More than 'beautiful words': How one school fights to keep racial equity

| St. Louis

Ten years ago, a group of black and white parents in St. Louis realized that if they wanted an integrated school, they would have to create it themselves. A decade on, City Garden Montessori School is recognized for both its quality and its racial diversity, maintained by diligence on the part of the staff. The journey to becoming truly integrated has forced them to call upon reserves of hope, moral courage, and perseverance. About 50 percent of the school’s kindergarten through eighth-grade students are white. But its low-income population, once more than half the school, has shrunk to 39 percent. In response, the charter school formed an affordable housing task force, and it has lobbied the state legislature in the hopes that it will allow a weighted lottery to maintain a balance of low-income students. “We no longer have the privilege of pretending that race doesn’t matter,” says Nicole Evans, the school’s African-American principal. “We tell every parent that comes in: This is not just beautiful words on the wall…. This is a matter of life or death for some of our students.”

Why We Wrote This

At this Missouri school, maintaining racial parity takes vigilance. One outcome is open discussions about race – among students, parents, and staff – that reflect the possibilities of a more integrated society. Part 2 of an occasional series.

Lead “guide” Anne Lacey sits on the rug, giving a lesson to a wiggly cluster of first- to third-graders. She’s white, with wavy hair and glasses. Robert Nelson, the assistant guide (a Montessori term for educators) is folded into a tiny chair at the back of the room, checking a boy’s math, when a girl wearing a cat-eared headband pounces on him for a hug. He’s African-American, with a shaved head and black beard.

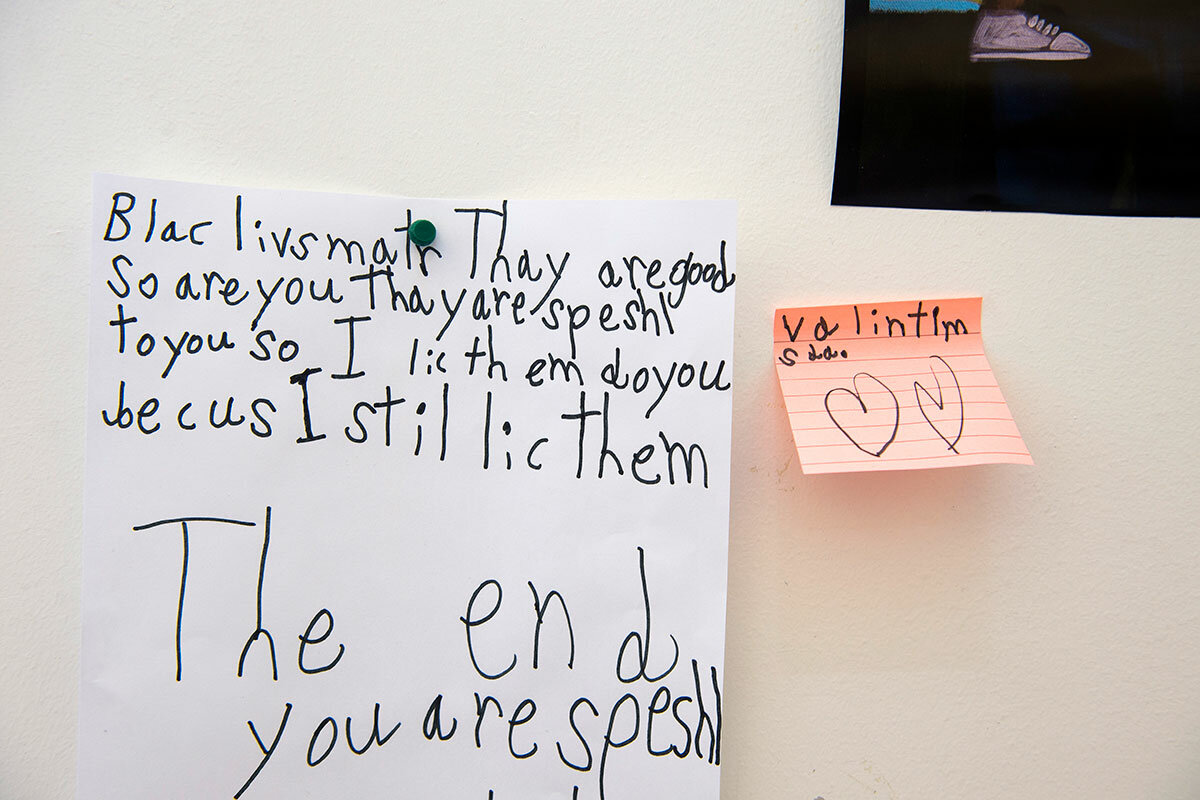

At City Garden Montessori, a charter school not far from a prominent botanical garden here, the students, staff, and even the children’s drawings reflect the racial diversity of the nearby neighborhoods that get preference in the admissions lottery.

The everyday moments hint at the pioneering nature of this place – like the time during a frigid January indoor recess when some children found popsicle sticks and decided to make mini “Black Lives Matter” signs.

Why We Wrote This

At this Missouri school, maintaining racial parity takes vigilance. One outcome is open discussions about race – among students, parents, and staff – that reflect the possibilities of a more integrated society. Part 2 of an occasional series.

Their older elementary peers organized a march last September after the acquittal of a local white police officer who had killed a black man. The school is less than 20 miles from Ferguson, Mo., where the police killing of Michael Brown in 2014 sparked a national movement.

Even before that, a desire for racial equity motivated people at City Garden to rethink how they do education, and to live their commitment in a deep way. The journey to becoming truly integrated has forced them to call upon reserves of hope, moral courage, and perseverance.

City Garden’s mission includes not only racial and economic diversity, but also “anti-bias, antiracist” education, or ABAR, a term used by the Illinois-based Crossroads Antiracism Organizing & Training, which has helped with staff development.

“We no longer have the privilege of pretending that race doesn’t matter,” says Nicole Evans, the school’s African-American principal, who greets students in the morning with hollers and hugs.

“We tell every parent that comes in: This is not just beautiful words on the wall…. This is a matter of life or death for some of our students. Forget about leveling the playing field; this is about being invited to the game,” she says.

Montessori is a child-centered educational approach that started in the tenements of Rome. The United States has an estimated 4,000 Montessori schools, 500 of them public. Among those, about 55 percent are charter schools, according to an analysis by Mira Debs, executive director of the Education Studies Program at Yale University.

“There is a lot the public Montessori sector has accomplished in terms of being a model of diversity over the last 50 years,” but tensions have arisen over “equitable access and the experience of students and teachers of color in those buildings,” Dr. Debs says.

City Garden is one of 125 US charter schools identified as “diverse by design” by The Century Foundation in a first-of-its kind report May 15. Eight Montessori charter schools, and about 2 percent of charters overall, met the criteria.

The small numbers show that school integration hasn't been a priority for the charter sector. That's partly because of “a real absence of leadership in federal law and state charter law to give schools guidance or any kind of incentives to promote diversity,” Debs says. But such grass-roots efforts are important to highlight because they show how charter-school flexibility can be leveraged.

Interest in anti-racism work in Montessori schools is growing. Hundreds of people now attend the annual conference put on in various locations by Montessori for Social Justice, a group that City Garden leaders helped create, and for which Debs has served on the board.

It’s “inviting people into the conversation about what education can be … and how it can contribute to this broader movement for equity and liberation,” says City Garden executive director Christie Huck.

Bringing race to the surface ‘gets messy’

City Garden started in 1995 as a private Montessori preschool. In 2008, black and white parents, including Ms. Huck, helped create the charter school to offer an integrated public Montessori up through grade 8. The city schools had large concentrations of students of color, while the local Catholic schools skewed white.

Last December, it became the first charter in Missouri to gain a 10-year renewal, based on high marks in a quality review. One commitment in its new charter: taking specific steps to try to close racial gaps on state tests.

When Dr. Evans arrived, the school had recently begun anti-bias training among the staff, but it still needed to break out its data by race and take a closer look at “the educational debt” black students were accruing relative to whites, she says.

Evans had also been hearing from parents of color, “We don’t feel like we have a seat at the table.… Our voices are being drowned by white voices.”

Sometimes they meant it literally. She tells of a white father who would come to meetings “and scream and express his disagreement in ways that, quite frankly, if a black man had done it … [some parents said] police would have been called.”

Eventually school officials told that parent he could no longer attend meetings. He and a few other white parents took their children out of the school.

For staff, the journey has involved about 20 hours of anti-bias, or ABAR, training each summer, and professional development sessions during the year. Parents and community members have been welcomed to facilitated “Colorbrave” conversations for several years as well.

“It gets messy sometimes, because this is not easy work or comfortable work,” says Faybra Hemphill, City Garden’s director of racial equity, curriculum, and training.

Ms. Lacey recalls how her first ABAR training prompted “a desperate need to fix everything.” It uncovered her “oblivion,” she says. “I am questioning every decision I make. Every time I raise my voice, every child who gets in trouble, every child who gets praised…. I used to keep tally marks.”

Talking about race openly

Even in a place explicitly countering it, racism still crops up among students.

“Sometimes people, they don’t try to be racist, but sometimes they are,” says McKenzie, a fourth-grader who’s nibbling on pizza during lunch with Black Girls Rock, a group that meets once a month for a field trip or a discussion in the school’s central “living room,” to counter negative social messages.

“One time [a boy] said, ‘How come black people can have their own lunch but white people can’t have theirs?’ ” McKenzie says. “We tried to say that the whole world revolves around white people. And then he goes, like, ‘Well, yeah, because we owned them.’ ”

Although the comment was upsetting, McKenzie says, “I just walked away.”

Before the pizza, Evans read them a picture book celebrating the wide range of skin tones among African-Americans. A beam of sunlight cut through the circle, hitting a patch of sequins on a girl’s shirt and sending sparkles across her friends.

Evans passed a mirror around, asking each one to look in it and declare: “I’m a beautiful black girl.” Some did it hastily while others added in descriptors like “awesome.”

City Garden students say they do make friends across racial lines. “If there’s a thing that goes on with racial tensions [in the news] we’ll talk about it…. [The guides] handle it pretty well,” says Omar, a seventh-grader.

One teachable moment came up early in the school year. Some black students in a fourth- to sixth-grade class had gotten excited about creating a business to make play slime over the summer. They thought of it proudly as a black-owned business. Their enthusiasm spread quickly, though, and in the fall some white students wanted to be part of it.

Ms. Hemphill stopped by to help them talk it through, and “they had this very mature debate,” Evans says.

Some white students helped other white students understand they were overstepping, because the black students had expressed a desire to keep it black-run. (Earlier, students had already had some discussions about the need for whites to work in solidarity with people of color when they see injustice, but at the same time avoid taking over how a response should be organized, Evans says.)

Now, confronted with this business activity their peers were doing after school, a student suggested a solution: The business leaders could call upon other students as “consultants” when they wanted help.

“That was a courageous conversation about race,” Evans says.

Kim Dixon, a white mother, was impressed with her daughter's takeaways. “There are 30-, 40-year-old people that still don’t get that concept … that oppressed people need their own space,” Ms. Dixon says.

Students can handle the conversations, says guide Jori Martinez-Woods. “If we continue with this belief that children are too young to grapple with these ideas, then what we’re saying is, ‘We want to perpetuate this for another generation.’ ”

African-American mom Roni Rodgers is happy the school helps her children manage the dynamics of diverse settings. Parents of a City Garden graduate told her that when a racial issue came up in high school, people were “in awe of how that particular child handled that situation and was not in a fret,” because at City Garden they had seen “what love is, and … how to treat others as you want to be treated.”

Outcomes of successful integration

Nearby the school, old brick houses, some boarded up, sit adjacent to pricey contemporary homes. The neighborhood has been gentrifying, partly because of the school’s success.

For integrated charter schools, it’s a constant challenge to maintain diversity as word gets out and more affluent parents apply, says Debs, from Yale.

City Garden has been able to maintain a racial mix, with about 50 percent white students, but its low-income population, once more than half the school, has shrunk to 39 percent.

In response, the school formed an affordable housing task force, and it has lobbied the state legislature in the hopes that it will allow a weighted lottery to maintain a balance of low-income students.

Mr. Nelson, a teacher with decades of experience in regular public schools, took Montessori training over the summer and started at City Garden in September. He says he was pleasantly surprised by the school’s devotion to anti-bias, antiracist work.

Still, he says, “I’m waiting for the day that we don’t have to have ABAR training…. I’m hoping that these kids will take it there.”

Part 1: Desegregation stalls, but voluntary efforts to boost it show promise