California wildfires rage, forcing evacuations. How warm winds stoke risks.

| Pasadena, Calif.

The Los Angeles region is experiencing severe wind and fire danger this week, with gusts sweeping through a highly populated area that is exceptionally dry for this time of year.

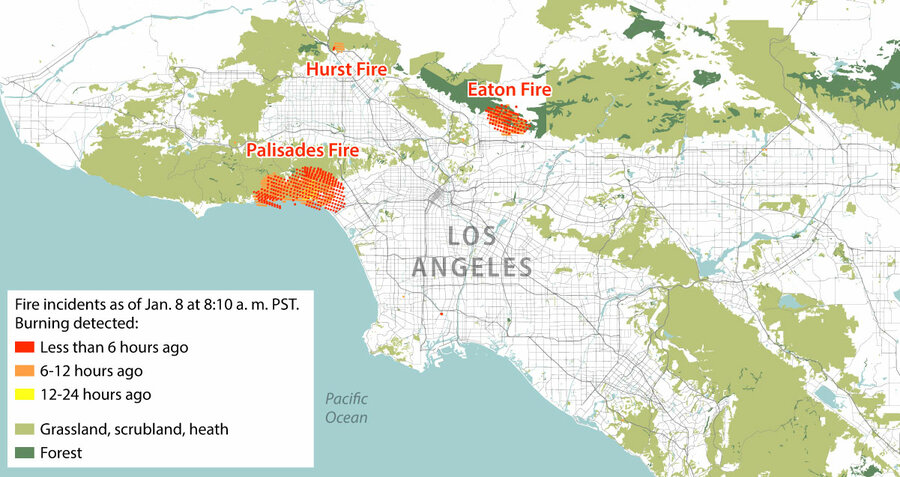

By Wednesday morning, three major wildfires were burning in and around Los Angeles, consuming a total of 7,500 acres – and growing. Gov. Gavin Newsom has declared a state of emergency and deployed 1,400 people to assist the firefighting. More than 80,000 residents have already been displaced by evacuations, and 70,000 are without power. Schools are closed.

Why We Wrote This

Thousands have evacuated as wildfires threaten populated areas near Los Angeles. Gusty Santa Ana winds are familiar in the region, but this week’s weather comes amid a dry start to what is typically the rainy season.

Residents of Southern California are familiar with these gusty Santa Ana winds that can tear through the region in cooler months. But this week’s weather event is particularly dangerous because it comes amid a dry start to the rainy season.

“This is one of the most powerful wind events of the season. Although it is occurring in the heart of what is normally our wet season, we have had no significant precipitation to shut off its ability to spread wildfire quickly,” said Alex Hall, director of the Center for Climate Science at the University of California Los Angeles, in a statement.

The Los Angeles region is experiencing severe wind and fire danger this week, with gusts sweeping through a highly populated area that is exceptionally dry for this time of year.

By Wednesday morning, three major wildfires were burning in and around Los Angeles, consuming a total of 7,500 acres – and growing. Water is a challenge here, as the urban infrastructure is being pushed beyond its limits, with some hydrants in Pacific Palisades being reported as dry. Crews are stretched, too, as they face the extraordinary challenge of multiple large fires burning at once.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has declared a state of emergency and deployed 1,400 people to assist the firefighting. At least two people have died, and more than 1,000 structures have been destroyed, according to Los Angeles County officials. More than 80,000 residents have already been displaced by evacuations. Some 70,000 are without power. Schools are closed.

Why We Wrote This

Thousands have evacuated as wildfires threaten populated areas near Los Angeles. Gusty Santa Ana winds are familiar in the region, but this week’s weather comes amid a dry start to what is typically the rainy season.

The Palisades fire started Tuesday and moved rapidly through the hilly Pacific Palisades neighborhood, home to many celebrities. Portions of the Pacific Coast Highway and Interstate 10 were closed to all but locals to help with evacuation.

The wind event is expected to last for several days and gusts were forecast at up to 100 mph. It could be the strongest Santa Ana windstorm in more than a decade, according to the National Weather Service.

Why are these winds particularly dangerous?

Residents of Southern California are familiar with these gusty Santa Ana winds that can tear through the region in cooler months. Dry and warm, they originate inland and push with ferocity over mountains and through narrow canyons to the coast, stoking sparks – from downed power lines, for instance – into a rapidly moving fire. But this week’s weather event is particularly dangerous because it comes at a time of a dry start to what is typically the rainy season here.

“This is one of the most powerful wind events of the season. Although it is occurring in the heart of what is normally our wet season, we have had no significant precipitation to shut off its ability to spread wildfire quickly,” said Alex Hall, director of the Center for Climate Science at the University of California Los Angeles, in a statement.

This is not like a more typical Santa Ana event where it’s windy in the mountains and fairly calm in the highly populated valley areas, said UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain in a webinar with reporters on Monday. “It will be quite a widespread event” covering a large swath of Southern California and going for several days, he said. Strong upper-level winds are aligning with surface winds to produce what he called an “atmospheric blow-dryer.”

Dr. Swain also warned of “mountain waves.” When wind hits mountains – and Los Angeles sits at the foot of the Santa Monica and San Gabriel Mountains – it gets pushed up in a wave. That wind can bounce around up above when the atmosphere is more stable, or, in this case, it can be forced down the other side, sweeping along foothills and into populated valleys, producing windstorms that accelerate conflagrations. This phenomenon fueled the Lahaina Fire in Hawaii in 2023 and the Marshall Fire in Colorado in 2021, he said.

What happened to California’s wet season?

The rainy season can run from October to April. It’s alive and well in Northern California, which has already seen heavy rain and snow in recent months. But the southern part of the state has seen nary a drop, and in many parts of the Southland it’s the driest start to the season on record, according to Dr. Swain. This makes for bone-dry conditions. Statistically, February is the wettest month in the Golden State. But February is still weeks away, and there is no rain in the immediate forecast for Southern California.

Does climate change play a role in this event?

Not as it relates to the Santa Ana winds, say climate scientists. Interestingly, climate change could potentially cause fewer and less severe Santa Anas, says Paul Ullrich, a professor of regional and climate modeling at the University of California Davis. “Santa Ana wind events are one of the few phenomenon where we actually expect them to weaken,” he says.

Where climate change does play a role is in “weather whiplash” – when weather shifts from one extreme to another. The past two California winters were unusually wet, including severe flooding. That fed an explosion of vegetation growth. Last summer, though, saw record heat in California, followed by the non-start of the rainy season in the south. Hence, this week’s tinder box.

“One of the biggest consequences of climate change is increases in variability. That’s a fancy way of saying that extreme conditions tend to become more common, and kind of average conditions become less common,” says Professor Ullrich.

How did local officials help residents prepare?

Ahead of the windstorm, fire crews were mobilized to the highest-risk areas, and utility companies deployed crews to monitor neighborhoods for electrical hazards. Red Flag warnings are in effect throughout Los Angeles County, restricting traffic and parking. Firefighters are being called in from across California to aid the insufficient number of personnel already on the ground.

Staff writer Ali Martin contributed to this report from Los Angeles.

Editor's note: This article was updated on Jan. 8, the date of initial publication, including with clearer characterization of the fires and information on fire-safety preparations.