When Chávez re-nationalized his country’s huge oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA), it sent a message to the international oil industry: no more business as usual in Venezuela. Instead of foreign companies owning a majority share of development products, the PDVSA would get a minimum 60 percent share. Royalty rates had already been raised. Companies who didn't agree to the new rules, such as Italy's Eni and France's Total, saw their facilities taken over. Others, like the US-owned Exxon Mobil and ConocoPhillips, simply left.

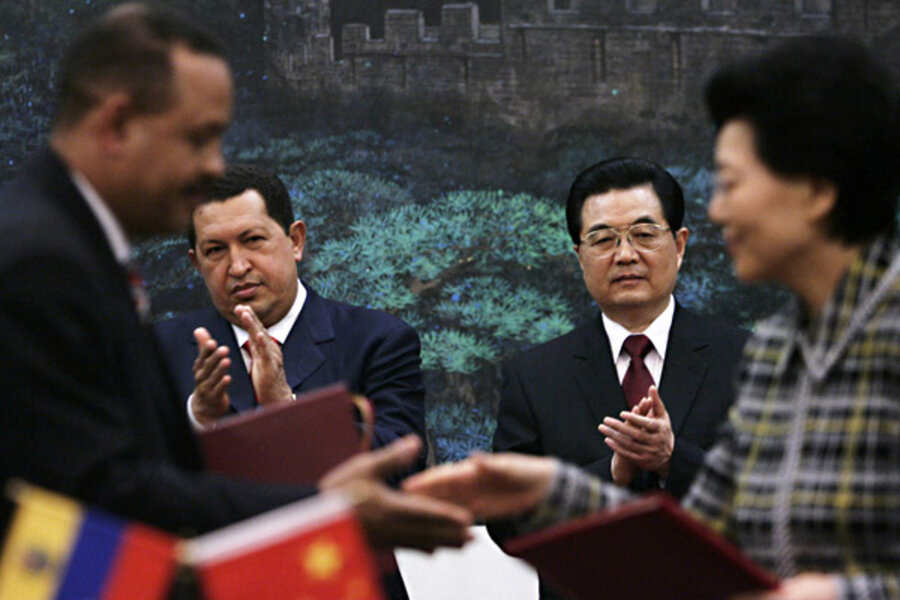

By 2009, it was clear that Chávez's strategy had failed to stop the slide in Venezuela's oil production, and he began allowing more foreign investment in the Orinoco Belt. China, India, Russia, Spain, Japan, Vietnam, and even Chevron in the US gained access to six blocks in the belt as minority partners with PDVSA. If all these projects come on stream, Venezuela projects that they would produce 2.1 million barrels of syncrude a day. Western analysts are pessimistic that Venezuela will achieve that boost without liberalizing its rules and opening up to more foreign investment. With a chaotic and arbitrary business environment within the country, foreign producers may be reticent to commit large investment sums to bring Venezuela's oil production back to pre- Chávez levels.