- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for November 20, 2017

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Unless the German Bundestag adds frozen zombies to its agenda, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s bid to form a new government might seem rather less enthralling than your average “Game of Thrones” episode.

Or maybe not.

Why did Ms. Merkel fail to form a coalition? The answer matters from Britain to France to the United States. Voters in those countries are sending a clear message: We’re tired of traditional parties. And their votes are empowering new parties or factions.

In Germany, the country’s second biggest party cratered in the last election. Now it wants nothing to do with Merkel. It wants to take the mantle of outsiders and opposition.

That’s part of the democratic life cycle; elections help parties reinvent themselves. But something else appears to be at work, too. Just as cable TV has splintered into a thousand different channels to meet our interests, so politics appears to be doing the same. The good part is that you get great niche programming, like, well, “Game of Thrones.” The bad part is that fewer of us are actually watching the same things.

Niche politics works the same way. It encourages us to define our identity and interests more and more narrowly. Merkel, like many others, is now struggling to figure out how to square that fractious view of politics with a government that must rule for all.

In our issue today, we look at how one American state is seeking justice, an effort to turn disaster into reform in northern California, and the waning of a pointed tradition in the Middle East.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

As Hillary hovers, Democrats struggle to move on

Hillary Clinton is still a political target because she remains, in many ways, the face of her party. For Democrats, that presents a larger challenge – and opportunity.

More than a year after the 2016 election, Hillary Clinton’s shadow still hovers over the Democratic Party, part of the larger phenomenon of a party with many leaders – and therefore no leader. Some Democrats have been reevaluating former President Bill Clinton’s sexual escapades and Mrs. Clinton’s controversial defense of her husband. President Trump and the Republicans have turned Clinton into a sort of “bogeywoman” – beginning with campaign chants of “lock her up” and continuing to this day with calls for a special counsel to look into her various alleged misdeeds. As the Democrats regroup, they will need to answer an important question: Can they find a way to incorporate Clinton’s perceived positives – including as a role model for women looking to go far in politics – while avoiding her negatives? “There are certainly people still adjusting to the fact that Barack Obama is no longer president, and to the stark difference that Donald Trump gives us,” says Jane Kleeb, chairwoman of the Nebraska Democratic Party. “I think a lot of this struggle to find our footing again is compounding all of that, because there is not one unified voice.”

As Hillary hovers, Democrats struggle to move on

In some ways, the Democrats are on a roll.

First, they beat expectations by easily winning the Virginia governorship earlier this month and nearly taking over the state legislature’s lower house. Now they have a shot at claiming a much more improbable prize: a US Senate seat in a special election Dec. 12 in deep-red Alabama, following allegations of sexual misconduct by Republican candidate Roy Moore.

But Democrats are hardly resting easy. The Clintons have roared back into the headlines, with some in the party now reevaluating former President Bill Clinton’s sexual escapades and Hillary Clinton’s controversial defense of her husband. Mrs. Clinton also caused a recent stir by questioning the legitimacy of President Trump’s election, handing critics an argument that she’s behaving just as she said Mr. Trump would if he had lost.

Elements of the larger context haven’t helped the Democrats: Their aging leaders have become fodder for Saturday Night Live parody. The Democratic National Committee is strapped for cash. And it’s locked in an internal battle between the “Bernie Sanders wing” and the “Hillary Clinton wing,” as it seeks to dig out of years of atrophy under President Obama – and an embarrassing book by former party chair Donna Brazile.

Then there are Trump and the Republicans, who are happily using Clinton for their own purposes. They have turned her into a sort of “bogeywoman” – beginning with the campaign chants of “lock her up” and continuing to this day with calls for a special counsel to look into her various alleged misdeeds.

In short, Clinton’s shadow still hovers over the party, part of the larger phenomenon of a party with many leaders – and therefore no leader. And as the Democrats regroup, they will need to answer an important question: Can they find a way to incorporate Clinton’s perceived positives – including as a role model for women looking to go far in politics – while avoiding her negatives?

“There are certainly people still adjusting to the fact that Barack Obama is no longer president, and to the stark difference that Donald Trump gives us,” says Jane Kleeb, chairwoman of the Nebraska Democratic Party. “I think a lot of this struggle to find our footing again is compounding all of that, because there is not one unified voice.”

The Democrats won’t have a true leader until they have a presidential nominee, and that’s two and a half years away. In the meantime, local party officials are getting used to the cacophony of voices that amount to a collective party leadership that is doing battle – and then at times cooperating – with Trump.

Ask Democrats who their leaders are, and the list is long: from Hillary Clinton, former President Barack Obama, and former Vice President Joe Biden; to Senator Sanders of Vermont (who isn’t even a Democrat, but an independent); to DNC chairman Tom Perez and vice chair Keith Ellison; to Sen. Chuck Schumer of New York and Rep. Nancy Pelosi of California, the minority leaders on Capitol Hill.

“On the one hand, such a long list is great, because it shows the kind of diversity and breadth of our Democratic Party,” says Ms. Kleeb, who was a progressive activist before becoming state party chair. “But on the other hand, it’s not great, because everybody knows that everybody’s fighting.”

Kleeb is a Sanders appointee to the DNC’s Unity Reform Commission, an effort to fix party processes and find common ground among the party’s factions. Last week, Sen. Tim Kaine (D) of Virginia called for the elimination of superdelegates, elected officials who can vote for whomever they want as the Democratic presidential nominee, without regard to the results of primaries and caucuses.

Senator Kaine’s status as an “establishment” Democrat – Clinton’s running mate in 2016, and a former DNC chair – gives his proposal added weight, as the Sanders wing seeks to make the party more “small-d” democratic. The Unity Reform Commission will meet next month and issue recommendations.

Other state party activists are more locally focused. Luis Heredia, a Democratic national committeeman from Arizona, sees opportunity for Democratic pickups in his state’s open US Senate seat, the governor’s race, and the House seat held by Rep. Martha McSally (R). But he agrees that the party’s message needs some work.

“Demographics cannot be destiny,” Mr. Heredia says. “We have a great opportunity with an emerging Latino electorate, with those energized young voters coming in. But in a midterm, you’ve got to give people a reason to vote. Democrats have to run against Trump, but also be bold, and carve out our message.”

In Wisconsin, where Gov. Scott Walker (R) is seeking a third term, state Democratic Party chair Martha Laning has eliminated the term “off year” from her vocabulary.

“We’re calling this the ‘build year,’ ” says Ms. Laning, who has boosted the staff from seven people to 19 since her election in 2015. “Right now, we’re in listening mode. We’re going out and asking people, what is the most important issue to them, and hearing them out.”

None of the state party officials interviewed expressed concern that Clinton could overshadow their efforts in next year’s elections – even in a red state like Nebraska.

“A lot of women and little girls saw Hillary Clinton as a transformative figure, just like many young people and African Americans saw Barack Obama as a transformative figure,” says Kleeb. “So no, we need her. I’m definitely not in the camp saying Nancy Pelosi and others who have been on the national stage need to move aside.”

Democratic pollster Mark Mellman doesn’t see anything unusual in Clinton’s ongoing visibility. “John Kerry went back to being a senator,” says Mr. Mellman, referring to the Democrats’ 2004 nominee. “He didn’t wither away to nothingness.”

He also doesn’t see Clinton trying to exert control over the party. “To my knowledge, she’s not involved herself in any of these internal debates about party processes … or even in policy debates,” he says.

A Democratic strategist, speaking not for attribution, sees the reigniting of debate over Bill Clinton’s presidency – particularly his sexual misbehavior – as a temporary phenomenon linked to the rash of allegations made against men in various spheres of public life, including Trump.

“Let’s be honest, whatever Bill Clinton did, he concluded what the public regards as a successful presidency,” says the strategist. Hillary Clinton’s continued defense of her husband – that he was held to account for his actions – may be uncomfortable for her now, but the moment will pass, he says.

Republicans can be expected to keep demonizing Clinton, as they seek to rev up their voters and avoid a wipeout in the 2018 midterm elections. Most recently, Republicans have been calling for a special prosecutor to look into the so-called Uranium One deal – and alleged links between hefty donations to the Clinton Foundation and the sale of shares of US uranium reserves to a Russian company, a deal approved by the State Department under then-Secretary of State Clinton, along with eight other agencies.

Clinton says the allegations have been “debunked” repeatedly, and that prosecuting her would make the country look like “some dictatorship.” For the GOP, keeping Clinton in the headlines serves an important political purpose.

“One way to keep a very fractured Republican Party together is just to bring up the name Hillary Clinton,” says Seth Masket, a political scientist at the University of Denver.

For Democrats, bringing up Trump serves the same purpose. But even there, the party’s message isn’t uniform. TV ads by billionaire Tom Steyer calling for the impeachment of Trump are opposed by many Democrats.

“Impeachment at this stage, without a smoking gun, looks like a partisan ploy,” says progressive activist Robert Borosage. “It pleases the many liberals afflicted with doses of Trump derangement syndrome, but is seen as irresponsible at best by most everyone else.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Why Oklahoma is rethinking its view of female inmates

Criminal justice is deeply influenced by how a community views those who commit crimes. In Oklahoma, that has had a particular impact on women.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

Oklahoma imprisons more women than any other state – more than double the US average. Behind this approach is a conservative culture that takes a dim view of mothers caught up in drug and alcohol addiction. What might be mitigating factors in other jurisdictions – childhood trauma, domestic abuse – fail to sway prosecutors and judges in Oklahoma. Defendants “are seen as failing as women and, in the eyes of many, are seen as terrible people. They’re mothers who use drugs,” says Susan Sharp, of the University of Oklahoma in Norman. Pushback is coming from reformers who decry the destabilizing effect on families, as well as fiscal conservatives alarmed by the rocketing prison bill. A task force appointed by Republican Gov. Mary Fallin warned earlier this year that Oklahoma would need to find $1.2 billion to add three new prisons by 2026. Last November, voters passed a state ballot question to reclassify minor drug and property crimes as misdemeanors. Still, it will take root-and-branch reforms to reduce the prison population, says Kris Steele, a former Republican speaker of Oklahoma’s House of Representatives who served on the task force. “Oklahoma did not come to have the highest incarceration rate in the country overnight and we’re not going to be able to reverse the trend overnight,” he says.

Why Oklahoma is rethinking its view of female inmates

It was late at night and Laura Richards was behind the wheel, drunk and unhappy, arguing with her husband over who should drive. She was in her late 20s and a mother of two, married to a man who she says abused her.

Finally he got out of the car. “I don’t know what happened, but something snapped,” she says.

Ms. Richards later told police that she had tried to run over her husband – that when she drove the car toward him in her alcoholic haze and he jumped out of the way, it was intentional. She was charged with assault with a deadly weapon.

It was her fourth arrest and it put her on the road to prison in a state that locks up more people per capita than nearly every other. For women, it’s even more of an outlier: Oklahoma’s female rate is the nation’s highest and more than double the average. Both rates are the result of tough sentencing laws, zealous prosecutors, and a lack of alternatives to prisons.

In other states, policies to reduce prison rolls have won bipartisan backing and led to lower overall rates of incarceration, particularly of drug offenders. Oklahoma has tacked the opposite way, taking a punitive approach that echoes that of Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who has blamed lenient sentencing of drug dealers for an uptick in violent crime.

The US is second only to Thailand in its rate of incarceration of women, and the number of women in jail has been rising faster than the general population. In Oklahoma, female imprisonments rose 30 percent between 2011 and 2016.

Most of the women imprisoned in Oklahoma are convicted of low-level drug and property crimes like fraud or bad checks. Women are just as likely to be arrested in other states for these offenses, says Susan Sharp, professor emeritus of sociology at the University of Oklahoma in Norman. “But they’re not going to be sent to prison for 5 or 10 or 20 years,” she says.

“It’s very easy to get a felony,” says Amy Santee, a senior program officer at the George Kaiser Family Foundation (GKFF) in Tulsa. “It’s very easy to be facing a mandatory minimum. Then you quickly get pulled into the criminal justice system and it’s very hard to get out of it.”

Behind this approach is a conservative culture that takes a dim view of mothers caught up in drug and alcohol addiction. What might be mitigating factors in other jurisdictions – childhood trauma, domestic abuse – fail to sway prosecutors and judges in Oklahoma. Defendants “are seen as failing as women and, in the eyes of many, are seen as terrible people. They’re mothers who use drugs,” says Ms. Sharp.

Pushback is coming from reformers who decry the destabilizing effect on families, as well as fiscal conservatives alarmed by the rocketing prison bill for all inmates. A task force appointed by Republican Gov. Mary Fallin warned earlier this year that Oklahoma would need to need to find $1.2 billion to add three new prisons by 2026 to house a projected rise in inmates, in addition to a current prison population that costs more than $500 million a year.

Last November, voters passed a state ballot question to reclassify minor drug and property crimes from felonies to misdemeanors. The change took effect on July 1. Over time, this should mean fewer women sentenced to prison for these offenses, says Kris Steele, who led the campaign for the ballot question.

An accompanying ballot item mandates that money saved should go to treatment programs. Female inmates are much more likely than male prisoners to be diagnosed with serious mental illnesses, according to official data.

Still, it will take root-and-branch reforms to reduce the prison population, given the bias in the system toward punitive sentences, says Mr. Steele, a former Republican speaker of Oklahoma’s House of Representatives who served on the governor’s task force. “Oklahoma did not come to have the highest incarceration rate in the country overnight and we’re not going to be able to reverse the trend overnight,” he says.

An off-ramp before prison

Richards didn’t go to prison. In April, she enrolled in Women In Recovery, a community-based rehabilitation program in Tulsa that has treated hundreds of women facing prison terms for nonviolent offenses. Like Richards, nearly all are mothers caught up in a cycle of abusive relationships, addiction, and petty crime.

Enrollees are provided safe housing, intensive therapy, parenting and career classes, and other tailored services, subject to the approval of a judge. Women In Recovery costs about $19,000 a year per person, slightly less than the price of a prison bed and with a significantly lower risk of recidivism for those that complete it.

Every weekday, Richards takes a bus to downtown Tulsa. On the upper floor of a car park is the entrance to a gray office building where she greets staff and other participants. Inside, the walls are lined with colorful social-justice themed posters; it feels more like a campaign headquarters than a rehab clinic. There are kitchens, playrooms, and a warren of rooms for group and individual counseling sessions.

The aim is not just to help the individual women but also to break a cycle of poverty and crime in families ensnared in the criminal justice system, says Ms. Santee of GKFF, which created the program in 2009 and underwrites most of its costs. “What happens when the mom goes to prison is that the kids really get set on this same pathway,” she says.

Children left with reluctant relatives or put into foster care are at greater risk of neglect and abuse and of turning to drugs and other self-destructive behaviors. Sharp says her surveys of imprisoned women in Oklahoma found high levels of child abuse, both physical and sexual. Nearly all reported that they had suffered domestic violence.

Among the more than 3,000 women currently behind bars in Oklahoma are mothers and daughters serving time in the same state prisons, often for similar drug-related offenses.

Like other states, Oklahoma has drug courts that can divert women to treatment instead of prison. Women In Recovery accepts mothers who don’t make the cut, says Mimi Tarrasch, the program’s director. “If you don’t get into this program, you’re going to prison,” she says.

Door-to-door lawyers

Asher Levinthal’s workday gets a jump-start at 8 a.m. That’s when Tulsa’s county jail updates its booking list and when Mr. Levinthal, an attorney who works in the city’s poorest neighborhoods, can check who has been arrested since yesterday and who has posted bail.

Justice is blind, but a good attorney helps. For the past year, Levinthal’s organization, Still She Rises, has built a legal-aid practice in Tulsa that is exclusively for mothers facing incarceration and helps not only with criminal courts but also child-protection services and other agencies. It’s the first of its kind anywhere in the country. The program is still too new to be able to tell its impact on the recidivism rate of the low-income, African-American population it’s designed to serve.

On a recent morning, Levinthal and a junior attorney climbed into his forest-green sedan and consulted printouts of arrest data. He located three local women who had posted bail; another attorney was at the jail to speak to women still being held there.

At the first two houses, nobody appeared to be home. Levinthal, who wore a gray suit, pushed a leaflet through the letterbox and left. At the third address, a ranch house on a corner lot of patchy grass, a face appeared at the curtained window. The two lawyers walked up to the stoop and rapped on the door.

Silence. A dog barked nearby. “We probably look too much like police or something,” Levinthal muttered.

Eventually the door was opened by an elderly man who said the arrested woman – age 26, charged with reckless and drunken driving – was his granddaughter but that she hadn’t been home. A leaflet was passed on, and the two attorneys headed back to their offices, a rented space in a dilapidated, semi-vacant shopping mall.

Still She Rises is a project of the Bronx Defenders, a nonprofit in New York, and is funded by GKFF. The idea, says Santee, is to improve the legal representation of incarcerated mothers so that they stay out of prison for minor crimes and parole offenses. If Women In Recovery is the final off-ramp before prison, this is a detour.

Still She Rises defends mothers in North Tulsa, a poor, largely African-American community, which is disproportionately represented in Oklahoma’s jails. “It’s always important to go where the need is greatest, and this is a community that has a lot of needs,” says Levinthal.

Forging a new path for families

Richards, who has shoulder-length curly brown hair and green eyes, knows that addictions – alcohol and prescription pills – put her kids at risk. She describes her own childhood in Tulsa as happy and stable; she later found out that her parents both had a history of drug abuse.

While studying to be a dental hygienist she had her daughter at 19, then her son at 22. She worked full-time as an optician and struggled to mend what she calls “a toxic relationship” with her husband. The drinking got worse. But she tried to keep up appearances.

After the car assault in 2015, child services investigated because her daughter was in the backseat. They didn’t take away her children, but the marriage had soured and Richards felt trapped. “I was scared and didn’t know how to get out of it,” she says.

She was also scared of going to prison for assault and other violations, which is why she eagerly accepted a place at Women In Recovery. “I wanted to get away from my husband. I wanted space. I felt like I was being controlled, like a slave,” she says.

Mothers enrolled in Women In Recovery have strictly limited contact with friends and relatives, particularly at the outset, in part to avoid temptations of drugs and alcohol. (Richards says she has been sober for nearly two years.) This also goes for children living in foster care or with relatives, even though the ultimate goal is reunion.

The playrooms at Women In Recovery are brightly painted and stuffed with books and toys. “Share With Others. Say Please. Be Kind,” reads a sign. There’s a large two-way mirror on one wall that allows a counselor to watch reunions between mothers and young children, whose presence can be both a source of joy and of anxiety for these women.

Mothers wear a discreet earpiece so that counselors can guide their play and offer advice on how to deal with tantrums. Afterward there is a debriefing and tips for next time. The next step after these visits is for children to stay overnight with their moms. Eventually they can move in together; program officers also help mothers win back custody of children.

Being based in the community, rather than in prisons, allows the program to show women practical steps to rebuild their lives. “Here are safe places to go. Here are your children’s schools. Many of these moms have never been to their children’s schools, never been to a parent-teacher conference,” says Santee.

Richards, now 31, says she is learning how to be a better parent and to manage adult relationships, particularly with her husband, who shares custody of their children. “I hope they don’t follow down the same path as I did. I hope they can learn from my mistakes,” she says.

Her daughter and son are supportive of her recovery program, she says, and they often stay with her overnight. She isn’t in contact with her husband and doesn’t know if their marriage can be saved. “At some point we’ll figure out what we want to do,” she says.

'I miss my mom'

Tulsa is starting to see the fruits of these initiatives. As more offenders are diverted to Women In Recovery, female prison admissions have fallen by more than half since 2009, even as statewide admissions rose. The program’s completion rate is 68 percent; of these women, recidivism rates after three years are 5 percent, says Ms. Tarrasch.

Under a “pay for success” contract signed in April, Oklahoma has agreed to reimburse Women In Recovery up to $22,584 paid in four installments for each woman that it rehabilitates. The program is expanding to serve 150 women at a time.

This success inspired ReMerge, a diversion program in Oklahoma City for mothers and pregnant women that began in 2011. Nearly all are incarcerated for nonviolent drug offenses. Like Women In Recovery, the program seeks to address underlying mental health issues that have fueled the expansion in female incarceration, says Terri Woodland, the executive director.

“Our prisons have become warehouses for individuals who are struggling with mental health and drug issues,” she says.

Oklahoma City has made less headway, however, in reducing prison numbers. This is because ReMerge is smaller in size – 50 women – and because it’s harder here to find alternatives for women who relapse, says Ms. Woodland. “When a female fails her program (in Tulsa) there’s more of a collaborative effort to keep that individual out of prison,” she says.

At Women In Recovery, two young women sit in the reception room, backlit by the morning sun. Both are new to their program, and as they wait for their classes to start they share war stories of binges, of lost days and nights. One taps her foot on the carpeted floor, 150 beats per minute.

As they talk, another woman paces the window, looking for her mother who is coming to pick her up, perhaps for the first time in a long time. She checks with the receptionist as to program protocol. Does her mother need to come in and sign her out? No, she’s told. It’s fine.

After 10 minutes, a gray-haired woman with a weathered face pulls up. She embraces her daughter at the door, tentatively. Then they turn and head outside into the sunshine.

The two newcomers fall silent and turn their heads towards the window.

“I want my mom to pick me up,” says one.

“I know; I miss my mom,” sighs the other.

They stare out into the blue sky.

Women on the road to recovery

After fires, can N. California make more room for middle class?

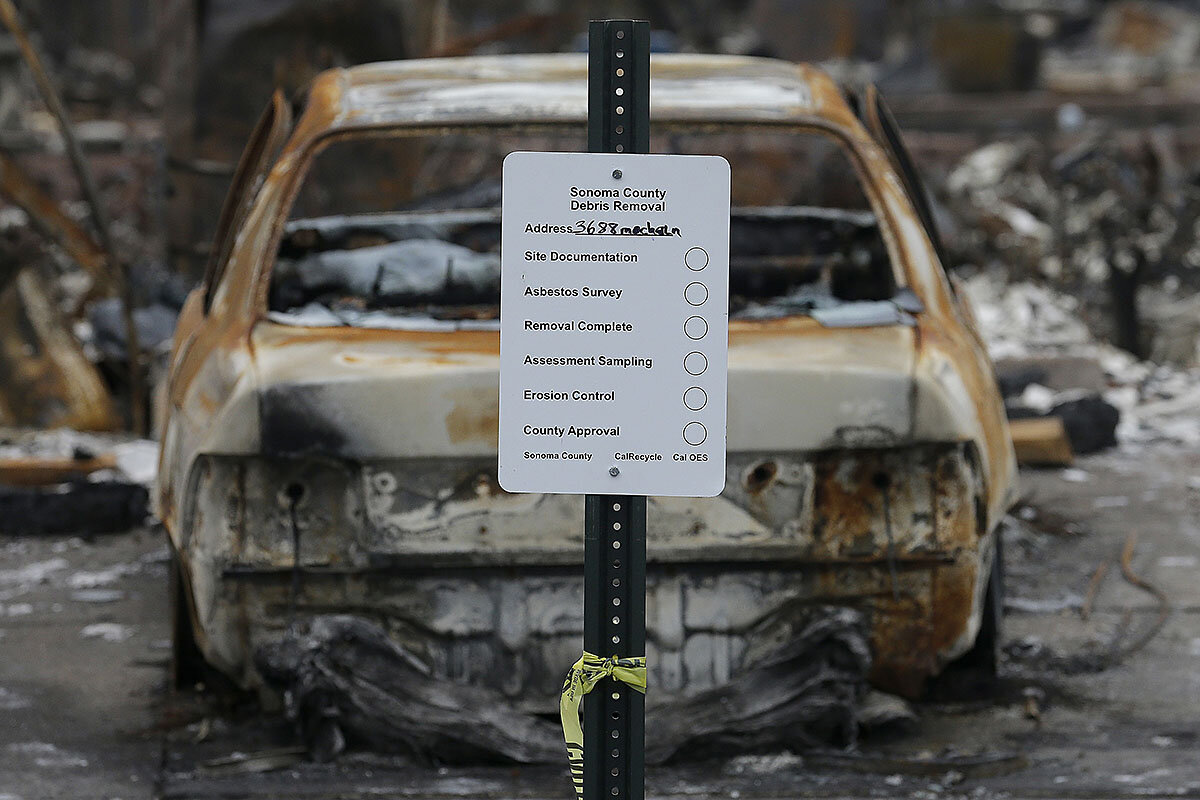

In northern California some people who lost everything to last month’s wildfires still haven’t found a home. But the town of Santa Rosa is choosing to approach the devastation as an opportunity for renewal.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The series of wildfires that engulfed more than a million acres in northern California in early October was among the deadliest in state history. The largest inferno, the Tubbs fire, destroyed 3,000 homes in Santa Rosa alone, squeezing an already strained housing market and leaving middle-class residents with limited options amid rents of as much as $13,000 a month. With tragedy, however, comes opportunity. Before the fire, the area was being divided by a rapidly growing income gap. The disaster exposed the cracks in the community’s infrastructure and spurred residents to support one another. And it has pushed officials to consider rebuilding in a way that accounts for the challenges that faced the region pre-fire. Bill Gittins, an artist who lost his home, says the spirit in Santa Rosa today reminds him of when he and his wife first moved to the city in 1973. Strangers stop each other on the street, wishing each other well. There’s a renewed sense of community that he says was almost lost as the city grew and divided between haves and have-lesses. “It’s kind of a renaissance,” he says. “It’s definitely an opportunity to do things differently – and to do things better.”

After fires, can N. California make more room for middle class?

More than a month after the Tubbs fire burned down his house, Vincent Larsen has yet to find a new home.

As soon as they could, he and his fianceé applied to a series of rentals in Santa Rosa, Calif. – nearly 15 in the past two weeks alone, he says. But competition is fierce. “Everywhere we went there were already eight other people looking at the place,” says Mr. Larsen, an electrician who supplements his income by doing odd jobs.

Because he didn’t have renters insurance, Larsen – who makes about $40,000 a year – lacks the benefit of having an insurance company offer landlords exorbitant rental rates of up to $13,000 a month to put him at the front of the line. Meanwhile he’s living with his fianceé and her 8-year-old daughter at her mother’s house, trying to keep up with the costs of restarting their lives.

“It’s hard right now,” Larsen says.

The series of wildfires that engulfed more than a million acres in Northern California in early October was among the deadliest in state history, killing 42 people and incinerating some 8,400 structures. Preliminary losses are estimated at more than $1 billion. The largest inferno, the Tubbs fire, destroyed 3,000 homes – about 5 percent of the housing stock – in Santa Rosa alone, squeezing an already strained housing market and leaving residents like Larsen with limited options.

With tragedy, however, comes opportunity. Before the fire, the area was being divided by a rapidly growing income gap. The disaster exposed the cracks in the community’s infrastructure and social services and spurred residents to support one another. And it has pushed officials and advocates to consider rebuilding in a way that accounts for the challenges that faced the region pre-fire – as well as the lessons they’re learning about living in a fire-prone area.

“This has been a real learning curve for us in city government who have never seen a disaster like this, ever,” says Santa Rosa Mayor Chris Coursey. “It’s added to our resolve to keep moving forward with our pre-fire housing plans and to deal with this disaster at the same time.”

A search for creative solutions

The post-fire series of ordinances adopted by both Santa Rosa and Sonoma County, which had a 3 percent vacancy rate before the fire, are meant to make it easier for residents to stay in the area as they look for new housing or make plans to rebuild. Under the new measures, homeowners can rent out accessory dwelling units to displaced residents and get fees for building such units waived or reduced. Residents can also park their RVs, trailers, and other vehicles overnight on approved areas where local and state agencies provide services like showers and warming stations.

Officials are also trying to think more creatively about how to rebuild. Santa Rosa, for instance, is looking to partner with Sonoma Clean Power – the city’s main electricity provider – to help residents rebuild structures that would meet the state’s 2020 standards for energy efficiency, Mayor Coursey says. “We can have a swath of our community be net-zero energy consumers when this is done,” he says. The city is also hoping to get support from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to construct permanent housing on emergency sites, the mayor says.

At the county level, Permit Sonoma – in charge of processing resident applications to rebuild in the county’s unincorporated areas – plans to create a new center solely to serve fire survivors. A housing task force, made up of local, state, and federal representatives, has also been appointed to come up with ways to cut down costs for long-term urban development.

“Everything’s on the table, and everyone’s thinking about creative solutions to develop more housing,” says Maggie Fleming, a communications manager for the county.

The new policies largely align with what researchers say are best practices for short- and long-term responses to disasters.

Who pays?

Some lawmakers are calling out the federal government for its lack of support. On Friday, the White House requested from Congress $44 billion in supplemental disaster aid – none of which is meant to help California recover from the wildfires. “Folks throughout California were ravaged by this fire, and we should ensure they get the help and support they need,” Rep. Mike Thompson (D) of Napa Valley told the Los Angeles Times on Sunday.

And not everyone is immediately benefiting. Since losing the two-bedroom house he and his family were renting in Santa Rosa’s Fountaingrove neighborhood, Larsen has struggled to secure any kind of aid from nonprofit or government agencies. He’s in a dispute with his former landlady over his security deposit. And he says that since the fires, he’s spent close to $6,000 in clothes, shoes, food, and other necessities for himself, his fianceé – a full-time nursing student – and her daughter.

“When you have nothing, you’ve got to buy,” Larsen says. “It’s such a vulnerable and fluid situation.”

What keeps Larsen going, besides his family, is the community. Days after he and his family evacuated, an uncle who lives in the area set up a PayPal account to receive donations on their behalf. Larsen has pitched in to help others, helping to hook up houses with generators when the power was out and put out spot fires across his old neighborhood.

“People have been doing fundraising, really giving back,” he says. “They’ve been dynamite.”

Bill Gittins, an artist who also lost his home in the fires, says the spirit in Santa Rosa today reminds him of what it was like when he and his wife first moved to the city in 1973. Strangers are stopping each other on the street, wishing each other well. There’s a renewed sense of community that he says was almost lost as the city grew and progressed. “It’s kind of a renaissance,” he says.

Both Larsen and Mr. Gittins say that their losses have reinforced their values and led them to reevaluate their priorities. “It’s definitely an opportunity to do things differently. And to do things better,” Gittins says.

Others apply the sentiment to a broader frame.

“The wildfires have put our community in a position to start a conversation to solve this crisis and provide affordable housing for all of our residents – both those displaced by the fires and those who were experiencing homelessness and displacement before the fires,” says Shelby Harris, a Santa Rosa native who works with Social Advocates for Youth, a nonprofit that serves homeless youth in Sonoma County. “There are a lot of people here who care about the community.”

Points of Progress

A steady forward march for captive elephants

Changes in how zoos worldwide are treating elephants points to a broadening desire to be humane.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

Last week, the welfare of wild elephants was put in high relief by public furor around the proposed lifting of a ban on allowing trophies from African elephant hunts into the United States. The plight of captive pachyderms, too, is winning worldwide awareness. And that has begun to translate to changes in zoo policies. The shifts are gradual, experts say, and range from a new willingness to improve enclosures to the shutting down of enclosures altogether. Besides the ending of The Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus’s elephant act last year, exhibits have been shuttered at facilities in Georgia, San Francisco, and Detroit, with their elephants sent to sanctuaries. The US isn’t alone: India’s Central Zoo Authority prohibited elephants in zoos or circuses in 2009, sending 140 captive elephants to national parks or reserves. And Japan is studying the living conditions of elephants in its zoos. “There are indications that some change is happening,” says Jonathan Balcombe of the Humane Society Institute for Science and Policy. “[But] there is more … we could be doing.”

A steady forward march for captive elephants

When Ulara Nakagawa saw the 69-year-old elephant Hanako at Tokyo’s Inokashira Park Zoo in 2015, she knew she had to do something.

“At first glance, I mistook her for a statue. Then I saw her move a bit, and realized it was living creature. I was devastated,” says Ms. Nakagawa. Hanako had lived alone in a small concrete enclosure almost her entire life, leading some to call her “The Loneliest Elephant in the World.”

Nakagawa started an online petition to send Hanako to an elephant sanctuary. But when it was just shy of half-a-million signatures in March 2016, Hanako died. Nakagawa started the organization Elephants in Japan in Hanako’s honor to improve elephants’ lives.

Nakagawa’s urgent efforts mirror a growing worldwide awareness of the plight of captive pachyderms that is starting to translate to changes in zoo policies. Those shifts are gradual, experts say. They run from a growing willingness to improve enclosures to the shuttering of such enclosures altogether.

“There are indications that some change is happening. [But] there is more … we could be doing,” says Jonathan Balcombe, an expert on animal behavior and a director with the Humane Society Institute for Science and Policy. “We’re in an era with an unprecedented level of moral concern for the wellbeing of animals.”

And the fight against performing captive elephants has seen specific success, say experts like Mr. Balcombe and Ed Stewart, president of the Performing Animal Welfare Society (PAWS).

The 146-year-old Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey traveling circus ended its elephant act in 2016 due to activist protests, and then shut down production completely earlier this year due to declining ticket sales. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed the Elephant Protection Act into law last month, making New York the second state after Illinois to legally prohibit the use of elephants for entertainment, such as circuses. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio signed a similar citywide bill this summer.

Mr. Stewart says public concern about elephants is “accelerating” every day.

“With social media now you can figure out what is going on almost anywhere. The underpinning of captivity is falling apart,” says Stewart. “I think in 20 years we’ll look back and think ‘Wow, we locked animals up in cages for no reason.’”

Between 2004 and 2005, the Chehaw Wild Animal Park in Georgia, the San Francisco Zoo, and the Detroit Zoo all ended their elephant exhibits for ethical reasons, sending their combined six elephants to sanctuaries. The Buttonwood Park Zoo in New Bedford, Mass., the Bronx Zoo in New York, and the Point Defiance Zoo and Aquarium in Tacoma, Wash., all say they will end their elephant exhibits when their current elephants pass away.

And the US isn’t alone: India’s Central Zoo Authority prohibited elephants in zoos or circuses in 2009, the country’s 140 captive elephants were transferred to national parks or reserves. In 2013 the Toronto Zoo ended its elephant program and transferred two African elephants to the PAWS facility in San Andreas, Calif. And just last year the Mendoza Zoological Park in Argentina transferred four elephants to a sanctuary in Brazil.

The tide could be turning in Japan as well, says Keith Lindsay, a Canadian-British conservation biologist who has studied elephants for more than 30 years.

Inspired by Nakagawa’s story of Hanako, Dr. Lindsay partnered with Elephants in Japan and the Canada-based organization ZooCheck to publish a report on the living conditions of 14 other solitary elephants in zoos across the country.

“This concern over one particularly tragic case opens the window on wider issues of elephant keeping in Japan, as the public grows ever more aware of the need to consider the welfare of all animals,” says Lindsay in his June report. He is hopeful that international attention from the 2020 Tokyo Olympics will pressure the remaining 51 Japanese zoos with elephants to either improve living conditions or end their exhibits.

“Visitors from the outside will see the animals and comment on it. It’s an added incentive for Japan to do something,” says Lindsay. “I’m cautiously optimistic.”

Kaori Sakamoto, a Japan-based advocate for zoo animals, told The Japan Times that many zoos have already read Lindsay’s report and started making modifications.

The dagger-maker’s art: preserving a Bedouin craft

For generations, a steel blade has symbolized manhood and honor in the Middle East. Now, the disappearance of Bedouin daggers speaks to a changing society.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Taylor Luck Correspondent

For centuries, Bedouin tribesmen have lived and died by their shibriyas - simple, workmanlike daggers good for all sorts of tasks. But the art of shibriya-making is dying out; the few blacksmiths who learned it from their fathers, who had learned it from their fathers, want their own sons to do easier and better-paid work. More than 150 years ago, one of Abdulrazzak Abu Mohaisen’s forefathers learned modern blade-making as a conscript in the Ottoman Army in Crimea. He brought his new skill home to Jordan and revolutionized the manufacture of daggers. Mr. Abu Mohaisen is still in the shibriya business, but fewer and fewer Bedouin live the traditional desert life that demanded a dagger, new laws forbid carrying the weapon in the cities, and cheap Chinese imports are fooling tourists. “If we lose the Bedouin,” Abu Mohaisen laments, “the world will lose the shibriya.”

The dagger-maker’s art: preserving a Bedouin craft

Nawwaf Khazaeeya lives each day on a knife’s edge.

From his tent near the livestock souq in Madaba, at the edge of the central Jordanian desert, Mr. Khazaeeya spends his day pounding out steel.

“This is more than a knife,” Khazaeeya says. “This is life and death.”

Khazaeeya belongs to one of the last families of shibriya makers, carrying on an ancient craft handed down through generations that has armed Bedouin nomads for centuries.

Yet modern bans on weapons, the Bedouins’ increasingly urban lifestyle and an influx of cheap Chinese imitations are undermining the market for traditional shibriya. Dagger-makers warn they may soon have to pack up their hammers and anvils for good.

Should the dagger-makers disappear, so too will a symbol of Bedouin life, honor, and independence. The daggers are both functional art and potent symbols of Middle Eastern manhood that have underpinned the honor code and culture that once united Arab tribes across the Levant and the Gulf.

The shibriya has also been a status symbol, and until recently was worn by tribal judges, sheikhs, princes, and warriors alike.

“The shibriya was a sign of respect, strength, and stature,” says Nayef Nawiseh, a Jordanian historian. “If you were a man, you wore a shibriya.”

Ottoman knowhow, Bedouin skills

The name shibriya comes from the Arabic shibir, a unit of measurement equal to an outstretched adult hand from thumb to finger – some five to six inches long, the approximate length of the blade.

Unlike the curved, ornate daggers of Yemen and Oman, the shibriya is a straight, workmanlike blade made for the rough-and-tumble of daily Bedouin life. Not a decoration but a tool, it is designed to be easily drawn, to cut through canvas and rope, to shear sheep – and to kill.

While Bedouins have been carrying crude versions of the shibriya for centuries, the dagger as it is known today dates back to the 1850’s, when the Ottoman emperor, fighting the Crimean War, conscripted thousands of Arabs into his army.

Among the recruits was Mohammed Abu Mohaisen, from what is now southern Jordan, who was drafted into the Ottoman army’s armaments division and spent years mastering Ottoman blacksmith skills, crafting bayonets, muskets and swords.

When the war ended, blacksmiths like Mr. Abu Mohaisen were sent back to what is today Jordan. There they began producing the shibriya dagger for local Bedouins, updating the desert weapon using Ottoman knowhow.

Abu Mohaisen introduced the now-distinctive angle to one edge of the blade; that made it better for domestic purposes such as cutting fabric, chopping vegetables, or trimming the fat off meat, and also more lethal as a weapon.

In other innovations, he gave his blades copper or silver sheaths, and made handles out of ivory and goat horn.

Today, Abu Mohaisen’s descendants carry on the family craft near Amman’s Roman theater, hammering out blades by hand in the same way the Ottomans did nearly two centuries ago.

Recycling and resourcefulness have been key to the shibriya’s longevity. Abu Mohaisen’s father and grandfather used discarded railroad track from the Hijaz railway for the steel for their blades. Now Abdulrazzak Abu Mohaisen and his four brothers use the coil and suspension springs from old cars and trucks, among other sources.

Working on his own, Abdulrazzak can make two or three daggers a day, and sell each one - including a lifetime warranty – for up to $50 to tribesmen living as far away as Syria, Iraq and Gulf countries.

There is some art involved.

On the sheath, shibriya makers carve floral or geometric designs; on the pommel they stamp tribal symbols, Allah or the Jordanian royal crown; on the hilt they embed gemstones - blue turquoise to ward off the evil eye, brown aqeeq quartz for good luck. The Abu Mohaisen family engraves customers’ names on the face of the blade, in addition to their family stamp.

But it is, first and foremost, a weapon.

“This is a simple weapon from a simpler time,” Abu Mohaisen says as he swiftly draws a dagger from its sheath. “It was built for strength, toughness and endurance, not for cosmetics.”

An ancient weapon in a modern world

Modern law has reduced the shibriya’s prominence in daily life. In the 1950’s, Jordan passed a penal code barring the carrying of weapons in urban areas; the knife soon disappeared from the streets of Amman and other cities.

In today’s Jordan, only ceremonial palace guards and elite desert forces are allowed to wear them in town in public. Tribal judges and sheikhs wear them at social gatherings.

But outside Jordan’s cities, in Bedouin towns and villages, the shibriya is still very much part of daily life, an accessory second only to the mobile phone.

In the town of Maan, 135 miles south of Amman at the edge of Jordan’s southern desert, grocers sell the daggers from large plastic Tupperware bins next to their cash registers, as if they were candy.

One shopkeeper showed a video on his phone of a man slaughtering three camels with a shibriya to serve for dinner at a recent wedding. It was not pretty, but it was effective: The shibriya made surgically precise cuts, bringing the beasts down instantly.

Today, Jordan’s dagger-makers face a difficult market. Fewer than five percent of Jordanians still live the Bedouin way of life, so most of Abu Mohaisen’s customers are tribal sheikhs or foreign embassy employees looking for a unique gift. US diplomats are particularly good customers.

A flood of imported imitation daggers selling for as little as seven dollars apiece has taken over the tourist market; visitors are often unable to distinguish aluminum Chinese models from the real thing.

Abu Mohaisen and Khazaeeya are reluctant to train their children in the ways of dagger-making. Instead, they want them to go to university and choose a profession offering security, health care and retirement benefits. With many of Jordan’s Bedouins choosing desk jobs over sheep herding, the craftsmen fear their days are numbered.

Once nobody is living the desert life any more, there will be no demand for the dagger, they say.

“As long as there are Bedouin in this world, there will be a need for us,” says Khazaeeya.

“But if we lose the Bedouin, the world will lose the shibriya."

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Time to tally up Africa’s progress in governance

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

Zimbabwe’s progress on demanding accountability from its ruler is a mark of hope for the African continent. Africa-watchers find steady if sometimes erratic progress – despite the fact that about 40 percent of Africa’s population is under 15 years old and lives in extreme poverty. And overall, Africa is doing better on the quality of its governance, according to a Nov. 20 report by the Mo Ibrahim Foundation. In the past 10 years, 40 of Africa’s 54 countries have improved on indexes that track government effectiveness and political participation. Last year, Africa achieved its highest score in 11 years of tracking. With a peaceful and constitutional change of power, Zimbabwe could add to this record. The continent has overwhelming problems. But progress already made on governance helps make way for further progress.

Time to tally up Africa’s progress in governance

One charge thrown at President Robert Mugabe as he faces impeachment in Zimbabwe is that “he can hear the voices of the people, but is refusing to listen.” In Africa’s long journey toward democracy, one sign of success is when a ruler’s own party demands such accountability. Zimbabwe’s progress on that point is a mark of hope for the continent.

Overall, Africa is doing better on the quality of its governance, according to a Nov. 20 report by the Mo Ibrahim Foundation. In the past 10 years, 40 of Africa’s 54 countries have improved on indexes that track government effectiveness and political participation. Last year, Africa achieved its highest score in 11 years of tracking. With a peaceful and constitutional change of power, Zimbabwe could add to this record.

Other Africa-watchers find steady if sometimes erratic progress despite the fact that about 40 percent of Africa’s population is under 15 years old and lives in extreme poverty.

In a new book, “Making Africa Work: A Handbook,” a group of scholars writes: “Many African leaders have responded to the overwhelming wishes of their citizens by changing from autocratic regimes – the preferred system of government from the 1960s to the 1980s – to electoral democracy.”

The Institute for Security Studies, a South African think tank, finds popular support for democracy is likely to remain strong. It also notes that Africa is becoming more democratic despite the generally low levels of per capita income.

In October, the World Bank reported that sub-Saharan Africa had implemented 83 reforms in the past year to create jobs and attract investment, a record for a second consecutive year. “In 2003, it took 61 days on average to start a business in the region, compared to 22.5 days today,” the bank stated.

In July, the continent-wide African Union marked the first African Anti-Corruption Day, which at least helps recognize one major drag on economic growth and governance. Africa has also shown progress on many indexes of well-being, such as infant mortality. Yet even though it has half the world’s arable land, it remains dependent on food imports.

The political events in Zimbabwe, while historic for that country, simply reflect a wider shift in Africa. The continent has overwhelming problems but progress already made on governance helps make way for further progress.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Who shall be greatest?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Susan Tish

In Zimbabwe, Kenya, and elsewhere, we see a struggle to answer the age-old question “Who shall be greatest?” But it’s also become clear that posing this question doesn’t lead to answers or progress. With his words and his actions, Christ Jesus showed that only through humility and self-sacrifice can one effectively lead and serve as a model of behavior for others to emulate. And everyone is capable of doing this, because we are God’s children, created to express love and integrity. When we see that everyone shares this common heritage, it becomes more natural for us to work together in harmony. Humble leadership and a spirit of brotherly partnership can turn around even the most difficult challenges. So much good can be accomplished when we recognize our true brotherhood and imbibe the spirit of divine Truth and Love.

Who shall be greatest?

Across the globe, stagnation and even crises in government are all too common refrains because of an ever widening divide between opposing political groups or individuals. In Zimbabwe, Kenya, and elsewhere, we see a struggle to answer the age-old question “Who shall be greatest?” But it’s also become clear that posing this question doesn’t lead to answers or progress.

There was a time during Christ Jesus’ ministry when he explained this point to his 12 closest disciples, who were arguing over who would be the greatest. Jesus said: “Who is more important, the one who sits at the table or the one who serves? The one who sits at the table, of course. But not here! For I am among you as one who serves” (Luke 22:27, New Living Translation). With his words and his actions, Jesus reminds them that only through humility and self-sacrifice can one effectively lead the people and serve as a model of behavior for others to emulate. For instance, in the spiritual laws that he laid down in the Beatitudes he promises that “God blesses those who are humble, for they will inherit the whole earth” (Matthew 5:5, NLT). His example and the divine laws of love that he gave us continue to be effective and powerful agents for change 2,000 years later: Love and humility strengthen leadership and truly prove our worth.

Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of The Christian Science Monitor, explained in 1902 that “competition in commerce, deceit in councils, dishonor in nations, dishonesty in trusts, begin with ‘Who shall be greatest?’ ” Speaking of God as divine Love, she said, “To live and let live, without clamor for distinction or recognition; to wait on divine Love; to write truth first on the tablet of one’s own heart, – this is the sanity and perfection of living, and my human ideal” (“Message to The Mother Church for 1902,” pp. 4 and 2).

From the inspiration of Christ Jesus’ teachings, she taught that it is natural for each of us – and for our leaders in government – to be led by divine Truth and Love, which are synonyms for God. In the book about her discovery of Christian Science she wrote that in fact every one of us is “conceived and born of Truth and Love” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 463), so we inherently express the spiritual qualities that come from God in being truthful and loving.

When we see that we share this common heritage as God’s children, it becomes more natural for us to work together in harmony. No single individual or ideology shall be greatest, but God, divine Principle – which is above all, governing all. Ruled by the inspiration that comes from divine Truth and Love, we are guided by God in times of crisis. And being led by God to be honest and loving in this way makes for truly inspirational leadership.

Humble leadership and a spirit of brotherly partnership can turn around even the most difficult challenges. But the spirit of brotherhood begins with each of us. Rather than seek individual distinction or assert one’s own agenda, let each of us strive to see that, as Mrs. Eddy writes on page 3 of her 1902 address to The Mother Church, “right is the only real potency; and the only true ambition is to serve God and to help the race.” So much good can be accomplished when we recognize our true brotherhood and imbibe the spirit of Truth and Love.

Adapted from a Christian Science Perspective article published May 20, 2016.

A message of love

Trying to move on in Zimbabwe

A look ahead

Thank you for reading today. Tomorrow, we'll be looking at Beto O'Rourke and Will Hurd, Texas legislators who come from different parties but gained fame by taking a road trip together. We'll look at how their friendship has played out in a state that, like many, views across-the-aisle relationships with suspicion. Please join us.