- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- For ardent Trump loyalists, crisis is no cause to change stance

- As Europe honors US entry into WWI, a warning note on isolationism

- Symbolism, significance: What ice shelf’s breakaway really means

- The other ‘Russia story’: a quiet shift inside Ukraine

- A subject in motion: one state’s revolutionary bid to boost physics

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for July 12, 2017

In 2012, the Monitor’s Christa Case Bryant stood on the sides of a grass field in Saudi Arabia, and watched as a group of girls played a lively game of soccer – Saudi style, meaning it took place in secret, at night, with no men present.

Yet the following year, the country said girls could take sports at private schools. And yesterday, it announced that public schools are allowed to offer gym class starting next year.

In the United States, it’s hard to remember a world where girls and sports weren’t considered a natural pairing. Perhaps it’s not difficult to understand why Louisa May Alcott rattled cages in 1875 with her tale of an uncle who sees that the only thing wrong with his frail niece are her corsets and lack of exercise. But it’s worth remembering that it wasn’t until 1972 that Title IX required equal opportunity for women in school sports.

The Saudi move is part of Vision 2030, which aims to ease various strictures – including on exercise, which just 13 percent of Saudis engage in weekly. Perhaps the girls will lead the way in boosting that figure.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

For ardent Trump loyalists, crisis is no cause to change stance

Some of President Trump's strongest supporters told two Monitor reporters that sure, they have their limits. But they also explained why, so far, they think Mr. Trump is doing exactly what they elected him to do.

-

Henry Gass Staff writer

Waiting for his son outside the Senter Recreation Center in Irving, Texas, Theron Harris, a white-haired Army veteran, says there is a limit to his support for President Trump. So far, that is far from being reached, given that, “I can’t see one thing he’s promised that he’s not trying to get done.” To be sure, the revelation that Donald Trump Jr. emailed “I love it” in response to a Russian offer for dirt on Hillary Clinton comes amid a slight erosion in those who “strongly support” the president. That standard has fallen to about 1 in 5 Americans – down from 30 percent in February – though Mr. Trump still has an aggregated approval rating of around 40 percent. Interviews with Trump voters in Georgia and Texas suggest that part of Trump’s resilience with his core supporters is not just the effect of a media war. It also hinges on the nature of how they see America’s role in the world and the depth of their personal support for the president. “There’s always a deal-breaker” with any president, says Mr. Harris, but Trump “is pro-American … [and offers] a dose of hardcore reality.”

For ardent Trump loyalists, crisis is no cause to change stance

With his rainbow-tinted aviator glasses, Vietnam-era jungle hat, and American flag sleeveless shirt, Tony Carraway comes across as a patriot the way Hunter S. Thompson did: on his own terms, without apology.

A reservist pilot in Conyers, Ga., who flies twin-props in support of domestic Army maneuvers, he turned to President Trump after watching what he saw as years of Democrats starving the military of funding. “Democrats were just going in the wrong direction,” he says. “Trump has set us straight. America wins.”

Now as the Trump White House faces deepening revelations of the campaign’s involvement with Russian intermediaries, Mr. Carraway acknowledges he is among those whose support for the president is being tested.

For now, however, he’s sticking with Mr. Trump, given his view that the media and the Washington establishment are actively trying to undermine an outsider president who was elected to do exactly what he is doing: disrupt the political status quo, shake the economy awake, and recalibrate US interests domestically and abroad.

To be sure, the revelations that Donald Trump, Jr., e-mailed “I love it” to a Russian offer for dirt on Hillary Clinton comes amid a slight erosion in those who “strongly support” Trump. That standard has fallen to about 1 in 5 Americans – down from 30 percent in February – though the president still has an aggregated approval rating of about 40 percent.

Interviews with Trump voters in Georgia and Texas suggest that part of Trump’s enduring appeal to his core supporters is not just them loyally siding with the president in what they see as a war against liberal media. It also hinges on the nature of how they see America’s role in the world and the depth of their personal support for the president.

One Texan named Mary tells the Monitor that, for her, the only unforgivable act for Trump would be “murdering his wife.” But many of his ardent supporters have a more finite line and could be deeply alienated if Trump crosses that threshold, says Charles Bullock, a University of Georgia political scientist.

“The longer this goes, the more evidence that comes up, sure it’s going to peel off some people who today say, ‘The media is out to get him,’ ” he says. “People can deny all kinds of things if they conflict with their deeply held beliefs. But at some point, it’s a final straw.”

The Russia revelations

For Carraway, the Conyers pilot, any obvious evidence of un-American activity would be a wake-up call on Trump.

This week’s revelations and the emails that Donald Trump Jr. released Tuesday, to him, don’t rise to that standard. “[Trump Jr.] didn’t do anything that any other politician hasn’t done. Are you kidding?” he says. While certainly opposition research is coveted by campaigns, there are instances – perhaps most famously in 2000 – when campaigns have called the FBI when handed illegally obtained information.

As far as Russia meddling with US democracy, he explains, “I know they’re not our friends, but things have changed since the cold war. I see Russia now less as some kind of existential threat and more like France.”

'A lot of post-modern chatter'

As the ship of state has turned hard to starboard, there's been a willingness among his supporters to rethink Russia’s role in the world. But even more, says GOP consultant Dave Woodard, it is about Trump’s belief that “part of making America great again is to be the biggest player in the room.”

“It’s a real contrast with Obama, who tried to get along with everybody, and now Trump comes along and he doesn’t mind [annoying foreign leaders],” says Mr. Woodard,the author of “The New Southern Politics.” “If you’re an Alabama fan, you never like Auburn, so if you say something bad about Auburn, well, that’s your job, that’s what you do. In the view of Trump supporters, to be a leader is to be a leader for us and not necessarily a friend to others. And that’s a fact not appreciated many times in the day-to-day press.”

He adds: “Most in his base don’t have any affection for France or Russia or China, so I don’t think he’s getting hurt at all by Democrats trying to paint him with this brush. To a lot of them, this is just a lot of post-modern chatter.”

Waiting for his son outside the Senter Recreation Center in Irving, Texas, Theron Harris, a white-haired Army veteran in a thin-checked shirt, says there is a limit to his support for Trump. So far, that is far from being reached, given that, “I can’t see one thing he’s promised that he’s not trying to get done.”

Some legal experts say soliciting a “thing of value” from a foreign power in the middle of a campaign tests federal law that expressly forbids such exchanges. And on Tuesday, Mr. Trump, Jr.. said he might have done thing differently if he had a do-over.

But the possibility of legal problems for the president's son strains against “the mileage [Trump got] out of the countries that were giving money to the Clinton Foundation, and which looked like a backdoor bribe,” says Woodard.

'There's always a deal-breaker'

But he adds that Trump so far scores only 9 out of 10 on the success scale. “There’s always a deal-breaker” with any president, says Harris, but Trump “is pro-American … [and offers] a dose of hard-core reality.”

To lose Harris’s support, Trump “would have to turn into Obama,” he says, explaining that means Trump would “have to work with Iran, let North Korea keep doing what they’re doing, let Russia do what they want.”

Such views are partly tied to the emotional connection that many people have made with Trump's presidency. That way, “you don’t see a concern with a foreign power impacting our elections, because to acknowledge that is to diminish your hero,” says Professor Bullock.

In Texas, as in other states, party affiliation strongly determines whether people believe Russian meddling is a big deal: 9 percent of Republican voters said Russia influenced the election; 81 percent said it didn’t, according to the latest University of Texas/Texas Tribune poll. Among Democrats, 75 percent said the Russians influenced the election, and 9 percent said they didn't.

At the Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 4380 in Plano, support for the president remains strong. "I'm glad he's stirring up everything, and not taking crap from other countries,” says Steve, who asked that his last name not be used, and jokes that Plano is home to about five Democrats, total.

'Our wild card'

Some Trump fans see, in fact, less hero and more “our wild card,” writes New Jersey construction company owner Jason Roamer via email.

An independent who had never voted before 2016, Mr. Roamer says he began to gravitate toward Trump based on “how the media took everything this man said out of context and twisted it against him in the least honest way possible. Perhaps I felt bad for him.”

Of Russia’s meddling in the 2016 election, “This is something the US does pretty much in every country on earth so I really don’t think we have much room to talk,” says Roamer. “And if Russia is responsible for keeping Hillary Clinton from becoming the next president, I thank them for their service to the citizens of this country.”

He hedges a bit. “There is a line [Trump] could cross,” Roamer says. “I just don’t believe everything I read, so I probably won’t know when it happens.”

Share this article

Link copied.

As Europe honors US entry into WWI, a warning note on isolationism

A century later, a somber anniversary highlights the benefits of cooperation – and connection.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Historians are quick to make comparisons between the populism and xenophobia of today and the atmosphere of the 1930s. But comparisons with World War I are just as apt, particularly regarding the United States: disillusionment with war and unbridled globalization, fueling an instinct to turn inward. When President Trump takes his place as guest of honor on the Champs-Élysées on Friday to watch US soldiers march with French troops in the annual Bastille Day parade, he will be commemorating the 100th anniversary of the US entering WWI. But his invitation is also an effort by the French government to prevent the sort of isolationism that existed in the US before entering WWI. “[Trump] sometimes takes decisions that we disagree with, on climate change for example,” French government spokesman Christophe Castaner told TV channel LCI. “But we can do things: Either you say ‘we're not speaking because you haven't been nice,’ or we can reach out to him to keep him in the circle.”

As Europe honors US entry into WWI, a warning note on isolationism

When President Trump takes his place as guest of honor on the Champs-Élysées on Friday to watch US soldiers march with French troops in France’s annual Bastille Day parade, he will be commemorating the 100th anniversary of the US entering World War I.

But the “doughboys,” as American troops were called in WWI, weren’t there for most of the conflict. As war was raging in Europe, American President Woodrow Wilson was campaigning for reelection with the slogan, “He Kept us out of War/ America First.” Some of the bloodiest battles of the war – in fact, of history itself – were playing out. In 1916, at the Battle of the Somme, more than 1 million British, French, and German soldiers were killed or wounded – and Americans were adamant about not getting involved “over there.”

Today, visitors to the now grass-covered trenches mark the sacrifices of those who were there. For Loralea Wark, a social studies teacher from the Northwest Territories visiting with a group of fellow Canadians, the parallels of an America then and now, pulling away from the world, are discomfiting.

“This is what happens when we don’t cooperate,” she says, pointing to fields that were once sloughs sliced with furrows, and now comprise the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial.

This site is particularly moving because it allows visitors to walk through the trenches, which have naturally filled in over time but still run six feet deep. As scars of the Battle of the Somme, they let visitors glean a physical understanding of soldiers’ inability to advance to the enemy line, from the first day of battle on July 1, 1916, to the battle’s end 141 days later.

“Our generation owes it to these troops. We are here because of what they did,” Ms. Wark says.

Questioning the basic architecture

French President Emmanuel Macron’s decision to host Mr. Trump has been criticized in some circles. They say the US leader, who in his nationalist inauguration speech proclaimed “From this moment on, it’s going to be America First,” is undeserving of the pomp of Paris’s annual Bastille Day parade.

But Mr. Macron is hoping that his invitation will mark a turnaround: that Trump’s positions on trade, borders, security – and key from the French president’s vantage, the Paris climate accord, from which the US pulled out – could get a rethink after his state visit. After all, if President Wilson won the 1916 American election on an isolationist pledge, he entered “The Great War” just weeks after his inauguration, a key to the Allied victory a year and a half later.

In fact, Wilson’s vision behind the League of Nations – even as the US retreated deep into isolationism between the world wars and refused to join the body – gave shape to the postwar order that has dominated, until now.

With the march of nationalist populists and xenophobia in the West and questions about open borders, historians are quick to make comparisons between today and the 1930s. But in many ways those between today and WWI are just as apt: a disillusionment with war, with unbridled globalization, fueling an instinct to turn inwards.

Brian Balogh, the co-host of the podcast Backstory and a history professor at the University of Virginia, says there’s never been a timelier moment in history to reflect on World War I. “The pre-World War I Woodrow Wilson who campaigned on keeping the US out of the war, that Woodrow Wilson was very consistent with America’s history up to that point, going all the way back to George Washington,” he says. The US was an avid free trader, but at that point only maintained a small army. “World War I really marks a watershed in terms of America’s permanent engagement with the world, especially militarily,” he says.

More than 2 million American troops arrived on the Western Front between 1917 and 1918, and their entry was key to boosting the morale of the Allies, who were ultimately victorious.

And now, Dr. Balogh says, “Donald Trump is questioning the basic architecture that has been in place for roughly a century.”

'There are still links'

French government spokesman Christophe Castaner told TV channel LCI that the invitation extended to Trump is meant to honor America’s role as Europe’s liberator in both world wars – but that perhaps it can serve to bring Europe and the US back to the same page.

“There’s also a strong political dimension. Emmanuel Macron wants to try to prevent the president of the United States being isolated. [Trump] sometimes takes decisions that we disagree with, on climate change for example,” Mr. Castaner told the station. “But we can do things: either you say ‘We're not speaking because you haven’t been nice’ or we can reach out to him to keep him in the circle,” he explained.

Gauthier Marseille, a guide for the Museum Somme 1916 in the town of Albert – also known as the town of the “leaning virgin” because German artillery tipped over the gilded statue of Mary atop its basilica – says he also worries about the parallels between the “America First” of then and now.

“Of course the figures aren’t the same, but the [US] is today a country that wants to go back to protectionism, make its economy work and [say] ‘So what’ about the others,” he says. “Donald Trump wants to make things good for Americans, and the rest are cast aside.”

The museum, housed in a 32-foot-deep, 250-yard-long tunnel that served as a bomb shelter during World War II, traces life for soldiers in the trenches of the Somme. Because Americans only entered this area in the Second Battle of the Somme, a much smaller clash in 1918, they aren’t represented.

He supports Macron’s invitation to Trump. “I think it’s good because the Americans helped us in 1917, and we cannot forget it. They came for the Second World War. And despite everything, they have always been our allies, since [the Marquis de] Lafayette,” he says, referencing the French military officer who fought in the American Revolutionary War. “Even if Donald Trump and Emmanuel Macron aren’t in agreement on many points, there are still links between our countries. And I think it’s a good idea he comes here.”

“It’s not because he has different ideas that we should turn our backs on him,” he adds. “Maybe this is a way to find agreement, a way to stay open, and stay intelligent.”

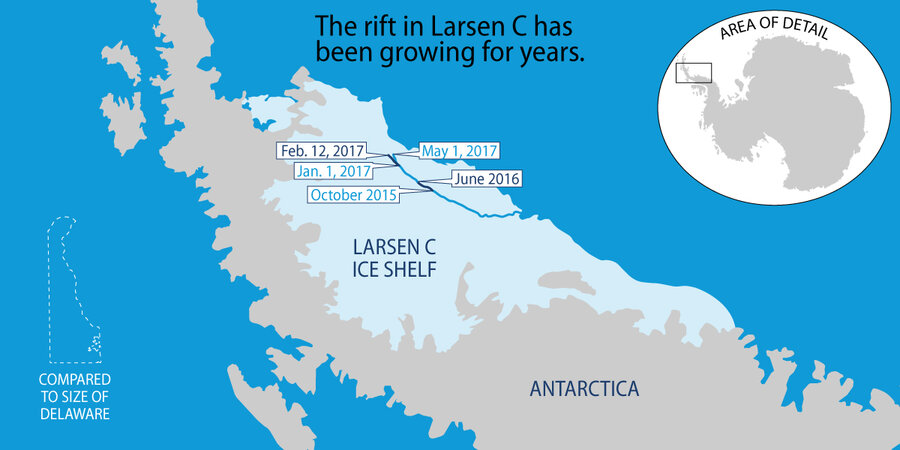

Symbolism, significance: What ice shelf’s breakaway really means

A stunning development in Antarctica could prompt people to leap to certain conclusions. The Monitor's Amanda Paulson explains why they shouldn't.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

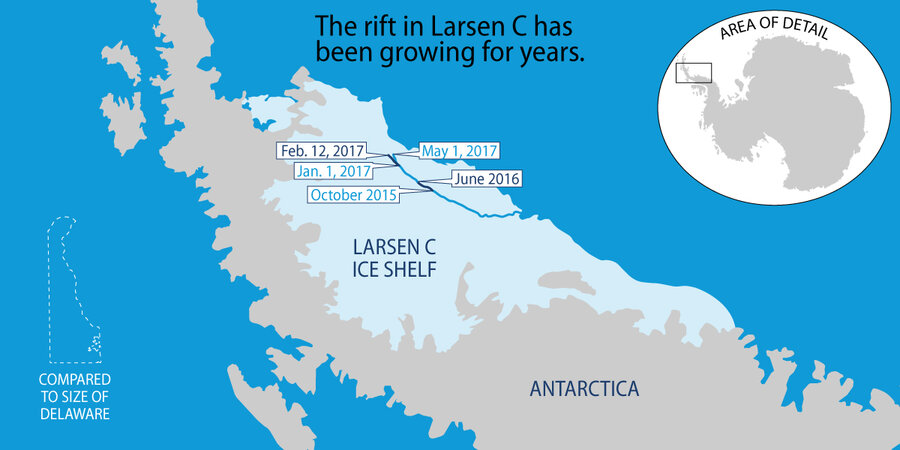

It’s been a massive polar spectacle, viewed in slow motion. Scientists have been tracking the growing rift in Antarctica’s Larsen C ice shelf for several years, and the final break has been expected for months. Sometime between Monday and Wednesday this week, the enormous iceberg – weighing more than 1 trillion tons – finally calved, fundamentally changing the landscape of the Antarctic Peninsula. The event has scientists and others riveted, and it’s a fascinating geological phenomenon to watch play out in real time. But it’s also important not to overplay its significance in the context of climate change. Unlike the disintegration of the Larsen B ice shelf, it’s unclear that human-caused climate change played a role here. And while the calved iceberg is massive, it won’t contribute to sea-level rise, since ice shelves are already floating in the ocean. Indirectly, though, ice shelf collapse can contribute to sea-level rise by allowing glaciers to flow more rapidly into the ocean. And scientists will continue to closely monitor the evolution of Larsen C for signs of any more instability.

Symbolism, significance: What ice shelf’s breakaway really means

The term “calving” might seem to imply something small, but there’s nothing small about the iceberg that just broke off from the Larsen C Ice Shelf in Antarctica.

Roughly the size of the US state of Delaware, the newly formed iceberg weighs more than a trillion tons, and its volume is twice that of Lake Erie. It’s one of the largest ever recorded.

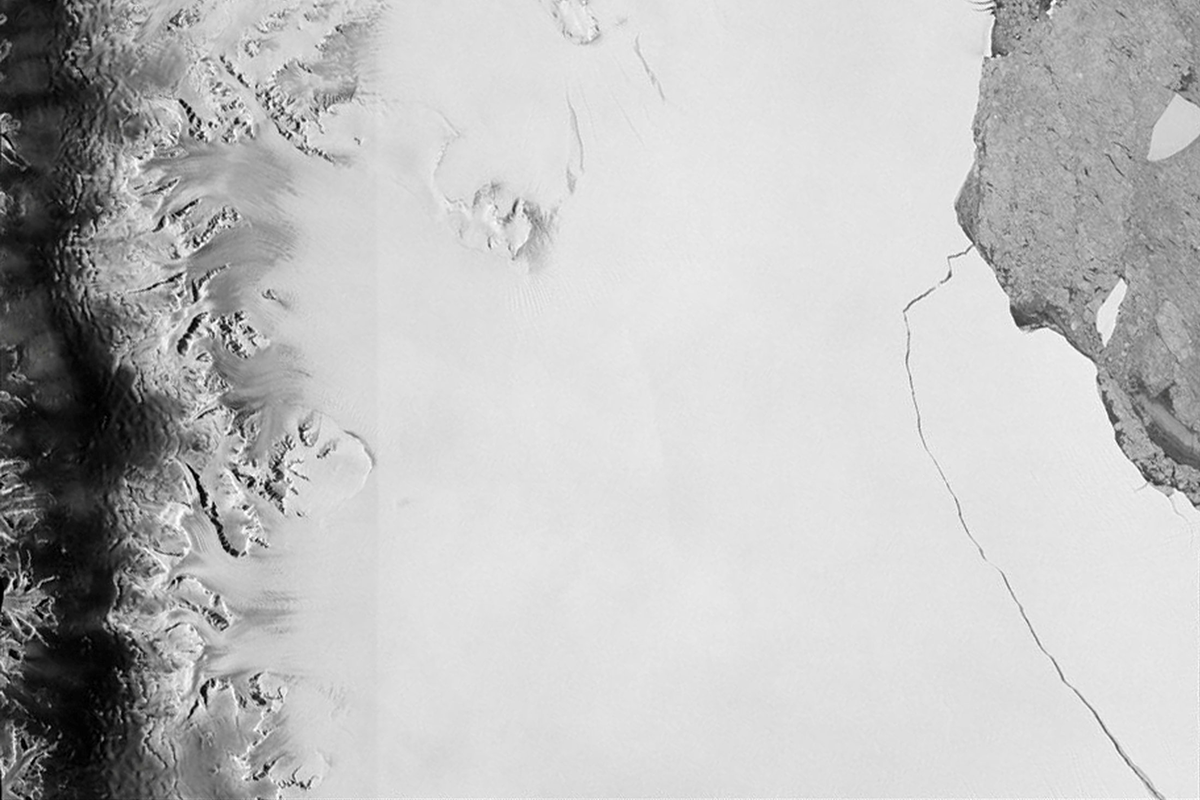

Scientists have been watching the growing rift in the Larsen C ice shelf for years now, though the exact moment that the calving finally occurred – sometime between Monday, July 10 and Wednesday, July 12 – is tricky to pinpoint.

What happened, and why does it matter?

A calving or break-off of this size is always an important event, and this one dramatically alters the landscape of the Antarctic Peninsula, leaving the huge Larsen C Ice Shelf the smallest it’s been since it was discovered in 1893.

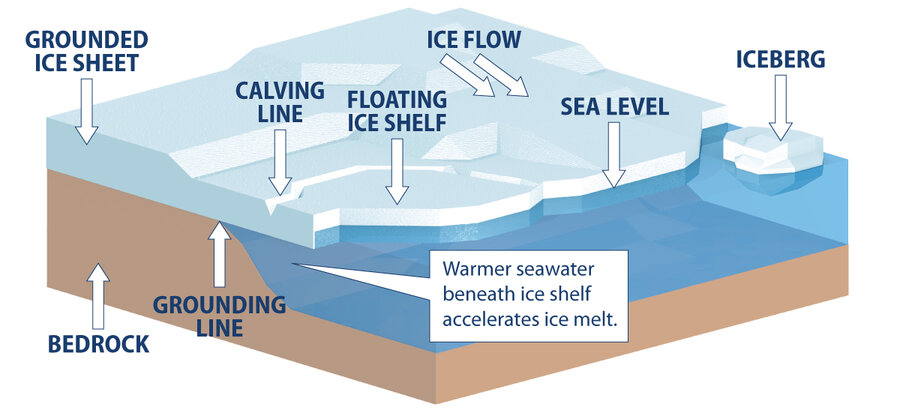

On one level, a calving like this is a natural event, part of the constant growth and reduction of ice sheets. These huge floating ice masses extend out from glaciers on land. They grow as glaciers flow into them and from snow accumulation, and they shrink from calving as well as melting at their upper and lower surfaces.

The Larsen C Ice Shelf should continue to naturally regrow, but researchers at Swansea University in Wales, who lead the MIDAS Project following Larsen C, have said that the shelf may be less stable following the rift, and that there is potential for it to follow the same path of its neighbor, the Larsen B Ice Shelf, which had a major calving event in 1995 and then disintegrated in 2002.

“In the ensuing months and years, the ice shelf could either gradually regrow, or may suffer further calving events which may eventually lead to collapse – opinions in the scientific community are divided,” said Adrian Luckman of Swansea in a blog post Wednesday. “Our models say it will be less stable, but any future collapse remains years or decades away.”

MIDAS Project, A. Luckman, Swansea University

Is climate change involved?

This is a matter of debate among scientists. Unlike some other major ice shelf rifts – including the calving and eventual disintegration of Larsen B – there’s not a clear role played by human-caused climate change.

The ice shelf had been thinning for several decades, due in part to warmer air, causing surface snow to melt, sink down into the thicker snow layer, and refreeze.

“It doesn’t seem like surface warming is causing the break,” says Ted Scambos, lead scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC).

But, he says, there was likely a small amount of thinning on the underside of the ice shelf – even though it’s in a cold-water system where temperatures are barely shifting – which could have made a critical difference.

“That few percent of ice-shelf thickness change may have been enough to make it weaker and allow it to crack in this new location we haven’t seen before,” says Dr. Scambos. “That would be a climate-change effect, though not a significant one, and nowhere near what we saw from Larsen A and B.”

Does this contribute to sea-level rise?

The short answer is no. The ice shelf was already floating, so its break doesn’t affect sea levels, in the same way that an ice cube in a glass wouldn’t change the water level even when it melts.

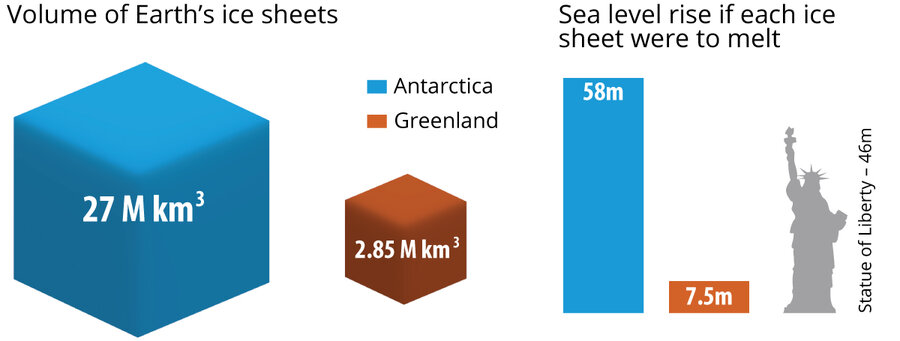

The big players in sea-level rise are the massive ice sheets (which sit on land) in Antarctica and Greenland, which together store 99 percent of the world’s freshwater ice. If those two ice sheets melted completely (not something anyone is suggesting is likely in the foreseeable future), sea levels would rise by about about 66 m (217 ft).

Indirectly, disintegration of ice shelves can contribute to sea level rise in that they provide a buffer between the ice sheets and the ocean; as they disappear, glacial flow into the ocean can increase.

In other areas of Antarctica, such as Pine Island Bay and other areas along the South Pacific coast – where no big ice shelves remain – those changes are more concerning, and more rapid, than at the Larsen Ice Shelf.

“The Larsen C is an example of where even in cold-water systems… you can eventually impact the stability of an ice shelf that looked like it was good to go for the next 30 or 40 years,” says Scambos. “The events on Larsen C might be telling us more about how large ice shelves elsewhere – like the Ross and Ronne – will evolve in the future.”

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

How does this play into the broader world of polar ice?

For the average person watching reports of decreasing Arctic sea ice, or retreating glaciers, or melting ice sheets, parsing the terms, and the changes, can be difficult.

Sea ice, for instance – the relatively ephemeral floating icebergs in both the Antarctic and Arctic that form when ocean water freezes – is much more significant in the Arctic, which lacks a continent at the pole, than in the Antarctic. That's one reason the rapidly shrinking sea ice cover in recent years has gotten so much attention.

In Antarctica, sea ice has actually been growing, but much of the research attention has been directed toward ice shelves like the Larsen C – which float in the sea, but are an extension of land ice – and the massive Antarctic Ice Sheet.

The effects of climate change on the Antarctic are much less clear than they are for the Arctic, but close satellite monitoring is helping scientists get a better handle on how changes are occurring.

With the Larsen C rift, scientists will be closely watching where the floating part goes, changes in speed, and whether any new cracks appear in the ice shelf that indicate continued instability, says Scambos. “If it really is the start of a retreat until we do see parts of the Larsen C Ice Shelf gone, maybe we can point to this event, and say it started then. Right now, there’s a better than even chance that the ice shelf will simply push back out again for at least a few years, back in the direction where the ice was lost.”

MIDAS Project, A. Luckman, Swansea University

Analysis

The other ‘Russia story’: a quiet shift inside Ukraine

As we noted in our story about the US entry into World War I, many Europeans are worried about a United States they see as drawing inward. But Ukraine got a different message from the US last weekend – one that bolsters its passion for democracy.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Pond Contributor

The controversy over Russian meddling in the 2016 US presidential election may be more visibly on the boil. But its annexing of Crimea two years earlier – and its resulting clash with Ukraine – remains more than a simmering concern. One major worry in Western countries just last week: President Trump would strike a deal with Russian President Vladimir Putin that would sacrifice Ukrainians to Moscow’s dominance in return for a vague promise of Russian restraint in, say, Syria. But this week, the pressure has shifted to Mr. Putin, who now worries that Ukrainians’ continuing enthusiasm for Western democracy and rule of law might sway his own Russian subjects. What changed? One factor, at least: a brief Sunday stopover in Ukraine by US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson in which he signaled clearly that the US is engaging more robustly with the pro-Western Kiev government. Pointedly, Mr. Tillerson met first with key reformers. That no doubt caught the Kremlin’s attention.

The other ‘Russia story’: a quiet shift inside Ukraine

Lost in all the attention focused on President Putin's presumed meddling in the 2016 US election is the changing state of Russia's ongoing undeclared war on Ukraine. But in his brief stop in Ukraine on Sunday, US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson brought it to the fore, scoring a judo flip on the Russian judo master.

The big question last week was the West's worry that President Trump might reach a strongman deal with Putin that would sacrifice Ukrainians to Moscow’s dominance in return for a vague promise of Russian restraint in, say, Syria.

But this week, the big question belongs to Putin, who now fears that Ukrainians’ continuing enthusiasm for Western democracy and rule of law might sway his own Russian subjects.

As a Newsweek headline put it, “Despite Cozy Trump-Putin Summit, Tillerson Zaps Russia, Backs Ukraine.”

In other words, Putin’s military brashness when he started his undeclared war on Ukraine in 2014 by annexing Crimea has become a vulnerability in 2017. The West, which has struggled to confront Putin’s attacks on Europe’s 70-year-old system of peace and integration, is rediscovering its own resilience. Putin, meanwhile, is rediscovering the fundamental weakness of his country's economy and politics, exposed by Ukraine's defection from centuries of East Slav fraternity with Russia.

Within Russia, jingoist pride in seizing neighboring countries' territory is losing some of its mobilizing power. Alexei Navalny’s nascent campaign to challenge Putin in the next presidential election is gaining strength, and while Mr. Navalny does not oppose Russia’s intervention in Ukraine, the growing popularity of an independent challenger to Putin would have been unthinkable during the euphoria of Crimean annexation.

Putin, an old KGB hand who doesn't understand the self-organizing power of Ukraine’s vibrant civil society, may attribute it to manipulation by Ukrainian and Western secret services. Yet he himself was the one who united Ukrainians in a historically unprecedented anti-Russian identity through his war, at a cost of more than 10,000 dead and 1.8 million Ukrainian refugees. By now, even Russian-speaking Ukrainians in the eastern part of the country (who long mistrusted western Ukrainians), are converging with their compatriots for an overall 57 percent who hold "cold" or "very cold" feelings toward Russia.

The Tillerson flip

Tillerson achieved his over-the-shoulder flip by making four points in Kiev.

First, he said Washington will not lift the financial sanctions it imposed on much-needed Western investment in Russia until Russia returns the territory they seized from Ukraine.

Second, he signaled that the US is finally bringing its muscle to the desultory Minsk peace talks on the “separatist” eastern Donbas that is in fact controlled by 5,000-10,000 rotating Russian troops. He also said that Moscow must take the first step in stopping violations of the cease-fire agreements of 2014 and 2015.

Third, Tillerson brought to Kiev Kurt Volker, his freshly minted special envoy for peace negotiations in Ukraine. Mr. Volker is a protégé of Sen. John McCain (R) of Arizona, and, like Mr. McCain, publicly endorsed delivering defensive weapons to Kiev in 2014 and campaigned against letting Putin “[call] NATO’s bluff.”

Volker won’t be calling for NATO action against Russia, but he will surely revive the debate about providing high-tech defensive weapons to Ukraine’s surprisingly robust Army.

Fourth, Tillerson is now reviving the alliance between the West’s financiers of the pro-Western regime in Kiev and the embattled young reformers in Ukraine’s parliament, media, and civil society. In the absence of existing democratic institutions, this is the only engine that might make deep enough reforms to break the business-political collusion that has not yet been rooted out in Ukraine. The reformers provide the intelligence; the West withholds money if reforms continue to be blocked. Tillerson publicly warned President Petro Poroshenko and other oligarchs that if they do not clean old judges out of the courts and guarantee rule of law, Western investors will stay away.

Pointedly, Tillerson met first with reformers, including Mustafa Nayyem, the Afghan-Ukrainian who started the Maidan demonstrations that toppled the old regime in 2013.

Tillerson’s gamble could, of course, be halted by one contrary 3 a.m. tweet from his boss. But until that happens, the secretary of State is creating a new fait accompli on the ground in Ukraine that is no doubt catching the Kremlin’s attention.

Elizabeth Pond is a former European Bureau Chief for The Christian Science Monitor.

A subject in motion: one state’s revolutionary bid to boost physics

A grasp of physics undergirded any number of developments in the 20th century – from automobiles to computers. That's why educators are scrambling to bolster the ranks of future physicists as we move through the 21st.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Charlie Wood Staff

An access-to-physics revolution is happening across New Jersey. In Trenton – one of the cities leading the charge – the focus is on training teachers and upending the way the subject is taught by allowing high school students to take the class freshman rather than senior year. As a result, more students from a variety of backgrounds are becoming well-versed in velocity and static electricity. “We’re giving every student in Trenton access to physics and chemistry, even students with disabilities,” says Michael Tofte, a science supervisor in the district, which is about 97 percent African-American and Latino. Building a foundation for future Einsteins is imperative now that physics education is in crisis. Just a third of high-schoolers take it, and 40 percent of schools don’t even offer it. That figure exceeds 50 percent when it comes to schools that are largely African-American and Latino. Only a handful of physics majors aspire to become a high school teacher. But Robert Goodman, founder of a program New Jersey is using, seeks to re-engineer that pipette-thin pipeline.

A subject in motion: one state’s revolutionary bid to boost physics

Four adults huddle around a mirror, but rather than their reflections, it’s the light beams they’re focusing on.

Their experimentation is part of an optics lab for educators, one designed to help preserve the teaching of physics, which is increasingly in jeopardy in the United States. The instructor for this session, Yuriy Zavorotniy – one of the architects of a successful science curriculum changing the face of physics education in New Jersey – hopes to solve two problems at the same time: making high school physics accessible to all students while filling a dearth of qualified teachers.

Mentoring teachers is part of an access-to-physics revolution that is happening across New Jersey. Trenton, one of the cities leading the charge, is training teachers and upending the way the subject is taught by allowing students to take it freshman rather than senior year. As a result, more students from a variety of backgrounds are becoming well-versed in velocity and static electricity.

“We’re giving every student in Trenton access to physics and chemistry, even students with disabilities,” says Michael Tofte, supervisor for K-12 science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) in the district, which is about 97 percent African-American and Latino. “It will be on their transcripts when they go to apply for colleges.... The problem-solving skills ... will be helpful in 21st-century careers.”

Helping build a foundation for future Einsteins is imperative now that physics education is in crisis. Only about 40 percent of high schoolers take it, and 40 percent of schools don’t even offer it, a figure that exceeds half when it comes to schools that are largely African-American and Latino. Just 1 in 20 physics majors harbors aspirations of becoming a high school teacher. But Robert Goodman, founder of the program Mr. Zavorotniy works with, seeks to re-engineer that pipette-thin pipeline with a batch of curriculums called the Progressive Science Initiative (PSI).

With so few physics graduates opting to pursue careers in education, the nonprofit New Jersey Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL), manager of the PSI curriculums and training program, flips the traditional career path by taking certified educators and teaching them physics.

Now in its tenth year, CTL is the nation’s largest producer of physics teachers, with an average of 27 earning credentials annually. By comparison, most university programs produce fewer than two each year, though some get into the teens. The curriculum has even spread abroad, with pilot projects in The Gambia and Argentina. (Schools must be willing to teach physics in ninth grade in order to participate, which has posed a challenge to broader implementation because it requires a shift in the typical biology-chemistry-then physics mindset.)

An intensive summer training course can get an English or math teacher into the physics classroom come fall. Coaching and weekly training classes continue throughout the year, keeping teachers a few months ahead of their students and ending with the state’s standardized certification exam to teach physics. Schools often pay for the $8,000 program, making this career-booster a win-win for both teachers and districts.

Seasoned math teacher Denise Cole, one of the pupils in Zavorotniy’s class in Teterboro, admits picking up physics was tougher than expected. This past year she studied Advanced Placement (AP) physics while teaching algebra-based physics to special-needs students, many of whom are on the autism spectrum, at the private Windsor School in Pompton Lakes, N.J.

“I’m picking up momentum and going deeper,” she says. Next year she plans to teach a special Physics 2 class so her students, who tend to learn at a slower pace, can complete the extensive coursework, which touches on ideas in particle physics that even some college curriculums don’t reach.

Closing the achievement gap

But the teacher explosion is only half of the equation. PSI’s innovative teaching methods are catapulting students to new levels of achievement.

In Trenton, for example, where only a small percentage of students meet state standards, over three-quarters of ninth-graders passed physics in 2015-16, a third with A's or B's.

In schools using PSI, African-American students were nearly 11 times more likely to participate in the Advanced Placement Physics B exam and 3.4 times more likely to pass it than African-Americans in non-PSI schools, a 2016 study found. And they are narrowing the gap between their scores and the national average among students of all races.

For Mrs. Cole’s students, the benefits extend beyond grades. “The kids are just so proud,” she says. “It’s just a builder for them as a freshman to say, ‘I took physics.’ You can see the way they light up.”

Kennisha Pressley's ninth-grade class at Trenton Central High is an example of the impact the program can have. On a recent morning, the students worked through word problems. After some strategic questioning, they figured out which formula would best calculate a vehicle’s momentum. The room was quiet until an animated discussion broke out, one student thrusting his calculator in his neighbor’s face and shaking it, as if to say “No, it’s this.”

What happened next exemplifies one of the program's pillars. One by one, the students keyed in answers on their responders, and the SMART board instantly tabulated the results.

From the student point of view, their answers are lost in the pie chart’s anonymity. But the teacher can see who's confused and when the class needs an on-the-spot review. What’s more, the technology inverts typical participation incentives. With the teacher waiting for everyone to respond, it’s not answering that attracts the spotlight.

“I don’t have to pick on them and they don’t have to say the wrong answer in front of the class,” explains Ms. Pressley.

The SMART Board and responder technology, often subsidized by Department of Education or National Education Association grants, amplifies classic educational techniques, letting teachers repeatedly poll the entire class with questions baked into the pre-made presentations that form the curriculum’s fabric. Add a pinch of working with friends, and it’s no wonder kids suddenly enjoy physics class.

The PSI system answers another long-held prayer of physics teachers: early math integration. Rather than waiting for assumed upperclassmen algebraic skills, PSI provides a first-year algebra course that delivers the tools physics classes need. The symbiosis puts to rest that dreaded math question, “When are we going to use this?” while building a foundation for future courses in biology and chemistry.

Birth of the revolution

The story of the physics revolution here traces back to Dr. Goodman’s experience with a school counselor telling him not to bother with math or science because he was no good at them. For his required science course in college, he chose physics and fell in love, later transferring to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology before going on to lead several companies.

“No one knows what they are able to do until they get exposed to it,” he says.

When he became a teacher nearly 20 years ago, Goodman landed with freshmen at Bergen County Technical High School in Teterboro, N.J., and quickly found that the pre-engineering students didn’t have the algebra base they needed. To help, he designed a math-heavy physics curriculum, and it became so popular that within a few years all the freshmen were taking the course.

People started to take notice after Bergen Tech rocketed to the top of the AP Physics rankings, and CTL was born. Now the state enjoys nearly twice as many physics teachers, enabling otherwise-struggling districts like Trenton to offer the subject.

Trenton, with about 2,400 high school students, now has 20 teachers certified to teach physics. All but one or two came through CTL training, and they are a diverse group – racially, linguistically, and by gender.

Less planning, more responsibility

Teachers appreciate how the program’s pre-packaged activities – including homework, evaluations, and hands-on labs – shift the burden of work from planning to actual teaching. But the course still isn’t entirely plug-and-play. Using teacher talent to add “juicy details” is essential, says Adam Behr, who teaches AP Physics at Trenton High. “If you just run through the slides ... it’s dry, and the kids will fight you on it pretty hard.”

Whether it’s those wonder-sparking asides, the responders, or the early introduction to a traditionally advanced subject, something’s working wonders in New Jersey classrooms. Despite freshmen coming in “already turned off to science,” by the end of their second year Mr. Behr says at least a few students will likely earn college credit via high AP scores.

For Trenton High sophomore Max Elias, who once got low science grades, PSI has been transformative. “I like the way [physics] tries to explain how everything exactly works,” he says. “In a way, it’s beautiful.”

Editor's Note: This article has been updated to reflect more recent physics class enrollment data. About 40 percent of high school students took physics during the 2012-2013 school year.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Amid the rubble of Mosul, Iraqi reconciliation

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By Monitor's Editorial Board

For all of its problems, Iraq – which just reclaimed the city of Mosul – has shown an improved focus on national reconciliation after three years of witnessing the alternative: mass slaughter and undemocratic governance in Islamic State-run areas. At the height of its power, ISIS controlled 40 percent of Iraqi territory and some 10 million people. Now it is on the run in the face of Iraq’s renewed sense of national identity. Every country emerging from violent conflict has to find a path to reconciliation. Sometimes the need is for forgiveness, justice for victims, or land restitution. For Iraqis, the need is to build on its successes since 2015 in overcoming religious divides in politics, curbing corruption, and creating the kind of trust that allows for differences and the rights and freedoms for minorities. Iraq may have finally learned that it cannot afford to ignore its minorities or leave a political vacuum.

Amid the rubble of Mosul, Iraqi reconciliation

When the Islamic State (ISIS) took over Iraq’s second-largest city in 2014, one of its first acts was to kill any Mosul resident who merely thought differently. Now compare that murder spree on individual conscience to what has happened since Iraqi forces recaptured the city on July 9.

Civilians are returning, not fleeing or being killed – and they are speaking their mind. Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi promises to create stability for Mosul and extend the political unity among Iraqi leaders in fighting ISIS. Foreign donors have offered reconstruction aid for the city. On July 15, leaders of the country’s minority Sunnis will meet to discuss ways to reconcile with the majority Shiites. And with Mosul’s liberation, more Iraqis are eager for elections in September.

For all its problems – including the need to suppress remaining ISIS insurgents in smaller cities – Iraq has shown an improved focus on national reconciliation after three years of witnessing the alternative of mass slaughter and undemocratic governance in ISIS-run areas. At its height of power, ISIS controlled 40 percent of Iraqi territory and some 10 million people. Now it is on the run in the face of Iraq’s renewed sense of national identity.

Every country emerging from violent conflict has to find a path to reconciliation. Sometimes the need is for forgiveness, justice for victims, or simply land restitution. For Iraqis, the need is to build on its successes since 2015 in overcoming religious divides in politics, curbing corruption, and creating the kind of trust that allows for differences and the rights and freedoms for minorities.

Sunni parliamentary speaker Saleem al-Jubouri has called on the government to adopt a “well-defined approach to social justice.” Mr. Abadi admits that corruption is as harmful as terrorist groups or sectarian distrust. And almost every Iraqi leader speaks of reducing foreign influence, especially by Iran in its support of Shiite militias.

The most remarkable restoration of unity has been in the Iraqi security forces since their defeat by ISIS three years ago. More officers are being promoted by merit than political affiliation. And even though Shiites dominated Iraqi forces, they have generally treated Sunnis well in liberated areas.

Iraq may have finally learned that it cannot afford to ignore its minorities or leave a political vacuum. ISIS, like Al Qaeda before it, was adept at playing on Sunni grievances. While military action was needed to retake Mosul, what is needed even more is the rebuilding and reintegrating of Iraq. In a word, reconciliation.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Is truth dead?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Rosalie E. Dunbar

More than 100 years ago, Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy observed, “The question, ‘What is Truth,’ convulses the world” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 223). We might say the same is true today. For contributor Rosalie E. Dunbar, a deeper understanding of Truth as God helped her to support healing and resolution when wrongdoing was uncovered in her local government. “Real truth,” she writes, “expresses God’s goodness, lawfulness, and love. Whatever divides, darkens, or confuses – such as hatred or violence – is not part of or justified by Truth.” Prayer from this basis is a reforming influence.

Is truth dead?

“The question, ‘What is Truth,’ convulses the world,” wrote Mary Baker Eddy, who founded the Monitor and was an astute observer of the world (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 223). The turmoil in many parts of the globe today certainly illustrates that point.

Sometimes efforts are made to obscure the truth, as in fake news. Being able to discern the accuracy of what we read – to separate fact from fiction – is important. And I’ve found help in Christian Science, which gives a deeper understanding of God as divine Truth. What we might call “real truth” expresses God’s goodness, lawfulness, and love. Whatever divides, darkens, or confuses – such as hatred or violence – is not part of or justified by Truth. God, who is also Love, cannot and would not instill in anyone’s heart anything opposite to Love’s own nature.

The longing of the human heart to know what’s true is perennial, and is a thread woven throughout the Bible. Christ Jesus’ understanding of divine Truth not only enabled him to demonstrate the truth of God’s power to heal sick people, but also made him fearless in dealing with pride and corruption. In the face of his wholly unjust crucifixion, Jesus declared to the official sentencing him: “To this end was I born, and for this cause came I into the world, that I should bear witness unto the truth. Every one that is of the truth heareth my voice” (John 18:37). And he proved the profoundness of the spiritual truth to which he was witnessing in powerful acts of reformation and healing.

As I better understand the spiritual truth behind Jesus’ life and teachings, it has had an impact in my life. I can more readily discern between what is of Truth and what isn’t, and begin to see healing results in more modest occasions of facing corruption.

One time a group of town employees was engaged in wrongdoing that had an impact on my community as well as a neighboring one. When this came to light, I began praying.

My prayers helped me recognize at least two things. First, that each individual involved was in reality the spiritual creation of God, Truth, and therefore honesty was natural to everyone. I’ve found that cherishing this inherent honesty in people is a spiritual influence that subdues wrongdoing and dishonesty. It paves the way for reform where needed. Second, I saw that the desire to do the right thing is empowered by divine help.

Soon significant changes were made to improve the department that had been involved. Also, an arrangement was worked out so the situation could be peaceably resolved with the neighboring community.

I know I wasn’t the only one praying and working to resolve this situation, but I trust this prayer contributed to decisions that led us back on course – because I have seen, over the years, how God can guide us out of any trouble.

Divine Truth is ever present for you and me and everyone to turn to, no matter what country we are in or how dark or confusing a situation may seem. As Science and Health explains: “The inaudible voice of Truth is, to the human mind, ‘as when a lion roareth.’ It is heard in the desert and in dark places of fear” (p. 559).

This spiritual fact can inspire our prayers for our families, communities, countries, and the world.

A message of love

Defiance

A look ahead

That's a wrap for today. Tomorrow, we'll consider this question: Can newly minted Millennial teachers envision working in an area without fitness clubs and Thai restaurants? The next generation's future may lie in the answer.