Uganda's pride: Lions test locals' patience

| Kampala, Uganda

Ugandans have mixed feelings about lions.

The predatory cats are a boon for tourism, which accounts for 9 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product. But for many, the lions and other large predators are a source of near-constant anxiety.

That tension came to a head in April when 11 lions were found dead in Uganda’s Queen Elizabeth National Park. Wildlife officials suspect that the lions were poisoned by pastoralists who have lost livestock to the cats. Since then, wildlife officials have redoubled efforts to help residents find ways to live in harmony with these carnivores.

Why We Wrote This

Living near predators presents challenges for communities around the world. In Uganda, wildlife officials have redoubled efforts to help locals live in harmony with lions after 11 of the big cats were poisoned in April.

Central to the conflict is a sense that local residents shoulder all the burdens of hosting these carnivores without reaping any of the economic benefits that their presence brings the country. The Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) is trying to rebalance that equation with a series of initiatives including revenue-sharing programs, compensation packages for lost livestock, and employment opportunities.

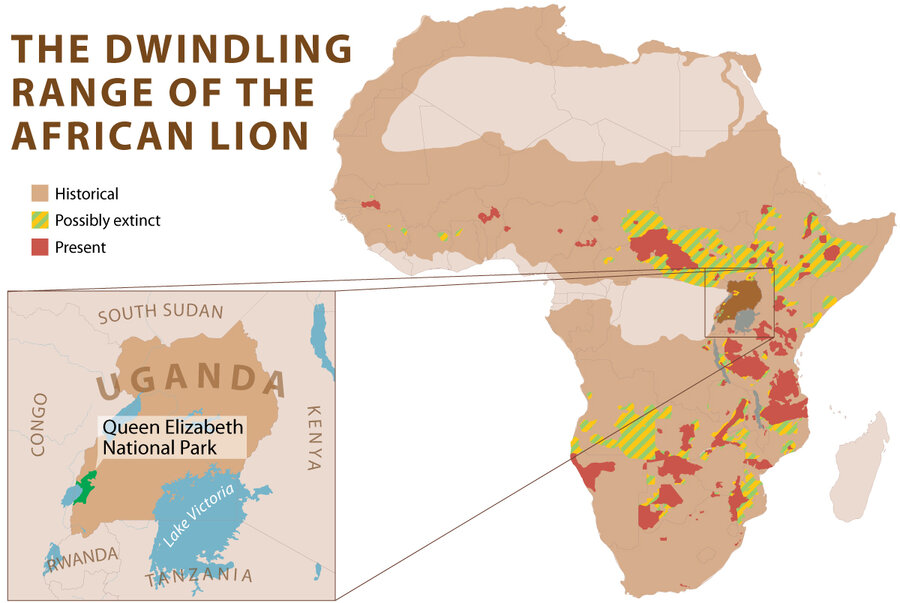

The African lion, Panthera leo, plays a crucial role in the savanna ecosystem. As apex predators, the giant cats keep herbivore populations from ballooning to numbers that cannot be supported by the land. Their tendency to prey upon the weakest of the herd is thought to keep parasites and disease in check. At the turn of the 20th century, an estimated 200,000 lions roamed throughout much of Africa. Today, those numbers have dwindled to just 20,000, and the cats have been declared extinct in 26 countries.

Uganda is home to some 400 lions, about 130 of which live in Queen Elizabeth National Park. The park’s Ishasha sector hosts one of just two known populations of tree-climbing lions in the world. The park is a haven for some of Africa’s most iconic safari species, including elephants, buffalo, and leopards. In 2017, nearly half a million foreign visitors traveled to the park in hopes of glimpsing this rich biodiversity.

But animals frequently wander outside the park and can cause problems for surrounding communities. Leopards and lions kill livestock. Elephants trample gardens. And primates have even been known to attack children. (In early June a chimpanzee reportedly kidnapped a 5-month-old infant, though villagers were able to recover the child. ) Frustrated, locals have set out snares for elephants and poison for carnivores.

Cris Mongly Kaseke, a conservationist and resident of the Kasenyi Fishing Village within the park, says that people lash out at the animals because they don’t see any benefit to living alongside such dangerous creatures. He recently sold all five of his goats after another was eaten by a leopard. He received compensation for the lost goat through an experimental program funded by tourist dollars, but he was worried that keeping the remaining goats would attract more predators.

The goats had been loan collateral and a potential source of income in the event of illness. “They were my insurance,” he says.

Mounting tensions

Additional conflicts arise when pastoralists lead their livestock into the park in search of pasture during dry spells. The park is off limits to domesticated animals, and the presence of trespassing pastoralists and their livestock can lead to tense run-ins with heavily armed UWA officers.

Chief park warden Edward Asalu is hopeful that UWA’s efforts will help alleviate these tensions with the local communities. In addition to offering compensation to individuals like Mr. Kaseke who have lost livestock, the UWA is developing a revenue-sharing fund that distributes 20 percent of visitors’ fees back to the community.

Park officials have been experimenting with a beekeeping program to both discourage animals from wandering outside the park and to provide an economic lift to local communities. The park provides beekeeping training to locals, who then establish hives near the perimeter of the park. Hives full of stinging bees deter animals from leaving the park and provide beekeepers with honey to sell.

Additionally, Mr. Asalu is hoping that local residents will start to view the UWA as a source of employment rather than as an adversary.

“We are giving first priority to locals with the right qualifications in the recruitment for game rangers,” he says.

Kaseke, who has a certificate in wildlife and allied natural resource management from the Uganda Wildlife Training Institute based in Kasese District, is skeptical of that promise, as he has seen little effort to recruit locally. He has, however, worked with the UWA to secure a beekeeping permit for his local beekeepers association.

He has additional concerns about the way the revenue-sharing program has been administered. He would rather see those funds distributed directly to the local community than at the district level.

“[The fund] has been misused,” he says. “It is given to the wrong people.”

Asalu acknowledges that there have been delays and diversions by district officials, but he says that the current laws prohibit the UWA from distributing the funds directly to the communities.

Light at the end of the tunnel

A bill recently introduced in Parliament, the Uganda Wildlife Bill 2017, would both codify efforts to compensate pastoralists who lose livestock outside the park and strengthen the penalties for people who commit crimes against wildlife.

Kaseke worries that the bureaucratic process for compensation outlined in the bill is too cumbersome.

“It will not help because there are a lot of procedures, including getting letters from local officials who demand small bribes,” he explains. “The claimants will lose interest.”

Doreen Katusiime, the permanent secretary in the Ministry of Tourism, Wildlife and Antiquities, is optimistic that Parliament will be able to shape the bill in a way that will help protect communities and their wild neighbors.