The Keystone XL pipeline is irrelevant

Loading...

Keystone XL’s Insignificant Contribution to Climate

Last month President Obama unveiled a new plan to combat climate change in a speech at Georgetown University. While there is generally broad consensus that his comments further threaten the already battered US coal industry, his comments on TransCanada’s (TSX: TRP, NYSE: TRP) Keystone XL pipeline project had pundits guessing at his meaning. Here is what the President said in his speech about Keystone XL:

Now, I know there’s been, for example, a lot of controversy surrounding the proposal to build a pipeline, the Keystone pipeline, that would carry oil from Canadian tar sands down to refineries in the Gulf. And the State Department is going through the final stages of evaluating the proposal. That’s how it’s always been done. But I do want to be clear: Allowing the Keystone pipeline to be built requires a finding that doing so would be in our nation’s interest. And our national interest will be served only if this project does not significantly exacerbate the problem of carbon pollution. The net effects of the pipeline’s impact on our climate will be absolutely critical to determining whether this project is allowed to go forward. It’s relevant.

The reason that there have been widely differing views on the President’s intentions boils down to his use of the phrase “only if this project does not significantly exacerbate the problem of carbon pollution.” The State Department’s Draft Supplementary Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS)for the Keystone XL Pipeline project already concluded that approval of the project would have little impact on global carbon dioxide emissions or on the development of the oil sands because of their view that the oil will get to market one way or another. More on that below.

My own position is that it doesn’t matter whether the pipeline is built, because I also think — for reasons I detail below — that the project will make no measurable contribution one way or another to the global climate. In my opinion, after digging through the data I believe that the pipeline is irrelevant as far as the global climate is concerned. In fact, I will demonstrate below why I believe that this is so. The only reason I care at all about this issue — as I explained in Protesting Keystone XL While Rome Burns — is that I think it is a misallocation of resources when we don’t have time to misallocate resources. It also conveys a false impression of the most important drivers of global carbon emissions.

Let’s first use a bit of science and data to see what the numbers imply about the significance of Keystone XL — even for a worst case scenario. Here’s a 3-step exercise that anyone can do to estimate the impact based on specific sets of assumptions:

- State your assumption of how much oil that you believe Keystone XL will facilitate being burned that wouldn’t be burned otherwise. You can make that number as high as you like, but state your reason for choosing the number.

- Calculate the expected global temperature impact that would arise from your number.

- Finally, calculate the length of time it would take to burn the amount of oil you chose in your first step. How much would the global temperature be expected to have changed 50 years from now in your scenario? (Information cited below will allow you to calculate Steps 2 and 3).

For me, the calculations look like this.

For Step 1, the pipeline itself would transport 830,000 barrels per day (bpd) at maximum volume. I would certainly expect this volume to displace some other oil from the market such that the entire 830,000 bpd is not a net addition to the global oil market. However, the climate impact of even the total 830,000 bpd is trivial. It less than 1/10,000th of a °C per year.* This contribution wouldn’t even be measurable. It would merely be noise in the global temperature measurement.

So, that clearly wouldn’t get anyone excited, therefore one has to begin extrapolating. What if the pipeline was the catalyst for extracting the entire Athabasca oil sands reserve in Alberta? Well, that’s still not much to get excited about. For Step 2, I refer to a 2012 paper by Neil C. Swart and Andrew J. Weaver from the School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, University of Victoria published in Nature Climate Change. The reserve itself — that is the part that is economically viable to extract — is 170 billion barrels. Using standard climate models, the researchers calculated that burning the proven reserve would lead to a global temperature increase of 0.02°C to 0.05°C. That is between 1/50th and 1/20th of a degree Celsius. Not only is this still only noise in the global temperature measurement data, but now the amount of time it would take to burn through this reserve becomes relevant (which is Step 3).

But before we calculate the time to burn through the reserve, let’s look at the worst possible case that I frequently see pipeline opponents cite (with no caveats attached to it). What would be the temperature impact if the entire 1.8 trillion barrels of oil in place could be burned? This is a ridiculous assumption for several reasons, but let’s work through the case anyway. The researchers in the previously-cited paper in Nature Climate Change calculated that burning the entire 1.8 trillion barrels of oil in place could raise global temperatures by 0.24 to 0.50°C. Guess which number Keystone XL opponents like to cite? 0.5°C, the high end of the worst case, most unrealistic scenario (it’s technically impossible to burn through all the oil in place).

Besides the fact that it’s ridiculous to associate the Keystone XL pipeline with burning all the oil in place in the Athabasca, once we work through Step 3 even this worst case falls apart. Always overlooked in this debate is the length of time it would take to burn through the reserve, or the resource. The fact is that there is a limit to how fast oil can be extracted. The Canadian oil industry has been growing, but at the current production rate of 1.8 million bpd of oil sands production it would take 259 years to burn through the reserve, and 2,740 years to burn through the resource.

But let’s assume that Canada’s oil sands industry continues to grow — and despite the challenges of dealing with Alberta’s harsh winters, it manages to reach the 10 million bpd level of Saudi Arabia. Over the past decade Canada’s oil sands’ industry has grown at a rate of 8.9% per year. If that impressive rate could be maintained, Canada would reach 10 million bpd from the oil sands in 20 years. (Of course the same people arguing for this possible huge temperature effect would argue that there is no possible way to transport that much crude from Alberta). If they could then maintain that level of production, it would take Canada 57 years to extract the 170 billion barrel reserve and contribute the aforementioned 0.02°C to 0.05°C of warming to the atmosphere. So, in making a number of stretch assumptions, if the Keystone XL pipeline allows the extraction of the entire Athabasca reserve, in 57 years it will have made a contribution to the global climate that is too small to be measured.

If we make one final stretch assumption and say the Keystone XL enables the extraction of all the oil in place in the Athabasca, then using the same assumptions as in the previous paragraph it would take 502 years to extract all of the oil in place and contribute the 0.5°C that pipeline opponents throw around as some sort of reasonable assumption on the expected impact the pipeline could make toward the climate. Yet in this case it would still be over a century before any impact could even be measured. Most climate activists I know don’t believe we have 100 years to solve this problem, yet time and resources are being spent on a tiny contributor to the overall problem that won’t make a measurable contribution for over a century — if ever.

At this point, some Keystone opponents will argue “Yes, but this could be the beginning of a social change that could make a difference.” But I have yet to see anyone detail how that might work. The vast majority of the world’s growing carbon emissions are coming from Asia Pacific. The reason they are growing is because billions of people aspire to a standard of living that still pales in comparison to Western standards of living. If I could connect the dots to how outrage over a pipeline from the oil sands to the US translates into a reduction of coal usage in Asia Pacific, I would concede the point. But thus far, I haven’t seen anyone connect those dots.

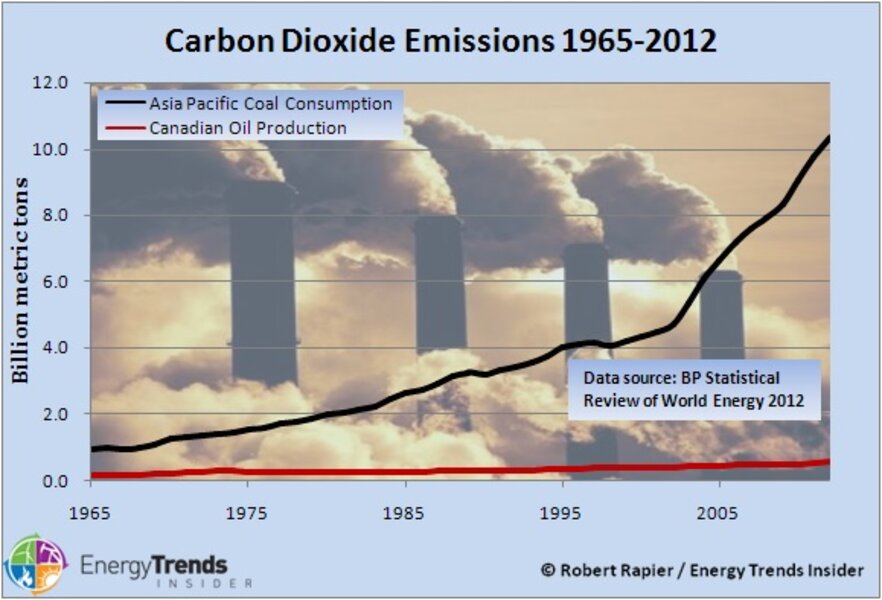

The following graphic illustrates what I consider to be the real problem, and why I consider the focus on Keystone XL to be seriously misplaced. This graphic (see figure 1 at left) shows the carbon dioxide emissions resulting from coal consumption in the Asia Pacific region, compared to the carbon dioxide emissions that would result from burning 100% of Canada’s oil production.

In this section, I attempted to show why I think Keystone’s potential contribution to the climate is insignificant. Jesse Jenkins has also performed extensive calculations on this in Climate Change and Keystone XL: The Numbers Behind the Debate. He looked at three possible scenarios involving Keystone XL and how those might impact upon carbon emissions. I think he does a great and very detailed job, but I would add that it is important to keep in mind that all of this carbon can’t be burned overnight.

The time element is one that I feel pretty much everyone overlooks. Climate change activists argue that we are in an emergency situation. But in an emergency situation, you don’t spend your time and energy on things that might have a tiny impact a century from now. Your greatest focus should be on those that can address the emergency as quickly as possible.

In the next section, I explain why I feel that even though the potential climate impact is insignificant, Keystone XL is irrelevant in any case.

Why Keystone XL is Irrelevant

One of the contentious issues in the debate over the Keystone XL pipeline is whether the oil from the Alberta oil sands will get to market even if the pipeline isn’t built. “The rail system doesn’t appear to be capable of moving Keystone XL volumes” is a popular claim among Keystone opponents. When I ask why they believe this, the response I get is generally based on anecdotes by oil companies and pipeline companies, for instance, suggesting that the pipeline is an absolute necessity in ramping up oil sands production. Or, they argue that rail is simply too expensive to be an alternative method of transport. This is a perfect example of a theory being directly contradicted by data.

In the US and Canada we have already seen oil transport by rail increase by about one million barrels per day (bpd) over the past 5 years. This scale-up is greater than the 830,000 bpd the Keystone XL would transport at full capacity. Bakken oil is now being railed to refineries on the East Coast, West Coast, and Gulf Coast – and if you listen to the earnings calls or investor presentations from various refiners, they plan to continue expanding this practice. Four years ago there was essentially no oil being shipped by rail from the Bakken. Two years ago, approximately 50,000 bpd was being shipped by rail. Today that number is 640,000 bpd — 71% of the crude oil production in North Dakota — and rising rapidly.

There is nothing special about the US rail system that enabled it to ramp up the transport of crude oil so rapidly. It simply responded to demand as Bakken production exploded and oil producers sought access to lucrative and distant markets. The reason is not — as some Keystone XL opponents have claimed — because there is anything special about the light oil from the Bakken that makes it easier to transport. The reason simply comes down to the differentials (as explained below).

Five years ago, these arguments could have been just as easily applied to the Bakken: production would be constrained because there was simply no way rail could ramp up fast enough to move the Bakken crude out of North Dakota. And of course shipment by rail would be too expensive. Yet it did ramp up, because the explosion in production depressed the price of Bakken crude relative to more widely traded waterborne crudes like Brent, and this created a tremendous incentive for refiners to move that product to coastal refineries one way or another.

As pipeline routes reach capacity, the decision to move by rail comes down to three factors: 1). The cost of rail shipping; 2). The price of crude oil at the destination, and; 3). The differential in the price of crude at the origin and the destination. The Bakken-Brent differential averaged about $20/bbl in 2012. According to a recent investor presentation from Valero (NYSE: VLO), the company can ship Bakken crude by rail to the West Cost for $9/bbl, to the East Coast for $15/bbl, or to the Gulf Coast for $12/bbl. This is the reason crude transport by rail in the US has exploded. Yes, shipping by pipeline is less expensive, but shipping by rail is still economical at such a wide Bakken-Brent differential.

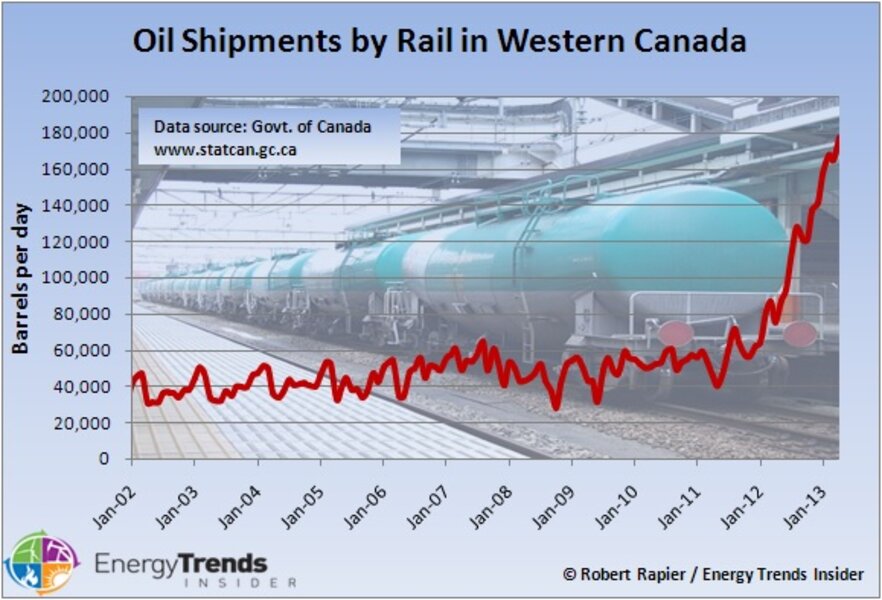

The future of oil sands development depends not on whether Keystone XL is approved. It depends on a sustained high price for waterborne crudes. With heavy Canadian oils trading at a greater than $40/bbl discount to Brent in 2012, it’s no wonder that rail transport of oil in western Canada is also skyrocketing. Over the past two years — from the April 2011 through April 2013 — the volume of oil shipped by rail in western Canada nearly quadrupled, rising from less than 46,000 bpd to more than 177,000 bpd.

Transport of heavy oil from the oil sands is expected to increase by another 60,000 bpd this year. If the differential remains high, expect the growth rate to be high, as it was in the Bakken. (I am unaware of anyone predicting 5 years ago the extent to which oil would be moved by rail from the Bakken, but the Bakken-Brent differential was very high and drove investment decisions).

As a result, Canadian rail companies like Canadian Pacific Railway (TSX: CP, NYSE: CP) and Canadian National Railway (TSX: CNR, NYSE: CNI) are turning in the best quarterly results in their histories. They are investing capital in expanding their crude oil transport capabilities. Analysts expect this trend of oil via rail to continue, with estimates that 10% of Canada’s oil production will be transported by rail by 2015.

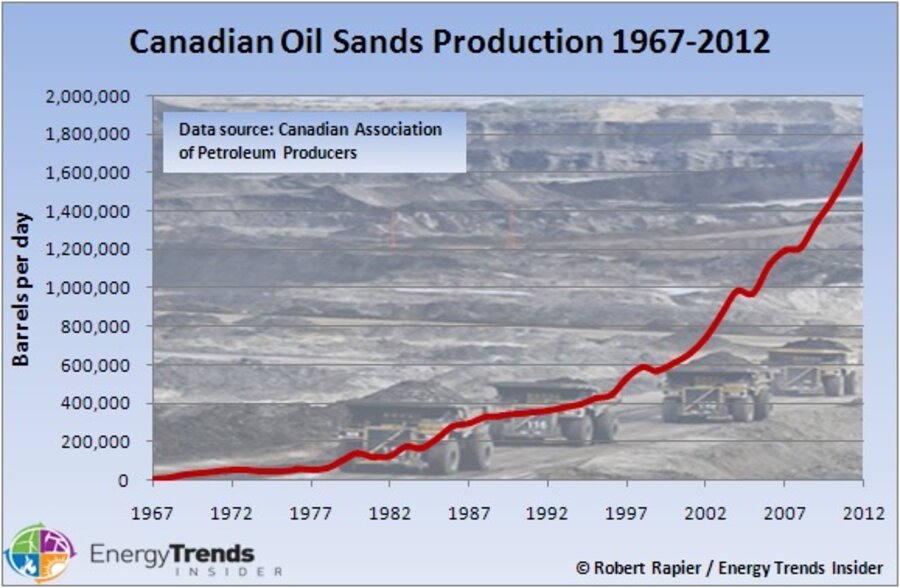

Logistical constraints haven’t thus far prevented oil sands production from growing exponentially for the past two decades. In just the past 10 years, Canadian oil sands production has grown by 1 million bpd. This didn’t happen because Canada had a million barrels of spare pipeline capacity 10 years ago. It happened because many logistical projects were executed as production increased.

As we have already seen in the development of the Bakken in the US — and in the rapid rise in rail transport of oil in Western Canada over the past two years — if the price is right the oil will find its way to market. Logistical problems get solved when the price of oil is high enough. I believe this is the single biggest oversight of protesters who believe that by shutting down Keystone they will stall development of oil sands.

One variant of the argument against rail replacing Keystone XL has been to look at only the oil flowing from Alberta to the Gulf Coast. Since that is a much smaller number than what the Keystone XL would transport, the argument is that rail is therefore simply incapable of replacing Keystone XL. That misses a very important point, because it only counts oil that is getting to the Gulf Coast. Oil that is transported by rail to a Midwestern or West Coast refinery — possibly backing out crude being piped up from the Gulf Coast, wouldn’t be counted in this scenario. But it’s not that the oil must flow to the Gulf Coast. It must simply flow far enough from Alberta to make it economical to ship it. Refiners all over the US are installing heavy crude capabilities, and rail can (and does) move this crude from Alberta to those facilities.

Conclusions

To conclude, in discussing this issue with people I feel that many have a comic book view of oil markets and the oil industry. Things aren’t static. Insufficient heavy oil capacity today can change in a short period of time if the economics warrant that. A million barrels of oil can be transported by rail in a few short years if the economics favor that. For more insight into this, see this excellent article by Peter Tertzakian (author of A Thousand Barrels a Second) on Why markets don’t watch pipeline debates.

Price will be the determining factor here, or more correctly the difference in price between what producers can get for their crude oil locally in Alberta versus what they can get if they can transport it to a coast. If that differential is high enough, you will see continued explosive growth in rail traffic, and you may even see convoys of 200 barrel tanker trucks headed from Alberta to Canada’s West Coast.

If, on the other hand, the global price of crude oil falls and remains depressed for years, that would put the brakes on the growth of the oil sands industry. I believe that even though we may see some weakness in the short-term, there won’t likely be a sustained collapse in the price of oil. Thus, I believe that the rapidly growing business of oil-by-rail will continue to expand.

Calculations: * Per the paper by Swart and Weaver, each barrel of oil burned would have the impact of raising the global temperature by 2×10-13 °C. Thus, burning 830,000 barrels per day that is transported through the pipeline would raise the temperature (2×10-13 °C) * (830,000 bpd) * (365 days/yr) = 0.00006 °C per year. At that rate, it would take 1650 years of burning 830,000 bpd to raise global temperatures by one tenth of a degree.

Acknowledgement: I would like to thank Robert Joshi for pointing me to several valuable sources of data for this article.

Disclaimer: I do not have any financial interest in any company discussed in this article. Some who prefer ad hominem arguments to actually addressing data were falsely spreading a story that I own TransCanada stock.

Link to Original Article: The Increasing Irrelevance of the Keystone XL Debate