Deeper down, are coral reefs surviving climate change?

Loading...

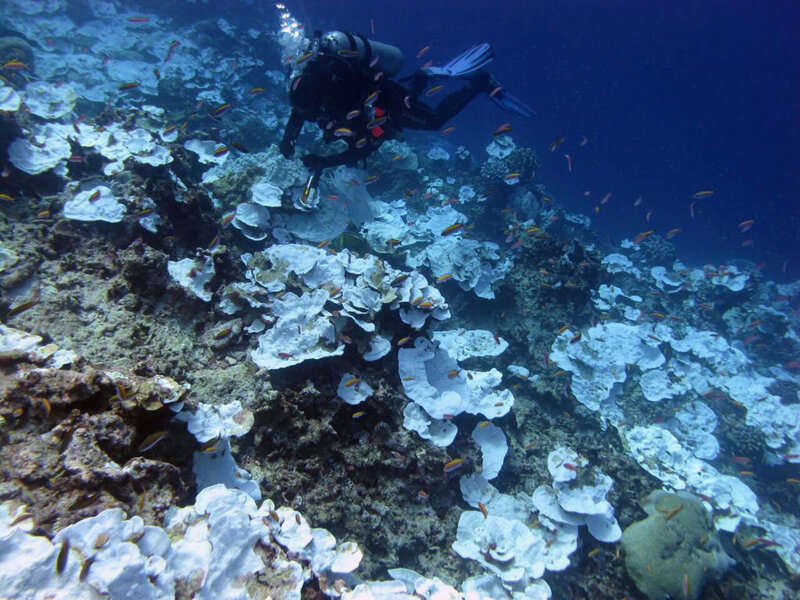

The next time you see a picture of a coral reef bleached ghost-white by warming seas, remember that there's a good chance it was taken in the photic zone: the brightly lit layer of water that extends about 50 meters below the surface.

Australian marine biologist Tom Bridge wants to shift our focus deeper. Speaking at the World Science Festival in Brisbane, Australia, on Friday, he pointed out that two-thirds of all coral lives in the 50- to 700-meter (165 to 2,300 feet) range. That’s a habitat that reaches deeper than the height of New York’s One World Trade Center.

In particular, he wants to call our attention to the “mesophotic zone,” between 50 to 150 meters (165 to 492 feet), where enough sunlight reaches to sustain many of the same corals found higher up. “We have this sort of intermediate zone between the 50 to 150 meter depth range that's really been ignored for a long period of time,” Dr. Bridge, the senior curator at Queensland Museum in Brisbane told the World Science Festival audience.

Studying this zone could do more than just fill a gap in scientific knowledge. The mesophotic’s greater depth and colder temperatures provide a buffer against climate change and other well-known threats facing reefs and studying it could change scientific methods for protecting the reefs overall.

“Sometimes these deeper areas are less vulnerable to these disturbances than shallow water habitats,” Bridge explained. In oceans, a transition layer called the “thermocline” separates warmer and colder waters. During one mesophotic research dive in Hawaii, recently described in Science magazine, the team reached waters as cold as 10 degrees Celsius, or 50 degrees F.

Along with the cold temperatures, scientists have other good reasons to stay in the shallows. Standard diving protocol involves pausing at regular intervals during an ascent.

To make enough time for these pauses, divers who go deep typically use a rebreather, which re-circulates exhaled air, rather than breathe compressed air from a scuba tank. Even then, a research dive at 100 meters (328 feet) might involve 20 minutes of work on the reef, followed by two hours of stops on the way up.

Despite the challenges, Bridge thinks studying the mesophotic could offer a more holistic – and encouraging – picture of Earth’s reefs. The same temperatures that chill divers to the bone could protect the mesophotic’s corals from the bleaching that occurs closer to the surface. They’re also farther removed from other threats, such as overfishing and coastal development.

Understanding if these traits make the mesophotic stronger would take more research. "Compared to what we know about shallow coral reefs, everything in the deep coral reefs is a big question mark," Richard Pyle, an associate zoologist at Bishop Museum in Honolulu who specializes in deep-water coral climate, told Science magazine.

Bridge wants that to change. "A lot of the time it's out of sight, out of mind.... If you can't see it, it doesn't become included in conservation plans and things like that."