- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for July 17, 2017

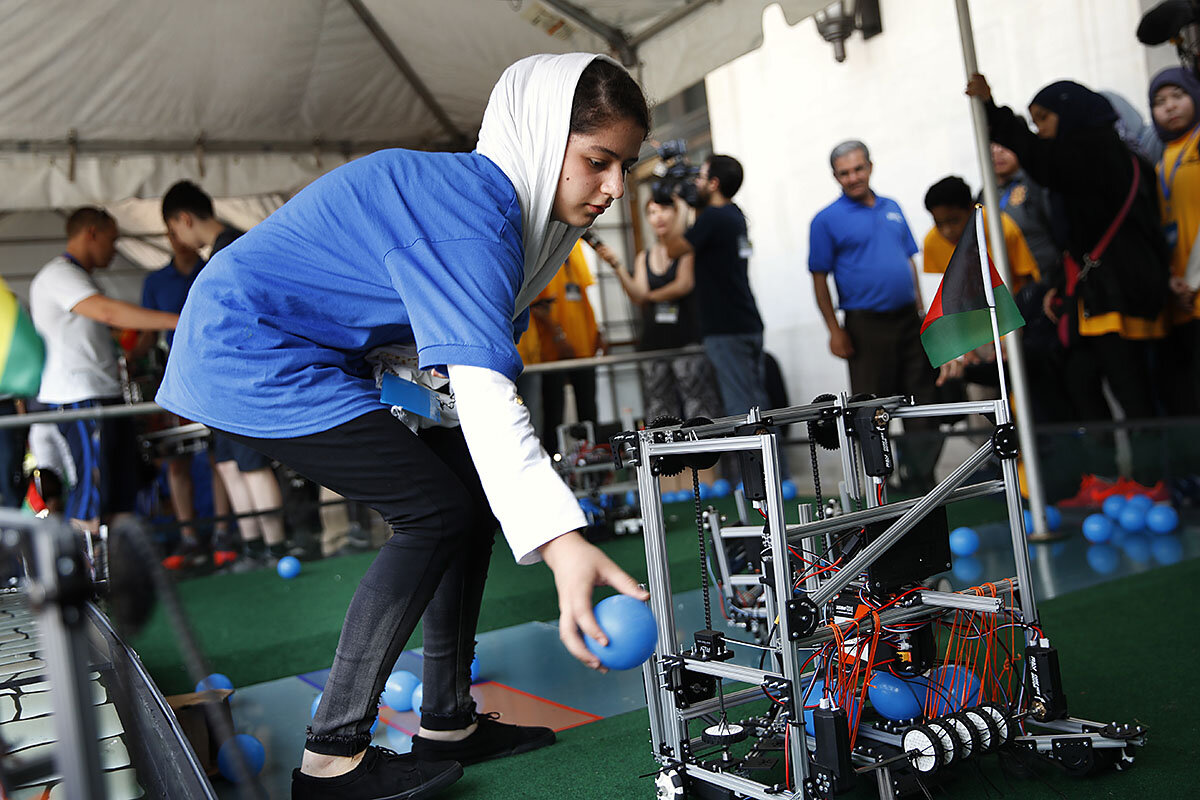

What do Afghan student engineers and Time Lords have in common?

As of today, they’re both women. That’s right "Doctor Who" fans, the 13th incarnation of the BBC sci-fi protagonist will not be a white male. For the first time since 1963, the blue phone booth will be piloted by a woman.

And Afghan girls build robots, don’t they?

Six teenage girls were twice denied US visas. But the Trump White House intervened, and they were allowed into the United States to compete in a robotics event. Teams from 157 nations are now going head-to-head with their home-built robots designed to clean contaminated water (see the Viewfinder photo below).

Afghanistan is still emerging from Taliban rule, when all girls were barred from school. Since 2002, the US has poured millions of dollars into education there. Today, about 40 percent of those in school are girls.

Schooling for girls always makes a society stronger. As educated women, they make better choices, earn more money, and have fewer children.

Schooling also shifts their concepts of what’s possible. As one Afghan robotics sponsor told The Atlantic: “Technology gives us access to new realities. It allows us to dream further.”

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Trump on steel, and the future of global trading rules

Free trade is a core Republican value, right? Maybe not. This story examines why the Trump administration may be willing to adopt protectionist measures.

From his presidential campaign forward, Donald Trump has talked tough about trade, arguing that US workers have been getting a raw deal in world markets. Now his administration is close to a crucial decision about how far to push that rhetoric into action. President Trump argues that US steelmakers are being overrun by subsidized foreign competition. Will his response go after China in particular, or will his administration impose tariffs or quotas that go after a wide range of steel-exporting nations? If he goes broad, the ripple effects could be big. The action would be seen by many as protectionist, undercutting the very system of rules that the United States worked for decades after World War II to build up. But Trump and other Republican leaders are aware that their party base has grown more concerned about the risks of trade. One indicator: Of the 15 states most reliant on manufacturing jobs, all but two were part of Trump’s electoral win last fall.

Trump on steel, and the future of global trading rules

In the next few weeks, America and the world will find out how much bite is behind President Trump’s protectionist bark.

The US and China have just wrapped up 100 days of trade talks, heading into a bilateral economic summit this week in Washington. A month later, the administration will begin renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with partners Canada and Mexico. Then there’s the curious case of sanctions against steel and aluminum imports.

The administration has rattled its sword repeatedly since taking office. But so far the threat of stiff tariffs has remained sheathed.

The delay is understandable: The administration set an ambitious timetable for decisions that are complex and far-reaching, affecting everything from relations with key allies to the price Americans pay for cars and refrigerators. The delay also reflects deep divisions within the administration and a growing structural dilemma for the Republican Party around this key question:

Who’s largely to blame for America’s trade woes: China or the world?

If it’s China, then the United States can sharpen and deploy its existing trade tools more forcefully. If it's the world, then the US might find itself rejecting the global system of trading rules – which previous US Democratic and Republican presidents worked so hard to foster – in order to gain more favorable trade terms in bilateral trade agreements.

That's potentially a huge deal. If the giant US economy changes its tone, that alone undercuts the system now built around the World Trade Organization. And any hoped-for wins for the US aren't guaranteed: Moves like potential US steel tariffs could prompt other nations to ratchet up sanctions of their own – making the pivot toward protectionism a nobody-wins global trend.

“Steel is a big problem," President Trump told reporters July 12 aboard Air Force One on his way to Paris. "I mean, they're dumping steel. Not only China, but others.... They're dumping steel and destroying our steel industry. They've been doing it for decades, and I'm stopping it."

Why impose curbs on imports?

There are at least two reasons the administration might threaten tariffs or quotas – or both – on longtime trading partners and allies.

First, the strategy has worked before. In the 1980s, after a deep recession, President Ronald Reagan used aggressive trade threats to convince Japan and other nations to agree to “voluntary” reductions in exports of cars, steel, and other industrial products to the US. It also provided the impetus for a new trading system, the World Trade Organization, which included new rules that the US had pushed for.

The Reagan strategy “woke up the rest of the world ... to United States’ demands for an improved multilateral system,” says Chad Bown, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

Second, manufacturing has become relatively more important in Republican states (and less important in several Democratic ones) in the last 20 years. That’s forcing the Republican party to begin to reassess how it approaches two core GOP values: free trade and low taxes.

Free trade creates winners and losers, and current GOP orthodoxy makes it hard to help the losers. Raise taxes to subsidize the losers? No way. Income and retraining for those who lose their jobs to imports? Only to the most limited extent.

That laissez-faire approach worked for Republicans during the 1980s and ’90s. Most of the big job losses were concentrated in Democratic strongholds in the Midwest and Northeast. In Republican strongholds in the South and the West, manufacturing jobs were on the rise.

But since 1997, manufacturing jobs have been declining in almost all states (more from automation than trade, but that’s another story). And increasingly, it’s Republican states that are feeling the pinch. Of the 15 states where job markets were most reliant on manufacturing in 1996, 10 voted for Democrat Bill Clinton in the presidential election. By 2017, the last two of the Northeastern states had fallen out of the top 15, replaced by reliably Republican Kansas and a western Democratic stronghold, Oregon. And of the top 15, all but two voted for Mr. Trump, including the Midwestern manufacturing powerhouses: Indiana, Wisconsin, Michigan, Iowa, and Ohio.

“Trump has changed some Republican base opinion on this with anti-NAFTA and anti-China rhetoric,” Doug Irwin, a trade economist and economic historian at Dartmouth College, writes in an email.

The risk: unintended consequences

Solving the problem, however, is a lot trickier than railing against it.

Economically, trade protections are like squeezing a balloon. Try to save jobs in, say, steel factories, and you risk raising prices and costing jobs in the industries that use steel to make appliances and cars.

Then there are the political crosscurrents. Midwest and Plains states are big exporters of agricultural products, Mr. Irwin says, so they’re leery of pulling out of NAFTA and other multilateral trade agreements.

House Speaker Paul Ryan promoted a novel solution to the problem. His proposed border adjustment tax would tax imports, discourage US corporations from locating abroad, and raise money for corporate and individual tax cuts that would improve the business climate. But Trump and other Republicans shot it down, arguing it would constitute a new tax.

The right battle with China?

Finally, there’s the challenge of crafting a coherent trade policy. While there is wide agreement that China is pursuing a mercantilist export push in many key industries, which flouts the spirit of the world’s trading system, it’s not clear that the administration has put together a strategy to counter it.

“Is this [steel action] a one-off or is this part of a broader set of policies and changes that the Trump administration wants to pursue?” asks Nigel Cory, a trade policy analyst at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, a Washington think tank. “There are a range of Chinese policies targeting US high-tech sectors – such as semiconductors, advanced manufacturing, and emerging technologies – which are far more central to US national security and the US industrial base than steel.”

Steel tariffs are also unlikely to gain negotiating leverage over Beijing. Although China is the main culprit behind the world steel glut, existing trade restrictions have already cut steel imports from China by 75 percent from their level two years ago.

So new tariffs, if not narrowly targeted, would mean seriously reducing steel imports from major US trading partners like Canada, South Korea, and Mexico, potentially undermining joint efforts to bring the Chinese into line. The European Union has already threatened to retaliate if it’s targeted by US sanctions.

Will Trump risk alienating allies and challenge the rules of the world trade system to create, at best, a few thousand jobs in the highly automated steel industry?

Trump has set the stage for using an unusual rationale for reducing imports – national security – via a rare so-called Section 232 action. Trump’s US trade representative, Robert Lighthizer, a veteran of the Reagan-era disputes, is again pushing aggressive trade measures to counter what he says is widespread international abuse of free-trade rules.

The context for such moves has been flipped on its head, however. At a time when the US was coming out of a deep recession, free-trader Reagan used the voluntary restraint agreements to head off more protectionist measures from Democrats. Now, with an economy firing on most cylinders, a Republican administration is threatening to initiate protectionist measures.

It's highly controversial even within the Trump administration. With the president vowing to move forward, the open question is whether it will work as in Reagan’s day or tilt the world closer to a path of beggar-thy-neighbor protectionism.

Share this article

Link copied.

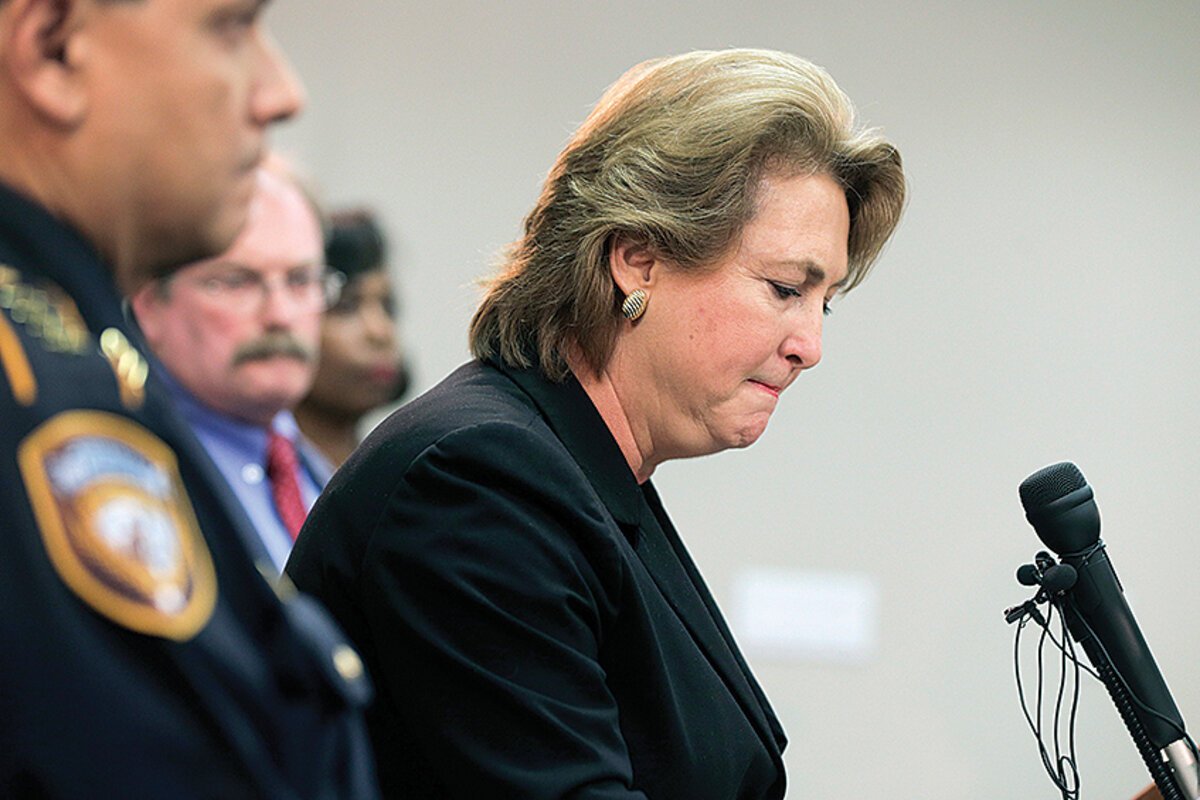

Within ranks of US prosecutors, reformers now rise

There are different approaches to meting out justice. Here we look at how one Texas prosecutor, with “not guilty” tattooed on his chest, enforces the law.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 14 Min. )

Mark Gonzalez, the much-tattooed, motorcycle-riding district attorney in Texas’s Nueces County, is a rebel with a cause and a lot of legal clout. He is part of a new breed of prosecutor taking office across the United States with a reform-minded approach that sounds more Clarence Darrow than Clarence Thomas. From Texas to Florida to Illinois, many of these young prosecutors are eschewing the death penalty, talking rehabilitation as much as punishment, and refusing to charge people for minor offenses. While their numbers are small, they are taking over DA offices at a crucial moment. Faced with crowded prisons and the high financial and social costs of incarceration, many states have been moving away from the strict law-and-order approaches of the past, emboldened by justice advocates on the right and left. Yet in Washington, the tone is just the opposite. New Attorney General Jeff Sessions, backed by President Trump, wants to revive stiff sentences for drug offenders and tougher laws in general. Thus the new prosecutors could become crucial players in what is shaping up as a struggle for the soul of the US justice system. “[W]e’re being watched nationally – in part because I’m a defense attorney with a ‘not guilty’ tattoo on my chest – but also because of some of the things we’re trying to do,” Mr. Gonzalez says. “We’re trying to change things.”

Within ranks of US prosecutors, reformers now rise

The new district attorney of Nueces County here in southern Texas strolls around the local courthouse in cowboy boots and a crisp brown suit with a colorful tie and matching pocket square, flashing a smile as wide as the grille of the Ford F-350 pickup he drives. On the surface, at least, he seems like your stereotypical Texas lawman – the one you see in movies wearing a Stetson and spurs, delivering justice and colloquial quips through a lip filled with chewing tobacco.

But then he tells you his name, Mark Gonzalez (the last name pronounced with a distinct Latino lilt). Then he might mention the trouble he’s had earning the trust of local law enforcement, in part because he’s listed as a gang member (he isn’t one, but more about that later). Eventually, he may talk about the raft of progressive changes that he’s beginning to implement in Nueces County, such as helping young offenders go to trade school instead of to prison.

There’s his background as a defense lawyer, his criminal record (he once pleaded guilty to driving while intoxicated), and finally this: the tattoo. Inked across his chest are the words “not guilty” – a bit of bravado from his defense lawyer days that he feels holds just as much relevance to his new job, which he won in a narrow election victory last November.

“I think every prosecutor should have in the back of their minds and in their hearts that everyone is not guilty until I prove my case,” he says. “I think my tattoo is something my office needs to always think about, and DA offices across the state and across the country” need to think about the concept, too.

Mr. Gonzalez is a rebel with a cause and a lot of legal clout. He is part of a new breed of prosecutor taking office across the United States with a reform-minded approach that sounds more Clarence Darrow than Clarence Thomas.

From Texas to Florida to Illinois, many of these young prosecutors are eschewing the death penalty, talking rehabilitation as much as punishment, and often refusing to charge people for minor offenses.

While their numbers are small, they are taking over DA offices at a crucial moment. Faced with crowded prisons and the high financial and social costs of incarceration, many states have been moving away from the strict law-and-order approaches of the past, often emboldened by justice advocates on both the left and right.

Yet in Washington, D.C., the tone is just the opposite. New Attorney General Jeff Sessions, backed by President Trump, wants to revive stiff sentences for drug offenders and tougher laws in general. Thus the new prosecutors could become crucial players in what is shaping up as an epic struggle for the soul of the US justice system.

“It does seem to be a new and significant phenomenon,” says David Alan Sklansky, a professor at Stanford Law School, of the new prosecutors. “It’s rare to see so many races where the district attorney is challenged, where they lose, and where they lost to candidates calling not for harsher approaches, but for more balanced and thoughtful, more restrained, more progressive approaches to punishment.”

Perhaps no one in the US is more important to dispensing justice than a prosecutor. Indeed, Robert Jackson, a Supreme Court justice in the 1940s and early ’50s, said a prosecutor “has more control over life, liberty, and reputation than any other person in America.”

Prosecutors control the two most important decisions in the criminal justice process, experts say: levying charges and negotiating plea bargains, which is how some 95 percent of all court cases are resolved. As Kim Ogg, the new district attorney in Texas’ Harris County, puts it: Prosecutors “hold the key to the front door of the courthouse and the back door of the jail.”

Yet they have been one of the least scrutinized players in the criminal justice system. For much of the past century, it wasn’t unusual for district attorneys to stay in office for decades, winning reelection after reelection, often running unopposed, and trying to be as tough on criminals as possible.

But with the elections of Gonzalez and Ms. Ogg, and more than a dozen similarly reform-minded prosecutors, that appears to be changing. And given the discretion prosecutors enjoy in determining the fates of those arrested, the future of justice reform could be shaped by how this trend develops.

The new reformers, to be sure, represent only a fraction of the nation’s 2,500 district attorneys. But those numbers could climb as liberal activists such as billionaire George Soros increasingly target DA elections. Moreover, a generational divide may be developing, experts say, between these prosecutors – who came of age in an era of low crime – and an older generation of DAs shaped by the war on drugs.

Capital punishment has become a marker of how these new DAs seek to exercise their discretion in different ways. Aramis Ayala, the new district attorney in Florida’s Orange County, has received the most national attention for her refusal to seek the death penalty in any case, but she is not the only one. Beth McCann, the district attorney in Denver, is doing the same thing, and Larry Krasner, who is poised to become the next DA in Philadelphia, is an opponent of capital punishment as well.

Others are carrying out more subtle reforms. James Stewart, the district attorney in Caddo Parish, in Louisiana, took control of an office with a record of aggressive capital convictions and has quietly not gone to trial on a death penalty case since being elected in 2015. Kim Foxx, the new state’s attorney in Cook County, in Illinois, announced in March that her lawyers will not oppose the release of detainees from jails who can’t afford cash bonds of as much as $1,000. Ogg, who took over an office plagued by a recent history of unethical prosecutions, dismissed three dozen prosecutors in leadership positions and has hired a former judge to lead a newly formed ethics office.

Gonzalez is just beginning to define his reformist approach. He is still filing death penalty cases but hasn’t decided if he will continue to support using society’s ultimate punishment: He wants to wait to see what Nueces County residents say about it – particularly juries.

The new DA has refused to prosecute any misdemeanor marijuana offenses. Instead, offenders can get their case dismissed if they pay a $250 fine and take a drug class within 30 days. The policy has kept people with minor crimes from filling up jails but has made the county money, too: In the first four months, it has pulled in $320,000, wiping out a $3,000 deficit in the office’s pretrial diversion program.

Gonzalez has started an intervention program for first-time offenders facing misdemeanor charges for domestic abuse in partnership with a local women’s shelter. It requires those accused of domestic violence to sign a confession and attend a 24-week class on family violence in exchange for having the case dismissed.

He’s now trying to craft a similar diversion program for people arrested for driving with invalid licenses. He’s trying to partner, too, with local industries and trade schools on an initiative that would require younger violent offenders to graduate from a vocational school in order to get their cases dismissed.

“Jail isn’t always the answer. Convictions aren’t always the answer, especially if there’s history showing that convictions only show you’re going to get another conviction,” says Gonzalez. “We have some conservative people out there, but they’re interested in being smart and economic and efficient, and that’s how we have to move the courthouses into current times.”

Gonzalez’s views, like those of many of the new prosecutors, are rooted in both personal experience and shifting notions about criminal justice issues. One particularly formative moment for him came the night he had been at a party and, after having a few drinks, went out looking for a girl he knew. The cops found him first. They charged him with driving while intoxicated (DWI). He was 19.

Gonzalez didn’t know any lawyers, so he brought his mother to court with him. She told him that if he just pleaded guilty then the judge would be nice. He did so, and got the standard sentence: a fine, one year of probation, and 30 hours of community service.

That could well have been the end of the story, but then he saw a Navy pilot in the courtroom – charged with the same crime – get off with the help of a lawyer. Until then, he’d been considering becoming a dentist. “That’s when a light went off in my head: I’m going to be a lawyer so my friends don’t have to bring their mom; they can bring me,” says Gonzalez.

Some of his friends would probably need an occasional lawyer. Gonzalez grew up in tiny Agua Dulce, a poor farming community of about 800 people in southeastern Texas. He got his first tattoo, a portrait of Jesus, on his 15th birthday as a present from his father. His upper body is a wallpaper of ink now.

Previous generations of Gonzalez men had been oil field workers, but after graduating from high school, in a class of 25 students, he became the first person in his family to go to college. Construction work paid his way through Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, and becoming a father at 21 forced him to grow up quickly. Six years after his DWI arrest he had a degree from St. Mary’s University School of Law in San Antonio. He was the first in his hometown ever to go to law school.

“When you’re young, you do stupid stuff,” he says of his arrest. “I got caught for stupid stuff, and I got a chance. I think [other] people deserve that chance. But if they get that chance and mess up, my hand will be heavy.”

Gonzalez’s maverick image has been reinforced by the time he spends on the back of one of his Harleys (he has three of them and two other motorcycles). He is a member of the Calaveras motorcycle club, which some local law enforcement officials consider a gang. Hence his listing in their computer database as a gang member. Yet he proudly admits to being a part of the group – one that, he notes, does charity drives for kids.

Gonzalez’s work as a defense lawyer has shaped his unorthodox views as well. He often saw his clients overcharged by county prosecutors and pressured to plead guilty in exchange for lesser charges. “I just got angry at what I was seeing and the things that were going on...,” he says. “The [plea] deals we were getting offered were just outrageous.”

It’s a major reason he ran for district attorney. Unlike Ogg, Gonzalez didn’t receive donations from Mr. Soros in the campaign, which would suggest that the new progressive prosecutor movement isn’t dependent on the activist’s largess alone.

Yet Gonzalez has become a highly visible member of the new progressive prosecutorial class. Within weeks of entering office, he began getting invitations to join various national groups – from the John Jay College-based Institute for Innovation in Prosecution to Fair and Just Prosecution, a nonprofit led by former prosecutor Miriam Krinsky.

On this day, unopened boxes still clutter his office and a decorative cattle skull waits to be hung on the wall. Charismatic and energetic, Gonzalez moves from room to room, chatting with lawyers and cracking jokes (he tells a shorter colleague that he should celebrate his birthday at the local equivalent of a Chuck E. Cheese). When he’s not standing patiently in front of a judge, Gonzalez seems in constant motion.

He is also planning a trip to Seattle to learn about an ambitious diversion program, one that channels low-level drug offenders into treatment programs before they are arrested. This allows them both to get help and avoid having a criminal record. The initiative is being piloted by veteran King County Prosecuting Attorney Daniel Satterberg.

Still, as a DA in law-and-order Texas, Gonzalez recognizes that he can’t move too quickly with his reforms. “I’m not sure we’re ready for that,” he says of the Seattle program.

His approach so far mirrors that of Ogg, who is also a former defense lawyer. Both are members of Fair and Just Prosecution, and both are diverting those arrested for possession of marijuana – a simple misdemeanor offense – away from jail. Yet behind what many of these progressive prosecutors are trying to do lies a more fundamental goal: restoring trust in the law.

“In the last decade the American people have literally lost faith in the fairness of our justice system,” says Ogg. “If they think we’re rigging the system, or trying to force outcomes, then they’re not going to participate, and to me that is a huge threat to our democracy.”

A decade ago, that public dissatisfaction was already deeply embedded in Wisconsin’s Milwaukee County. The county had more than 24,000 people in jail at the time – twice that of the entire state of Minnesota – and John Chisholm was elected after the retirement of a district attorney who had been serving for 40 years in part because he said he would address that.

“There was a strong sentiment in the community that we were sending too many people to jail,” he says. “My argument was, if I can take an approach that increases public safety but reduce our reliance on jails and prisons, that’s potentially a good thing for everybody.”

Ten years and four reelections later, Mr. Chisholm thinks his philosophies may be gaining traction in the prosecutorial community. One reason is increased public interest in the criminal justice process, cultivated by national coverage of controversial police shootings and bipartisan efforts to reduce mass incarceration.

“The gut instinct response [to crime] is, ‘We’ve got to pass another law, a tougher law, get tougher on these individuals.’ That’s just a basic response to fear, and it’s worked for a long time,” he says. “I think people have come to understand the complexity [of the system] to a greater degree, and there’s a little less willingness to go to the knee-jerk responses.”

Maybe so, but the mood in Washington is much harder-edged. Attorney General Sessions has already restored mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses, and personally asked congressional leaders to let him prosecute medical marijuana providers.

Sessions says that the recent upticks in violent crime in some cities represent “a dangerous new trend” and that the Justice Department “can’t afford to be complacent.” His concerns are rooted in his experience as a prosecutor in Alabama in the 1980s, at the height of America’s violent crime epidemic.

“They saw what the failure to respond aggressively in the ’70s led to, so they’re skittish about going to what they saw as soft approaches,” says John Pfaff, a criminologist at Fordham University who studies prosecutors.

The divergent philosophies of the Trump administration and some of these new DAs are a reminder that, with more than 2,000 prosecutors across the country, there is no cookie-cutter approach to fighting crime. “Hard” and “soft” approaches are constantly colliding and moving through the nation’s courtrooms in cycles. Indeed, many of the more liberal reforms being instituted today have been tried before.

What Ogg, Mr. Satterberg, and some of the other prosecutors are doing with drug offenders is essentially what local prosecutors in New York did in the 1990s. Back then – while the draconian Rockefeller drug laws were still in effect, no less – major DA offices across the state implemented programs to divert nonviolent felony offenders from prison to drug treatment centers.

“We didn’t wait for the Legislature to reform the statutes; we did it on our own,” says Bill Fitzpatrick, who has been the DA in New York’s Onondaga County for 25 years and is chairman of the National District Attorneys Association.

Nor have all these latest reforms come about just because Soros and other liberal activists began pouring money into local district attorney races. In Colorado’s Gilpin and Jefferson Counties, for instance, District Attorney Pete Weir has implemented multiple programs that emphasize treatment over prison and instituted specialty courts, including ones tailored to veterans and adults with serious mental health issues. Yet Mr. Weir, who was elected to office in 2012, beat a Soros-funded candidate in 2016.

“I think prosecution in general – and certainly my approach to prosecution – has evolved over the almost four decades I’ve been involved in the [criminal justice] system,” says Weir, who has also served as a staff prosecutor and judge. Weir argues that helping defendants is actually good for communities. It reduces the chances that they’ll commit other crimes.

“There’s an impression that a prosecutor is just the reverse side of the coin of a defense attorney,” he says. “Nothing could be further from the truth.”

Gonzalez certainly values having people with experience on both sides of the justice system. His office is rich in defense bar experience – not least in his top assistant, Matthew Manning, who worked with Gonzalez in private practice before he ran for district attorney.

Mr. Manning is a critic of the death penalty, and “pretty social justice-minded.” His office features framed news clippings of some of his major cases as a defense lawyer, a “Do the Right Thing” poster from Spike Lee’s film about racial tension, and a large painting of Martin Luther King Jr. getting arrested.

“I didn’t have some aspiration to be a prosecutor, but once I thought about the good we could do, I thought it was an extraordinary opportunity,” he says.

Gonzalez’s lawyers do prosecute aggressively – Manning got a gang member a 48-year prison sentence in a recent murder trial – but their defense experience informs their reform efforts to a significant degree.

“You can’t really fully appreciate how important it is to play fair as a prosecutor unless and until you stand next to somebody who could have their entire life taken away from them if the prosecutor doesn’t play fair,” says Manning.

While Gonzalez has made national headlines with a few high-profile moves so far – such as his marijuana diversion policy – these days most of his time is spent dealing with the bureaucratic minutiae that come with running a small government office. Jobs in local DA offices are among the lower paid positions in government, so turnover is high. In his first four months, Gonzalez lost three lawyers to more lucrative jobs. But on this day he is delivering a compelling pitch to one eager new candidate.

“One of the benefits we do have here is we’re being watched nationally – in part because I’m a defense attorney with a ‘not guilty’ tattoo on my chest – but also because of some of the things we’re trying to do,” he says.

“We’re trying to change things,” he adds. “I think everyone’s changing a little bit. The culture is changing.”

Correction: This article has been updated to correct the name of the nonprofit Fair and Just Prosecution.

In Kathmandu, carvers restore heritage – and revive a craft

Imagine, after an earthquake, that you’ve been hired to restore Italy's Sistine Chapel. What an honor for an artist and a craftsman. But in Nepal, that honor may only bring the wages of someone who carves souvenir trinkets.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

-

By Atul Bhattarai Contributor

Char Narayan temple, just south of Kathmandu, Nepal, has been rattled by earthquakes since 1565. Nepal’s 2015 quake might have been just one more. Instead, as the temple lurched back and forth at four minutes to noon, centuries of heritage became a heap of rubble. For Kathmandu’s carvers, however, rebuilding efforts have let them resurrect more than the storied pagodas. Long consigned to plain staples, many had fled the profession. Now they are using ancestral skills they have trained for their entire lives, but seldom had occasion to use. “For us Shilpakars, wood is our work by birth and caste,” says Tirtha Ram Shilpakar. “Our fathers, our grandfathers, everyone we know did this.” Reconstruction hardly guarantees the craft’s future, though – nor the artisans’ financial security. Past and present also tug at each other among the projects' architects: Some seek to freeze the temples in time, while others see them as living pastiches, renewed by each generation. Tirtha Ram feels he’s swallowing losses to take part in the restoration project, but is buoyed by its significance. “The thing about temple work is, I can tell people I did even this,” he says. “Who do I tell that I built a closet?”

In Kathmandu, carvers restore heritage – and revive a craft

In a workshop inside the courtyard of a 17th century palace, Tirtha Ram Shilpakar is surrounded by the guts of ancient temples. The floor around him is crowded with carved wooden beams, ashy with age. The walls are lined with pillars and detached windows. A few steps off lies an 11-ft.-wide doorway, dissected on the floor.

Tirtha Ram sits hunched in a corner, one leg curled over a giant beam. Amid the scream of power saws and the blare of '80s Bollywood hits, he carves into the beam, hammer and chisel in hand, copying a floral pattern from a sketch beside him.

As the workshop’s naike, or leader, he makes occasional rounds of the premises. Of the 24 craftsmen he oversees here, most share his family name: “skilled worker” in Nepali, although they also go by Sikarmi, or wood-worker. These men were inducted into the craft before they started the first grade, driving nails and planing surfaces in family workshops; most abandoned school before their fifteenth birthdays to work full-time.

“For us Shilpakars, wood is our work by birth and caste,” Tirtha Ram says. “Our fathers, our grandfathers, everyone we know did this.”

Their work, however, is a far cry from that of their ancestors, the temple-builders of the Malla period, who raised the elaborate tiered pagodas that Kathmandu is famed for. Since patronage for temple construction petered out some 250 years ago, Shilpakars have been consigned to the plain staples of modern woodwork: furniture, decorative windows, gates, and tourist merchandise, often crude miniatures of statues and parts of these very temples. Feeling unappreciated and underpaid, many have fled the profession, leaving it close to its demise.

But their future took a turn on April 25, 2015, when a 7.8-magnitude earthquake tore through Nepal, killing nearly 9,000 people and wreaking havoc on centuries of heritage in the Kathmandu Valley. Among the structures flattened by the quake were Hari Shankar and Char Narayan, 18th- and 16th-century Newar temples in Patan Durbar Square, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust (KVPT), which has restored sites in the city since 1991, took up responsibility for rebuilding these two temples by 2019. Shortly after, Tirtha Ram, taking a hiatus from his private workshop, was recruited into the project full-time, alongside other craftsmen from nearby Bhaktapur. For more than two years his team has been resurrecting Hari Shankar and Char Narayan, using ancestral skills they have trained for their entire lives but have seldom had occasion to use.

But if the earthquake has breathed new life into their craft, it has also exhumed strains between the past and present: between the role of temples as relics, and as functional spaces today; and between Kathmandu’s storied heritage, and the needs of the men restoring it.

Historically, Shilpakars have been stereotyped as manual laborers rather than artists, robbing them of income and prestige, explains Rohit Ranjitkar, KVPT’s country director. He calls them “the real heroes of conservation.”

While the restoration work may not remedy their financial woes, Tirtha Ram says it carries “glory.”

“Lattice windows are simple to make,” he explains, referring to a popular tourist replica. “But this is heavy, very heavy. Even most Shilpakars can’t do it: it’s special work.”

'As different as earth and sky'

Since it was erected in 1565, Char Narayan, the oldest temple in Patan Durbar Square, had been rattled by earthquakes every century. Had it received proper upkeep, the 2015 quake might have been just another entry to that list.

Instead, as the temple lurched back and forth at four minutes to noon, the immense weight of its masonry sheared off weaker joints and knocked out its base columns. The roof’s overhang folded like an umbrella. Beams snapped in midair or were crushed by falling debris. Carved doorways and windows crashed to the ground, shattering instantly. In seconds, the whole structure was a heap of rubble.

In the days that followed, KVPT sifted through the wreckage to identify what could be kept – it was “a huge jigsaw puzzle,” Mr. Ranjitkar recalls. Most parts were deemed salvageable, although pillars and other weight-bearers would have to be rebuilt from scratch. Cracked and scarred portions would be excised and spliced in with carved blocks of rosy new wood. “Like patching up old jeans,” says Bijay Basukala, who supervises the craftsmen.

Today in the workshop, Pushpa Raj Shilpakar, one of the project’s most gifted carvers, is bent over a statue of a two-toned goddess: half old, half new. She has gone stub-nosed, details having blurred through the centuries. Flicking away woodchips, Pushpa Raj carves her new hand into a plain block, shaping fingers, and with his finest chisel, her minuscule nails.

Asked if he had worked on similar designs before the earthquake, he gave a wistful smile. “Nothing like this,” he says. “These designs – it’s like they were made by a god. I still can’t understand how they did it.”

Kathmandu’s Newar temples stand apart from other Asian architectures for their maddening irregularity. It’s clear carvers for temples like Char Narayan were never issued firm blueprints, architects say, allowing them to work individual styles and whimsies into the patterns. A row of columns might appear identical, but peer closer and every element is done up differently: the flowers, figures, even standard flourishes.

“Extraordinary architecture,” Ranjitkar calls it.

But only a handful of conservation projects stress fidelity to original designs. The rest are tendered out to contractors who are more invested in minimizing costs than upholding quality, Tirtha Ram says. He reckons if he were to put as much care into tourist pieces as the temples, they would take four times as long to complete. A single large window would consume four months of uninterrupted work and cost far too much to stand a chance in the market.

In Tirtha Ram’s private workshop in Bhaktapur, his colleagues fashion windows for two traditional guesthouses in Patan Durbar Square that caved during the earthquake. Hanging on the walls are tourist windows made of cheaper wood with shallower carvings, like those on the face of a coin.

“This is a flower. This is also a flower,” he says, pointing to the filigrees on one window and the plain patterns on the other. “But they’re as different as earth and sky.”

The cost of craft

Despite their work with KVPT, the craftsmen live in a state of financial uncertainty. For generations, their families eked out a small living building furniture and gates for homes. After Nepal opened up to visitors in the 1950s, a tourist market emerged. But for these goods, cost competes with craft, and work is hurried to meet buyers’ budgets and deadlines: delicate fretwork and subtle details are left out; complex traditional wood joinery is swapped for nails.

The more successful craftsmen keep workshops in Bhaktapur, where they made $100 to $300 a month before the earthquake. Demand for tourist merchandise has since evaporated, and unsold statuettes, returned from the shops, stand in dusty rows in Pushpa Raj’s bedroom. Even when they were marketable, however, shopkeepers purchased his pieces for $6 to $12 and resold them for up to $50, taking home most of the gains.

“You can’t keep track of profits in the shops,” Pushpa Raj says grinning. “The shopkeepers are wily. They tell the tourists, ‘This is a masterpiece!’ and cheat them.”

Tirtha Ram feels he’s swallowing losses to take part in the KVPT project, where craftsmen receive $12 to $15 for six hours of work per day. In private workshops, where they are compensated per contract, the daily wage averages only $11 – but in times of need, they sometimes power through 18-hour shifts, wrapping up orders ahead of time to pocket larger profits.

And this has been a time of need. Since 2015, like many in Nepal, Pushpa Raj and his family have lived in temporary housing, a shed of corrugated tin sheets arranged into walls and ceilings. Tirtha Ram has crowded into a relative’s house with his wife and two children, one of whom has cerebral palsy. Both men’s family homes were battered by the earthquake, and neither knows if he will ever be able to gather the estimated $30,000 needed to rebuild.

“If you can build a house for yourself, your life is successful,” says Surya Bahadur Shilpakar, a colleague in Tirtha Ram’s workshop. “We build one house with difficulty – with difficulty – and only a few of us at that. Everyone says it's important work, our profession. Our ancestors said don't leave it. But people who have done other things earn so much more.”

Many Shilpakars feel indentured to the trade, unable to pursue better-paid jobs because of their truncated schooling, Surya Bahadur says. He would rather his children not join their ranks. Several of the craftsmen’s younger relatives, seeing the precarious finances they would inherit, have shunned the grueling apprenticeship to qualify as a carver, a rite that can take upwards of a year. This trend could spell the end of traditional woodcarving.

Tirtha Ram is buoyed only by the significance of temple restoration, which he frames as his “actual” work, as opposed to his “commercial” work.

“The thing about temple work is, I can tell people I did even this,” he says. “Who do I tell that I built a closet?”

The present past

As the Shilpakars attempt to reconcile their heritage with the future of their craft, a similar tension plays out among the architects. KVPT seeks to freeze the temples in time, as archives of the past, but they have always been pastiches, renewed piecemeal by successive generations of craftsmen. In previous centuries, damaged wood would have been switched out and tossed into a fire.

Ranjitkar considers the dizzying variety of designs in the temples a part of the historical record, and requires they be reproduced stroke for stroke – including mistakes. He fears deviations might “mislead historians.”

But replication is always inexact, says Niels Gutschow, an architect who has consulted for restoration projects in Kathmandu since the 1970s. Purists, horrified at the idea of “recreating” designs, would leave replacements shorn of decoration. But Dr. Gutschow maintains that in Nepal the craftsmen, as descendants of the “original carvers,” are “able and even entitled to recreate what is lost.”

Sirish Bhatt, a consulting architect for KVPT, notes her admiration for the temple’s history is a world away from how the temple is popularly viewed. Valuing something simply because of its age is a foreign concept in Nepal.

For most Nepalis, “this is not art,” she says, gesturing toward the temples in the square. “This is not a dead monument. In the West, these places become museums. It’s so formal, you pay an entrance fee. There’s none of that here. Maybe it’s a bit chaotic, not clean, but it has life, I feel. It’s part of the everyday.”

In late afternoon, as the craftsmen trickle out of the workshop, Patan Durbar Square beats with activity. Schoolchildren gather in chattering groups. Tourists stroll between temples wrapped in scaffolding, cameras bouncing off their bellies. Circulating the open space are boys selling cotton candy, hoisting their suspiciously pink wares on long sticks, like standards. On a ledge facing the stump of Char Narayan, an old man naps as a teenage couple holds hands surreptitiously a few feet away.

Inside, asked if he would have gone about restoration in the same way as KVPT has, Tirtha Ram hesitates. “No,” he says finally. “They want to save the wood.” He points to a frieze depicting a faceless goddess, her features weathered away. A crack snakes down half the length of her body.

“This will hold, but it’s like the temple is missing teeth,” he says. “If we had to do it, we would use old pieces too. But we would mostly build new. After all, whatever we make now, it will be seen for another 500 years.”

Fireworks? Non. 'Son et lumiere' shows light French summer nights

Forget pyrotechnics. The French paint with light, offering fresh perspectives on history and architecture.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

In 1952, Paul Robert-Houdin officially introduced the world to a brand-new art form. He projected special lights, set to accompanying sound, onto the facade of the Chateau de Chambord, a Renaissance castle in the Loire Valley, in the first performance of what is now known as son et lumiere. Today, visitors continue to flock to the light shows, often set to historical narratives, projected onto gothic abbeys or baroque monuments, both in France at large and around the world. “Chroma,” the show running on the cathedral in Amiens, France, through the end of the summer, highlights how both the past and the technology influence the art form, says Marc Vidal, director of Spectre Lab, which created the show. "It’s not the effects for the sake of effects,” he says. “The animations highlight the building, the architecture ... the pure history of the cathedral.”

Fireworks? Non. 'Son et lumiere' shows light French summer nights

I was feeling slightly wistful about our family missing the Fourth of July in the US – until the following weekend when we found ourselves in front of the cathedral of Amiens at nightfall, watching its facade splashed in color, the light show giving the sense that the Gothic cathedral, unmoved since the 13th century, was dancing before us.

Forget fireworks, we had son et lumiere.

While the French are old hands at the artform, I had the feeling we were experiencing the show “Chroma” the way spectators did in 1952, when Paul Robert-Houdin officially introduced them to a brand new genre. The architect and curator, fittingly also the grandson of a famous French magician, projected special lights, set to accompanied sound, onto the facade of the Chateau de Chambord, a Renaissance castle in the Loire Valley, playing with spectators’ sense of place and emotion.

The late French public official Jacques Rigaud was sent to Chambord to observe those rehearsals and premiere, and recalled beholding his first son et lumiere with a sense of “wonder.” “We had the feeling that a new way of discovering and understanding monumental heritage was perhaps being born,” he wrote in Le Figaro in 2002, in a commemorative piece marking the 50th anniversary of the form, noting that large numbers came to witness the show through the end of that summer of 1952.

In fact, 65 years later, visitors continue to flock to son et lumiere: to watch light shows, often set to historical narratives, projected onto gothic abbeys or baroque monuments, from its birthplace in the Loire Valley, to France at large, and today around the world.

Fireworks have their place in France too, especially during the country's annual independence day fête. Last weekend's Bastille Day, which President Trump attended, looked in many ways like the Fourth of July, save for the Eiffel Tower in the background of the grand feu d’artifice display in Paris. But son et lumiere is, I dare say, that much more mesmerizing.

The art form has evolved over time with technology, with 3D projection mapping and changing cultural sensibilities. Marc Vidal, director of Spectre Lab, which created the Amiens show running through the end of the summer, says that “Chroma” was meant as a new experience for Amiens. The city has put on a light show for over a decade and a half, but the new version was meant to be something less historical, and overall more fun – which explains the punchy music and bursting colors – without forgetting the point of the show.

"It’s not the effects for the sake of effects,” he says. “The animations highlight the building, the architecture ... the pure history of the cathedral.” The final 30 minutes of Chroma are particularly moving, as lighting paints in the ornate sculptures that adorn the cathedral's principal facade, allowing visitors to experience it in polychrome the way it would have looked in the Middle Ages.

Mr. Vidal says the birth of son et lumiere likely owes to the tradition of grand fêtes tracing back to King Louis XIV at Versailles, France’s pioneering in cinema and projection, and its abundance of historic monuments.

Yet it is but a subset of light used as art that’s taken off around the world, including in the US.

Bettina Pelz, a German curator who wrote a chapter on art in the new book “Light beyond 2015,” after the UNESCO International Year of Light, says that light-related projects in the public space have grown in the past 15 years. While usually lumped together, they vary widely in their aesthetics and technical capabilities – not to mention in the visions of curators or local officials and institutions.

Europe remains the heartland of the art. Light shows, like the famous Festival of Lights in Lyon, have inspired many others. Such shows are common in northern Europe as the winter solstice nears. Many Asian projects today link with European initiatives, says Ms. Pelz.

“Light is exciting to the eye,” Pelz says. “We can detect the changes caused by light but light itself remains invisible. This interplay of visible-invisible is quite stimulating.... Light-based works play with the appearance and disappearance of space, with the change of position and perspective, as well with the performative qualities of color and shape. They stage the inextricable link between the image and its perception. Instead of observing an artwork, the viewer is experiencing it. Viewing and imaging become entangled processes.”

Difference-maker

A Hawaiian farm that’s regrowing cultural values

Our next story is superficially about growing taro on a Pacific island. But really, it’s about nurturing people – and restoring self-respect through rediscovering Hawaiian values.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When Dean and Michele Wilhelm bought the property for their farm, it was a tangled rainforest that no developer wanted to touch. Today, they use taro farming as a means of teaching Hawaiian values and mentoring youths facing challenging circumstances. Some researchers have suggested there are links between an erosion of Hawaiian culture, Western influence on the islands, and higher rates of substance abuse, poverty, mental illness, and other social problems among Native Hawaiians. Drug use is particularly prevalent among youths: About 60 percent of Native Hawaiian students have used drugs by 12th grade, compared with 46 percent statewide, according to statistics from the Hawaii State Department of Health. The Wilhelms hope that instilling Hawaiian values in at-risk youths will help bolster their sense of self-worth and encourage them to contribute to society. And taro farming is a vessel for that culture-based mentoring. “[Dean] tells us that the purpose of the place is to grow people,” says Zack Pilien, a Hoʻokuaʻāina intern. “Growing taro is a byproduct.”

A Hawaiian farm that’s regrowing cultural values

Dean and Michele Wilhelm dreamed of creating a space that was restorative and healing for others, perhaps a relaxing retreat for couples or families. They had no intention of becoming taro farmers.

But Mr. Wilhelm started taking the tropical vegetable from their backyard garden to use in his work as a teacher for at-risk youths and incarcerated juveniles. At the same time, the family began cultivating community through gatherings around traditional Hawaiian food. It became clear that taro farming was just the way for the couple to realize their dream.

Now, nearly 10 years after buying land with all the conditions for a successful taro patch, the Wilhelms are carrying out their vision by running Hoʻokuaʻāina, a nonprofit organization. They use taro farming as a means of teaching Hawaiian values and mentoring youths facing challenging circumstances.

“[Dean] tells us that the purpose of the place is to grow people,” says Zack Pilien, a Hoʻokuaʻāina intern. “Growing taro is a byproduct.”

Some researchers have suggested there are links between an erosion of Hawaiian culture, Western influence in the islands, and higher rates of substance abuse, poverty, mental illness, and other social problems among Native Hawaiians. Drug use is particularly prevalent among youths: About 60 percent of Native Hawaiian students have used drugs by 12th grade, compared with 46 percent statewide, according to statistics from the Hawaii State Department of Health.

The Wilhelms hope that instilling Hawaiian values in at-risk youths will help bolster their sense of self-worth and encourage them to be contributing members of society. And taro farming is a fitting vessel for that culture-based mentoring.

Taro, called kalo in the Hawaiian language, is both a root and leafy vegetable. The root can be prepared and served like a potato or in traditional dishes such as poi, and the leaves are often used to wrap fish or pork in a Hawaiian dish called laulau.

But taro is much more than a dietary staple for Hawaiians. The traditional tale of the first kalo plant is also the story of the origins of the Hawaiian people – and the Wilhelms use this narrative to help teach a sense of kuleana, or responsibility.

The story varies, but the gist of it is that a god and goddess have a baby who dies. The first kalo plant grows where they bury that child. Then they have another child who lives and becomes the first human. “This human being cares for its elder sibling, and that elder sibling in turn then cares for that child,” Dean says. “It’s a reciprocal relationship.”

The Wilhelms use the story to discuss the responsibility people have to care for the natural world, and for others. They also talk to those they mentor about a sense of self-respect. “We’re looking to increase positive self-esteem and for them to be able to understand that their life has meaning and purpose,” Mrs. Wilhelm says.

A session in the taro patch

Once a week about a dozen boys who are between 13 and 17 years old join Dean in the mud of the lo’i, or taro patch. The teenagers live at a safe house, called Ke Kama Pono, for at-risk youths.

Dean starts the work session with a Hawaiian proverb, such as “ ‘A‘ohe hana nui ke alu ‘ia,” or “No task is too great when accomplished together by all.” The group discusses how the proverb applies to work in the lo’i or other parts of their lives before jumping into the mud – which is often four feet deep – to weed, harvest, or do whatever is needed that day.

When the teens get tired or act uninterested in the work, Dean strikes the right balance between “stern, direct, and compassionate all at the same time,” says Jared Laufou, direct care counselor at Ke Kama Pono. “His tone of voice is never demeaning, but it’s this kind of tone where he expects you to do your job.”

The boys aren’t used to being entrusted with a project, Mr. Laufou explains. “For a lot of them, they have failed to accomplish something and maybe have been criticized about their failures, so they learned to run away from projects. But working with Uncle Dean at his lo’i, they’re held accountable.”

The Wilhelms see positive changes, such as in the teens’ posture, as they carry themselves with more pride. They also make eye contact more readily, Michele notes.

The changes go beyond the lo’i, Laufou says. As new residents in the safe house realize how their labor at the lo’i can affect the taro, something clicks and they connect that to how their chores help the household function. “I see them actually understanding what hard work is and what it can do, and how it helps more than just themselves but other people around them as well,” he says.

One young man’s story

Wyatt Allen, age 21, says he probably wouldn’t have graduated from high school “if it weren’t for Uncle Dean and going to the lo’i.” He did not live at Ke Kama Pono, but he had struggled in school and skipped class. To engage students like him, a high school teacher decided to try an alternative approach to learning – the Hoʻokuaʻāina mentoring program.

Working in the lo’i taught Mr. Allen perseverance. At times the tasks or the heat would seem too challenging, but he says he learned that “sometimes in life, it’s like that. You want to give up and drop everything, but you can’t. You just have to push through it.”

After Allen graduated from high school, he interned on the farm until he found another job last September.

The Wilhelms’ initial vision grew out of the support they received from their community during a rough patch early in their marriage. “We were crushed and had no hope,” Michele recalls, but people stuck by the couple.

“We were restored” through that support, Dean says. “And once you feel that, you can’t help but want to touch others and restore others as well.”

When they bought the property for the lo’i, it was a tangled rainforest that no developer wanted to touch. Clearing it felt like a never-ending challenge, they say. But looking out at the land, “I could see the taro growing” in my mind, Dean says. “And more importantly, I could see life. I could see people.”

A break from the outside world

Now, going to the taro patch is like leaving the outside world behind for a little while. As one drives down the dirt road to the lo’i, the noise of traffic on the nearby Pali Highway gives way to the sound of the taro leaves rustling in the wind.

Creating that quiet, peaceful space is key in helping the youths let their guard down, Michele says. “We saw these young boys with so much anger and hurt and pain coming with this rugged defense. It takes a couple weeks to get through that, but once they figure out that they can let it down in the mud,” she says, then they start saying things like “I feel so safe” or “I feel at peace.”

The Wilhelms hope that Hoʻokuaʻāina will continue to evolve to include more organizations with individuals who would benefit from the mentoring program. Already the nonprofit has expanded to include weekly community days to bring together people from the area and an internship program to mentor young adults from a variety of backgrounds.

The Wilhelms do sell the taro grown on the farm and hope that the revenue will help pay for the mentoring program in the future. But currently, much of it is funded by grants.

Mr. Pilien, the Hoʻokuaʻāina intern, says it’s hard to put into words the feeling of being at the lo’i, but he doesn’t want to leave.

“I know I can’t be there obtaining this feeling and this experience from Uncle Dean forever,” he says. So he hopes to build a similar program to teach others using farming. Much like the Wilhelms were touched by others’ investment in them, Pilien wants to pass along that feeling.

• For more, visit hookuaaina.org.

How to take action

UniversalGiving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations around the world. All the projects are vetted by UniversalGiving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause. Below are links to three groups aiding young people:

Global Volunteers aims to advance peace, racial reconciliation, and mutual understanding between peoples. Take action: Volunteer in St. Lucia to help change the lives of children in poverty.

Globe Aware has a mission that includes working with children in slums and other disadvantaged youths. Take action: Contribute funds to build a community center in Romania for the Roma.

Seeds of Learning promotes learning in developing communities of Central America while educating volunteers about the region. Take action: Donate money to support students in Nicaragua and El Salvador.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Creating a virtuous circle with North Korea

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

South Korean President Moon Jae-in has announced that he has decided to break what he calls “the vicious circle of military escalation,” with his government offering to hold talks with North Korea. They would be the first since 2015, just before North Korea began rapid advances in missile development. North Korea has a history of agreeing to talks and then merely seeking concessions. So Mr. Moon’s offer does run the risk of rewarding the North’s bad behavior. Yet the alternative, military escalation, could be seen as a greater risk. At the least, the offer may serve as a test of the North Korean regime’s current intentions and its perception of its survival. That alone would be helpful feedback. For now, South Korea should be allowed to see if the virtuous circle – one in which trust and goodwill might allow the two Korean nations to work toward mutual recognition – can replace the vicious.

Creating a virtuous circle with North Korea

With tensions rising over North Korea’s nuclear and missile capabilities, the new president of South Korea, Moon Jae-in, has decided to break what he calls “the vicious circle of military escalation.” On July 17, his government offered to hold talks with North Korea. The purpose is not to negotiate a much-delayed peace deal but seek dialogue over lesser issues. Those include reestablishing a military hotline, joint hosting next year’s Winter Olympics, and resuming the reunion of Korean families separated by the 1950-53 Korean War.

The two sides have not held talks since 2015, or just before North Korea began rapid advances in the firing range of its missiles. Any gradual engagement with North Korea now, Mr. Moon hopes, might lead to a virtuous circle of trust and goodwill that allows the two Korean nations to negotiate the difficult issues of nuclear disarmament and mutual recognition.

Simply imposing more economic sanctions on Pyongyang, he claims, will not be easy to achieve. Instead, a peaceful path to settle the North Korean nuclear issue must be opened. “[T]he need for dialogue is more pressing than ever before,” Moon said in a speech in Berlin in early July.

His offer of talks over minor issues builds on a long tradition of bite-size diplomacy, or what Henry Kissinger has called “the patient accumulation of advantage.” Among diplomats, the notion that virtues such as trust and compassion can create their own self-reinforcing loop and lead to sustaining success is not new. In 1947, US Secretary of State George Marshall proposed using American aid to seed the recovery of a Europe laid flat by war. “The remedy lies in breaking the vicious circle and restoring the confidence of the European people in the economic future of their own countries,” he said.

The idea that initial good steps can build on themselves also has a long history in economics – although economists differ on which measures serve as catalysts to enforce economic progress. In a sign of universal confidence in virtuous circles, the United Nations set specific goals in 2015 that would end poverty by 2030, referring to the goals as “sustainable.”

Moon’s proposal for talks with North Korea also builds on a lesson from history to not let problems fester. As Indian Foreign Secretary Subrahmanyam Jaishankar puts it, “Are we content to react to events or should we be shaping them more, on occasion even driving them?” He cites India’s strategy of seeking good relations with many countries as one of creating “a virtuous cycle where each one drives the other higher.”

North Korea has a long record of agreeing to talks and then merely seeking concessions, such as food aid for its people. Moon’s offer does run the risk of rewarding the North’s bad behavior. Yet the alternative of military escalation and a chance of a devastating war could be seen as a greater risk.

At the least, the offer may serve as a test of the North Korean regime’s current intentions and its perception of its survival. That alone would be helpful feedback. For now, South Korea should be allowed to see if the virtuous can replace the vicious.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

God’s help – always at hand

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By Robert R. MacKusick

During a parade event on a hot and humid day, several soldiers in Robert MacKusick’s military unit fainted. Not wanting anybody else to succumb to the heat, he began praying as he stood at attention. One idea he found especially meaningful was that God is at our “right hand” – we can never be separated from divine Love. Immediately he felt refreshed, and there were no more instances of fainting in his unit. Everyone is capable of feeling Love’s care.

God’s help – always at hand

We were all lined up for a celebration review for the new military post commander. There were thousands of soldiers like me at the event at the army base. Almost summer, the day was hot and humid. And despite the heat, we were still wearing our warm “winter” uniforms.

We all saluted the commanding general. But as the parade progressed, a number of the soldiers in my unit fainted in the heat. I sure didn’t want to faint, and I didn’t want to see anyone else succumb to the heat, either. So, as I stood at attention, I prayed. I remembered these lines from a hymn:

God is my strong salvation;...

Firm in the fight I stand;

What terror can confound me,

With God at my right hand?

(James Montgomery, “Christian Science Hymnal,” No. 77)

The words “with God at my right hand” were especially meaningful to me. In a hand salute, your right hand is next to your face with the tip of your forefinger touching your forehead just above the eyebrow of the right eye.

As I stood saluting, my right hand in that position, it was a symbol to me of how close God is to us. I saw that God, divine Love, could not have been any closer to me, to each one of us, than He was right that very moment – at our “right hand.” The Bible tells us that “God is love” (I John 4:8), and none of us can ever be separated from divine Love. This all-powerful Love is always present, caring for and upholding us, and we can feel it.

Immediately, I felt refreshed and confident that all of us could stand upright for the entire parade event without concern that we would faint in the heat. I could feel God’s love and support and knew it could be felt by everyone. And there were no further instances of fainting in my unit.

In the thick of any kind of battle, we are in fact God’s spiritual children and Love is with everyone right here, right now – always at hand.

This article was adapted from the June 19, 2017, Christian Science Daily Lift podcast and an article in the June 19, 2017, Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Victors, even before they’ve competed

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Please come again: We're working on a story about building friendships across racial lines through “welcome tables” – facilitated discussions between white and black participants.