- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for June 8, 2017

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Understatement is not a strength of the sports world. These days, discussions about which players and teams are the Greatest Of All Time are so ubiquitous that they have their own hashtag (#GOAT). Legends are made and dashed on the Twitterverse’s mayfly life cycles. Perfection seems only an awesome YouTube video away.

Then you watch the Golden State Warriors, and real greatness snaps into focus. The basketball team is on the verge of an unprecedented achievement in American sports. If they defeat the Cleveland Cavaliers Friday, they will finish the playoffs undefeated, 16-0. If the achievement is impressive, the experience of simply watching them is far more so.

In sports, winning is partly the art of hiding weaknesses. To an astonishing degree, the Warriors have virtually none to hide. They are a symphony of movement on offense, a plague of locusts on defense. We gawk at eclipses and comets because they are rare and beautiful things. On occasion, sports, too, can seem celestial.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Comey hearings fallout? Depends on the listener.

Former FBI Director James Comey made an overlooked but insightful statement to Congress Thursday. Beneath all the important investigations into Russian interference in the November elections, there is an unseen side of Washington still united around defending the nation’s core ideals.

Did President Trump’s dealings with then-FBI Director James Comey amount to an obstruction of justice? Democrats tended to view Mr. Comey’s testimony as strengthening the case for that, says Francine Kiefer, who attended Thursday’s hearings on Capitol Hill. Republicans said it pointed to a novice president. But Mr. Comey, in his hearing before the Senate Intelligence Committee, said, “It’s not about Republicans or Democrats.” The big deal, he said, was that Russian government interference in the 2016 election “tried to shape the way we think, we vote, we act…. They’re coming after America, which I hope we all love equally…. And they will be back, because we remain — as difficult as we can be with each other – we remain that shining city on the hill, and they don’t like it.” He praised the bipartisan intelligence committee’s work in working to thwart future Russian meddling. “You are seeing from the outside a lot of acrimony,” acknowledges Sen. Jim Risch (R) of Idaho, “… but inside we are working together to address that issue and how we can keep that from happening again.” Click below for Linda Feldmann’s story on the obstruction question.

Comey hearings fallout? Depends on the listener.

Former FBI director James Comey’s testimony in the Senate, a moment of high anticipation like few in recent Washington history, put questions about unorthodox presidential behavior at center stage.

At its heart, the hearing raised a profound question about President Trump: Was he trying to obstruct justice amid an investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 election and possible collaboration between Trump associates and Russian officials, or was he simply unaware of what a president should or should not do?

“It’s all about trying to figure out what’s going on in someone’s mind,” says Julie O’Sullivan, a former federal prosecutor and law professor at Georgetown University.

In Mr. Comey’s telling, President Trump said he hoped Comey would “let go” an investigation into former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn and his dealings with Russian officials.

“I took it as a very disturbing thing, very concerning,” Comey said Thursday in testimony before the Senate Intelligence Committee. “But that’s a conclusion I'm sure the special counsel will work toward to try and understand what the intention was there and whether that’s an offense.”

Comey also asserted that Trump had asked him for a pledge of “loyalty” in a private dinner one week after the inauguration. That was a highly unusual request for a president to make of an FBI director, who is meant to function as an independent actor. Comey said he acceded to a pledge of “honest loyalty,” clearly uncomfortable with the phrase but not wanting to belabor the point.

Trump’s lawyer denied the request for loyalty

News was made: Comey revealed that it was he who leaked key content of his memos – contemporaneous notes about interactions with Trump both before and after he became president – to a New York Times reporter via a friend who teaches law at Columbia University.

And in the quote of the day, he expressed hope that Trump had indeed taped their Oval Office conversation about Mr. Flynn, suggesting it would bear out Comey’s version.

“Lordy, I hope there are tapes,” Comey said.

Republicans spun Comey’s testimony differently, saying it showed Trump as someone new to government and unsure of appropriate behavior for a president of the United States.

When Trump discussed the Flynn investigation with Comey in the Oval Office on Feb. 14, a day after Flynn’s firing, the president had first asked the others in the room to leave, according to Comey – including Attorney General Jeff Sessions. That created an awkward dynamic that, to some legal observers, suggested an effort by Trump to obstruct justice.

But to House Speaker Paul Ryan, Trump’s handling of the meeting showed that he wasn’t steeped in the protocols of how a president interacts with law enforcement.

“The president’s new at this,” Speaker Ryan told reporters Thursday. “He’s new at government.”

The weight of history hung heavy in the Senate committee room. Two presidents in recent decades, Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton, faced impeachment proceedings that centered in part on obstruction of justice.

In the eyes of some members of Congress and legal observers, Trump’s behavior did rise to the level of obstruction of justice. But Comey did not offer such a conclusion, and was not expected to. His job as head of the FBI was simply to find facts, not formulate charges. As a witness to Trump’s behavior, he took the same approach.

But in saying that the new special counsel, Robert Mueller, would address that question in his investigation of Russian meddling in the 2016 US election, Comey laid down a road map for how one could conclude that Trump had obstructed justice. Comey said he was “stunned” by Trump’s request regarding Flynn, and that top FBI officials found that point to be of “investigative interest.”

“Why did he kick everybody out of the Oval Office?” Comey said. “That, to me as an investigator, is a very significant fact.”

'A consciousness of guilt'

That Trump is an outside-the-box president is beyond dispute. His unorthodox behavior – from unfiltered tweets, to “politically incorrect” assertions, to a rejection of presidential norms – stems from a free-wheeling career in business and entertainment, and no background in politics or public service.

In the modern era, most presidents have sought to expand the bounds of presidential power through executive action. But there’s a difference between aggressive moves to enact policy and possibly crossing legal lines to achieve other goals.

“I would draw a distinction between the kinds of things that presidents do in pushing the bounds of their constitutional powers toward a policy end and pushing the envelope of presidential power in the realm of a criminal investigation,” says Barbara Perry, director of presidential studies at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center.

Legal experts cite as an example Trump’s decision on Feb. 14 to ask others, including Mr. Sessions, to leave the Oval Office so he could discuss the Flynn investigation one-on-one with Comey, as recounted by Comey. Trump’s statement that he hoped Comey would “let this go,” according to Comey, in and of itself doesn’t prove that Trump knew he may have been crossing a line – particularly given suggestions that Trump may not have known better. But other factors may be troubling.

“To some extent, I could buy that, because he isn’t a politician of the sort we usually have,” says Ms. O’Sullivan of Georgetown University. “But he asked [Vice President] Pence and Sessions, [Comey’s] boss, to leave the room. That indicates a consciousness of guilt – that he was about to do something that he didn’t want other people to know about.”

Jens Ohlin, a law professor at Cornell University, agrees that Trump’s Oval Office comment to Comey about Flynn is not, on its own, necessarily proof of obstruction of justice.

“But that, combined with the decision to fire Comey, starts to look like obstruction of justice,” says Dr. Ohlin. “Trump asking him to stop the investigation, then Trump firing him, then Trump admitting in a TV interview that he fired him because of the Russia investigation – all of that together is, I think, very significant.”

The legal definition of “obstruction of justice” entails not just the action itself, but a corrupt intent to engage in influencing, obstructing, or impeding justice.

For Trump, however, the danger would not come in a courtroom, but in Congress, in the event of an impeachment attempt. Impeachment is a political act, but is informed by the law.

The House of Representatives is not close to launching an impeachment effort, especially with a Republican majority. But at the very least, the Comey hearing represents the latest distraction for a White House eager to focus on its policy agenda.

Share this article

Link copied.

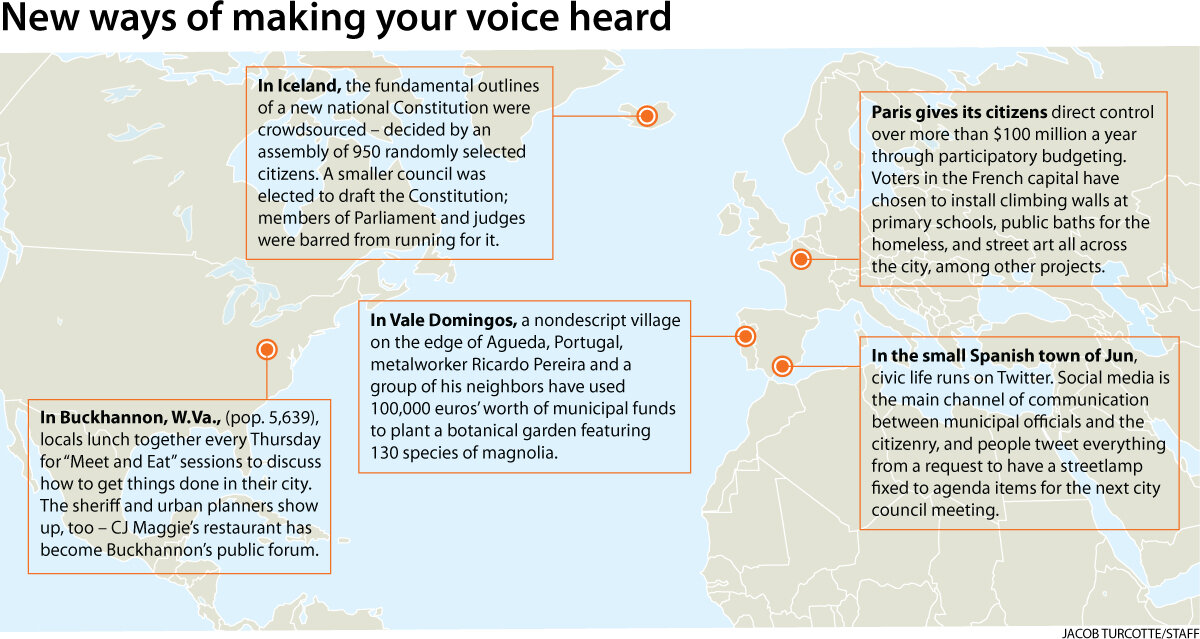

Behind a global rise in ‘direct democracy’

It's easy to throw stones at politicians, metaphorically speaking. But what if citizens made the decisions instead? New experiments in direct democracy in Europe and the United States are forcing voters to be accountable to ... themselves.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Around the world, there are signs that citizens are losing faith in the traditional institutions of representative democracy. Voter turnout is dropping; political party membership has slumped; many voters say they are disenchanted about being ignored by an elitist political class. That has provided an opening for participatory democracy. From Portugal to Iceland and from New York to West Virginia, activists are launching experiments to involve people more actively in political life and to give them a real say in some of the decisions that affect their lives. A key piece: participatory budgeting, through which citizens make binding decisions on how to use public funds. When it works, boosters say, it can be a remedy for many ills, from corruption to political extremism. “What is emerging now,” says a proponent of small-scale direct democracy experiments in Scotland, “is a new, 21st-century idea of representation.”

Behind a global rise in ‘direct democracy’

One recent evening, as rain poured down outside, Ana Paula Lima chose a seat at one of the six tables spread out around her local village hall, its walls decorated with blue and white ceramic tiles. Slowly, others trickled in. At 9:45 p.m., when Mass at the nearby church was over, the meeting began.

Ms. Lima, a 30-something high school teacher, had come to present her idea for a riverside park to other residents of this suburb of Águeda, an industrial town in northern Portugal, and to win their support to get it funded by the city government. Others at the assembly had competing pet projects to promote.

Welcome to participatory democracy, Portuguese style, which gives citizens a chance to come up with their own ideas of how to make their lives better, campaign for community backing for those ideas, and see them made real with public money.

“We have the feeling that politics is corrupt, and it’s difficult to get involved,” Lima said as a handful of townspeople joined her at her table to discuss the three projects that were up for a vote. “This is a way to do things differently.”

Around the world, citizens are losing faith in the traditional institutions of representative democracy. Voter turnout is dropping; political party membership has slumped; a growing number of voters say they are disenchanted about being ignored by an elitist, unresponsive political class.

But at the same time, in many parts of the world, innovative activists are launching imaginative experiments to involve people more actively in political life. And while focused primarily at the local level because of added complications on a larger scale, such efforts give people a real say in some of the decisions that affect their lives.

Relying on citizens to decide issues is not new; juries do that routinely in court. But new forms of direct democracy “give people more voice and more options over questions that are close to them,” says Tanja Aitamurto, a member of the Crowdsourced Democracy Team at Stanford University in California.

That’s a better fit with today’s society, say advocates of new decisionmaking processes. “In the 21st century, citizens are more educated, have the internet, and are not afraid of authority,” says Matt Leighninger, who works for the New York-based nonprofit Public Agenda. “They want to be heard and to contribute.”

All about trust

The idea behind these democratic experiments is that people will have greater trust in decisions they, or their neighbors, have made themselves. And when politicians implement those decisions, some of that confidence will rub off on them.

They could use that trust. In the United States, just 10 percent of Americans have a great deal of confidence in the country’s overall political system, while 51 percent have only some confidence and 38 percent have hardly any confidence, according to a poll last year by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

And it’s not just an American problem. Milan Ranđelović, the head of economic development in Serbia’s third-largest city, Nis, knows what it looks like, too.

“The city government has a telephone help line, an SMS service, and an app for citizens to report problems in their neighborhoods,” he says. “They don’t use them; they call in to local radio shows instead. People have lost faith in the system.”

It’s a common phenomenon. In 21 of the 28 countries surveyed by the Edelman Trust Barometer last year, citizens who trusted their government were in the minority. In 19 countries, a majority believe that their political and social systems are failing.

And that translates into apathy. Around the world, voter turnout at elections has been sliding for the past 30 years, studies by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance in Stockholm show. It has gotten so bad in Europe, a recent International IDEA report warned, that “there is a risk that elections might lose their appeal ... as a fundamental tool of democratic governance.”

The most popular idea

Of all the new and alternative tools that have sprung up in recent years, none have spread as widely across the globe as participatory budgeting, the process in which citizens make binding decisions on how to spend public funds.

Boosters see it as a remedy for many ills, from corruption to political extremism. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t.

In Valongo do Vouga the other evening, Lima had a chance to put forward her project for a riverside recreation area. Eventually it won enough votes to go forward to a feasibility study by city engineers. But the meeting was hardly an example of vibrant democratic debate animated by a sense of civic responsibility.

What happened was that a former mayor of the district, Antonio Rachinhas, had rallied relatives and neighbors to show up and vote en masse for his proposal to spruce up a public park near his home. They spread themselves out among the six discussion tables and dominated the proceedings.

Almost all Mr. Rachinhas’s supporters gave both their votes to his project. Lima’s idea and someone else’s proposal (to fill in a half-built, abandoned swimming pool and grass it over into a sports facility) went through only because the meeting was empowered to approve three projects.

“You often find that these meetings have been decided in advance,” says Cesar Silva, an information technology entrepreneur who sold the software that the Águeda City Council uses to manage its participatory budget program. “It’s politics.”

That frustrated Daniela Hercolano, the current mayor’s chief of staff and a champion of participatory budgeting who moderated the meeting. “Old pols who know their way around used this space to push their agenda,” she complains. “But that is not usual.”

Participatory budgeting has worked well in the three years since Águeda embraced it, she says, and it has drawn in just the sort of citizens who are disillusioned with the “old pols.” Sixty percent of participants do not normally vote in national or regional elections, according to Ms. Hercolano.

“It has changed two things in the city,” she says. “The administration is closer now to citizens, and to problems it had not been aware of; and it has strengthened the community. It makes Águeda easier to govern, but it means political leaders have to be ready to share management with citizens,” she adds.

Projects around the globe

In the industrialized world, some governments are turning to participatory democracy channels to help set broad policy: The Finnish government invited ideas on how best to regulate off-road vehicles, and in Palo Alto, Calif., the city leaders crowdsourced ways to update their urban planning strategy.

For the most part, though, participatory budget projects in the developed world are small fry, of consequence only to the people living in the neighborhood. In Maribor, for example, a crumbling postindustrial city in Slovenia, participatory democracy activists were motivated by a desire to rebuild a sense of community, but the changes that emerged from the public debates they organized included such mundane things as more trash cans and gardening classes for schoolchildren.

Parisians were particularly keen on having more public toilets and cleaner streets. In Cowdenbeath, Scotland, townspeople chose to extend the network of bicycle paths and build an outdoor gym.

In general, participatory budgeting seems to have worked best when it has funded projects close to people’s homes and hearts, although Portugal is trying a national version this year.

In the developing world, participatory budgeting has had a much stronger effect, says Tiago Peixoto, senior governance specialist at the World Bank and a leading “new democracy” guru. In fact, it saves lives. [Editor's note: This paragraph was updated to clarify Mr. Peixoto's title.]

In Brazilian cities that had been using participatory budgeting for more than eight years, infant mortality rates were 20 percent lower than the national mean, two US researchers found in a 2014 study. That, says Dr. Peixoto, is because “local people know better than governments what they need” and use the money they control to improve sanitation, access to water, and other services that better their health.

In India, citizens’ audits have reduced corruption. Studies in Russia, Latin America, and Europe have found that people cheat on their taxes less in cities where participatory budgeting has given them the sense that their preferences have been taken into account.

“You see positive effects across the spectrum, on citizens’ social capital, on solidarity, on resilience,” says Peixoto. “There are more good development outcomes.”

Reality check

Even participatory democracy’s most enthusiastic advocates do not pretend that its processes always faithfully represent public opinion or that they draw on representative samples. Those who choose to join are a self-selected group.

When participation rates are low, that casts doubt on the legitimacy of the results. If 10 to 15 percent of a local population votes on projects emerging from a participatory budget, that is considered good by most experts in the field.

Technology can help people take part, offering the chance to vote by SMS or on a website, or providing the opportunity to form online discussion groups to refine ideas and lobby for them. A mix of high technology and simple face-to-face meetings tends to elicit the best response, say people whose job it is to design participatory democracy processes.

Even so, cautions Mr. Silva, who designs software to make participation easier in Portugal, “when you haven’t listened to citizens for a hundred years, you cannot expect them to engage massively overnight.”

Equally problematic in many parts of the world is the resistance that local politicians and bureaucrats may put up to the idea of more popular participation in decisionmaking. The ideas that the citizens of Maribor came up with were hardly revolutionary, but the city government dragged its feet at every opportunity, complains Gregor Stamejcic, one of the activists who helped introduce participatory budgeting in his city.

“The municipality does not want to give up its power,” he explains. “They find it a challenge to their authority and don’t see that it could make their job easier.”

Support from the authorities is a key condition for success, says Peixoto. “If politicians feel threatened by this, the process is short-lived,” he warns.

Indeed, a lack of support from the local government can ruin even the strongest experiments.

Earlier this year Porto Alegre, Brazil, which in 1989 became the first city in the world to introduce participatory budgeting and is the global poster child for the whole idea, suspended its program for two years. A backlog of projects that citizens chose but the city could not find the money to pay for was undermining the program’s credibility.

Despite the problems, participatory budgeting is spreading worldwide, and other forms of more direct democracy are going mainstream. Traditional representative democracy may be creaky and showing signs of age, but it is old-fashioned anyway, says Alistair Stoddart, who works for The Democratic Society in Scotland, setting up small-scale direct democracy experiments.

“What is emerging now,” he says, “is a new, 21st-century idea of representation.”

Protected by executive order, but still facing deportation

The law is intended to provide clarity and certainty. But executive actions in recent years have made a muddle for some young unauthorized immigrants. They don't know if they're welcome in the United States or not. As the courts decide, they wait and wonder.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Patrik Jonsson Staff writer

Can federal judges rule on how legally binding are the promises the federal government made to young people who were brought to the United States as young children? That question is at the heart of a due-process case that was heard Thursday in Atlanta, regarding the status of a young woman whose temporary legal status was summarily revoked by immigration agents. The government’s lawyers argued that the US District Court doesn’t have jurisdiction over this kind of immigration case. Attorneys for Jessica Colotl, who came to the US as an 8-year-old and was granted deferred action status, said the government needed to follow its own guidelines and procedures. “This is a case where the government basically says, ‘We can make the rules, we can break the rules, and there's nothing you can do about it,’ ” says Charles Kuck, Ms. Colotl’s immigration lawyer. “That should make every citizen concerned.”

Protected by executive order, but still facing deportation

After a two-hour hearing in Courtroom 1905 at the Richard B. Russell Federal Building and United States Courthouse in Atlanta, Jessica Colotl found herself mobbed by friends.

Ms. Colotl, who nearly a decade ago became the face of attempts in Georgia to ban undocumented immigrants from state colleges, once again has landed in the middle of a high-stakes immigration debate. This time, it's about whether the US government can arbitrarily decide when to withdraw temporary status gained under a deferred action program.

President Trump has promised the roughly 800,000 DREAMers, who were brought to the US as children, that his administration will treat them the same as the Obama administration did. And Mr. Trump has left in place the executive order governing their treatment – including giving them work permits and granting them temporary protection from deportation. But in May, Ms. Colotl was stunned to hear that her Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) status had been revoked, allegedly for a felony tied to a 2011 traffic incident.

In court on Thursday, however, the government’s lawyers acknowledged that there was no felony conviction, causing US District Judge Mark Cohen to wonder whether immigration officials were acting arbitrarily against a DREAMer. Judge Cohen said he would decide the case over the weekend.

“My main hope is to be able to go back to my regular life,” Colotl, a paralegal who has not been able to work or drive since May 3, told the Monitor after the hearing. “But I’m also hoping this will set the stage for other DREAMers, to where the government can’t arbitrarily revoke work permits or do other nonsense things” to DREAMers.

The government’s lawyers argued that the US District Court doesn’t have jurisdiction over this kind of immigration case. They said it was “unlikely” that Colotl would be detained as she awaited the resolution of her separate immigration case.

In essence a due process case, Colotl’s lawyers say it’s also about a fundamental promise made by the US government to these young people. Her attorneys argue that the government needed to follow its own guidelines and procedures, which they say would allow Colotl to get an extension to her work permit and driving privileges, which in Georgia are linked.

“This is a case where the government basically says, ‘We can make the rules, we can break the rules and there’s nothing you can do about it,’ ” says Charles Kuck, Colotl’s immigration lawyer. “That should make every citizen concerned.”

The Department of Homeland Security disagrees, however, and asserts that, indeed, it has virtually unlimited discretionary power to deport anyone here illegally.

“An individual with deferred action remains removable at any time, and DHS has the discretion to revoke deferred action unilaterally,” department attorneys argued in court documents on Thursday. They also pointed out the US Citizenship and Immigration Services informs the public that “DACA is an exercise of prosecutorial discretion and deferred action may be terminated at any time.”

Agencies' rules

As the Trump administration continues to aggressively enforce the nation’s immigration laws, in some cases deporting long-time residents without criminal records, a growing number of critics contend that the Trump administration has used its wide discretionary authority in an arbitrary and perhaps unconstitutional way.

Last week, a coalition of more than 200 advocacy groups, legal representatives, and faith leaders announced that they had begun to document a rise in what they say is the administration’s “arbitrary and capricious denials of bond and parole,” especially for asylum seekers.

“ICE routinely elects to deny parole for even the most urgent, humanitarian, and exceedingly reasonable requests,” they wrote in a letter to the agency’s director.

Like Colotl’s attorneys, they question whether the Trump administration may have violated federal administrative laws that require all federal agencies to obey their own rules. And they, too, see possible due process violations.

“In terms of what we’re documenting, many people who were denied parole or refused bonds were just given a cursory review of their case,” says Christina Fialho, executive director of Community Initiatives for Visiting Immigrants in Confinement, which organized the coalition. “Many received no explanation for the reasons why they were denied, even after their attorneys tried to obtain information from ICE agents.”

Delayed hearings

After six weeks of being locked up in an immigration detention center in Milan, N.M., Fredi Carrillo Martinez was starting to feel a little desperate.

An undocumented immigrant who has a DACA application pending, Mr. Carrillo Martinez, who was brought by his father to the United States when he was 8, had been picked up at an immigration checkpoint in early April. Prior to this, he had not been in trouble with the law before in 26 years in the country.

By mid-May, the rent for his apartment in Beaumont, Texas, was due, and his US-born wife and two sons were living on the family’s $4,000 in savings – which they had hoped to eventually use to buy a house, he says. He had expected to see a judge and post bond within 10 days, but officials told him his case had been delayed.

“The one thing that hurt the most, though, was that I had to have a conversation with my son, why I couldn’t make it to his award ceremony for the honor society at school,” says Carrillo Martinez, who had been working as a satellite dish technician.

With the help of a Santa Fe Dreamers Project attorney, Carrillo Martinez was able to go before an immigration judge, who issued him a $2,000 bond as he waits for his next hearing. His case does not appear as clear-cut as Colotl’s. “In reality, it’s disconcerting that there is a real possibility that I may be deported,” he says.

Nearly 61 percent of immigrants issued a “notice to appear” summons are now being held in detention, compared with about 27 percent of those issued notices to appear under the Obama administration.

The Trump administration, too, has put an end to the Obama administration’s “catch and release” policy, in which only those convicted of a serious felony or who posed a risk to public safety or national security were kept locked up. Supporters applaud the stronger stance against illegal immigration. But more families are being broken apart as immigrants with no criminal record are kept in detention, advocates say.

But as long as the administration adheres to the letter of the law, courts have not intervened.

Last month, the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit denied a request by an undocumented named Andres Magana Ortiz, who had been a respected member of Hawaii’s coffee farming industry for nearly three decades.

Mr. Magana Ortiz, who is married to a US citizen and has three US-born children, entered the country illegally when he was 15, and has lived in the US for the past 28 years.

According to the 9th Circuit panel, the long-time coffee farmer was “by all accounts a pillar of his community,” even allowing the US Department of Agriculture to conduct a five-year study on his land for free. But the court, considered one of the more liberal federal circuits, agreed that it was well within the Trump administration’s discretionary powers to deport him and bar him from returning for 10 years.

No blanket protection?

The question becomes what happens when government actions are contrary to its stated rules.

In April, Attorney General Jeff Sessions made clear that even though DACA participants were not necessarily being targeted for deportation, they should not assume they had blanket protection. “Everybody in the country illegally is subject to being deported, so people come here and they stay here a few years and somehow they think they are not subject to being deported – well, they are,” he said.

But critics say, as long as the Trump administration continues to leave Obama’s DACA executive actions in place, they have to abide by its guidelines.

“It’s of course true that the administration could get rid of the DACA program, but the important fact here is that they haven’t, and nothing has changed about the program’s rules,” says Michael Tan, staff attorney for the ACLU’s Immigrants’ Rights Project, in a conference call with reporters on Wednesday.

“It’s a principle of black letter law that agencies have to follow their own policies. So as long as DACA is in place, and those rules have remained unchanged, the government has no business going out there and saying, Jessica is somehow ineligible for DACA,” he continued.

Colotl says the Trump administration’s actions have sent a chill through many DACA beneficiaries. “All of them are feeling scared right now,” she says, “and they’re worried this could be taken away at any moment.”

In new Irish leader, more evidence of long social shift

The naming of a prime minister is often routine politics. But we saw something of significance happening in Ireland, where the identity of the next leader is making a statement about the country itself: This is not the Ireland of so many stereotypes.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Bertie Ahern, Brian Cowen, Enda Kenny, Leo Varadkar. If asked which of these four men is the current leader of Ireland’s ruling party, most people would likely dismiss the last, with his Indian surname, out of hand. But Mr. Varadkar is indeed set to be named “taoiseach,” or prime minister, later this month. (The other three are his predecessors in the post.) And it is not just his Indian heritage that defies stereotypes about the Irish: He is also openly gay. And his rise to power is a clear indicator that the Ireland many may have in mind is long gone, replaced by a far more cosmopolitan society. Once an emigrant nation, Ireland became a destination for inward migration during the so-called Celtic Tiger years around the turn of the century. The Catholic Church, once the arbiter of Irish society, lost its moral authority after child abuse scandals and the mistreatment handed out in the Magdalene Laundries. And no anti-immigration political party has ever succeeded at the polls, and no mainstream party favors “making Ireland great again.”

In new Irish leader, more evidence of long social shift

Rarely does the appointment of a new Irish prime minister make global headlines. But Leo Varadkar, who won his party’s leadership campaign last week, has been hailed by the world’s press as symbolizing a changed Ireland.

Openly gay and the son of an Indian immigrant doctor, the 39-year-old Mr. Varadkar will be Ireland’s youngest ever prime minister, or "taoiseach," when he assumes the office in the coming days. That he could so easily seize the crown of the center-right and traditionalist Fine Gael party has been taken as a sign that the values that governed Ireland no longer hold the sway they once did.

In truth, they haven’t for decades.

Despite the historical firsts that Varadkar's appointment will bring, Ireland is no longer either a rural idyll that exported little more than cattle on-the-hoof, nor an inward-looking, quasi-self-sufficient republic.

Ireland today has closely resembled every other state in Western Europe for quite some time, driven in large part by the economic and demographic changes brought about by the "Celtic Tiger" boom of the 1990s and 2000s. And though the Roman Catholic Church defined Irish morality for many centuries, its hold has largely been broken by abuse scandals and associated cover-ups going back decades. As a result, while Varadkar's rise seems out of the blue, it is part and parcel of what Ireland is today, stereotypes to the contrary.

A more cosmopolitan nation

Ireland was late to decriminalize homosexuality in 1993, but the pace of change has been breathtaking, with civil partnerships introduced in 2010, followed by the legalization of same sex marriage in a 2015 referendum. It was during the referendum campaign that Varadkar "came out," throwing his support behind the "Yes" side.

Earlier that year, the country also passed a law recognizing gender by self-description alone – the first country in Europe to do so.

These social developments followed two decades of rapid economic change driven by foreign-direct investment, primarily in information technology and pharmaceutical manufacturing, and, in a move that later caused the country’s precipitous fall from grace following the 2008 global economic crisis, the domestic construction industry.

Ireland, long an emigrant nation, also became a destination for inward migration, primarily from eastern and central Europe, but also from Africa, China, and Brazil. Despite the occasional street incident and accusations of silent and invisible discrimination common to most European countries, no anti-immigration political party has ever succeeded at the polls, and no mainstream party favors anti-immigrant policies.

Outward migration again became an issue in the years after 2008, with more than 200,000 of the 4.2 million population leaving in search of work. By 2014 an estimated 10 percent of young people had left, with rural areas particularly hard hit.

For his part, Varadkar has dismissed attempts to view him through the prism of identity politics.

“It’s not something that defines me. I’m not a half-Indian politician or a doctor politician or a gay politician, for that matter. It’s just part of who I am, it doesn’t define me, it is part of my character I suppose,” he told Irish state broadcaster RTÉ.

Most Irish seem to agree: unlike in Britain, Irish politicians’ personal lives are rarely the subject of even tabloid newspaper stories, and Varadkar’s rise has been no different. Varadkar’s sexuality was only an issue to the extent that it was discussed as putting a positive spin on the country in the eyes of the world.

In fact, the Irish left, emboldened since the economic crisis, has been sharply critical of Varadkar, whom it sees as simply the next in a line of made-to-order right-wing prime ministers.

Catholic Church's curbed influence

The transformation of Ireland is nothing new, but it is also not yet over. Like Spain, for example, painful reminders of the past continue to inform the present.

The republic had been rocked since the 1990s by a series of scandals involving the Catholic Church, which was long intertwined with the state in the provision of social services. At precisely the time the country started to become wealthy, the church’s moral authority was sapped by allegations, later proved true, of widespread sexual and physical abuse of minors in church-run care homes. Demands that church and state should be formally separated were bolstered by later revelations of mistreatment of rural and working class single mothers, institutionalized in the so-called "Magdalene laundries."

Although its influence, both morally and practically, has waned, the church still controls the majority of Irish schools and has a presence in healthcare, but a movement is growing to change this. In May it was announced that the Sisters of Charity Catholic order of nuns was withdrawing from its role in a planned new maternity hospital.

Education may be trickier. Although secular as well as Protestant and Gaelic-language schools exist, the majority of state schools continue to be run, at least formally, by the Catholic Church – and the state has shown little interest in buying them out. Catholic Archbishop of Dublin Diarmuid Martin has been among the voices arguing for wider patronage of schools, complaining in 2012 that the state was hampering the church’s efforts to divest control.

Other battles are ongoing, too. One of the toughest Varadkar will face is that of abortion, which has been the third rail of Irish politics for more than three decades.

A vocal movement has grown, calling for the scrapping of Ireland’s constitutional ban on abortion and Varadkar, in true Irish political fashion, has made noises indicating support for both sides. A compromise proposal allowing for abortion in the case of fatal fetal abnormality is likely, but it remains to be seen if such as measure can gain the support of Ireland’s more traditional voters, many of whom are clustered in Varadkar’s Fine Gael party.

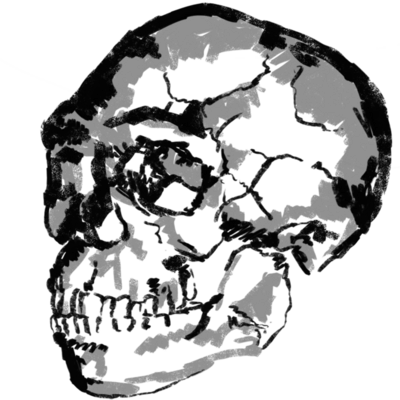

A revealing fossil find sheds light on a science

The rocks of Africa might as well be outer space, in some ways. The discovery in Morocco of the oldest known Homo sapiens fossil shows how much we have discovered about the origins of humans – and how much we haven't.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

When paleoanthropologists reported Wednesday that they had found the oldest Homo sapiens fossils yet, headline writers had a field day declaring that new fossil discoveries could rewrite the history of human evolution. If that idea sounds familiar, it’s because our understanding of evolution is, well, evolving. “We’re sort of incrementally inching in upon a better description of nature,” says Ian Tattersall, a paleoanthropologist with the American Museum of Natural History in New York. He says that “everything has changed completely” since he first stepped into the paleoanthropology field half a century ago, “and it would be very hubristic of me to suppose that things won’t have changed just as much in another 50 years.” Each new fossil is a boon, researchers say, because it sharpens scientists' focus just a bit more. The latest discovery shifts previous estimates of the emergence of modern humans back 100,000 years, to 300,000 years ago, adding another data point to the story of our species.

A revealing fossil find sheds light on a science

Some old bones made big headlines this week, as paleoanthropologists reported that they had identified the oldest Homo sapiens fossils yet.

Freshly dated to be about 300,000 years old, a collection of fossils and stone artifacts unearthed in Morocco could push the origin of our species back 100,000 years, scientists say in two papers published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

Such a dramatic new date in human prehistory may seem shocking, especially to people who expect evolution to follow a tidy linear progression. But it's actually indicative of how this science works – and how understanding of evolution itself has shifted.

Paleoanthropology is kind of like a connect-the-dot puzzle, says Shara Bailey, a coauthor of one of the Nature papers and a paleoanthropologist at New York University. “But you don't have any numbers on it and only a quarter of the dots are there. Will you be able to recreate what that puzzle is? Not necessarily. But as you get more dots and you can put numbers on it, you can get a clearer picture of what that puzzle is actually supposed to be.”

Each new fossil and date is a boon for scientists, she explains, because it adds another dot and number to that sparse picture.

One reason that picture of early humanity is so sparse is that scientists didn't always know where to look for early human fossils, or have the funding or permission to search willy-nilly. Early in the process of piecing together the story of human prehistory, many human-like fossils were found in Europe, so some supposed that Homo sapiens first arose on that continent. But, as Professor Bailey points out, that's just where dense human activity might accidentally uncover fossils, and where a lot of scientists were looking.

Over the decades, as much older fossils have been found in Africa and genetics research has also pointed to an African origin of modern humans, that narrative shifted.

Before this North African site claimed the title of oldest Homo sapiens site, a 195,000-year-old site thousands of miles away in Ethiopia wore that crown. And with other similarly aged Homo sapiens sites nearby, some scientists pointed to East Africa as the birthplace of our species. Now researchers say the Moroccan site, called Jebel Irhoud, adds a new wrinkle.

“We're sort of incrementally inching in upon a better description of nature,” says Ian Tattersall, a paleoanthropologist and curator emeritus with the American Museum of Natural History, who was not involved in the new research.

He says “everything has changed completely” since he first stepped into the paleoanthropology field half a century ago, “and it would be very hubristic of me to suppose that things won't have changed just as much in another 50 years.”

An evolution of ideas sheds new light

The Jebel Irhoud fossils themselves are an example of how paleoanthropology has evolved over the decades.

The prehistoric site was an accidental find in the early 1960s. During mining operations, a section of earth collapsed, revealing various bones – including a nearly complete hominin skull. At the time, six hominin fossils were collected from the site.

Those six fossils left paleoanthropologists scratching their heads. The site was thought to be around 40,000 years old, but the fossils displayed a combination of primitive and modern features that didn’t fit the current thinking about evolutionary timelines.

But with fresh excavations of the site starting in 2004, pieces of the puzzle began to fall into place.

In the decades since the first fossils emerged from the mine, evolutionary models have continued to shift, especially as scientists have developed more advanced dating techniques. These revised dates are older, and make the Jebel Irhoud hominins seem less like oddballs, as they now seem to have a place near the base of the Homo sapiens clade.

Dating has been “a stumbling point for a lot of people,” says Christian Tryon, a paleolithic archaeologist at Harvard University who was not involved in the new research. It's challenging to pin down an exact age of an archaeological site and they often come with uncertainties and wide margins of error, he says.

In this case, two newer dating techniques place the Jebel Irhoud site somewhere between 254,000 and 349,000 years old.

Messy evolution makes for messy paleoanthropology

Another thing that often muddies the waters of paleoanthropology is the old model of evolution as a linear “slog from primitiveness to perfection,” Dr. Tattersall says.

In that view, modern humans evolved out of a long chain of hominins, starting with the primitive primates and becoming increasingly sophisticated and more like us over time. The Jebel Irhoud fossils would probably be considered our direct ancestors, if that was how evolution worked.

But evolution is not linear and instead has many branches. And as such, the fossil record shows that human prehistory was a story of “tremendous evolutionary experimentation with different takes on what a member of the genus Homo could be,” Tattersall says. “And this is a wonderful illustration of that.”

In fact, Dr. Tryon says, “the way evolution works, extinction is the norm.”

With that mindset, the new fossils could be members of a population of early Homo sapiens relatives that ultimately died out. Or perhaps, as authors of the new papers suggest, populations across Africa may have been evolving different characteristics and then interbred later to mix those features to yield what we now see in human skeletons.

Sorting out those evolutionary patterns may be tricky. Africa is a large continent, and the collection of Homo sapiens specimens is “woefully small,” says Bernard Wood, a paleoanthropologist at George Washington University who was not involved in the new research.

And, given the nature of the fossil record and paleoanthropology, Dr. Wood says the implications of the new discoveries are not surprising. “It’s inevitable that the story changes by expanding the geography and increasing the time-depth” of our species’ history, he says.

But, Wood says, with this new research, “we're not as ignorant as we were before it was published.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

France takes a turn neither left nor right

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

Emmanuel Macron, a former banker who once worked under a Socialist president, won the French presidency handily on a promise of political renewal and centrist policies. So far he’s been true to his word. His cabinet ministers reflect a range of views. And most of Mr. Macron’s candidates for France’s legislative elections this month are newcomers. His plans for economic reform face head winds. But much of the country is agog over Macron and his “cross party” vision. The French, says Macron, have chosen “a spirit of achievement over a spirit of division.” The activism that Macron inspired must not give way to the old ways of assuming that elected leaders will make the correct decisions. To really dissolve left and right in politics, the French now must work together.

France takes a turn neither left nor right

The French invented the meaning of left and right in politics. In the 18th century, commoners sat on the king’s left while the aristocracy sat on his right. But after the election of Emmanuel Macron as president in May and his new party’s expected victory in legislative elections this month, France may need to update those labels or dispense with them.

That could help other democracies stuck in polarized politics, especially the United States.

Mr. Macron, a former banker who once worked under a Socialist president, won handily on a promise of political renewal and centrist policies. So far he’s been true to his word. His cabinet ministers reflect a range of views. His choice for prime minister, Édouard Philippe, is on the right but was a popular mayor in the left-leaning city of Le Havre in the Normandy region. And only 5 percent of Macron’s candidates for the coming election are former members of Parliament. Most are newcomers, including a female bullfighter and a renowned mathematician.

France was ripe to rip up the political rule book. Before the election, 85 percent of people said the country was heading in the wrong direction. Neither of the two traditional parties was strong enough to make it to the final round of May’s presidential contest. Macron’s party (En Marche!, or On the Move) was founded only last year. Yet he won with two-thirds of the vote.

Now the French are agog over Macron and his “cross-party” vision. A new poll by INSEE shows the country’s morale is at its highest in 10 years. And Macron has already renamed the party – which he calls a citizens’ movement – to La République En Marche! His ministers have begun to clean up government and push power down to local levels. The French, says Macron, have chosen “a spirit of achievement over a spirit of division.”

His plans for economic reform still face strong head winds, especially from unions. But his main goal is to help the French “believe in themselves,” he says. In an earlier book, “Révolution,” he wrote that authority must not be imposed and that citizens must “remain masters of our own clocks, of our principles, and not abandon them....

“To establish real political authority ... one must reach a consensus in clarity, not twilight compromises.”

For this hope to survive, the local activism that he inspired must not give way to the old ways of assuming that elected leaders will make the correct decisions. To really dissolve left and right in politics, the French must work together in their communities, finding that “consensus in clarity.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Comfort for mourners

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

Contributor Mark Swinney shares how he sought comfort and healing when his father passed on. Step by step he was lifted out of grief as he came to see that the qualities he treasured in his dad would always be with him, because they were a unique reflection of divine Love that is always with us. Even in the midst of grief, we can turn to this Love and feel the light of its presence, assuring us that we are always cherished and loved.

Comfort for mourners

At times of loss, it’s wonderful to have comfort from family and friends. And I have also found that lasting comfort can be spiritual, derived directly from the Divine. An idea that’s helped me again and again is that we are not simply physical beings that stop existing. We are actually spiritually created, the image of God, and so everyone is inseparable from God, divine Love and Life. Nothing can ever change that. We are all created to express the joyful, loving nature of God. And we can keep on enjoying the goodness of those we love even when they’re not with us.

When my father passed, I prayed for comfort. It wasn’t an easy time, but I began to see that my father hadn’t created the wonderful qualities I loved in him; he reflected those qualities from their divine source – just as the moon doesn’t create light on its own, but reflects the sun’s light. In other words, everything I had loved about my dad, I actually would get to keep. The love with which my dad loved me was truly God’s love, which is always with us, reflected in us in wonderful and unique ways. And I saw that I could honor my father’s memory by consciously expressing God’s love, just as I’d seen him do.

Divine Love never lets us go, so we can trust that we are never alone. I particularly love how this idea of God’s ever-presence is symbolized in an instructive story told by Christ Jesus, in which a father says to a son who was feeling left out of his embrace, “Thou art ever with me, and all that I have is thine” (Luke 15:31).

When mourning for those who have passed from our sight, we can pray to feel the touch of God’s love. Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy defined angels as God’s thoughts that we can intuit. She wrote: “Oh, may you feel this touch, – it is not the clasping of hands, nor a loved person present; it is more than this: it is a spiritual idea that lights your path!” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 306).

May we all feel the light of God’s loving nature and presence, the divine message in our hearts assuring us that we and our loved ones are constantly cherished and loved.

A message of love

Standing against bloodshed

A look ahead

Thanks for reading today. Please keep coming back. We’re working on this story from Paris: How Emmanuel Macron, the most improbable of French presidents, could be poised to capture the largest majority in the lower house of any president in the past two decades.