Bluer skies, less greenhouse gas. What happens after the pandemic?

Earlier this month, health care experts from across the United States gathered to address hundreds of journalists and policymakers by webinar. But their focus was not testing, nor vaccines, nor “herd immunity.” It was not even COVID-19, really. Instead, their focus was climate change.

“While many see issues like climate change and biodiversity loss as far from what’s going on right now … I see this as the time to talk about it,” said Aaron Bernstein, a pediatrician at Boston Children’s Hospital and a professor at Harvard Medical School. “Climate solutions are, in fact, pandemic solutions.”

A few days later, economists and policy experts with the World Resources Institute held their own panel discussion. The message was similar, and the audience one of the largest in the organization’s history. The experience of and response to COVID-19, proclaimed expert after expert, was intricately tied to climate.

Why We Wrote This

In the pandemic, people worldwide are proving they can make personal sacrifices that benefit others. Researchers say now’s the time to push for more policies requiring similar efforts for climate change.

Indeed, increasing numbers of researchers and policymakers, scientists and health care practitioners, are looking at the coronavirus through an ecological lens. Whether they are focused on consumer behavioral shifts, changes in emission outputs, or policy decisions that might help or hurt long-term goals for green infrastructure, they are seeing in this moment a pivotal chance to address climate change.

“As we respond to the very imminent economic and health crisis, can we also tackle the climate and sustainability crisis?” asked Manish Bapna, WRI’s managing director and executive vice president.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

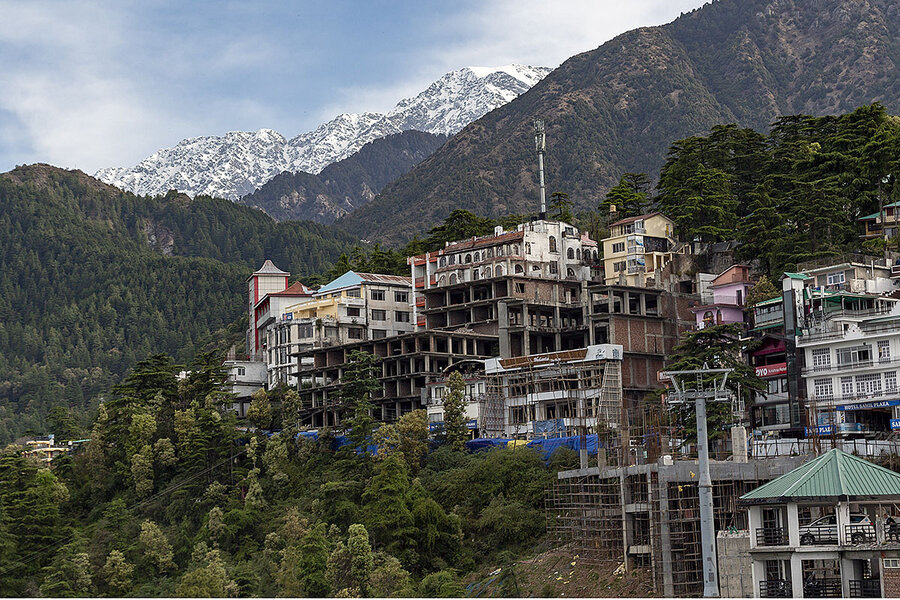

There have been a number of short-term environmental shifts connected with how the world is coping with the pandemic. China’s carbon emissions dropped 18% between the beginning of February and mid-March, according to data compiled by the website CarbonBrief. Pollution over India has decreased dramatically, according to satellite images from NASA’s Earth Observatory. And in the U.S., a dramatic decrease in air travel, as well as a drop in vehicular travel, has also lowered emissions.

But many of these changes are temporary, researchers say, and may barely register on any long-term analysis of global carbon emissions. The drop in China’s carbon output, for instance, came alongside a lockdown over much of the country and a related plunge in factory operations. As the country reopens, says Fang Li, chief representative of the World Resources Institute in Beijing, emissions are expected to rebound along with the economy. After the global financial crisis of 2008 and 2009, Dr. Fang and others point out, global emissions grew rapidly.

Renewing a focus

For many climate advocates, this is a reason to push green initiatives now. Environmentalists worry that unless policymakers focus on climate as part of their economic packages, the pandemic could lead to policy shifts that would undermine years of hard-won climate victories. Indeed, the Trump administration in late March announced that it would weaken Obama-era fuel standards that mandate increased fuel efficiencies for automobiles. It also announced last month that the Environmental Protection Agency will not enforce environmental regulations during the pandemic.

“What we have to worry about is whether ... policy changes are going to be long term or short term,” says Christopher Jones, director of the CoolClimate Network at the University of California, Berkeley. “If we roll back standards and they remain in place when the economy comes back, we are going to have a real problem.”

Researchers say that a green economic stimulus package could both help the U.S. ensure long-term sustainability and rebound from the crushing economic impact of the pandemic. (More than 26 million Americans have filed for unemployment benefits since March 15, according to the U.S. Labor Department.) Many environmentalists look at the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the stimulus package signed by President Barack Obama in 2009, as an example of how government initiatives can spur climate-friendly industry. That bill, which earmarked some $90 billion to promote green energy, is widely credited with launching the widespread renewable energy sector in the U.S.

“Economic measures should focus on climate as well as jobs and livelihood,” Mr. Bapna said during the WRI panel.

But as Kenneth Gillingham, a professor at Yale University and a research fellow at the National Bureau of Economics Research, points out, the pandemic itself has slowed renewable energy efforts.

“There’s a slowing down of building new solar farms, of new wind facilities,” he says. “Some projects are hitting the pause button. Other projects may not happen for a long time.”

And while there is hope for a green renewal, he suspects the future will be a good deal more nuanced.

“Entirely rebuilding our economy as a green economy? It’s a wonderful vision, but I don’t believe that’s what we’ll likely see,” he says.

Inequality, exacerbated

But a move toward environmental sustainability, says Dr. Bernstein, is going to be crucial not only for combatting a climate crisis, but for helping some of the people most impacted by the coronavirus. As he points out, both the pandemic and the impacts from climate change disproportionately affect people of color and other marginalized groups.

There is, he and others say, a hopeful lesson to be taken from the massive lifestyle and economic shifts seen across the globe in response to COVID-19. For years, popular wisdom has said that people simply would not engage in the sort of behavior changes necessary to fight climate change; that they wouldn’t stop traveling, wouldn’t stop consuming, wouldn’t sacrifice material comforts and help save others who are most immediately at risk from climate change. Now, the response to the pandemic suggests otherwise.

“We are able to mobilize the entire global economy and population for an imminent threat,” says Dr. Jones. “Both climate change and this pandemic both affect the most vulnerable. But everybody is willing to make personal sacrifices to protect the most vulnerable. I think that’s quite new.”

The question, he and others say, is whether people will be able to see climate change as a similarly “imminent threat,” deserving of action. While climate researchers look at the world’s increasingly frequent and severe natural disasters and see a direct connection to human behavior, research shows that most everyday people still feel disconnected from both the impacts and causes of climate change.

“We don’t experience risk properly,” says Katharine Hayhoe, professor and director of the Texas Tech University Climate Science Center.

But with the coronavirus, researchers say, there is a chance to shift.

“It can make people feel that what was previously unthinkable is plausible,” Dr. Jones says. “They know what the experience feels like.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.