- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- A year after failed coup, Turkish opposition still tries to regroup

- As a campus-culture battle flares, alliances find common ground

- Why long-held lines on jobs and gender are fading away

- Foreign correspondents channel global interest in ‘Trump show’

- Ravens offer new clues about how animal intelligence evolved

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for July 14, 2017

Today at the Capitol, a couple of lawmakers are playing outsize roles in the debate over health-care legislation that will profoundly affect millions of lives. In Paris, a couple of presidents met.

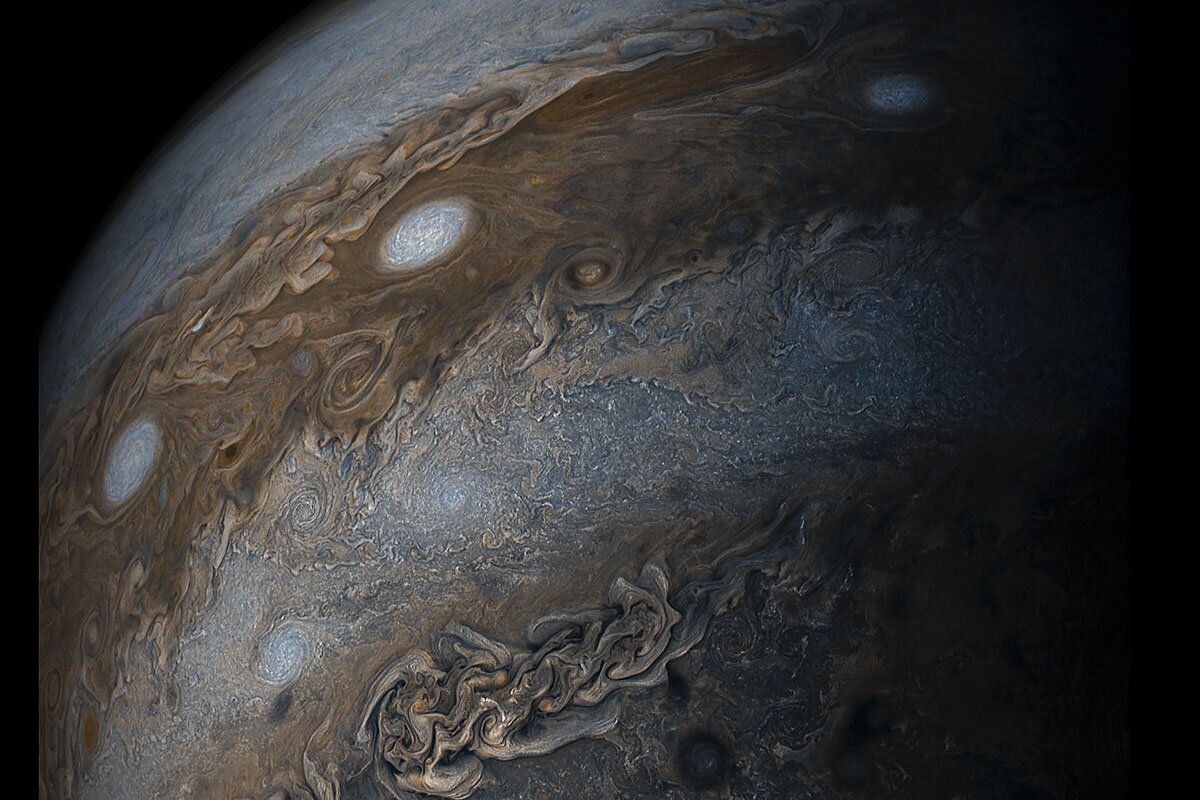

Zoom out. Way out. Let’s go off-world.

An interesting sub-story around the newsmaking flight of the Juno spacecraft – now delivering spectacular views from above gaseous Jupiter’s cloud deck – is the outsize role of ordinary people.

The scientific stakes are high. Humanity last took a close look at Jupiter a generation ago (Galileo). Before that, fully two generations ago (Voyager). This time around, a relatively low-budget device called the JunoCam – added to the mission simply for “public outreach” – is being directed by telescope-armed citizen scientists suggesting points of interest to observe, and then helping to process the images that Juno beams home in a way that, as Scientific American reports, “leaves professionals spellbound.” (To judge for yourself, check out our Viewfinder gallery below.)

“[T]he overarching takeaway from these new images,” a planetary scientist tells the magazine, “is how relatively blinkered most of our earlier views have been.” Power, in part, to the people.

Now to our five stories for today.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A year after failed coup, Turkish opposition still tries to regroup

In Turkey, a long-running "strongman" saga in a strategic corner of the world is really becoming a case study in how opposition seldom works without unity, reports Scott Peterson from Istanbul.

This weekend Turkey is marking the anniversary of last summer’s failed coup, in which, it says, 246 “martyrs” died “defending democracy.” For critics of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, however, it was an event he exploited to fortify his own power. The ensuing state of emergency brought wide-scale arrests and the purge of 140,000 teachers, soldiers, police officers, judges, and others. That crackdown was a harsh blow for Turkey’s opposition. But this week, to culminate a 25-day, 280-mile march, tens of thousands of Turks gathered in Istanbul to protest Mr. Erdoğan’s authoritarian rule and to call for justice. It was an emotional show of strength after a string of losses, most recently the opposition’s failure to block a referendum this spring that expanded the powers of the president. But experts caution it is too soon for Erdoğan’s foes to build dramatically on this “huge act of courage and defiance.” The president’s foes are “united in their opposition to authoritarianism, but not in a common vision for Turkey,” says one expert, adding that a charismatic figure is still needed to unify disparate factions.

A year after failed coup, Turkish opposition still tries to regroup

The crowd stretched for as far as the eye could see: the biggest flag-waving Turkish opposition rally in many years.

They were Turks angry at the authoritarian rule of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan; Turks joyful that their call for “justice” may be heard; Turks hopeful that the promises of opposition unity may be real.

The mass rally on July 9 marked the culmination of a 25-day, 280-mile opposition march from the capital, Ankara, to Istanbul that attracted tens of thousands of citizens. They flocked to the opposition’s banners despite being pilloried as akin to “terrorists” and dangerous provocateurs by Mr. Erdoğan and the Islamist ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP).

Yet, as emotional as the mass event was, it is still far from clear whether the political spectacle will inspire a credible resurgence of Turkey’s fractured opposition.

This weekend marks the anniversary of last summer’s failed coup, which Erdoğan’s critics say he has exploited to fortify his own power and crack down on a range of political opponents. Speaking Thursday, the president highlighted the “epic dimension” of the coup attempt, saying Turkey learned in those dramatic hours “that we will either die or exist,” and declaring: “We are leaving a very important legacy to future generations."

The anniversary is also a poignant reminder that the opposition has been on a long losing streak, including, most recently and significantly, its failure this spring to block Erdoğan from narrowly winning a referendum granting him expanded, near-unassailable presidential powers.

“While [the rally] is undoubtedly a huge act of courage and defiance, I want to caution against seeing this as a major game changer,” says Aslı Aydıntaşbaş, a senior fellow with the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) in Istanbul.

“The 50 percent is united on anti-Erdoğan sentiment, and united in their opposition to authoritarianism, but not in a common vision for Turkey,” says Ms. Aydıntaşbaş. The opposition task “is to use the hope and energy” created by the march and rally to lay out a plan to unify disparate factions.

Notably missing, she says, is a charismatic figure who can unite the opposition.

“Turkey needs a Turkish Macron, and it’s not out there yet,” says Aydıntaşbaş, referring to French President Emmanuel Macron, who despite being a political unknown a year ago, recently upset a crowded field of seasoned candidates. “This was a good step, but I haven’t got the feeling there is a day-after scenario yet.”

Anniversary of coup

The opposition show of strength comes as Erdoğan and the AKP are preparing elaborate ceremonies to mark the July 15 anniversary of the attempted coup as a day when 246 Turkish “martyrs” died, they say, “defending democracy.”

But that event also yielded a continuing state of emergency, a fierce crackdown on civil society, the arrests of 50,000 people, a purge of 140,000 teachers, soldiers, police, judges, and others, and a tighter grip by Erdoğan – all reasons such a broad spectrum of Turks took to the streets for the opposition march and rally.

The march was led by Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the leader of the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP), in the first sign of opposition life since the April referendum.

“The final day of the ‘justice march’ is a new beginning and a new step,” Mr. Kılıçdaroğlu boomed from the stage at the sea of supporters, who chanted “Rights, law, justice!”

“It’s not the end of a march…. It’s a new climate, a new history, a new birth,” he said. “We marched because we are against a one-man regime [and] because we are against terrorist organizations and because of the fact that the judiciary has been taken under the orders of politics.”

“Erdoğan is a dictator!” said one rally-goer amid the crowd, sweating under the hot summer sun, a white headband with the Turkish word for justice, adalet, across his forehead. Others were far less charitable about the man who has ruled Turkey with an increasingly tight grip since 2002.

Obstacles to opposition unity

But analysts say despite the unexpectedly popular stratagem of the march, there are immense obstacles to converting that rejuvenated energy into unity between the CHP, nationalists, and the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP). In an election two years ago, in a rare electoral setback for Erdoğan, the HDP exceeded for the first time the 10 percent threshold for representation in parliament. The party has been under especially sustained attack, with arrests of its leaders and lawmakers on terrorism charges, since fighting between the Turkish state and Kurdish militants reignited in southeast Turkey in July 2015.

The HDP called on its supporters to join the rally for “social justice,” to “be in the field with all our power, to deepen the crack in the fascist-chauvinist bloc.”

Critics charge that Erdoğan and the AKP have used the coup, and the tools of the state of emergency, to consolidate their own power by jailing opponents and journalists and restricting opposition parties.

Kılıçdaroğlu derides the state of emergency as a second – successful – coup against the Turkish people.

Criticizing the march this week, Erdoğan invoked Muslim piety: “They could walk 450 kilometers for the terrorists, but could not take 4-1/2 minutes to read a fatiha [Quranic prayer] for the [July 15] martyrs?”

Erdoğan noted the demand of marchers to end the state of emergency, which has been extended repeatedly: “This job will end when it’s completely over,” he said.

Doubts about opposition

The scale of the march “was a key moment, but I think that one should be very realistic regarding what the opposition is capable of achieving in Turkey, because contrary to all the rhetoric, there is no opposition front in Turkey – it doesn’t exist,” says Cengiz Aktar, a senior scholar with the Istanbul Policy Center at Sabanci University.

“Will the opposition manage to gather its forces, especially including the Kurds? I have very serious doubts,” says Mr. Aktar. CHP voters “are historically anti-Kurdish, and it will take them another decade probably to understand that without due attention paid to the Kurdish issue there won’t be a political alternative to Mr. Erdoğan and the AKP.”

In a bid to broaden the appeal of the march and rally, CHP leaders ordered that only non-party banners be flown, include the national flag, the “justice” motto of the event, and portraits depicting the secular founder of modern Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

“Maybe the best outcome of this ‘justice’ march was that people, after one year, are today more concerned about the consequences of the so-called coup, rather than the coup itself,” says Aktar. “People realize more and more it was a big, big game and the entire country is paying the price.”

'Not the same Turkey'

The CHP joined the AKP after the coup attempt in a sign of national unity, and supported national solidarity rallies that lasted across the country for a month. But the march began mid-June, the day after one senior CHP official was sentenced to 25 years in prison for leaking information to the media about the Turkish state providing weapons to Islamists fighting in Syria.

The fact it was led day after day in sweltering temperatures by the 68-year-old CHP chief, accused in the past of uninspired and ineffective leadership, “showed that nothing is impossible,” wrote columnist Semih İdiz in the Hürriyet Daily News.

“No one is expecting an overnight miracle to emerge from this march, [but] we are not the same Turkey as we were before it took place,” wrote Mr. İdiz. “Erdoğan and the AKP are no doubt sleeping a little less comfortably now, with presidential and parliamentary elections not so far away in 2019.”

Fractures in the opposition aside, the intense official reaction may meanwhile have as much to do with dissent within AKP’s own ranks, says Aydıntaşbaş from ECFR.

“This is what the AKP leadership fears the most, not so much what happens with the opposition, but what happens with their own constituents, the internal grumbling, the quiet resentment about what AKP has come to symbolize,” she says.

“This may not come out publicly, but in quiet corners of AKP, people are complaining, saying, ‘This is not what we set out for 14 years ago. We are jeopardizing our gains by becoming too authoritarian,’ ” Aydıntaşbaş says.

Share this article

Link copied.

As a campus-culture battle flares, alliances find common ground

Battle lines were renewed this week over such hot-button Title IX-related issues as the definition of campus rape. But as Stacy Teicher Khadaroo reports, the conversation left out some important work, with momentum that transcends federal politics.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

On Thursday, various groups with a stake in the enforcement of Title IX had the ear of Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos during three listening sessions featuring personal stories on various facets of the issue. “What we really got from it was that she was hearing what we were saying,” says Chardonnay Madkins, project manager of the survivors’ rights group End Rape on Campus. She and other advocates worry that some protections will be rolled back under the Trump administration. But that would be unlikely to put the brakes on progress toward changing the culture and reducing sexual assault among young people. While headlines emphasize the warring sides, behind the scenes, there’s a vast array of people willing to work together – often across partisan lines and professional silos – to help colleges address this complex problem that doesn’t start or end at their gates. At the state level, that’s already yielded at least 27 laws on campus sexual assault since the start of 2015, according to the Education Commission of the States.

As a campus-culture battle flares, alliances find common ground

Sexual assault survivors have been trying to get a meeting with Betsy DeVos since she was confirmed as Education Secretary. Thursday, they got their wish – but with a catch: The secretary would be spending equal time with men’s rights groups who believe the issue is overblown or that too many innocent people have had their rights trampled.

It’s been a difficult six months for those trying to defend strong enforcement of Title IX – the civil rights law that, for this generation, has become synonymous with addressing sexual harassment and violence.

Consider: The Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights has rescinded guidance on transgender rights in schools, and it has stepped back from systemic investigations of Title IX violations on campuses, it says to reduce backlogs. If Congress cuts the Education budget, as proposed, it would mean fewer people to investigate allegations. And a public list of schools under investigation for violating Title IX, set up during the Obama administration, may be discontinued.

Campus lawyers and groups that represent falsely accused students, on the other hand, have been relieved to gain more seats at the table as Ms. DeVos considers possible changes to how the law will be enforced.

Headlines, especially this week, tend to emphasize the warring sides. But underneath that narrative, there’s a vast array of people willing to work together – often across partisan lines and professional silos – to help colleges address a complex problem that doesn’t start or end at their gates. And even if some protections are rolled back under the Trump administration, experts say, that would be unlikely to put the brakes on progress toward changing the culture and reducing sexual assault among young people.

At the state level, that's already yielded at least 27 laws on campus sexual assault since the start of 2015, according to the Education Commission of the States. “We’re seeing legislation … in blue, purple, and red states alike. Equal educational access and ending violence against women is not a partisan issue,” says Sejal Singh, a policy and advocacy coordinator for Know Your IX.

And many campuses are motivated to go beyond compliance as they see not only students, but even athletic coaches, demanding it.

“A lot of institutions have internalized Title IX to the point that, even if the federal government pulls a foot off the gas pedal, there’s a feeling that strong intervention is going to be necessary,” says Peter Lake, a Title IX expert and leader of the Center for Excellence in Higher Education Law and Policy at Stetson University College of Law. “There's a tremendous undercurrent of energy and support of combating discrimination on campus.”

“If there is a crosscurrent ... it’s due process,” he adds, referring to the way allegations of sexual misconduct cases are resolved. “That’s probably what will emerge most clearly from this period – let’s not forget about respondents’ rights.” The Education Department's OCR did address due process during Obama’s tenure as well, he says, but the issue has been gaining steam.

Seeking consensus on what’s fair

When Cynthia Garrett joined an American Bar Association (ABA) task force to recommend how colleges can ensure due process, she was sure she wanted a change in the standard of evidence that colleges are expected to apply. But her perspective shifted.

Under OCR’s landmark 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter clarifying how schools should implement Title IX, they were told to use a “preponderance of the evidence” standard. In other words, that means an official or disciplinary body needs to be just over 50 percent sure an incident occurred.

It’s a typical standard in civil rights cases, and any higher bar of proof would tilt the advantage toward the accused, survivor advocates say. Many colleges were already using the preponderance standard, but some groups have objected strongly.

Ms. Garrett is the San Diego-based co-president of Families Advocating for Campus Equality, a network founded by parents whose children were deeply affected by what they characterize as false accusations and unfair procedures.

On the ABA task force, she worked with campus administrators, victims’ rights advocates, and other attorneys. “The most amazing part is that we were able to come up with a consensus of recommendations for due process,” she says.

Garrett found her stance on the evidence standard softening. “Because we included so many other due process provisions … I became more comfortable with it,” she says.

She shared the task force’s report with Candice Jackson, the Education Department's acting assistant secretary for civil rights. Garrett spoke to the Monitor before appearing on one of the Thursday roundtables alongside representatives of Stop Abusive and Violent Environments (SAVE) and the National Coalition for Men.

Survivors’ rights advocates say such groups perpetuate the notion that women routinely make false rape accusations (something research has shown is rare) or report people simply because the regret a drunken hookup. Acting Assistant Secretary Jackson added to that narrative with a remark suggesting such cases were prevalent, in a New York Times interview Wednesday, for which she later apologized. She also noted that she herself is a rape survivor.

It’s possible that new guidance will supplant the 2011 "Dear Colleague" letter. After Thursday’s meeting, DeVos told reporters that the current policy “has not worked in too many ways and too many places, and we need to get it right.”

While survivors' advocates are anticipating rollbacks, some say they were at least encouraged to be part of the dialogue. “What we really got from it was that she was hearing what we were saying,” and that she would continue to listen, says Chardonnay Madkins, who attended as project manager of the survivors’ rights group End Rape on Campus (EROC).

States step in with more legislation

In the meantime, campus activists are doubling down on efforts to create state laws.

So far in 2017, 15 states have considered legislation, with nine laws passed and 24 pending.

One new law in Texas assures students they can report sexual assault without fear of punishment for infractions such as underage drinking.

A 2015 Illinois law required comprehensive plans from colleges and included Title IX type provisions, “so all survivors have those rights protected no matter what happens federally,” says EROC managing director Jess Davidson.

As a student, Ms. Singh says she worked to change policies at Columbia University in New York that discouraged rape survivors, such as allowing campus officials with conflicts of interests – deans who could take donations, for instance – to decide appeals.

When she and others around the state didn’t see enough response from administrators, they took the fight to the legislature.

The resulting New York law passed in 2015, the year Singh graduated. It “required my school to make changes we’ve been demanding for a long time.”

Getting at root causes

In some cases, a wide range of stakeholders are asking legislatures to slow down rather than pass misinformed laws.

New Jersey lawmakers were considering a number of related bills, including one that would have required all campus sexual assault reports to automatically trigger law-enforcement involvement.

That drew criticism from the New Jersey Coalition Against Sexual Assault, on the grounds that it’s important for victims to be able to choose when and how they report, and what remedies to pursue. The coalition helped persuade the legislature to set up a diverse task force to take a more holistic look at solutions.

Its report came out in June, and is starting to get attention from other states.

In addition to agreeing there should be no mandate of law enforcement involvement, the report addressed some lawmakers’ impulse to push for "dry" campuses, showing that there’s no research proving that prohibiting alcohol would reduce rates of sexual violence.

“Alcohol doesn’t rape,” says Patricia Teffenhart, executive director of the coalition and co-chair of the task force. “Sexual violence is caused by learned behaviors and unacceptable attitudes…. We need to get at the root of what makes someone thinks that’s acceptable.”

On a growing number of campuses, students expect administrators to face sexual violence head on.

“Regardless of what might be happening politically at OCR … our students are very committed to this issue,” says Felicia McGinty, vice chancellor for student affairs at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J., which shared some of its successful policies with the task force. “This is not about compliance. This is about commitment.”

Why long-held lines on jobs and gender are fading away

While 95 percent of firefighters are men, nearly a third of new firefighters hired since 2009 have been women. Will equal access to career paths – and a broadening shift in thought on career associations – lead toward equal pay?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Across the US economy, many occupations are still inhabited primarily by men. Others by women. But it looks as though the lines are blurring. A new study released by the website CareerBuilder, drawing on government data, finds that since 2009, women have made inroads in many fields dominated by men. And vice versa. In some cases, the changes are dramatic. Only 5 percent of firefighters are women, yet nearly a third of new firefighters hired since 2009 have been women. But smaller shifts are significant too: more female CEOs and chemists, more male elementary school teachers and cooks. One big upshot is the promise of greater pay equity for women – since academic research finds that half the gender pay gap stems from occupational or industry differences among men and women. Why are the career lines blurring? A range of reasons, but one is simple “me too” psychology. Rosemary Haefner of CareerBuilder puts it this way: “It’s, ‘I know someone who does this [job] who is similar to me.’ That might be causing some acceleration there.”

Why long-held lines on jobs and gender are fading away

Men and women tend to choose different career paths, and researchers have identified this as the biggest reason men make more money. So if men and women were equally represented across all occupations, would it close that gender pay gap?

Teaching is just one example of an occupation segregated along gender lines. Growing up in the 1990s, I didn’t have a male teacher until the seventh grade. Data suggest that’s still a typical experience: According to the Labor Department, about 80 percent of elementary- and middle-school teachers are women.

A wide array of other jobs in the United States are overwhelmingly done by one gender or the other – from low-wage cafeteria workers (61 percent women) all the way up to the C-suite (75 percent of chief executives are men).

But according to a study released July 13 by the job-search site CareerBuilder, that could be changing. Women are entering traditionally male-dominated jobs in greater numbers, and vice versa. One of the more dramatic examples: A full 95 percent of firefighters are men, but nearly a third of new firefighters hired since 2009 have been women, according to the study. On the other side of the coin, just 20 percent of elementary school teachers are men, yet men make up nearly half of all new hires in the field over the past eight years.

The softening of those gendered barriers, and evolving perceptions of which jobs are appropriate for whom, is a product of fundamental changes in the US economy, and, if the trend continues, could inch women closer to equal pay with their male counterparts.

But it’s not a silver bullet. The pay gap is a multifaceted problem without a clean fix – men still out-earn women even within the same occupations, and a dearth of women at the top of the career ladder persists.

“We could have perfect gender parity and still have a pay gap, but it’s still good news,” says Emily Liner, an economist and senior policy advisor for Third Way, a moderate economics think-tank.

To compile the report, CareerBuilder’s research arm, Emsi, drew from Labor Department and state or local sources to find male- or female-dominated occupations, and then to look at the gender ratio of new hiring in those jobs between 2009 and 2017.

Gender parity hasn’t improved markedly for every career, but the study finds that women have made inroads in the past eight years in occupations including CEOs, lawyers, web developers, dentists, sales managers, marketing managers, chemists, and financial analysts. There’s even been a big increase in women hired as sports coaches and scouts.

Some of these shifts for men and women are borne out elsewhere. According to the US Census Bureau, the number of men in nursing careers, while still small, has tripled since the 1970s.

A number of factors could be driving that migration. For men, Ms. Liner says, the evolution into a service economy is altering perceptions of what is acceptable work. “Automation and globalization are the reasons men are considering jobs they may not have before,” she says. “Manufacturing jobs, those lost to off-shoring, they tend to be male-dominated. But every community has a elementary school, every community has a hospital. So there is place-based work available to them.”

For both men and women, seeing peers take those less conventional career paths can get the ball rolling toward gender parity even faster, says Rosemary Haefner, CareerBuilder’s chief human resources officer. “It’s, ‘I know someone who does this [job] who is similar to me.’ That might be causing some acceleration there.”

In terms of increasing the 80 cents a woman earns for every dollar a man does, easing the job market’s gender segregation could play a big role. According to a 2016 paper from Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn from Cornell University, occupational differences – sales managers versus telemarketers, for example – account for 33 percent of the gender pay gap. Men and women working in different industries accounts for another 18 percent. Liner, in her research on how gender is linked to salaries, found that jobs that account for the top 10 percent of earnings in the US are almost entirely male-dominated. In contrast, women occupy over two-thirds of the lowest-wage jobs that the Labor Department tracks – entry-level retail and food service positions.

Even within those low-wage categories, there are often stark gender divides. Parking lot attendants, for example, are overwhelmingly male, and they make about $3,000 more per year on average than cashiers, who skew female. “Another one is cleaners of vehicles and equipment,” Liner says. “They’re mostly male and get paid better than maids and housekeepers.”

Historically, too, just the influx of women or men into certain careers has influenced their prestige and earning potential. Computer programming started out as unglamorous work done primarily by women, but became better-paying and respected as men became the majority. The reverse is true for a number of jobs now occupied primarily by women.

But not all of them. Pharmacists make up an occupational group that has both increased the number of women in its ranks over the long term and retained high earnings. Pharmacy is the second-highest-paying profession in the US, and has a smaller pay gap than other prestigious fields, including business and law. In a 2014 speech, Harvard labor economist Claudia Goldin credited the job’s flexibility, made possible by technology and the standardization of the work itself, as a major factor in its ability to recruit women and retain them even as they start families.

Foreign correspondents channel global interest in ‘Trump show’

It’s not that they've reduced coverage of US politics to the level of "spectacle." But journalists from around the world – and their audiences back home – are finding the current US administration to be a depiction of "American" in high relief.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Sean Spicer, Steve Bannon, Stephen Miller – all are players in the palace intrigue of the Trump White House. And they’re household names ... in China. Chinese people are “interested in everything – your entertainment, your politics, how your system functions,” says Ching-Yi Chang, White House correspondent for Shanghai Media Group. They “very much enjoy ‘House of Cards,’ ” he adds, by way of explanation. Like France’s Alexis de Tocqueville, international observers have long found America fascinating to study and explore. Foreign correspondents covering the White House call it the story of a lifetime – with profound implications for their countries. They marvel at Americans’ abiding patriotism as they salute the flag, sing the national anthem at ballgames, and thank military veterans for their service. They go to Detroit, read J.D. Vance’s “Hillbilly Elegy,” visit the Trump hotel in Las Vegas, and cram into the daily White House briefings – where only one gets a seat, and the rest stand cheek by jowl. Though some have misgivings about America’s direction, they see much good, too. “I still believe in the American dream,” says one.

Foreign correspondents channel global interest in ‘Trump show’

Sean Spicer, Steve Bannon, Stephen Miller – all are players in the palace intrigue known as the Trump White House. And they’re all household names ... in China.

Chinese TV viewers can’t get enough of the “Trump Show,” and coverage of America in general, says Ching-Yi Chang, White House correspondent for Shanghai Media Group.

“They’re interested in everything – your entertainment, your politics, how your system functions,” Mr. Chang says. Chinese people “very much enjoy ‘House of Cards,’ ” he adds, by way of explanation.

But if any parallels between the Netflix drama and real life are a bit overdrawn – even in a week of stark revelations in the Trump-Russia saga – there’s no doubt that the Trump presidency has gripped the imagination of a global audience.

And as with their American counterparts, foreign correspondents who cover the White House call it the story of a lifetime – profound in its implications for their home countries, and a fascinating window into the experiment called American democracy.

In the footsteps of de Tocqueville

The story isn’t just about a flamboyant businessman who improbably winds up in the White House, and sends a legion of investigative reporters into high gear, however. It’s also about the small towns and cultural diversity of a vast nation.

Like France’s Alexis de Tocqueville and Ilf and Petrov of the old Soviet Union, international observers have long found America an endlessly fascinating subject for study and exploration. When Akiyoshi Mitsuzawa, a reporter for the Japanese newspaper Seikyo Shimbun, came to the US recently on a two-week reporting trip, he spent only a day in Washington and more time in the middle of the country.

Probe more deeply, and members of the foreign press corps in Washington marvel at Americans’ abiding sense of patriotism as they salute the flag, sing the national anthem at ballgames, and thank military veterans for their service.

Branka Slavica, US correspondent for Croatian TV, says her countrymen are impressed that, after 241 years, America “still celebrates its birthday in such a beautiful way.” She went to the National Mall on July 4 to interview Americans who had come from all over the country to watch the parade and the fireworks.

“People were really, honestly excited about the Fourth of July,” says Ms. Slavica, who has been based in the US for 12 years. “They are every year. It doesn’t matter who is the president.”

Among the foreign correspondents based in Washington, many escape the capital when they can – out of their own curiosity and their bosses’ desire for coverage that captures the richness of America.

“We try to look at the world and America from a bit more of a helicopter perspective” than the beat reporters in Washington, says Jorgen Ullerup, US correspondent for the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten. “We go to a lot of places where people are crazy about Trump.”

Mr. Ullerup and his wife just spent a week in Kentucky looking into the opioid epidemic. Ullerup has also spent time with a fundamentalist snake handler in Tennessee, and visited the Nevada ranch of the rebellious Cliven Bundy (who, Ullerup discovered, has Danish ancestry).

'It always comes back to Trump'

But Trump is like a magnet, says Ullerup. “I travel the country to do other stories, but somehow it always comes back to Trump.”

“Today I did a correspondent’s letter about staying at the Trump hotel in Las Vegas,” he explains. “I’ve done a whole lot of Russia stories. Yesterday I wrote about the GOP and health care... The other day I wrote about Spicer.”

Not that he much minds. President Obama had gotten kind of boring. When Ullerup first arrived seven years ago – long before a President Trump was on anyone’s radar – he was struck by how divided America was. In Europe, Mr. Obama was seen as a superstar, but here, Ullerup found “everybody was blocking him.”

“In Europe, people are a little bit surprised that there’s so much negativity about Obama, because it looked like he had gotten America out of the economic crisis much faster than Europe,” Ullerup says.

“What we didn’t focus on was that people had felt forgotten, that their wages didn’t rise,” he says. “People were talking about the unemployment rate going down, but paying less attention to the people who were leaving the labor market.”

Today, he says, America seems more divided than ever. Trump’s campaign talk of NATO as “obsolete” only added to Danish (and European) anxiety about US dedication to the alliance. Ullerup speaks of a recent trip to Virginia Beach for Warrior Week, in which 35 Danish veterans from the Afghan and Iraq wars participated.

“When they came into a restaurant, people would clap or say, ‘Thank you for your service,’ ” he says. “That never happens in Denmark.”

Drama of White House press briefings

Ullerup rarely makes it to the White House briefing room. But for other foreign correspondents, being on scene is where it’s at.

“In the first few months, it was a bit chaotic,” especially compared with the orderly and opaque Obama White House, says Philip Crowther, White House correspondent for France 24 TV since 2011.

Mr. Crowther says he’ll never forget the first full day of Trump’s presidency, when Mr. Spicer came out and “literally shouted at us” about the crowd size at the inauguration.

“The podium was way too big for him,” Crowther says. “The next day, I saw them wheeling it out of the West Wing, and replacing it with one that would suit him better.”

During the campaign, foreign reporters were shut out of Trump campaign events, and they feared their White House press passes would be deactivated after Trump took office. That didn’t happen.

Crowther just finished a year as president of the White House Foreign Press Group, a group of about two dozen foreign correspondents from all over the world committed to maintaining a daily presence in the White House.

“You basically have to remind the White House that you’re there,” says Crowther, a native of Luxembourg with British and German citizenship.

Today, foreign reporters get called on at briefings, as they did under Obama. Though with only one seat in the briefing room reserved for foreign press, most are left standing cheek-by-jowl in the cramped space. But they’ll take what they can get.

‘A nation of survivors’

German radio correspondent Sabrina Fritz is packing up to leave after six years in Washington. And like her foreign colleagues, she is struck by the evolution she has witnessed.

When she first arrived in the US, Ms. Fritz says, the country seemed “very open to everything” – gay marriage, people of other religions, fighting climate change, more vegetables at schools.

“I liked this spirit – all those very, let’s say, European values,” she says. “You have to pay here for your plastic bags, and I thought, wow, a lot of things are changing.”

Over time, Fritz saw that nothing is as simple as it seems. She has traveled the country, talking to workers involved in fracking in North Dakota and cowboys in Wyoming. Like many reporters, she read “Hillbilly Elegy,” the J.D. Vance memoir that offers a window into the lives of the white underclass.

Fritz also made multiple trips to Detroit, and saw a once-great city begin to revive. For her, Detroit’s nascent comeback reflects a glass-half-full attitude that is quintessentially American. “You are a nation of survivors,” she says.

Still, she worries about the future of US-European trade, and about Trump’s decision to pull out of the Paris climate accord. “There’s a danger that the US will fall behind, and become more isolated.”

Still a beacon of democracy?

Is America still a beacon of democracy, as it likes to see itself? TV reporter Chang smiles and quotes “House of Cards” character Frank Underwood: “Democracy is so overrated.”

Chang grew up in Taiwan, “a very vibrant democracy,” he says. “But there are always drawbacks to democracy.”

Sometimes “the people” make the wrong decision, he says, pointing to UK citizens’ decision to leave the European Union. In Washington, expansion of the metro system has been chugging along slowly for years. In China, a project like that would be finished in six months, he says.

Others point to the transparency of the American system as admirable. Slavica of Croatia marvels at the televised open hearing last month of James Comey, the fired FBI director.

“I also love confirmation hearings,” she says. “Whoever the president chooses has to go through a public hearing. That’s a nice test.”

Chang, too, has plenty of positive things to say about the country he has called home for 11 years. He came to the US for graduate school at New York University, and from there, landed an internship at NBC Nightly News.

Chang has been a reporter in the US ever since, and a TV correspondent at the White House since 2010. “I still believe in the American dream,” he says.

Ravens offer new clues about how animal intelligence evolved

We’ve long read about the remarkable cognitive abilities of these birds. (Turns out they like sledding, too; see the video embedded in this story.) Eoin O’Carroll explains why scientists now are looking even more closely at what ravens can teach them.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Could a bird be smarter than a toddler? Researchers in Sweden have found that ravens possess an ability to flexibly plan for events outside their present sensory awareness in a way that surpasses that of chimpanzees, bonobos, orangutans – and even young humans. The research not only reveals that the raven is even smarter than we thought, but also adds to a growing body of evidence that intelligence has evolved more than once. And it refutes the idea that humans and our primate relatives have a lock on complex thought. Some scientists suspect that the complex social environments of corvids – the group of birds that includes ravens, crows, and jackdaws – favored sophisticated cognition. But it could have been the other way around, says one researcher.

Ravens offer new clues about how animal intelligence evolved

According to Norse mythology, the god Odin has two ravens that fly all over Midgard to gather information. Their names are Huginn and Muninn, the Old Norse words for “thought” and “memory.”

The ancient storytellers who bestowed these names on the birds were onto something: A new study finds that ravens can flexibly plan for events outside their present sensory awareness, a cognitive skill once considered exclusive to humans and other great apes.

This research does more than just reveal that the raven is smarter than we thought, that apes’ intellectual abilities are less unique than we thought, and that a mammalian lineage is a not a prerequisite for complex thinking. It also adds to the growing body of evidence that intelligence has evolved more than once.

“It’s pretty amazing in that it works, functionally at least, in a similar way in ravens as in apes, and you don’t see it in many other animals,” says Mathias Osvath, a cognitive zoologist at Lund University in Sweden. “Like monkeys – they don’t even pass the baseline studies.”

Until fairly recently, comparative psychologists studying the evolution of intelligence focused their attention on mammals – mainly primates and rats – and used birds mostly for associative-learning models that measured responses to stimuli. After all, compared to mammals, birds have small brains relative to their bodies, and bird brains lack a neocortex, which in mammals is thought to be the seat of higher-order thinking such as reasoning, problem-solving, language, and delaying gratification.

But today we know that corvids, a group of about 120 bird species that includes ravens, crows, and jackdaws, possess these abilities, no neocortex required. Corvids can make and use tools, barter, recognize individual faces, and remember who shortchanged them in bartering exchanges. They can understand water displacement and mimic human voices. They can grasp the concept of death and its causes. They can infer when they are being watched, suggesting that they possess a theory of mind. They even engage in play.

Smarter than a toddler?

In a series of experiments on five hand-raised ravens described by Professor Osvath and Can Kabadayi, a doctoral student at Lund, published in the journal Science on Thursday, ravens display the ability to think ahead and deliberately prepare for future events.

In one version of the experiment, Osvath and Mr. Kabadayi trained ravens to use a tool to open a box containing a piece of dog kibble, a popular treat among ravens. An hour after researchers removed the tool and the box, they presented the ravens with the tool on a tray alongside a series of nonfunctional “distractor” objects and a smaller food reward. When presented with the box containing the kibble fifteen minutes later, the ravens passed on the smaller reward 86 percent of the time, ignoring the distractors, and picking the correct tool to open the box. When the delay was extended to 17 hours, the ravens picked the right tool 89 percent of the time.

No other animal, aside from apes, is known to be able to pass this test. Even human children under age four typically struggle to get it right. In fact, one of the ravens had to be excluded from further trials after she figured out how to open the reward box using tree bark instead of the tool. She had outsmarted the human experimenters.

In another experiment, where the ravens were trained to use tokens to barter with humans for food rewards, the birds outperformed orangutans, bonobos, and chimpanzees.

“I’m pretty impressed by the levels they showed – the levels of success in all experiments,” says Osvath. “Every single individual was highly significant in all conditions in all experiments.”

How'd they get so smart?

The last common ancestor of humans and birds lived some 320 million years ago, suggesting that these advanced cognitive traits emerged independently in hominids and corvids, using very different brains.

“What’s so interesting to me is that birds couldn’t have really adopted the same solution that we adopted in terms of the neuroanatomy,” says Cameron Buckner, a philosopher at the University of Houston who has studied raven cognition. “So I think one of the most interesting open questions in the field of animal cognition right now is, how on Earth the birds do it with this smaller brain?”

The independent emergence of flexible planning might be an example of convergent evolution, a phenomenon by which an environment selects for strikingly similar adaptations among unrelated lineages. Other examples of convergence include the rise of flight among birds, bats, insects, and pterodactyls, and the evolution of opposable thumbs in primates, pandas, and opossums.

Osvath suggests that corvid cognition could also be an example of a related concept called parallel evolution, in which basic features in related lineages develop into similar traits. “Maybe it is something in the common ancestor of mammals and birds that had had some structures that are really good to build complex cognition upon, given certain selective pressures,” says Osvath.

But whether its convergence or parallelism, what sort of environment selects for intelligence? Like many researchers who study the origin of intelligence, Professor Buckner suspects that it has something to do with having a complex social structure. “Adolescent ravens live in kind of roving bands without a fixed territory where social alliances can change very quickly,” he says. “Who’s your friend and who’s your foe can change very rapidly.”

Later in life, ravens form monogamous pair bonds in which they raise young together and defend their territory.

“This is pretty similar to the kinds of complex and variable lives that humans lead, where you need to be able to update your beliefs about the world very quickly and think on the fly about the results of all kinds of different social encounters and their outcomes,” Buckner says.

“They’re more social than a dog,” says Osvath. But, he says, “We don’t know if they are social like that because they’re clever, or the other way around.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Best lesson yet in Brazil’s anti-graft drive

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

On July 12, former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, known widely as Lula, was sentenced to almost a decade in prison for corruption and money laundering. He is the biggest fish caught so far in a graft probe that has spread across dozens of countries. The current Brazilian president, Michel Temer, also faces corruption allegations. What is perhaps the world’s largest anti-corruption investigation carries lessons for other nations that assume they are trapped in a culture of impunity as Brazil once was. Many reforms are still needed and prosecutors fear ruling politicians can still thwart their work. Yet the momentum toward transparency and accountability seems assured – especially when the mightiest of politicians can fall before the public’s heightened demand for equality before the law.

Best lesson yet in Brazil’s anti-graft drive

President Barack Obama once called him “the most popular politician on earth.” But on July 12, former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was sentenced to almost a decade in prison for corruption and money laundering. Known widely as Lula, he is the biggest fish caught so far in a graft probe that has spread across dozens of countries and snared dozens of politicians. The current Brazilian president, Michel Temer, also faces corruption allegations while his predecessor, Dilma Rousseff, was impeached last year under a cloud of suspicion over a massive kickback scheme involving the state-owned oil company Petrobras.

Yet even as the world notes Lula’s downfall, it should also learn why Brazilians have come to demand honesty in their leaders – and in their daily interactions with government. What is perhaps the world’s largest anti-corruption investigation carries lessons for other nations that assume they are trapped in a culture of impunity as Brazil once was.

“In Brazil there is a consciousness about this problem as there never was before,” said federal prosecutor Deltan Dallagnol in an April talk at Harvard Law School, his alma mater. “Society gave us a lot of support.”

The key idea now more widely supported in Brazil is that of equality before the law, even for someone who was once immensely popular and powerful as Lula. “No matter how important you are, no one is above the law,” said Judge Sérgio Moro in handing down his verdict against the former president, who held office from 2003 to 2011.

Brazil restored its democracy only about a quarter century ago, but the system has been flawed by too many political parties relying on too much money for campaigns and in winning votes in Congress. As political scandals have grown, so too has a small cadre of idealistic and well-paid civil servants as well as a popular movement that has steadily pushed legislation and emboldened the justice system.

Yet it is not enough to simply prosecute powerful people, said Mr. Dallagnol. Society, he says, has “provided a shield.”

Justice officials, for example, have created comic books and board games with anti-corruption themes for children. They have also opened up public records about how politicians spend money. For the first time, prosecutors set up a website to expose pending criminal cases. A popular drive to pass anti-corruption proposals drew more than 2 million signatures. And more than 15,000 people in law enforcement took newly designed courses in how to combat corruption and money laundering.

In 2013, as people became aware of overspending for the 2014 World Cup soccer games in Brazil, anti-corruptions protests began to escalate. Also, prosecutors got a big break in a case known as Operation Car Wash, which exposed huge payoffs to politicians by contractors for Petrobras. The new attitude among Brazilians was essential. “We are pretty aware that without public support that this case is not going anywhere,” says Dallagnol. One poll in January found that Brazilians support the investigations of political figures “to the end, regardless of the outcome.”

Many reforms are still needed and prosecutors fear ruling politicians can still thwart their work. “It’s not enough to take out rotten apples from a basket. You need to change the conditions which make those apples to get rotten,” says Dallagnol.

Yet the momentum toward transparency and accountability seems assured – especially when the mightiest of politicians can fall before the public’s heightened demand for equality before the law.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Justice, not revenge

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By Susanne van Eyl

When we’re faced with aggressive words or actions − or when we hear about them in the news − it can be tempting to respond in kind. But knee-jerk reactions aren’t what impel reformation where it’s needed. Contributor Susanne van Eyl shares how a Bible story about taking the higher road instead of giving in to fury has encouraged her. As the creation of God, divine Truth, we’re all capable of resisting vengeful thoughts. Even in the heat of the moment, pausing to consider how to de-escalate an explosive situation can reveal a path forward that promotes progress.

Justice, not revenge

Justice is an ideal in any society, but how often do we hear the word “justice” used when it is really retribution that’s being sought? “We want justice for this crime” can actually be a cry for revenge. And sure enough, when violence occurs or someone starts a war of words, we may be tempted to physically retaliate or at the very least throw ourselves into the heated exchange.

But what is really needed in order to make progress is de-escalation − and figuring out how to accomplish that is not always easy.

I’ve found encouragement in the Bible. One example is the story of Abigail; her husband, Nabal; and David (see I Samuel 25:1-35). David was a rebel leader at the time who would soon be crowned king. Men loyal to David had protected Nabal’s shepherds, but when David asked that Nabal treat them graciously in return, he refused. Not only that, but Nabal mocked David.

When David heard about it, he was furious and quickly mobilized his army. But bloodshed was averted when Abigail realized what was happening and entreated David to act more nobly and forgive what had been done. He heeded her advice. Instead of waging war against her husband, he had a change of heart and thanked Abigail for keeping him from shedding blood.

Whether we are dealing with violence, neighborhood disputes, or a war of politically motivated words, a knee-jerk reaction can never de-escalate a situation. Like Abigail and David, we can pause and reverse a seemingly downward spiral by seeking a response based on a spiritual understanding of what is true and right and what is erroneous, or unloving. Using Truth as a synonym for God, Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science, urged, “Let Truth uncover and destroy error in God’s own way, and let human justice pattern the divine” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 542). Divine Truth has created us all to reflect its own entirely spiritual nature, which doesn’t include negative traits such as anger, self-will, or hostility. Our understanding of this for ourselves and others can help de-escalate situations that are threatening to get out of control.

Even in the most trying of times we are capable of responding to violent words or actions in a more thoughtful way, rather than simply reacting and seeking revenge in the name of “justice.” It surely takes practice and patience to learn how to do this, but God made us capable of doing it – and this is the kind of justice we all seek.

A message of love

Ready for its close-up

A look ahead

Thanks, as always, for reading (or listening) today. Have a great weekend, and drop by again on Monday. We’ll have a story on a new reform-minded breed of prosecutor taking office across the United States. And one on Europe’s growing taste for celebratory light shows. Until then.