- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for August 16, 2017

Sometimes the words that might point the way toward a calmer path are there to be heard, if people are willing to listen – and act.

On the global stage this week, China urged a different vocabulary between the United States and North Korea, asking both countries to “hit the brakes on mutual needling,” and “to lower the temperature of the tense situation,” in the interest of getting to diplomacy.

On the regional stage, India and Pakistan each marked 70 years of independence. More than 1 million people died in the chaotic formation of the two countries out of what was British India, and relations remain difficult today. Yet the group Voice of Ram scored a hit on social media this week by blending the national anthems of Pakistan and India into a harmonious message of peace. (It's worth a listen.)

And then the local stage – Charlottesville, Va. The memorial for Heather Heyer, killed when a suspected Nazi sympathizer drove his car into protesters last weekend, took place Wednesday. Here's her mother’s powerful call to action: “You need to find in your heart that small spark of accountability. What can I do to make the world a better place?... Let’s have the uncomfortable dialogue.… We are going to be angry with each other. But channel it not into hate and fear, but into righteous action.”

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

North Korea: What would diplomacy look like now?

After an extended combative exchange between the US and North Korea, many are welcoming what looks like a shift to a more reasoned vocabulary – one that could create a diplomatic opening and progress.

After weeks of US-North Korea brinkmanship, some glimmers suggest that the diplomatic path – though narrowed – remains open. North Korea announced Tuesday that its leader, Kim Jong-un, had decided to hold off on plans to fire ballistic missiles into waters near Guam. In response, early Wednesday President Trump praised Mr. Kim’s “very wise and well reasoned decision.” To be sure, the ups and downs are almost certainly not over – the United States will hold annual joint military exercises with South Korea beginning Aug. 21, potentially provoking the North. “I think we’re on a roller coaster with North Korea, … but we may now be on the downward slope after an especially steep climb,” says Joel Wit, a former State Department North Korea expert who still meets informally with North Korean officials. Among potential diplomatic steps is increasing pressure on China to help defuse the situation. Already, that seems to be yielding results: Beijing supported United Nations sanctions on North Korea, and says it has halted all new imports of coal, iron ore, and lead from the North.

North Korea: What would diplomacy look like now?

For more than two decades, North Korea’s pursuit of nuclear weapons and the missiles to deliver them long distances has prompted recurring international crises.

Sudden bursts of heightened tension, primarily between the North and the United States, were interspersed with diplomacy that never definitively halted the gathering storm.

After a week of brinkmanship and escalating rhetoric between the two sides, Pyongyang and Washington suddenly found themselves at perhaps the most dangerous moment in more than 60 years – with some declaring that the window to anything but a military solution to the crisis had nearly closed.

The ups and downs in tension are almost certainly not over – the US will hold annual joint military exercises with South Korea beginning Aug. 21, a show of force that often provokes the North.

Yet some glimmers suggest that the diplomatic path, though narrowed, remains open. For one thing, North Korea announced Tuesday that its leader, Kim Jong-un, had decided to hold off on plans to fire four intermediate-range ballistic missiles into waters near Guam, the US territory in the Western Pacific. In response, early Wednesday President Trump praised Mr. Kim’s “very wise and well reasoned decision.”

Senior Trump administration officials, including Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, are even hinting that they are looking ahead to what a permanent peace agreement with North Korea might look like – although everyone agrees that getting there remains well in the distance.

“I think we’re on a roller coaster with North Korea, and tensions are going to go up and they’re going to go down, but we may now be on the downward slope after an especially steep climb,” says Joel Wit, a senior fellow at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies’s US-Korea Institute in Washington. “It’s not going to be easy, but if we can keep things from getting out of hand again for a while, we may have at least an opportunity to get somewhere on this” crisis.

Diplomatic pressure on China

The stepping stones on a diplomatic path forward are generally well-marked, although none will be easy, analysts say. Among them: increased pressure on China to move its client-state neighbor away from its threatening posture.

Moreover, the US would likely face its own hard-to-swallow diplomatic prerequisites – for example, accepting the North's denuclearization as a long-term goal rather than as an opening card in any negotiations.

For some, signs are palpable that the diplomatic push with China is already bearing fruit. China has announced it is beginning to implement the new sanctions recently imposed by the United Nations Security Council (including China) on Pyongyang over its recent missile tests. China, which buys more than 90 percent of North Korea’s exports, says it has halted all new imports from the North of coal, iron ore, and lead.

At the same time, the Trump administration appears to have quietly stepped back from plans to curtail Chinese steel imports and from other punitive trade measures.

Still, some North Asia experts say the US will have to do more and push harder to get meaningful cooperation from China on North Korea.

“I guess my response to the Chinese saying they will start enforcing the new UN sanctions is, ‘OK, that’s good, you’re required to,’ ” says Bruce Klingner, a senior research fellow for Northeast Asia at the Heritage Foundation’s Asian Studies Center in Washington. “Are we going to see what we’ve seen in the past, which is that China vows to enforce new resolutions and then backslides after a few months?”

To really get China’s attention, Mr. Klingner says, the Trump administration would have to proceed with a number of “secondary sanctions” on Chinese businesses that continue to work closely with North Korea – for example, banks that launder Pyongyang’s proceeds from its illicit trade in everything from cigarettes and drugs to arms.

“Trump has not yet differentiated his policy from that of [former President Barack] Obama and the former administration’s under-implementation of US laws” that provide for action against Chinese entities using dollars in their dealing with North Korea, he says. “I’m hopeful the administration will live up to its pledges to enforce US law,” he adds, “but until that happens China is not really going to have the incentive to cooperate.”

Others suggest that the US could reinforce pressure on China to get serious by dangling the prospect of Japan going nuclear if the threat North Korea presents to the region is not addressed.

Ground rules for negotiating

As in the past, any serious stab at diplomacy would likely start with what diplomats refer to as “talks about talks” – initial exploration of whether the sides (primarily Pyongyang and Washington) are even able to set the ground rules for negotiations.

Some level of discussions between US and North Korean officials appear to be ongoing. Klingner, a former CIA deputy division chief for Korea, says that while “I’ve been told the [backchannel] is reopened, I would distinguish between diplomacy and negotiations.”

Some aspects of opening positions are already well known – for example, the North Koreans insist that any talks be initiated without preconditions, says Mr. Wit, a former State Department North Korea policy specialist who has continued to meet informally with North Korean officials.

The North balks at US demands that it cease all nuclear and missile testing as a precondition to talks, although it has promoted the idea of “freeze for freeze” – cessation of its tests accompanied by suspension of the US military exercises with South Korea that it considers threatening.

Klingner cautions against such a deal, saying that Pyongyang is equating its own illegal activities – nuclear and missile tests proscribed by UN resolutions – with legitimate activities the US is undertaking with an ally.

“It’s apples and oranges,” Klingner says, adding that a more promising proposal would be for the North to suspend its own military exercises in exchange for a suspension of the US-South Korea exercises it finds threatening. “At least that would be apples and apples,” he says.

On the other hand, Wit says the US should not reject the North’s proposal out of hand, especially since his contacts suggest that the North is not insisting on a freeze of all US military exercises in order to start talking. Rather, he says, Pyongyang would require an end only to those exercises that “are aimed at decapitating the regime.”

That requirement hints at what many experts say is Kim’s sole preoccupation: survival of his regime.

“The North Koreans have built their nukes to ensure regime survival, so they’re never going to give them up voluntarily,” says Vice Admiral John Bird (ret.), former commander of the US Navy’s Seventh fleet in the Pacific, speaking Tuesday in a conference call organized by the Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs in Washington.

“As crazy and wacky and murderous as Kim is,” he says, “I do not believe he is going to cross whatever line he believes would result in a US” attack. “At the end of the day he’s going to be rational on regime survival.”

It is perhaps recognition of Kim’s overriding focus that has prompted Mr. Tillerson to state more than once that the US is not seeking “regime change” or even reunification of the two Koreas, but rather denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.

The hard part will be getting from such statements to the initial steps required before yet another diplomatic initiative aimed at resolving the North Korea standoff could even begin.

Share this article

Link copied.

How ‘Raging Grannies’ are cooling down Portland protests

Wince and walk on by – or maybe even listen because a speaker's prejudices don't target you? In 1943, the US War Department issued a public-service film warning about fascism and the use of prejudice to "cripple a nation." In Portland, Ore., a group of older women are walking straight into the middle of confrontations to help a city stay strong.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

The Raging Grannies, decked out like a Mayberry sewing circle, offer a kind of satirical street theater that challenges authority while charming the public. Lately, they’re having to act as referee between two opposing political extremes, whose violent tactics led Politico to dub Portland, Ore., “the most politically violent city in America.” The model of peaceful protest that has held since the civil rights era is being challenged – not just by the emboldened white supremacists who roiled Charlottesville, Va., but also left-wing anarchists. “We’re struggling with our role,” admits Granny Linda Schmoldt. “[W]e’re having to say, amid all this punching and rolling in the streets, ‘You have to stop right now and go to your corners. Be nice to each other.’ ” The growing frequency of actual street fighting, says political scientist Michael Heaney, is notable, including deadly serious incidents such as Charlottesville and the targeting of Republican congressmen at baseball practice. Longtime civil rights protesters, like the Grannies, say they are dismayed by the left fringe’s embrace of violence. While punching Nazis may be a popular internet meme, they argue, the answer to hatred cannot be more hate. “Our message right now is, Don’t hurt people to be peaceful,” says Granny Diana Richardson. “We have to realize we’re part of a huge community, which is the whole world.”

How ‘Raging Grannies’ are cooling down Portland protests

Amid the hubbub of Portland’s waterfront “Saturday Market,” song suddenly erupts from what looks like a Mayberry sewing circle, their raised fists punctuating the chorus: “It is a time to care, not to kill....”

The singers’ dresses and hats are mismatched, their song a tad out of tune, but they are, Portlanders say, ever so endearing: Twenty-odd older ladies in hats, outsized glasses, and gingham dresses, belting out protest lyrics set to standards – and sometimes set to dance. One has little cherries hanging off her hat, while others don faded “ERA” pins.

One of the most beloved social activist groups in this Pacific Northwest city, they are the Raging Grannies. “Grannying is the least understood and most powerful weapon we have,” writes Granny Rose de Shaw on the national blog. And in a time when peaceful protest is increasingly giving way to fistfights, clubs, and chemical spray, their humorous message may be more important than ever.

The Grannies offer a kind of satirical street theater that challenges authority while charming the public – but lately, they’re having to act as referee between two opposing political extremes, whose violent tactics led Politico to dub Portland “the most politically violent city in America.”

As cities such as Berkeley, Calif., and Seattle have become epicenters of rolling street fights fueled by intense partisanship, the model of peaceful protest that has held since the civil rights era is being challenged – not just by the emboldened neo-Nazis and white supremacists who roiled Charlottesville, Va., over the weekend, but also left-wing anarchists. Here in Portland, both sides’ tactics of physical confrontation have begun to scrape away at the city’s peaceful image.

“We’re struggling with our role,” admits Granny Linda Schmoldt, a retired librarian. “The difference for us now is we’re having to say, amid all this punching and rolling in the streets, ‘You have to stop right now and go to your corners. Be nice to each other.’”

In a new tactic, experts say, the white nationalist movement is targeting progressive cities, calling leftist activists out on their own turf. And for its part, the antifa (short for anti-fascists) movement has embraced violence as a tactic against what it sees as creeping fascism on American streets. The ensuing clashes have rattled residents. In late May, a participant in an alt-right rally stabbed to death two Good Samaritans, and wounded a third, who were coming to the aid of two minority women on the city’s light rail train. The deaths sparked shock and mourning, and then a wave of counter-protests that often have devolved into violence.

The situation has put Portland at the epicenter of what some call a soft civil war of fists and sticks "for control of America's streets," as National Review essayist David French writes.

According to University of Michigan political scientist Michael Heaney, only about 3 percent of protest attendees, who tend to be more politically active, say violence is “very” necessary to make a point. (Only 1 percent of the general population makes that claim.)

Notably, he says, that number has not shifted since President Trump’s election, suggesting that Americans are not growing more accepting of political violence in the streets. Indeed, since the 1980s, says Rachel Einwohner, a political scientist at Purdue University, Americans have increasingly come to see nonviolent protests as not only legitimate but necessary for democracy. And so far, most Trump era marches, including the women’s march and Mr. Trump’s campaign-style rallies, have remained peaceful.

Yet the growing frequency of actual street fighting in liberal strongholds like Portland and Berkeley, Calif., says Mr. Heaney, is notable, since the upshot is that America is witnessing a sum total of more political violence, including deadly serious incidents such as the weekend of violence in Charlottesville, Va., that left three dead and several dozen injured, and the targeting of Republican congressmen at a baseball practice this year. The nature of the violence, too, he says, is different.

“This is really ideological and partisan violence … [not] violence in response to very concrete issues,” says Heaney, the co-author, with Fabio Rojas, of “Party in the Street: The Antiwar Movement and the Democratic Party after 9/11.” “People are clashing now because they see the world in a different way ideologically – and they detest the beliefs that the others have about the world. We have two camps in our society that are not communicating civilly any more. This violence … is one manifestation of that decline in civility.”

Turning down the temperature

Progressive organizers say they are seeing several shifts in response to the stubborn street battles, as people try to turn the emotional temperature down. The Grannies may be the most colorful – if not the most quirky.

The blue-vested Portland Peace Team has seen applications skyrocket since the MAX train stabbings. Progressives in Berkeley have utilized a tactic of empathy tents at rallies, offering 10 minutes of nonjudgmental listening to help ease tensions. Organizers in Portland are being trained as “vibe-watchers” to look out for brewing trouble.

Native American groups, too, have urged peace to bring antifa and the self-described alt-right back from the brink of battle.

Part of the message is getting through. One antifa group, Rose City Antifa, said they would stay away from a July protest, choosing instead to do a fundraiser.

At the same time, mainstream organizers are struggling to persuade the antifa flank that violent tactics are counterproductive. Instead, antifa, who often hide their faces to avoid legal repercussions, have accused the Portland Peace Team of trying to unmask them.

For her part, Granny Denise Busch, she of the cherry hat, says she has been treated warmly by antifa protesters. In turn, she has engaged some of the hooded anarchists with pleas to not fight, some of which, she said, seems to have worked.

“We become idealized grannies to them, and they don’t want to disappoint us,” she says.

Or, as Portland resident Tom Hastings says, “It’s very, very hard to go making nasty, rotten claims about a granny.”

Long-time civil rights protesters, like the Grannies, say they are dismayed by the left fringe’s embrace of violence. While punching Nazis may be a popular internet meme, they argue, the answer to hatred cannot be more hate, and peace movements shouldn’t be in the business of hurting people.

“Movement leaders sort of agree to what is known as a diversity of tactics, but my question now is: Do you want diversity of tactics or do you want diversity of people?” says Mr. Hastings, a Portland State University professor and a veteran of Portland’s so-called nonviolent army. “If there’s a violent flank in a movement, your recruitment numbers go down, which correlates with a much lower chance of succeeding with your announced goal.

“Therefore, God bless the Grannies.”

Rocking chair rallies

The Raging Grannies were founded in Victoria, British Columbia, in 1987. A satirical temperance-style union, they cite “a history of trouble-raising when not listened to,” as Ms. de Shaw wrote on the group's web page. “Even in our times, we grannies have raised a few mountains, caused a few floods.”

Requirements to be a Granny are: being at least 55, and a “willingness to make noise” tempered by “an open heart to learn something new.” “No singing ability” and “no color sense, obviously,” are required, writes de Shaw.

Since Trump’s election, the Portland Raging Grannies’ ranks have almost doubled, to 55. Their oldest member is well into her 80s. They employ a strategy exemplified by the Otpor ("resistance") movement in Serbia, which helped undermine political and law enforcement support for strongman Slobodan Milosevic through humor, satire, and street theater.

They are also not beyond civil disobedience. Grannies have been arrested during events held by the North Carolina protest movement known as “Moral Mondays.” And a hero of the national group tied her rocking chair to a train track to protest a planned oil rig. She calmly knitted a sweater until police arrested her.

In 5-1/2 years of existence, the Portland Grannies have fine-tuned similar tactics, sometimes to great effect.

“They went to a military recruiting center, a place where I’d been doing candlelight vigils for a year, and they were very gung-ho,” says Hastings, the veteran anti-war organizer. “They put a whole bunch of rocking chairs in front of this recruitment center – a rocking chair blockade. When police came, they warned the Grannies. The Grannies took off but left their chairs, so the police had to load up the chairs. The picture in the paper: Police arrest grandma’s rocking chair.”

The Grannies “show people what it means to be an activist, and in that way it highlights something else that social movements do: They sort of provide therapy for disaffected people,” adds Purdue’s Ms. Einwohner, who studies the dynamics of protest and resistance.

Portland's protest history

Portland has a long history of protest – 40,000 protested the decision by President George W. Bush to invade Iraq in 2003; a decade earlier, President George H.W. Bush’s Secret Service nicknamed the city “Little Beirut” for its raucous anti-war protests.

“What’s happening in Portland is really just the latest chapter of an old story – sort of the frontier spirit where the margins are celebrated and where to be a registered Democrat is something of a stodgy, boring position to take,” says Randy Blazak, who studies hate movements at Portland State University. “There are probably more anarchists out admitting their political position than dyed-in-the-wool traditional Democrats. May Day is the biggest holiday in the city, much bigger than Christmas.”

The roots of the current conflict can be found in the skinhead wars of the 1980s and ’90s, when punks-turned-antifascist rumblers took on similarly attired neo-Nazi skinheads after the 1988 beating death of an Ethiopian college student by white supremacists. Then as now, antifa would look for tattoos or jewelry that suggested Nazi sympathies – and then attack – verbally or physically.

Alexander Reid Ross, author of “Against the Fascist Creep,” told Portland’s Willamette Weekly earlier this year that antifa – in his view, rightly – understands that “the alt-right has to be understood as a fascist movement.”

Their opponents include rally organizer Joey Gibson, who advocates for free speech rights for conservatives. While Mr. Gibson says he does not welcome white supremacists, some regular attendees admit that part of their mission is to defend themselves – and their cause – by “kicking some antifa [butt],” as Tiny Toese, a self-styled Samoan patriot who was arrested after a brawl in July, told followers on social media.

The stated aim of that Sunday’s “Patriot Prayer” rally was to accuse antifa of domestic terrorism by using tactics to hurt conservatives, including calling their bosses to inform them of their political activities. The focus on leftist agitators is part of a deeper political shift, as well. Under Attorney General Jeff Sessions, the Department of Justice has disbanded a unit on right-wing extremism and is now monitoring Portland and other cities for evidence of “domestic terrorism” from the left.

“We’re seeing kind of the children of [the skinhead wars],” says veteran Portland organizer Jamie Partridge. “The Proud Boys are the street fighters who aren’t really that ideological, but they are mad as hell. They see in Donald Trump a beacon of hope for bringing back the America that they think once was, but that they’ve never known.”

'Don't hurt people to be peaceful'

There are growing concerns among organizers like Mr. Partridge that the self-described alt-right, despite its embrace of white nationalism and white supremacy, is having success in recruiting as a result of the attacks from antifa. The addition of Oath Keepers, a national group of retired law enforcement, as volunteer security has helped give the “Patriot Prayer” movement legitimacy in broader conservative circles.

“The thing about the left, we tend to be Chicken Littles: ‘Oh, this is Hitlerian,’” says Hastings. “We tend to default straight to the bottom of the slippery slope, so our credibility has been radically compromised. Yes, there are spooky parallels between what Trump is doing and what Hitler did. But antifa can’t operate with violence and expect it to produce anything other than a [backlash] in the general population.”

It also is having an impact on rally attendance. On that Sunday, noticeably fewer activists on both sides showed up for dueling rallies before the fighting began, only to quickly dissipate.

Fredric Alan Maxwell, a Portland writer and activist, stayed home from that event with his cat. At an earlier melee, he was left slumped and scratched up after a group of antifa swept past him. Afterward, he wrote that his attackers were “hiding their faces under bandannas as though robbing not speech but a stage….”

Such decisions by longtime peace activists to stay home, as much as the fighting itself, is driving the transformation of protest in the Trump era, including for the Raging Grannies.

In response, the Grannies have adjusted their clothing policy, replacing at times their traditional dresses and hats for black T-shirts for mourning and white T-shirts with sashes for observing rallies – and engaging with edgy young protesters.

“Our message right now is: Don’t hurt people to be peaceful,” says Granny Diana Richardson. “Instead, rally the troops by naming what is wrong. We have to realize we’re part of a huge community, which is the whole world.”

Correction: The rocking chair blockade was conducted by the Seriously Pissed Off Grannies.

Etsy faces a test over doing well while doing good

It might not seem like a daring proposition, but it is: a company's quest to meet the demands of shareholders while holding to its ethical values.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In 2015, Etsy was a fast-rising community of online artisans offering everything from jewelry to pillows. Annual sales had reached $2 billion. The company was going public with a stock offering, but also hewing to a sense of higher mission. “We don’t believe that people and profit are mutually exclusive,” CEO Chad Dickerson wrote. Now that premise is being tested. On Aug. 3, Etsy reported its second quarterly profit since going public. For some shareholders, progress isn’t fast enough. Mr. Dickerson was ousted in May after a hedge fund lobbied the board to cut staff and consider selling the company. Etsy’s bumpy road raises the question: Is Wall Street open to do-gooder companies that don’t put shareholders first? If not, those firms may need to rely on private equity, not public stock, in their bid to become a bigger part of the business ecosystem.

Etsy faces a test over doing well while doing good

As a software engineer at Etsy, the online crafts marketplace, Kiron Roy wasn’t in the habit of dialing into management’s quarterly earnings call with analysts. But when the company’s new CEO held his first earnings call on Aug. 3, three months after his predecessor was abruptly fired for not making enough money, Mr. Roy was all ears.

From a financial stance, the news was good: Etsy reported a quarterly profit, only its second since it went public in 2015. Analysts were assured that the company was in better shape after cutting 23 percent of its workforce in May and June and focusing more on marketing and payments. The share price duly rallied and has since hit a yearly high.

But where were the social and environmental values that Etsy was supposed to embody, the idea that people come before profits? Roy didn’t hear them. “We have kind of set aside those values in the interest of pursuing short-term gains in order to appease Wall Street,” he says.

At most listed companies, such criticism might be considered jejune. But Etsy has prided itself on being different, part of a new wave of ethical enterprises that want to rewrite the rules of capitalism. Its apparent retreat in the face of shareholder pressure has raised doubts over both the viability of its model and the broader challenge for socially responsible companies that go public.

Simply put, is Wall Street open to do-gooder companies that don’t put shareholders first?

Perhaps not. Even investors who look for start-ups that promise long-term, sustainable growth say that it’s a tough sell in stock markets that are driven by short-term profits. That caps the growth potential for ethical companies, given that most equity capital goes into public markets.

Solar panels, composting, and parental leave can animate employees and build customer goodwill. But when it comes to corporate finances, what fund managers see are the bottom-line costs, says Matthew Weatherley-White, managing director of the CAPROCK Group, a wealth management company based in Boise, Idaho, that has invested in ethical companies.

“I think the public markets aren’t ready yet,” he says. “There’s no mechanism to discount the future value [of a stock] based on non-financial metrics.”

Rise of the B Corps

Still, even as Etsy stumbles, other companies with similar missions are raising capital from hard-nosed investors, says Rick Alexander, a corporate lawyer in Wilmington, Del., who works at B Lab, a nonprofit that certifies ethical companies, including Etsy. Others include Patagonia, Warby Parker, Ben & Jerry’s, and Kickstarter; most are small and medium-size enterprises.

Known as B Corporations, such companies must undergo audits of their environmental and social practices and, when possible, convert into a public-benefit corporation, an entity recognized in 35 states. By doing so, firms legally mandate managers to consider the interests of all stakeholders, from suppliers to employees, as well as the environment, and not just profit-hungry shareholders.

In February, Laureate Education, a for-profit college company that is registered in Delaware as a public-benefit corporation, raised $490 million in an initial public offering. “They didn’t get a single question on their [pre-IPO] roadshow about being a benefit corporation,” says Mr. Alexander.

Other privately held “B Corps” have raised money from venture capitalists who like their business plan, even if they don’t fully embrace the idea that other stakeholders matter equally, he says.

“Ultimately stockholders have to understand and believe that there’s a better way for businesses to be run for their long-term interest. And if they don’t believe that, then none of it works because they’ve got the money,” Alexander says.

When Roy joined Etsy in 2014, the hand-crafted shoe was on the other foot. Funders were lining up to invest in a growing community of small merchants selling cute bags and one-of-a-kind jewelry. By early 2015, when Goldman Sachs was preparing its stock offering, Etsy could point to nearly $2 billion in sales, double what it had two years earlier.

'Etsy can be a model'

The company could also point to its ethical standards – and it did, adding that this mission would continue. “We don’t believe that people and profit are mutually exclusive,” then-CEO Chad Dickerson wrote in 2015. “We believe that Etsy can be a model for other public companies by operating a values-driven and human-centered business while benefiting people.”

Roy says these standards helped to make Etsy a rewarding place to work, along with the perks that it offers. He works at the firm’s headquarters in Brooklyn, an airy expanse of reclaimed wood and recycled water where food waste is composted and yoga spaces abound.

“The public commitment [to ethical values] allows you to bring in people who want to work at Etsy for less than they would get at another place that doesn’t care about the environment and other social goods,” he says.

The firm’s fancy digs and its benefits policy – six months parental leave – have run into criticism. Mr. Dickerson was ousted in May after a hedge fund lobbied the board to cut costs, slash headcount, and consider selling the company to the highest bidder. Some have drawn parallels with Whole Foods, the grocery chain with its own brand of “conscious capitalism” that was sold to Amazon in June after a similar campaign by activist shareholders.

The turmoil at Etsy jolted Roy, who this month launched a public petition urging the board and management to respect the company’s ethical mission and keep employees better informed. It has more than 150 signatures, including from Etsy sellers and other interested parties, he says.

Roy acknowledges that an earnings call with analysts is about numbers, not values; he also says he was cheered to hear the renewed focus on revenue growth and new opportunities, since he wants to Etsy to succeed. Still, what worries him and other petition signers is that the firm may dilute its social responsibilities – its plan to convert into a public-benefit corporation has been put on hold – as it concentrates on raising its stock price.

This is a reasonable fear in a cost-cutting scenario, says Mr. Weatherley-White, whose firm (also a B Corp) manages about $3 billion in assets. “There is a cost associated with social responsibility,” he says. This doesn’t mean that companies shouldn’t stick to their missions, but they face a tension as they grow larger and look for efficiencies.

Better to stay private?

To some mission-driven entrepreneurs, this is an argument for staying private. “If you want to take on the devil, go on and do it. Investors aren’t the only way to get money,” says Thomas Kemper, who runs Blue Dolphin, an eco-friendly office supplies retailer in Dallas.

Mr. Kemper founded his company in 1993 with $60,000 in capital. He has reinvested its profits and not raised money that comes with strings attached. Blue Dolphin is a B Corp, and like most it remains relatively small. “I don’t think we’re self-limiting. We don’t want to exceed what we think is a reasonable path for our company,” he says.

To be sure, selling shares to the public isn’t the only end goal for ethical startups.

Some have sold themselves to public companies that wanted their brand and mission. Ben & Jerry’s, the ice-cream maker, is a subsidiary of Unilever, a Dutch-Anglo food giant. Danone, a French multinational, bought Happy Family, an organic baby-food startup, in 2013, after the company turned down other investors who didn’t share its social mission.

Warby Parker, an eyewear firm that donates a pair of glasses to the needy for each one sold to the public, has raised over $200 million in venture capital but so far not filed for an IPO.

How Etsy navigates the cross-currents of shareholder pressure and ethical values will be closely watched. As an early B Corp to go public, it remains a touchstone for a broader movement. But it’s also a cautionary tale about the need to keep an eye on fundamentals.

“I wouldn’t be in business if I didn’t show a profit. If we’re not making a profit, we’re not here,” says Kemper.

[Editor's note: The article's penultimate paragraph was corrected to reflect that another B Corp went public in the US before Etsy.]

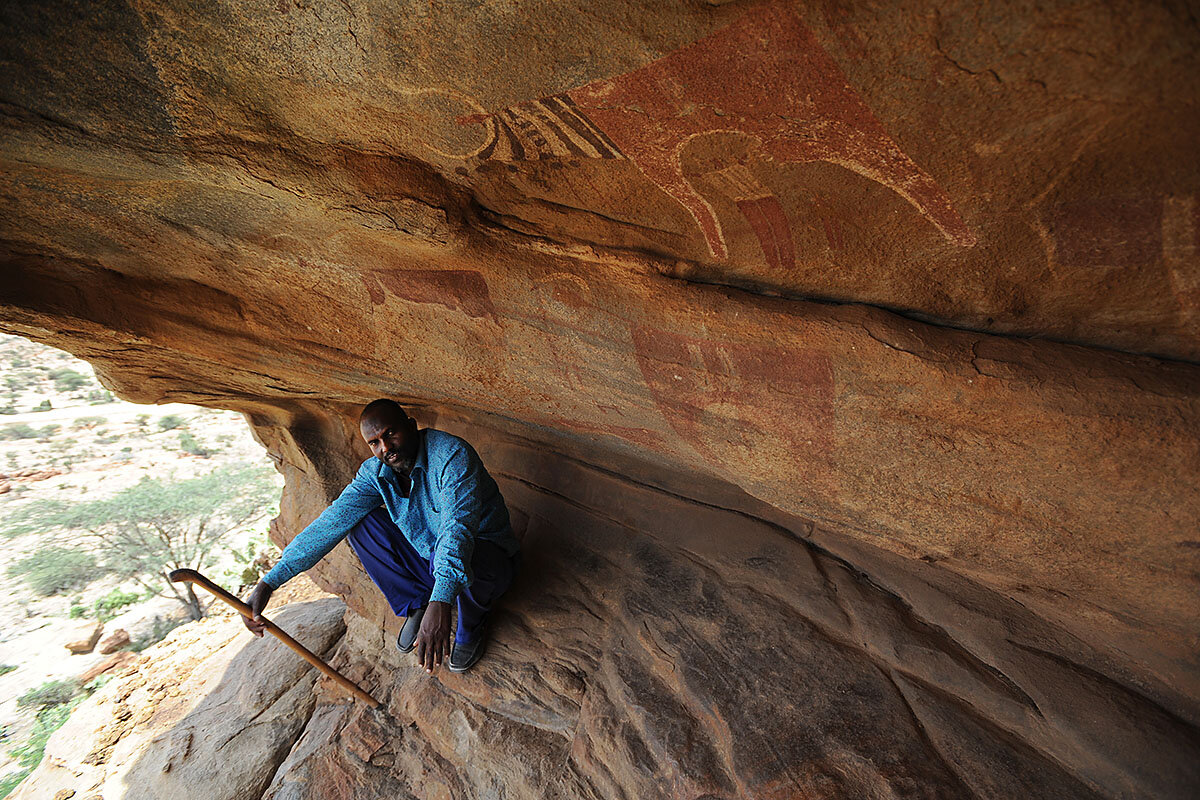

Saving history and heritage in disputed Somaliland

Somaliland's ancient cave art is a world treasure – witness the drive for World Heritage status. But Somaliland is not recognized as a country by the world. How do you protect history and heritage in disputed territories?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Five thousand years ago, painters brushed vivid scenes across this rock outcropping in the Somali desert: hunters with bows and arrows; long-horned cattle, antelope, giraffes, and elephants. Local tradition held that the site was haunted, so although Musa Abdi Jama knew where it was, he’d never looked up close. In 2002, when French archaeologists asked him for directions, he merely pointed them in the right direction. But the next day – after the research team had become the first to “discover” the art – he says he received a call from the president of Somaliland, this breakaway region that declared independence in 1991. “You are responsible for this area,” the president said. Today, Mr. Jama is the caretaker for the Laas Geel paintings. But getting international recognition, such as UNESCO World Heritage status for the sites, is challenging because of Somaliland’s ambiguous political status: No other country recognizes it. And that recognition, advocates say, would help preserve the site. "It’s like going to a gallery in France or New York,” says one Somali anthropologist. “We want to protect it.”

Saving history and heritage in disputed Somaliland

Hidden in the Somali desert, beneath stunning, ancient rock cave paintings, the thin trail of a snake traces a winding line across the dust. A few strands of once-protective barbed wire are pushed to the side; goat tracks abound.

Somaliland’s most prized archaeological treasures – which locals fearfully called “the place of the devils” for centuries – could not be more remote.

Exposed to the elements, the colors have changed since caretaker Musa Abdi Jama first saw them at a distance in 1969. Back then, everyone in the local villages thought the place was haunted. No one visited.

Today, the aging pastoralist laughs at the memory of the myths he heard about the place as a child – passed on to him as they were from one generation to the next around dinnertime family campfires.

“We believed it was drawn by the devil with blood,” he says, “and believed that when we slaughtered a goat for protection, the devil would come and suck the blood from the sand.”

The uniformed Mr. Jama uses a cane to point out features of the Neolithic paintings: the hunters with bows and arrows; long-horned cattle, antelope, giraffes, and elephants; and women giving water to a dog – being “more kind” than the hunters, he says.

Striking in their red and dun colors and more than 5,000 years old, the cave paintings are tucked away in the overhangs of a nondescript rock outcropping. The cave lies at the end of a miles-long track across inhospitable desert, 40 miles northeast of Hargeisa, the capital of the remote Horn of Africa nation of Somaliland – a de facto state that declared independence from Somalia in 1991. The nation, whose territory was once a British colony, has remained largely peaceful, even as the rump Somalia state to the south has been torn by conflict for decades.

But Somaliland remains internationally unrecognized – and that ambiguous political status is a key difficulty preventing Laas Geel paintings and other Somali treasures from being listed as a United Nations World Heritage site, which would provide a major boost in protecting and promoting this historical heritage.

Universal value?

To be added to UNESCO's World Heritage list, a site must be of “outstanding universal value” and meet at least one of 10 criteria. Somaliland’s rock art appears to meet at least two of those, including bearing “a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living or which has disappeared.”

A listing would provide new protections, along with prestige on par with the more-famous paintings in France’s Lascaux or Spain’s Altamira caves.

Yet the Somalia government in Mogadishu has yet to ratify UNESCO's 1972 World Heritage Convention – despite registering intent to do so last year. No Somali site was included in the 21 new cultural sites designated in early July when the World Heritage Commission met in Krakow, Poland.

The new designations include caves and Ice Age art in the Swabian Jura mountains in Germany, and three sites in Africa, including Eritrea, Angola, and South Africa.

Official recognition and protection status is required by UNESCO if sites such as Laas Geel are to be preserved, says Saad Ali Shire, the foreign minister of Somaliland.

“It’s not just important to Somaliland; it’s a global heritage. It belongs to me as much as it belongs to you,” says Dr. Shire. “If we lose it, it’s not just a loss to Somaliland, but a loss to everyone.”

A visit to Laas Geel

Today, when caretaker Jama speaks about protection at Laas Geel, he is not speaking about a fear of demons. Instead, he worries about deterioration of a site that could attract visitors and put Somaliland on the archaeological map.

The day after Jama pointed a French archaeological team to the site in 2002 – the first outsiders to “discover” the caves, and date them to 5,000 years old – he says he received a surprise message from the Somaliland president, telling him: “You are responsible for this area.”

Honored by the request, Jama had to overcome his nervousness after a lifetime of hearing the stories. The next day was his first time to actually visit the cluster of caves and their rich paintings up close.

These days, a sign warns visitors about the fragility of the ancient art, instructing that they not be touched. But there is little else protecting the site except a single metal bar across the rocky road leading to the outcroppings.

Several UNESCO teams have visited, officials here say, but every bid to add the site to a global list has been thwarted by the fact that neither the United Nations nor any country recognizes Somaliland.

History rubbed away

Shire advocates for UNESCO recognition at Laas Geel, but also notes that more than 100 sites of historical importance have been identified in Somaliland, including cave paintings, centuries-old cities and ports, and ancient cemeteries. “We need to have a strategy to preserve this and other sites, and also do some exploration,” he says. “There is a lot of valuable heritage to be discovered.”

Those words are echoed by Somali anthropologist Najib Shunuf, who has studied the rock art and advocates for its wider recognition.

“It’s one of the rarest places in the world, where you can find such a very well decorated place. We are lucky to have something of that standard in Somaliland [that] looks like it was painted two years ago. It’s like going to a gallery in France or New York,” says Mr. Shunuf.

“There are already some deterioration of the colors, [and] many tourists going there with no knowledge,” says Shunuf. “People are touching it, people are sitting on it, and using flash photography, which can damage it in the long run.”

Cracks in the walls let in dirt and water, causing further damage, he adds. Some harm has even come from amateur archaeologists, who have scratched some paintings with knives.

Back at the rock caves, Jama points out how a layer of dust has obscured some of the images. Some grit is shaped in the form of rivulets, from water that once trickled here.

“It’s different from the day it was discovered; then it was bright colors, but not now,” says Jama. During a recent visit from the French team that first brought the art to world attention 15 years ago, “they were surprised because they knew it [then] was very colorful,” he says.

Jama shows where a protective wall had once been built. But today, the ancient paintings face the desert, exposed at their high perches along the rock outcropping.

“The rain, the wind and the dust can wash it out,” says Jama. “It needs more protection.”

Blowing the whistle on a decline in women coaches

As barriers for female athletes have fallen, those for female coaches have risen. Changing that trend requires exposing hidden obstacles and challenging long-standing prejudices.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Title IX, the gender-equity law that celebrated its 45th anniversary this summer, has come to be synonymous with the advancement of women’s athletic opportunities. But that’s only partly true. As the number of women athletes has swelled sixfold, and women’s sports have become more competitive, the percentage of women coaching those teams has dropped from 90 percent to less than half. Sometimes athletic directors, such as Joe Sterrett at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania, have few qualified women apply for head coaching jobs – especially in sports like soccer and volleyball. But he and several coaches interviewed by the Monitor are working to address the factors that have caused the decline, from gender bias in hiring to lack of professional development opportunities. “It matters a lot for girls, but it’s also important for young boys,” says Nicole LaVoi, co-director of Tucker Center for Research on Girls and Women in Sport in Minneapolis. Less than 3 percent of NCAA men’s teams are led by female coaches. “We need boys to view and perceive and value women leaders as well,” she adds. “And when they have a [female] coach, that’s one way we can do that.”

Blowing the whistle on a decline in women coaches

As a synchronized swimmer in college, Kathy Delaney-Smith did not seem destined to become Harvard’s star women’s basketball coach.

When she interviewed for a swim coach position in Boston’s southwestern suburbs back in the early 1970s, the superintendent asked if she could also coach their basketball team. “And I'm like, ‘Yes, of course I can,’ ” she recalls, despite having only played on an informal team – coached by her mom – where the girls played six-on-six and didn’t even dribble. “I don’t know where that came from.… I didn’t know anything about anything, but I really wanted the job.”

The first year, her basketball squad went 0-11.

So she read books, went to clinics, and built a team that went undefeated for six seasons. That brought a Harvard recruiter to her door. Since saying yes 35 years ago, she has become the winningest head coach in Ivy League history, with 567 career wins and 330 Ivy League victories. That’s more than any other coach – men’s or women’s – in the entire Ivy League.

Now Delaney-Smith is on the forefront of a different challenge, one in some ways brought on by the success of women’s sports. The ranks of female collegiate athletes have grown sixfold since Title IX, the 1972 law promoting gender equality in education. But paradoxically, as women’s sports became more competitive, the percentage of teams coached by women has dropped from 90 percent to less than half.

“You see this everywhere in the economy, 80 percent of leadership positions go to men,” says David Berri, co-author of “The Wages of Wins: Taking Measure of the Many Myths in Modern Sport.” “[Recruiters] interview people, but in the end, they settle on what they had before and what they feel comfortable with.”

Correcting that imbalance is proving difficult, in part because the dearth of women coaches discourages others from joining their ranks. But Delaney-Smith and others are working to address the factors that have caused the decline, from gender bias in hiring to lack of professional development opportunities to an increasingly demanding competition and travel schedule that interferes with work-life balance for those with young children.

If successful, their efforts could not only encourage and empower more women to join the leadership ranks of collegiate athletics, but also have a snowball effect by inspiring others to follow suit.

“We know from the data that girls and women coached by women are more likely to go into coaching,” says Nicole LaVoi, co-director of Tucker Center for Research on Girls and Women in Sport in Minneapolis. “If we don’t have any women coaching, it’s less likely we’ll have more girls and women going into coaching themselves.”

4 in 10 women report gender bias in hiring

Since the early days of Title IX, which celebrated its 45th anniversary in June, the number of female athletes at NCAA schools has increased from less than 30,000 to more than 193,000, according to the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA).

But women hold less than 23 percent of all coaching positions in NCAA sports. And within this pool, more than 40 percent of female coaches said they were discriminated against during the hiring process because of their gender, according to a 2016 report from the Women's Sports Foundation. Among all NCAA coaches – both male and female – about 65 percent felt it was easier for men than women to land the top-level coaching jobs.

Joe Sterrett, athletic director at Pennsylvania’s Lehigh University, says in his past two searches for head coaches – in field hockey and women’s golf – there were strong female candidates, and both hires ended up being women.

Going back five or six years, he also had openings for head coach positions in women’s volleyball and soccer, and ended up selecting men – “primarily because they were considerably more qualified in terms of experience than our strongest female candidates,” explains Sterrett, who has been athletic director for close to three decades. “Every search I have done in those two sports during my tenure has produced an applicant list that is heavily skewed to males.”

Ashley Phillips, a former goalkeeper for the professional Boston Breakers soccer team, admits it can be somewhat intimidating for many women to get into the coaching world.

The new head coach of women’s soccer at Northeastern University in Boston, she recently attended a seminar where she was one of only three women out of 28 coaches. “You have to … let things run off your shoulders or you could get eaten alive in a profession like this,” says Phillips.

She may have had an easier path than others to her current role. As an assistant coach, she was mentored by Tracey Leone, who stepped down in 2016 after six years as head coach. Before that, Leone coached Phillips as she came up through Boston Breakers Youth Academy, one of two national feeder programs leading into the women’s professional league.

“She showed me that it’s just as easy for a woman to take this all on as it is for a man,” says Phillips.

But LaVoi of the Tucker Center says that athletic departments should do more to adopt family-friendly policies, such as providing money for partners or caretakers to travel with women who have young children. She mentions the Alliance of Women Coaches, which started five years ago, as one organization working to change policies and provide support for female coaches – especially as women’s sports have become more competitive, and the commitment required of coaches has escalated.

“Where do you stop being a coach and when do you start having a life?” asks Nancy Feldman, head coach of Boston University’s soccer team, who was the school’s first female soccer coach when she was hired in 1995. “It becomes hard to have balance professionally because of the demands, expectations, and competitiveness of the sport.”

Why it's good for male athletes, too

Despite such challenges, however, the turnover rate of head coach positions at NCAA Division-I institutions this past year was only 7.6 percent – similar to the past several years, according to a recent study by the Tucker Center and the Alliance of Women Coaches. The low turnover rate suggests that once women begin coaching, they tend to stay. The challenge is getting them there in the first place.

Sterrett, the athletic director at Lehigh, says one of the most effective recruiting strategies is cultivating graduating athletes. Four of the school’s current head women’s coaches previously served as assistants or graduate assistants.

“We have worked hard to provide an environment in which they feel supported, have flexibility in the way they manage their jobs, and they have been able to integrate family with career,” says Sterrett. “Beyond ‘growing our own,’ there are very good women out there, or among most staffs, and those women need an opportunity to develop and to be supported in their development.”

Experts say achieving greater gender equity in the coaching ranks would benefit not only women, but society as a whole.

“It matters a lot for girls, but it’s also important for young boys,” says LaVoi. Less than 3 percent of NCAA men’s teams are led by female coaches.

“We need boys to view and perceive and value women leaders as well,” she adds. “And when they have a [female] coach, that’s one way we can do that.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Solar eclipses as lessons in lifting shadows of hate

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

The United States now seems as much under a shadow of hatefulness as it will be Monday under the darkness of the moon’s shadow from Oregon to South Carolina during the total solar eclipse. This dark mood may seem as permanent as was depicted in ancient myths about an eclipsed sun never returning. Humanity has been liberated from false beliefs about the motions of the stars and planets. Is there a similar lightness of understanding to lift America’s dark mood of hate? Lifting this gloom will take individual acts of faith that the natural affection among diverse people can return to the American landscape. That includes acts like the Charlottesville Clergy Collective’s opening of a worship service on that day of that Virginia city’s rally to help bring calm to the event. Such moments of courage, understanding, and love are not as easily measured as acts of hate. Yet they are more real and eternal.

Solar eclipses as lessons in lifting shadows of hate

During a total solar eclipse in 1988, a remote tribe in the Philippines called the Tboli did what it had done for centuries during previous eclipses. The people rushed to make loud noises by banging gongs and drums. Despite some modern education in astronomical science, about half the tribe still believed an ancient myth that the sun might not shine again unless they made the clanging sounds.

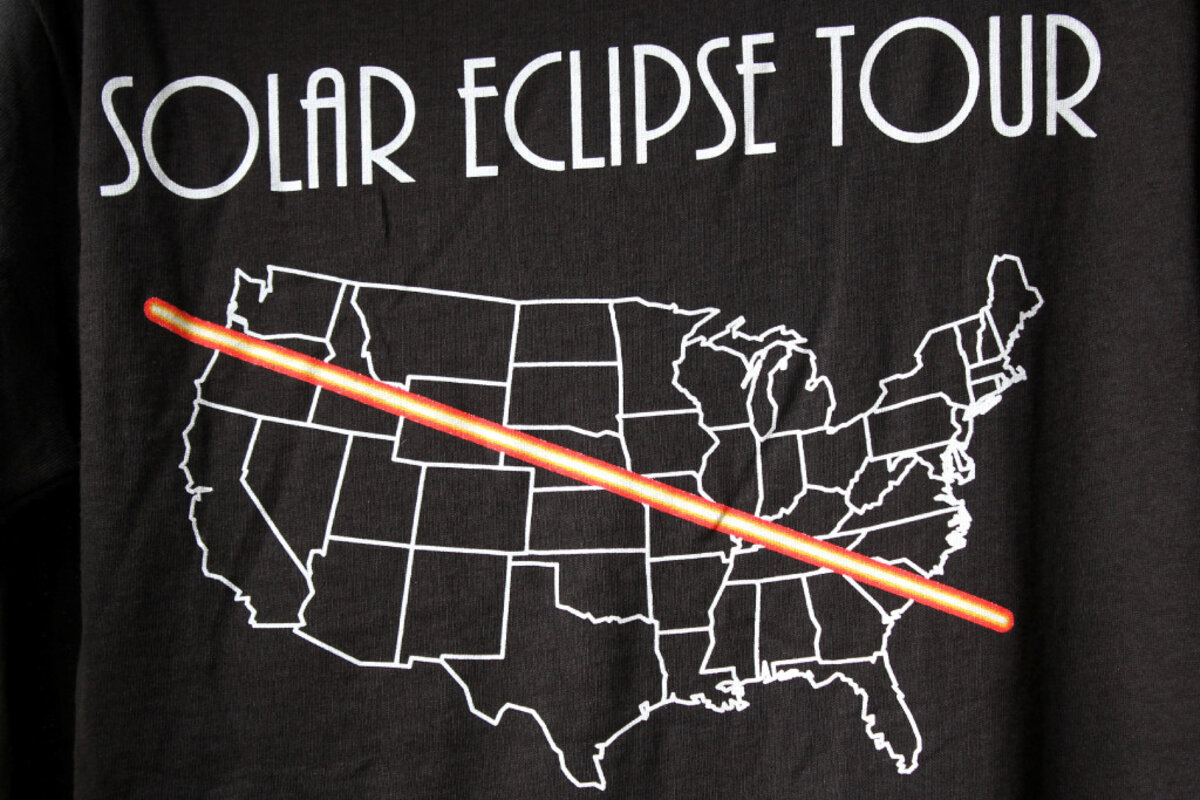

This story about the human senses misreading a celestial event as eternal darkness might be useful as many Americans prepare to experience a total solar eclipse on Aug. 21. The United States now seems as much under a shadow of hatefulness as it will be Monday under the darkness of the moon’s shadow from Oregon to South Carolina. The hate is being measured in rallies by white supremacists, in hate crimes against minorities, in public diatribes against elected leaders, in internet postings by hate groups, and even in arguments between friends and neighbors. And this dark mood may seem as permanent as the eclipse did for the Tboli people.

Astronomy has liberated much of humanity from false beliefs about the motions of the stars and planets. Earth is no longer seen as the center of the universe. The sun is just another star. The planets do not foretell human events. The light of scientific understanding over the centuries even informs us today that the darkness of a total solar eclipse will last only about 2 minutes, 40 seconds. No gongs need to be banged on Aug. 21.

Is there a similar lightness of understanding to lift America’s dark mood of hate? It cannot easily be found among national politicians or on cable TV. Only a minority of Americans look to the current president for moral leadership. Social media accelerates hate speech more than it spreads bonds of affections. Counterprotests against the protests of hate groups may make a moral statement; but they may not make peace.

Lifting this gloom will take individual acts of faith that the natural affection among diverse people can return to the American landscape. Such moments of courage, understanding, and love are not as easily measured as acts of hate. Yet they are more real and eternal.

A good example was recorded in a New Yorker magazine article about the clergy of Charlottesville, Va., coming together before the Aug. 12 protests. The coalition of local faith leaders, who call themselves the Charlottesville Clergy Collective, wanted to be prepared for the right-wing march and the clash over the city’s Confederate monuments. On the morning of the protests, the group’s leader, Alvin Edwards of the Mt. Zion First African Baptist Church, invited people to a worship service to help bring calm to the event. “We were trying to be prayerful, and I’m grateful for that, because I believe it would have been worse if people hadn’t prayed,” he told the magazine.

Such goodness of thought, whether expressed in prayer or in daily activities, has the power to dispel a belief that hate is an everlasting presence. It may not be as loud as a gong. But it works just as well in brightening hearts eclipsed by dark moods.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Keep your attention on the light

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

Sometimes life can feel like a cave-in: Suddenly the ceiling falls in on us and we’re left in darkness. But light pierces darkness, and the light of divine Love is the brightest, most powerful light there is. In a dark cave, it’s encouraging to realize that behind even the smallest pinprick of light is the full radiance of the sun. Similarly, behind even the smallest glimpse of divine inspiration is absolutely all of God and His infinite love. When we let divine Love permeate our thinking, we are changed for the better. The darkness may seem daunting, but the light that is God is infinitely more, and can lift us out of any darkness.

Keep your attention on the light

Suppose you were inside a cavern and there was a cave-in at the entrance. There would be such utter darkness, along with an immense amount of dust. Then, imagine, as this dust settles, that you perceive a tiny pinprick of light. No doubt you would focus hard on that tiny light beam and work tirelessly to get to it. Even though surrounding you is mainly darkness, that little ray of light would have all of your attention and might give you tremendous hope!

Sometimes, it might feel that life is like that cave: Suddenly the ceiling falls in on us, and we’re left in darkness. At these times, I’ve been encouraged by the idea that in every instance, God, divine Love, is there, comforting and caring for us. And best of all, God communicates His infinite love to each of us. The light of divine inspiration – healing inspiration – pierces darkness, provides hope, and guides us to freedom.

One experience I had years ago illustrated this in a very modest but meaningful way for me. When I was in high school, the opportunity to participate in an activity that gave me a deep sense of fulfillment was unexpectedly taken away from me. I’d never been one to feel depressed and hopeless, but I found myself feeling that way now.

For several weeks, I felt lost. But right at the beginning of the Bible, it says, “Let there be light” (Genesis 1:3). That is exactly what happened. I walked to a park near where I lived. Still feeling so sad and beaten, I prayed. I thought of another Bible verse: “All things work together for good to them that love God” (Romans 8:28).

To me, this felt exactly like a beam of light piercing a cave’s inky darkness. All that was required of me, I saw suddenly, was to love God. We are the very spiritual reflection of divine Love, created to love God and each other.

This got my full attention. Following that beam of inspiration, everywhere I went and in everything I did from that point forward – including schoolwork and chores at home – I tried to live the spirit of my love for God. Same with everything I said. I became much more conscious of God’s presence and care for every one of us, and the mental darkness lifted as my love for God grew more than ever.

Within three days, an opportunity to do the activity I loved in a setting rarely open to high school students emerged, and I was selected to participate. This turn of events was just amazing to me; it was an experience full of personal and spiritual growth that has served as a beacon of light for me in much more challenging times.

The founder of The Christian Science Monitor, Mary Baker Eddy, writes in the beginning of “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures”: “To those leaning on the sustaining infinite, to-day is big with blessings. The wakeful shepherd beholds the first faint morning beams, ere cometh the full radiance of a risen day” (p. vii).

In a dark cave, it’s encouraging to realize that behind even the smallest pinprick of light is the full radiance of the sun. Similarly, behind the smallest beam of inspiration is absolutely all of God and His love. Keeping our attention on that beam of inspiration and letting divine Love permeate our thoughts, we are changed for the better. The darkness may seem daunting, but the light that is God, good, is infinitely more so; and it can lift us out of any darkness.

A message of love

Coming to remember

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, we'll look at a key dilemma for opposition candidates in Venezuela: Do they participate in upcoming elections or sit them out in protest?