Loading...

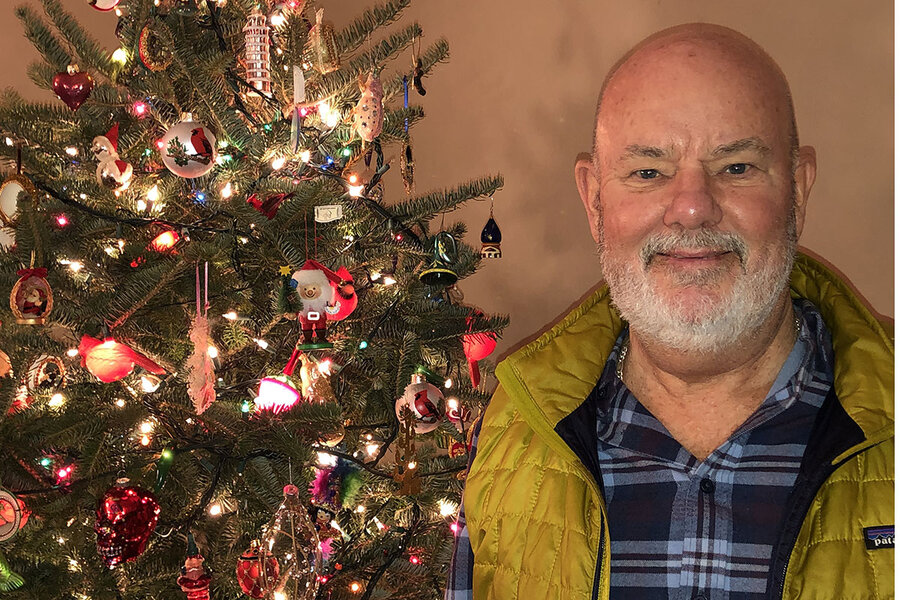

‘This music was a gift’: Howard LaFranchi on how welcomed refugees gave thanks

This Monitor reporter went to Argentina for an economic story. What he found on the streets of Buenos Aires: an expression of gratitude from some of its newest residents for having found home.

The Monitor’s Howard LaFranchi didn’t go to Argentina to write about the Latin Vox Machine. But like any good journalist, he kept his eyes and ears open to what was going on around him.

What he found was a story about a unique form of gratitude – notes of thanksgiving – wafting through the subways of Buenos Aires. He was initially drawn to a quartet of Venezuelan refugees, all classically trained musicians. There were dozens more of these musicians who had come together to form an orchestra that was getting gigs in more traditional venues around the city.

These refugee musicians said they were motivated to give back to their host community by playing in the subways. What surprised Howard was the genuine receptivity and appreciation of this musical gift among the people of Argentina.

This quality of gratitude is one that Howard has seen not just in Argentina, but in other countries where refugees fleeing war or economic crisis seek to use their talents to tangibly say “thank you” to their host countries. Hear about his experiences in this audio piece.

Episode transcript

Ashley Lisenby: Welcome to “Rethinking the News” by The Christian Science Monitor. I’m Ashley Lisenby, one of its producers. Each holiday season, editors and writers discuss some of the most meaningful stories of the year. This year, staff will discuss stories that exemplify five main themes: faith, gratitude, love, hope, and joy. Today’s theme is gratitude.

Listen as Audience Engagement Editor Dave Scott and writer Howard LaFranchi discuss how Venezuelan refugee musicians in Buenos Aires, Argentina, gave back to their new home through the gift of music.

[INTRO MUSIC]

Dave Scott: In 2019, you went to Buenos Aires, Argentina, and you wrote about some of the many Venezuelan refugees who now live there. And you focused on the Venezuelan musicians who play on the streets and in the subways of the city. How did you find this story?

Howard LaFranchi: Well, yeah, so when I went to Argentina, the story was not on my list. But as I was moving around the city in the subway, I was running into musicians playing at a number of the subway stations. And I ended up speaking with one of the musicians and found out that he was from Venezuela. And through speaking to more as I came upon them, found out that there was quite a number of Venezuelan musicians, and they were performing in the in Buenos Aires subway. And I had reported already on the refugee crisis of Venezuelans who have had to leave their country because of the economic crisis there. So speaking with this – with these musicians, I started thinking that maybe there was a story there. So I ended up spending a day with musicians at Metro stops. And it was through that day that I found out about Latin Vox Machine, which is an orchestra that mostly Venezuelan musicians have started up in Buenos Aires.

Scott: And during the holidays, people tend to focus on the value of giving. So this Monitor story kind of highlights gratitude in a somewhat unconventional way. So going in, did you think this would be a story about gratitude?

LaFranchi: No, really not at all. I really saw it as kind of a, you know, an economic story and refugees around the world. But as I – especially that day that I spent in the subway with these musicians, I really saw the kind of the two-way street of gratitude. People went aside as they would stop and listen to these – these musicians, I spoke with a few of them. And so many of them said that they felt that this music was a gift coming to them.

I remember in particular, one woman who said that she got to the point where she – as she came home from her workday on the subway – that she hoped that the musicians would be at her home subway stop. That they brought something really uplifting to the end of her day. And I had spoken with the number of the Venezuelan musicians about their sense of wanting to give back to you know, the country that had taken them in. But it was really when I started talking to the Argentines and their sense of, of the gifts that these refugees were bringing them and how grateful they were for that, that really got me thinking that in an unusual way this was a story about gratitude.

Scott: Hmm, I loved the quote in the story you have from Omar Zambrano, who’s the executive director of the Latin Vox Machine. He tells you that, “People here in Argentina have demonstrated so many of humanity’s values toward us, like welcome and solidarity. And in return, we are giving back our music and our talents as a way of showing our gratitude.” So why might Buenos Aires be an especially appreciative place for these high-caliber musicians and their unique expression of gratitude?

LaFranchi: Yeah, I think there are a number of factors going on. First of all, Buenos Aires is known as – it was long known as the Paris of South America. It’s a very culturally rich city. It has one of the world’s great opera houses. A vibrant theatre scene. And so what that turned out, individually the Venezuelan musicians didn’t organize together to go there. But one by one, they were attracted to that, what they knew to be kind of an appreciation of the arts in Buenos Aires. I think something else that really struck me was that when I did this story, Argentina was going through a very deep, severe recession. Unemployment was high. Newspapers full of articles about falling salaries, people not being able to feed their families or keep their kids in schools. But yet, even in that atmosphere, these refugee musicians were able to make a living, because they had come to a city that really placed a premium and a value on the arts and on music.

Scott: So Howard, this issue of displacement and resettlement. It’s not unique to Venezuela. We’ve seen refugees from the Middle East, Latin America, and Africa flee to more stable governments and economies. I mean, I wrote about a guy named Tareq Hadhad, a Syrian refugee who arrived in Canada a few years ago. And he marveled when he arrived at the airport, he said no one called him a refugee. They called him a “new Canadian.” And so in response to that he was prompted to wonder how to give back to his new country. His father had been a chocolatier in Syria. And so this guy, Mr. Hadhad, started taking a few homemade chocolates to the farmers market in Nova Scotia. And that ultimately blossomed into a chocolate factory, creating dozens of jobs in his adopted country. And he just recently, just a few weeks ago, officially became a Canadian citizen. But it’s that desire to reciprocate that generous welcome, that prompted Mr. Hadhad to give back. And I know that you have traveled around many places in the world. Have you seen that elsewhere besides Venezuela?

LaFranchi: Well, yes. You know, David, as you are right to point out, we are in the midst of what is called the largest refugee and displacement crisis since World War II. U.N. experts speak of 60 million and more people around the world who are displaced, or refugees, who have been forced to leave their homes. And I know that as I have traveled around the world, I’ve certainly seen examples of really this desire, among refugees not to be a burden. Not to be seen as, as sometimes they can be, as threats to security or a drain on resources, but to be contributing to their new homes and to show their appreciation for their new homes.

And I certainly saw this number of years ago, I was doing a story in India. It was [about] a young Rohingya woman, she was a refugee from Burma (Myanmar). And she had come to India and she was certainly grateful for being received. And the reason I was doing a story was [that] she was the first Rohingya refugee to be earning her college degree in India. But it was also a very difficult time in India for Muslims in general, for Indian Muslims and certainly for immigrant or foreign Muslims in the country as, as this young woman being a Rohingya, she was Muslim. And so she was facing some of those same difficulties that other Muslims in India were experiencing.

But despite that, she really was so grateful for what she was getting in India, this opportunity to complete her education. She made a point of taking time out of her week, which was really focused on studying, but taking some time and she volunteered for a social organization in her very poor neighborhood, by working with children. And so I think like the Venezuelans who were giving of themselves in Argentina, this woman was expressing the same desire, I think, that we see so often of refugees who are enriching their homes, in all kinds of ways.

Scott: Research often shows that most of the common misperceptions about immigrants or refugees are just wrong. Study after study shows immigrants are more entrepreneurial than native residents, they rely less on government assistance than native-born residents. And there’s less violent crime in communities with large immigrant groups, even among those that are unauthorized immigrant populations. So I think it’s probably worth remembering, especially in the U.S., as more Afghan refugees are now arriving here, that what you’ve seen in Latin America, especially in Argentina, that there’s a genuine recognition of what refugees can bring to enrich a nation. You’ve been talking about how that Rohingya woman enriched India. And on the other side, you’ve got a genuine a natural desire on the part of refugees to express gratitude for their new – or even temporary – home by giving back whether that’s music or chocolate or helping children with their schoolwork.

Well, Howard, in this season of gratitude and giving, I’m an avid fan of your work, and I thank you for your reporting and for this conversation.

[TRANSITION MUSIC]

Lisenby: Thanks for listening. If you liked this episode, share it with your friends. Or even better, give them the gift of Monitor journalism. Visit CSMonitor.com/Holiday for our discounted holiday offer.

[END]