How teeth may help solve a 53 million-year mystery

Loading...

Fifty-three million years ago, during the Eocene epoch, Earth was much warmer and the high Arctic was a different place. On Ellesmere Island near Greenland – now one of the coldest, driest place on Earth – temperatures ranged from just above freezing to 70 degrees F.

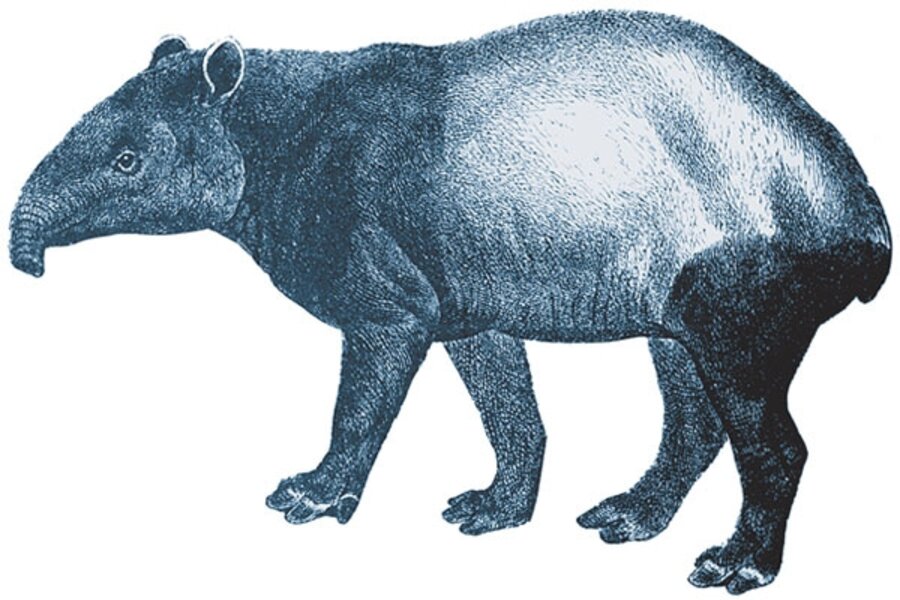

Mammals that are relatives of today’s tapirs, rhinos, and lemurs inhabited swampy forests in Greenland, which were much like those now found in the southeastern United States.

Alligators, giant tortoises, and snakes lived there, too.

Scientists have long wondered: Did these animals – some of which reached 1,000 pounds – migrate there seasonally, or did they stay year-round through the winter darkness?

Writing in the June issue of the journal Geology, scientists conclude that the mammals stayed all year.

Fossilized teeth tell the tale. Oxygen isotopes in tooth enamel hint at local seasonal changes in drinking water. The changing signature corresponds with shifts in rainfall and temperature. Isotopic carbon signatures also reveal how the animals changed their diet with the seasons. During the summer, they dined on flowering and aquatic plants, and deciduous leaves. When winter came, they switched to twigs, leaf litter, evergreen needles, and fungi.

The finding may help resolve another mystery: How did some hoofed animals migrate between continents? To do so, they had to cross land bridges that connected the land masses. The bridges were often in the Arctic.

Perhaps year-round Arctic residency is the answer, say the authors. Permanent residents could have made the long trip incrementally over generations.