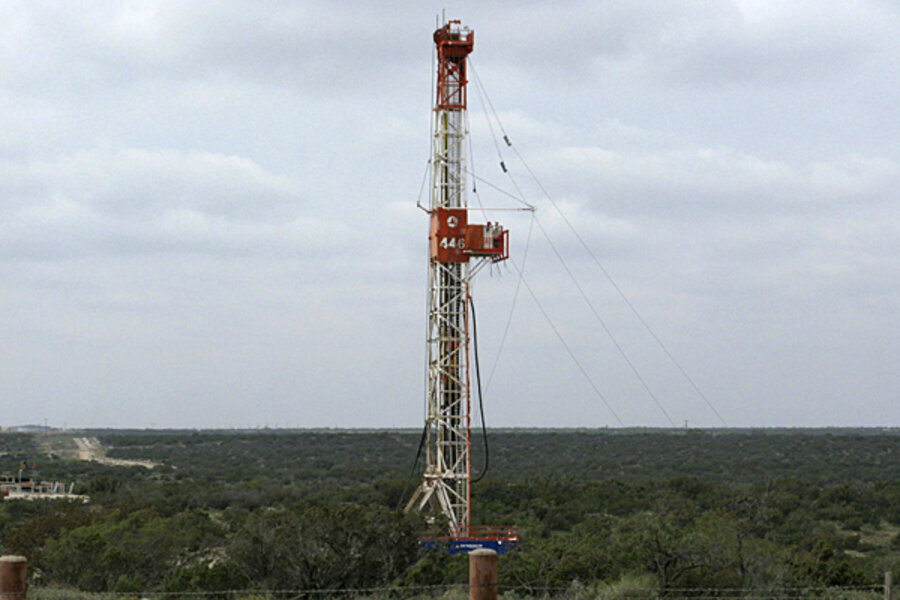

Energy disruption: Will fracking end Big Oil?

Loading...

Internationally, 2013 was the year when any doubts about shale energy potential evaporated in the face of production of both natural gas and oil in the US achieved levels that were simply prodigious. The shale “bubble” theory was beloved not only by hybocarbondhriac shale antis, but also by many in the financial community, especially in Europe. Friends of the Earth and Co may have reputational capital at stake in the energy debate, but it was the financial capital invested in not only renewable technologies but elsewhere in energy that was felt to be at risk. Thus proponents of any number of expensive energy projects fear the emergence of a world where oil and gas were not running out. Whether shale lowers prices or not is both open to question and besides the point. What shale certainly proves is that prices will not be going up.

Among other things, the shale revolution is starting to put an end to “big” energy. Nuclear, Nabucco, Shtokman, Severn Barrage and Desertec are some examples, but 2014 will start to see the unwinding of positions in other mega projects. Even some major offshore projects, and the LNG projects attached, are likely to be disrupted or postponed this year. The lesson from the USA is simple: There are hydrocarbons almost everywhere and we no longer need to go to the ends of the earth to chase them. The new energy paradigm is a world where the most attractive projects are those closest to markets. In the older “conventional” model costs and geology were paramount, and Big Oil would consider undertaking any resource project anywhere. Today, in natural gas at least, local markets are key and oil is going to go feel some of that effect. OPEC oil and Russian gas will never be unimportant, but they do have to cast off some outdated concepts around resource scarcity that they shared, often unwittingly, with Big Green. A world where oil is abundant under not only the US, but in the UK, France, Germany, Argentina and Australian sub-surface as well, makes several new off-shore projects look expensive. West of Shetland, Arctic Oil and offshore Brazil suddenly don’t seem so important anymore. Mature provinces in the North Sea and Gulf of Mexico will thrive because they have both existing take away capacity and will be able to use some tight oil technology to produce more, but gone are the days when Big Oil was desperate enough to show up in the back of beyond producing expensive oil in habitats that were environmentally fragile and politically dubious.

When capital providers say that, for example, UK oil has both physical geology and political constraints that will make the industry difficult, one has to ask the old question: Compared to what exactly? A barrier to world shale energy has been the perception that the US was the exception and the rest of the world, especially key markets such as Europe and China would be either unable or unwilling to face up to the new reality. The US shows that even a fraction of their success will be game changing world-wide.

The missing link is making shale energy acceptable to local communities and from there making shale a compelling case to local governments. Local acceptance is still an issue, and a far bigger one in the US than either Europeans or the US industry realise. But last year saw the negatives receding and the sheer size of the shale energy bounty is threatening to swamp everyone else.

Looking back at 2013, the reality didn’t start to dawn until Q2. I would date it to the sudden conversion of David Cameron, followed shortly by that of Centrica, to the reality of world shale. Despite the anti European rhetoric of the UK right, much of the credit must go to the European Commission who held an Energy Summit in May. I don’t know what they put in the Kool Aid, but Cameron came home converted, as I saw at a German Marshall Fund event that month as did almost everyone else within and without the EU. Suddenly, the shale debate had been taken away from the greens and environment and given to the grown ups in the EU Directorates General covering Industry, Economy and most of all Foreign Affairs and Security. Shale is a geopolitical movement and a financial imperative that could no longer be treated as an option. There is simply no other choice, and this choice is becoming clear not only to Europe and China but also to Russia and OPEC. When the geopolitics is in place, markets swiftly follow and Centrica was only one of several energy players eager to hop on a bandwagon they hadn't taken seriously only months earlier. International shale will break out all over, with only Shell becoming a surprising last minute waverer that may end up being a powerful enemy of shale if the policies of (early) retiring boss Peter Voser are allowed to continue. But winds are changing as we see from this report from Argentina:

Now we feel a different wind blowing and we are assessing our possibility to invest in exploring the resources,” Aranguren said. “When you reach a situation where Argentina is importing 20 percent of its energy needs, a 180-degree change is needed in the energy policy.”

We have the situation in Europe where far more than 20% is imported, even in the UK. The 180 degree change in energy policy seems is only one of several head spinning changes of energy direction down multiple blind alleys. The question in Europe will be how slow the energy revolution rolls out, not whether it happens or not. Green delaying tactics are only that. Outdated purist greens will die out or get pushed out. There’s still too much financial and political capital invested to let outdated ideas destroy all of the Green edifice. Think of this not only as a political movement, but as a business model disappearing: purists can drive what remains of the brand into a ditch, or pragmatists can rescue what they can. Some purists will linger at the sidelines of both roads and history for a few years yet, but they will be increasingly isolated and irrelevant, although occasionally dangerous to others apart from themselves.

In the UK, a flurry of reports and announcements paved the way for shale: The BGS resource estimate, Public Health England and the water industry led to unambiguous support from Davey, Fallon, Osborne and Cameron. The recent SEA and planning guidance from Owen Patterson set the stage for 2014’s big event, the opening up of onshore licensing this summer.

Let’s remember that Cameron and Centrica were still dissing shale this time last year: It would be too expensive, the geology is different and most of all, a lingering disbelief that the US shale experience was true. British people, as Gillian Tett put in the FT recently, enjoy schadenfreude at their own misfortunes. Many in the City of London, who in the best of times have an obsessive fear of failure which makes no risk at all the best option, also share much of the narrative of resource scarcity. They are also more fearful of losing money than losing the opportunity to make it. This in the FT recently this highlights the difference between the US and the rest of the world:

US venture capitalists are enthusiastic risk-takers and its capital markets reward successful companies that make it to IPOs with high ratings. The willingness to bet a lot on an untested venture is deeply rooted in the US business culture and start-ups in Europe often face a more sceptical investor climate.

An inspiring recent book has been Greg Zuckerman’s The Frackers. It’s above all the story of people who didn’t listen to conventional wisdom. UK oil and gas is under a huge market with existing infrastructure, subject to full regulatory support, and high gas prices that will continue to be at least double US prices. Oil will be an even better bet, linked to Brent. Expect this summer's UK license round to be busy with companies not scared off by conventional experts.

The conventional wisdom was wrong this time last year. By this time next year, any distinction between conventional and unconventional oil and gas may have disappeared entirely. Until then, there will be opportunities for US based funds to make money out of the UK shale revolution if European ones remain shortsighted.

US players are used to buying up acreage at thousands of dollar an acre, and add to those costs by associated landman and legal fees. That doesn’t mean success is guaranteed. Although it may seem that oil and gas is under every North American rock, there have been failures, although they were often fields with geological problems that were simply too complex to solve at the time. After getting drilling rights, US wildcatters then have to invest further millions in seismic and drilling to prove up the play. At that point they’ll have to pay up to 25% royalty to the landowner and if they’re drilling long lateral, they’ll have to do that to lots of landowners, pushing up costs further. In the UK, under the new license regime from Chancellor Osborne, they need only write only one check to the government for 30% in the exploration phase, 62% in production.

Getting a license in the UK won’t ensure instant success. We don’t yet know the licensing procedure for the next round, and it will surely be more complex and crowded than the 2008 round, where basically anyone mad enough to apply for an onshore UK license was given one. If the same procedure is replicated this time, and judging by North Sea licensing it won’t be too different, a US company could pick up 100 sqkm blocks (24,710 acres) for handfuls of pennies an acre not fistfuls of dollars.

UK fund managers too often are not risk takers but economists, and the old story is that two economists see a $20 bill on the floor and both refuse to pick it up on the grounds that it shouldn’t exist in theory. The oil and gas variation is that after drilling a successful well, all one is left with would be a hole in the ground that money flows out of. First, however, one needs to bend down. People all over the world, including some who practice tai-chi are limbering up.