- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for February 7, 2018

It’s not the stuff of big dreams: an African-American sharecropper family struggling in the Jim Crow South. Illiterate parents. Ten kids.

Yet, as Dorothy Ngongang told The Washington Post, “Our mother … encouraged us to learn or ‘get something in our heads that no one could take from us.’ ”

They listened. And two years ago, the siblings, who hold seven college degrees and three master’s, bought the land where they once picked cotton – and, separately, the large house opposite that once represented a life far from their reach. They played as children with its white owner, Peggy Wheeler McKinney, who reached out when she wanted to sell. They celebrated Christmas there.

As Sharon Austin, director of African studies at the University of Florida, notes in an essay, “Progress has been made. Just not as much as many of us would like.” Witness, for example, actress Jessica Chastain’s shock when she heard the salary Oscar nominee Octavia Spencer initially accepted for their upcoming movie.

But, Ms. Austin adds: "To put it in [Martin Luther King Jr.’s] words, 'Lord, we ain’t what we oughta be. We ain’t what we want to be. We ain’t what we gonna be. But, thank God, we ain’t what we was.' ”

That’s because of the powerful mental seeds planted by people like Ms. Ngongang’s mother. “I felt I wasn’t going to be there picking cotton my whole life,” Ngongang said. She was right.

Now to our five stories, showing equity, innovative thinking, and the democratic process at work.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Memo wars: When secrets get out, what happens next?

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court at the heart of the "Nunes memo" debate is controversial at best. That makes the discussion of transparency and the protection of intelligence sources particularly complicated.

Will the release of the so-called Nunes memo have some unintended consequences? The document – drawn up by aides to the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, Republican Rep. Devin Nunes of California – accuses the FBI of abusing its surveillance powers to get the Russia investigation rolling. In doing so, it mentions dates and targets of US electronic eavesdropping approved by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court. Warrants issued by the court specifically, and US eavesdropping in general, are usually among the most closely held of US secrets. Some experts worry that making such activities public could damage the relationship between the intelligence community and congressional oversight committees, discourage foreign spies from sharing their own acquired secrets, and complicate prosecutions that draw on evidence gathered under these secret warrants. And it’s possible that the Democratic attempt to rebut the Nunes memo could make these problems worse, if it reveals yet more classified information.

Memo wars: When secrets get out, what happens next?

The United States government holds tight to its classified information. Consider this: The last US secret documents from the World War I era were not declassified until 2011. They dealt with the ingredients and methods for producing invisible ink of such high quality it could be used by spies. It took a century until technological advances rendered the old recipe obsolete, then-CIA Director Leon Panetta said at the time.

Given that culture of official secrecy, some current and former US intelligence and law enforcement officers find it surprising, even shocking, that the so-called “Nunes memo” has become public. The memo, written by aides to House Intelligence Committee Chairman Rep. Devin Nunes (R) of California, accuses the FBI of abusing surveillance powers to get the Russia investigation rolling. It contains information about decisions made by a secret court that oversees spying on the communications of Americans in national security investigations.

The Feb. 2 release of the congressional memo could have wide-ranging unintended consequences, say experts. It could chill relations between the intelligence community and Capitol Hill, make allied intelligence agencies less eager to share their own secrets, and amp up demands by some defendants to use Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court documents in their own trials.

“I’m concerned about the revelation of things that go before the FISA court ... we’re talking about the most sensitive things the government does on behalf of the American people,” said former Attorney General Eric Holder at a Monitor breakfast for reporters on Feb. 7.

A Democratic memo rebutting charges of FBI bias could push this process along, depending on what it says, and if and when President Trump approves its release.

The White House is “undergoing the exact same process that we did with the previous memo, in which it will go through a full and thorough legal and national security review,” said White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders on Tuesday.

The central charge of the Nunes memo is that the FBI relied too heavily on opposition research funded by the Hillary Clinton campaign in its application to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) for a warrant to eavesdrop on the communications of Carter Page, who served for a time as a foreign policy adviser to the Trump campaign.

The ranking Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee, Rep. Adam Schiff of California, has drawn up a 10-page document intended as a rebuttal to this assertion. It reportedly notes, among other things, that the court application did, in fact, say that the source of the information in question came from a partisan source, though that acknowledgement came in a footnote. It says that the application contained confirmations from other sources, notes that it was extended by the court at least three times, and points out that Mr. Page first attracted the FBI’s attention as early as 2013. The bureau at that time warned him it had information that Russia had targeted him as a potential US source.

The full House Intelligence Committee has voted to release the Democratic rebuttal. The president is expected to approve its release as well – but Democrats fear he will redact embarrassing or damaging information from the document under the guise of security concerns.

The political argument over release has thus been flipped over since last week. In regards to the Nunes memo, Republicans argued for “transparency,” while Democrats worried about revealing secrets. On the Schiff rebuttal, the White House has said it will consult with the FBI and Justice Department as to whether release is safe. Democrats are the party pushing for more information to be made public.

“Everyone’s arguments ... have been somewhat complicated,” says Andrew Wright, an associate professor at Savannah Law School and a founding editor of the legal blog Just Security.

Experts note the Nunes memo has already revealed things the FBI would have much preferred be kept under wraps. Carter Page and his attorneys now know the exact dates surveillance began and was renewed, for instance. That gives them insight into what law enforcement knows, and what it may not know. More important, the people Page was talking to know what the FBI has on them in terms of electronic surveillance, as well.

One of the most important inadvertent consequences here may be damage to the relationships that US intelligence has with allied agencies around the world. The lesson foreign spy chiefs may take from this is that Congress may declassify information shared with the US, despite promises of secrecy from the American intelligence community. Such information can be crucial – both Australia and the Dutch have reportedly passed along tips highly useful to the US investigation into Russian influence in the 2016 election.

“To me in some ways the biggest consequence of this is that other countries may be reticent to share information with us if they feel it is going to be handled this way,” says Dr. Wright.

Similarly, the relationship between the US intelligence community and congressional intelligence committees may be damaged. These panels were set up in the late 1970s to provide an outside review of CIA and NSA activity. The understanding was that the panels could have access to virtually all US secrets, in exchange for treating the information with care and following strict security measures of their own. But disputes over access still occur – and now they may become more frequent, and perhaps more intense.

Finally, the disclosure of some Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) information may simply create press and public demands for more of the same. Already, The New York Times has filed a motion with the court asking for full disclosure of all material dealing with Carter Page wiretapping applications. Given the partisan arguments now occurring with their roots in these documents, “disclosure would serve the public interest,” the Times argued in its motion.

Right now, defendants in cases where material derived from FISC-approved wiretaps is being used against them don’t get to review the application for the court warrant, or any application documents. The Nunes memo may open a crack that allows such information through.

“I assume Carter Page, if he is charged, will successfully be able to win review of his FISA application ... that may mean he doesn’t get charged or, if he does, Mueller has to bend over backwards to avoid using FISA material,” wrote independent surveillance expert Marcy Wheeler on her blog Emptywheel last week.

The next step in this process – release of the Schiff memo – could come within days. The Democratic Mr. Holder, for his part, hopes Mr. Trump allows the document to go forward with only minimal cuts.

“I’m pretty sure that Adam Schiff, in that memo, would not reveal inappropriate things,” Holder says.

Share this article

Link copied.

Monitor Breakfast

Eric Holder emerges in Democrats’ strike against gerrymandering

Former Attorney General Eric Holder made news at a Monitor breakfast today by demurring when asked if he might run for president. More important for him was the fight against partisan gerrymandering.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The 2020 Census is coming soon, meaning redistricting – the drawing of boundaries for state and federal legislative districts – isn’t far behind. That may sound like a dry bit of government bookkeeping, but redistricting has become a hot topic for Democrats trying to wrest control of the US House from Republicans. It's also the subject of two current Supreme Court cases. Leading the Democratic initiative on redistricting is former Attorney General Eric Holder. In his view, the fair formation of voting districts goes to the very heart of representative democracy. “We have a system now where politicians are picking their voters as opposed to citizens choosing who their representatives are going to be,” Mr. Holder said Wednesday, speaking at a press breakfast hosted by The Christian Science Monitor. “And it's a fundamental affront to our system of democracy.” For Holder, a career lawyer in both the private and public sectors, political activism is a new world. He calls fundraising “interesting,” and leaves it at that. As for whether he might run for office himself – possibly even president – he said Wednesday, “We’ll see.”

Eric Holder emerges in Democrats’ strike against gerrymandering

There’s no doubt that Democrats are energized for this November’s midterm elections. But there’s more at stake than just the partisan control of state and federal offices for the next few years.

Democrats are laying plans for a political reset – and, they hope, a more level playing field – with an impact that would reach all the way to 2031.

Leading the charge is a perhaps-unlikely figure: Eric Holder, attorney general under former President Barack Obama. With Mr. Obama’s help, he’s tackling the seemingly dry issue of redistricting, the drawing of boundaries for state and federal legislative districts.

In fact, it’s a hot topic, with the 2020 Census coming soon, followed by redistricting in 2021, and three cases at the Supreme Court. And in Mr. Holder’s view, the fair formation of voting districts – and fighting partisan gerrymandering – goes to the very heart of representative democracy.

“We have a system now where politicians are picking their voters as opposed to citizens choosing who their representatives are going to be,” Holder said Wednesday, speaking at a press breakfast hosted by The Christian Science Monitor. “And it’s a fundamental affront to our system of democracy.”

Holder is chairman of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee (NDRC), a group that launched last year to help elect Democratic state legislators, governors, and other elected officials in key states as redistricting approaches, and to promote reform of the process.

The NDRC has targeted 12 states, some of them so-called GOP “trifectas” – states where both legislative chambers and the governor’s office are controlled by Republicans. It is also trying to prevent others from becoming trifectas.

For Holder, a career lawyer in both the private and public sectors, political activism is a new world. He calls fundraising “interesting,” and leaves it at that. As for whether he might run for office himself – possibly even president – he said Wednesday, “We’ll see.” He’ll decide by the end of the year, he says.

Holder’s own high profile, as well as that of his friend Obama, is helping with fundraising. In 2017, the NDRC and its affiliated entities raised $16 million, out of an eventual goal of $30 million. It also contributed $1.2 million toward Democrat Ralph Northam’s winning gubernatorial race in Virginia last November.

In Virginia state legislative races, the Democrats defied expectations, nearly retaking control of the lower chamber – an effort Holder helped through fundraising and campaign appearances.

Democrats also scored a victory Monday in Pennsylvania when the US Supreme Court declined to block a state high court ruling that threw out the state’s congressional map over partisan gerrymandering – the drawing of political boundaries to favor one party over another. Thirteen of Pennsylvania’s 18 members of Congress are Republican, even though registered Democratic voters in the state outnumber registered Republicans.

Two cases before Supreme Court

Partisan gerrymandering also lies at the heart of two cases before the US Supreme Court – one brought by Democrats in Wisconsin, the other by Republicans in Maryland. The cases show that partisan gerrymandering is an equal-opportunity practice. How the justices rule could reshape the conduct of US elections.

When asked about Maryland, where it’s the Democrats who are blamed for engaging in partisan gerrymandering, Holder points out that it’s just one congressional district at issue.

“You could talk about that one district, but we’re focusing on states that have had substantial gerrymandering problems,” Holder says, naming Texas, Wisconsin, and North Carolina as the most egregious examples.

A lawsuit over North Carolina’s congressional map is working its way through the courts. And last month, the Supreme Court agreed to hear a Texas case on racial gerrymandering.

Holder says he and Obama plan special outreach to black voters in the run-up to the midterms.

But in general, Democrats can only get so far in creating more favorable maps via redistricting and legal action, experts say. They need to do the shoe-leather work of running for and winning seats in the state legislatures that draw the maps in most states every 10 years.

Belated realization

During Obama’s presidency, the party let its down-ballot efforts atrophy, and suffered a net loss of nearly 1,000 state legislative seats. The result has been stark: In 2008, Democrats controlled almost 60 percent of state legislative bodies. Today, Republicans have nearly 70 percent.

“Democrats finally came to the realization that they’re at a bit of a disadvantage on the map,” says David Wasserman, an expert on redistricting and gerrymandering at the nonpartisan Cook Political Report.

Part of that is attributable to redistricting, he says. In 2010, the last census year and Obama’s first midterm, the Republicans won big across the board – a “shellacking,” as Obama put it, in the big tea party wave.

But even in a wave election, which the Democrats are hoping for this November, targeting races is key. In 2010, the Republican program REDMAP – the Redistricting Majority Project – targeted states where just a few seats could shift the balance of a state legislative chamber to Republican control in time for the 2011 redistricting. That’s part of what NDRC is doing in 2018 on the Democratic side.

“Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery,” says Matt Walter, president of the Republican State Leadership Committee, which developed REDMAP.

Another challenge for Democrats is that their voters are clustered in cities and towns and on the coasts, which hurts their chances of winning power, Mr. Wasserman notes. The trend toward partisan “sorting” – people choosing to live near like-minded people – means there’s only so much Democrats can do in redrawing district lines.

“The truth is, gerrymandering compounds sorting,” says Wasserman. “When we’ve had a balkanization or a polarization of voters on the map to the degree we’ve seen in the last 20 years, it becomes easier for partisans drawing the maps to create safely Democratic or safely Republican seats.”

Impact on polarization

Safe seats often lead to the election of members who don’t feel the need to work across the aisle, contributing to polarization. Elections in such districts are often decided in the primaries, which are dominated by the most hard-line partisan voters.

So the creation of more competitive congressional districts could ease polarization, at least somewhat.

Citizen-led efforts to reform redistricting are under way in seven states, according to the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University. Some involve ballot initiatives, others are trying to pass legislation. But taking redistricting out of the hands of partisans is difficult.

Only four states – Arizona, California, Idaho, and Washington – use an independent commission to draw congressional districts. In 37 states, the state legislature draws the boundaries, and in most, the governor must approve the map. Two states, Hawaii and New Jersey, use politician commissions. Seven states have just one member of the House, and thus there’s no congressional redistricting.

“I actually think that a movement toward nonpartisan commissions is in some ways the purest way to do [redistricting],” says Holder. “But I deal with reality, and between now and 2021, we're not going to get commissions in all of these states.”

Reaching for equity

Can foreign policy be feminist? Sweden says yes.

The term "business as usual" has been challenged across the working world. Why should foreign policy be any different? That's the question Sweden posed in pushing a shift in thought about the conduct of global diplomacy. (Read the full series here.)

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In October 2014, Sweden’s foreign minister made an unusual announcement. The country would put feminism at the center of its foreign affairs, she said – and not just in the name of fairness, or goodwill. “Failing to do so will ultimately undermine our overarching foreign policy and security objectives,” that minister, Margot Wallstrom, explained the following year. Sweden would let gender barge into every element of how it approached the world around it, from its time on the UN Security Council to how it doled out aid in the world’s poorest corners. Three years later, Sweden’s experiment has become a model: supporting everything from women’s job-training centers in Armenia to contraceptive access in Kenya. But saying you want your country’s foreign policy to be built on a vision of equality is one thing. Carrying that out in the coldly pragmatic world of geopolitics – that is entirely another. How much can a government really balance idealism and realpolitik, and who benefits?

Can foreign policy be feminist? Sweden says yes.

A doctor in a sparsely furnished Nairobi clinic, providing a young woman with birth control. A job-training center throwing open its doors to women in Armenia. A United Nations delegate urging the assembly to consider gender in its global climate change policy.

If those are the answers, then this is the question: What, exactly, does a feminist foreign policy look like?

It’s a question that has been floated many times since October 2014, when Sweden’s foreign minister, Margot Wallstrom, announced that her country planned to become the first in the world to put feminism at the heart of its foreign affairs.

“A feminist foreign policy aims to respond to one of the greatest challenges of this century, continued violations of women’s and girls’ human rights – in times of peace and in conflict,” Ms. Wallstrom explained at Helsinki University in March 2015. “Failing to do so will ultimately undermine our overarching foreign policy and security objectives.”

And so, she said, Sweden was going to let gender barge into every aspect of how it approached the world, from its role on the UN Security Council to how it doled out aid in the world’s poorest corners.

Over the last three years, other countries have begun to emulate Sweden’s feminist experiment; Canada, for instance, announced its own “feminist international assistance policy” last year. But it has also raised difficult questions about how far it is possible to balance idealism and realpolitik in the world of global diplomacy, and who benefits.

Saying you want your country’s foreign policy to be built on an idealistic vision of equality between the sexes is one thing. Actually carrying that out in the coldly pragmatic, and deeply male-dominated, world of geopolitics – that is entirely another.

And at the most basic level: What does “feminist,” as a guiding principle, even mean?

Ideals put to the test

For her part, Wallstrom has said a feminist foreign policy has to answer three questions. Are women’s rights being respected? Do they have enough resources to live safe and equitable lives? And are they represented in the halls and chambers where the world’s most important decisions are being made?

For her, those issues are deeply personal. More than three decades ago, she walked out on an abusive partner after he held a knife to her throat, a decision that she has said gave her the jolt of confidence to jumpstart a powerful political career. Within a few months, at age 25, she had been elected to Sweden’s parliament. She went on to head up three ministries and serve as UN special representative on sexual violence in conflict.

“She’s an incredibly popular politician and has been for a long time, which allows her to get away with saying and doing things that a lesser known or respected foreign minister never could,” says Emma Lundin, a historian who studies Swedish politics and social movements.

But even the most popular politician can’t rearrange the pieces of global diplomacy overnight. In 2015, Wallstrom accused Saudi Arabia – an important Swedish trading partner – of being a dictatorship with no respect for the rights of women; soon afterwards, the Swedish government cancelled a controversial military arms and training deal with the kingdom. The Saudis briefly recalled their ambassador to Stockholm and stopped issuing business visas to Swedes.

In the end, business leaders from the two countries came to a détente. But the incident was a reminder of how complicated it can be to carry out a foreign policy based on something as seemingly simple as equality.

Being the nice guy

The feminist agenda itself, though, can also serve Swedish self-interest, experts note, as a way for tiny Sweden – population 10 million – to stand out in a diplomatic world crowded with bigger, wealthier, and more powerful countries.

“All the way back to the cold war and earlier, Sweden has been cultivating a sense of its own difference on the international diplomatic scene,” says Dr. Lundin, the historian. The country has a long history of neutrality in global conflicts, she notes. “So policies like this feminist foreign policy, while laudable, are part of a long history of how to amplify the voice of Sweden in the world.”

Last January, for instance, when US President Donald Trump announced that he was cutting American family planning aid to any organization that performed or promoted abortions, Sweden was among those to quickly – and loudly – step into the gap.

Working for gender equality “will make America great again,” Wallstrom said, weeks before the US rule was imposed. “Without it, [Trump] will not be able to make America great again.”

Stockholm quickly pledged $22 million in additional aid for family planning, much of it to be distributed in sub-Saharan Africa, where the effects of the “global gag rule” were expected to be especially harsh.

One place that money ended up: a family-planning clinic in Nairobi’s busy Upper Hill neighborhood, where the two doctors on staff had recently begun buying supplies from DKT International, a family-planning nonprofit that sells low-cost contraceptives to private clinics. Although the group hopes to eventually become self-sustaining – they sell their products, rather than give them away – about half its operating costs in East Africa are currently funded by the Swedes, according to Collin Dick, the organization’s managing director in Kenya.

“The global gag rule is a scary thing for us,” he says. “But the Swedes have come in and shown us they are really passionate about wide access to contraceptives and safe abortion – it’s a big comfort.”

“To those who say that by being a feminist government we’re imposing our values on the world, I would make the counterargument that what the new US administration has done – that is imposing values,” says Gustav Fridolin, the Swedish Minister of Education, who has been involved in a Swedish-supported effort to expand sex education in schools across Africa. “We cooperate with countries with very different ideals and laws than us.”

On-the-ground asterisks

At times, however, it seems to critics of Sweden’s foreign affairs stance that the country actually has not one, but two policies marching side-by-side and sometimes out of step. Gender equality may sound like a simple ideal, but it’s also a very broad one – and the real-world complications of implementing it are rife.

Sweden has said it is dedicated to “strengthening the human rights of women and girls who are refugees or migrants,” for instance – even as its door swings shut on many of those migrants.

Six thousand miles away, in Colombia, Sweden has pushed to ensure that more women are included in a historic peace process between rebels and the government after five decades of conflict; it also signed a deal paving the way for major imports of Swedish arms.

Stockholm has promised about 95 million euros ($120 million) between 2016 and 2020 to support the fragile peace process, and contribute to services and economic development in the most-affected corners of the country. Much of that money is earmarked to increase women’s participation.

“The [Colombian] government is paying more attention to women’s rights and gender perspectives” as a result of pressure from countries like Sweden, says the director of a Colombian NGO that focuses on women and peacebuilding, who asked not to be identified over concerns that it could affect future funding from Sweden. The Swedes “are an important ally when it comes to lobbying and advocacy” for women, she says.

But Sweden has parallel, and different, interests. In March 2017, Sweden’s enterprise minister signed a cooperation agreement with Colombia allowing Swedish companies to export fighter jets to Colombia.

The Swedish government framed the agreement as a way to help Colombia’s armed forces adapt to their new peacetime role. But critics pointed out that the country’s military had recently been implicated in wartime atrocities, and questioned whether enough had been done to ensure the human rights of civilians – particularly women – would be protected as the military bulked up.

“At the end of the day, the geopolitical realities have a tendency to guide the government on how to act,” says Helene Lackenbauer, a researcher with the Swedish Defense Research Agency. “There is a feminist agenda that is absolutely there, but it is also sometimes toned down as needed.”

Contributing to this report were Whitney Eulich in Mexico City, Sara Miller Llana in Paris, and Paula Rogo in Nairobi.

After decades of violence, Colombia's rebels make pitch to voters

The path from bullets to the ballot box is fraught at best. History shows it can be done, though, if former militants commit long-term to confidence-building measures that prove a fundamental change of heart.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Manuel Rueda Contributor

For more than 50 years, FARC was best known for its fight to overthrow the Colombian government and replace it with a socialist revolution. But since the 2016 peace accord, the former guerrilla fighters have been focusing their efforts on making change through formal political channels. The peace deal guarantees them 10 congressional seats, and a former rebel leader is running for president. But winning over voters – and in many ways rewriting the political landscape – is going to take time. Few expect FARC politicians to win more than their promised seats during this election. And they’re up against unique challenges, like ongoing threats to their safety by paramilitary groups. But there are important lessons to be learned from other demobilized rebels around the globe who have successfully transitioned into politics – from Northern Ireland to El Salvador to Nepal. “The FARC is a tough brand to sell,” says one campaign manager for FARC. “I think with time, people will notice [they] have coherent proposals and the ability to make a difference.”

After decades of violence, Colombia's rebels make pitch to voters

Valentina Beltrán spent the past 24 years working with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) as a guerrilla fighter, an educator, and a communications specialist.

Today, she’s running for office, one of dozens of FARC candidates for Colombia’s Congress. It's a controversial part of the peace process that has some hopeful for reconciliation with the rebel group, and others feeling betrayed by the government for granting them this opportunity.

On a recent Thursday Ms. Beltrán walked down a leafy pedestrian street downtown in Bogotá, the capital, handing out flyers emblazoned with the FARC’s logo.

“If you don’t vote, the same politicians will always win,” she tells a group of construction workers. Many pedestrians reject her flyers, frowning at her, or walking away as she approaches.

“It’s a tough job sometimes, but I think it’s also important to do,” says Beltrán. “We need to break with misconceptions, and help people realize that we are also made of flesh and bone.”

As Colombia emerges from 52 years of civil strife, the FARC are trying to carve out a new role for themselves. The guerrilla group fought for more than half a century to overthrow the government and spearhead a socialist revolution, a conflict that left an estimated 220,000 people, mostly civilians, dead. Now they are a legal political party, thanks to a 2016 peace deal with the Colombian government. And they will participate in this year’s congressional and presidential elections, fielding more than 70 candidates around the country.

Like the IRA in Northern Ireland, or the ANC in South Africa, the FARC are hoping that years of armed struggle will translate into significant influence on their country’s politics. But first they have to redefine their image and carve out their place in formal Colombian politics in order to win over a very skeptical public. Most voters here distrust them, and associate the group with reckless acts of violence.

Their entrée into politics will be an uphill battle, analysts say, with few expecting them to win more than their 10 seats guaranteed by the peace deal. But the experience of demobilized rebel groups around the world, and a general sense of discontent with established political parties, offers examples of potential future success, experts say. From Nepal to El Salvador, Paraguay to the Philippines, “surviving politically as a former rebel group is just a matter of time,” says Madhav Joshi, associate director of the Peace Accords Matrix project at the University of Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies.

“It’s not a quick fix,” he says of winning over the public. But rebel groups like the FARC have a surprisingly amount of leverage on their side, namely the social attention and programs they fought for in the peace accord.

A 'tough brand to sell'

Unlike rebel groups in Ireland or Central America, the FARC are entering politics with minimal support.

While the guerrillas were popular in some remote pockets of the countryside, where they waged most of their struggle, urban Colombians have mostly seen them as a threat. The group was known for conducting lethal car bombs, kidnappings, and other human rights abuses, like the forced recruitment of children.

FARC leader Rodrigo Londoño, who launched his presidential campaign in January, is currently one of the most disliked public figures in Colombia. His support in electoral polls hovers around 2 percent, making him a fringe candidate, with practically no chance of winning the May 27 presidential vote.

A recent spate of bombings in the north by a smaller guerrilla group, the National Liberation Army (ELN), isn’t helping either. Many voters are already disappointed with the peace deal and the fact that FARC rebels are campaigning for office instead of languishing behind bars. These bombings open old wounds – with the help of politicians who have claimed falsely that the ELN is acting as the FARC’s “armed “ branch.

“The FARC is a tough brand to sell,” says Elkin Jair Limón Lerma, a former city government official in the oil town of Barrancabermeja. He is now working as a regional campaign manager for the former rebels.

“I think with time, people will notice the FARC have coherent proposals and the ability to make a difference,” Mr. Limón says.

In his home state of Santander, the FARC have campaigned among union groups, environmentalists, and farmers who are seeking greater access to land. The FARC have discussed plans to protect local water sources from gold-mining ventures, promised to stop the privatization of a state-run fertilizer plant, and have talked about improving the local oil refinery.

Limón says that joining the FARC’s new party has given him a chance to advocate for policies he believes in. And he’s not the only civilian joining them. In Bogotá, the FARC’s list of congressional candidates includes a rapper, a transgender activist, and an electrical engineer who wants employees to be compensated for the time they spend getting to work.

“They have been open and listened to our proposals,” says Andrés Camacho, one of the FARC’s civilian candidates in Bogotá. Mr. Camacho is running in a national election for the first time in his life.

A toned-down message

The peace deal signed with the government ensures the FARC 10 seats in Congress for the next eight years, regardless of how many votes they get. But after that time is up the FARC will have to gain a minimum number of votes to stay on the ballot, like any other party in the country.

That means it’s essential for the former rebels to improve their image if they want to survive at the ballot box, says Luis Carlos Pacheco, a political consultant here.

“They have to tell the truth about everything that happened,” Mr. Pacheco says.

The guerrillas already seem to be toning down their once-radical discourse in an attempt to get closer to the average Colombian voter.

As their campaigns begin, they have ditched talk of Marxism, revolution, and socialism, for more moderate promises of decreasing income inequality and improving social services. And they have a natural platform in the peace accord they helped design.

“That’s key,” says Professor Joshi, from Notre Dame. “In their election manifest, they can talk about, ‘We negotiated these [socioeconomic issues with the government] and we are the champions for your cause.’ ”

The former rebels’ logo, which bore two rifles, has been replaced with a red rose, the same symbol used by center-left parties in Europe.

Even the group’s name has changed, from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia to the Common Alternative Revolutionary Force. The FARC acronym has been kept, though, in an attempt to keep party militants unified.

“A few years down the line, changing the acronym may not be the worst idea,” says Kyle Johnson, an analyst at the International Crisis Group. “At a subconscious, emotional level, people link FARC to violence.”

Mr. Johnson believes that in the upcoming election the FARC will not be able to get more than the 10 seats allotted to them. It is just too soon after the war, he says, and the guerrillas lack a solid “ground game.”

But a successful transition into politics is not just in the FARC’s hands. In the past, smaller guerrilla groups have made peace with the Colombian government, only to see their leaders assassinated by right-wing extremists, and their parties diminished as a result.

The Patriotic Union, a socialist party that rose out of a previous round of talks between the government and the FARC, had 3,500 militants killed in the 1980s and ‘90s. The group barely manages to win seats in city councils nowadays.

The Colombian government will have to ensure tough action against paramilitary groups still roaming the countryside in order for this not to happen again, says Robert Karl, an assistant professor of history at Princeton University, who focuses on modern Colombia. “The biggest question mark at this moment is the FARC’s [own] security.”

There’s also the need for cooperation and coalition-building with existing parties, Joshi says. “The chance for a political future hinges on working with” an established party, whether it’s left, right, or center. And, down the line, discontent with established political parties – currently a global trend – could mean a leg up for demobilized rebel groups, which was the case with Maoists in Nepal.

“It’s not only about the social message, but also about the other parties that aren’t delivering” on their promises to the voters, Joshi says.

But, so far no other party running in the election have sought an alliance with the FARC, fearing the association could lose them votes, analysts say.

In the meantime, the FARC’s campaigners will continue to walk the streets like Beltrán, the candidate handing out leaflets downtown, trying to get the attention of skeptical voters.

“The media have depicted us as the enemy” says Beltrán. “We want to break that paradigm and show people here that we are regular folks who also dream of a better future.”

Whitney Eulich contributed reporting from Mexico City.

In California's solar boom, a substory of economic disparity

Power to the people? Green energy is often seen as revolutionary. But it won't broadly reshape how we light our homes and stay connected unless it reaches across the economic spectrum.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

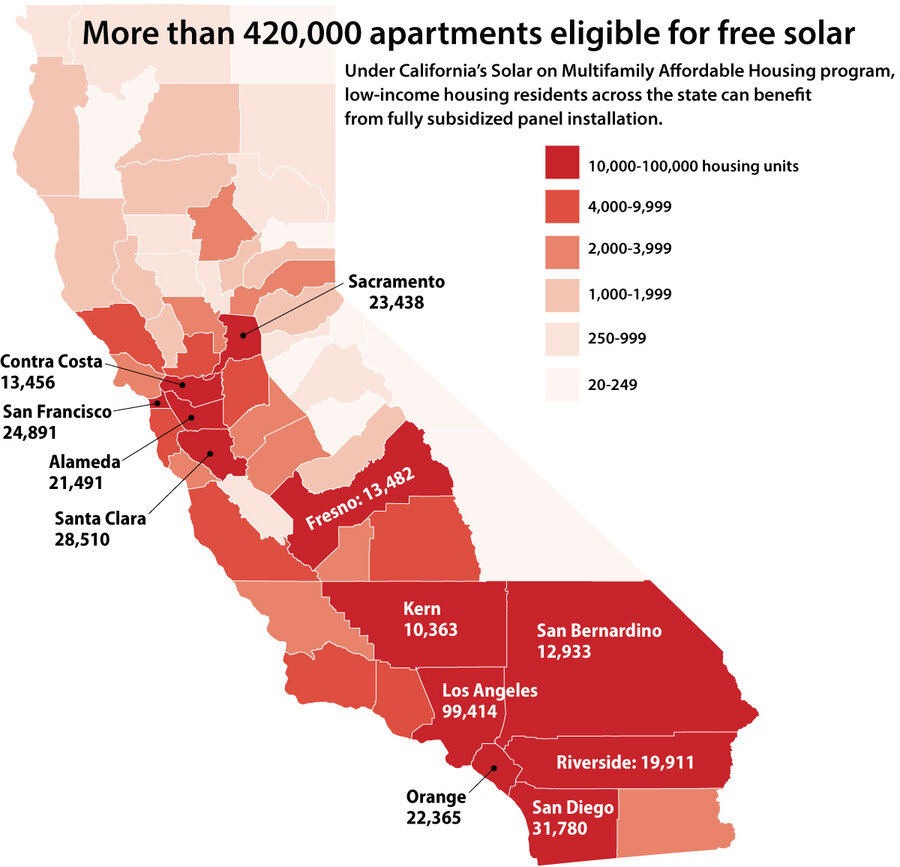

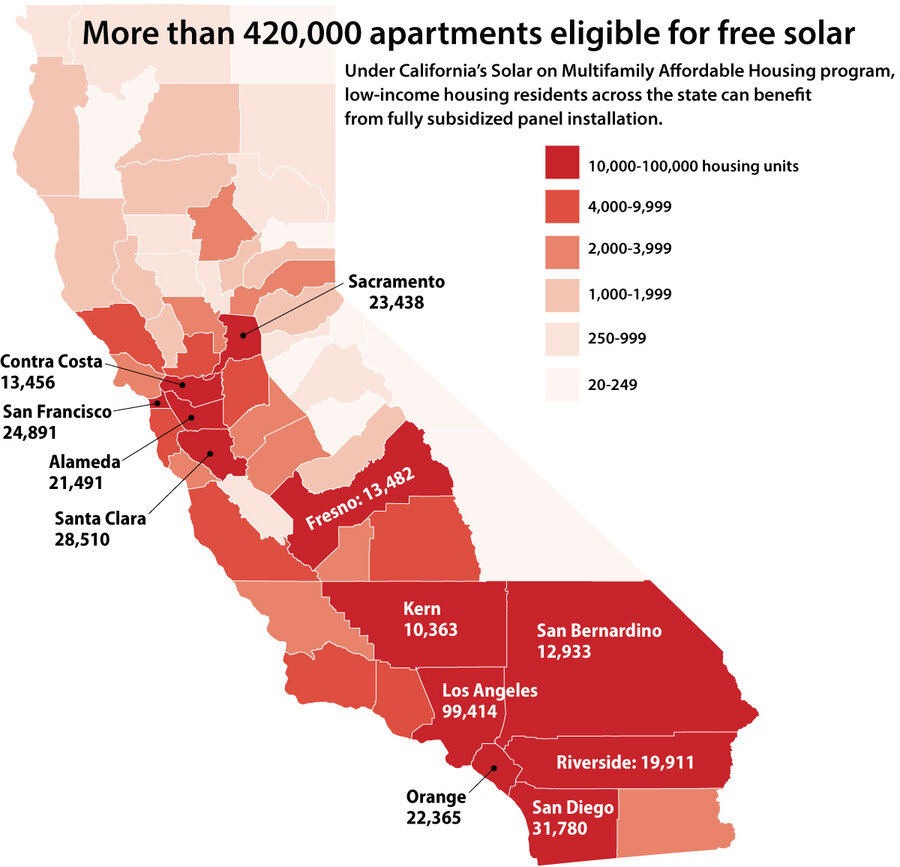

By and large solar panels, and the savings they bring, have been a luxury for only wealthy homeowners. That idea doesn’t sit well with California state Assemblywoman Susan Eggman. “If we are going to experience a revolution in how we think about energy, it should be for everyone, not just elites,” she says. That’s why she helped create a program to fully subsidize solar panels on apartment buildings in disadvantaged areas of her state. The Solar on Multifamily Affordable Housing program aims to bring electricity savings to low-income residents while contributing to the state’s ambitious greenhouse gas reduction plan. California has committed to reducing such emissions to 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030. “California has been a leader in setting ambitious energy goals,” says Gladys Limón, executive director of the California Environmental Justice Alliance, “but we need to make sure that all communities have access ... or else we will fail.”

In California's solar boom, a substory of economic disparity

The Golden State may produce more solar energy than anywhere else in the country, but when it comes to being green, there are “two Californias,” says Assemblywoman Susan Eggman.

The mountainous “spine” of central California, as Ms. Eggman likes to call it, is very different from the coast: there are more low-income households, higher electricity bills, and more expensive estimates for solar panel installation.

To bring California’s green reputation to places like her hometown of Stockton, Calif., Eggman created the Solar on Multifamily Affordable Housing (SOMAH) program. Under Assembly Bill 693, the program fully subsidizes solar panels on multifamily buildings that are located in disadvantaged areas, have a number of federally subsidized units, or where the majority of tenants earn less than 60 percent of the area’s average income.

“If we are going to experience a revolution in how we think about energy, it should be for everyone, not just elites,” says Eggman. “If you give people a chance, and offer them an opportunity to be a part of this, they will do it.... We just haven't done a good enough job of extending the opportunity.”

Until now, solar panels – and the savings they bring – have largely been a luxury for only wealthy, single-family homeowners. Unless low-income Californians own their own home, they don’t have the autonomy over their building to install solar panels, even if they could afford the $6,000 to $27,000 installation costs. After these upfront costs, solar paneled-homeowners can get credits on their electricity bill through California’s net metering program, and even get paid for excess solar energy they produce.

“The way energy metering is set up, it is very lucrative for people with solar systems and they are being funded by everyone else who doesn’t have solar. It’s inequitable and it’s a concern,” says Elise Torres, staff attorney at TURN, The Utility Reform Network, an advocacy group that works to protect low-income homeowners from high electricity bills. “[SOMAH] is something we could get behind and support.”

By 2030, California aims to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions to 40 percent below 1990 levels, a plan that includes deriving at least 50 percent of its electricity needs from renewable energy.

SOMAH presents an opportunity to meet ambitious statewide goals, says Gladys Limón, executive director of the California Environmental Justice Alliance, a nonprofit that cosponsored SOMAH. A 2012 report from the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) found that only 6 percent of residential solar was installed in disadvantaged communities, while these same communities likely make up 25 percent of the state.

“California has been a leader in setting ambitious energy goals, but we need to make sure that all communities have access ... or else we will fail,” says Ms. Limón. “There is a greater understanding [in the state legislature] of the need to make sure disadvantaged communities aren’t left behind in the clean energy economy, but there is still a lot of work to do.”

'We pick paying the bills'

The director of Esperanza Community Housing, Nancy Halpern Ibrahim, and her neighbors, many of whom are Latino, say that their local environment is too often treated as if it were disposable.

“The environmental injustice is often crassly evident [in Los Angeles],” says Ms. Ibrahim.

For years, Esperanza Community Housing has been fighting to permanently close the nearby AllenCo Energy drilling site, which community members say has contributed to various health problems. Ibrahim keeps a mason jar of oil from the AllenCo site on a bookshelf in her office to remind herself of her community’s battles.

Esperanza’s Budlong Apartments – a 12-unit apartment building located less than two miles from the AllenCo drilling site – is one of the nearly 800 buildings in Los Angeles that qualify for SOMAH benefits. And while the program does not solve all issues of environmental injustice in Los Angeles, it is a step in the right direction, says Ibrahim.

“Anything that democratizes a green benefit by prioritizing communities who can least afford it,” says Ibrahim, motioning around her, “I support.”

CPUC has tried to bring solar panels to these communities before. The Single-Family Affordable Solar Housing Program (SASH) and the Multifamily Affordable Solar Housing Program (MASH) were launched in 2009 as the country’s first statewide low-income solar programs, offering rebates and incentives for installation.

But even for affordable housing developers, who often have more money on hand and may value an environmental reputation, installation is still too expensive with these programs.

The Community Corporation of Santa Monica (CCSM) rents to almost 4,000 low-income Californians, and about 500 of them are children, says executive director Tara Barauskas. Thus far, MASH has been the best financial deal Ms. Barauskas can find for her buildings. They have used the program to install panels on some of their complexes but it’s not always affordable – even though commitment to energy efficiency is an important component of CCSM’s mission.

“On some buildings, if we had to fix other things, we couldn’t do the solar panels,” says Barauskas. “They weren't necessary for survival.... If it's between paying the bills or solar panels, we pick paying the bills.”

Reimagining solar incentives

Although SOMAH passed the state legislature in the fall of 2015, it wasn’t until January that CPUC agreed upon the final structure of the program. CPUC plans to hire a full-time administrator by the fall, and begin signing up housing developments for installations soon after.

Despite some overlapping features with previous incentive programs, the latest SOMAH initiative is different. Not only are the panels fully subsidized, but the program also has another key aspect that differentiates it from its predecessors: 51 percent of the energy bill savings must go to the tenant, not the landlord or building owner.

“This is not a continuation of MASH, but a reimagining of the next 12 years of programming.... It goes beyond being an incentive program,” says Stan Greschner, vice president of government relations at GRID Alternatives, the nonprofit selected by the public utility to administer SASH. “It really has the potential to be the most innovative and comprehensive multi-family clean energy programs in the country.”

California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC)

SOMAH plans to be a bigger, both in terms of the number of Californians served and the amount of solar energy produced. Within the next 10 years, SOMAH plans to install 300 megawatts of solar panels. By comparison, the state’s MASH program has installed almost 34 megawatts of energy since 2008.

At least 3,500 buildings across the state currently qualify for panel installation under SOMAH, says CPUC solar analyst Tory Francisco, and in these buildings there are almost 255,000 individual rent-assisted units.

Of course, a program of this scale is not cheap. The initiative will likely cost $100 million annually, funded by the state’s greenhouse gas cap-and-trade program. When it was going through the state legislature, 35 percent of both the state Assembly and Senate opposed SOMAH. Eggman attributes the majority of this opposition to discomfort with the program’s funding source.

“If you are against cap and trade, then you need to be consistent and vote against everything that’s a part of it,” says Eggman.

But apart from some politicians, it is difficult to find an industry or activist group that opposes this legislation.

Solar companies are especially excited about SOMAH, says Kelly Knutsen, director of technology advancement at California Solar Energy Industries Association (CALSEA), because it opens up a new market with cost-efficient installation.

“It had support from the housing community, environmentalists, and not only did utility companies not oppose it, Southern California Edison actually supported it,” says Mr. Knutsen. “I’m not trying to be overly rosy about it, but it’s seen as a good use of public dollars.”

[Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct a misidentification of the utility that supported AB 693. It is Southern California Edison.]

California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC)

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Europe revives its power of attraction

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

For the past decade, internal crises over the eurozone, migrants, and wayward members have stalled the European Union’s outward reach. That changed Feb. 6 when the EU revived its welcome for six countries in the Balkans to join the bloc – some, ideally, by 2025. The southeast corner of Europe has twice been a powder keg for modern wars. To prevent another outbreak of violent ethnic nationalism, the EU wants the six aspirants for membership – Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia – to firmly commit to its “fundamental values” of liberal democracy. In return they can expect to win trade access, investment, and visa-free travel. The EU’s offer is designed to counter the rising regional influence of Russia, China, and Turkey as well as pervasive corruption (and some autocratic tendencies) in the Balkans’ young democracies. The six aspirants have much work to do on reform. Yet their eagerness to join shows how much the world has shifted toward believing it is better to be liked than feared. Despite its woes, the EU still has a positive narrative that proves the power of attraction.

Europe revives its power of attraction

Many countries still compete for influence but these days they rely less on threats and more on the power of attraction, such as trade, cultural exports, or models of governance. A fine exemplar has been the European Union and its project to integrate the Continent. For the past decade, however, internal crises over the eurozone, migrants, and wayward EU members have stalled its outward reach. That changed Feb. 6 when the EU revived its welcome for six countries in the Balkans to join the bloc.

The southeast corner of Europe has twice been a powder keg for modern wars – in World War I and again in the post-communist 1990s. To prevent another outbreak of violent ethnic nationalism, the EU wants the six aspirants for membership – Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia – to firmly commit to its “fundamental values” of liberal democracy. In return they can expect to win trade access, investment, and visa-free travel.

The new EU strategy clearly states that the lure of potential membership serves as a “powerful tool to promote democracy, the rule of law and the respect for fundamental rights” in the Balkans. It calls on the six to make a “generational choice,” even at the level of how they teach their children.

The EU’s offer is designed to counter two troublesome trends. One is the rising influence of Russia, China, and Turkey in the region – all countries that lack the EU’s democratic credentials. The other is pervasive corruption and some autocratic tendencies in the Balkans’ young democracies.

The EU effort is being led by Bulgaria, whose proximity to the six compels it to seek a friendly neighborhood. But plenty of people within the Balkans still seek to join Europe. Among the post-communist countries of the former Yugoslavia as well as Albania, “EU membership remains the ultimate destination...,” writes expert Dimitar Bechev in a new book, “Rival Power: Russia in Southeast Europe.”

The EU hopes to have some of the Balkan nations join by 2025, an ambitious goal given the “fatigue” within the bloc over absorbing current members in Eastern and Central Europe.

And the six aspirants have much work to do yet in reforming their policies. Yet their eagerness to join shows how much the world has shifted toward a type of competition where it is better to be liked than feared. Despite its many woes, the EU still has a positive narrative that proves the power of attraction.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Everyone can win gold for integrity!

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

Thinking ahead to the Olympic Games in South Korea, today’s column looks at the power of being true to our inherent integrity as the sons and daughters of God.

Everyone can win gold for integrity!

It’s not just the Olympic Games’ governing bodies that are working to assure a clean Olympics, now the “athletes have taken part in grass-roots movements demanding that the Olympics stay true to their ethical values, especially fairness to fellow competitors” (“Olympic-class athletes find their voice of integrity,” CSMonitor.com, Dec. 6, 2017).

It’s so encouraging to hear how these athletes are pledging to present a drug-free event. And it’s likely that a strong ethical stand for fair play means the Games will attract greater support and a wider audience.

Yet, strong ethics and consistent honesty in the Olympics have a much greater impact than just the effects they may have on crowd sizes and revenues. That’s because in such significantly substantial ways, honesty and integrity, wherever expressed, bless people’s lives. Pure honesty expresses a deep respect for one’s neighbor. In sports, this includes respect for one’s fellow competitors. Honesty is an expression of love and it contributes to the kind of competition that gives all participants fair opportunities to contend.

But honesty is also good for the individual expressing it. For some time a friend of mine, a professional athlete, used steroids. The day came, though, when he turned away from them completely and never looked back. His career is even more successful now and, for many years, he has devoted his time to helping other athletes. His happiness is truly off the charts.

The turnaround in my friend’s experience makes sense to me because I understand honesty to be more than just the right thing to do as a good person. It is actually a quality that expresses our spiritual nature as sons and daughters of the Divine. In her key book on healing through a spiritual understanding of God, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy explains, “Honesty is spiritual power” (p. 453). More than just goodwill, then, the spiritual power of honesty is evidence of the presence and influence of God, or good. The expression of genuine honesty brings spiritual light – spiritual good – to the world, strengthening it through God’s active goodness.

On the other hand, the perceived rewards of dishonesty are ultimately a big disappointment. In the long run, nothing beneficial results from selfishness and immorality. When people adulterate their ethics and integrity, they’re making the mistake of believing that good can be found in that which is not good, that which is not pure and therefore not of God.

In his Sermon on the Mount, Christ Jesus said, “Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God” (Matthew 5:8). A heart that is pure is honorable, loving, and honest. But is goodness something that some possess and others do not? While it seems that way, Jesus’ healing ministry evidenced the opposite, proving so clearly that goodness, purity, and honesty are natural to man as God’s spiritual expression, and that the dishonest or immoral individual can be reformed through understanding this true nature. In such cases, the spiritual power of honesty, having its source in God, good, can be felt immediately by anyone who turns away from deceit and toward the light and strength of divine goodness – just as light shines immediately on the face of someone who turns toward the sun.

At their best, the Summer Games and Winter Games can be a showcase of good morals and ethics, but that clearly hasn’t always been the case. We can help the athletes value honesty and discover the spiritual power that goes with it, through prayer that acknowledges that all the participants are children of God, and therefore are created to express man’s true purity.

While an Olympic medal can mean so much to athletes who have trained for many years, living a life of integrity is a rewarding victory in itself, and one that all competitors have it in them to win.

A message of love

Taiwan temblor

A look ahead

Thanks for spending time with us today. Tomorrow, join us as we look at why South Africa’s ANC would want to oust President Zuma. He may have hit a point of no return with voters wearied by a decade of corruption charges and economic mismanagement.