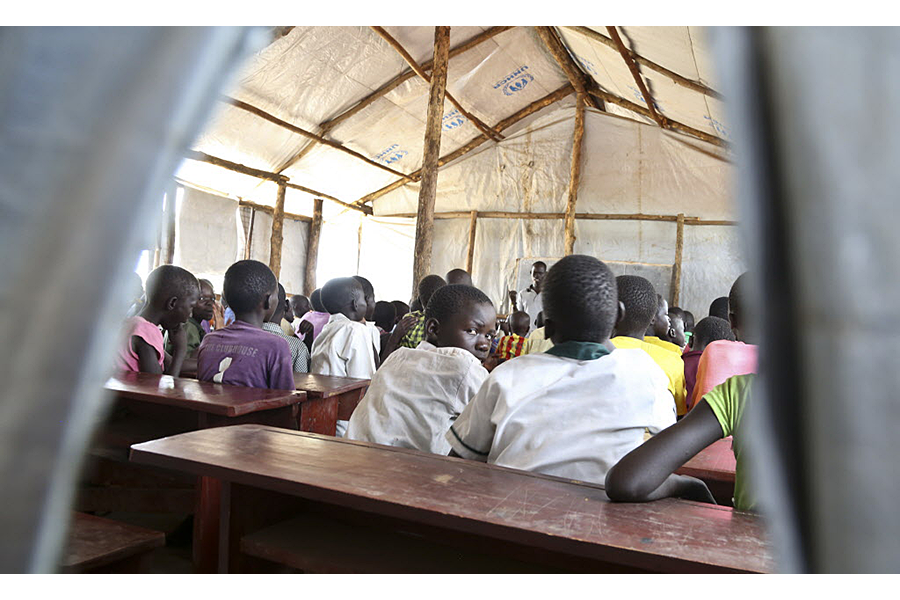

Education in South Sudan 'cannot wait,' says new report

Loading...

After decades of conflict left much of South Sudan illiterate, a new round of fighting has further compromised the young nation’s current education system.

Since the South Sudanese Civil War began in December 2013, one in three schools have been attacked by armed forces or groups, according to a report released this month by Education Cluster, a collaboration of NGOs, United Nations agencies, and academics. At the same time, one in four schools reported to be open in 2013 were found to be non-functional by 2016.

This newest report adds to documentation by the United Nations and human rights advocates of child soldiers, school attacks, and an underfunded and underserved education system in South Sudan. While the Education Cluster and other groups have met with some success intervening in schools and advocating for children, the report highlights the difficulty of providing children with education in the world’s newest country, as well as in conflict zones in general.

It's not just the children who suffer when their learning is terminated or restricted, say education advocates. An entire country – especially a fledging nation like South Sudan – will pay the price for not educating its children.

“When children don’t have access to education, it makes it that much harder for the country to develop economically,” says Jo Becker, advocacy director of Human Rights Watch’s Children’s Rights Division. “Children have fewer opportunities for decent livelihoods, and for getting decent jobs. The consequences are both for the children themselves, in terms of their inability to get ahead, but there are also consequences for the society not having an educated population than can really help it develop economically.”

Education Cluster’s report, “Education Cannot Wait for the War to End,” is the product of a national assessment it conducted of schools in South Sudan in November 2016.

The cluster found that 31 percent of schools have suffered at least one or more attacks from armed forces or groups, and 25 percent of primary schools open in 2013 were found to be non-functional in late 2016. In addition, 31 percent fewer teachers were also registered at the end of the 2016 school year than at its start.

Food shortages were one of the main reasons students dropped out or stopped attending, reports Education Cluster. The government declared parts of South Sudan had been hit by famine in February, with 100,000 of its people facing starvation, and one million more on the brink of famine, according to BBC.

But the whole crisis, warns the report, threatens another generation of South Sudanese with illiteracy, as nearly 50 percent of the its population are under 18. Because of decades of conflict between what is now South Sudan and its neighbor, Sudan, 73 percent of men and 85 percent of women are illiterate, according to government data from 2011 and 2013.

There has been some progress. Under "education in emergencies and protected crises" intervention, the cluster provides classes for children who can attend in a safe space. After that support, 4.6 percent more South Sudanese students passed end-of-primary exams, compared to the nationwide average pass rate. Egypt, Ethiopia, and neighboring Sudan have also agreed to support South Sudanese students seeking college degrees through programs like scholarships and lowered tuition rates. But these are all temporary solutions to an education system badly hurt by civil war.

The most recent conflict may have left as many as 300,000 people dead, Agence France-Presse has reported, and displaced more than 3.5 million, or more than one-fourth of the population. While the conflict has ravaged the country’s oil-dependent economy, children and schools have also been singled out as targets.

“The fabric of this whole country has been ripped apart by this conflict. Pretty much everyone is affected by this war,” Jehanne Henry, a senior researcher in Human Rights Watch’s Africa Division, tells The Christian Science Monitor in a phone interview on Monday.

Both the United Nations and other groups have found that more than 17,000 children have been used as soldiers. According to Ms. Becker, some of these child soldiers told Human Rights Watch that they took up arms because they were deprived of an education. But schools have also been either the targets of attacks or taken over for barracks, military training, or operation centers.

Another problem that has plagued South Sudan is a lack of qualified teachers, stemming from the previous 22-year conflict between what is now South Sudan and its neighbor, Sudan.

"The teachers of those years either died or they joined the [rebel] movement," Edward Kokole, director of teacher education in South Sudan's Education Ministry, previously told the Monitor.

In 2015, only one-third of South Sudan's 28,000 teachers were qualified, according to the National Ministry of Education. Now, the student-to-teacher ratio is 100 students for every qualified teacher, according to the Education Cluster report.

One problem is the lack of literate adults. But another is pay. Government school teachers earn less than fifty dollars a month, and are rarely paid on time. In 2014, salaries in some states went unpaid so the government could fund the war effort.

Overall, South Sudan has the highest rate of out-of-school children among 22 countries in conflict zones, according to the UN. Behind it are Chad and Afghanistan. On the whole, 25 million children between 6 and 15 years old are out of school in these conflict zones.

“At no time is education more important than in times of war,” UNICEF Chief of Education Josephine Bourne said in a statement. “Without education, how will children reach their full potential and contribute to the future and stability of their families, communities and economies?”