- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- For women candidates, a moment of possibility and urgency

- In Britain’s Parliament, a deepening swipe at culture of harassment

- On gun violence, blaming mental illness may only deepen stigma

- In pockets, Puerto Rico’s recovery begins to feel like a fresh start

- France lands a new cultural outpost in Abu Dhabi

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for November 10, 2017

Never mind Big Data. A little basic database management could go a long way toward guiding the decisionmaking that serves the common good.

The well-being of veterans hasn’t received much attention lately in the garish carousel of the news cycle. But here’s some promising news for this Veterans Day weekend. A pair of senators – one from each party – introduced legislation Thursday that would compel the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to keep track of problem medical providers that victimize vets and then skip out, crossing state lines and setting up shop again.

That came in response to a major investigation by USAToday that revealed “mistakes and misdeeds” by VA staff on that front.

A database needs more than building. It also needs vigorous use. That became clear after the US Air Force was found to have failed to report the Sutherland Springs, Texas, shooter to a list meant to keep those convicted on domestic violence charges from buying guns.

Other examples keep surfacing. One report this week revealed that a third of doctors in Massachusetts are not checking a state database on opioid abusers before they prescribe opioids for them, as required by law. The worthy aim of that database: to keep drugs out of the hands of people who go “doctor shopping” to gain access.

In areas from sea ice to sexual offenses, patterns of numbers tell stories worth hearing. Are we listening?

Now to our five stories for your Friday, intended to highlight new possibilities, deeper understanding, and cultural bridge-building.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

For women candidates, a moment of possibility and urgency

Virginia delivered a high-profile political surprise in its gubernatorial race. Separately, it turned up evidence of a great national stirring – one led by women candidates in races at all levels.

Jennifer Carroll Foy is one resilient woman. During her campaign for the Virginia House of Delegates, she learned she was pregnant with twins, went on bed rest, delivered the babies very early – and still won her race. What’s more, she was one of 11 women Democratic candidates who took over Republican-held seats, a display of female power that is no coincidence. Across the United States, in Tuesday’s off-year elections, women prevailed in many key races: in the Washington State Senate, where a special election flipped control of the chamber to the Democrats; in mayoral races in Seattle, Manchester, N.H., and Charlotte, N.C.; and in New Jersey, where the nation’s first black female Democratic lieutenant governor will soon be seated. Since President Trump’s election a year ago, women around the country have flooded political training programs, and many have declared candidacies. Tuesday’s elections provided two clear takeaways for women: Don’t be afraid to take on incumbents, despite seemingly long odds. And don’t wait to be recruited, just jump in. “These women really defied conventional wisdom – 30 percent of Democratic women who ran as challengers [in Virginia] won,” says Debbie Walsh of Rutgers University. “They were in many ways fearless in throwing themselves into these races.”

For women candidates, a moment of possibility and urgency

Jennifer Carroll Foy is one resilient woman.

Three weeks after announcing her candidacy for the Virginia state legislature, Ms. Carroll Foy discovered she was pregnant – with twins. That led to bed rest, and a very premature delivery. But she kept on running, and on Tuesday, she became one of 11 Democratic women to win Republican-held seats in the Virginia House of Delegates, bringing her party to the brink of a majority that few saw as even possible.

The Virginia house will go from 17 women out of 100 members to at least 28, with some races still undecided – a display of female power that was no coincidence. Across the country, in Tuesday’s off-year elections, women prevailed in many key races. In the Seattle suburbs, prosecutor Manka Dhingra won a special election for a Washington state senate seat – flipping control of the chamber to the Democrats. Seattle also elected a woman as mayor, as did Manchester, N.H., where Joyce Craig will become the first woman ever to hold that position. Charlotte, N.C., just elected its first black female mayor, and New Jersey will soon seat the nation’s first black female Democratic lieutenant governor.

Since President Trump’s election a year ago, women around the country have flooded political training programs, and many have declared candidacies. Tuesday’s elections provided two clear takeaways for women thinking of running for office: Don’t be afraid to take on incumbents, despite seemingly long odds (historically, incumbents win at least 90 percent of the time). And don’t wait to be recruited, just jump in.

“These women really defied conventional wisdom – 30 percent of Democratic women who ran as challengers [in Virginia] won,” says Debbie Walsh, director of the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J. “They were in many ways fearless in throwing themselves into these races.”

The success of female candidates in Virginia in particular – where Democrats also swept the statewide races, in an election seen in part as a referendum on Mr. Trump – is something that Democratic activists will be hoping to replicate across the country in the 2018 midterm elections.

Many of Virginia’s new female state delegates are also minorities, a reflection of an increasingly diverse state. Carroll Foy is black, two others are Latina, one is Vietnamese, one is Filipina, and one is transgender. And many of them say their decision to run came from a visceral reaction a year ago to the election of Trump as president.

“I decided to run on my own,” says Carroll Foy, who works as a public defender, in an interview. “I remember watching the election last year, and knowing how disappointed and frustrated and angry and hopeless I felt. I knew that there had to be a response to Trump.”

Younger women with younger children

Another newly elected Virginia delegate, Kelly Fowler, speaks of taking her eight-year-old daughter – born on the day Barack Obama was inaugurated in 2009 – to the Women’s March last January. That’s when she decided to run.

New delegate Kathy Tran, a refugee from Vietnam as a little girl, gave birth to her fourth child shortly after Trump’s inauguration, and decided to run soon thereafter. She campaigned door-to-door with baby Elise – named for Ellis Island – at her side.

All these stories point to another trend: Women with small children are no longer shying away from running for office.

“We are seeing younger women with younger children,” says Ms. Walsh. “Everything we know about women in politics may be going out the window.”

Still, she and others caution against over-interpreting Virginia’s election results, noting that it has become an increasingly Democratic state, particularly among women, who voted for Gov.-elect Ralph Northam (D) by 22 points. Hillary Clinton’s margin among women there last year was 17 points.

Tuesday’s election “feels a little like the legislature is catching up with the electorate,” says Walsh.

Republicans in Virginia, too, have worked hard to recruit and elect women candidates. The party’s nominee for lieutenant governor was a woman, state Sen. Jill Vogel. And all the Democrats’ statewide office-holders are men, both today and when the new governor is installed. But the numbers don’t lie. In Tuesday’s election, 27 of the female challengers for Virginia’s House of Delegates were Democrats, and only three were Republicans.

Issues like health care – the top concern of Virginia voters overall, according to exit polls – and reproductive rights were key for both Democratic women candidates and voters alike.

Tom Davis, a former Republican congressman from northern Virginia, knows his party has a woman problem but, he adds, referring to voting trends, “the Democrats have a man problem.”

Above all, Democratic leaders are focused on recruiting candidates they think can win – and in the era of Trump, with voters in both parties crying for outsiders, that often means women.

“We had made a concerted effort as a caucus to recruit more women candidates,” says Charniele Herring, chair of the Democratic Caucus in the Virginia House of Delegates. “Some we had tried to recruit for years to step up.”

Hala Ayala, a cybersecurity expert and single mom in an outer suburb of Washington, is one whom Virginia Democrats had long tried to recruit. In January, she was an organizer of the Virginia contingent to the big women’s march the day after Trump’s inauguration. Now, she’s preparing to take her seat in the House of Delegates.

But Ms. Herring is also a big believer in women who self-activate. “I always tell women, ‘Don’t wait for someone to ask you to run, because then you probably never will,’ ” she says.

A long-shot bid

Carroll Foy is one of those women who didn’t wait. And her run for a seat in a racially mixed outer suburban area that was being vacated by a Republican may be the most memorable of this cycle. It began as a long-shot bid in the Democratic primary, against a party-establishment favorite who had already been running for more than a year. He outraised Carroll Foy by four to one, and had racked up a pile of local endorsements.

When Carroll Foy discovered she was pregnant, she plowed ahead, and tried to keep it private as long as possible, so as not to distract from her campaign and her message. When she told one person, early on, she says, the response was: “‘How are you going to run for office and work and be a mom? It’s going to be impossible.”

But she knew she could do it, with the support of her husband, family, and campaign team.

“I knew that I didn’t have to choose between being a mother, or an attorney, or a wife, or a candidate,” she says. “Those should all be ‘ands.’ ”

When she went on bed rest, just two days before the June 13 primary, her husband and campaign manager swung into action. She won the primary by 14 votes after a recount. On July 5, her twin sons were born, almost 18 weeks early. This week, she won the general election by a wide margin.

What in her background had prepared her for this challenge?

She credits her faith, and her education at Virginia Military Institute, where she was one of the first women of color to attend. There she learned time management and organizational skills, and “how to work with people who have a great disdain for you, and don’t want you in the room.”

She had also been a foster parent, an experience that gave her “an understanding of how to meet the needs of people in my community, not just identifying problems, but how to be part of the solution,” she says.

“I was raised by my grandparents,” she adds. “What if they hadn't taken the time out? What if they hadn't given me the opportunity, where would I be?”

Now she’s a mom herself, and the next phase of her journey of “ands” – wife, mother, lawyer, and soon a state delegate – is about to begin. She plans to keep working 50-hour weeks as a public defender, and take leaves of absence when the legislature is in session.

She says her “huge family support system,” including her mother-in-law, will keep helping her and her husband juggle everything. And the babies? Both now weigh more than 7 pounds. Xander has just come home from the hospital, and Alex should be home early next week.

“They’re doing wonderfully,” she says.

Share this article

Link copied.

In Britain’s Parliament, a deepening swipe at culture of harassment

Yesterday, the US Senate mandated sexual harassment training for its members and their staff. In Westminster – with more than 200 women members of Parliament, including the prime minister herself – a harassment scandal has prompted a more active introspection. “This can only be a watershed moment for women in politics,” says one Labour activist, “if our discourse moves from focusing on individual men to the wider, systemic problems....”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Nicola Slawson Contributor

As the reverberations of the Harvey Weinstein scandal ricochet around the world, the hallowed halls of Westminster are not immune to shocks. More than a dozen British members of Parliament have been accused in recent days of sexual harassment; one cabinet minister has been brought down, and the scandal continues to rumble on. Female MPs from both the Conservative and Labour parties are seizing on this moment as an opportunity to strengthen parliamentary rules about harassment reporting, and the government has promised new procedures. But it’s not just a matter of procedures, and rooting out established patterns of thought and behavior in the “old boys’ club” that Parliament often resembles is a challenge of a different order. One female peer says that “a complete cultural change” is called for; she suggests that won’t happen until women fill at least half the seats in Parliament. And it is not clear that much will change unless the British public gets really angry about sexual harassment. That does not seem to have happened yet.

In Britain’s Parliament, a deepening swipe at culture of harassment

It started with a Whatsapp group.

The Weinstein scandal had just started to unfurl in the news, and across the British political scene, women began sharing their own stories of sexual harassment on the instant messaging app.

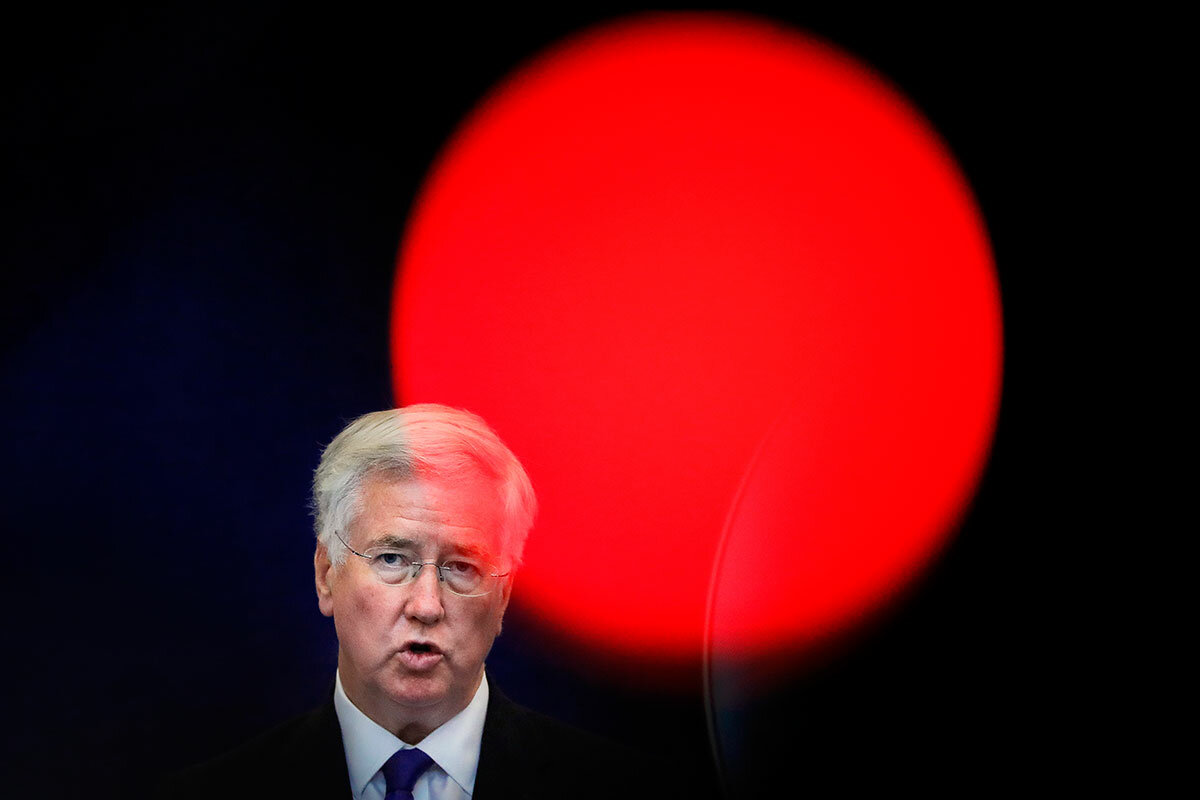

The term “handsy” became the word of choice to describe male members of Parliament with wandering hands, and before long names and alleged offenses – including serious cases of rape and sexual assault – had spread like wildfire around the Palace of Westminster. They soon spilled out in the press and quickly claimed a top-level victim: Prime Minister Theresa May’s right-hand man, Defense Minister Michael Fallon.

Now, with eight MPs from the ruling Conservative party and four more from the opposition Labour party facing sexual misconduct allegations, along with MPs and party officials from most of the other political parties, there is a palpable feeling in Westminster that women from all parties have had enough, says Sam Smethers, chief executive of the Fawcett Society, which campaigns for women’s rights. And they are looking for concrete ways to remake British politics' boys club into something more inclusive.

“Women from all sides of the house are clearly coming together to address it,” she adds. “This is a positive move and will drive change.”

'Radical action' needed

After a series of allegations against Mr. Fallon, including one that he had lunged at a junior newspaper reporter, trying to kiss her on the lips, forced him to resign, Ms. May moved quickly to try to defuse the scandal, holding cross-party talks earlier this week and establishing a new obligatory grievance procedure involving a mediation service.

Many female MPs, though, called the plans disappointing, saying they did not go far enough. And many are now arguing that much more radical action needs to be taken.

Labour party activist Bex Bailey is calling for an independent and impartial body to be set up to deal with allegations. Ms. Bailey waived her right to anonymity recently and told the BBC that she had been raped by someone senior to her in the party six years ago and that she had been warned not to take the matter further if she wanted a career in politics.

Bailey spent three years on the Labour party’s national executive committee trying to make reporting of sexual harassment easier. She pushed through a new, more sensitive complaints procedure for the party, but it is not enough, says Sabrina Huck, a Young Labour activist.

“Young members don’t feel safe reporting senior Labour members in a position of power” because of “fears what it means for their personal prospects,” she says. “Labour is like a family – everyone knows everyone. It does not seem fair to have to expose yourself to people who you are likely to have dealings with again in the future.”

Ms. Huck, like many women, also wants to broaden the conversation about sexual harassment. “This can only be a watershed moment for women in politics if our discourse moves from focusing on individual men to the wider, systemic problems at the root of this scandal,” she argues.

A need for more women?

She is not the only one to call for a sea change at Westminster. Shami Chakrabati, a senior Labour member of the House of Lords, says that while improved procedures are welcome, a “complete cultural change” is needed.

“In Westminster, there is a particular problem, which is that politics is tribal and so you don’t necessarily get the solidarity or honest process that you would get in a normal workplace,” she suggests.

“You get this message that you’d be letting the side down if you complain," she adds. "I think the culture would get better if there were more women. We need to get 50 percent. It’s not good enough until it is, and more women need to be in senior roles.”

Women currently make up 32 percent of MPs – 45 percent within the Labour party but only 21 percent of Conservative MPs. Only a quarter of the journalists accredited to cover Parliament are women.

One way to tackle the hyper-masculine culture might be to implement recommendations in the 2016 Good Parliament report. Among other things, the report proposed making it legally obligatory for political parties to present women candidates in at least half the electoral constituencies they contest.

It also suggested assigning 40 percent of journalistic accreditations to women, and allowing female MPs to breast feed in the debating chamber.

The report, by Sarah Childs, a professor specializing in politics and gender at Bristol University, was commissioned and endorsed by the Speaker of the House of Commons John Bercow.

Outcry, yes. But outrage?

Rainbow Murray, an expert on women in politics at Queen Mary University in London, says the Good Parliament report’s recommendations are more important than ever in light of recent revelations.

“It is an excellent blueprint for where to go next, but the problem is there are a lot of people who have a vested interested in maintaining the status quo,” she says. “Change to empower those that have previously been marginalized never sits well with those who have the power.”

Professor Murray fears that necessary changes will not happen unless the British public expresses significant outrage at the current levels of sexual harassment. “It’s not clear yet whether that’s the case,” she says.

“There’s certainly been a lot of outcry, but it’s also true that there’s a level of ingrained sexism throughout society, with some saying that this is a fuss about nothing,” she adds.

One veteran Conservative MP, Sir Roger Gale, has suggested the scandal is becoming a “witch hunt.” Kathy Gyngell, co-editor of the Conservative Woman website, told a radio interviewer that the scandal demonstrated “a total surrender by Theresa May to the left and the feminists.”

“Not everyone is ready to accept change,” Murray sighs.

On gun violence, blaming mental illness may only deepen stigma

The search for blame after the deadly Texas shooting last weekend led some to point to lax gun regulations and others to issues around mental health. The latter may seem an easier handle. This story explores why it’s not that simple.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

Jessica Mendoza Staff writer

It’s a common misperception: Mass killers are mentally ill. In fact, fewer than 1 in 6 has been diagnosed as psychotic, according to a 2015 paper. Past violent behavior, a history of animal cruelty, childhood maltreatment, access to guns, or being young and male are more reliable indicators. So when President Trump portrayed last Sunday’s church shooting in Sutherland Springs, Texas, as a mental health problem – the killer had escaped from a mental health facility in 2012 – he was really pointing to an exception rather than the rule. Previous shootings have prompted similar comments from House Speaker Paul Ryan and former President Barack Obama. The problem with that is that it misrepresents the problem and stigmatizes mental health at a time when people struggling with mental illness are already hesitant to come forward and ask for help, experts say. According to one group, nearly 60 percent of adults with a mental illness don’t receive any mental health services in a given year. James Alan Fox, a Northeastern University criminologist, says the linking of mass shootings with mental health also “perpetuates a stereotype of the mentally ill as dangerous.”

On gun violence, blaming mental illness may only deepen stigma

The day after Devin Kelley perpetrated America’s worst mass shooting in a place of worship – killing 26 and wounding another 20 at the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, Texas – President Trump called it a “mental health problem at the highest level.”

Some mass shooters have been diagnosed with mental illness. Jared Loughner, who killed six and severely wounded then US Rep. Gabrielle Giffords in 2011, was found by psychiatrists to have a mental disorder. Ditto for James Holmes, who killed 12 people at the Century movie theater in Aurora, Colo., in 2012.

Mr. Kelley himself escaped from a mental health facility in New Mexico in 2012, after being accused of assaulting his wife and severely beating his baby stepson while serving with the US Air Force.

But few mass killers have a clinically diagnosed mental illness. Thus, pointing to mental illness as the cause of gun violence is not only misleading, say mental health and gun violence experts, it could also increase the stigma around it and make people less willing to seek help.

“Imagine if [Mr. Trump] had said, ‘veteran’ – that this was a ‘veterans’ issue,” says Jeffrey Swanson, a professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, N.C. “He’d besmirch the whole community. Well, that’s what he’s doing with mental illness.”

The best indicator of future violent behavior is past violent behavior, experts say. A history of animal cruelty, childhood maltreatment, access to guns, and being young and male are also more reliable indicators of future violence than a diagnosed mental health disorder, they say.

Perpetuating stereotype

Only 3 percent to 5 percent of violent acts can be attributed to a person living with a severe mental illness, according to the Department of Health and Human Services, while people linked to those illnesses are actually 10 times more likely to be victims of violent crime than the general population. Of 88 mass shooters – those who had killed four or more people in the US – since 1966, only 14.8 percent were diagnosed as psychotic, according to 2015 paper by Northeastern University criminologist James Alan Fox, a gun violence expert who maintains a database of indiscriminate mass shootings.

Trump is not the only one to suggest that improving mental health services could prevent mass shootings. Last year, President Obama said as much in a speech that recalled the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut. Days after last month’s mass shooting in Las Vegas – the deadliest in US history – House Speaker Paul Ryan did the same.

It “perpetuates a stereotype of the mentally ill as dangerous,” says Dr. Fox, author of several books on mass shootings, including “Extreme Killing: Understanding Serial and Mass Murder.”

That stigmatization may make it even more difficult for professionals to find the people who do need help.

“Suggesting that this is what people who have mental illnesses do likely means that if I’m someone with mental illness, I’m less likely to reach out and seek help,” says Arthur Evans Jr., chief executive officer of the American Psychological Association.

Staffing shortage

The ability to help is further hampered by a serious lack of resources and manpower, often leading to long wait lists for treatment. Two-thirds of Texas counties have no working psychiatrist, according to the Texas chapter of the National Association of Mental Illness (NAMI), a situation similar to other parts of the US.

And with more than half of mental-health providers aged 55 and older and nearing retirement, there are few people to take their place. Only 4 percent of US medical school graduates have been applying for residency training in psychiatry, according to a 2015 study.

These factors help explain why, according to NAMI, nearly 60 percent of adults with a mental illness don’t receive any mental-health services in a given year. That increases the risk that someone diagnosed with mentally illness may commit a violent act.

“If [someone] has a psychotic episode, they don’t have time to wait and get help, and that’s when violence happens,” says Sarah Feuerbacher, director of the Center for Family Counseling at Southern Methodist University in Plano, Texas.

There are some examples of state-level reforms. In November 2013, a mental-health facility in Virginia discharged Austin “Gus” Deeds because no psychiatric bed was available and he couldn’t be held in emergency custody for more than six hours. Less than 24 hours later, he attacked his father with a knife and committed suicide.

Six months later, the father – state Sen. Creigh Deeds – got a law passed reforming several elements of Virginia’s emergency mental-health system.

Back in Sutherland Springs, scene of the latest mass shooting, Eileen Anderson, who helps run the local historical museum, has been looking at her own family’s situation in a new light. Decades ago, her daughter was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and still sees a psychiatrist, takes medication, and, most important to her mother, continues to communicate with her.

“The love has kept us together, that’s the main thing,” she says. “With the things that happened to this guy [Kelley, the shooter], I mean it’s just carried over and over and over, until it just…”

Her voice trails off. “They need to love their family,” she says, after a while.

In pockets, Puerto Rico’s recovery begins to feel like a fresh start

The effort to rise back up after a hurricane’s punch has been frustratingly slow. Many have left the island. But some on the island are now shifting their focus to a future defined by resilience – and finding that to be exhilarating.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

In Puerto Rico, the rallying cry “reconstruir mejor” – build back better – captures the mounting conviction that hurricane Maria, which roared across Puerto Rico as a Category 4 storm, was not a fluke. For many here, it was likely the harbinger of a new reality in the Caribbean, and as a result, a lot needs to change. That means no traditional wood-and-corrugated-metal home construction and no centralized power generation system dependent on imported fuels. But an appealing slogan won’t help without new thinking and a unity of purpose and political cooperation. And recovery is further challenged by a preexisting economic crisis. Many hope the frustrations of the slow-motion recovery will be outweighed by the sense of opportunity. “[S]o many of us feel we in Puerto Rico now have an unexpected opportunity to do things in a new way,” says the head of a nonprofit that focuses on sustainable development and helps young entrepreneurs network with Puerto Rico’s influential diaspora. “I think we have a chance to work together as a country to try something new and better.”

In pockets, Puerto Rico’s recovery begins to feel like a fresh start

As Puerto Rico continues the slow process of recovery from September’s near-knockout one-two punch of hurricanes Irma and Maria, the phrase “build back better” has become something of a mantra.

From the governor’s office to still-dark industrial parks, from roofless homes to flattened community health centers, the imperative to “reconstruir mejor” has sprouted as quickly as the fresh green shoots bursting from the swaths of bowed trees that now define the tropical island’s landscape.

Speaking Thursday to a convention of Puerto Rican builders, Governor Ricardo Rosselló said that in the wake of the destruction of Maria, the island was at a crossroads where it could choose to build a more resilient future, with safer roads, better-placed schools and housing, and a stronger health system.

"This is a grand opportunity for Puerto Rico to rebuild in a planned and correct manner," he said.

The rallying cry captures the mounting conviction that Maria, which roared across Puerto Rico as a Category 4 storm, was not a fluke. For many here, it was likely the harbinger of a new reality in the Caribbean, and as a result, much must change.

That means no traditional wood-and-corrugated-metal home construction, no decades-old shore-front development model, no centralized power generation system dependent on imported fuels.

But “building back better” won’t happen by repeating an appealing slogan. It requires new thinking and a unity of purpose and political cooperation (both in Puerto Rico and between the US territory and the federal government). And recovery is further challenged by a preexisting economic crisis.

Many hope the frustrations of the slow-motion recovery will be outweighed by the exhilarating sense of opportunity. It’s the idea that Puerto Rico can serve as the laboratory for a new model of resilience in the era of climate change.

“We still have so many immediate needs to tend to ... but at the same time, so many of us feel we in Puerto Rico now have an unexpected opportunity to do things in a new way,” says Isabel Rullán, founder and director of ConPRmetidos, a nonprofit that focuses on sustainable community development and connecting young entrepreneurs with Puerto Rico’s influential diaspora.

“Many are things we have talked about and even started working toward [before the storms], like a sustainable building and development model,” she says. “But now they seem more urgent. I think we have a chance to work together as a country to try something new and better.”

Constructing a better Puerto Rico will take more thinkers like Ms. Rullán, many experts say.

Operating from the Foundation for Puerto Rico, a beehive of activity in the Santurce neighborhood of San Juan, Rullán is focused on getting micro solar units and batteries to communities still without power more than five weeks after the storms. Around her, other 20-somethings from a collection of nonprofits organize food distribution, medical caravans, and roof-tarp deliveries.

Across Puerto Rico, volunteers from the island and elsewhere have joined the thousands of military and civil defense personnel addressing still-staggering needs. Teams of engineers put temporary covers on roofless houses, doctors fan out to remote communities, and groups like Rullán’s provide the means of supplying darkened communities with temporary lighting.

Rullán says she’s determined not to let immediate recovery efforts obscure the longer-term potential of the moment.

But many Puerto Ricans are worried that the impulse to think in bold new ways about the future will be crushed under the weight of the island’s slow recovery and chronic economic and political challenges.

“After Maria, nobody in Puerto Rico thinks we should just build things back the way they were, that we should proceed like nothing has changed, because everyone knows things can’t be the same,” says Jorge Fernández-Porto, executive director of the Puerto Rican Senate’s Commission for Development of Community Initiatives.

“But when you get up every day and it seems nothing has changed – the power lines are still in the street, businesses are not opening, too many people still don’t have electricity and clean water – it’s depressing,” he says. “It risks drowning this hope of turning a disaster into an opportunity.”

Indeed, not everyone is able to envision these disasters as an opportunity. Many Puerto Ricans – United States citizens with the ability to move at will to the mainland – are heading for the exits. Some estimate that as many as 1,000 people are leaving daily. With this accelerated rate of departure, by 2020 the island’s population could fall below 3 million for the first time in 70 years.

Puerto Rico’s exodus is not new: Some 500,000 have moved to the mainland over the past two decades. But the profile of those departing now is particularly worrisome: Young families concerned about schools and jobs make up a large part of the mix. So do university students and budding professionals who may be the needed engines of change and new thinking.

“There’s no question we’ll suffer a significant loss of productivity, of both the practical and intellectual types,” Mr. Fernández-Porto says.

Some establishments open, many not

In central San Juan many restaurants are open, and some shopping malls are humming again – good spots for those still without power to charge cellphones. But elsewhere, many businesses are quiet and industrial parks appear to be on long-term holiday. Some iconic tourist resorts have locked their gates, and hotel groups like Marriott have announced that some of their Puerto Rico hotels will remain closed for as long as two years.

While the damage and lost productivity from hurricanes Harvey and Irma are valued at $150 billion in Texas and Florida, Maria alone is estimated to have caused $100 billion in similar losses in Puerto Rico. No more than a quarter of the island’s economic activity is thought to be up and running.

That picture would be dire enough, but Maria’s blow comes on top of a debilitating debt crisis and a dozen years of recession. The economy shrank by a quarter in that period, in part a result of Washington rescinding decades-old business tax incentives. Often referred to as the Western Hemisphere’s Greece, Puerto Rico has been in federal bankruptcy court since May in an effort to stave off creditors and restructure the island’s $73 billion debt.

Experts fear that wrangling over the debt and how to keep the island afloat could smother the nascent conversation about how to go forward.

“I see two big roadblocks that risk sidelining the ‘build back better’ effort before it really takes off, and both have to do with government – both on the island and between the island and the federal government,” says Dante Disparte, chairman of the American Security Project’s Business Council for American Security and an active member of Washington’s Puerto Rican community.

“One is the lack of trust among leaders and a lack of transparency in governing institutions,” he says. But there’s also the debt burden: “How can you have a productive discussion on building a better future when you don’t know how you’re going to pay wages and keep essential services going?”

Congress last month sent President Trump a $36 billion disaster bill that includes a $5 billion lifeline for Puerto Rico. But experts say that is only the tip of what will be necessary.

“We should all be able to agree on the idea of building back better, but problems arise as soon as you take the next step and ask, ‘What does that mean?’ ” says Edwin Meléndez, director of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at New York’s Hunter College.

He points to the need to rebuild more than 100,000 damaged or destroyed homes. “Just saying the obvious, that houses must be built better, isn’t enough,” he says. “You need policies and new standards to guide and enforce that,” which can “run up against entrenched interests.”

Still, Mr. Disparte is among those who remain optimistic that Puerto Rico’s recovery can be something of a global model.

“We have a chance to build the textbook case of what resilience and sustainability can look like, particularly in terms of climate change, and that’s exciting,” he says.

Laboratory for big thinkers

Already, Puerto Rico post-Maria is serving as a laboratory for big thinkers.

Last month, Elon Musk met with Governor Rosselló to discuss how Tesla’s technology for solar panels and energy storage batteries could help revolutionize energy delivery here. By late October, the technology was powering San Juan’s Children’s Hospital – a project that Mr. Musk declared just the first of many.

Also in October, Google parent company Alphabet announced it would launch “internet balloons” into the stratosphere above Puerto Rico to replace downed cell towers. Several balloons are now aloft, providing internet access in remote areas of the island.

Disparte says he believes that spirit of innovation and desire to demonstrate solutions to global challenges could even prompt Amazon to choose Puerto Rico for its much-ballyhooed second headquarters project. Puerto Rico’s economic development authority joined 238 North American cities in submitting a proposal.

“If you consider how these big innovators think, the idea of an Amazon choosing Puerto Rico makes sense, both from a practical business perspective – the island has a capable bilingual workforce – and from the loftier image perspective,” Disparte says. “The island’s rebuilding project offers Amazon the opportunity not just to be an anchor tenant in this model” for sustainable development in the era of climate change, “but to change the arc of history.”

That said, Amazon choosing an island with debilitated infrastructure and housing stock for its new headquarters seems like a long shot.

It’s no coincidence that the Tesla and Google projects were among the first new initiatives. Energy and telecommunications have emerged as two of the biggest challenges for the “build better” vision.

The island’s antiquated and bankrupt electrical generation and distribution enterprise, the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority, was a major impediment to progress before the storms. It’s a centralized system that relies largely on imported fuels, with plants far from population centers.

Replacing the system with one that incorporates a significant role for renewable energy sources and community-empowering microgrid innovations will almost certainly emerge as a key test of the island’s ability to advance its vision of a better-built future.

“Most of the infrastructure will be replaced, so this is the moment to begin an electric energy revolution,” says Efraín O’Neill-Carrillo, director of the Power Quality & Energy Studies Laboratory at the University of Puerto Rico-Mayaguez. “A more [decentralized and community-based] approach should guide the reconstruction, which could not only result in a faster recovery in some areas, but would also support the much-needed transformation of Puerto Rico’s electric infrastructure.”

Still, delivering an “energy revolution” will require the kind of new thinking that is nourishing the “build back better” vision.

Creating effective energy policies is more difficult than the island’s economic challenges, says Dr. O’Neill-Carrillo. “Renewable-based microgrids entail going from passive users to engaged energy actors. This new energy vision requires ... new responsibilities for the government, the workforce, and the citizenry.”

No one thinks the “build back better” vision is assured. But the possibility of improvement has pushed many here to action.

Back at the Foundation for Puerto Rico, where Rullán is organizing the next round of solar battery distributions, New Yorker David Ramirez finds himself back in the neighborhoods of his childhood. Mr. Ramirez left when he was 18, but today is distributing water, helping with house repairs, and trying to “keep people’s hope alive,” he says. He wants to make sure this opportunity to reimagine Puerto Rico isn’t lost.

“This is a turning point on the island. You really get the feeling that out of this disaster could come something different and better if people here seize the opportunity,” says Ramirez, who is developing an online furniture rental business in New York.

“This terrible disruptive storm could end up being seen as Santa Maria, the savior of the island,” Ramirez says. “Or, it could all turn out negative. “A lot of us want to help, but it’s going to depend on the people here and whether or not they figure out how to use this opportunity.”

– Staff writer Joseph Dussault contributed reporting from New York.

France lands a new cultural outpost in Abu Dhabi

There's no trace of the Louvre’s 18th-century facade or its glass pyramid. The prize-winning architect went for a filtered-light, Arab souk feel. But the famed French name and loaned art make this a modernist bridge.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

The Louvre Abu Dhabi opens to the public on Saturday, bringing the most recognized museum name in the world to the United Arab Emirates. And by lending its most valuable brand to the project, the French are also wielding power that’s been waning on the world stage but remains impregnable when it comes to cultural patrimony. To be sure, the deal kicked up a storm of criticism in France. There were those who objected to the Louvre and other institutions arguably selling their souls for petrodollars. But of all of the Western investments in the UAE, from museums to universities, the Louvre's vision is the most spectacular, says Martin Kemp, a professor emeritus of art history at the University of Oxford. “It’s a particularly French vision,” he says. “France as an operator on a world scale, obviously it is less [of one] financially and politically than it used to be, but in a way it can still [be one] culturally.”

France lands a new cultural outpost in Abu Dhabi

The latticed dome, nearly 600 feet in diameter and comprised of 8,000 metal stars that weigh together the same as the Eiffel Tower, plays with Gulf sunlight to form a “rain of light” – the signature of what is being touted as the most ambitious museum project of the 21st century.

The Louvre Abu Dhabi, perched on Saadiyat Island overlooking the sea, opens to the public on Saturday, bringing the most recognized museum name in the world to the United Arab Emirates. And by lending its most valuable brand, not to mention its know-how, to the project, the French are also wielding power that’s been on the wane on the world stage but remains impregnable when it comes to cultural patrimony.

Of all of the Western investments in the UAE, from museums to universities, the Louvre's vision is the most spectacular, says Martin Kemp, a professor emeritus of art history at the University of Oxford. “It’s a particularly French vision,” he says on the phone from Abu Dhabi. “France as an operator on a world scale, obviously it is less financially and politically than it used to be, but in a way it can still do that culturally.”

Ten years in the making, the Louvre Abu Dhabi is no replica of the 18th-century institution born during the French Revolution. The play of light and shadow under the dome gives the visitor the feel of being in a souk, of being in a grove of palm trees found in the oases of the UAE, says Jean Nouvel, the famed French architect who designed the building.

It is the first “universal museum” in the Arab world and bears testament to the capital's “golden age,” says Mr. Nouvel. It’s been billed as a bridge between East and West, reiterated by French President Emmanuel Macron, who attended the museum’s inauguration Wednesday evening.

The more than $1.2 billion deal was signed back in 2007 under then-President Jacques Chirac. It designated $525 million for the use of the “Louvre” title over the next 30 years and $750 million for French experts to oversee 300 loaned works of art from 13 leading museums. Visitors Saturday will be able to view Leonardo da Vinci’s La Belle Ferronnière, on loan from the Louvre, or Vincent van Gogh’s self-portrait, formerly housed at the Musee D’Orsay and Musée de l'Orangerie.

Tristram Hunt, director of Britain's Victoria and Albert Museum, commended France’s assertion of soft power, contrasting it with the introversion of Britain in the post-Brexit era. “While Napoleon’s invasion was hard power,” he wrote in the Guardian, referring to the military leader’s invasion of Egypt in 1798 to spread Enlightenment ideals, “Macron’s visit is all about the long-term insinuation of soft power. Yet it signals a hard truth: if Brexit Britain is going to find its feet as a global player, we need to be thinking about similarly ambitious displays of cultural bravado.”

The deal kicked up a storm of criticism in France. There were those who objected to the Louvre and other institutions arguably selling their souls for petrodollars. “The idea of selling or renting the Louvre brand abroad posed one problem,” says Laurent Martin, a professor of the history of cultural policy in France and Europe at the Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3. “To do so with a country that does not respect the values of liberal democratic societies of Europe posed another.”

One of the more concrete controversies to arise during the 10-year project was the abuse of migrant workers constructing the site, called out by Human Rights Watch – not exactly the stuff of les droits de l'homme (human rights), declared in France in 1789, four years before the Louvre opened to the public.

But none of this was on the agenda as the museum was inaugurated in the presence of kings and other rulers. Mr. Macron called it a showcase, as a “bridge between civilizations,” of “beauty of the whole world.”

Nouvel, a Pritzker Prize winner who met with the Anglo-American Press Association in Paris in September, told the group he sees the museum as a “testimony of this golden age, as was done in every city of the world in the past.” It was built not for decades but for centuries to come: “It is like a cathedral in this epoch, it’s exactly the same thing.”

“An architect who is ambitious is not ambitious for himself but because the project is so important,” he said. “The ambition is the real will to leave the best testimony of the epoch.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Thanksgiving’s ties to safety and comfort

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

Does the kind of giving expressed during the Thanksgiving season have any connection to curbing violence in the United States? Yes, according to a study by New York University sociologist Patrick Sharkey. He and his team found one reason for a big drop in violent crime in the US over the past quarter century was the role played by local nonprofit organizations and their generous donors. Private philanthropy, Dr. Sharkey says, took on the work of fortifying urban neighborhoods from within by building trust and social cohesion. Donations helped nonprofits build affordable housing and community gardens, turned empty lots into parks, and offered guidance to jobless youth. Many other factors, such as better policing and demographic changes, contributed to the drop in violence and a revival of cities. But this point about individual giving to nonprofits should now be clear: It can bring safety and comfort to communities.

Thanksgiving’s ties to safety and comfort

When President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation that set the last Thursday in November as a national “day of Thanksgiving,” he did so at the height of the Civil War. He asked Americans to entrust to God’s “tender care” all those who had suffered from the war’s violence. In the decades since, that spirit of care and giving has endured in the holiday season. Witness the many who will volunteer in soup kitchens this Nov. 23.

But does the kind of giving expressed during the Thanksgiving season still have any connection to curbing violence in the United States?

Yes, according to a new research study led by New York University sociologist Patrick Sharkey. He and his team found one reason for an astonishing drop in violent crime in the US over the past quarter century. It was the role played by local nonprofit organizations – and their generous donors.

Private philanthropy, Dr. Sharkey says, took on the work of fortifying urban neighborhoods from within by building trust and social cohesion. Donations helped such nonprofits as the Harlem Children’s Zone in Manhattan, Youth Guidance in Chicago, and the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative in Boston. They built affordable housing and community gardens, turned empty lots into parks, or offered guidance to jobless youth.

The study looked at data from 264 American cities spanning more than 20 years. It concluded that with every 10 additional nonprofits focusing on crime and community life in a city with 100,000 residents, the murder rate went down 9 percent. Overall, violent crime fell 6 percent because of their work.

Many other factors, such as better policing and demographic changes, contributed to the drop in violence and a revival of cities. But few scholars have noted the role of nonprofits, including those focused on the arts, humanities, or environmental protection in cities. A related study in 2012 by the National Conference on Citizenship found that states with a higher density of nonprofits had lower unemployment rates and better economic resiliency.

The US saw a rapid rise in the number of nonprofits from 1990 to 2013. Those that focused on neighborhood development grew from 5.50 per 100,000 residents to 22.51 per 100,000 residents. Those providing recreational and social activities for youth grew from 4.72 per 100,000 residents to 18.72 per 100,000 residents. Of major cities, Boston added the most nonprofits per population, perhaps accounting for its admired success in cutting gang-related killings in the 1990s.

The point about individual giving to nonprofits should now be clear. It can bring safety and comfort to a community in the throes of upheaval. That was the spirit of Lincoln’s Thanksgiving proclamation in 1863. And it can again be the spirit of Thanksgiving 2017.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Veterans and God’s healing love

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Ingrid Peschke

In wartime, many on the front lines, as well as those supporting them back home, have found that prayer becomes a lifeline. And many veterans who have suffered combat-related pain, illness, or loss continue to seek out a deep, healing love long after they have finished their military service. Turning to God, good, can provide inspiration that can bring needed comfort and protection to those facing fear or danger. As our divine Parent, God is always caring for everyone: “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil; for You are with me; Your rod and Your staff, they comfort me” (Psalms 23:4, New King James Version). God’s tender, healing, infinite love can reach veterans, and others in need, unimpeded by time and space.

Veterans and God’s healing love

Various countries around the world have their own unique ways to honor their veterans – men and women who have expressed courage, strength, selflessness, and great love in service to their country. For instance, the United States, Britain, Canada, and Australia each set aside a time in November to celebrate their veterans.

One time, on a flight home to Boston, I struck up a conversation with a former US Marine Corps commander who served in the Vietnam War. He affectionately referred to his combat unit as “his boys” and said he was fierce about keeping them safe. For several years during his service he lived on just two hours of sleep every night, only shutting his eyes at the break of dawn.

That commander’s description of care for his troops reminded me of the deep connection between a parent and child, and I came away from that conversation with a renewed appreciation for veterans and their dedicated service.

Armed combat certainly tests one’s faith. In wartime, many – including those on the front lines and those supporting them back home – have found that prayer becomes a lifeline. My flight companion experienced this. He said that even without a church building or a pastor, he knew he could reach God, and today he still keeps a regular “appointment” with the Divine. It doesn’t matter where this communing takes place, he told me. It’s what got him through that difficult time of war and, he feels, brought him safely home.

Though I’ve never been in combat, I could relate to this idea. I like to think of prayer as affirming the power of God, good, that is constantly in operation. It acknowledges God’s presence as our divine Parent, always caring for us. Turning to God can provide inspiration that brings needed comfort and protection in the face of fear or danger.

One of the most oft-repeated psalms in the Bible was written by a man named David, himself a warrior. It provides an inside glimpse into his own talks with God. One verse says: “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil; for You are with me; Your rod and Your staff, they comfort me” (Psalms 23:4, New King James Version).

David’s confidence in God’s protection, even in the worst of circumstances, wasn’t a theoretical concept to him, but was as practical as a child relying on a parent for safety and comfort. The founder of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, shed spiritual light on this psalm by referring to God as divine Love itself: “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for [Love] is with me; [Love’s] rod and [Love’s] staff they comfort me” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 578).

Many veterans who have suffered pain, illness, or loss due to combat continue to seek out that deeper healing love long after they have finished their military service. We can affirm that this same divine Love is always present and available, to bring healing and comfort. No one can ever be separated from God, the divine Life that holds all of its creation safe in its care. Even a small understanding of this spiritual fact can bring freedom from injuries – whether physical or mental – and from the grip of sorrow or frightening images of death.

In addition to doing whatever we can to help veterans in need, we can offer crucial spiritual support, both for those on active duty and those who have long since ended their military service. We can prayerfully know that the tender Christ – God’s love – is reaching them, unimpeded by time and space, with healing effect.

A message of love

Now that’s a wall

A look ahead

Enjoy the rest of your weekend. Come back on Monday. We’ve been tracking the drip, drip of the Mueller investigation into alleged Russian influence on the 2016 US election, and we’ll have a full report on where that stands.