On a March evening in 1976, when Jimmy Carter was mingling in the living room of a political supporter in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, someone at the small campaign event asked the former Georgia governor a point-blank question: “Are you a born again Christian?”

It startled him that moment, but it was really as natural a question as any for the one-time peanut farmer from the heart of the rural South. He’d been open about his devout Baptist faith during his long-shot campaign to become president of the United States, so he simply answered, “Yes.” He just assumed, as he later explained, “that all devout Christians were born again, of the Holy Spirit.”

It was just a few days before North Carolina’s make-or-break primary, but after acknowledging he was a “born again” Christian, all political hell broke loose, as many observers noted at the time.

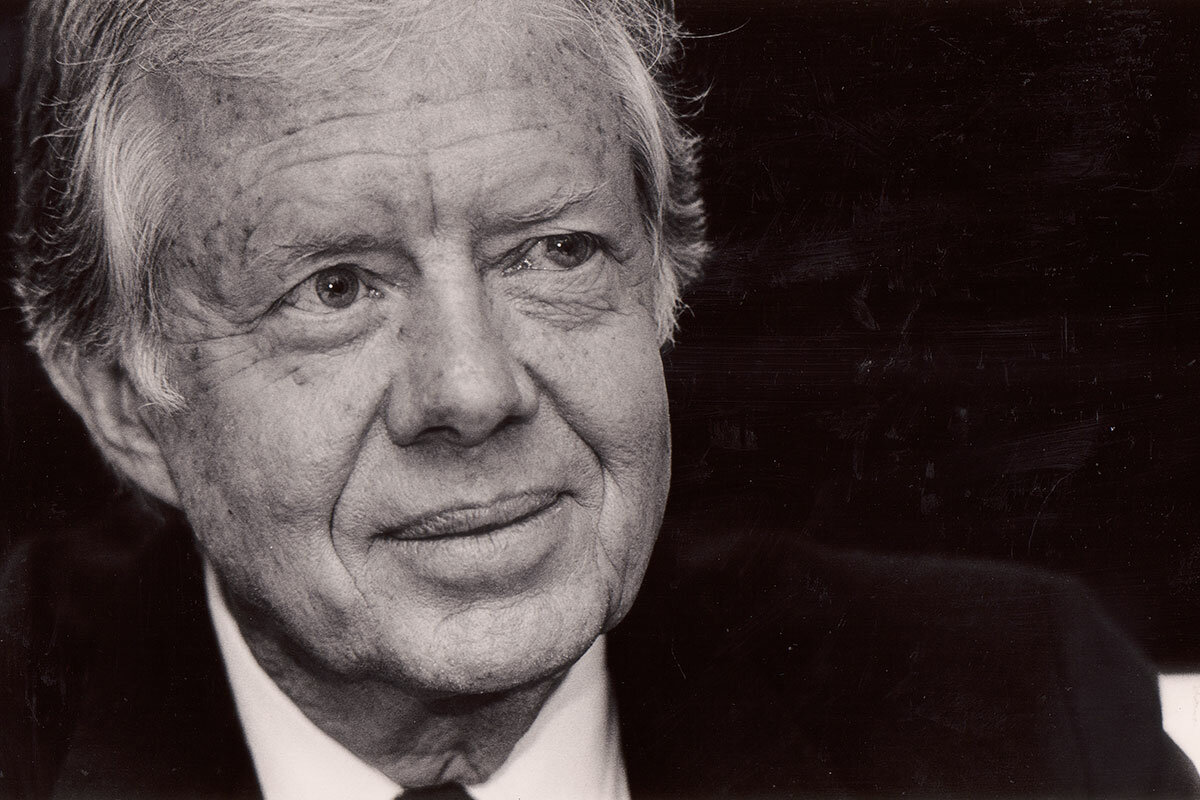

As the nation mourns Sunday the passing of James Earl Carter Jr., its 39th president and the longest-serving ex-president in U.S. history, there is something poignant about that moment in history almost half a century ago. At that time, the term “evangelical” was barely a blip on the radar screens of those in the media and “born again Christian” hardly registered for those steeped in the arts of making policy and garnering votes.

“When I recount the story, I often say that when Jimmy Carter declared that he was a born again Christian at this campaign event in North Carolina, he sent every journalist in New York to his or her Rolodex to find someone to tell them what in the world he was talking about,” says Randall Balmer, historian of American religion at Dartmouth College and the author of “Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter.”

The election in 1976 in many ways marked the reemergence of this subgroup of American Protestants who had consciously retreated from public life after the “modernist” controversies of the early 20th century, including the Scopes Trial and battle against the teaching of evolution in public schools.

Throughout his life, which spanned a century, President Carter himself would define his evangelical faith as “inextricably entwined with the political principles I have adopted.” It would infuse the decisions he made at every stage of his career as a public servant and define his life in ways both good and bad, historians say.

“As president he spoke openly of his Christian faith and all it entailed: daily prayers, abhorrence of violence, the belief that the meek shall inherit the earth, the courage to champion the underdog,” wrote the presidential historian Douglas Brinkley in 1998. “Most of all, his faith taught him that a clear conscience was always preferable to Machiavellian expediency – a pretty healthy attitude that proved both Carter’s greatest strength and his bane.”

Governor Carter embraced what was then becoming a controversial identity. His stump speech was distinct from the other Democratic candidates, and he peppered it with appeals to “godly values,” using explicit Christian entreaties for “tenderness” and “healing” and “love.”

“At least part of the stir over Carter’s shirtsleeve religiosity is that he seems to practice what he preaches,” Newsweek magazine mused a few days after the “born again” question made headlines across the country. “Kennedy went to Mass and Richard Nixon spoke affectionately of his Quaker mother, but neither appeared to be truly religious.”

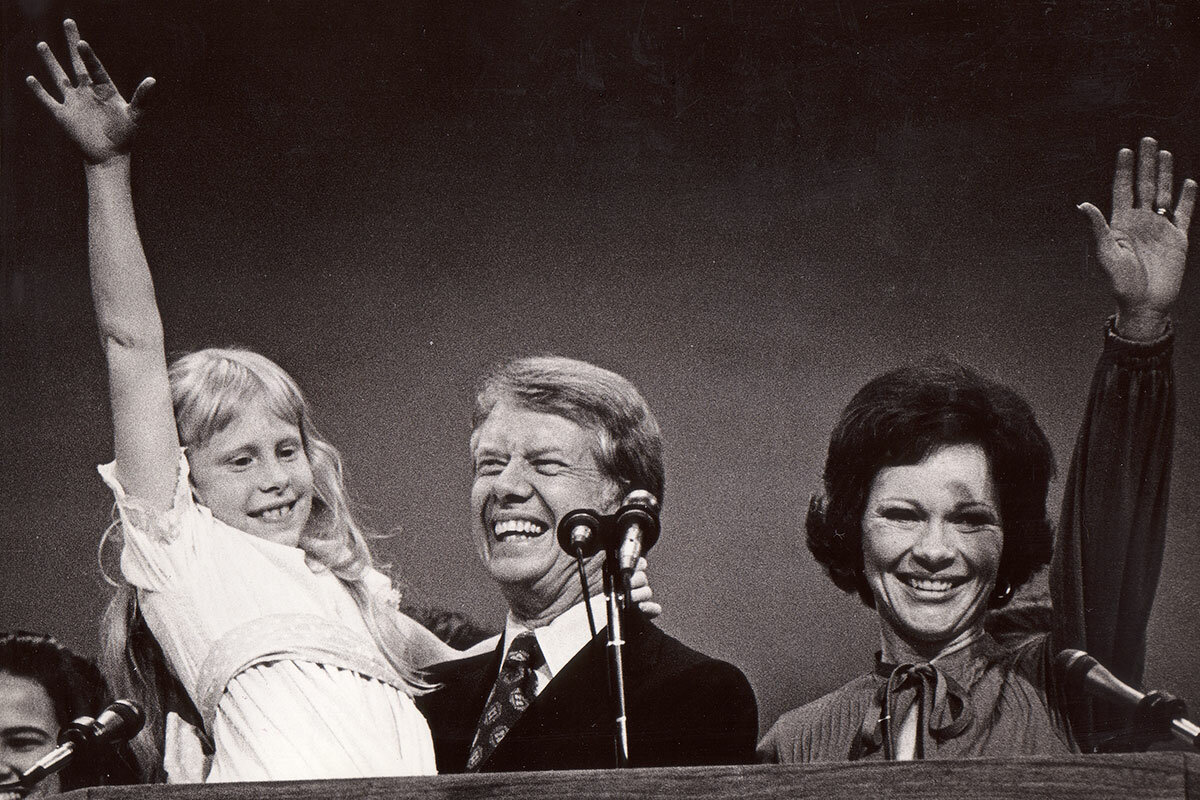

With his toothy smile and soft-spoken drawl, Governor Carter had been campaigning as a Washington outsider, too, emphasizing his simple roots as a peanut farmer from a place called Plains, the farming hamlet where he and his wife, Rosalynn, had both been born and raised. That’s just how they talked about their Christian faith in those parts.

Mr. Carter told journalists he prayed “about 25 times a day, maybe more” and ended each day reading the Bible. “It’s like breathing,” he said in describing his faith to reporters who began to ask more pointed questions. “I’ve wondered whether to talk about it at all. But I feel I have a duty to the country – and maybe to God – not to say ‘no comment.’”

Now, for the first time, Gallup began to ask voters if they were “born again.” They found that nearly 50 million Americans said they were. In October, Newsweek declared 1976 to be “The Year of the Evangelical.” Journalists and political scientists were now trying to parse the particulars of evangelical theology and how it might affect how people would vote.

“Evangelicals suddenly find themselves number one on the North American religious scene,” proclaimed the evangelical magazine Christianity Today a month before the election, noting the impact of Carter’s candidacy. “After being ignored by much of the rest of society for decades, they are now coming into prominence. ... Evangelical recovery has taken fifty years.”

But there was also a certain irony as Americans put the experiences of Vietnam and Watergate behind them and found themselves drawn to the pious optimism of Jimmy Carter and elected him president of the United States.

“America desperately needed a Jimmy Carter in 1976,” says Barbara Perry, director of presidential studies at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center. “And so for him to come out of almost from nowhere to earn the nomination by sheer shoe leather in Iowa and New Hampshire, and to be the person outside of the establishment and to say, I’m not from Washington, I will never lie to you, I’m a born again Christian – what I say is that, he really did bring a close to the Watergate period.”

In just four years, however, American Evangelicals would decisively turn away from Carter – who won the votes of about half of white Evangelicals in 1976, scholars estimate – as well as his Democratic Party. Not only would born-again Christians galvanize around the candidacy of Ronald Reagan, they would also soon become the most potent and reliable political force in the Republican Party, if not the country, for decades to come.

As Dr. Balmer alludes in the epigraph of his presidential biography, a quote from the Gospel of St. John: “He came unto his own, and his own received him not.”

In July of 1979, exactly three years from the day that he accepted the Democratic nomination for president, President Carter was getting ready to give one of the most important speeches of his now increasingly unpopular presidency.

Just a year earlier, the president had demonstrated what historians would later call one the most deft and subtle acts of shuttle diplomacy in the nation’s history, achieving a peace accord between Israel and Egypt at Camp David, the presidential retreat in Maryland. As it turned out, this peace agreement would hold, unbroken, for the rest of his life and to this day.

But now with a 25% approval rating, the lowest since Harry Truman, President Carter had planned to deliver a major address on the nation’s energy crisis on the Fourth of July. He canceled it at the last minute, however, and retreated to Camp David for 10 days – fueling speculation that the president was ill.

The energy crisis was punctuated by an oil embargo from mostly Middle Eastern countries angered at U.S. support for Israel. There were gas shortages, filling newscasts with images of Americans waiting in lines stretching down the block to fill their tank. Inflation stood at 13%, and sky-high interest rates and unemployment were bogging down the economy. At the same time, NASA’s Skylab space station was about to crash out of its orbit, and no one quite knew where it would land.

So, in front of a national television audience, President Carter delivered an address titled, “A Crisis in Confidence,” in which he characterized the nation as mostly “confronted with a moral and a spiritual crisis.”

“In a nation that was proud of hard work, strong families, close-knit communities, and our faith in God, too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption,” he said. “Human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns. But we’ve discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning. We’ve learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose.”

Two days after delivering this speech, President Carter fired four of his Cabinet secretaries and demanded the resignations of dozens of government officials. This purge, immediately following a national address that would become known, infamously, as the “malaise” speech, gave the impression of an administration that was unsure, unsteady, and in fact falling apart.

In some ways, his sense of conscience and spiritual rectitude could have indeed become a bane within his presidential decision making, historians say. “He was a bit of a contrarian, and he is just a very stubborn man,” says Dr. Balmer. “There’s no question about his sense of moral rectitude, which a lot of people find insufferable. His attitude was: I’m going to do the right thing, damn the torpedoes, sort of thing. That didn’t help him either.”

And then, just a few months later, a group of Iranian militants stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehran and took 52 Americans hostage for what would span 444 days and dominate the last year of Mr. Carter’s presidency. It was yet another crisis, and his effort to rescue the hostages with a daring commando mission in the desert ended in disaster after a helicopter crashed into a transport aircraft, killing eight U.S. service members.

President Carter’s inability to rescue the hostages in the U.S. Embassy in Tehran remains one of the most lasting blights on his presidential legacy, but historians also note there were significant accomplishments.

He was one of the most consequential U.S. presidents in terms of environmental policy, passing numerous new laws to clean up and protect the environment. He also instituted lasting policies to diversify the nation’s energy sources.

“He also implemented an official affirmative action policy for judicial appointments at the federal level when a lot of people didn’t think in those terms,” says Dr. Perry at the Miller Center.

When Mr. Carter took office, only eight women and 31 people of color had ever been appointed a federal judge. In his four years as president, Mr. Carter successfully nominated 40 women, including eight women of color, and a total of 57 non-white justices.

“As part of that, he named Ruth Bader Ginsburg to the D.C. Circuit, which was her jumping off point, her proving ground to end up on the Supreme Court,” Dr. Perry says. “That in itself is quite a legacy.”

President Carter also brought a certain moral vision to U.S. foreign policy, a sustained focus that led to mixed results, many historians say.

“I think one accomplishment was to introduce and to insist on the centrality of human rights in American foreign policy, doing away with the kind of reflexive dualism of the Cold War era,” says Dr. Balmer. “One example is that, one of the first things he did was to press for the revision and ratification of the new Panama Canal treaty.”

“A lot of people told him, including his wife, Rosalynn, wait till your second term,” he says. “But he was just determined, ‘No, this is the right thing to do, and I’m going to do it’. He recognized that if the United States is going to have any meaningful relationship with Latin America ... we needed to get out of the colonial business there.”

“He expended a great deal of political capital early in his administration, and he just didn’t get it back in many ways,” Dr. Balmer says.

After losing his bid for a second term to Republican Ronald Reagan, Mr. and Mrs. Carter returned to their long-time home in Plains, Georgia, the small ranch house on Woodland Drive they purchased in 1961. The Carters would live there for the rest of their lives. The two were married for 77 years – the longest presidential marriage in history – before Rosalynn Carter’s death in November 2023.

“Rosalynn was my equal partner in everything I ever accomplished,” Mr. Carter said in a statement after her passing. “She gave me wise guidance and encouragement when I needed it. As long as Rosalynn was in the world, I always knew somebody loved and supported me.”

Beyond her powerful role as an adviser, during his presidency she emerged on the national stage as an advocate for mental health and for equal rights for women.

The 1980 election was a crushing defeat, and it was not lost on Mr. Carter that Evangelicals and born-again Christians had voted overwhelmingly for the former governor of California. “When I asked him about it, he acknowledged that he took the evangelical vote for granted going into the 1980 campaign,” says Dr. Balmer. “He was blindsided by their support for Reagan.”

Having left office at 56, Mr. Carter began to see his post-presidency as his second term. “He said that had he won a second term, it’s likely that he would not have been so energetic and ambitious as he was in activities after he left the White House,” Dr. Balmer says.

After decades of appraisals of Mr. Carter’s presidency, there has been something of a general consensus about his place: President Carter was a middling, one-term U.S. president buffeted by a “malaise” of problems at home and abroad.

But he would go on to become the most accomplished former officeholder in U.S. history by far, historians say.

“I always think that’s the supreme irony of the Carter presidency,” says Dr. Perry. “He got the nomination and won the election because he was not a Washington insider, and that’s exactly what we needed as a country at the time. The pendulum swung as far as it could from Richard Nixon and Watergate. And yet, he wasn’t the best person, perhaps, to govern and be president of the United States at that time.

“But then that ties together his post presidency,” she continues. “Because then he goes back to his essence of morality and good deeds and his born-again Christian faith, which he then carried throughout the world.”

Reemerging in public life in 1982, Mr. and Mrs. Carter founded The Carter Center in partnership with Emory University in Atlanta. They aimed to champion causes important to them during their time in the White House, including human rights and democracy, public health, and helping to resolve conflicts around the globe.

The center has been successful, helping to develop village-based health care centers in Africa. It has also assisted in monitoring elections across the world. One of its most remarkable achievements, however, is leading a coalition that would virtually eradicate the Guinea worm.

There were 3.5 million cases of the parasite in the mid-1980s, when The Carter Center began its efforts. ”I’d like for the last Guinea worm to die before I do,” Mr. Carter said at a press conference in 2015. In 2023, there were 13 known cases. In 2024, and as of this publishing, there have been seven Guinea worm cases reported around the globe.

With one of his lasting legacies being the Camp David peace accords, Mr. Carter continued to serve as a kind of freelance ambassador and roving peacemaker. He helped the Indigenous Miskito people in Nicaragua return to their homes after long conflicts with the Sandinista government. He traveled to Ethiopia to help mediate a conflict with Eritrea. And he continued to assist the State Department in sensitive negotiations with dictators such as Kim Il Sung of North Korea and Muammar Qaddafi of Libya.

As a public figure, the former president also championed Habitat for Humanity International, often holding a hammer and wearing a hardhat as he helped build homes for people in need. In 2002, Mr. Carter was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

For nearly 40 years, too, Mr. Carter would take his turn to teach Sunday School at his longtime congregation, Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains, and he would continue to invoke “a religious faith based on kindness toward each other” and rooted in a commitment to peace.

“I have a commitment to worship the Prince of Peace, not the prince of preemptive war,” Mr. Carter said at a Monitor Breakfast in 2005, criticizing the decision to invade Iraq. “I believe Christ taught us to give special attention to the plight of the poor.”

Asked about his place in history, he later told the gathering, “I can’t deny that I am a better ex-president than I was a president. I would like to be remembered as someone who promoted peace and human rights.”

Editor’s note: This story, which was originally published on Dec. 29, was updated to correct the number of Guinea worm cases reported in 2024. There have been seven. The first name of presidential historian Douglas Brinkley has also been corrected.