In Pictures: Sea turtle rescuers race against cold

Every winter in New England, as the ocean waters chill and frigid winds drive many residents indoors, a cadre of volunteers heads to the beach. Day and night they search the sands of Cape Cod Bay in Massachusetts for stranded sea turtles.

Most of these marine reptiles find their way toward warmer waters. But each year, especially after sudden drops in temperature, hundreds of sea turtles, particularly young ones, become cold stunned, tumbling in the waves and onto the shore, unable to eat, drink, or move. The Cape’s peninsular hook of land catches the fledgling reptiles as they belatedly try to head south. Animal lovers armed with plastic sleds, towels, headlamps, and training are on watch after high tides from November through January.

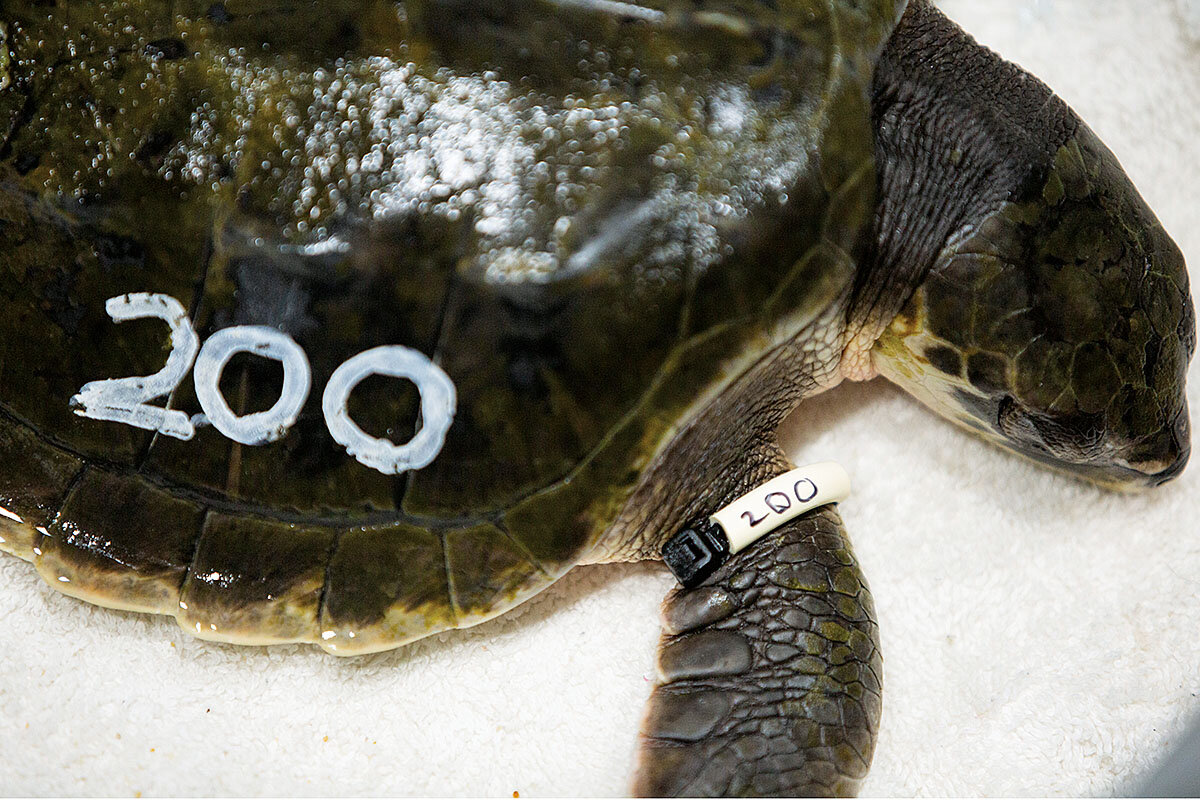

Each rescued animal is rushed to the intensive care unit at Mass Audubon Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary where they are weighed, measured, photographed, and assigned a number that will follow them on their journey to recovery. On one especially busy December day, 94 turtles arrived in need of urgent care; this season more than 500 have been treated.

Fortunately, most turtles are found alive, but those that are not are studied for research. Marine biologist* Karen Dourdeville, who coordinates the rescue efforts, says her staff has learned to warm the animals gradually (the room is kept at 55 degrees), to talk softly, and to handle the precious creatures as little as possible. The most frequently rescued species is the Kemp’s ridley, the rarest and most endangered sea turtle in the world. Green turtles, which are also endangered, and loggerheads are also frequent patients.

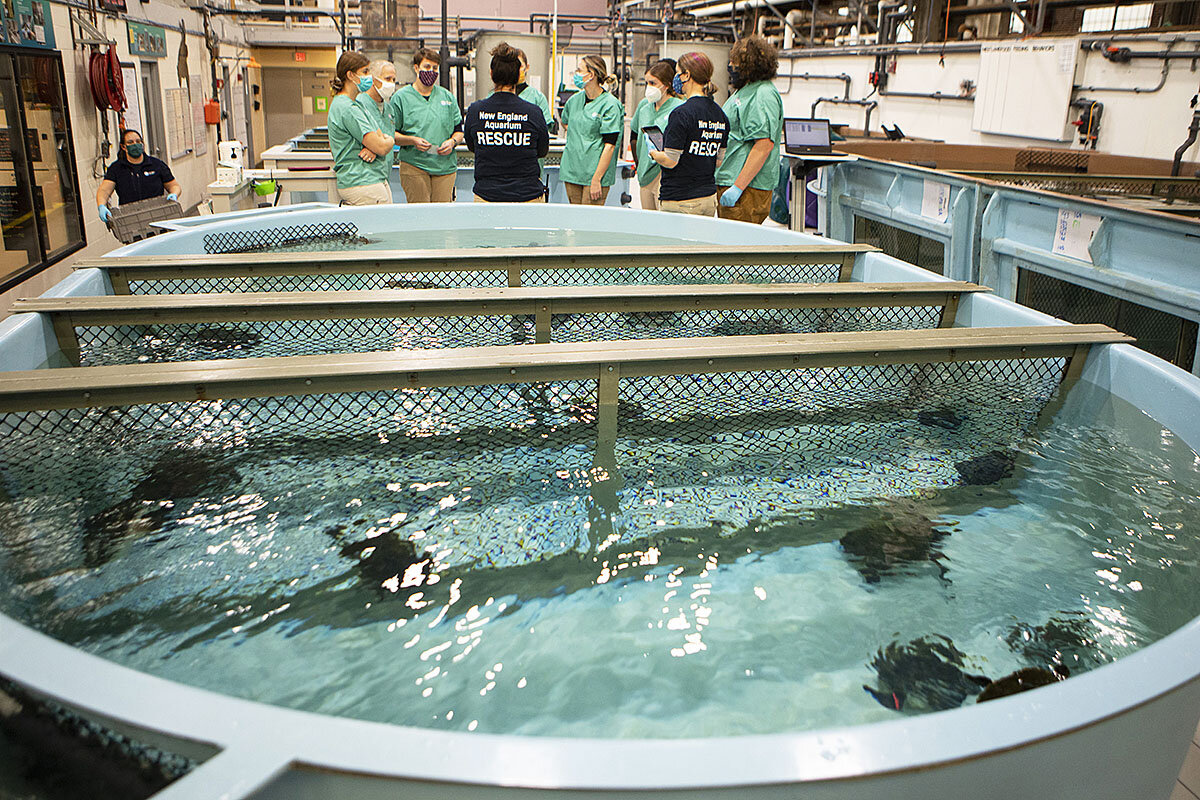

Once the turtles are stabilized, their next stop is the New England Aquarium’s Sea Turtle Hospital in Quincy, Massachusetts, a cavernous space filled with multiple pools, expert staff, and lots of volunteers. Each turtle is given a thorough physical examination, and soon they are placed in temperature-controlled pools where their behavior is closely monitored. If all looks well, they continue their journey on charter flights south to secondary rehabilitation centers. The healthiest will eventually be released back into their ocean home.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct a misidentification of Karen Dourdeville's expertise. She is a marine biologist.