- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for July 3, 2017

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Every Fourth of July, I like to remind myself what an astonishing experiment America is. Certainly, it was an experiment in 1776 when the Founders took an unprecedented step toward giving citizens the right to “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” But it’s still an experiment now.

There is no country on earth that is simultaneously as big, as free, as diverse, as developed. The state historian of California once told me that lawmakers there deal with third-world problems and first-world expectations. Through every generation, the United States has gotten successively bigger, more free, more diverse, more developed. It is a unique, real-time test of how much liberty, equality, and self-government the human race can manage. And how America has managed that test has mattered for the human race. The US president isn’t hailed as the “leader of the free world” just because of the nuclear briefcase.

This Fourth of July, the question seems as poignant as ever: Can America grow yet bigger, even more free, diverse, and prosperous? That history is ours to write.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

For GOP, health-care saga becomes deepening test of credibility

Bold lawmaking can come at a cost. House Democrats still haven't recovered from their 2009 "Obamacare" vote. So it's no wonder congressional Republicans are being a bit cautious. But their lack of action is starting to create a cost of its own.

It might seem like a slam-dunk opportunity. Republicans in Congress have been pledging for years to repeal and replace "Obamacare." They've won elections partly on that promise. And now Republicans control the White House and both houses of Congress. But to Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell and his colleagues, it’s proving anything but easy. That’s partly because their majority in the Senate is slim. It’s also that partial repeal is synonymous with millions of Americans losing health insurance, according to Congressional Budget Office projections. “The longer this plays out, the more you’re going to hear from people who stand to suffer,” says John Pitney, a political scientist at Claremont McKenna College. That helps explain why Senator McConnell has been eager to move the bill quickly. After a failed effort to pass a bill before the Fourth of July, the issue has become a major test of the party’s credibility. If they can’t do this, can they do tax reform, or other major legislation? The party, it seems, needs to relearn what it means to govern.

For GOP, health-care saga becomes deepening test of credibility

When Republicans swept last November’s elections, the sky appeared to be the limit. Obamacare would be repealed and replaced. The tax system would be overhauled. American infrastructure would at last get a major infusion of cash.

All of this may yet happen, but promises of speedy change haven’t materialized. Health-care reform is stalled in the Senate, and the details of tax reform are still on the drawing board. Then there’s President Trump, who has complicated efforts to revive health reform by suggesting “repeal first, replace later” – a stark turnabout from his pledge to do both at once.

And in eye-popping fashion, Mr. Trump has sucked the oxygen away from policy altogether since last Thursday with sensational tweets attacking the media personalities and outlets – most recently a video of Trump body-slamming a “CNN” avatar.

But it’s congressional Republicans whose credibility is on the line, foremost. After eight years of Barack Obama, and years of symbolic votes to undo the Affordable Care Act (ACA), they now have an ally in the White House – one who is eager to sign major legislation.

Since Trump won the presidency, “the Republican Party, particularly in Congress, has not understood that their job is to govern,” says GOP strategist Ford O’Connell. “And when you govern, sometimes you have to man up and walk the plank.”

That means voting for legislation you don’t love, and that may even cost some members reelection. And for both leaders and rank-and-file members, it means developing the “muscle memory” of legislative give-and-take – not just on symbolic measures, but also on bills that could become law.

For now, Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell is working to recover from the embarrassment of having to call off a vote last week on his chamber’s plan for Obamacare repeal and replace, called the Better Care Reconciliation Act. He and his team have been laboring behind the scenes to rework the bill and garner support. Trump, too, has been making calls to senators, according to top administration officials.

No one said replacing the ACA, or Obamacare, would be easy. The Republican majority in the Senate is slim – 52 to 48. That means the party can lose only two votes, with Vice President Pence breaking a tie.

And President Obama’s signature reform has grown in popularity since Trump took office, as support for the GOP replacement loses altitude. A Fox News poll taken last week shows only 27 percent of registered voters favor the Senate bill, its best showing among the latest polls.

The Republican effort to replace the ACA has been a giant game of “beat the clock” – in part by design. Trump himself wanted fast action, as promised during the campaign. In addition, the Republicans are attempting to replace the ACA via a legislative technique known as reconciliation, which requires only a majority to pass, but can be used only once per fiscal year. That gives the party until Sept. 30, which isn’t much time, given the legislative calendar.

Senator McConnell wanted his colleagues to vote quickly, a week after the bill was unveiled and days after the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office had issued its report laying out the projected impact. But aside from the Trump imperative, and the legislative calendar, why the effort to move so quickly?

“It’s a rendezvous with arithmetic,” says John Pitney, a political scientist at Claremont McKenna College in Claremont, Calif. “When you’re restructuring a significant chunk of the economy, the costs suddenly come to the fore.”

Professor Pitney points to reduced funding for Medicaid, health care for low-income Americans, and other changes to coverage via the exchanges. “The longer this plays out, the more you’re going to hear from people who stand to suffer,” he says.

Some senators have already faced confrontational voters at town halls, and more such exchanges can be expected. Republicans defend the legislation as a market-oriented remedy to a collapsing ACA, aiming to bring down premiums and allow consumers more choice.

McConnell’s memoir is called “The Long Game” for a reason. Known as a smart political tactician, he could shelve health-care reform and come back to it later. House Speaker Paul Ryan, after all, failed to bring his first version of repeal and replace to a vote, and later succeeded. McConnell could do the same. In the meantime, the ACA would remain in effect, and blame for its deficiencies would fall on Democrats. The Republicans could then move on to tax reform – a legislative initiative that Trump reportedly sees as his most important.

But without health-care reform, pressure would be even higher to notch a major legislative success. And with reports that populist White House adviser Steve Bannon wants to raise the 39.6 percent tax rate on the highest earners – those who earn more than $418,400 a year – tax reform may be even more difficult than previously thought.

Of course Trump has plenty to show for his short time in office. He got the Senate to confirm a conservative judge, Neil Gorsuch, for the Supreme Court – albeit aided by a historic rule change ending the filibuster for high court nominees. Trump’s controversial travel ban to the US for citizens of six largely Muslim countries was allowed to go into effect, with some exceptions, ahead of a full hearing by the Supreme Court in the fall. And through both executive action and legislation, the president has eliminated dozens of government regulations deemed a burden on the economy.

But it’s the delicate business of enacting big, complicated legislation that may be most confounding in a new era of unified government.

“The difference between the two parties is that the Republican Party is so good at campaigning and so bad at governing, or at least at passing legislation,” says Cal Jillson, a political scientist at Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

Michael Bailey, a professor of American government at Georgetown University in Washington, says it’s not even fair to blame ideological diversity within the GOP for the party’s challenges. In this era of partisan polarization, the most liberal Republican is still more conservative than the most conservative Democrat, studies show.

“The Republicans are pretty strongly conservative – even the quote-unquote moderates are pretty conservative,” says Professor Bailey. “They don’t have big ideological divisions, and they don’t have big geographic divisions…. So it’s all the more amazing that they’re having these troubles.”

Share this article

Link copied.

In Hong Kong, growing concern over a culture’s erosion

Hong Kong has long held an outsize importance. It is a laboratory for Chinese democracy. But 20 years after China took control of the city, there are mounting signs that this uniqueness is under threat.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Michael Holtz Staff writer

As a fireworks display burst over Hong Kong Saturday night, marking the 20th anniversary of the city’s handover from Britain back to China, characters for the word “China” lit up the sky. But in this semiautonomous city, where concerns about the mainland’s growing influence are widespread, even those two characters were loaded with controversy: They were written in the simplified characters of the mainland, rather than the traditional characters used in Hong Kong. It’s one more subtle sign, for many Hong Kongers, that their city’s distinct cultural identity is at risk. Meanwhile, concerns are growing that Beijing will increase its political influence – concerns underscored this weekend by President Xi Jinping, who warned that challenging the central government “crosses the red line,” hours before Hong Kongers took to the streets for an annual pro-democracy protest. “People are worried that Hong Kong is becoming just another mainland city,” says Stephan Ortmann, an assistant professor at the City University of Hong Kong.

In Hong Kong, growing concern over a culture’s erosion

Wing and Gabbie Wong had been thinking about moving abroad even before Chinese President Xi Jinping’s speech here on Saturday. But Mr. Xi’s stern warning against challenging Beijing’s rule over the semiautonomous city reaffirmed many of their greatest fears.

“We want to protect our way of life, but it’s getting harder year by year,” says Mr. Wong, a salesman for a fashion company. “Hong Kong is losing its identity.”

And so he and his wife want to move to Japan, where a friend has offered to help them apply for work permits and open a coffee shop. Ms. Wong says that at least there they could raise their 18-month-old daughter free from mainland China’s growing – and, in her and her husband’s minds, corrosive – influence.

Twenty years after Hong Kong’s reunification with China, many residents in this prosperous global city say much of the change that has occurred since then hasn’t been for the better. Soaring housing costs and widening inequality are among their top concerns, but many are equally nervous about the threat mainland China poses to Hong Kong’s culture and identity.

“People are worried that Hong Kong is becoming just another mainland city,” says Stephan Ortmann, an assistant professor at the City University of Hong Kong. “The city is dying for many of them.”

Beijing's red line

Xi exacerbated those concerns in the speech he delivered at this weekend's anniversary ceremony, marking the anniversary of the 1997 day that Hong Kong was returned to China after more than 150 years of British rule. Under the arrangement known as “One country, two systems,” Hong Kong was supposed to retain relative autonomy and civil rights for the next 50 years.

While the Chinese leader acknowledged Saturday that the city is a “plural society” with “different views and even major differences” from the mainland, he also said that its liberal way of life has its limits.

“Any attempt to endanger China’s sovereignty and security, challenge the power of the central government ... or to use Hong Kong to carry out infiltration and sabotage against the mainland is an act that crosses the red line and is absolutely impermissible,” Xi warned.

The speech was a clear message to the tens of thousands of people who took to the streets Saturday afternoon in an annual pro-democracy protest. Implicit in their calls for freedom of speech and self-determination was a deeply rooted desire to preserve Hong Kong’s way of life, one that has long been defined in opposition to the mainland.

“We want to have freedom,” says Alex Chan, a 35-year-old nurse who joined in the “Umbrella Movement” in 2014 to demand free elections. Nearby, a group of people carried a banner calling for the release of Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo, who was recently moved from prison in northeast China to a hospital for cancer treatment.

Many of the people who marched on Saturday say their freedom is under threat by Beijing’s increasing control. They point to a series of recent interventions by the central government that they say violated Hong Kong’s mini-constitution, known as the Basic Law, and promoted a climate of fear.

One of the most prominent cases occurred in 2015, when Chinese authorities appear to have abducted five booksellers who sold gossipy stories about mainland officials. Similar suspicions were raised earlier this year when an influential billionaire, Canadian citizen Xiao Jianhua, went missing from his hotel suite. And late last fall, Beijing intervened in Hong Kong’s independent legal system to block two pro-independence politicians from taking their seat in the city’s legislature.

Hong Konger first

Sonny Lo, a political commentator in Hong Kong, says Beijing’s heavy-handedness has led more and more young people to distance themselves from the mainland and to see themselves as Hong Kongers first and foremost. Only 3.1 percent of those between 18 to 29 years old identify themselves as broadly “Chinese,” according to a University of Hong Kong survey released last week. The figure stood at 31 percent in 2006.

They’ve also grown to resent the mainland Chinese who have poured money into Hong Kong’s housing market and made it one of the world’s most expensive places to live. The rising cost of living has squeezed young people and middle-class families especially hard. Unable to afford a place of their own, Mr. Chan and his wife have rented an apartment from one of his relatives for the last 10 years.

Then there’s the rising anxiety about language. Longtime Hong Kong residents say it was rare to hear Mandarin, the official language of China, on the streets a decade ago. Now, with the influx of mainland tourists, it has become common. Cantonese is still the “usual language” for 89 percent of Hong Kong residents. But big international companies and banks increasingly prefer to hire fluent Mandarin speakers who can help negotiate deals on the mainland.

Growing sensitives over language extend to politics as well. Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s newly selected leader, took her oath of office and delivered her inaugural address in Mandarin after Xi’s speech on Saturday. She spoke briefly at the end in Cantonese. Later that night, a fireworks display included simplified characters for the word “China” rather than the traditional characters used in Hong Kong, a move that was widely criticized here.

Looking ahead

As divisions over identity and culture deepen with the mainland, Hong Kong’s separatist movement continues to grow – as well as pressure to put an end to it. Xi’s speech hinted that he wants the city’s government to introduce new legislation against subversion, which critics fear will provide a pretense to rein in criticism of Beijing. He also said Hong Kong should “step up the patriotic education of young people,” a highly controversial idea. Mass protests shelved a similar plan in 2012.

Victoria Hui, a political science professor at the University of Notre Dame who closely followed the Umbrella Movement, says young people are sure to resist. Many have already started to question Beijing’s commitment to “One country, two systems,” doubting that the central government will allow Hong Kong to maintain its own legal, economic, and local political systems until 2047. Even if the central government does uphold its side of the agreement, what happens then?

“For me, I’ll likely be dead,” says Dr. Hui, a pro-democracy advocate who grew up in Hong Kong. “For young people, this is something real. They can't just allow to have ‘One country, one system.’ For them, everything matters.”

Where deported veterans find support for a fresh start

How do you undo a mistake? Unauthorized immigrants who served in the United States armed forces but then were deported for a crime are asking themselves that question. Their answer? Start by helping one another.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

On a quiet street in Tijuana, Mexico, next door to a mechanic shop, is an orange-and-tan concrete building. A line of overstuffed easy chairs are tucked tightly between desks and a television, with a large American flag and photos of soldiers hanging above. This is “the Bunker”: a support center for US veterans deported to Mexico. Reintegrating into civilian life after service can be challenging for anyone, and veterans of all stripes end up on the wrong side of the law. But for those who didn’t gain citizenship during their service, breaking the law can spell deportation after a prison term is up. Many say they aren’t holding out hope that they’ll return home anytime soon. But they’re appealing to US lawmakers for future vets’ sake, and helping their “brothers” here find purpose. “We made mistakes [that got us deported], but that doesn’t mean we have to pay for the rest of our lives,” says Hector Barajas, founder of the Bunker. “If we can’t ever go home, we need to at least do our part to be productive members of the country we’ve been deported to.”

Where deported veterans find support for a fresh start

When José Francisco López was deported from the United States 13 years ago, he felt utterly alone.

Deportees commonly struggle with depression and feelings of isolation, but Mr. López was different. As a legal US resident, he served in the Army for two years – one of which he spent in Vietnam during the war. He was honorably discharged, and was later arrested for buying cocaine and sent to prison. But López paid double for his crime: Once his prison term was complete, he was promptly kicked out of the country.

“I felt sad…. I thought I was the only one,” he says of being a deported veteran, living in the border city of Juárez while his children and mother are across the frontier in Texas.

But late last year, López connected with Hector Barajas, the founder of the Deported Veterans Support House in Tijuana. López was surprised to learn he’s actually one of an estimated 230 deported veterans living in some 34 countries. At 73 years old, he decided to take action, turning the second floor of his modest home into a meeting space and dorm room for other US servicemen deported from the United States. It’s modeled after the Deported Veterans Support House, or Bunker, in Tijuana, which provides camaraderie and connects vets to services like mental health support and legal aid.

“There are so many of us,” López says. “We can help each other move ahead.”

Foreign-born soldiers have served in the US Army since its inception, fighting in every US war. In 2005, some 35,000 noncitizens were serving in the active military, with about 8,000 enlisting each year.

Reintegrating into civilian life after service can be a challenge for anyone, and veterans of all stripes can end up on the wrong side of the law. But, for those who didn’t gain citizenship during their service – whether due to misinformation, bureaucratic mistakes, or misunderstandings – breaking the law can spell deportation after a prison term is up.

Among deportees, vets face unique challenges: from struggles with PTSD and physical injuries, to criminal gangs that target them for recruitment because of their military experience. Although many deported veterans in Mexico say they aren’t holding out hope that they’ll return home any time soon, they are working to raise awareness, appealing to US lawmakers for future vets’ sake. And in the meantime, they’re focusing on helping their “brothers” here find purpose and a path ahead, outside the country they were willing to risk their lives for.

“Our mission is to make the transition a little better,” says Iván Ocon, who recently joined López in directing the Juárez Bunker. “At the very least, we can let them know they aren’t alone. We can make the nightmare a little less scary.”

Finding community

Mr. Ocon was honorably discharged in 2004 after more than a decade of service, including time in Jordan during Operation Iraqi Freedom. But it was a tough adjustment. He couldn’t hold down a job, and became depressed, leading him toward drugs and alcohol. He asked about the status of his citizenship while in the armed services, he says, and was told it was on track. After six years in prison for aiding and abetting a kidnapping, he learned that wasn’t the case.

He doesn’t recall the judge’s exact language at his immigration hearing, but says the message was loud and clear: “My military service didn’t count for anything.”

“I felt betrayed,” he says.

Many deported vets have similar stories. Some say they were promised citizenship by Army recruiters, only to face labyrinths of red tape with little guidance. Others misunderstood the oath taken to protect and serve the country when they joined the Army, believing it automatically made them a citizen.

Many found support and created a network after learning about the Tijuana Bunker. It’s an orange and tan concrete building on a quiet street in Tijuana, next door to a mechanic’s shop. The glass around the front door is covered in fliers about deported veterans and Dreamer Moms, another group of deportees who share the space. On the ground floor, a line of overstuffed easy chairs are tucked tightly between two desks and a television set. A large American flag hangs above the chairs, along with photos of soldiers and posters calling for access to pensions and health care. Upstairs, dorm-like bedrooms with single beds covered in fuzzy blankets house veterans in transition.

“The housing is important, but we’re more of a resource center,” Barajas says. “We work to help secure [Veteran Affairs] benefits, help get [Mexican] IDs, find people lawyers while they’re still in the US facing deportation. We’ve even helped someone get a prosthetic foot.”

Many younger vets struggle with PTSD. The veterans also frequently face new variations of discrimination. “My whole life in the United States I was called a Wetback, and now in Mexico I’m called a Gringo,” says López.

Depression is overwhelmingly common, and Barajas says he often gets calls about suicidal veterans. Ocon, in Jaurez, can relate to that.

“I found out the only way they will take us back [into the United States] is in a body bag, and I thought, well, maybe that’s the way,” Ocon says, referring to the US policy to bury veterans – even those who have been deported – in VA cemeteries.

'No longer under the radar'

The deportation of veterans began to pick up around 1996, when the US changed its immigration laws, taking away a judge’s discretion to consider factors like military service in deciding a case, says Jennie Pasquarella, director of immigrant rights for the ACLU in California and co-author of a July 2016 report on deported veterans.

But thanks to the work of deported veterans led by Barajas, the issue is “no longer under the radar,” Ms. Pasquarella says.

Last month, a group of seven US Congressmen visited the Tijuana Bunker to learn about the experiences of deported veterans. A bill was reintroduced in Congress in March that would provide support for future possible deportees and provide a pathway home for veterans who have already been deported. So far, it has the support of 51 lawmakers.

Many of the veterans seeking support from the Bunkers draw a direct line between their crimes and the challenges they experienced reintegrating into society after military service.

“We made mistakes [that got us deported], but that doesn’t mean we have to pay for the rest of our lives,” says Barajas, who was brought to the US as a child and gained legal residency. He enlisted at 18, and spent six years in the Army. But his honorable discharge was followed on by drug addiction, and eventually a shooting crime that would land him in prison for three years.

“We have to take responsibility for our actions. We have to try to change those laws,” he says. “If we can’t ever go home, we need to at least do our part to be productive members of the country we’ve been deported to.”

The Bunker has had some success stories, like the vet who received his pension after years of fighting.

“It’s not that you’re jealous, but sometimes I do wonder, ‘What about me?’” says Barajas, who has been doing this work since his 2010 deportation.

Earlier this year, however, he got something “worth more than a million dollars:” He and two other veterans were pardoned for their crimes in the state of California. There’s still no guarantee he’ll return to the US, he says, but the pardon was an important step.

“Most of us are never going home,” Barajas says. “What can we do? Be negative? No. We just keep pushing forward.”

How to curb rise in ‘space junk’? Scientists eye the feet of geckos.

This next story has the ring of a real-world "WALL-E," the Pixar film in which we pollute ourselves off planet Earth. Here, the issue is junk in space. And the good news is that scientists are coming up with creative answers.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

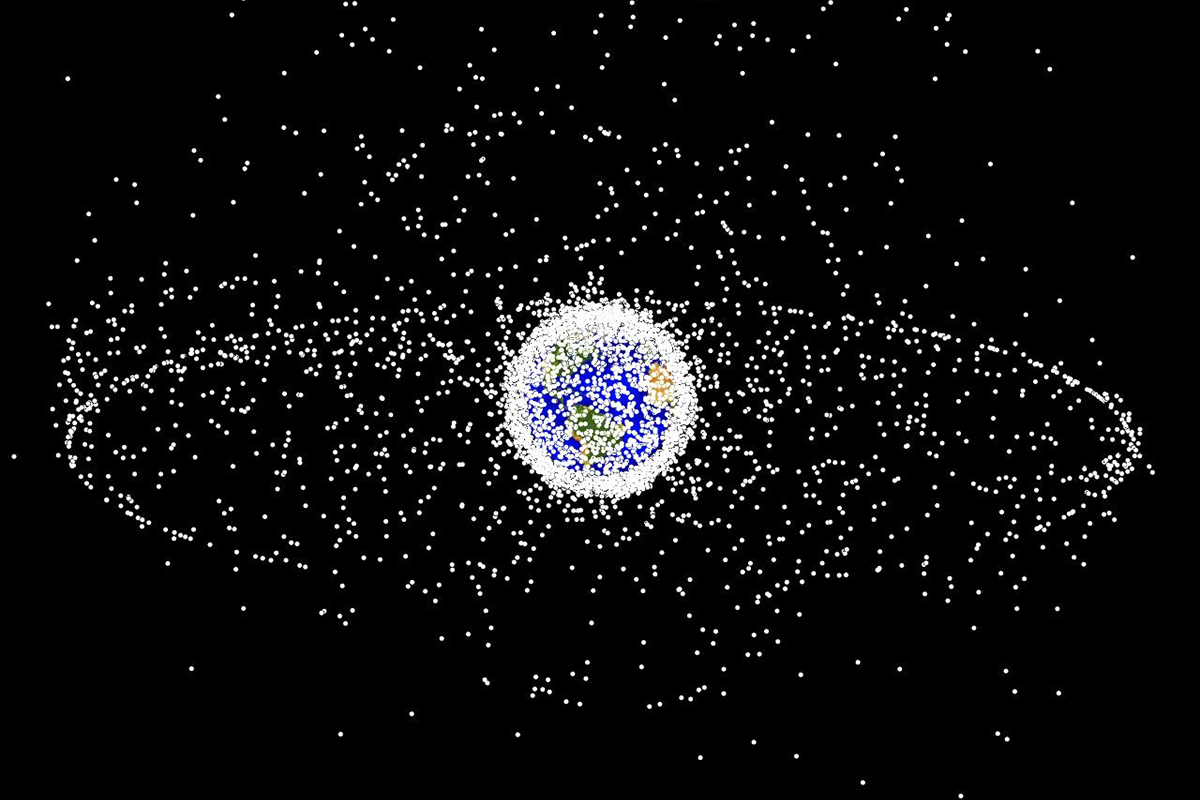

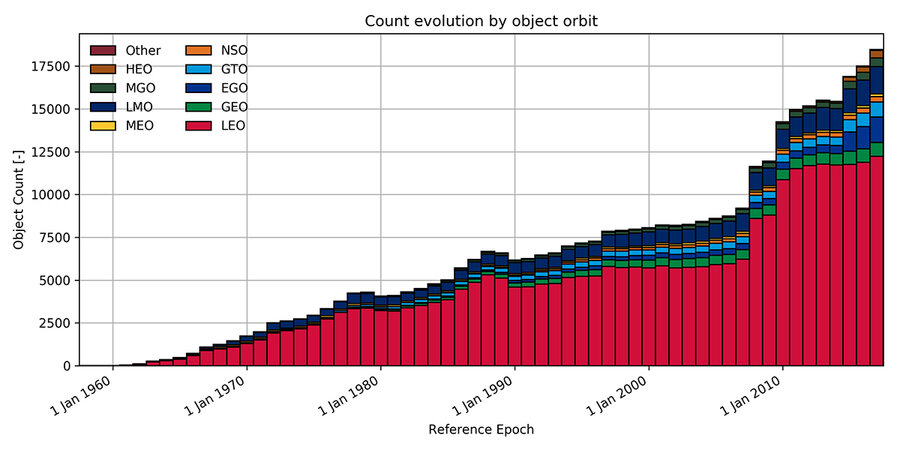

In recent decades, Earth has accumulated a peculiar kind of halo, with more than 1,000 satellites that study the planet, provide navigation signals, and beam TV to millions down below. The explosion of orbiting equipment has brought a new engineering challenge: How to keep low-Earth orbit from becoming an orbital minefield littered with decommissioned space junk. The Department of Defense catalogs tens of thousands of artificial objects around Earth, with fragments likely numbering in the millions. Some researchers are focusing on harpoons and nets to rein in the space junk. But a collaboration between Stanford and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory is focusing on a more earthly solution: grippy pads inspired by gecko feet. Experts urge action before the splintering of satellites makes space unusable, but so far at least, governments aren't leaping at the opportunity to fund retrieval efforts. As JPL's Aaron Parness puts it: “We’re building the technology so that whenever the decisionmakers decide ‘it’s time,’ we’ll be ready to go.”

How to curb rise in ‘space junk’? Scientists eye the feet of geckos.

It was satellites that launched the space age, and it’s satellites that could bring it all crashing down.

More than 1,300 circle above our heads, providing navigation signals, studying the planet, and beaming TV to millions. Few communications pass directly through space networks, but if not for the nearly three dozen atomic clocks providing reliably precise timestamps to anyone with an antenna, financial markets and cell service would quickly fall apart.

It doesn’t take much to reduce these finely tuned machines to thousand-pound wrecks. With life expectancies rarely exceeding a decade, the engineering marvels are surprisingly disposable. And as new arrivals and old relics crowd the useful, near-Earth orbits, governments and researchers seek ways to restore space’s once infinite promise. A smorgasbord of proposals includes slowing the depleted spacecraft with ground-based lasers so that they fall to a fiery end, and flinging them down directly with sling shots, nets, and whips. As yet, though, no one’s reaching for the checkbook.

“Everybody recognizes that this is a problem, and that the problem is getting worse, but it’s not clear exactly whose job it is to clean it up,” says Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) robotics researcher Aaron Parness.

Now, a collaboration between Dr. Parness’s JPL group and a team of Stanford engineers suggests this man-made problem might have a nature-inspired solution: gecko-like pads sticky enough to grab objects in the harsh vacuum of space.

Orbital minefield

What goes up must come down, unless it’s traveling more than 25,000 miles per hour. Of those objects that make it into orbit, air resistance eventually drags down most, but some trajectories can keep others whizzing around for decades.

The Department of Defense catalogs tens of thousands of artificial objects around Earth, but fragments too small to track likely number in the millions. Any one of these hyper-speed projectiles could cause impact damage ranging from divots to explosions.

One big target is the International Space Station, which routinely takes hits from sub-millimeter sized particles and actively dodges larger bits multiple times each year.

Often asked if @Space_Station is hit by space debris. Yes – this chip is in a Cupola window https://t.co/iH87Dt80yV pic.twitter.com/7ZvVs4myM0

— Tim Peake (@astro_timpeake) May 12, 2016

And smaller spacecraft are in danger too. In 2009, a US commercial satellite tore through a Russian military satellite, each bursting into a debris cloud that encircled the planet.

Statistical analyses predict these crashes every five to ten years, suggesting the tipping point at which satellite shards destroy other satellites faster than the atmosphere can swallow them up has already passed. NASA astrophysicist Donald Kessler first analyzed this phenomenon, now called the Kessler Syndrome, nearly 40 years ago, and predicted that the emergence of a “debris belt” around Earth could someday halt space activity.

Fortunately, we won’t lose GPS and weather forecasting overnight.

“That’s a popular misconception, that something will trigger it,” Dr. Kessler explains. “It’s more like a very slow chain reaction that plays out over tens of years.”

Focus on 'the big stuff'

NASA’s Orbital Debris Program Office predicts the amount of softball-sized space junk to double within two centuries. Right now, collisions occur once every 10 years or so. But, as Kessler points out, such rare events don’t strictly abide by expected averages: “There’s a significant probability that you could have four collisions within ten years, or you could have none.”

And even one extra breakup makes a huge difference. Two events, the 2009 collision and a 2007 Chinese anti-satellite weapons test, account for more than a quarter of the currently tracked fragments.

Retrieving such shards is nearly impossible, leaving only one practical solution. “Get rid of the big stuff. Get rid of the source,” Kessler urges.

Space agencies have a narrow window in which to act, and they’re trying – to some extent, at least. NASA has almost completely put a stop to spent rocket explosions, once the largest debris source.

Thirteen agencies joined together to form the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC) in 1993, which issues disposal guidelines for satellites. But these are suggestions rather than requirements, and compliance varies.

“The European Space Agency is very strict at enforcing their guidelines,” Kessler says. But since NASA often grants US satellites exemptions, “the US has not been doing very well.”

The good news is, when it comes to active cleanup, some well-placed prevention could be worth thousands and thousands of cures.

Sticking points

The splintering nature of collisions means preventing even a few can significantly slow fragment growth.

NASA simulations estimate removing just two high-risk satellites per year starting in 2020 could halve the two-century growth rate; removing five could stabilize the debris cloud at current levels.

But first engineers have to overcome at least two technical hurdles. The typical defunct satellite is spinning rapidly, and lacks handles to latch onto. Any would-be space trash collector has to be able to stop the object, and then grab it.

While some engineers focus on challenging-to-control harpoons and nets, a Stanford–JPL collaboration takes inspiration from some of nature’s best climbers to solve the latter with a new adhesion system, featured Wednesday in the journal Science.

Most sticky mechanisms break down in extreme vacuums, but geckos exploit quantum weirdness to create a friction-like force between micro hairs on their feet and smooth surfaces. The team’s grabber mimics that behavior, resulting in a device that can grip and release a variety of shapes without pushing them away.

But deorbiting satellites is an expensive business, and Kessler worries too much focus falls on selling concepts rather than buying them. With private aerospace companies and the diminutive “cubesats” driving down the cost of space access, sharing cleanup fees has never been more feasible.

“All you need is something like a 5 percent or 10 percent tax on each launch,” he says. No country has agreed to such a fee so far.

Parness suggests the murky legal status of space complicates cleanup too. “If there’s a Chinese satellite or a satellite from the Soviet Union and NASA goes up there and pulls on it, right now that would break international law,” he explains. It’s every country for themselves.

For now, he looks forward to testing the gecko gripper outside the ISS, and eventually collaborating with satellite servicing missions and private cubesat projects on strategies to address the space trash problem more directly.

“We’re building the technology so that whenever the decision makers decide ‘it’s time,’ we’ll be ready to go,” Parness says.

Barbecue wafts far from its roots in the sunny US South

Your Fourth of July barbecue may well owe its savory smells to Southern slaves, German mustard, French vinegar, and Spanish pigs. Which makes it the perfect American food to take over the world.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

The Fourth of July has finally rolled around, and Americans’ thoughts are turning to outdoor cookery. For some, that’s just about flipping hamburgers. But these days others are devising new secret rubs and sauces and firing up smokers that send an apple-wood aroma through neighborhoods. Barbecue is to American food what jazz is to American music – a distinct art form with African-American roots that cuts across socioeconomic and demographic barriers, uniting more than dividing, but also maintaining regional differences. It has migrated out of the South and across the country, becoming as hot as a hickory ember. That’s evident in the rise of restaurants, backyard gatherings, professional competitions, and new pit technology. And it doesn’t end at the US borders. Southern-style barbecue is showing up in restaurants from China to France. “The barbecue renaissance,” says one food historian, “is now global.”

Barbecue wafts far from its roots in the sunny US South

It’s a quiet morning on a crook in the Mississippi River, not too many miles from where Hernando de Soto feted members of the Chickasaw Indian tribe with the first American barbecue in 1540.

More than 200 white tents are spread out beneath a bluff, where some of the world’s best pitmasters have gathered to claim a piece of barbecue immortality – by smoking parts of a hog that they hope will win them recognition at the annual World Championship Barbecue Cooking Contest. A cool river breeze carries the scent of charred meat as the pitmasters open the lids of smokers to reveal glistening baby back ribs and pork butts.

Inside one tent, Marlando Cason quietly but intensely oversees a crew of 10, some of whom have been up all night cooking 200 pounds of pork shoulder. The pieces were cut from a special breed of pig, injected with a tamarind brine, and dusted with a fiery rub.

A Bunyan-size man in bib overalls, “Big Moe,” as he’s called, inspects the blackened piece of meat that has been smoking in a wood-fired cocoon for 12 hours. It has reached just the right internal temperature, 201 degrees F., that allows the pockets of fat to melt and percolate through the shoulder, producing a taste that the cooks hope will be transcendent for nine judges and maybe the competitors’ lives.

While Big Moe dotes on the pork, others on his team prepare the final ingredient – the barbecue sauce. They whisk together apple cider vinegar, red pepper jelly, and a concoction from a jar whose ingredients – like most pitmasters’ ingredients – are as secret as a CIA cable.

“Is it good?” asks one team member.

“It’s good,” says another.

“A little sweet,” worries a third who’s used to a tangier sauce.

As the Fourth of July weekend approaches, Americans across the country will be summoning their own inner pitmaster.

They may not be putting quite as much attention into their brisket and baby back ribs as Big Moe and his crew typically do. But thousands of Americans, nonetheless, moved beyond just flipping hamburgers and hot dogs a long time ago. They are now developing their own secret rubs, devising barbecue sauces out of beer and brown sugar, and firing up smokers that send their apple-wood aroma through neighborhoods.

What started out as a Southern phenomenon – “real” barbecue – has migrated across the country, becoming as hot as a hickory ember. It is evident in the rise of restaurants, backyard gatherings, professional competitions, new pit technology, and would-be Big Moes slathering pork with their own mop sauces.

Nor is the fascination limited to the United States. Southern-style barbecue is showing up in restaurants from China to finicky France. The only difference is that in Paris the main side dish isn’t beans or slaw. It is smoked cauliflower drizzled with chorizo vinaigrette.

“The barbecue renaissance is now global,” says John T. Edge, author of the just-released book “The Potlikker Papers: A Food History of the Modern South.”

That probably shouldn’t be surprising since barbecue is intertwined with the history, politics, and culture of the US as much as any other cooking style. It is to American food what jazz is to American music – a distinct art form with African-American roots that cuts across socioeconomic and demographic barriers, uniting more than dividing, but also maintaining regional differences.

Its current popularity stems in part from the mystique surrounding some of its impresarios, people like Big Moe, a water treatment plant operator who has risen to become something of a celebrity pitmaster. But even Big Moe knows that, with all the vagaries involved in smoking a piece of meat, there’s always a bit of mystery as to how it will come out. Which is why, as he gets ready to send the slices of pork shoulder off to be judged, all perfectly displayed in a plastic foam box, he addresses his crew with a mixture of confidence and hope.

“We’ve got this,” he says. “We’ve got this.”

Big Moe has a look that exudes barbecue cool. He stands more than 6 feet tall, with a frame that seems tailor-made for overalls – which he calls his “soft clothes” – and wears heavy gold jewelry.

He is drawn to barbecue for some of the same reasons a growing number of other people are: its authenticity and sense of tradition. Big Moe, who is African-American, says he’s the beneficiary of a long lineage that began in the South with African slaves creating barbecue from the scraps of their masters’ tables.

It started to move north in the early 1900s when a young black man, Henry Perry, brought the smoke-style of cooking from Memphis to the stockyards of Kansas City, Mo. From there, the largely African-American tradition spread farther to places such as Des Moines, Iowa, where Big Moe grew up.

“Barbecue is ... so popular, and it’s such a way of life, that it has no choice but to spread,” he says.

He might have added that it’s alluring because of its unpretentiousness and relative simplicity. True, there are the complex rubs, the physics of the fire pit, the different woods that perfume the meat with different flavors of smoke, the barbecue sauces that change with longitude as you move across the US – from the vinegary sauces of North Carolina to the sweet, tomato-based ones of Kansas City.

But at its core it is a primal process: a piece of meat cooked slowly in a smoker. Kevin Kuruc, a French-trained chef who is one of Big Moe’s competitors here, says barbecuing reflects a “simplicity that is its complexity.”

Yet despite all the set mechanics involved in cooking the meat, there’s an artistry to the process, too. Veteran pitmaster Jeff Spurgeon, a Big Moe team member who owns a Kansas City auto body shop and cooks in a “trash-can pit” with a painting of Johnny Cash on it, notes that “90 percent of the guys cooking barbecue use the exact same ingredients, yet no two plates ever taste alike. You just know whose food you’re eating. It’s an expression.”

In an age when fantasy football may surpass real football in popularity, barbecuing embodies an eat-with-your-hands realness. It’s what sends many people to the simple barbecue shacks that populate the South and increasingly the North. Customers from all backgrounds and ZIP Codes commune around benches with sticky tablecloths, watching a pitmaster labor next to a creosote-covered pit with cast-iron doors.

“That kind of knowledge and ability to coax tenderness and flavor out of a hunk of meat is in its own way a kind of mysterious art – that beneath billows of smoke and in close proximity to a fire, a cook, a pitmaster ... comes out with a perfectly roasted pork shoulder and rack of ribs,” says Mr. Edge, the author, who is also director of the Southern Foodways Alliance in Oxford, Miss., which studies the food culture of the region. “That mystery is compelling, and it’s one of the reasons we’re attached to barbecue.”

The other reason for barbecue’s current éclat may be a more artificial one – television. The proliferation of TV shows about cooking has propelled the foodie revolution in the US in general, but it has contributed to the mystique surrounding the art of smoking as well. Programs such as “BBQ Pitmasters,” in which a handful of cooks compete to create the best ribs or pulled pork, have helped make every weekend griller want to be a pitmaster and has turned real pitmasters into luminaries.

Big Moe knows the power of the lens. He won an audition to be a contestant on the show and figured it would be a one-off appearance. But his signature look, witty repartee, and penchant for handing out solid smoking tips have made him a popular frequent guest judge.

Soon he became a spokesman for Big Red soda and Little Caesars Pizza – catchphrase: “Certified smokified!” As he walks around the tent city here, people frequently come up and ask to take a selfie with him.

Over the next few months, he will travel overseas as a sort of ambassador of smoke. He has been invited to barbecue events in Sweden, Germany, and Australia. Representing barbecue – and America – “warms my heart,” he says.

The tour underlines the global fascination with smoked meat. Paris, for instance, now has at least two barbecue restaurants, The Beast and Flesh. Holy Smoke BBQ draws well-dressed foodies in Nyhamnsläge, Sweden. Mexico City; Vienna; Shanghai, China; and London all offer real American “cue.” In New Zealand and Australia, Meatstock, a music and barbecue festival, has become a huge annual event.

A few years ago, North Carolina expatriate David Straughan and Kansas City native Nick Jumara were living in China when they ended up in possession of a “sanwenche,” a kind of pedaled pickup, on which they mounted a smoker. They began serving pulled pork and other barbecue to people in the port city of Ningbo. While the two Americans couldn’t communicate what kind of food it was, the Chinese responded in a language that’s universal.

“There is a certain look of affirmation on someone’s face when they’re trying something new and decide that they like it,” writes Mr. Straughan of the experience in the “South Writ Large” blog.

Even though he grew up in Iowa, Big Moe learned about the culture of barbecue the way many Southerners do – from his grandmother. He was one of 17 grandchildren.

“As a young man, I was always intrigued with the grill, cooking on it, experimenting with it – nothing too crazy,” he says. “But that’s how I got introduced to it: My family was all about food.”

He didn’t know anything about barbecue competitions until 2006, when he heard a reference to one on a cable food network. “I was intrigued,” he says.

He took some money he’d put aside from his US Navy pay and bought a smoker. Soon he began competing at Kansas City Barbecue Society (KCBS) events. Within six years, he had earned $80,000 in winnings – serious money for a backyard cook but hardly riches. In a reflection of the realities of a pitmaster on the semipro circuit, he still works full time for the city of Des Moines in the treatment plant.

Still, there are no shortages of competitions for him to enter. KCBS events alone are expanding at a rate of about 25 percent per year. Two years ago, the organization added an international division to its competitions.

The World Championship Barbecue Cooking Contest in Memphis typifies the trend. What was once a down-home quirky affair – a Memphis culture critic recently mused about the time he saw a boy drag a barbecued raccoon through the mud – this year drew 236 teams from around the world, though that is down slightly from 2016. That includes the Norwegian National Barbecue Team, which counts among its members the king’s personal chef. Pitmasters compete in one of 10 categories – from best whole hog to best ribs to best exotics (think antelope).

Like many teams, Big Moe’s is a hybrid, with people from diverse backgrounds and locations – a reminder of the egalitarian nature of barbecue. He put out a call for recruits on Facebook and received hundreds of responses. Team member Dave Webb, of Dave’s Sticky Pig in Madisonville, Ky., remembers finding Big Moe’s tent, being introduced, and “promptly forgetting everyone’s name.”

While most had competed before, several were rookies, including Devon Rightsell, a factory worker from rural Missouri. “Yeah, he’s our oddball” as far as competition experience, says Big Moe. “But I just had a really good feeling about him.”

The man who tended the fire all night, “throwing sticks” in the smoker when needed, was Mike Jeffries from Wellington, New Zealand. A few years ago, he toured barbecue shacks across the American South for seven weeks (putting on a few pounds in the process), returned to New Zealand, and opened Big Smoke BBQ. Today he caters tony weddings and high-end corporate events.

Mr. Jeffries met Big Moe earlier this year in New Zealand, where the American was impressed with the Kiwi’s cylindrical fire pit. “I basically met Moe at Meatstock, and he invited me to come [to Memphis],” says Jeffries. “Let me tell you, I did not hesitate.”

While the high-end pits and star chefs down by the river represent the smoking culture’s global spread, Payne’s Bar-B-Q restaurant a few miles away on Lamar Avenue embodies what some worry are the fading roots of an American institution. The restaurant has resisted change, offering only pork – chopped or sliced – served with mustard slaw and beans flecked with more pork.

“This is what people come for, the atmosphere, the food. It needs to feel real,” says proprietor Candice Payne.

Ms. Payne still cooks with charcoal, but more and more old-school joints have abandoned wood for gas and adopted one-taste-fits-all commercialized menus. John Shelton Reed, a retired University of North Carolina sociologist, started The Campaign for Real Barbecue in 2015 to certify wood-fired restaurants. To be sure, he says, the growing popularity of barbecue is helping it evolve in good ways, too, fusing traditional techniques, for instance, with a Millennial penchant for authentic hands-on cooking and farm-to-table sourcing.

“But what’s going away [in some places] is that a lot of Southern old-timey family barbecue places – the kind of place where a whole community goes – have switched to gas entirely,” says Mr. Reed. “[Fiercely regional cuisines have] been replaced with what I call the ‘International House of Barbecue’ model, where the customer is always right, which is not how it’s been traditionally. It’s like in Kansas City, you need sauce and it needs to be thick, red, sweet, with a little bit of heat – in other words, ketchup with stuff in it. It’s the threat of uniformity which I find annoying.”

Craig Whitson, who grew up in Oklahoma but has lived in Norway for more than 30 years, concurs. “The ‘real barbecue’ thing has all happened in the last 10 years,” says the pitmaster for the Norwegian national team, who speaks English with a Scandinavian accent. “Barbecue has got this sort of coolness factor, which I would hate to see it lose. If it got too big, perhaps it would fall to the wayside.”

Concern swirls, too, that barbecuing is shedding its African-American roots. The competition circuit, in particular, is now virtually all white. Many black pitmasters pulled out because the events started to feel like they were too much about money and big sponsors and too little about good pork. Big Moe is at times a lonely torchbearer.

While he understands that any exclusion of black pitmasters is inadvertent, “I am still a bit shocked” by the optics, he says. On his original TV audition tape, he says he told the producers: “You need to mix it up. You ain’t got no color up there.”

The danger is that it can seem like a “white middle-class takeover of black craft and expertise,” says Edge of the Southern Foodways Alliance. That is “something to reckon with.”

Barbecuing, of course, has always been bound up in the politics and race of the nation. Six years before colonists dumped tea in Boston Harbor to protest British tariffs, the royalist governor of North Carolina, William Tryon, tried to appease local militiamen by roasting a whole ox. The men responded by tossing the roast in the river, an act of affirmed loyalties hence referred to as the Wilmington Barbecue.

Later, slaves such as Gabriel Prosser and Nat Turner planned their anti-slavery rebellions at barbecues.

During the Jim Crow years, barbecue joints became emblematic of the segregationist South, as racially distinct as lunch counters. After the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, the Supreme Court ordered Ollie’s Barbecue in Birmingham, Ala., to serve black customers. Owner Ollie McClung had argued that his business wasn’t involved in interstate commerce, so the federal courts, under the Commerce Clause, had no jurisdiction over it. All nine justices disagreed, noting that nearly half of the meat Mr. McClung smoked came from out of state. And it wasn’t until 2014 that the late Maurice Bessinger’s Piggie Park barbecue empire in South Carolina took down Confederate regalia, which was put up in 2000 to protest efforts to remove the Confederate flag from the State House in Columbia.

Even though he is proud of barbecue’s black traditions, Big Moe’s focus at the moment isn’t on civil rights. It’s on civil flavors.

The pork shoulder has come out of the smoker after cooking all night. The team has chosen the tenderest bits of meat, soaked them with pan juice, and applied a glaze of barbecue sauce. The slices glisten in the plastic foam box.

Now it’s a matter of getting the meat to the judges while it’s still warm and by the deadline. Two team members thread their way through the menagerie of tents – one acting as carrier, the other as “blocker” – and deliver the precious cargo.

“We did everything right,” Big Moe tells the team. “I’d be surprised if we don’t walk the stage.”

Most of the cooks scatter to shower and rest before the awards ceremony. Later, a contest official comes by to suggest the team “should definitely” attend the ceremony – a not-so-subtle hint of something to come.

That night, Big Moe’s team takes fifth out of 55 competitors, bested only by a few legendary pitmasters. Big Moe’s cooks walk the stage to raucous cheers. For Mr. Rightsell, the Missouri factory worker, the moment is “life-changing.” He has already started construction on his own pit at home. For Mr. Spurgeon, the body shop owner, creating a championship team out of a group of strangers in three short days is affirmation of barbecue’s ability to not just feed people, but forge relationships.

Big Moe is more expansive. He points out that though Southern slaves were the first legendary pitmasters, there would be no American cuisine without the Spanish, who brought the pigs; the Germans, who brought the mustard; and the French, who supplied the vinegar.

In the end, he says simply, “it’s about keeping true to who you are through a process of cooking.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Hong Kong's uneasy deal with China

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

After Britain turned Hong Kong over to China in 1997, Beijing promised to follow a “one country, two systems” approach. That has meant a great deal of autonomy for the island, including an independent judicial system, unfettered capitalism, and freedom of expression. But Many Hong Kongers say that in recent years the Chinese have been tightening up on those freedoms. What’s next? The older generation in Hong Kong may tread a careful line, politely reminding China of its commitment. But a younger generation, used to Western-style freedoms, has begun talking about full independence. China could learn much about the benefits of democracy from Hong Kong, but it doesn’t seem especially interested now. What Hong Kong can do is continue to showcase the advantages of a more open society, with the hope that someday China will be ready to listen.

Hong Kong's uneasy deal with China

Hong Kong is part of China, now and forever.

That’s the clear message the government of Chinese President Xi Jinping is sending to the former British colony on the 20th anniversary of its return to Chinese rule.

Mr. Xi himself visited Hong Kong over the weekend to make the point. A military parade that featured thousands of Chinese government troops, the largest yet staged on the island, added an exclamation point.

As part of the 1997 turnover from Britain, China promised to follow a “one country, two systems” approach with its new acquisition. That has meant a great deal of local autonomy for Hong Kong, including an independent judicial system, unfettered capitalism, a free press, and personal freedom of expression.

But many of the 7.3 million Hong Kongers feel that in recent years the Chinese ratchet has been tightening, twist by twist, on their freedoms. In late 2014 many took to the streets for 11 weeks in what became know as the “Umbrella Movement,” protesting China’s interference in Hong Kong’s electoral system.

Today the legislature contains members both pre-approved by the Chinese government as well as those independently elected who support democracy and autonomy. The result has often been legislative gridlock: Work on vital issues such as education reform and infrastructure projects has ground to a halt.

Voices speaking for Beijing point to the stalled legislature and ask if a little more Chinese efficiency, and a little less sloppy Western democracy, might be a good thing.

Older Hong Kongers are more likely to tread a careful line, politely reminding China of its commitment that “one country, two systems” will remain uneroded. But a younger generation, used to Western-style freedoms, has begun talking about full independence from China. In a recent poll only 3 percent of 18- to 29-year-olds in Hong Kong consider themselves Chinese. To them Xi’s visit was that of a foreign politician, not the leader of their country.

What next? The leverage would appear to be all on China’s side. It’s made clear that while “one country, two systems” is the policy, it remains subject to broad interpretation by the Chinese government.

China is unlikely to risk any open show of force against its most prosperous urban center. It’s more likely to try to continue to influence events in less obvious ways, including actions against individuals who speak up too loudly.

In his speeches at the 20th anniversary, Xi sought to lower tensions.

“[T]he success of ‘one country, two systems’ is recognized by the whole world,” Xi said. But while this struck a conciliatory tone, he also issued a warning. “Any attempt to endanger China’s sovereignty and security, challenge the power of the central government … or use Hong Kong to carry out infiltration and sabotage activities against the mainland is an act that crosses the red line, and is absolutely impermissible,” he said, according to an account in the South China Morning Post.

Hong Kong’s new chief executive, Carrie Lam, who took office July 1, was China’s favored candidate. She has pledged to “heal the divide and to ease the frustration – and to unite our society to move forward.”

China could learn much about the benefits of democracy from Hong Kong. But it doesn’t seem especially interested now. What Hong Kong can do is continue to showcase the advantages of a more open society, with the hope that someday China will be ready to listen.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Our right to be free

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By Judy Cole

With Independence Day around the corner for the United States, contributor Judy Cole shares some ideas about freedom that can apply no matter where in the world we are. Each of us has the inherent ability to know the creator as good and that we have God-bestowed rights to freedom, including freedom from illness and inharmony. Putting these ideas into practice opens the door to experiencing more of that kind of freedom – as Ms. Cole’s husband found when he was able to put aside his dependence on medical prescriptions and shot treatments, and was completely healed of seasonal allergies he’d struggled with for decades.

Our right to be free

I love the ideas behind the upcoming US Independence Day, celebrating the universal principle that each of us is created free and equal, and that we all possess the same inherent, natural rights that are never to be denied or forsaken. At the same time, I’m reminded how many people in the United States and around the world are looking to be freed from being enslaved by sickness, suffering, and want.

The Monitor’s founder, Mary Baker Eddy, referred to universal rights this way: “God has endowed man with inalienable rights, among which are self-government, reason, and conscience” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 106). Through her deep study of the Bible, she discovered that health is a natural outcome when we exercise these rights.

When my husband began to study Science and Health along with the Bible, he found freedom from seasonal allergies he’d suffered with for decades. He learned more about his true, spiritual identity as the child of God, which isn’t subject to material limitation. He began to take a stand for his God-bestowed right to be free in every department of life. He made an effort to live in a more God-centered way. As a result, he felt he could put aside his medical prescriptions and shot treatments.

That was more than 18 years ago, and he hasn’t suffered with allergies since.

Each of us expresses the spiritual nature and qualities of our creator, divine Spirit. Acknowledging God as universal good and rejecting the belief that sickness and inharmony are facts we have to live with, we can experience more freedom, and be better equipped to help others find their freedom, too.

A message of love

French finery

A look ahead

Thank you for reading, and have a glorious Fourth. We’re off tomorrow for that US holiday, and not publishing. Please check back on Wednesday, when Sara Miller Llana will be looking at the rising global role of German Chancellor Angela Merkel ahead of this week’s G20 meeting in her hometown, Hamburg, Germany.