world? Or was it a gift I had requested, a manifestation of my growing curiosity and the desire to know more about the world?

I loved to accompany my parents to screenings of international travelogues – the YouTube travel documentaries of those days. They were presented on a big screen in the auditorium of the high school in my Northern California town.

I recall filling out a postage-paid postcard from a waiting room magazine. It promised a “free” book called something like “The People of the World.” Instead, it summoned an Encyclopaedia Britannica salesman to our door. My parents purchased an expensive set, it turned out. But I never received that free book.

The mountain ranges on my globe – the Sierra Nevada, closest to me; the Himalayas, so exotic! – were eventually rubbed flat.

But not my curiosity about the world. In high school, I was a foreign exchange student, living with a family in France for a year. Later I would return to attend a university.

It was a dream come true when I was named a foreign correspondent for this newspaper. Later, I was a State Department correspondent, and now I cover international diplomacy, with occasional overseas reporting thrown in. (Which explains why this tale was penned in Ukraine.)

Occasionally I wonder – did it all start with that Christmas globe?

– Howard LaFranchi / Staff writer

A gift in my parents’ closet, and a child’s rite of passage

I was around 8 years old when I discovered my parents’ secret hiding place for Christmas presents.

It was the back of my mom’s closet, a labyrinthlike cave that was deeper than it was wide. It was crammed with eccentric scarves, secondhand cotton tops, and her wedding dress in a plastic dry cleaner bag.

A few nights before Christmas that year, I got curious and went exploring. Back behind her sewing box was the gift I’d been begging for: Samantha. The American Girl doll had two long braids, an elegant plaid dress, and black patent-leather shoes. She was perfect.

On Christmas morning, as I tore open the presents addressed “from Santa Claus,” whom should I find within a large rectangular package? Samantha!

It took me a few minutes to understand. Santa was my parents. My parents were Santa. At that moment, the magic of Christmas came crashing down.

Like all kids, I managed to recover from that inevitable rite of passage. And Samantha remained one of my favorite toys for years. Still, she, too, was eventually packed away, forgotten somewhere in some closet.

A few years ago, when I had my own children, Samantha came back into my mind. During a trip to my childhood home, I searched for her in desperation. There she was, in my bedroom closet. Her hair was ratty, her tights had lost their elastic, but she still had her same cute smile. My daughters were smitten.

This year, we’ll spend our first Christmas as a family in Minnesota. My oldest is about to turn 8 years old, and, just as I did at that age, she still believes in Old Saint Nick. She told me she wanted a boy doll for Christmas, to be a companion to Samantha.

It’s unlikely my kids will rummage through my mom’s closet, digging for Christmas gold. But the power of a child’s curiosity knows no bounds. Maybe, this holiday season, history will repeat itself.

– Colette Davidson / Special correspondent

Snow monsters, turtles in a half shell, and the greatest gifts of all

When I was young, as sure as flurries shimmy through snow globe winter wonderlands, my family and I would travel to my maternal grandparents’ house for their annual Christmas party.

My favorite Christmas gift as a boy was a game wrapped in a frozen moment in time. I was either 7 or 8 years old when I received the Nintendo version of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles 2: The Arcade Game. The opening cutscene took our heroes into a burning building, and the bottom of the screen looked like a yuletide fire.

One of my most tangible memories is my older cousin and I fighting our way past endless streams of bad guys, only to succumb to an anthropomorphic mix of a polar bear and arctic wolf named Tora.

For some folks, deep cuts happen when our fingertips are sliced by wrapping paper. For others, deep cuts are remembering the names of random Ninja Turtle villains.

But the deepest cut from that time slices through my foggy memory. The North American release date of the game, Dec. 14, 1990, was only 10 days before my maternal grandfather passed on Christmas Eve that year.

Nothing was the same after that. We continued to meet as a family year after year. But after that Christmas of 1990, I had changed.

As it turned out, the most indomitable obstacle in life was not a digital snow monster, nor the greatest gift a video game. There were other gifts, other toys, other losses as I grew up. But since that Christmas morning, I discovered my grandfather and my family were the greatest gifts of all.

– Ken Makin / Special correspondent

When my father gave me a radio – and a part of who he was

Christmas 1984 was the best summer ever.

I grew up in South Africa, and seasonal celebrations in the Southern Hemisphere included invites to outdoor barbecues or a swim at the beach after we’d opened presents. Definitely no caroling renditions of “Let It Snow.”

What made that Christmas so memorable was that my father gifted me a radio. A portable Sony, only slightly bigger than my hand, with an extendable aerial. I was 11 years old, and this was the gift that introduced me to my greatest love in life: music.

My father and I were very different people. We often struggled to communicate. He was a connoisseur of classical music, and he’d amassed a formidable record collection. He didn’t get the appeal of the rock music I discovered via the airwaves.

I carried that radio with me everywhere. I even smuggled it into school. Every night, I’d listen to a DJ named Chris Prior, aka “The Rock Professor.” It was a music education. When I first heard Robert Plant’s song “Little by Little,” I didn’t know a singer could express such emotional depth.

Less than 10 years after that Christmas, my father passed away. The radio fell into disrepair. I wish my father were still here so I could tell him about the deep meaning of that gift on my life.

I’d tell him I got to interview Robert Plant, my all-time favorite artist. I’d tell him I still listen to Chris Prior’s show, just as I did when I was 11, and that I listen to it halfway around the world, via the internet, and that I regularly correspond with the DJ I’ve been listening to for 40 years.

Most importantly, I’d tell him how much I appreciate that he wanted to share the gift of music with me. Our tastes differed, but the passion was the same. That connection I now feel with my father is as invisible as the airwaves that came crackling through that radio decades ago, with an impact just as powerful. Thank you, Dad.

– Stephen Humphries / Staff writer

Teenage angst meets “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe”

In Christmas Eve 2005, I was crammed into the living room with my siblings and large extended family. My parents saved most of our gifts for Christmas morning, but my mom always picked a few for us to open the evening before. Part of the reason was to give my older relatives a chance to witness the fleeting wonder of Christmas that only a child can have.

Like any typical teenager, I was quite certain my parents couldn’t possibly understand what a mature human I had become. I expected my gifts to be as disappointing as my teenage angst.

As the paper fell to the floor from one particularly heavy gift to me, I discovered I held in my hands “The Chronicles of Narnia: The Original Novels” by C.S. Lewis.

I knew little about the series but was curious. Disney had just brought “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe” to the big screen a few weeks prior. I guess it would be nice to read the book before I saw the movie, I thought to myself. “Thanks,” I told my parents with a polite smile.

The first time I read it, I was immediately swept up into the wonders of Narnia. The whimsical characters made me laugh and cry, sometimes on the same page. Aslan, Narnia’s creator and protector, struck me with his fierce devotion, powerful presence, and tender love. His compassion felt so pure it made my heart ache, and I found myself wanting to be completely immersed in his world – a world where other imperfect young people were also trying to discover who they were, and the value they had.

As I reflect on how this gift changed my perspectives of love and life, I think about how excited I am to share it someday with my 3-year-old son and his soon-to-arrive sibling. Even as it becomes more frayed, tattered, and weathered from use, I hope they, too, will delight in this journey through a wardrobe, and to a world of self-discovery.

– Samantha Laine Perfas / Special contributor

Decades later, “She still makes me smile”

You know how people sometimes ask, “What would you grab in a fire?” My answer is always the same – my Raggedy Ann.

I don’t remember how old I was when I got her one Christmas, but I was pretty young. She was made by Larkie, my mom’s best friend, a gifted seamstress, an artist.

Larkie handmade all her gifts – including stylish outfits for my Barbie doll, outfits I still wish came in my size.

Her Raggedy Ann became my constant companion. She came with me on sleepovers and vacations. She has deep-red hair, black button eyes, a lazy smile, and a red triangle for a nose. She wore a delicate, blue-flowered dress with a white pinafore and pantaloons. But on her muslin chest is the best part: a red heart that says, “I love you.”

Both my mom and Larkie passed on decades ago. Raggedy Ann comforted me then, as well as the times when I was scared or sad. Mostly, she made me smile.

She’s a bit bedraggled now. But she hasn’t lost any of her charm, or the magical innocence of childhood. I put some of my socks over her black cloth feet to reinforce them. My friend Ali, another wonderful seamstress, sewed a new dress for her. It’s almost an exact duplicate of the original, now threadbare with age.

She sits in a place of honor on a shelf in my bedroom where I see her every day. She’s a connection to Larkie, my mom’s bestie and my second mother. She’s the embodiment of joy, and she still makes me smile.

– Melanie Stetson Freeman / Staff photographer

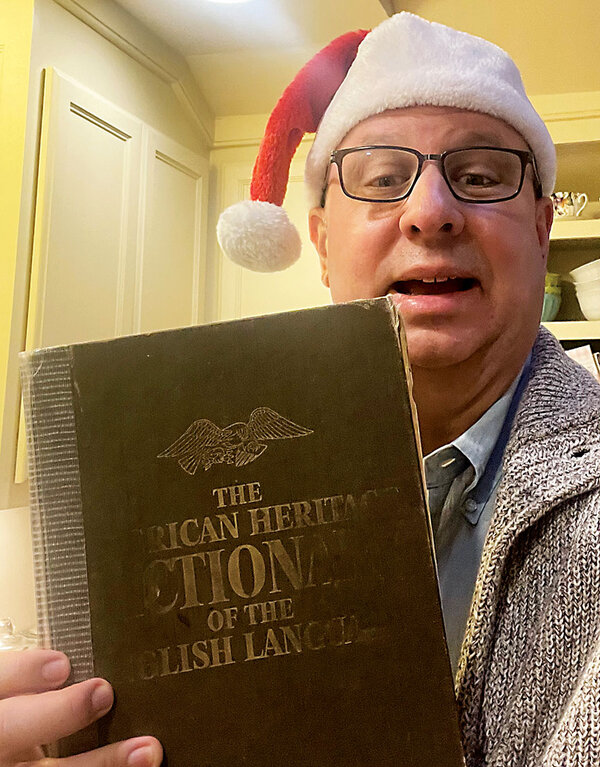

In a world of words, a gift that’s hard to define

When my Aunt Eunice gave our family a deluxe dictionary for Christmas in 1972, I didn’t jump for joy. For an 8-year-old, it seemed as exciting as a new pair of socks.

Even so, I knew Aunt Eunice meant well. She was a lively character – a longtime librarian who enjoyed travel, savored a good meal or a great story, and was thrilled by words, especially when she could arrange them for winning points during her frequent Scrabble marathons.

Language was an endless pleasure for Aunt Eunice. The dictionary she gave us, wrapped with a bright-red ribbon, was an invitation to join the fun. Before long, I was embracing our snazzy new reference volume with pride.

I loved the thumb index on the side – little tabs, arranged like stair steps, with the gold-printed alphabet descending from A to Z. There were nearly 1,500 pages in all, with entries ranging from Aachen, “a city of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany,” to zyzzyva, “any of various tropical American weevils.”

Any language with arms wide enough to touch both German cities and American weevils was something I could dwell in for a lifetime.

This year, I’ll celebrate my 60th Christmas. The toys I got on yuletides past have long since vanished beneath the snowdrifts of time. Aunt Eunice has left us, too.

But the dictionary, its binding now faded and bandaged with tape, still rests on my shelf, a constant companion through my decades as a reader and writer.

Now that online tools can quickly summon a word and its meaning, Eunice’s gift might seem outdated. But I cherish it, relishing the chance to see a vast world compressed within an intimate space.

This world of words, an infinitude of wonder, is what Aunt Eunice gave me all those Christmases ago. Even with this treasured dictionary, the gratitude I feel is hard to define.

– Danny Heitman / Special contributor

From teen embarrassment to the warmth of Dad’s gift, wrapped in love

When my family moved from Wisconsin to New Hampshire, I learned what it felt like to be new.

New Hampshire was as cold and snowy as Wisconsin, but the hills were higher. Many classmates had skied since they were 3 years old, bombing down the icy slopes. As a fifth grader, I was practically a middle-aged “flatlander” when I first peered down the ski hill, gripping my poles in terror.

The next few years, I skied by myself through the shadows of the pines to minimize the embarrassment of wiping out. By eighth grade, I was good enough to ski the most difficult trails.

There was one last thing I wanted: an L.L. Bean ski cap with earflaps and two yarn braids. All the cool ski kids had one.

On Christmas Day, my dad handed me a gift exactly the right size. I held my breath. As I pulled out a dark-blue-and-green knit cap, he said, “I had it specially made.” I paused. His eyebrows danced over his blue eyes. A self-pleased smile played across his lips.

There in my hands was indeed a ski cap with two yarn braids. Large light-blue letters marched across the forehead: KENDRA. My heart sank.

Dad eagerly searched my face for my reaction. Dad didn’t ski. Money was tight. He had tried to make something I wanted even more special. A wave of compassion washed over me, and looking back, I think I grew up a little. “Thank you,” I said quietly.

Instead of shoving it to the back of a drawer, I wore my KENDRA cap for years. I covered my name with my ski goggles under the chairlift to avoid being teased. As I flew down the hills, the cold wind streaked my cheeks in tears. But inside I was warm, wrapped in the love from my dad’s gift.

– Kendra Nordin Beato / Staff writer

News Briefs

Today’s news briefs

• Trump budget rejected: The House rejects President-elect Donald Trump’s new plan to fund federal operations and suspend the debt ceiling, a day before a possible government shutdown.

• Starbucks strike: The union representing more than 10,000 Starbucks baristas says members will strike in Los Angeles, Chicago, and Seattle for five days starting Dec. 20, citing issues over wages, staffing, and schedules.

• Biden cancels student debt: The Biden administration cancels $4.28 billion in student debt for nearly 55,000 public service workers. The action brings the total public-service student loans forgiven to about $78 billion for nearly 1.1 million workers.

• Egg prices skyrocket: Wholesale egg prices in the United States are shattering records as an outbreak of bird flu cuts supplies while shoppers buy more to bake during the holiday season.

Can Syria heal? For many, Step 1 is addressing a difficult truth.

Syrians want to learn what happened to those who were jailed or forcibly disappeared as they seek to recover from decades of a brutal dictatorship. For many, the first, difficult stop is a notorious prison.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Syria’s Sednaya prison sits on a barren hill north of Damascus, with towering brick-and-wire walls that encircle the compound like a noose. Long unbreachable, the prison doors at the terrifying complex were smashed open by rebels who overthrew President Bashar al-Assad.

Arrests and disappearances were part of the Assad regime’s modus operandi for decades. From across the country, thousands of Syrians of every generation converge here, scrambling to find any hint of what happened to missing loved ones.

Without the truth, some say, healing is impossible. But unveiling the truth is a traumatizing journey that is fueling calls for revenge.

No one is getting the answers they want at Sednaya. What they get instead is a horrifying glimpse into the inner workings of a regime propped up by fear and torture.

One young woman, Alaa, ventures toward the rooms that former Sednaya inmates describe as torture chambers. She says she has long given up hope of finding her father, who disappeared in 2015 when she was only 11 years old.

“I hope he died right away rather than spending a single second in this place,” she says. “There can be no justice for something like this. ... It is important for Syrians to know what happened.”

Can Syria heal? For many, Step 1 is addressing a difficult truth.

Syria’s Sednaya prison sits on a barren hill 19 miles north of the capital, Damascus, sealed off from the world by towering brick-and-wire walls that encircle the compound like a noose.

From across the country, thousands of Syrians of every generation converge at this spot, scrambling to find any hint of what happened to missing loved ones who were jailed or forcibly disappeared. The truth is dark and elusive, but it’s their best shot at closure, and many start their search here.

Dressed in Bedouin attire, Amash al-Farhan scrutinizes burnt and torn documents that he cannot decipher. He traveled more than 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) from Syria’s border with Iraq to Damascus looking for a sign of his son. The medical and prison logs that remain offer no promising clues.

“I thought to myself, perhaps God will deliver him back to me,” he says, gripped by emotion. “Dead or alive, the important thing is for one to know. I just want to know where he is.”

Long unbreachable, the prison doors at the terrifying complex were smashed open by rebels who overthrew President Bashar al-Assad in a multipronged military campaign that seized control of the capital.

Mr. Assad fled to Moscow, reducing the likelihood that he will face justice for the crimes committed by his regime.

A traumatizing journey

Dubbed the “slaughterhouse” by rights groups and Syrians, Sednaya is just one element in a macabre mosaic of prisons across Syria. The systemic violence of such sites explains the death and disappearance of tens of thousands of Syrians under Mr. Assad, and his father, Hafez al-Assad, before him. The quest for clarity sends men, women, and children through a labyrinth of official and unofficial detention centers.

Without the truth, some say, healing is impossible. But unveiling the truth is a traumatizing journey that is fueling calls for revenge and accountability.

It risks becoming a messy process in a low-trust society scarred by more than a decade of war that drew in foreign powers, including regional ones animated by sectarian logic. All sectors of society are affected.

Arbitrary arrests and enforced disappearances have been part of the Syrian regime’s modus operandi for decades. The Syrian Network for Human Rights blames Syrian regime forces for more than 96,000 cases of enforced disappearances since 2011, when antiregime protests erupted. Yet some families are today trying to trace disappearances that long predate the civil war.

Between tears, Mr. Farhan says his son Khaled was taken from a farm in Khan al-Sheikh, along with seven young male friends, in the Euphrates River region of Deir ez-Zor.

On what grounds? The father simply says he was “with them,” a reference to the rebels who armed themselves in self-defense after antiregime demonstrations were violently suppressed by a wide constellation of security forces and the Syrian army.

One young woman, Alaa, ventures toward the rooms that former Sednaya inmates describe as torture chambers. Wearing a puffy parka, her young face framed by a black hijab, she says she has long given up hope of finding her father, who disappeared from the Golan Heights city of Quneitra in 2015 when she was only 11 years old.

“I hope he died right away rather than spending a single second in this place,” she says. “There can be no justice for something like this. ... It is important for Syrians to know what happened.”

Nearby, Hiam, an older woman, repeats the names of her three missing sons like a mantra.

A prisoner’s story

The tales of survivors bring little comfort. Among those visiting Sednaya is Mahmoud Fakhoura, a young man wearing a red varsity sweater and sports cap, who says he survived seven years there. He says he was arrested on bogus terrorism charges for participating in the revolution.

“I never raised my head during my time in this prison,” Mr. Fakhoura says. “All I could see were military boots.”

A shell-shocked but sympathetic crowd forms around him as he recounts the hunger, beatings, and endless humiliation that he personally endured. He says he barely survived a monthslong spell in solitary confinement, fed only half an orange per day.

The crowd appeals to God as he tells of mass executions and the burning smells that followed.

No one is getting the answers they want at Sednaya. What they get instead is a horrifying glimpse into the inner workings of an authoritarian regime propped up by fear and torture, as is amply evident by equipment left behind in one prison room.

Horror at the morgue

In the capital’s largest morgue, at Damascus Hospital, the anguish of presumed loss turns to burning rage.

Visitors’ eyes widen in horror at the sight of the mutilated and emaciated bodies filling the morgue. About two dozen bodies have been brought from Sednaya and various other security facilities.

Children take in the scene in stunned silence. Mothers, sisters, and nurses cover their mouths and cry. Men vow revenge.

Abdelkarim Alshafi, who did a stint at Sednaya himself, opens cold container after container looking for five relatives who disappeared between 2013 and 2018.

“They were arbitrarily arrested in their homes and at checkpoints,” he says. “They [the regime] called us terrorists, but they are the terrorists. We ask that they be held accountable.”

Alaa al-Saadi, a native of Daraa, the southern city considered the birthplace of the 2011 popular uprising, has been looking for his brother since 2013. “There are thousands of prisoners. What did they do to them? The ones that were released are about 400 to 500. Where did the rest, the thousands, go?”

He directs some of his anger at Russia and at Shiite regional powerhouse Iran, which propped up the Assad regime. But the brunt of his rage focuses on Syria’s powerful Alawites, members of a Shiite splinter group to which the Assad family belongs. Alawites have played an outsize role in state institutions and the country’s sprawling security apparatus.

“Anyone who has honor should go after all the Alawites,” he cries, as others try to reason with him and caution against being swept up by sectarian sentiment.

“It’s my right,” he snaps back. “I lost my brother. They are criminals. What is the crime of these burnt bodies here? That they called for freedom? We don’t want Alawites in Syria at all.”

Inside the hospital, two families argue trying to prove their relationship to a disoriented young man lying on a stretcher.

A doctor settles the dispute, saying that there are no signs of the surgery cited by one of the families trying to identify him. In that same overcrowded room sit an emaciated woman with haunted eyes and an older man whose hands are mutilated. All three patients are said to have been found in Sednaya.

“I want to forget”

Families that do find their loved ones face a difficult journey of recovery.

Badly bruised, unable to stand, and weighing about 95 pounds, Wael Zaarour was just a number at Sednaya – 22789. He was moribund when rebels set Sednaya prisoners free, and is now under the watchful care of his mother in a cold and dark apartment in Homs, 100 miles north of the capital.

The arrival of strangers causes panic. Mr. Zaarour demands to see documents to ensure that foreign journalists are not agents of the recently ousted Syrian government.

“Sednaya is death,” he says later, lifting his shirt to reveal a sea of bruises on his back.

“They would tell us, you are dogs who did not deserve to eat. Killing people became a matter of habit,” he says. “There are so many things I want to forget.”

The Explainer

Biden promised to transform the federal judiciary. Did he?

Confirming a historically diverse slate of judges could be one of President Biden’s strongest legacies, but zero-sum politics continues to dominate judicial selection.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

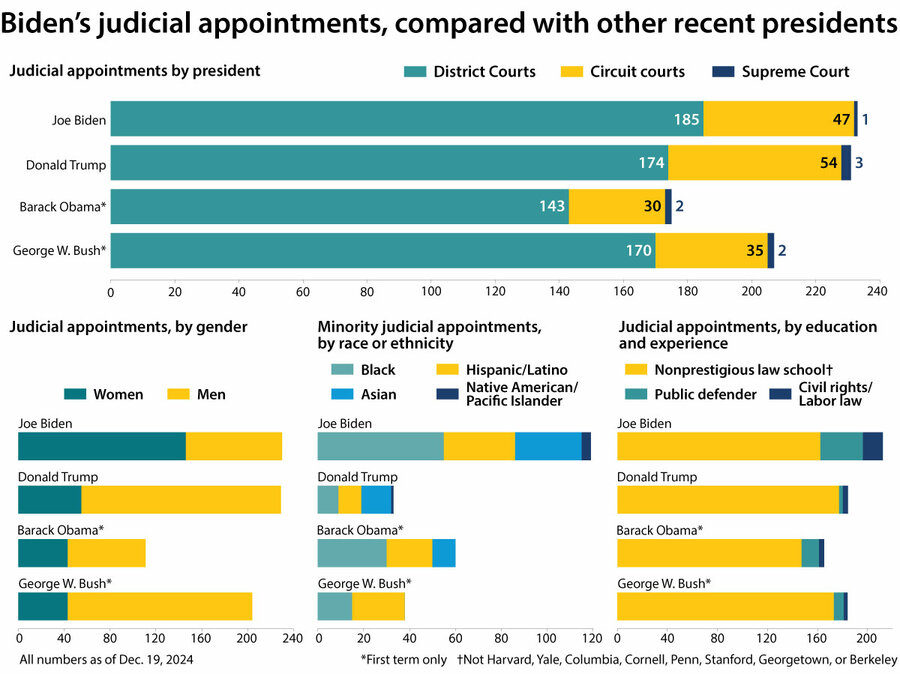

With lifetime appointments and an outsize influence on U.S. policy, appointing federal judges has become one of the most enduring ways a president can cement their legacy.

And more than any other, the Biden administration appears to have perfected this judicial confirmation machine. The result has been President Joe Biden appointing 233 federal judges, more than any one-term president since Jimmy Carter.

No president has appointed a greater proportion of women or people of color to the bench. Mr. Biden has also embraced professional diversity in his selections, nominating lawyers with experience in public defense, civil rights, and labor law to positions traditionally dominated by prosecutors and veterans of major law firms.

This legacy, however, has been secured with the help of an increasingly zero-sum political approach to judicial confirmations. Democrats “stopped being nice and started being ruthless,” says Carl Tobias, a professor at the University of Richmond School of Law. The politicization of the issue “may be more substantial than it’s ever been,” he adds. And that could come at a cost.

Biden promised to transform the federal judiciary. Did he?

As the clock ticks down on President Joe Biden’s term in office, Democrats in the United States Senate have been busy securing what could be his most enduring legacy.

Federal judges serve for life and can influence policy for decades longer than the president who appoints them. In recent years, both political parties have come to appreciate the value of appointing as many judges as possible when they control both the Senate and the White House. But more than any other, the Biden administration appears to have perfected this judicial confirmation machine.

The result has been President Biden appointing 233 federal judges, more than any one-term president since Jimmy Carter. And he has appointed perhaps the most diverse slate of federal judges in history. That legacy may have been overlooked because there were fewer openings to the coveted U.S. Supreme Court and 13 circuit courts of appeal – which have the final word on every case filed in the federal system.

No president has appointed a greater proportion of women or people of color to the bench. Mr. Biden has also embraced professional diversity in his selections, nominating lawyers with experience in public defense, civil rights, and labor law to positions traditionally dominated by prosecutors and veterans of major law firms.

This legacy, however, has been secured with the help of an increasingly zero-sum political approach to judicial confirmations. Democrats “stopped being nice and started being ruthless,” says Carl Tobias, a professor at the University of Richmond School of Law. The politicization of the issue “may be more substantial than it’s ever been,” he adds. And that could come at a cost.

What has Biden been able to do?

The Biden administration made its priorities clear early. Within 12 months of taking office, Mr. Biden had confirmed 40 judges – more than any president in their first year since Ronald Reagan. By the time Mr. Biden leaves office, over a quarter of active federal judges will be his appointees.

Mr. Biden has also been breaking new ground in terms of nominee diversity. Over 60% of his judges are women – more than any president in history – and the same proportion are people of color. No president has appointed more Black women to the federal bench, nor as many openly LGBTQ+ or Native American jurists.

Professional diversity has also been a focal point. The federal judiciary, particularly at its highest levels, had become increasingly homogeneous in recent decades, populated mostly by white men with careers in prosecutors’ offices and white-shoe law firms. Mr. Biden has appointed his fair share of prosecutors and Big Law veterans. But he has also appointed large numbers of judges with experience in other areas, such as public defense, civil rights, immigration, and labor law.

“In a democratic society, there’s an expectation that institutions will to some degree reflect the broader population, and these appointments do that,” says Gbemende Johnson, a political scientist at the University of Georgia. “They communicate that these institutions are not cut off to certain people.’’

His one appointment to the nation’s highest court embodies this push. In Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, Mr. Biden appointed the first Black woman to the Supreme Court and the first justice with experience as a public defender.

But Justice Jackson is also emblematic of the minimal impact Mr. Biden has had in reshaping the upper reaches of the federal judiciary – at least compared with his predecessor.

While Mr. Biden appointed one Supreme Court justice, former President Donald Trump appointed three. And while both men confirmed a similar number of judges to the circuit courts of appeal, Mr. Trump was able to flip more circuits to Republican-appointee majorities than Mr. Biden has for Democratic-appointee majorities.

Federal Judicial Center, Congressional Research Service

Is politicization more of an issue now?

Maybe not more of an issue, but politicization remains an issue.

Politics has played a role in judicial appointments since America's infancy, but it has ratcheted up in recent presidencies. To help Barack Obama, Senate Democrats eliminated the filibuster – a requirement that nominees receive 60 votes to be confirmed – for lower federal court judges. Senate Republicans refused to hold hearings for President Obama’s Supreme Court nominee, Merrick Garland, for almost a full year. During the Trump administration, Republican senators eliminated the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees.

GOP senators at that time also adopted an exception for circuit court nominees to the century-old “blue slip” rule, enabling them to confirm appellate judges over objections from Democratic senators from their home states. When Democrats returned to power in 2021, they kept that new rule, along with others that helped marginalize the minority party’s ability to influence judicial confirmations.

What are the consequences of political brinkmanship?

Federal judgeships have not been updated in over 30 years, leaving judges to manage “crushing” caseloads, according to the Judicial Conference of the United States. In a 2023 report, the Judicial Conference – the policymaking body for the federal court system – called on Congress to create new federal judgeships to help courts manage case backlogs.

The Senate responded by drawing up a bill that would create 66 new federal judge positions. To be fair to both parties, the new seats would be filled in tranches across three presidential administrations and six Congresses.

The bill passed the Senate unanimously in August. But it didn’t pass the Republican-controlled House of Representatives until last week, after the November election indicated that President-elect Trump would be the one to fill the first tranche of seats. The White House has said that Mr. Biden will veto the bill, and there would likely not be enough votes to override a presidential veto.

The gridlock is “one more piece of evidence of the politics of the moment,” says Christina Boyd, a professor of law and political science at Washington University in St. Louis.

“Every new seat is [viewed as] a win for the other guy in this situation,” she adds. “We’re at a place where nobody is willing to give that ground despite what I think is a real need on the ground for more judges.”

The Explainer

Chillax! Here’s your guide to conversing through the winter holidays.

As the generations gather for the holidays, communication could be a challenge. We’ve got you covered with glossaries for Generation Z and millennial slang.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

Stephen A. Smith glazed the GOAT LeBron. Timothée Chalamet rizzed Kylie Jenner with his dope smile and curls. Chappell Roan locked in at that concert and absolutely ate!

’Tis the time of year when members of multiple generations gather with their families and catch up on what’s happening in their lives and the world. But if the sentences above don’t make much sense, you might need some help ahead of your holiday get-together.

Herewith, a guide to what you might hear from millennials and Generation Zers while you eat dinner, binge holiday movies, and laze around the fireplace. (Note: Some of this slang crosses generational lines or has been borrowed from bygone eras or modern cultures. Just know that “groovy” won’t ever come back in style.)

Expand the story to see the full guide.

Chillax! Here’s your guide to conversing through the winter holidays.

Stephen A. Smith glazed the GOAT LeBron. Timothée Chalamet rizzed Kylie Jenner with his dope smile and curls. Chappell Roan locked in at that concert and absolutely ate!

’Tis the time of year when members of multiple generations gather with their families and catch up on what’s happening in their lives and the world. But if the sentences above don’t make much sense, you might need some help ahead of your holiday get-together.

Herewith, a guide to what you might hear from millennials and Generation Zers while you eat dinner, binge holiday movies, and laze around the fireplace. (Note: Some of this slang crosses generational lines or has been borrowed from bygone eras or modern cultures. Just know that “groovy” won’t ever come back in style.)

Gen Z glossary

fire, gas (adjectives): excellent; delicious. This ham is fire. And these peas are gas!

lock in (verb): to focus. Nothing ickier than yanking out turkey giblets, but I gotta lock in and take one for the team!

ate (verb): did something extremely well. I absolutely ate at the office’s winter yodeling contest!

in one’s bag: used to describe someone who pulls off something impressive. Gramps was in his bag with this gift idea. I’ve wanted heated underwear since forever!

cap (verb): to lie. That’s cap! (interjection): used to say something is false. Does this Santa suit make me look fat? Don’t cap!

high-key (adverb): used to emphasize strong feelings. We high-key despised the Grinch for stealing little Cindy Lou Who’s Christmas.

rizz (verb): to charm or woo someone (short for “charisma”). Dad rizzed Mom with one of his seasonal jokes:

Knock, knock!

Who’s there?

Freeze!

Freeze who?

Freeze, a jolly good fellow!

glaze (verb): to praise excessively. Cousin Chester’s gravy was goopy, but we glazed it anyway.

tea (noun): juicy gossip. I wanted the tea about Uncle Rupert’s messy breakup. He spilled it all in his holiday newsletter.

Millennial glossary

slay (verb): to do something very well. Granny, you really slayed this turducken!

ghost (verb): to abruptly end all communication with someone without warning; to stand up someone. We were supposed to meet under the mistletoe, but Greta ghosted me.

GOAT (noun): greatest of all time. Mom macraméd an 8-foot-tall Mrs. Claus to hang on our front door. She’s the GOAT of Christmas decorators.

salty (adjective): bitter, annoyed, disgruntled. Year after year Milo loses the ugly Christmas sweater contest. No wonder he’s salty.

glow-up (noun): a positive physical transformation. Aunt Myrtle made everyone get a glow-up for her holiday photos. No more at-home haircuts!

chillax (verb): to relax. Turkey with all the fixin’s put us in a food coma. Now it’s time to chillax in our stretchy pants and watch QVC.

dope (adjective): cool, awesome. You built a gingerbread Great Wall of China? That’s dope!

flex (verb): to show off. Whenever he has a captive audience, Felix loves to flex his collection of exotic snow globes.

extra (adjective): over the top. My family’s tradition of dressing up in matching pajamas, singing Mariah Carey songs, and watching “Home Alone” is sooo extra. But I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Happy holidays!

Berlin will pay you to repair your broken vacuum

The city of Berlin pays half the cost if you repair electronics rather than throw them away. That sounds better than it worked out in practice for our reporter.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

A sad army of broken electronics sits in my shoulder bag as I schlep through Berlin in search of my reparaturbonus – a city scheme to reimburse people up to $200 to repair stuff instead of throwing it out.

My load includes the plates on the flat iron that press frizz out of my hair and that no longer lie flat; the motor on my black household fan, which shuts off after a few minutes; the iPhone whose battery depletes itself in an instant; my journalist husband’s beloved palm-size Marantz audio recorder with a broken data-card door. (“Trust me,” I said, prying it out of his hand. “Trust Berlin.”)

The reparaturbonus offers a top payment of about $200 per device. The Berlin government has budgeted $1.3 million to try out its version of a program that has worked in other German cities as well as in Austria.

Stefan Neitzel, owner of Berlin bike services shop Fahrradstation, says: “Reparaturbonus is something that should be copied everywhere because it gives a small incentive for consumers, and for repair places, and it also might incentivize the manufacturing industry to build items that are reparable.”

Berlin will pay you to repair your broken vacuum

A sad army of broken electronics sits in my shoulder bag.

It’s a rainy fall weekday in Berlin, and I live in a city that has decided to pay people to repair stuff to reduce waste.

I mentally survey what I lug carefully across the wet cobblestones of Metzer Strasse. The plates on the flat iron that press frizz out of my hair no longer lie flat; the motor on my black household fan, which shuts off after a few minutes; the iPhone whose battery depletes itself in an instant.

Berlin’s reparaturbonus won’t be a windfall – the most it pays is about $200 per device – but I may divert a few things from the electronics graveyard.

The most valuable thing in the bag is my husband’s palm-size Marantz audio recorder. It’s both expensive and practically useless: It reads data cards only when they are held in place by an insistent finger – unfortunate for a busy broadcast journalist.

“I don’t want anyone messing with it. It’s important for my work,” my husband had said that morning, eyeing my lumpy sack of electronics, to which I’d hoped to add his out-of-production jewel. “It still works sometimes.”

I coaxed it away from him, and saw that he’d jury-rigged a rubber-band contraption to hold the data card door closed.

“Trust me,” I said, with a smirk. “Trust Berlin.”

The Berlin city government has budgeted $1.3 million to try out its version of a program this year that has worked in other German cities as well as in Austria. To anyone who fills out qualifying paperwork, it will pay back half of repair costs between $80 and $400 to fix any item on an eclectic, six-page list that includes powered toothbrushes, bread makers, table saws, and smartwatches.

The goal is to incentivize people to avoid waste and use things longer. “Reparaturbonus should be copied everywhere,” says Stefan Neitzel, owner of Berlin bike services shop Fahrradstation, “because it gives a small incentive for consumers, and for repair places, and it also might incentivize the manufacturing industry to build items that are reparable.”

The program sounds great in theory, but given my experience with Berlin – a city full of good intentions – I’m guessing it’ll be difficult to get things fixed in a decentralized repair economy and then compel a creaking German bureaucracy to reimburse me.

Repairs – potentially a boom business

Matthias Urban confirms one of my suspicions.

I’d noticed his repair shop on walks in my neighborhood. I shake off my umbrella, and step over the threshold into a brightly lit shop with warm brown laminate flooring lined with refrigerators and vacuum cleaners. Mr. Urban glances at my stuff.

“The fan – I’ll have a look at that,” he says, dismissing the other things.

Calls to Mr. Urban’s shop have increased 50% since Berlin announced the program in September. “People sometimes bring in parts they’ve sourced themselves,” he says, making me feel like a bad customer. “They’re now considering repairs rather than buying new things,” he says, nodding with satisfaction.

“The fan – leave it here. I’ll call you in a week.”

One device down, three to go. Mr. Neitzel of Fahrradstation is acting as a bit of a repair consultant, and he tells me that success will boil down to whether the part can be sourced.

“The repair industry is underdeveloped,” he says. “There’s huge demand for repair services, but success starts with good workers and ends with the whole supply chain.”

“I’ll call you in a week”

I have high hopes for my next stop, Thauer Technology, a store with a bright blue awning.

Daniel Thauer is an information technology specialist born to a certified television master craftsman, and father-and-son expertise is housed under one roof. A bear of a man with brown-rimmed glasses, Mr. Thauer is surrounded by cardboard boxes and electronic devices, in various stages of function. I weave my way past a washer-dryer combo to the front desk. Mr. Thauer peers down at my broken stuff.

He motions at the Marantz, which I pass through a slot in the pandemic-era Plexiglas shield. He fiddles with the data door.

“People bring in the craziest things,” he tells me, “such as a power strip, which is nonsense because a new one costs only 5 to 10 euros. Strange. Not worth repairing. Neither is a hot water kettle with a broken casing.”

Well-known brands are going to be the best bet, because replacement parts are easy to procure. For everything else, it’s a 50-50 chance, says Mr. Thauer. “Maybe we can get a new casing for this. Maybe we can’t,” he says after dialing Marantz and getting no answer. “I’ll call you in a week.”

Still waiting

Back at home I put the flat iron in a cardboard box and stash it under the bathroom sink. I make a mental note to buy a new iPhone.

A week later, Mr. Urban calls: “Come pick up the fan.” I’d bought it in Asia, where I lived before moving to Europe, and he can’t get a replacement part for the motor.

It has now been two weeks, and my husband has stopped asking about his audio recorder; Mr. Thauer still hasn’t heard from Marantz.

“I think I’ll hear next week,” he says.

Berlin will decide at the end of this year whether to renew the program. It has been wildly successful in the economically challenged state of Thuringia in central Germany: Its first round in 2021 pulled in more than 6,000 applications and doled out $422,000. There, the program is in its fourth year.

I haven’t picked up my black fan from Mr. Urban; I like the idea of it hanging in the storage room with other abandoned appliances.

Reparaturbonus hasn’t worked for me – yet. But there’s satisfaction in having tried.

Film

Can ‘A Complete Unknown’ capture Bob Dylan?

The filmmakers of “A Complete Unknown” were faced with a daunting task, our critic writes: How do you get behind the mask of a willfully enigmatic artist like Bob Dylan?

Can ‘A Complete Unknown’ capture Bob Dylan?

Biopics about music icons occupy a long and occasionally honorable place in the movies. Most recently Maria Callas, Elton John, Freddie Mercury, Leonard Bernstein, Amy Winehouse, and Elvis Presley got the treatment. Jeremy Allen White is set to play Bruce Springsteen.

Now we have Timothée Chalamet as Bob Dylan in “A Complete Unknown.” Directed by James Mangold, who co-wrote the script with Jay Cocks, the film is not so much a demystification of Dylan as it is a confirmation of his mystique. The film’s title is all too descriptive.

Mangold confines the action to between 1961 and 1965, beginning with the 19-year-old Dylan arriving in New York, guitar slung over his shoulder, and culminating in his infamous appearance at the Newport Folk Festival. Playing an electric guitar, rather than his usual acoustic, he outraged many of the event’s folkies and organizers, who accused him of selling out.

It was fairly obvious, even at the time, that some sort of watershed cultural moment had occurred. As Elijah Wald wrote in his first-rate book “Dylan Goes Electric!” which the film draws heavily on, “What happened [at] Newport in 1965 was not just a musical disagreement or a single artist breaking with his past. It marked the end of the folk revival as a mass movement and the birth of rock as the mature artistic voice of a generation.”

This is an important story, which is not to say that “A Complete Unknown” is an important movie. The soundtrack, of course, is marvelous. (Chalamet acceptably subs for Dylan’s voice.) But I mostly connected to this film not because it contained anything revelatory, but because its history meshed with my own. It turned into a nostalgia trip, complete with great period recreations of 1960s Greenwich Village. I suspect many others who grew up with Dylan will react the same way. For those who didn’t experience this era in real time, Chalamet’s presence – his youthful movie star aura – may be enough to carry the film.

But the filmmakers have set themselves a near insoluble task: How do you get behind the mask of a willfully enigmatic artist like Dylan? For the most part, they duck the attempt.

To its credit, at least the movie doesn’t try to sugarcoat Dylan, whose reputation was never all that warm and fuzzy anyway. He is portrayed throughout as a careerist and a cad. His relationships with women are not pretty. Topping the list of cast-offs is folk goddess Joan Baez (well played by Monica Barbaro, who also does her own singing) and the artist-activist Sylvie Russo, Dylan’s first serious girlfriend. (She is played by Elle Fanning, and based on the real-life Suze Rotolo.) Dylan disparages Baez’s music as “like an oil painting in the dentist’s office.” Russo, often teary-eyed at his disloyalties, tells him at long last, “I don’t know you.”

She’s not alone. Nobody else in the film really does, either. And that’s the way Dylan wants it. Born Bobby Zimmerman, the middle-class Jewish kid from northern Minnesota purposefully exhibits few traces from his past. His real historical connection is to the music he loved while growing up. The most touching scene in the movie is right at the beginning, when Dylan visits his folk idol, Woody Guthrie (Scoot McNairy), in the New Jersey hospital where Guthrie is dying and unable to speak. Dylan plays Guthrie a song he wrote for him.

Present also in this scene is the film’s other major figure, Pete Seeger (a convincing Edward Norton), the icon who brought Dylan into the folk scene and championed his career until they unceremoniously split at the Newport event. Seeger, a founder of the festival, was a traditionalist. For him, folk music was a way of bringing people together in order to rally progressive causes.

Dylan deflected that role. He may have banded together a generation, but he was never a joiner. For him, the personal always eclipsed the political. I wish Mangold had not simplified the Seeger-Dylan rift. Seeger comes across at times like the genial Mister Rogers of the folk scene, while Dylan is its Marlon Brando. Mangold had an easier time of it when he made the Johnny Cash biopic “Walk the Line,” but Dylan is a far more complicated character than Cash. What may have begun as a descent into the personal depths of an enigmatic genius ends up as one more cog in the Bob Dylan myth machine.

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “A Complete Unknown” opens in theaters Dec. 25. It is rated R for language.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Christmas in China, the people’s way

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Anyone visiting China during Christmas should be prepared to find that the commemoration of Christ’s coming has been imported as a secular, commercialized “festival.” In public displays, Santa usually holds a saxophone. He is single. Instead of elves, he has sisters. Christmas trees, mostly fake and mostly set up by retailers, are known as “trees of light.” Don’t bother looking for a manger scene.

Yet for the past decade or more, young people have used Christmas Eve to give an unusual gift – “peace apples” – to close friends. Yes, apples. But not any apples. Only the finest kind, wrapped in boxes, adorned with ribbons, and imprinted with Christmas messages, often in gold, on the red skin. The thought behind these fruity presents is one of charity, humility, and goodwill.

So, visitors to China at Christmas, please note: A foreign holiday meant to worship the Prince of Peace has become a paean to peace for and by the Chinese people.

The Chinese are giving the lowly apple its due with their generous adornment, as if it’s a gentle babe lying in a manger wrapped in swaddling clothes. It’s not exactly apples for apples. But the truth behind Christmas can show up anywhere, even in a new tradition.

Christmas in China, the people’s way

Anyone visiting China during Christmas – the world’s most widely celebrated religious holiday – should be prepared to find that the commemoration of Christ’s coming has been imported as a secular, commercialized “festival.”

In public displays, Santa – called Old Christmas Person – usually holds a saxophone. He is single. Instead of elves, he has sisters. Christmas trees, mostly fake and mostly set up by retailers, are known as “trees of light.” Don’t bother looking for a manger scene. If you visit a mall decked out in red-and-green decorations, you may tire of “Jingle Bells” being played again and again.

For the less than 5% of Chinese who are Christians, there is an inkling of the day’s meaning in the Mandarin translation of Christmas: Holy Birth Festival (Shèngdàn jié).

Yet even that bow to God’s gift of divine truth was countered by a command last December from the ruling Communist Party that Christianity in China must be “in line with ... excellent Chinese traditions and culture.” (Some Christmas displays do include dragons.)

Well, party leaders might be glad that the masses over recent decades have devised a very popular Chinese tradition. Young people now use Christmas Eve to give an unusual gift – “peace apples” – to close friends.

Yes, apples. But not any apples. Only the finest kind, wrapped in boxes, adorned with ribbons, and imprinted with Christmas messages, often in gold, on the red skin. The crafted fruit can cost six times more than normal. One box even cost more than an Apple iPhone. And this in a country that produces about half of the world’s apples and consumes the most apples.

While the thought behind these fruity presents is one of charity, humility, and goodwill, the origin of “peace apples” is less lofty. In Mandarin, the first syllable of the word for apple (píngguǒ) is the same as the first syllable in the word for Christmas Eve (píngān yè), which is translated as “peace night.” In other words, a fun play on words has become a solemn and symbolic act of the Christmas spirit.

So, visitors to China at Christmas, please note: A foreign holiday meant to worship the Prince of Peace has become a paean to peace for and by the Chinese people. While their rulers claim China is a global promoter of peace – something people in Taiwan, Tibet, Vietnam, Japan, and the Philippines would dispute – real peace on Earth is being expressed heart to heart. The Chinese are giving the lowly apple its due with their generous adornment, as if it’s a gentle babe lying in a manger wrapped in swaddling clothes.

It’s not exactly apples for apples. But the truth behind Christmas can show up anywhere, even in an excellent new tradition.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Listening for the angels

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

We can hear and heed God’s uplifting and healing messages on Christmas and every day.

Listening for the angels

Now there were ... shepherds living out in the fields, keeping watch over their flock by night. And behold, an angel of the Lord stood before them, and the glory of the Lord shone around them, and they were greatly afraid. Then the angel said to them, “Do not be afraid, for behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy which will be to all people. For there is born to you this day in the city of David a Savior, who is Christ the Lord. And this will be the sign to you: You will find a Babe wrapped in swaddling cloths, lying in a manger.”

And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host praising God and saying:

“Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, goodwill toward men!”

– Luke 2:8-14, New King James Version

ANGELS. God’s thoughts passing to man; spiritual intuitions, pure and perfect; ...

– Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 581

Let every creature hail the morn

On which the holy child was born,

And know, through God’s exceeding grace,

Release from things of time and place.

I listen, from no mortal tongue,

To hear the song the angels sung,

And wait within myself to know

The Christmas lilies bud and blow.

– John Greenleaf Whittier, “Christian Science Hymnal,” No. 170, adapt. © CSBD

Viewfinder

Noche de paz

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. As mentioned in the intro, today will be the last Christian Science Monitor Daily before Christmas. Next week, you will receive a series of special sends highlighting our favorite stories of the past year. Your next Daily will arrive Monday, Dec. 30. Happy holidays!