On the road in Texas, where oil is king again

Loading...

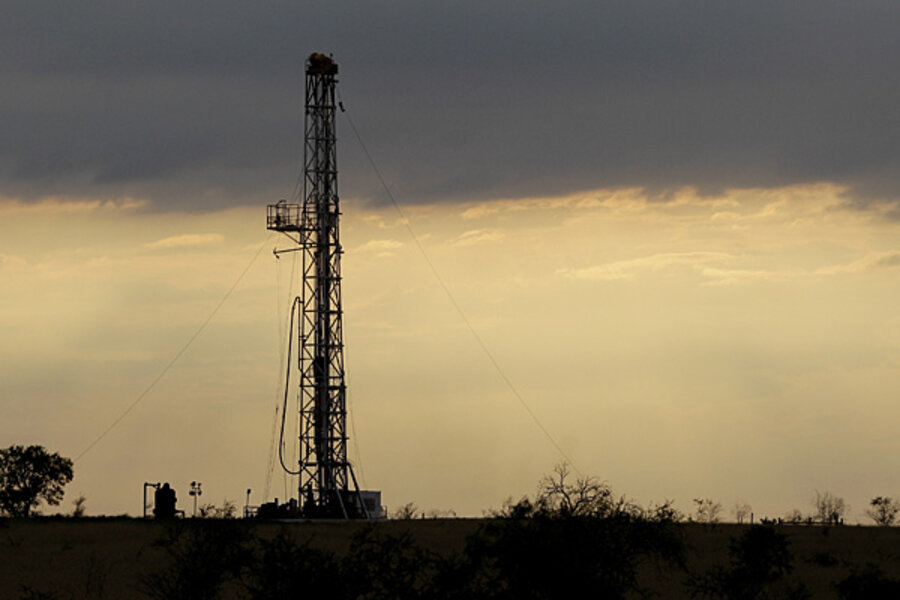

Jaunt Through West Texas Reveals Oil’s Revival

It was a 102 degree-hot, mid-July, typical summer day travelling on the road to West Texas; a nine-hour, high-speed journey made with numerous gasoline pit stops. Passing by Midland-Odessa, the commercial hub of the Permian Basin, was a stretch of energy mecca some 20 miles or more, filled to the brim on either side with oilfield services firms — transmission gear, pump equipment, fracking services, and other oil and gas-related businesses. Pumpjacks, also known as nodding donkeys, scattered across swathes of the expansive oilfields. Signs with “Home for Your Workforce” in Pecos and Odessa cropped up a couple of times. Workers, and their firms, are settling in for a boom which could last for many years to come, like the second boomlet in the 1970s and early ’80s that followed the Middle East oil crisis. Bust followed boom in Texas to the mid-1990s.

The Mega-Basin

The scale of energy production in the Permian Basin looks mammoth. The Permian Basin produced more than 270 million barrels of oil in 2010, over 280 million barrels in 2011, and 312 million in 2012. In percentages, production increased 10% in 2011 and 35% in 2012. Texas’ oil production represents about 25% of the U.S. oil production, with the Permian housing 57% of Texas’ oil production, according to the Texas Railroad Commission.

Where there are higher prices or margins possible to justify accessible resources, production will follow. The ability to recover more oil, thanks to technological advances, which include multi-stage hydraulic fracturing, horizontal drilling and carbon dioxide injection, has reversed the declining U.S. production trend of 20-years prior.

All of the large oil services firms had presences along the Midland-Odessa stretch — Halliburton, Schlumberger, Baker Hughes, and other specialist services firms like Weatherford and Key Energy Services. Don’t forget about storage, distribution and refining, courtesy of publicly-traded, master limited partnership Plains All American Pipeline and Alon Partners’ Big Spring refinery, naming just the most visible energy landmarks captured while driving 75-80 miles per hour. In 2003, roughly 3,000 new permits were issued for drilling; in 2012 there were over 9,000 issued. That’s a 300% increase in new permits issued over the decade.

Crude oil is one of the most active, vital, globally traded commodities in existence. The global energy supply chain for crude oil — its exploration, exploitation, and distribution— is one of the most complex webs of commerce. The U.S.’s revitalized production capabilities will allay some pressure from foreign imports; Nigerian and Algerian light, sweet crude imports to the U.S. have declined because of recent U.S. production. Liquified natural gas imports have trickled downward significantly owing to natural gas production gains from shale gas, from a 2007 high of 770,812 million cubic feet (mmcf) to 175,000 mmcf in 2012. The first half of 2013 looks poised for more reductions.

Increased U.S. production of crude oil is helping along the margins in the global energy market in an economic sense. However, the oil counterpart is a larger part of global interdependence in oil markets. The U.S. now becomes a more notable part of the competitive landscape for oil supply versus a price taker-only as dictated by investment, or a lack there of, or political instability in the Middle East or other OPEC nations.

The Energy Information Agency says that to meet global oil demand today “requires about one-half of the world’s supplies to be traded internationally, while about one-fourth of global natural gas supplies are traded internationally.” The energy body expects U.S. oil demand to continue falling, natural gas production to keep rising, and North America to likely transition to a net energy exporter by 2025.

Through the Aquifer

After Odessa, heading toward Pecos, Texas on a stretch of Highway 17, trucks were zooming by on Sunday even. There were signs that said “FRESHWATER” along the way and other signs with what looked like pit-lined sites of water needed for drilling. Firms with tiny storefronts like “H2Oil” were peppered here and there—wastewater disposal services. There were numerous signs with “Water for Sale”. (One wondered if the seller in fact owned the water rights and if the supply was being managed.) This stretch of the road sits atop the major Pecos Valley aquifer, where the greened, desertscapes were a surprising site, if one had ever travelled through New Mexico, Southern Colorado and other parts of the more parched lands of the West and Southwest. Water recycling and reuse of the many hundreds of thousands of gallons of water is gaining traction among producers, for reasons of economics. But the environmental and social justifications for doing so outweighs even economic arguments, especially in water-stressed regions.

The U.S. oil boom is welcome to workers left unemployed from construction’s contraction post-Great Recession and in other industries. States’ coffers are being refilled from the holes left by recession. Meanwhile, Texas and North Dakota were the two main growth-economy stories over the last few years, with GDP growth in 2012 of 4.8% and 13.4%, respectively.

The increase in U.S. oil and gas production buys some time in terms of resource scarcity and depletion concerns. Importantly, this windfall brings with it time to wisely reflect about what America’s energy landscape should look like for the generations that follow. In a twist of Texas irony, adjacent the Permian lands, was an endless stretch of wind turbines—provenance Sweetwater, Texas’ Nolan County—boasting more than 1,300 wind turbines and many more heading West.