Tapped out: An Arizona community symbolizes West’s water woes

| RIO VERDE FOOTHILLS, Ariz.

The American Southwest is struggling for a new balance on water use.

As the region enters its 23rd year of drought, the federal government has told the seven Colorado River Basin states to agree on how to reduce by one-fifth the amount of water they withdraw from the river. So far, the states have missed deadlines to do this.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn the American Southwest, people are having to conserve water as never before – from states wrangling over the Colorado River to one small Arizona community where a key source just dried up.

Cities are seeking their own strategies, including plans to allow for continued development in what is one of the fastest-growing regions in the United States.

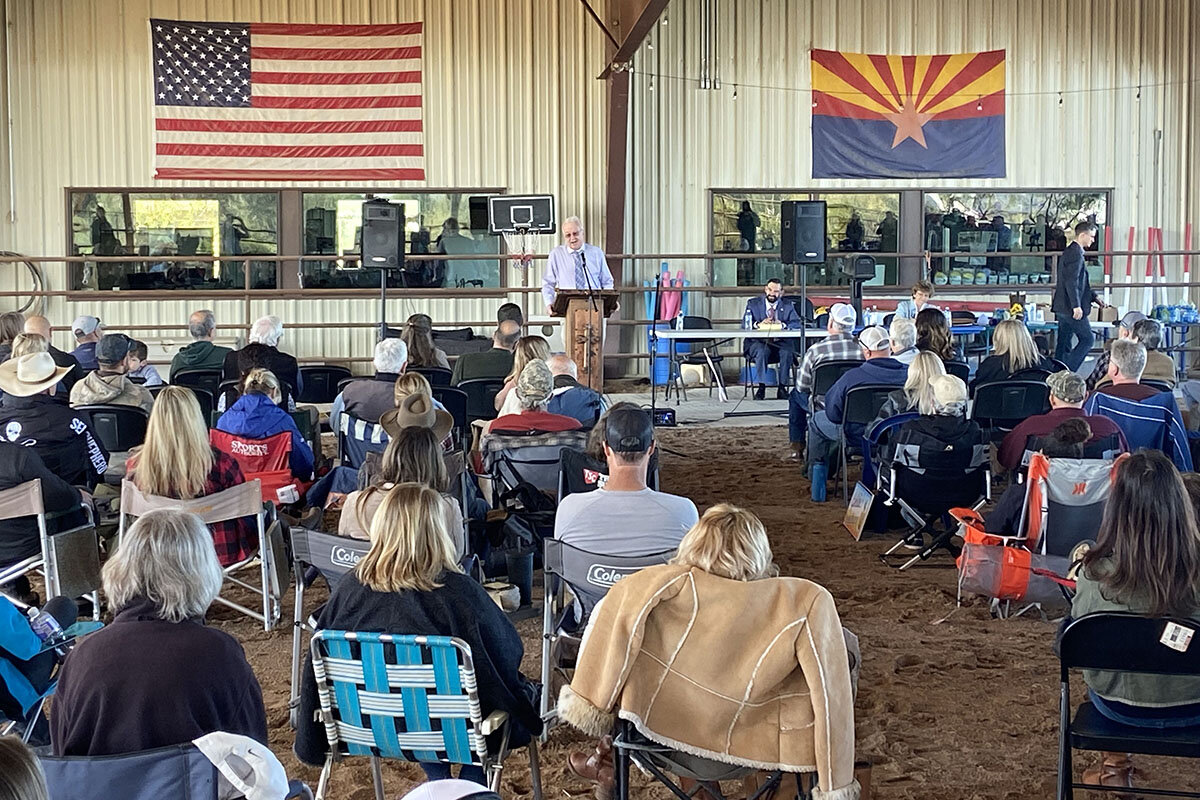

But for a symbol of the challenge, consider Rio Verde Foothills. This unincorporated community has been built largely through what is known as wildcat development, a subdivision strategy that can skirt a state law requiring proof of water availability. Many residents rely on wells or on water trucked in from Scottsdale nearby. Now, Scottsdale, citing its own needs, has halted the water exports.

Regina Raichart, a horse trainer in Rio Verde Foothills, has relied on hauled water for her small home and has long tried not to be wasteful. To her, Scottsdale is being unreasonable, and the cost of hauled water is going up.

“We’re not asking anyone to give us water for free,” Ms. Raichart says. “I’m not expecting a handout.”

It was never a secret that the water situation was complicated.

There is no municipal water supply in this 18-square-mile flatland of dirt roads, ranches, and dun-colored homes. Indeed, there is no municipality at all here, which has been part of the attraction for many of the people who have moved to Rio Verde Foothills, an unincorporated community northeast of Phoenix.

To survive in this sunbaked swath of central Arizona, people either sank wells or paid for regular truck deliveries of water from the nearby city of Scottsdale.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onIn the American Southwest, people are having to conserve water as never before – from states wrangling over the Colorado River to one small Arizona community where a key source just dried up.

“We’re off the grid,” says Tom Braun, a retired oil industry employee who three years ago paid $681,000 for a 3,600-square-foot house on 2 1/2 acres here. He and his wife, who appreciated the open skies and lack of city taxes when they decided to relocate from Houston, have a 10,000-gallon cistern under their home to store hauled water. “We live out here to stay as far away from the government as possible.”

But, as it turned out, the government would still have a huge impact on Mr. Braun’s life.

As the southwestern United States enters its 23rd year of drought, and as the Colorado River and connected reservoirs sink to unprecedentedly low levels, the federal government has told the river’s seven basin states to agree on how to reduce by one-fifth the amount of water they currently withdraw. So far, the states have been unable to do this, on Jan. 31 missing yet another deadline to turn in recommendations.

State governments, meanwhile, have recognized that cuts are likely in some form and have been working to balance the water needs within their borders. In Arizona, cities have also come up with their own water strategies, which they hope will both help with adjusting to expected new restrictions and allow for continued development in what is one of the fastest-growing regions in the U.S.

And in Scottsdale, the official water management plan this year included something that many of the residents of Rio Verde Foothills did not believe would happen: The city, in effect, turned off the community’s water.

Rapid growth, tightening spigots

The supply of Scottsdale water to the residents of Rio Verde Foothills had long been tenuous, even if homeowners didn’t recognize it.

Scottsdale is one of the most rapidly growing cities in the U.S., and for years has warned that it would eventually cut off the water supply going to homes outside its borders – part of an effort to balance its water conservation and reclamation initiatives. Last year, it announced again that it intended to stop letting haulers fill up at public standpipes as of Jan. 1.

At the beginning of this year, it followed through on that threat. This meant that 500 or so homeowners needed to get their water from somewhere else.

For the Brauns and many others, this has meant paying hundreds of extra dollars each month for the same number of gallons of water, since suppliers cannot source the water from Scottsdale. It also means anxiety for homeowners who didn’t fully realize the tenuousness of the tap.

“Most of these new people are from out of our state, and they don’t know any better,” says Christy Jackman, who has lived in the community for 13 years and has her own well. Earlier in the day, she’d taken a call from a panicked woman who closed on a hauled-water house a month ago and hadn’t heard about Scottsdale’s cutoff. “Our realtors haven’t been honest and our builders haven’t been honest.”

Although Arizona law requires developers to prove that any new homes would have 100 years of water availability, there is an exception for landowners who split parcels into fewer than six lots. This has brought about what’s called wildcat development, a sort of subdivision strategy that can skirt regulations. Rio Verde Foothills falls into this category.

But water experts say these wildcat developments, along with individual homeowners who simply rely on their own well water, are on a collision course with the ecological reality of the state.

How warming temperatures affect water supplies

Arizona, like the rest of the southwestern U.S., is in the midst of a drought that began in 2000. Although scientists believe the region has experienced long dry spells before, the current situation has been exacerbated by global warming and temperatures in the region that, for the past 22 years, have been consistently – and often significantly – above average.

“The drought itself would hardly be considered a drought if it were not for the human-caused component of increasing temperatures,” says Christopher Skinner, an assistant professor of environmental, earth, and atmospheric sciences at the University of Massachusetts Lowell.

This is because hotter temperatures in the air mean more evaporation on land, both from rivers like the Colorado and from soil itself. Drier soil, meanwhile, absorbs more heat, creating a sort of heating feedback loop.

The Colorado River – a key water supplier for Scottsdale and other cities throughout its basin, not to mention the source of vast amounts of irrigation water for agriculture – is at its lowest level in a century. The water levels along the river in Lake Powell and Lake Mead, the country’s two largest reservoirs, have dropped so low that officials are worried they could reach “dead pool” – the name for what happens when there’s not enough water to flow past the dams. In the case of Lake Mead, this could mean no water going over the Hoover Dam, which in turn would stop most of the water going into cities like Los Angeles, and agricultural centers such as the Imperial Valley, which grows much of the country’s food.

“This isn’t hyperbole,” says Jeffrey Silvertooth, a soil agronomist with the University of Arizona’s department of environmental science who works as an extension agent with state farmers. “This isn’t drama that’s being drummed up for media coverage. The river is maxed out.”

A pivot in Scottsdale

Cities like Scottsdale have known they need to find a way to balance existing water use with growing development. In recent years, Scottsdale officials have developed a water management plan that relies on both conservation and reclamation initiatives, including a massive water treatment facility, says Sarah Porter, director of the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University.

But those initiatives don’t work if there’s just a flow leaving the system – like the water going to Rio Verde.

“Scottsdale has invested a whole lot of money in a treatment plant,” she says. “But they can’t reclaim Rio Verde water because everyone is on a septic. They had a leak in their very good water management system, and that leak was called Rio Verde water hauling.”

And so, to maintain the balance, it was necessary to shift policy.

“It’s a really understandable move by Scottsdale,” she says.

But as with all water decisions in the West, creating balance does not mean that everyone leaves happy. Balancing a dwindling resource means that all constituents are going to get less – and some might get way less.

This, essentially, is what the Colorado River Basin states are arguing over: the legal and practical considerations on who has to make the most cuts to their water, and in what order. The U.S. Department of the Interior, whose Bureau of Reclamation oversees the country’s waterways, has asked the seven states in the Colorado River Basin – Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Arizona, and California – to jointly recommend new cuts to the water they take from the river, which would then guide new federal regulations.

But there is continued disagreement between California and the other six states over who should make cuts first, and by how much. While there is a century of legal code – collectively called “the law of the river” – that theoretically governs Colorado River water usage, the states disagree about how to interpret it, and how closely century-old laws should govern a present altered by climate change.

Meanwhile, the water levels continue to sink.

“There’s drought, climate change, overuse,” says Robert Glennon, a law professor at the University of Arizona who is the author of “Unquenchable: America’s Water Crisis and What To Do About It.” “We’ve been using more water than there is water in the river. And at some point, this was going to come and bite the states on the big toe.”

“I’m not expecting a handout”

But on the micro-local level, the changes in water access can seem sudden.

Regina Raichart is a horse trainer who works on a ranch in Rio Verde Foothills. Five years ago, she bought a 1,100-square-foot home for $250,000 where she lives with her four dogs. She relies on hauled water.

“I knew [about Scottsdale's threat]. But it had been such a long-standing practice. ... I really didn’t think” it would end, she says.

She worries about higher future costs for water. She already tried not to be wasteful.

“I always conserve water. I have got great respect that we’re in the desert.”

Now she takes shorter showers and doesn’t water the landscaped yard.

She argues that Scottsdale is being unreasonable in not allowing haulers to use its standpipe for water that is coming from other sources.

“We’re not asking anyone to give us water for free. I’m not expecting a handout.”

Ms. Jackman, for her part, worries what might happen to her well water supply. Across the street from her, 17 new homes have gone up in the last two years. Builders have sunk new wells, and like many residents, she worries about the impact on existing ones.

Still, there is nowhere else she would rather live. She keeps horses and donkeys on her property, and loves that nobody will complain about the noise of braying. She loves the flora around her: cholla cactuses, prickly pear, yucca, mesquite, paloverde. She loves summer storms, watching lightning over the mountains.

The water crisis has prompted her to become active in the community: She has opened a Facebook page for residents and has contacted lawmakers, pushing for a new sort of balance that maintains her community.

“It’s a place that fills your heart up,” she says.